If you’ve seen Jane Campion’s biopic about New Zealand’s most accomplished author, Janet Frame, you’ll already know that “The Lagoon and Other Stories” saved the author’s life. If she hadn’t won an award for this collection, she was in a psychiatric facility and in line for a leucotomy. After this book, Janet Frame lived a full and successful life as a writer.

The South Island of New Zealand is my childhood stomping ground. Janet Frame was born one year after my maternal grandmother and died four years after, so reading the stories of Janet Frame to immerse myself in the world of my grandmother — in fact all four of my grandparents, who all lived in Janet Frame’s era, with the same traditions, the same geography.

All the while, Janet Frame was observing it closely, writing it down. Let’s take a journey back to New Zealand, as it was in the first half of the 20th century — to a landscape which feels at once homely and defamiliarized to me.

JANET FRAME AND LORDE

New Zealand singer/songwriter Ella Yelich O’Connor (Lorde) is a keen reader and has named Janet Frame as a literary influence. She hasn’t named specific texts, but Lorde does mention the influence of short stories in general. Just for fun, I’ll consider how The Lagoon and Other Stories might connect to Lorde’s musical output so far.

The following statement from Lorde might apply equally to Frame’s The Lagoon and Other Stories:

I love writing a pop melody – there’s nothing better. For it to be simple but for it to be secretly complex and trick the brain … you can’t fake it; it’s a real experience.

That feeling of being able to talk to a lot of people and to make something that is kind of high-brow but also can be enjoyed in really simple ways.”

Lorde, Lorde says she doesn’t want to explain her lyrics anymore, NME

“THE LAGOON”

- Lagoon: a small freshwater lake near a larger lake or river.

- Supplejack: Ripogonum scandens, a common rainforest vine native to New Zealand. It can also grow in areas of swamp. Supplejack is a climbing liana, with hard but flexible stems. Edible. Tastes like spinach. Also has edible berries.

- kidney fern: Hymenophyllum nephrophyllum is a filmy fern species native to New Zealand. It commonly grows on the forest floor of open native bush. Individual kidney-shaped fronds stand about 5–10 cm tall. They shrivel up when the weather is hot to conserve moisture, then re-open in the rain.

- tiddlers: a word for a small fish

- pop-pop boats: A pop-pop boat is a toy with a very simple steam engine without moving parts, typically powered by a candle or vegetable oil burner. The name comes from the noise made by some versions of the boats. The toy boat contrasting with the steam boat shows Janet Frame playing with scale. Everything in Picton seems smaller as an adult, when the narrator wishes for the Picton of her childhood.

- Truth: NZ Truth was a New Zealand tabloid which ran1906-1988. From 4 July 1988 it was called New Truth & TV Extra. Started in Wellington by an English-born Australian man who had great success with the Sydney Truth. Stories comprised a trashy blend of sex, crime and radical politics at mainly working class readers.

- had one over the eight: very drunk

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE LAGOON”

In “The Lagoon”, a child visits her aunt in Picton. Assuming an autobiographical setting, the first person narrator has taken the train from Dunedin.

Is it time for Picton to have the conversation about changing its name? from The Spinoff. (The gateway to the South Island is named after a notorious slave trader who tortured a 13-year-old girl.)

The story opens and ends with the child thinking about childhood play at the lagoon. She visits during the day as well as at night, when the moon seems to appear in the water. She plays mothers and fathers and likes to imagine this moment will never end, that she will remain a child forever.

But a visit to see her Aunt in Picton after World War 2 changes all that.

Even Picton has changed since last time the narrator visited. Everything is smaller because she is herself bigger. The signs of progress seem even more stark when the aunt shows the young woman photographs of Picton how it used to be in the old days.

The aunt shows pictures of her grandmother and great-grandmother, who are both now dead. This is a solemn reminder that time marches forward, we all get old. The narrator sees herself as part of this long chain of women in her family and sees that she, too, will die someday. The view of her aunt looking at the window creates an unsettling mise en abyme effect, though the aunt, herself, seems at ease telling the story. The aunt remains oblivious to the unsettling effect of her revelations. (Look for windows and mirrors in stories with shifting perspectives.)

NEW ZEALAND TRAINS

During Janet Frame’s childhood, New Zealand ran a thriving passenger rail service. The first railway lines were built in the 1860s. If New Zealanders wanted to travel between cities, they took the train. The Main North Line ran between Picton and Christchurch, and the Main South Line between Lyttelton and Invercargill.

But private cars killed New Zealand’s historic passenger train industry. The last steam train service ran on 25 October 1971.

WHEN IS THE STORY SET?

We know this story is set after 1945 because that’s when the Main Trunk Line to Picton was completed. The opening of this new railway line is the reason for all the new tourists. Also the Māori musicians with their ukelele have stopped singing traditional Māori songs. Now they sing American songs, presumably having learnt them from American soldiers.

BEING-TOWARD-DEATH

This story is an example of Being-toward-death, which Heidegger talked about — that part of young adult development where you realise you, too, will die someday. We realise in early childhood that people die, but we don’t apply it to ourselves. The full weight of personal death is better understood around adolescence.

We know the narrator has had a realisation because the lagoon is ‘dirtier than ever’.

THE SYMBOLISM OF THE LAGOON

On a surface level reading, the lagoon is now ruined because the young woman’s great-grandmother murdered her husband by drowning him in there.

But what’s the symbolic significance of the lagoon? Lagoons are a small body of water near something larger (and might be seen as a child versus parent personification). Lagoons can dry up, revealing things beneath. Lagoons show you something, even if it’s your own reflection. When the narrator sees her own reflection mingling with the foliage growing at the water’s edge as well as with the celestial objects above, this is the very large, the human-sized and the small amalgamating; everything pulling together, completing a picture, or an understanding.

Lagoons illuminate but also hide. The mud obfuscates. Ironically, the lagoon no longer shows what’s underneath, but the aunt tells her something instead. She conveys salacious family lore, which might have been broadcast in the trashy tabloid newspaper, if it hadn’t been kept a family secret: That the young woman’s great-grandmother killed her husband when he left her for another woman in Nelson.

The narrator always suspected there was more to the lagoon than her grandmother was letting on. Like many characters in stories, she half-knew a truth.

She copes with this unwelcome filled-in knowledge by returning to early childhood memories of the lagoon how it used to be, where she can play happy heteronormative families and imagine the sandcastle is real.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST “THE VOYAGE”

For another story involving a little of Picton as it once was, read Katherine Mansfield’s “The Voyage“. In that short story, a little girl travels from Wellington to Picton on the ferry with her grandmother, across the Cook Strait between the North and South Islands. Katherine Mansfield was born in 1888 and Janet Frame in 1924, making Katherine Mansfield the generation of Janet Frame’s aunt.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST LORDE’S “RIBS”

Janet Frame evinced a terror of time passing in this story. Likewise, though Lorde is still young herself (around the age Janet Frame would have been when visiting her Picton aunt), she is old enough to have experienced nostalgia.

It drives you crazy getting old

Lorde, “Ribs”, Pure Heroine

“THE SECRET”

Janet’s older sister Myrtle looks like Ginger Rogers. This affects the fantasy she imagines for herself. Myrtle uses admiring younger sister Janet as her confidante. When she gets a boyfriend, only Janet knows. But when the boyfriend is revealed to be a regular guy with regular bodily functions which require a bathroom, Myrtle is no longer into him. She wants the romance, not the reality.

