“The Little Photographer” (1952) is a short crime story by British author Daphne du Maurier. Find it in The Birds and Other Stories, previously published as The Apple Tree collection. Like Rebecca, people of rank are shown to be capable of terrible things. This is no shock to a modern audience, but was more shocking to the contemporary readership of du Maurier, when concepts of ‘good blood’ and ‘bad blood’ kept the ruling elite in power.

In other ways, this story is timeless. This one contains revenge p*rn, before it was known by that term.

CHARACTERS

English: marquess (m) and machioness/marquise (f).

French: Marquis (m) and marquise (f).

This title is hereditary and high-ranking.

A marquess is “a member of the British peerage ranking below a duke and above an earl.” It’s less well-known as a title than duke or earl (or viscount or baron), possibly because there are fewer marquessates than dukedoms or earldoms in Britain.

Merriam Webster

French nobility ranks: Prince, Duc, Marquis, Comte (historical), Vicomte, Vidame (feudal, rare), Baron, Chevalier.

THE MARQUISE

Du Maurier doesn’t offer us her name. She is known only as The Marquise. This is her position and entire identity in life. As much as she craves the admiration which comes from high rank, at times she longs to escape it.

Until The Marquis turned up, she was supposed to marry her surgeon father’s assistant. But she is beautiful, so she has been allowed the opportunity to marry into wealth and rank. In summer they live at their chateau in the country. She spends winters at their Paris house, again entertaining Édouard’s family, who stay for lengthy periods. This new life has its advantages, but wealth has isolated her from the girlfriends of her youth. She feels prematurely middle-aged. Everything exhausts her, except for the odd occasion when her husband brings one of his friends to meet her, and she sees herself as desirable again via a man’s appreciation. She is not one bit sexually attracted to these men; she is excited by their attraction to her.

MONSIEUR LE MARQUIS

Édouard the Marquis cannot join his wife and children on summer holiday in Lyon after all, due to ‘business’. The Marquis was in his forties when he finally picked a beautiful young woman to bear his children.

MISS CLAY

The Governess for Céleste and Hélène.

MADEMOISELLE PAUL

A crippled woman from a poor family who has one of the little shops in the seaside village, running the business alongside her brother.

MONSIEUR PAUL (THE LITTLE PHOTOGRAPHER)

The brother does not consider himself a shop boy. In time it becomes clear: He always had plans to escape his lowly rank. He has had a taste of a more glamorous life by honing his skill as a photographer. Now he sees a way into riches beyond his wildest dreams — if not the riches per se, the trappings of a luxurious life via connection to nobility.

At times he is described as a bird. He is small, he has a ‘nest’ in the grasses near the cliff. Ironically, he is not a bird at all. If he had wings, he’d have been able to save himself. He tried to launch — to fly into a higher class of society — but this little bird was hindered by his disability.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE LITTLE PHOTOGRAPHER”

SETTING

Lyon (also spelled Lyons) is the capital city in France’s Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, sitting at the junction of the Rhône and Saône rivers.

