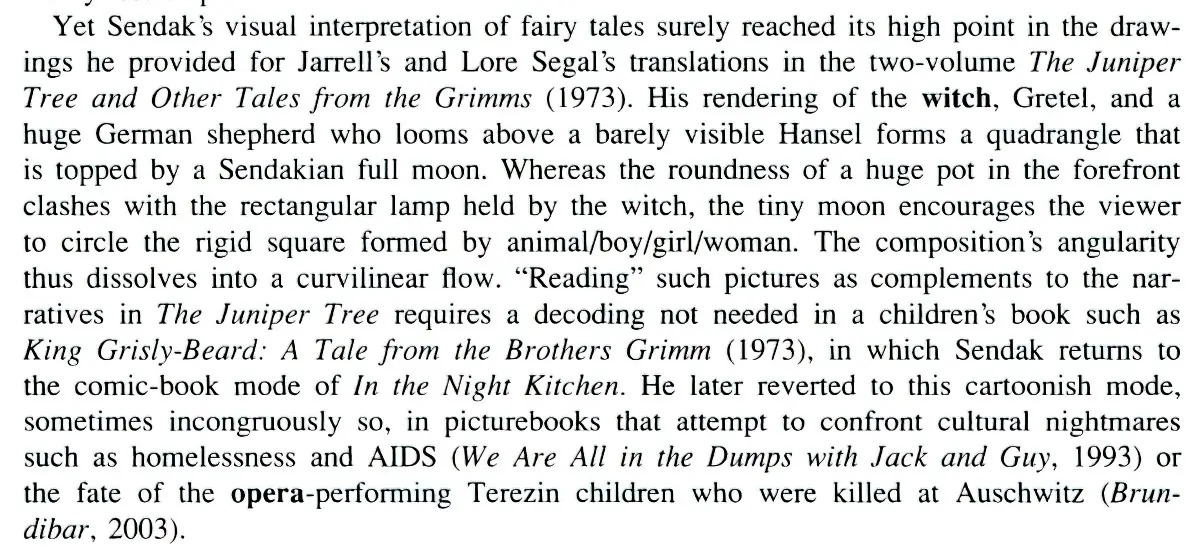

“The Juniper Tree”, as told by the Grimm Brothers, is a horrible tale. I don’t have a problem with gruesome. I can deal with fairytale cannibalism. The murder of the boy is comical rather than realistic and he comes back to life anyhow. No, “The Juniper Tree” is horrible for its symbolic annihilation of the mother. This is a tale written by men, for men, to reassure men of their dominance within the family hierarchy. Though it draws directly on a long history of tales in which children are fed to parents, the Grimm version inserts an extra level of female erasure.

This goes a long, long way back in history. “The Juniper Tree” is a newer take on a couple of ancient Greek stories. Medea took revenge on her husband by stewing their children. Season that story with the tale of Philomel, who transformed into a bird to sing about being raped by her brother-in-law. So her sister chops up the kids to feed to rapist dad. Because what did medieval humans use as stories? Europeans were well-schooled in the myths of Ancient Greece. It’s natural that these myths became basis for what we now call fairytale.

The Pennywinkle ghost story from the Ozarks is a ghost story riff on “The Juniper Tree”.

If you’d like to hear “The Juniper Tree” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “The Juniper Tree” was published March 2019.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE JUNIPER TREE”

This is the story of a family and a commentary on family structure. But the hero is the son/father who — for symbolic purposes — are one and the same. Literally. I mean, the father eats the son, incorporating him into himself. The hero is ‘the male of the family’.

WEAKNESS

Though this is a modern interpretation, the shortcoming of the father is that the woman and daughter run the household. The women may be indentured — unsupported even if they do want to go out into the world and work outside the kitchen — but since women do work in the kitchens, women are also in charge of what the family eats. This gives women some power, and must therefore lead to some dark fears among men. Food, of course, symbolises something bigger: nurturing. The women have to do all the child-rearing, but they also have the privilege of doing all the child-rearing.

The great shortcoming of the father: He doesn’t get to control what goes on at home. He goes out to work. While he’s away, the women could get up to all sorts. And they do. Oh, how they do.

DESIRE

The father wants a more secure role within the family. He wants to know he is the father of the children; he wants to be involved in nurturing (and controlling) them.

OPPONENT

The women. Women in general, symbolised by the second wife and the mean daughter who like nothing better than to kill boys and feed them to men.

PLAN

It is the bird version of the son/father who has the plan to dispose of the female characters altogether. He collects a variety of things by singing his truth in the song. Then he takes them to the father. This way, the father will know he’s still alive.

BIG STRUGGLE

The bird drops the millstone onto the mother’s head and kills her.

ANAGNORISIS

The father and Marlene learn what a wicked woman Marlene’s mother is, and so they are pleased when she is killed in an act of retributive justice.