THE READING MATERIAL OF GIRLS IN THE 1930s AND 40s

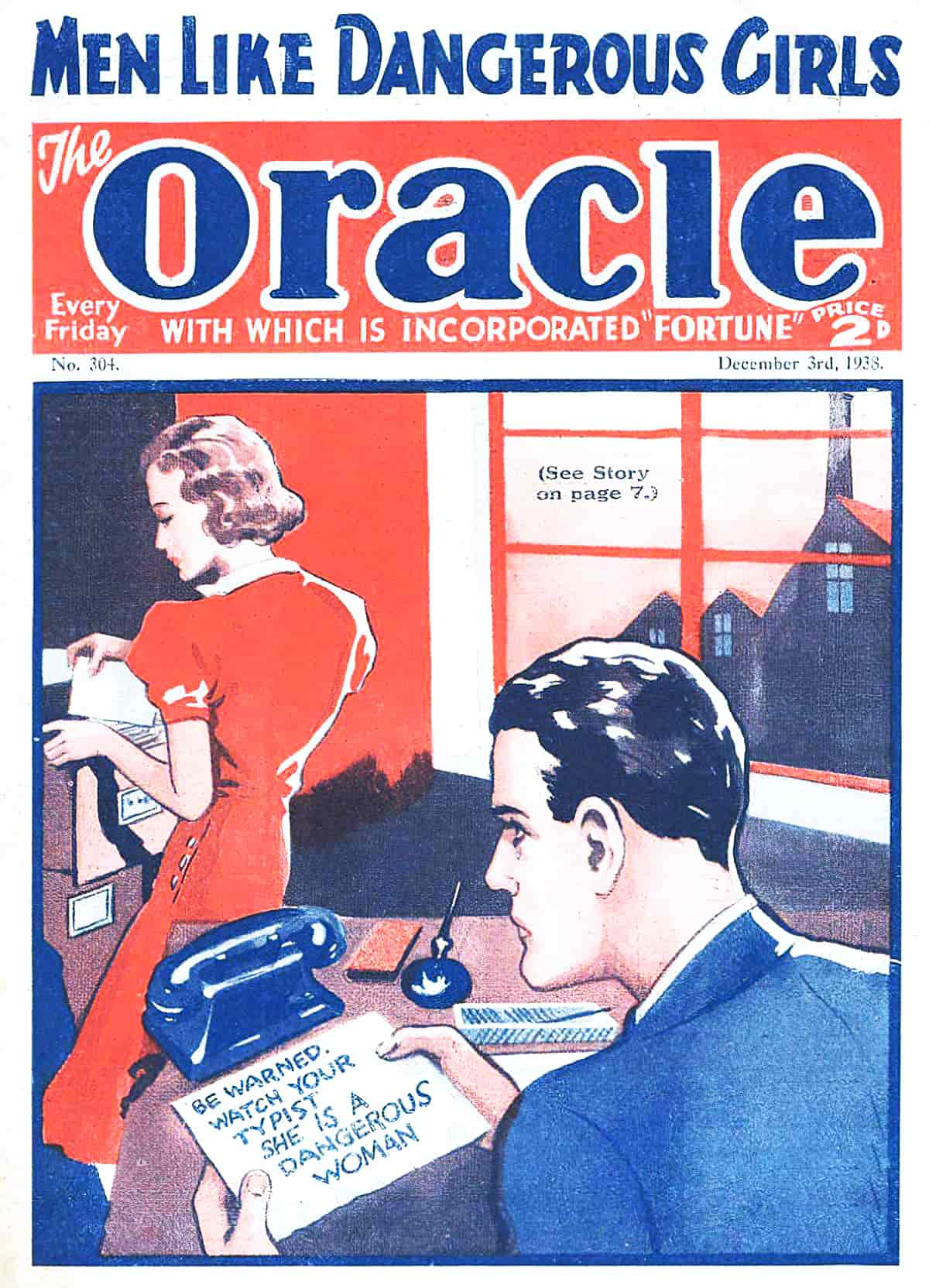

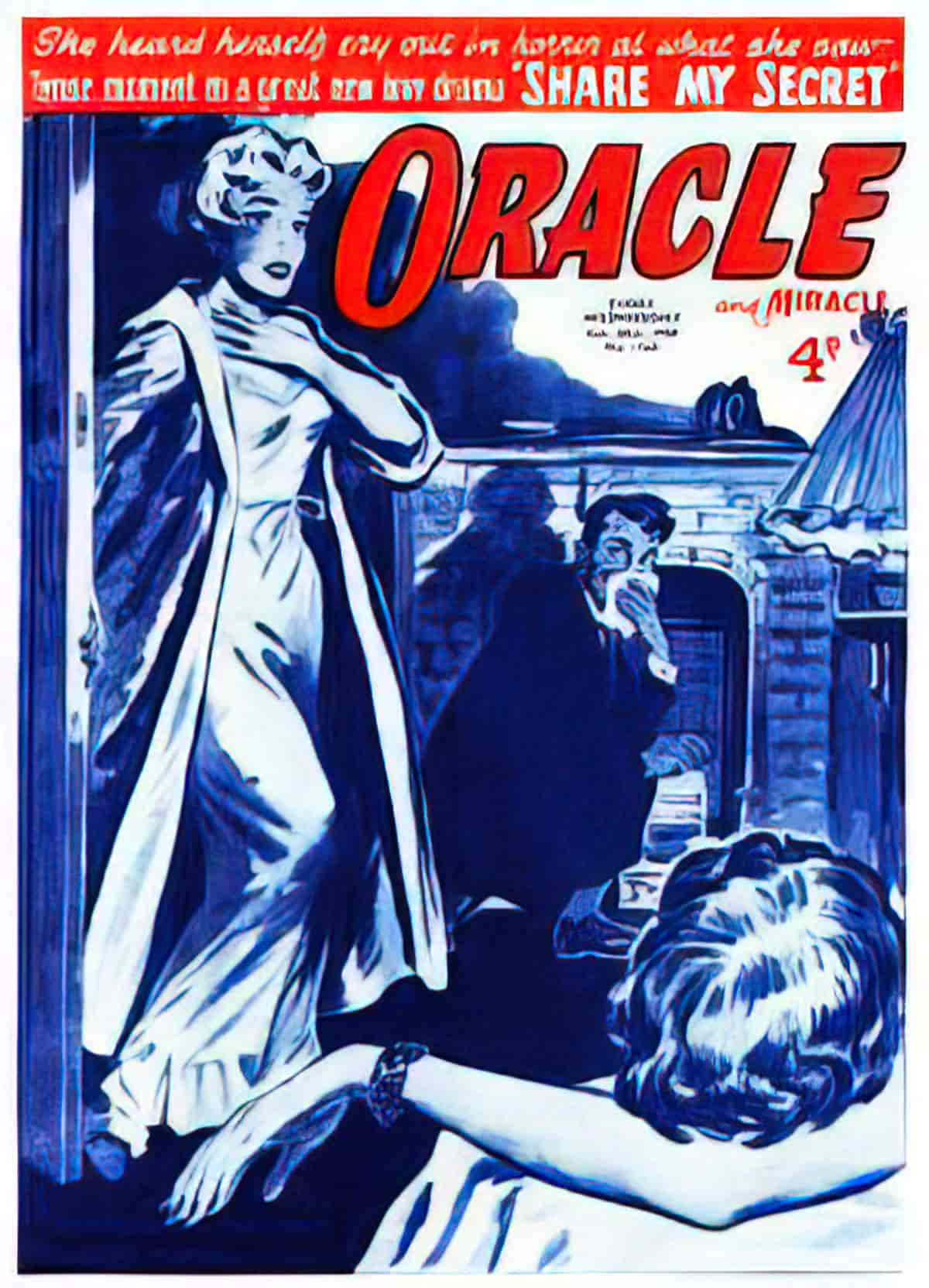

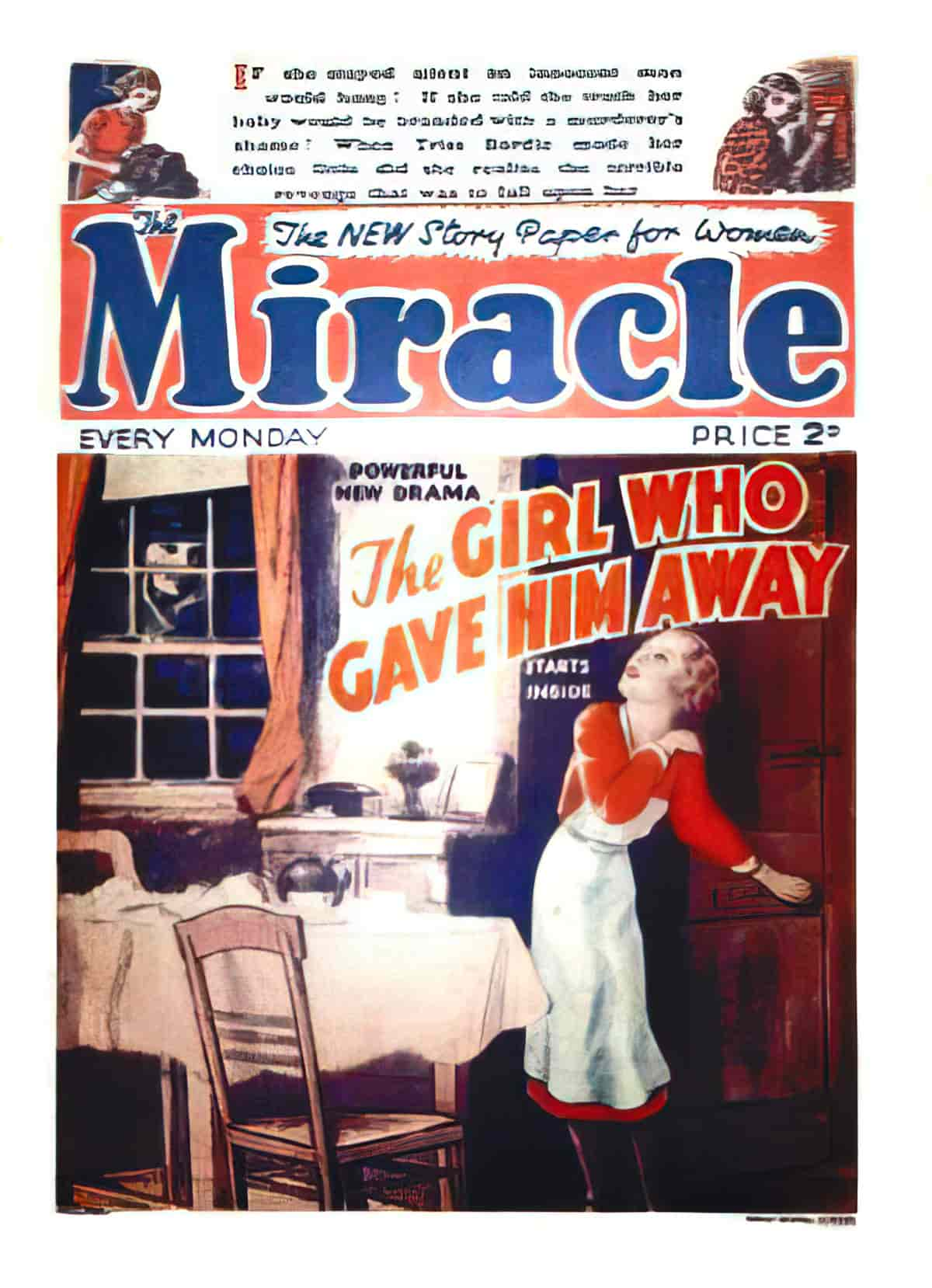

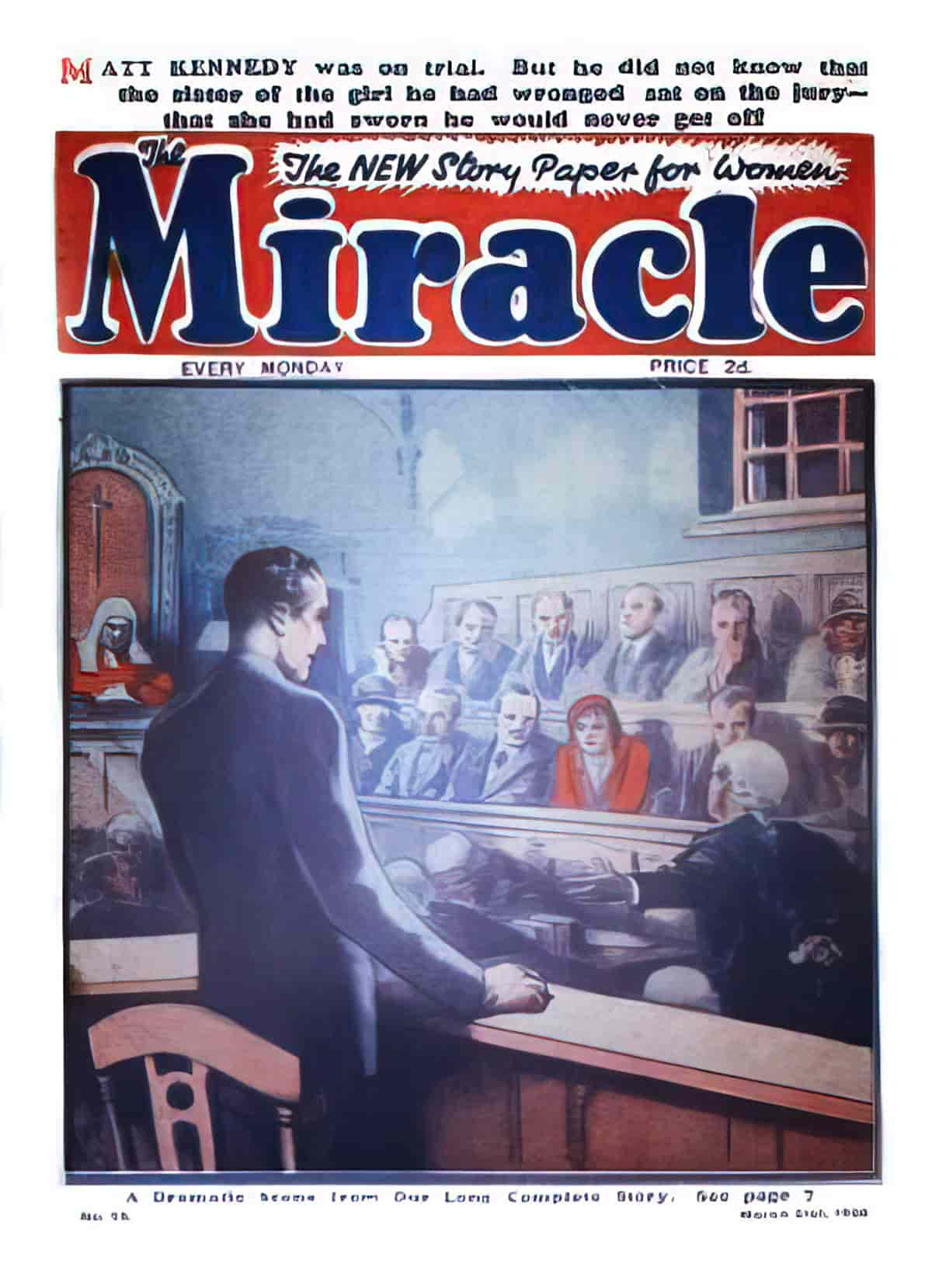

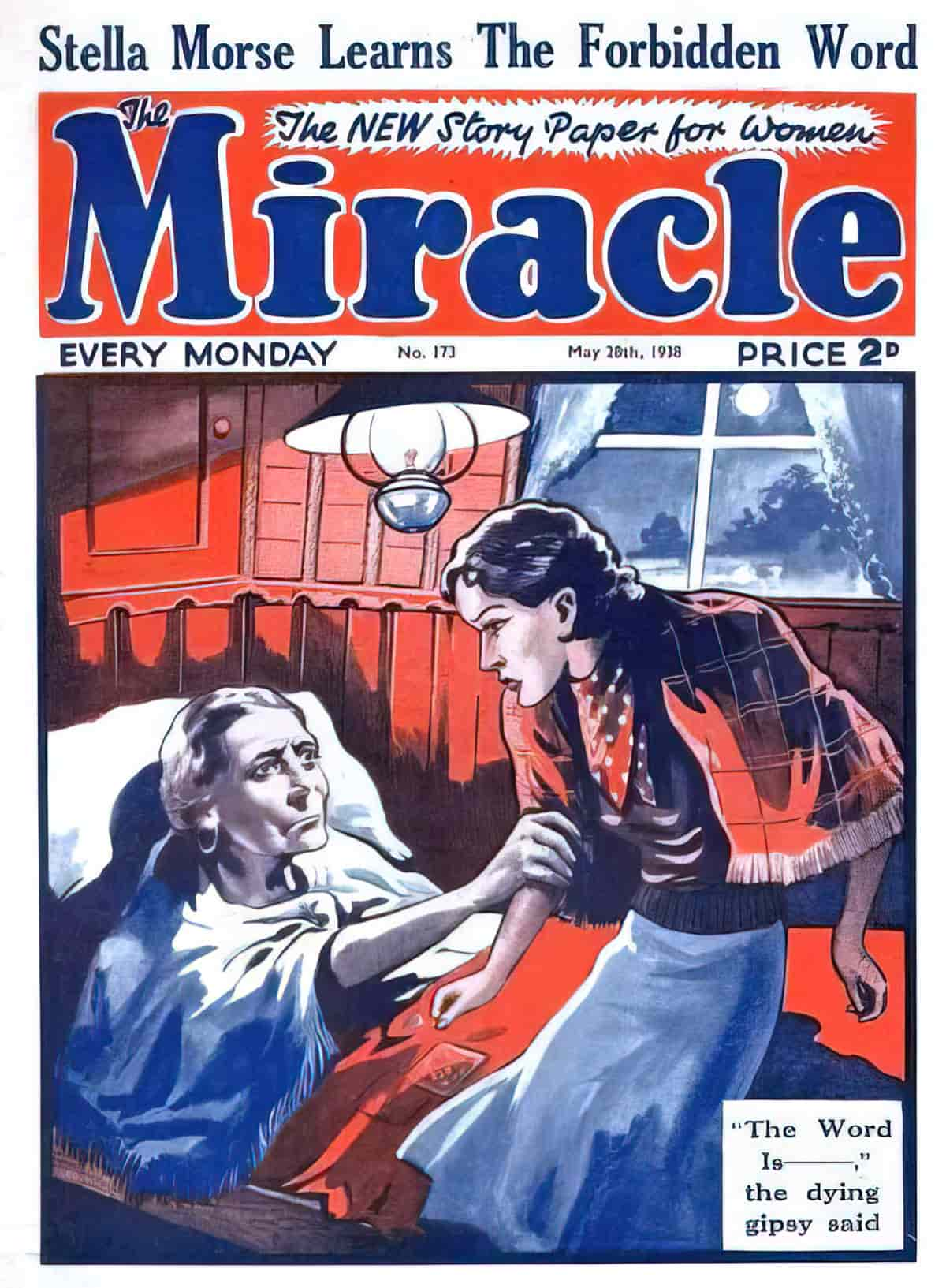

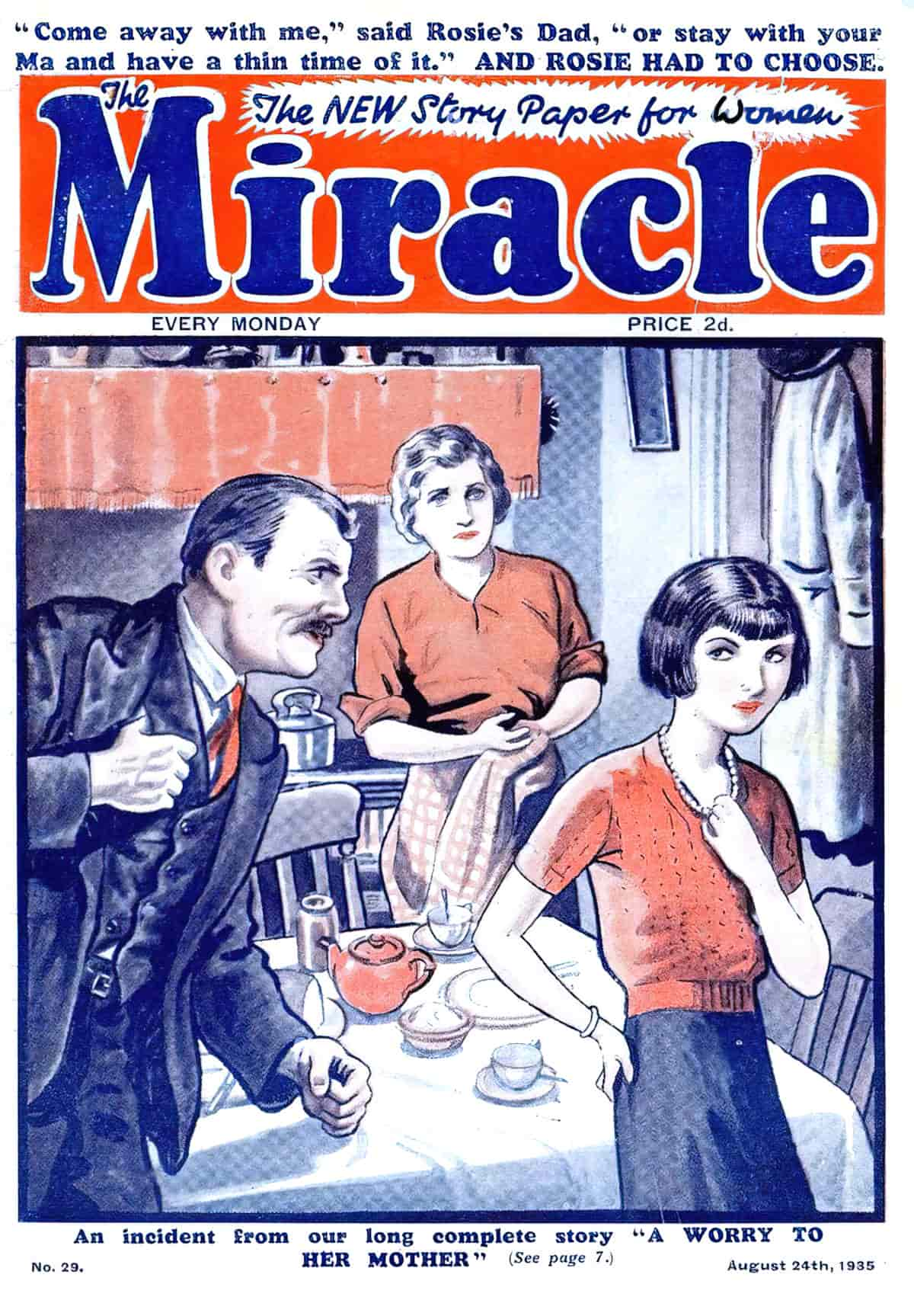

Myrtle’s romantic fantasies are fuelled by two pulp magazines in particular: The Oracle and Miracle.

The Oracle and Miracle were both marketed as “the new story paper for women”.

This 2010 article by Australian Dr Rosemary Montgomery tells us that much of what girls were reading in the war years has been lost. When looking at extant reading material from that era, we might assume girls were reading more wholesome authors such as Mary Grant Bruce and Dora Joan Potter. But when researchers include literature considered trash, girls were reading a wide variety of stories lost to us now.

Young teenagers liked The Girls Crystal but many of them were reading the harmless love stories in The Oracle and The Miracle at the same time. These two British story papers, inexpensive at 1d weekly, notable for their duochrome covers and drawn illustrations, were very popular in the first part of the war. Later came the American True Confessions-type magazines with full colour photographs on the cover and photographic illustrations to emphasise the ‘real life’ stories. They were expensive in Australia at 1 shilling in 1942 when girls like my respondent, Shirley P, were earning thirty five shillings a week.

Dr Rosemary Montgomery