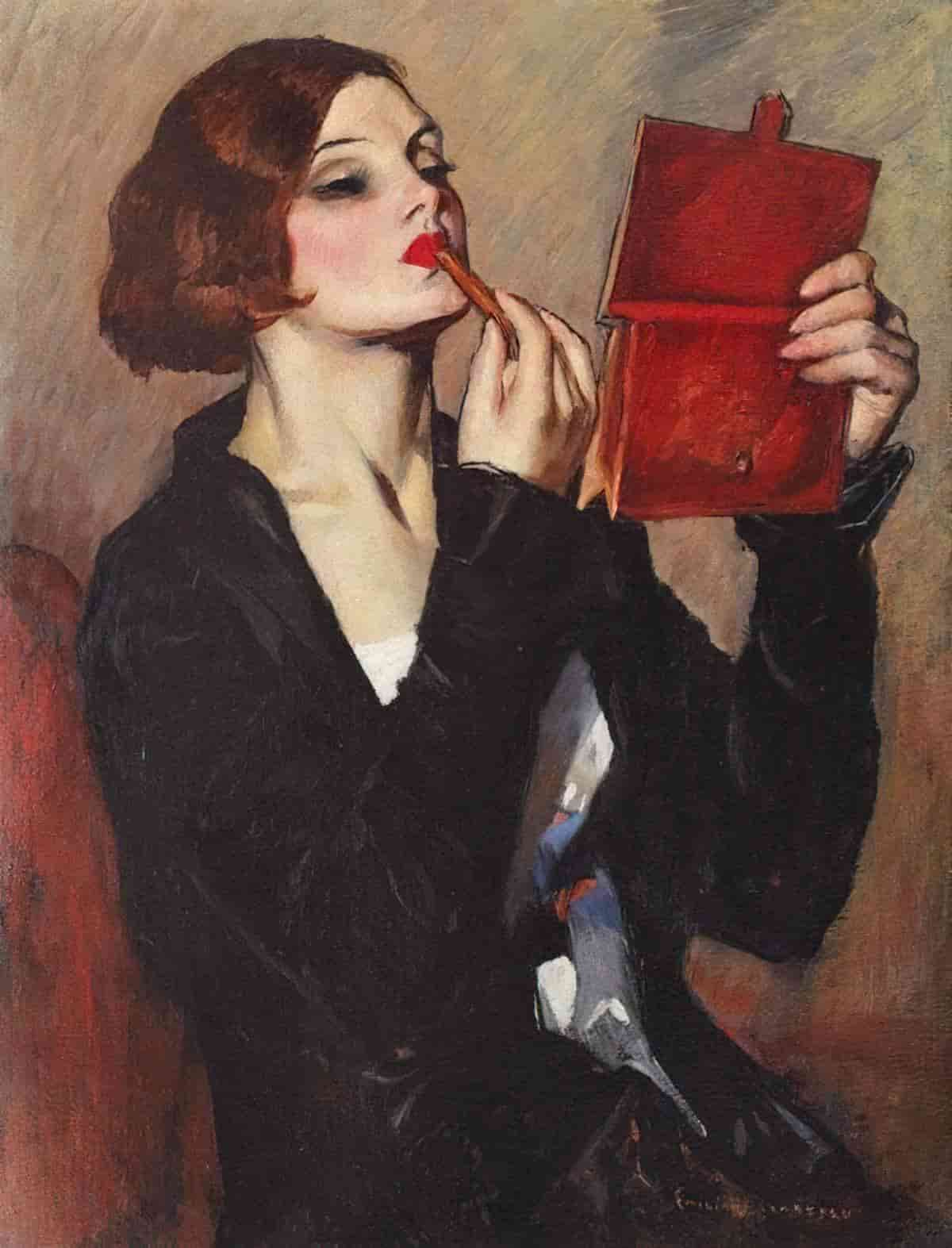

On a hotel balcony, under the Lyon sun, a woman languidly paints her fingernails, trying out three different shades of red and pink. Clearly a woman with more than one facet!

In the distance she hears children playing, her own two daughters among them. A governess tends to them.

A WEALTHY WOMAN IN A GILDED CAGE

In a letter, she has learnt that her husband won’t be joining them at the hotel. This is fine by her. She was warned before marrying him that she was getting herself ‘a very serious man’. The Marquise very much enjoys her life of castles and luxury, all without the constant bother of a husband.

FUN HAPPENS TO EVERYONE ELSE

She keeps in contact with her high school friend, Élise, who assumes The Marquise is leading an exciting and glamorous life, with much opportunity for erotic encounters. Élise, though married, is herself having an affair, despite being less beautiful and less wealthy than The Marquise.

Since learning that, The lonely, dead-inside Marquise imagines everyone around her is enjoying secret liaisons with each other.

MEET CUTE (IN A DARK ALLEY)

With all that backstory set up, now the story begins. The governess returns from the beach with the young daughters. Though the shops are closed for the hottest hours of the day, the Marquise decides to go for a walk. Now the vibe changes. She’s noticing the small creatures. Before, on the balcony, it was a bumble-bee, but now she notices the flies, how the sweat drips off her. She’s noticing squalor. She seeks refuge from the sun in an alleyway.