For me, the revelation is that a happy ending in the culture of this story means killing off the woman (the second one), who is too powerful in her femininity to bear.

NEW SITUATION

Father, little brother and Marlene are happy — well, at least until the son inherits the entire house in a culture of primogeniture which excludes women and girls. And then who knows. I suspect the father will eventually dispose of Marlene, too, when she hits adolescence and becomes a reproductive threat.

JUNIPER AND BIRTH

“The Juniper Tree” is a fairy modern tale (though as shown above, its inspirations are ancient). But in the medieval era, people used herbal remedies which have since been lost to us. Some of these were surprisingly effective (experimental medicine wasn’t against any law, so I guess that helped move things along). For instance, willow bark was given to patients with fever — much later, this lead directly to the invention of aspirin. And juniper was used to promote contractions during birth. I do wonder if the people who told early versions of The Juniper Tree knew of the connection between birth and juniper as medication. For a modern audience, there’s nothing feminine about juniper — but was this story an attempt to redistribute (re-)birthing to men?

Other writers have made the most of the link between femininity and the juniper tree. Monica Furlong named her girl hero ‘Juniper’ in her Wise Child series, which is one of those books with a cult following and which should be widely known, but which is sadly out of print.

UNUSUALLY VIVID DESCRIPTION IN “THE JUNIPER TREE”

Usually in fairytales:

Imagery and description: there is no imagery in fairy tales apart from the most obvious. As white as snow, as red as blood: that’s about it. Nor is there any close description of the natural world or of individuals. A forest is deep, the princess is beautiful, her hair is golden; there’s no need to say more. When what you want to know is what happens next, beautiful descriptive wordplay can only irritate.

Philip Pullman

But “The Juniper Tree” is unlike other tales anthologised by the Grimm brothers. The imagery is very clear, probably because it was sent to the Grimm brothers by Achm von Arnim after being written down by Philipp Otto Runge. It is already, therefore, more of a literary fairytale than those which came from the oral tradition. Philip Pullman doesn’t seem to share my own distaste for the tale:

In [“The Juniper Tree”] … there is a passage that successfully combines beautiful description with the relation of events in such a way that one would not work without the other. […] the passage I mean comes after the wife has made her wish for a child as red as blood and as white as snow. It links her pregnancy with the passing seasons:

One month went by, and the snow vanished.

Two months went by, and the world turned green.

Three months went by, and flowers bloomed out of the earth.

Four months went by, and all the twigs on all the trees in the forest grew stronger and pressed themselves together, and the birds sang so loud that the woods resounded, and the blossom fell from the trees.

Five months went by, and the woman stood under the juniper tree. It smelled so sweet that her heart leaped in her breast, and she fell to her knees with joy.

Six months went by, and the fruit grew firm and heavy, and the woman fell still.

When seven months had gone by, she plucked the juniper berries and ate so many that she felt sick and sorrowful.

After the eighth month had gone, she called her husband and said to him, weeping, ‘If I die, bury me under the juniper tree.’This is wonderful, but it’s wonderful in a curious way: there’s little any teller of this tale can do to improve it. It has to be rendered exactly as it is here, or at least the different months have to be given equally different characteristics, and carefully linked in equally meaningful ways with the growth of the child in his mother’s womb, and that growth with the juniper tree that will be instrumental in his later resurrection.

However, that is a great and rare exception. In most of these tales, just as the characters are flat, description is absent. In the later editions, it is true, Wilhelm’s telling became a little more florid and inventive, but the real interest of the tale continues to be in what happened, and what happened next. The formulas are so common, the lack of interest in the particularity of things so widespread, that it comes as a real shock to read a sentence like this in “Jorinda and Joringel”:

It was a lovely evening; the sun shone warmly on the tree trunks against the dark green of the deep woods, and turtledoves cooed mournfully in the old beech trees.

Suddenly that story stops sounding like a fairy tale and begins to sound like something composed in a literary way by a Romantic writer such as Novalis orJean Paul. The serene, anonymous relation of events has given way, for the space of a sentence, to an individual sensibility: a single mind has felt this impression of nature, has seen these details in the mind’s eye and written them down. A writer’s command of imagery and gift for description is one of the things that make him or her unique, but fairy tales don’t come whole and unaltered from the minds of individual writers, after all; uniqueness and originality are of no interest to them.

Philip Pullman

There’s another rare example of a fairy tale which has such specific description that the characters are individualised, and that is Baba Yaga.

FURTHER READING

Katherine Langrish explores fairy tales, ballads and folk tales. She reflects on the role of women in fairy tales, discusses specific tales such as ‘Briar Rose’ and ‘The Juniper Tree’, and looks at wider themes of White Ladies, Water Spirits, Fairy Brides and many more.