After reading a few stories from copies for sale on eBay, I disagree with the assertion that these stories were ‘harmless’. As you might expect, the stories were salacious and not to be taken seriously, but in line with cultural messaging of the time, they trained young women to live their lives around men, and also to despise other women. Beautiful women are suspected of luring your boyfriend, for instance. The reader may subvert the intention and put herself in the fantasy role of the Bad Woman. Either way, the Madonna/Whore binary (marriageable vs unmarriageable) is upheld.

Today the magazines are hard to find because the magazines themselves encouraged readers to chuck them away:

[G]irls at home in Australia saw salvage collections as their means of supporting the war effort; and first into the salvage pile went their own weekly reading. The magazines themselves collaborated on this form of destruction. ‘Dig out those things you’ve put by…’exhorted The Oracle, one of the British romance weeklies in 1942. ‘Remember rags, rubber, metal and paper are specially important. Don’t put it off till tomorrow.’ What girl could fall to take the hint. My respondents recall being awarded certificates and medals for the pounds of paper salvage they collected.

Dr Rosemary Montgomery

Myrtle and Janet both imagine themselves movie stars but this is not positioned as sexually motivated. While the sisters imagine themselves in Hollywood, they also find beetles and small creatures in the yard and play with them — games in which they kill them with a magnifying glass. This childhood ritual will be familiar to many readers. Is this Myrtle and Nini experimenting with death, wresting back some control by determining how long the beetles live?