Suddenly she catches sight of a beautiful man’s face through the cellar window of a shop. (Symbolism much?) He knows who she is. Everyone around these parts knows who she is; when people of rank descend upon a town, the regular folk rally around. They speak of encounters for months, years.

ENTER: FRAMING SYMBOLISM

A few days earlier, The Marquise had entered the shop to get a roll of film developed. This man’s sister had served. The Marquise remembers now — a woman with terrible deformities of the legs and feet. Now she notices the man also has a club foot. It looks painful. Otherwise, he is beautiful, especially those arms in his singlet. He hadn’t expected to be serving anyone during siesta. But now his hands tremble and The Marquise very much enjoys the power she has over him.

Monsieur Paul is a photographer, an artist, whose sister normally runs the shop. He’s normally out on the cliffs taking shots of the seaside and ocean without tourists to crowd his panoramas.

How interesting. Du Maurier has shown us enough of The Marquise; we can predict what happens next. She hires him for a private photoshoot, where she very much enjoys being admired and closely observed by a beautiful man, especially one with a deformity. She enjoys the power imbalance. Du Maurier uses the word ‘subjection’.

A SUMMER FLING

The wealthy enjoy very long holidays. Over the coming weeks, feigning disinterest in Monsieur Paul, The Marquise decides to take her box brownie onto the headlands where she will just-so-happen to run into Monsieur Paul, also taking photos. She asks for photography tips. He obliges. She encourages him to take her photo. He obliges. Du Maurier leaves the rest off the page, but we can fill in the gaps.

The Marquise loves to be admired and, as a photographer, Monsieur Paul loves to do the admiring.

THE END OF SUMMER

Summer is drawing to a close. In five days’ time, The Marquis will arrive to pick up his wife and daughters. Unfortunately for The Marquise, he has fallen hopelessly in love with her, or into some lusty frenzy in which he imagines some sort of permanent sub-dom arrangement. He’ll travel with her, wherever she goes, be her lapdog, her footman. He is very discreet; no one will ever suspect.

The Marquise is horrified and terrified at once. What a ridiculous idea. Imagine a footman with a club foot. The entire point of male attendants is decoration and prestige.

POWER IS COMPLICATED

This suggestion was never going to work, because Monsieur Paul has broken the unspoken contract between them: The Marquise calls the shots, not him. Although The Marquise has far more conjugal wealth, Monsieur Paul is a man, and now he talks to The Marquise as a man talks to a woman, deciding her future for her. This power-inversion disgusts The Marquise. His deformed foot also now disgusts her, whereas before she regarded him with loving pity. Having no real power in the gilded cage of her dead, boring and lonely rich-lady life, The Little Photographer is only of use to The Marquise if she can dominate him completely. She only ever wants to be admired, because that is how her attraction works. She is attracted to the male gaze, not to men per se. Ergo, she can easily switch out one for another.

The guy flips out. For as long as photos have been around, men have been using naked images to shame, humiliate and threaten women. That’s what he does now. He threatens to tell her husband, everyone.

IMP OF THE PERVERSE

Imp of the Perverse: The sudden urge to push someone into the path of an oncoming train, or similar. (From an Edgar Allan Poe short story.)

In a panic, The Marquise pushes the small man off the side of the cliff. She can’t believe what she’s done.

Shaking and stunned, she makes herself go for the swim she said she was going to.

Someone finds the body. She feels lucky not to have touched the dead body as she swam in the sea, getting colder and colder but swimming on regardless.

Like the husband in “The Apple Tree“, who took only a week to get over his dead wife, five days later she’s successfully reset her mind. She’s looking forward to getting the hell out of this seaside town. Her husband would like to spend a weekend enjoying the seaside with his family, but The Marquise tells him it’s crowded, the room has been booked and they couldn’t possibly stay any longer than Thursday. (If you’ve seen the 2007 movie about Daphne du Maurier’s life, you’ll know she tried the same trick once.)

