“The Lumber-Room” by H.H. Monro (Saki) is one of the short stories from Beasts and Super-Beasts, published 1914, though it was first published in a newspaper. He died two years later in the war. Significantly for this short story, Saki was gay.

There’s something very Peter Rabbit about this short story for adults. Peter Rabbit was widely read to children at the time Saki’s story was published. It’s conceivable that the fictional adults in “The Lumber-Room” believed all children (as proxy rabbits) want to get up to mischief in gardens because they had read Beatrix Potter’s tale over and over.

SETTING OF “THE LUMBER-ROOM”

- Saki’s stories are set in upper-class Edwardian England.

- A lumber-room is a room in an upper-class English house where items are stored when not in use.

- Jagborough is a fictional seaside resort but has a likely-sounding English name.

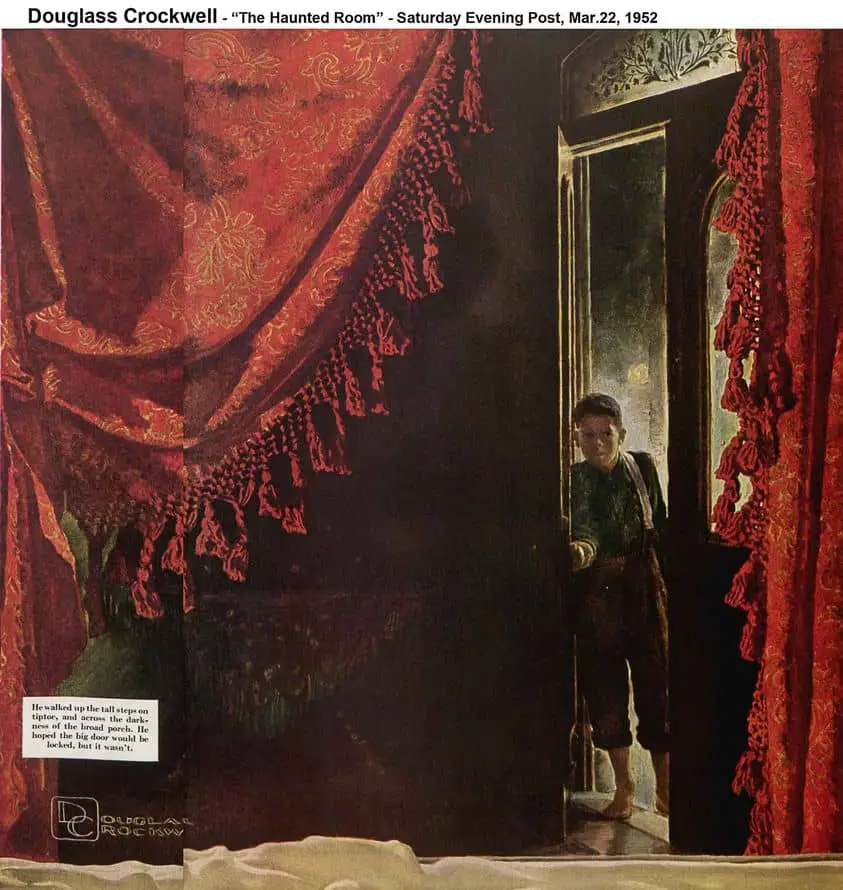

- Nicholas wants to go into the deepest, most secret part of the house (rather than outside in the garden) to see what’s there. This is his inner-world, his imagination, his subconscious.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE LUMBER-ROOM”

“The Lumber-Room” is a carnivalesque story, or certainly would be if it were written for children. A child goes on an adventure, has fun without adult supervision, then returns to the safe but restrictive adult world by the end of the story. Except in this one, there’s no return to safety. The child main character of Saki’s short story understands that adults can’t be trusted. This is not a message you typically (or ever) see in picture books for children, unless it refers specifically to ‘adults can’t see the same magic’.

Notice that the aunt manufactures a ‘carnivalesque’ adventure (‘something of a festival nature’) for the other children, but this is unlikely to be fun in the slightest. We can deduce this because the girl-cousin hurts herself getting into the car and cries loudly. When supervised and arranged by adults, especially in the spirit of punishment for the ostracised, carnivalesque adventures are nothing of the sort. Sure enough, we learn the other children had a terrible time. The boy’s boots were too tight (his conservative, mainstream life too constrictive), and the tide had been up, leaving no space for play.

Saki opens “The Lumber-Room” in an interesting way, by telling us a self-contained story in the first paragraph. This mini story describes why Nicholas is in disgrace. Hitchcock might have called the frog in the bread-and-milk a McGuffin — we never hear about the frog again, but it kicks the real story off. This initial micro-story lets Nicholas have his Anagnorisis upfront. The story now progresses with a wiser, more knowing, less trusting child, because Nicholas has learned that adults can turn a blind eye to what’s right in front of them, insisting things are one way when they decidedly are not.

SHORTCOMING

Nicholas is your classic trickster — very intelligent but believably so. Readers love tricksters. We identify with tricksters immediately.

Nicholas’s Shortcoming is that he is a child. This is true for almost all children in stories, because their freedom is severely limited.

Not only that, Nicholas is a misunderstood child. We know from this particular episode of his life story that he wants to look at a narrative tapestry while the adult assumes he wants to get into the gooseberries, but this must only scratch the surface of all the ways in which he is misunderstood.