“The Secret” is very similar to “The Lagoon”: Both are about death, and its horrible reality that it comes for us all, even to young people (or, in “The Lagoon”, to people who were once young). Janet tries to suppress the spectre but cannot. It wakes her in the middle of the night. The Secret is between Nini and the mother, and it’s not clear whether Myrtle herself was fully informed about it. The Secret is also between Janet and herself.

Readers who know Janet’s biography will backshadow this one and realise that Myrtle did, in fact, die very young because of heart problems.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST “ROYALS” BY LORDE

At first glance, Lorde’s “Royals” seems to be saying the exact opposite. While Janet and Myrtle idealise the Hollywood stars they believe resemble them, Lorde outright admits, “We’ll never be royals,” and seems proud of it.

Yet the narrator of “Royals” also knows all about the “Gold teeth, Grey Goose, trippin’ in the bathroom/Bloodstains, ball gowns, trashin’ the hotel room.” Then, just like Janet and Myrtle, she’s “driving Cadillacs in [her] dreams”.

The reason Lorde’s narrator doesn’t care? Everything is possible in daydreams. “Let me live that fantasy.”

“KEEL AND KOOL”

Another story about coming to terms with family death, this time with fictional characters.

- Mr Todd: Takes a photo of the family on a picnic then says he’s off fishing. If he doesn’t catch a salmon he’ll get one from the butcher’s. Although he seems cheerful, as he walks away it is clear from his posture that he is suffering great loss.

- Mrs Todd: Has recently lost a child, her eldest, who was a young woman. The dead girl was called Eva. The mother is still in the depths of grief. A family photo reminds her that this is the first not to include Eva. More than her husband, Mother leans into her grief, though she can’t bring herself to use the word ‘dead’.