When he arrives, The Marquise gives her husband a surprisingly warm welcome. Notice how 20th century authors shifted narrative point of view without anyone editing them for ‘head hopping’? I feel the modern insistence on close, unwavering third person narration limiting at times. Without a brief spell in the husband’s head, we would not see The Marquise’s mask slip. Even to him, the lipstick she applies somehow makes her seem haggard, not more beautiful.

Of course, the grieving and financially precarious Mademoiselle Paul is onto her. She’s found the (presumably erotic) photos in the cellar, developed by her brother before his death. The woman’s eye gleams knowingly, even through her display of grief. To keep these photos secret, she’s after a permanent bribe.

A COMPLEX MORALITY

The Marquise is shocked to learn that Monsieur Paul took photos of her which she never knew he took. These days, taking sexually explicit photos of others without their consent, then sharing them, is a crime. Though it takes no time at all for new technologies to be utilised by criminals, it takes much longer for laws to catch up.

Monsieur Paul now seems worse, doesn’t he? But did he deserve what he got? He lost his literal life, but threatened to destroy someone else’s — for the economically precarious Marquise, a fate worse than death. The morality of this story just became a little more nuanced.

DOES THE MARQUISE GET AWAY WITH HER CRIME?

The police believed Monsieur Paul slipped and fell. He was disabled, after all. It was just a matter of time… wandering around up there with his camera…

Nope. The Marquise is pregnant. Her baby son will be born with a club foot and The Marquis will know exactly what his wife got up to on holiday.

Does it say this on the page? Also no. But what else could be the storytelling reason for the husband’s comment about his friend’s son, and the hereditary nature of paediatric club feet? (The heritability has been exaggerated by du Maurier for the story.)

The reader is left wondering: Does The Marquise have it in her to commit infanticide?

And what does it mean to have ‘good blood’? The Marquise was plucked from the middle class because of her good breeding potential, based on nothing more than surface beauty and glamour. Yet she’s not a good person.

Good blood doing very bad things. Criminal things. When du Maurier was writing, in the mid 20th century, it was important to critique such notions in popular fiction.

A MODERNIST SHORT STORY

As I read “The Little Photographer” I was very much reminded of Katherine Mansfield. Mansfield’s plots were typically understated, especially compared to this one. Mansfield wrote of wealthy people, but not of nobility. Mansfield (888 –1923) was a generation older than Du Maurier (1931–1989).

In the beginning of “The Little Photographer”, the characterisation of du Maurier’s Marquise could be pasted perfectly onto Mansfield’s characterisation of Linda Burnell — wealthy, bored, sexually dissatisfied wives with powerful but absent husbands, in depressive slumps by the seaside, their children cared for by other women.

Later, the scene where du Maurier’s Marquise visits the small shops reminds me of Laura in the “The Garden Party“, visiting the bereaved wife, affected by what she finds.

You’ll find bird imagery in “The Little Photographer”. Mansfield is also well-known for her bird imagery.

Mansfield was, famously, a pioneer in Modernism. Daphne du Maurier’s short stories come along near the end of Modernism. No one agrees exactly on when Modernism begins and ends, but the World Wars changed everything.

How is “The Little Photographer” Modernist?

- Du Maurier has written with ‘narrated monologue’, in which the reflecting mind is presented in the third person and in the preterite (a grammatical tense or verb form serving to denote events that took place or were completed in the past). We see the world as The Marquise sees her world, with a few brief exceptions. We don’t really now what Monsieur Paul thinks of her. Is he trembling because he admires her? That’s what she thinks but, for all we know, he’s trembling at the prospect of levelling up a socio-economic class. WE don’t actually know whether he is attracted to women. Is her husband really as absent and unobservant as she thinks? Perhaps he’s more canny than that.

- Before, the self had been understood in terms of a single transcendent ego, but Modernists put it to their readers that ‘self’ was not only multiple, but also mutable. The self is not one, single, never-changing thing. We change from moment to moment, as situations change. Du Maurier lets us know that her main character has multiple sides to her from the moment the nail varnish colours appear.

- A vitalist world view for artists meant they viewed character as both individuated and also as a part of a complex whole. By describing how The Marquise came to push a guy off a cliff, we understand how a person could be driven to that point. People do not exist in isolation. We’re all cogs.