Nicholas is an aesthete rather than an athlete — the two main types of man as decided in the 19th century. He likes to walk around and look at nice things, inhaling their scent, considering the stories behind them.

Nicholas might therefore be considered a proxy for a gay adult man living in the Edwardian era. This man is expected to like ‘gooseberries’ but is in fact drawn into the hidden, secret pleasures of the locked room, which contains many beautiful treasures.

DESIRE

Nicholas wants to get into the forbidden lumber-room and explore all the wonderful things hidden to him.

The off-the-page gay man can’t necessarily explain why he loves the forbidden treasures so much, but he does love it and takes every opportunity to go there. When he does go there, he hurts no one. And the things that are in there are off-limits for no good reason.

The aunt-by-assertion was one of those people who think that things spoil by use and consign them to dust and damp by way of preserving them.

This is not a story of someone who is acting in the world, where there is danger, but someone who is content to watch on, which is bearable so long as he understands his own inner self.

OPPONENT

The ‘aunt’ is his main opponent, though she is simply standing in for ‘correct and upright society’ more generally.

Saki himself ‘was brought up by two unmarried aunts with a fondness for the birch, and developed a lifelong aversion to spinsters’ (The Guardian).

PLAN

Nicholas understands the concepts of reverse psychology and diversion.

- He will reinforce the aunts beliefs about him by making a show of crawling into the gooseberry garden.

- While the aunt is busy hunting him down in the overgrown garden he will use the key to get into the lumber-room.

BIG STRUGGLE

There’s something very fairytale about the Battle scene, in which Nicholas knows full well the ‘aunt’ stuck in the tank is exactly who she says she is, but he makes us of superstition and folklore to pretend naïveté, cracking on that he really believes she’s a changeling of some sort.

ANAGNORISIS

As mentioned above, this story structure is a bit unusual because the mini-story upfront gives Nicholas his revelation.

The big reveal for the reader is that Nicholas is not interested in gooseberries, but in the more adult, less understandable pleasures of the treasures in the lumber-room.

Nicholas didn’t know what he’d find inside this forbidden room, but once he entered it, the pleasures were more than he could have imagined, especially when he found the book of beautiful birds.

Before that he observes a tapestry meant as a fire screen. Saki describes it for the reader. When writers describe a painting or photo within a story this is known as ekphrasis, which was a popular Greek pastime. Short story writers make use of it even now, and the tapestry in “The Lumber-Room” seems to function as an indirect way of arriving at a character’s Anagnorisis.

What does Nicholas understand by looking at the hunters and the stag?

A man, dressed in the hunting costume of some remote period, had just transfixed a stag with an arrow; it could not have been a difficult shot because the stag was only one or two paces away from him; in the thickly-growing vegetation that the picture suggested it would not have been difficult to creep up to a feeding stag, and the two spotted dogs that were springing forward to join in the chase had evidently been trained to keep to heel till the arrow was discharged. That part of the picture was simple, if interesting, but did the huntsman see, what Nicholas saw, that four galloping wolves were coming in his direction through the wood? There might be more than four of them hidden behind the trees, and in any case would the man and his dogs be able to cope with the four wolves if they made an attack? The man had only two arrows left in his quiver, and he might miss with one or both of them; all one knew about his skill in shooting was that he could hit a large stag at a ridiculously short range. Nicholas sat for many golden minutes revolving the possibilities of the scene; he was inclined to think that there were more than four wolves and that the man and his dogs were in a tight corner.

There are plenty of interpretations, but here’s mine:

- ‘It would not have been difficult to creep up to a feeding stag’ and it would not be difficult for heteronormative society to work out what’s going on right under their noses if only they were to look.

- But when they do look, it is very dangerous for the stag.

- It is pleasurable in this forbidden room but it is also dangerous. Perhaps danger is part of the pleasure itself.

- There’s no easy way to win the big struggle when you are the stag.

Nicholas’s secret is now a safe thing. He comes up with a way the story on the tapestry could end that could be all right. Will Eaves, on the Neuromantics podcast says this crops up a lot in Greek myth: How can these sexually irresponsible labile figures have an effect in the world that ends up restoring balance? (Myth is very important to Saki’s literary world. A lot of the macabre stories have roots in green man figures and whatnot.)

NEW SITUATION

The aunt who is — significantly — not Nicholas’s own aunt doesn’t really know him. So she is obliged to believe that perhaps he was naive enough to think that she had been swapped out by some evil witch. We don’t get to know of any further consequences for Nicholas but we can extrapolate that the aunt has either got the measure of him now (that he is much smarter than he cracks on) or else much dumber. I bet she’s keeping a close eye on him, to work out which of those it is.

The gay man sort of gets away with entering the metaphorical lumber-room because people simply assume he wants something else entirely. While they are assuming that, they aren’t looking for him in there. But he doesn’t get away with it entirely. Others know something is up. They know that he is tricking them in some way, though can’t quite get the measure of him, in a society where sexuality and orientation isn’t discussed. People don’t even have the language to discuss it. In that way, the adult gay man is similar to a child — children know things, but are often ill-equipped with language to describe these things.

MORE

Credit goes to Episode 3 of the Neuromantics podcast for alerting me to the gay subtext of this story. I’d otherwise have missed it. (At 29 minutes) The Neuromantics talk about “The Lumber-Room” in a discussion about people’s inner-world. Nicholas’s inner world is so much more important and satisfying to him than anything else.

Header painting: John Dawson Watson — The Collector’s Home