- Winnie Todd: a daughter. Her sister’s death has provoked anxiety. She worries that her father will drown in the river while he is fishing. She probably has curly hair like the author because she wishes her hair could hang down over her eyes so she could brush it away like Joan does. This reminds her of Eva, who also had long hair. There are unexpected advantages to her sister being dead, for example she gets to wear Eva’s pretty pyjamas.

- Joan Mason: ‘the girl from over the road and no relation’. She is sort of there as a replacement for the dead Eva. She was Eva’s best friend, not Winnie’s. She is apparently Spanish, which would make her very exotic. She wears a fur coat. (These characters are clearly autobiographical.)

Joan is the only one alive who has secrets about Winnie’s dead sister, even if those secrets are inconsequential. This angers Winnie. Joan is no replacement for her dead sister. The two girls argue about which of them knew Eva better. Winnie puts a barrier between them by passive-aggressively accusing Joan of being a liar, angry she knows so much about her own dead sister. Winnie accuses Joan of having a ridiculous backstory, which is comical against the backdrop of grief. ‘Your hair went green when you went for a swim in Christchurch and you had to be fed on pineapple for three weeks before it turned black again’. (To Winnie, even Christchurch is exotic.)

The Keel and Kool of the title is onomatopoeic. The seagulls sound as if they’re calling for friends named Keel and Kool who will never be found.

The story ends with Winnie a little afraid to return to her parents at the picnic because she imagines a scenario in which Joan Mason has told on her for being mean. Her parents are disappointed.

“THE BEDJACKET”

When I studied New Zealand English at Canterbury University in the late 1990s, our lecturer (Patrick Evans) warned us about taking his course further. “We focus on Janet Frame,” he said of his third years. “Most of them end up on anti-depressants.”

Did the fellow not need bums on seats? Anyway, I didn’t major in English lit, let alone in New Zealand English. (Kind of missed my calling, there, except I wasn’t ready for Janet Frame when I was a teenager myself.)

“The Bedjacket” short story is a small example of what our lecturer must have been talking about. This is the first story of the collection set inside Janet Frame’s mental hospital.

It’s a character study of a woman called Nan, who escaped from a similar institution up north and has been transferred to this one in the South Island because it is built like a castle (without the Medieval trappings) and she can’t possibly escape.

When a kitten is brought in for her, she names it after one of the doctors. She has been abandoned by her family and has no one else to name it after. Then she knits a bed jacket and treats it like a pet. Nan is a desperately lonely woman who doesn’t believe she should be in a psychiatric institution, and the bed jacket is all she’s got.

Forbidden to visit the shops to buy her Christmas presents, Nan asks another resident to buy a present on her behalf. But without her own family to give it to, she will be giving it to the nurse.

I see what our lecturer meant. Sunnyside Hospital was still in operation even as I listened to my lecturer talking about Janet Frame. It didn’t close until 1999. I remember what the place looked like. I saw it rarely, only when we visited one of my mother’s old friends who lived in that part of Christchurch. Somehow you could just tell by looking at it, terrible things happened inside. That Gothic architecture didn’t match the rest of New Zealand at all, with its bright blue skies and well-watered greenery.

“MY COUSINS — WHO COULD EAT COOKED TURNIPS”

Like lamb chops, turnips are an example of a foodstuff which is now expensive to buy but was once the cheapest fare in 20th century New Zealand. My teenager loves turnips and they’re a treat. I’m guessing Janet Frame means swedes. We ate them a lot growing up, too, mashed with the potato. I just checked: Here in Australia, a single small swede costs $1.38. (A single washed potato costs 81c.)

In any case, Janet Frame’s family feeds some of their homegrown turnips to the family, some to the cow. This means they associate swedes with cow food. I believe Americans feel this way about certain kinds of pumpkin which I would consider human food? Also I believe swedes are called rutabaga elsewhere, and swede is a shortening of Swedish turnip. They taste best if there has been a good frost, which makes the bottom of New Zealand’s South Island perfect growing conditions.

When the Frames visit the fancy cousins, they feel ‘fancy’ themselves. They’re wearing new clothes and ride first class on the train because their father works for the railway and secured free tickets.

But when they get to the cousins’ house, they’re required to eat cooked turnip, which they hate. This breaks them out of their fantasy, that they are more fancy than they really are. They can never escape the mundane realities of their social class.

This realisation brings Janet and her cousin Mavis closer together. Janet had previously considered her separate, another breed, far better-behaved and more refined.

“DOSSY”

Flash fiction about a girl who is admired by a younger girl — who assumes Dossy must live in a big flash house because she is a big girl — but pitied by the nuns in a nearby convent. The nuns know Dossy lives in a tiny house without a mother to take care of her.

Dossy herself is old enough to understand that she isn’t fit to hold the younger girl’s hand because she the younger girl is well-cared for and from a well-off family.

Compare with “The Doll’s House” by Katherine Mansfield.

“SWANS”

The childlike voice of “Swans” feels like stream-of-consciousness and highly reminiscent of Katherine Mansfield. It’s like a cross between Mansfield’s “At The Bay” and “The Wind Blows“.

Perhaps ‘stream-of-consciousness’ isn’t quite right. Like Mansfield was able to do, Janet Frame puts the narrative camera both inside and outside the young characters’ heads. When woman writers do this and tell stories from the point of view of children, their writing is frequently described as sappy or sentimental or dross, but it’s a sophisticated technique. When Frame describes the slater, for instance, we are down on the floor of the shed. We are in the child’s head. But the narrative camera also zooms out to a wide angle when we see the sky changing, when are shown the sea vista.

You know how it’s going to end. When a mother and her children leave for a day at the beach a kitten is terribly sick. One little girl can’t bear to leave it, but the mother insists it will be fine with milk under a blanket.

They take the train to the beach, with instructions from the father. But the mother has got directions wrong and they get off at the wrong station. They spend the day at the wrong beach, which is not at all what the mother expected. She expected other families with children and a fun playground. But here the beach is defamiliarized, as if it’s a different sea entirely.

The weather changes. There’s gazing out to sea at the ships, and contemplation of life and death (like “The Wind Blows”). And of course, when they get home, the kitten is dead.

Although the little girl suppressed her worries, the death of the cat had affected her entire day.

“THE DAY OF THE SHEEP”

The narration of this story is so unusual, at first I wondered if the story were being told from the point of view of a backyard bird. But no, this is a housewife on the edge of sanity.

A friend has come for a visit, having recently broken up with her husband. From Nora’s point of view, the narrator looks as if she’s content and happy with her husband, but Tom wants to sell the house. The narrator doesn’t want to because she’s lived her all her life.

The husband buys Tatts tickets (the old Lotto) because he strives for something better. At work he steals handkerchiefs from coats left behind. This is a very small life.

As is clear from the style of narration, full of sentence fragments and unexpected segues, the housewife narrator is experiencing disordered thoughts. This frame of mind prevents her wanting anything more than crisp, dry washing. Her state of mind is clear to Nora only through her hair, which the friend tells her to do something about.

The hair links woman to sheep. The narrator feels most kinship with the sheep, who mistakenly entered her washhouse earlier because it didn’t know where it was going, but finds itself wandering around aimlessly, in places sheep shouldn’t be.

“CHILD”

The language in this story reminded me of my grandmothers’ lexicon e.g. “pinny” meaning apron, and “corker” meaning “very good”. One nana used to play a game with us whenever we got something good, like a 20c dolly mixture from the dairy. She’d pretend to be a little kid and say, “I’ll be your best friend! I’ll be your best friend!” Childhood friends are easily made but not always genuine. So it is in this story.

Both of my grandmothers were subjected to run-of-the-mill cruelty and so it is in Janet Frame’s “Child”. The children are literally strapped for daring to breathe during class.

An unintended consequence of teacher cruelty: Children band together in unity. Because two girls were both strapped at once for the same minor thing, they are now best friends. We know they’re likely to fall out of friendship equally easily, but the end is merely suggested in this story. The narrator (a Janet Frame stand-in, of course) is bowled-over by the novelty of Minnie Passmore’s life. Everything about Minnie and Minnie’s house is wonderful, only because it is different.

Minnie invites Janet for a ‘playdate’ after school (not that it was called that, then, or even in my childhood). First, Janet must stop in at home and tell her mother where she’s off to. There, the mother is distracted and Janet is embarrassed. Janet’s mother accuses her of picking at the bread. The mother shakes her pinny as if in the company of lowly chooks.

Janet romanticises not having a mother at all, like Minnie, who lives with her grandparents because she has no mother and father. Old Mr Passmore takes them to fly a kite on the hill, where Janet can see her own house and continue to judge her own home life negatively.

It is up to the reader to understand that if Minnie has no parents, her life can’t be as rosy as it appears to little Janet’s first glance, and that Janet should feel lucky to have a loving, pinny-wearing mother who cares about things like who dug a mouse-sized hole in the bread.