- Pushing back against the Realists who came before, Modernist artists disputed the very notion of ‘real’. When The Marquise puts on sunglasses and the landscape changes colour, this symbolises a broader, Modernist world view. We see the world how we are, not how it really is.

- Overall, Modernist movements are about getting to some deeper truth. The light-penetration truth: A wealthy woman used her power to kill an innocent man with nowhere near the advantages. A deeper-penetration truth: Power is complex and comes in different forms. Humans will hang onto it at any cost. Losing power is a form of death.

- Du Maurier leaves gaps in the narrative. This allows readers to fill in the gaps for ourselves. (Perhaps you filled them in differently from me.)

- Because the reader is expected to do more work, the narrator of a Modernist story is more of an observer, acting more like a camera than a professor. In a story titled “The Little Photographer”, the ‘photography’ aspect works at every level. The Marquise likes to be observed, and we, the readers, grant her wish. Du Maurier as author has presented her entire life in a specific frame. If we were offered a different holiday, we’d interpret the character differently.

- Via the photographs seen by neither The Marquise nor the reader, readers construct part of the story. We can imagine for ourselves what they show and what havoc they can wreak. In Modernism, the reader reconstructs.

- Du Maurier has not passed judgement on The Marquise, instead, simply offering us the story, inviting us to draw our own conclusions. Modernists are not didactic. They want readers to think, but they don’t want to tell them the content of what to think.

- Modernists like to play with antithetic pairings (and other contrasts). We’ve got a rich-poor divide. We’ve got the abrupt change in emotional valence as The Marquise goes for a walk before stumbling into the alley and into trouble with Monsieur Paul. We’ve got a description of a vast ocean and cliff which juxtaposes against description of bees, blowflies and dragonflies. (The dragonfly motif is apparently a nod to Virginia Woolf’s ‘Kew Gardens’. It’s a metaphor of desire. Woolf is who we think of when we say ‘Modernism’.)

- Modernists use character tropes to de-historicise the individual. According to an historicist worldview, identity is stable and a result of continuity, social and cultural phenomena are determined by history. The son is who he is because of his father and so on. Modernists didn’t think like this. They broke the ties between generations. Du Maurier is breaking the mid-century mental shortcut of linking ‘good breeding’ to ‘good character’.

- Modernist main characters are allotropic (a word from chemistry meaning ‘exists in two or more different forms). The Marquise can be a compliant, loving wife. And when she is alone on holidays, she can also be someone else. The old-timey way of developing negatives fits nicely into this metaphor: Each photograph has a corresponding negative form. In this case, empathy, power and morality flips on a dime.

“THE LITTLE PHOTOGRAPHER” AS AN EXAMPLE OF THE INTERMEDIAL

The word ‘intermedial’ is similar to the word ‘intermediate’ but has only been around since the 1980s. Julia Kristeva introduced the term intermediality in 1986.

Intermediality: intertextuality into a media-related context.

Christine Reynier’s paper Beyond Cinema: Daphne du Maurier’s intermedial experiments in “The Little Photographer” argues that du Maurier should be known as more than a writer of women’s romance (since that is usually taken to be an inferior thing). Du Maurier straddled genres, packaging sophisticated literary techniques into work for readers of popular fiction, e.g. romance and crime.

By ‘intermedial’ Reynier explains what she means: ‘a literary work referring to another medium — here, photography’.

THE NARRATION WORKS AS A CANDID PHOTOGRAPHER

I see no good reason to impose gender on the narrator, especially a masculine gender, but Reynier explains here how reading “The Little Photographer” feels like flicking through stills:

The narrator makes his character come to life through her internal monologue and her silent observations of her surroundings, just as the photographer makes his subject come to life, not so much in the conventional posed photographs with her children — ‘a tableau, ready set’ — as in the photographs that he himself arranges, placing her hand or her chin to his own liking, or, more significantly, in the un-posed photographs he takes.

Beyond Cinema

Of course, those mystery-boxed naughty pics we never get to see were also taken candidly, but not in a good way. The Marquise did not give her permission. Candid gone bad.