Like a number of other stories in this collection, “Child” is about the shame of poverty, of your family who is on the fringes of polite society, and the escape into imagination — which can be at times unhelpful as well as a necessary coping mechanism.

“SPIRIT”

A man has just died. Told entirely in dialogue, he tells someone (some kind of after-death official) about his life. This after-death official is clearly not some omniscient god, because they don’t seem to know anything about Harry’s earthly life, including whether he has newspapers down there or not. (Harry mentions his newspaper obituary.)

Harry describes the routine, unremarkable life of a family man. He had dreams which were never realised. But he never expected them to be realised, anyway.

What did you most want to be?

Oh an inventor or explorer or sea captain.

And were you?

Oh no of course not, these are just fancies we get when we are little kids running around the garden playing at being grown-ups.

“Spirit”

(See also “Royals” by Lorde.)

Harry learns he’s about to be reincarnated as a leaf. What a comedown. He exclaims he used to be a man, with the body of an angel, and real thoughts and everything.

But the after-death official reassures Harry. He’ll be free of ‘blackbirds’ and he can always make a little silver* patch on the leaf, all his very own.

Reading this unusual piece of micro fiction, it’s easy to see a connection between fictional Harry, who has literally died, and Janet Frame’s dehumanisation inside the psychiatric hospital. Harry lives an ultra-routine life with suppressed hopes and dreams. He dies. Then he finds out how tenuous connection to humanity really was. ‘Human’ wasn’t his essence at all, if he can be sent back as a leaf.

In this reading, the ‘blackbird’ might be a stand-in for any sort of difficulty. “Sure, you have no autonomy, no real humanity, but at least you don’t have to worry about a thing. We know nothing about your life — nothing at all — but we’ll arrange every aspect of it for you. Leave it to us.”

(*Silver leaf is a fungal disease caused by Chondrostereum purpureum. It infects through wounds, mainly caused by pruning. Leaf silvering occurs during summer and fruiting bodies form from late summer.)

“SNAP-DRAGONS”

The story opens with a close-up description of snapdragons and bees, momentarily disorientated after crawling inside the flowers.

As explained in the text, the name “snapdragon”, comes from the flowers’ reaction to having their throats squeezed. The “mouth” of the flower is thought to snap open like a dragon’s mouth. It is widely used as an ornamental plant in borders and as a cut flower and does well in sunny gardens.

Ruth is about to be released from the psychiatric hospital in time for Christmas. Her mother has come to pick her up. Ruth realises that if she says goodbye quickly, she can mask the sadness and terror around leaving her fellow patients. One of the women misinterprets this as Ruth wishing to be rid of the ones left behind.

Janet Frame brings the story back to bees and their disorientation after crawling out of snapdragons. Will she be accepted back home? Will she be truly free, if everyone worries about where she’s going all the time? Is she ruined now, as the person who came out of the “loony-bin”?

Without using the word, Janet Frame is describing stigma.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN SHAME AND STIGMA

I recently heard an excellent explanation of the difference between shame and stigma from Julia Serano, promoting her new book Sexed Up. The short version: Stigma is contagious and permanent.

In common use, stigma and shame are often used in a similar way to refer to a sense of internalised inferiority or embarrassment for instance maybe being a member of a marginalised group or perhaps for engaging in sexual acts or having certain sexual desires deemed as bad or pathologized in society. So they definitely have that in common.

The reason why I use stigma throughout the book [Sexed Up] is because people have studied stigma. And in addition to maybe a sense of shame that I might internally feel, stigma is very closely associated with the idea of contagion.

When I say contagion I’m not talking about viruses or legitimate communicable diseases. I’m describing a type of magical thinking. When contagion is involved, people assume someone who is stigmatized… if they get too close to a member of that group that their stigma will rub off on me.

Erving Goffman, a [Harvard] sociologist from way back did a lot of work on stigma. He described that as courtesy stigma. Other people call that stigma by association. Anyway, people feel that not only is it contagious, but that people who are affected are permanently ruined by it. So it’s not just negative but it’s negative and permanent.

It became clear as I was working on this that this is how we see sex. For instance, a woman is a virgin, but once she has sex she is permanently contaminated by the experience. Or, if say someone was in a new relationship and their partner revealed that, “Oh, I used to be in a same sex relationship, or I used to be a sex worker,” even though those are past experiences, and sexual acts are fleeting, like they disappear over time, people might feel like that individual is permanently tainted by that. And by having a sexual experience with that person, they might feel their own sexuality might have been compromised.

We see that a lot when people have any kind of sexual interest in a queer person, or sexual experience with a queer person, people will often feel that their own sexuality or gender has been compromised. I believe that’s another example of this contagion working.

That might sound a little bit technical, but that idea of sex and stigma and contagion are all interwoven with one another. It comes up over and over when you look at different reactions to sex and sexuality in our culture.

Julia Serano at Vox Conversations talking about how society sexualizes us

INSTITUTIONALIZATION

Janet Frame also uses the imagery of bees and snap-dragon as a metaphor for what is now widely known as ‘institutionalization’: a chronic biopsychosocial state brought on by incarceration and characterized by anxiety, depression, hypervigilance, and a disabling combination of social withdrawal and/or aggression.

Institutionalization happens in orphanages, psychiatric facilities, prisons and anywhere freedoms are curtailed, basic life-support needs met. Once someone has entered this state, they may prefer life inside an institution, feeling unable to cope with life after release.

If you were free, did you always fly away?

“Snap-dragons”

(Strangely, a form of institutionalization seems to happen to some of society’s most privileged, as well, as for example when politicians start out their careers smart and free-thinking, then over decades learn to toe the party line, finally unable to think as individuals because too much is at stake.)

“MY FATHER’S BEST SUIT”

“My Father’s Best Suit” is a snapshot of New Zealand life during the Great Depression. If someone in your household had a job, you were still okay. Not everyone was equally affected by it. Mr Frame has a job, but people are unable to get things they were able to buy before. In this case, grey thread to repair the father’s best suit. The trousers on the “best suit” are shiny and worn. Depression or not, the Frames were not a wealthy family. The girls wear hand-me-down dresses from an auntie. The dresses don’t fit properly.

Janet Frame lists the games they played growing up across wartime. The wider world in turmoil was reflected in their thinking, but in childlike ways:

We did plenty of fighting. We had Wars. We wrote in invisible ink with lemon, and we wrote spidery writing with green feathers, and we wrote with the blood of dahlias.

“My Father’s Best Suit”

I also remember writing “spy letters” with lemon juice. We lived in Motueka for a while, where lemons are plentiful. You use lemon juice and a cotton bud to write a letter. It drives to invisible, but reappears once heated up, for instance under a hot iron. It sounds better than it is. Growing up in the 1980s, I didn’t connect this activity to the secretly encoded letters of wartime. In fact, I learned about this in a book about magic tricks (which were all terrible and impressed none of my friends).

The spidery writing in green feathers is more baffling, and perhaps specific to the Frame Family idioculture. A number of New Zealand birds have green feathers, though they tend to stick to the forest. Perhaps these ones were plucked out of a boa, handed down from the aunt.

“A BEAUTIFUL NATURE”

Ah, another super-affecting character study which left me with a lurch in the gut alongside the earlier story, “The Bedjacket”.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “A BEAUTIFUL NATURE”

Edgar is a single man who lives a quiet life in a boarding house along with a number of women. He is widely regarded a ‘sissy’ (code word for queer). He works at the tannery but is sacked for no reason.

He only realises after the conversation with his boss that he’s been given the sack, which seems to me a typically autistic experience of the world — a slower processing speed, since social interactions must be understood cognitively rather than intuitively. (If Janet Frame wasn’t autistic herself, I’ll eat every one of my hats, raw.) If Edgar is an autistic character, it makes sense that he fails to conform to hegemonic masculinity and that he is regarded as ‘slow’.

NARRATION IN “A BEAUTIFUL NATURE”

It’s unclear how much of this story is ‘truth’ and how much is ‘hearsay’ within the world of the story. The narrator seems to be someone who lives in the same small town. For instance, Edgar never admits he lost his job because he was sacked. He says it’s because of health reasons. Somehow the narrator knows the real story, but do they? Presumably this knowledge was garnered via neighbourhood gossip. The boarding-house women are archetypal gossiping dames and they find odd Edgar an amusing topic of speculation.

For no good reason, Edgar loses his next job, too. He puts thread onto spools at the factory. It’s hard to remember such brain-numbing jobs existed until recently. (I’m reminded of Charlie Bucket’s father from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, whose job was to screw the lids on tubes of toothpaste.)

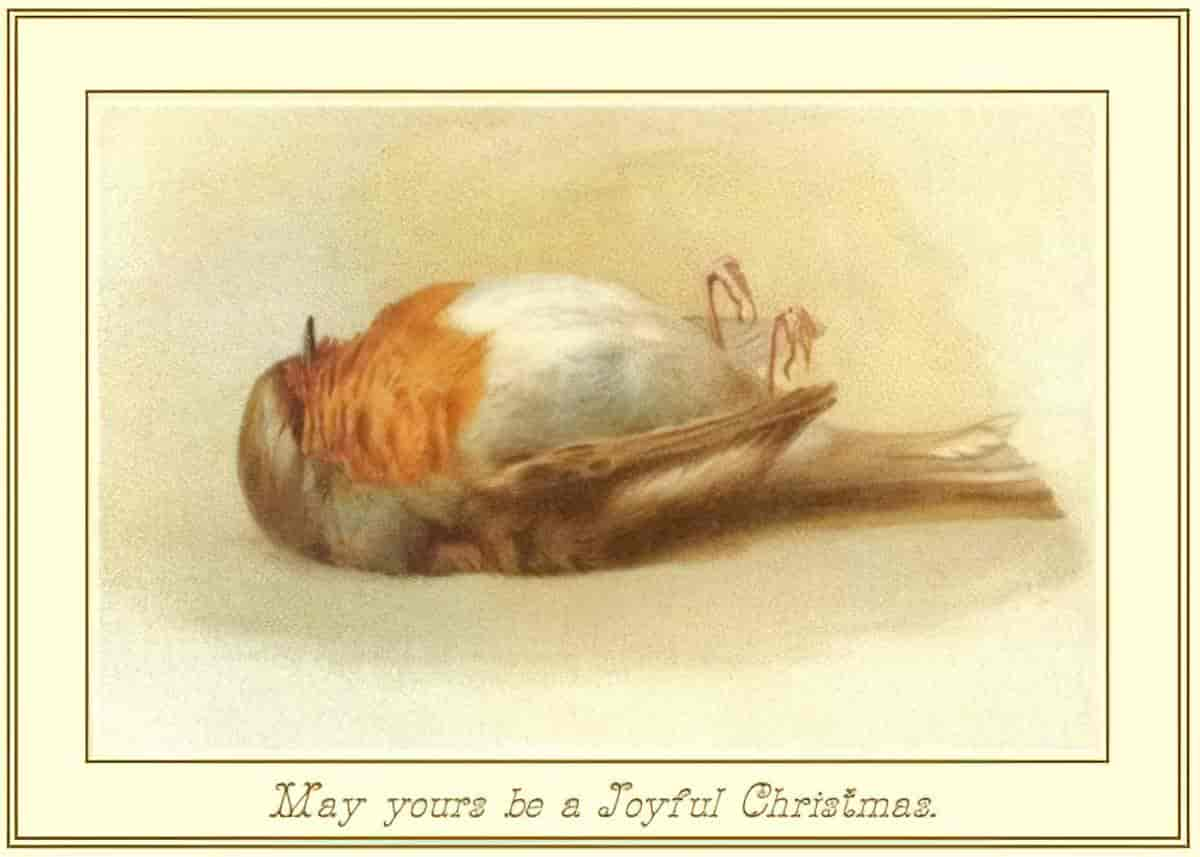

Edgar has bought pretty Christmas cards for the women at the boarding house. Preparing greetings cards is a femme-coded activity and the job of housewives, so of course the dames find this amusing in a single man. Upon receiving her card, the eldest dame notes that Edgar “has a beautiful nature”.

PATHOS

What makes this short story so affecting? Well, Edgar is the classic underdog, of course. Nothing goes right for him. The injustice of unfair dismissal is maddening to 21st century readers, who are now (somewhat) protected by labour unions from merciless corporate fatcats who will happily sack staff just before the holiday season.

But Edgar’s Christmas cards are the pearl of the story. An act of unexpected kindness always does it for me in stories.

“ON THE CAR”

“On The Car” is a short sketch of people riding a train during a hailstorm. A drunk guy gets on, making everyone a little uneasy.

Janet Frame also describes a young woman reading a film magazine. The omniscient narrator also knows which article she’s reading. She’s reading a biographical fluff piece about a famous actor.

Another man has ‘the mien of Te Rauparaha’ (1768–1849), Māori rangatira (chief) and war leader of the Ngāti Toa tribe. New Zealanders all know about Te Rauparaha from history lessons in school.

This sketch serves as evidence of Janet Frame’s keen observational skills, and her sensitivity to emotional shifts in a group of people.

“TIGER, TIGER”

Any repetition of “tiger” calls to mind the poem by William Blake.

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

William Blake

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

(Basically: What kind of God would make a scary creature like a tiger? Fire equals fear.)

The narrator’s childhood fear: That she won’t get a present for Christmas. That she’ll never get a tiger, which she has fixated on. She can’t imagine how she has lived so long without one.

The story reveals itself as nothing more than a repeating childhood dream, described by a more knowing, older narrator who now knows that the tiger fantasy was just a fantasy.

But then we are tricked into reading what we think is a real Christmas eve experience, only to learn that we are once again in fantasyland alongside the fictional narrator. We are stuck in this looping dream with her. We understand something of the childhood fixation because we’re feeling it ourselves.

This story feels relatable. I really wanted a monkey after seeing Curious George on TV. Also, when I was two years old, wearing nothing but a bib and nappies, I escaped my parents’ notice and went off for a trot along the main road. When I was returned to my parents, apparently I explained that I’d been off “to see the lions”. I remember nothing of this. The story was recounted to me numerous times later. In any case, I think most people would have one or two stories like this from childhood. Then again, if I hadn’t escaped the house, I’d never know I’d ever been interested in tigers because my parents would never have asked what I was thinking.

Many of our childhood desires are lost to us. What else had I wanted, before I was old enough to form memories? Which of my memories have been lost? We really only remember the repeating experiences. Tiger, tiger, on repeat.

“JAN GODFREY”

Two questions: Who the hell is Jan Godfrey and who the hell is Alison Hendry?

I am writing a story about a girl who is not me.

“Jan Godfrey”

All the way through this collection, it has been very tempting to read 100% autobiographically, but then, that would be a mistake. This is especially tempting if you’re familiar with the autobiographies and biopic of Janet Frame’s life. It’s impossible to believe she wasn’t on a train with the drunk man, that she didn’t grow snap-dragons in her garden, that she didn’t know a man called Edgar who gave out Christmas cards.

But that would be a mistake.

This story reads like someone warming up their typewriter. I’m sure there’s more to it than that, but not on the surface.

The onomatopoeic sound of the magpies on the final page comes from a famous New Zealand poem by Denis Glover (1912-1980). Primary school students of Janet Frame’s generation had to memorise it, though the tradition of memorising poetry for recital has gone by-the-by.

“SUMMER”

This very short piece baffles me because Janet Frame paints a picture of an upper class boy practising solitary cricket in his manicured yard. But when the father comes out to console him, the boy speaks with a working-class dialect. I have no idea what this juxtaposition means, or if I was meant to notice it.

Cherries and changing weather are repeating motifs throughout this collection.

I recall being a kid myself, and briefly owning a small, super-bouncy rubber ball. It was exactly the colour of crab apples, which I realised with a disappointing jolt after bouncing it too wildly near a crab apple tree. It was the end of summer and crab apples covered the ground. There was no way in hell I was ever finding that red bouncy ball again, not among all those identically coloured cherries.

I suspect there’s something to be said here about the end of summer symbolising the end of childhood, and a precious lost toy standing in for a childhood which will never come again.

Growing up a little at a time, then all at once.

Lorde, “Secrets from a Girl (Who’s Seen it All)”

“MISS GIBSON — AND THE LUMBER-ROOM”

A twenty-one year old ‘sort of’ university student writes a letter to a primary school teacher. (This is clearly Janet Frame herself.)

The teacher had read a sentimental, tear-jerker of a short story about an old man recalling fond memories after fossicking through items in his lumber-room. A lumber-room is a room in old, aristocratic houses where precious items are stored when not-in-use. Obviously, the teacher was using this as a mentor text, meaning her students to write about precious items from their own homes, whatever they were.

But Janet took the idea and ran with it. Thinking she was expected to have a lumber-room like this old man, ashamed that she didn’t, Janet wrote as if she lived in a country mansion with servants and gardeners, the whole kit and caboodle.

Now she writes to that teacher as an adult, explaining what a liar she was (as if the teacher wouldn’t have known, haha). The gag is that this is obvious all along, yet the story concludes, ‘If you really want to know, we didn’t even have a lumber-room’.

Saki also wrote a short story about a lumber-room (1914) but it’s not the one Janet Frame’s teacher read to the class. (Saki’s is a very good story, especially when you realise its significance to the queer community.)

“A NOTE ON THE RUSSIAN WAR”

It’s 2022 and I’m sick of Russian wars, but here we are.

We were just Russian children on the steppes singing tra-tra-tra

“A Note on the Russian War”

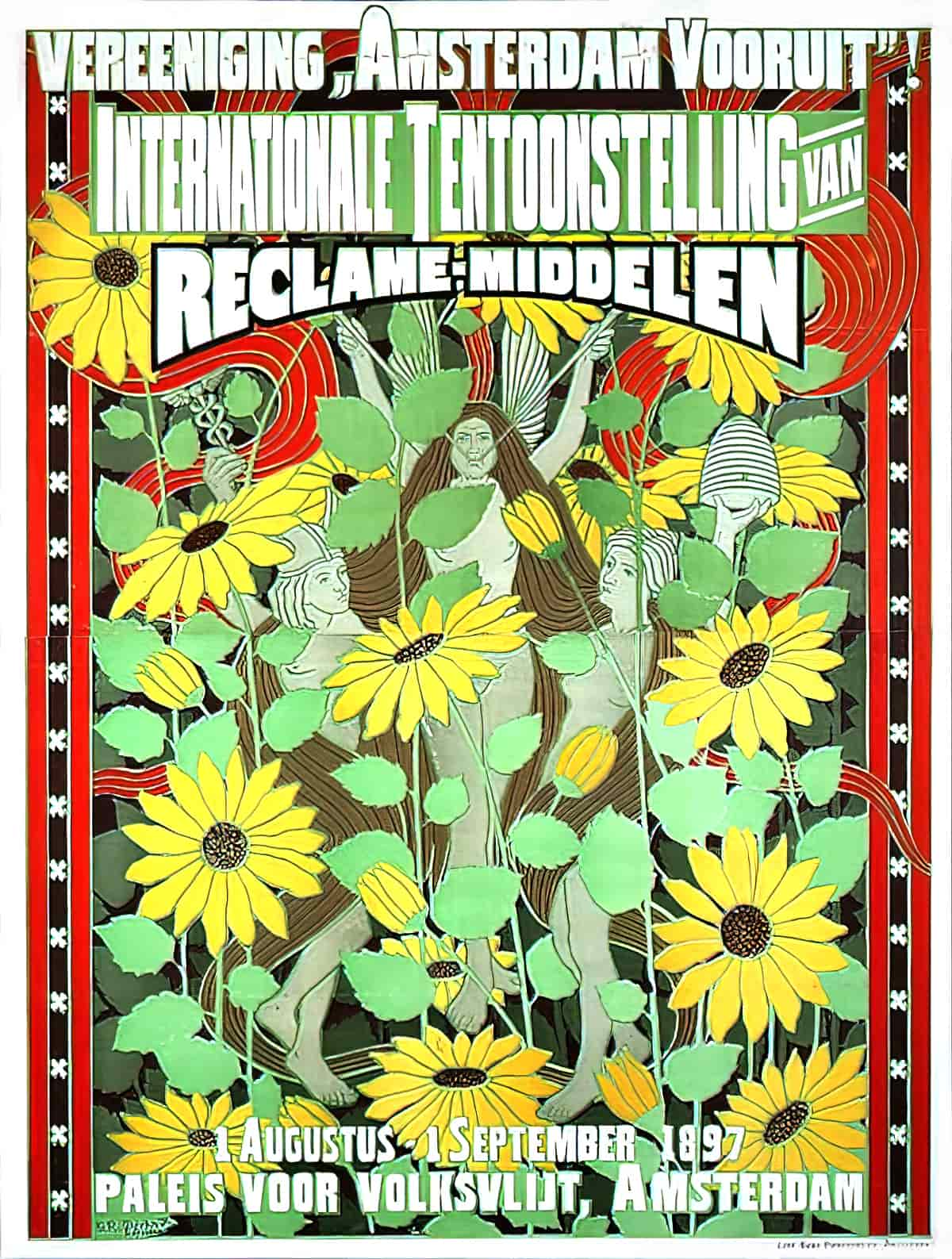

Janet Frame had no connection to Russia, but this story seems to comment on the reality that the common people of enemy countries were innocent. While their leaders start wars, they focus on sunflowers.

Sting did a similar thing decades later: “Russians (Love Their Children, Too)“

“THE BIRDS BEGAN TO SING”

Sing a song of sixpence,

A pocket full of rye.

Four and twenty blackbirds,

Baked in a pie.

When the pie was opened,

The birds began to sing;

Wasn’t that a dainty dish,

To set before the king?The king was in his counting house,

Counting out his money;

The queen was in the parlour,

Eating bread and honey.

The maid was in the garden,

Hanging out the clothes;

When down came a blackbird

And pecked off her nose.They send for the king’s doctor,

“Sing a Song of Sixpence, Nursery Rhyme

who sewed it on again;

He sewed it on so neatly,

the seam was never seen.

This nursery rhyme always scared me. Alongside Daphne du Maurier and Alfred Hitchcock, and New Zealand’s surprisingly vicious magpie swoopers, it did nothing for my feelings regarding birds.

But the narrator of this story isn’t so much afraid of the birds as frustrated by them. The birds are singing something — they must think it important — but the narrator can’t work out what they’re telling her. She goes on a mythic journey up hill and down dale, in a miniaturised landscape but achieves no insight even after arriving back home to her little house.

Why can’t the birds tell her what they’re singing about? She could transliterate their song for human consumption.

And as soon as she tells them this, they are quiet.

Some things must remain a mystery. Humans have a sense of entitlement, but that doesn’t mean our wish to understand everything about the world will ever be granted.

“THE PICTURES”

This feels like going to the picture theatre in the 1930s or 40s, when everyone was required to stand and sing “God Save The King”. (And now we have a king again.)

Janet Frame presents the picture theatre as a comforting heterotopia, where the same sequence of things always happens, and where romantic stories all end the same way. Patrons can enjoy a cathartic experience, crying in the dark as you hope the lights don’t come up before you’ve wiped away your tears.

The old woman and the little girl return to bright daylight from the darkness of the theatre, which is a little discombobulating. The grandmother has had an emotionally affecting experience, but the little girl in the red cap is only interested in the peppermint lolly.

“TREASURE”

Pair “Treasure” with “Miss Gibson — and the Lumber-room”. Both stories are about a child at school imagining she is wealthy beyond imagination. In this one, marbles are rubies and diamonds. Children come from all around to play with her. She gets a special holiday from school to accommodate her popularity.

Even before the kicker at the end, little ironies tell us this isn’t a fantasy story. No one is rich even in the veridical world of the story. The little girl uses the family jewels to buy her father new glasses. (A genuinely wealthy father wouldn’t need his child to arrange him new glasses.)

If you’ve read Janet Frame’s To The Is-land or seen Jane Campion’s An Angel At My Table, you’re probably remembering the scene in which Jean steals money from her father’s pants pocket and uses the coins to buy chewing gum. She gives gum to everyone in the class then tries, unsuccessfully, to lie her way out of trouble.

Jean’s teachers didn’t seem to understand what is so clear to us now: This was a little girl expressing generosity in the only way she knew how. This was probably also a little girl with little self-worth and significant poverty shame struggling to build friendships at school. In this story, she imagines buying glasses for her father so he can see better. Again, this is Jean taking care of others.

“THE PARK”

It wasn’t clear to me at first that we were no longer with Janet in primary school, but in the psychiatric hospital. Adults in the ward have the imaginations of children, not as play but as a necessary escape. The Park was mentioned in an earlier story. It’s a grim, unpleasant place.

Janet seems to realise for the first time here that a patient called Helen has a rich, imaginative world, like herself. Unlike Janet, Helen tips into psychosis (or perhaps it’s just sheer desperation) and tries to run escape the ward. She says she’s going home.

She doesn’t get far.

“MY LAST STORY”

Fortunately this wasn’t Janet’s Frame’s “last story” despite the declaration. This piece does explain why she doesn’t punctuate dialogue in the conventional way. At least, it explains she really detests it.

Various other writers integrate dialogue into their stories like this, without speech marks and he said, she said. Cormac McCarthy is one, though his punctuation i inconsistent (fine, leave out apostrophes, but leave all of them out.) Sally Rooney is another. Rooney has explained, when asked, that she doesn’t like anything on the page to call attention to itself. She initially wrote her first novel with speech marks, subsequently took them out, and realised her work was perfectly understandable without them.

Might this be Janet Frame’s reason, too? I somehow doubt it. I don’t expect Janet Frame was going for minimalism. With Janet Frame, I feel there’s no real distinction between what goes on in the mind and what gets voiced between people, because all of it forms the way we interact in the world. What goes on inside our private minds is as important — if not more so — than what goes between the speech marks. What does it matter if something is voiced or not? There are other ways of reading people, and throughout this collection, Janet Frame has shown us how she did it. This book proved to those who considered her mind vacant and useless that she enjoyed a rich interior world.