“Jaunt” (noun): a short excursion or journey made for pleasure. In my Australian dialect, the word ‘jaunt’ typically refers to an unnecessary trip made for an important stated purpose but which is actually just a waste of taxpayer’s money. I’m not sure if you find this usage much in other English speaking countries, but if you search for “political jaunt”, the entire first page of results are written by Australians. “Junket” means the same thing in this context*. If years of media consumption have taught me anything, Americans use the word ‘boondoggle’ instead.

“The Jaunt” is also a science fiction short story by American author Stephen King. Even by King’s standards, this narrative is famous for its shocking ending. Read it in King’s Skeleton Crew collection (1985) or at Internet Archive. This short story was first published in a 1981 edition of The Twilight Zone Magazine.

*Junket is also an old-fashioned dessert which I haven’t eaten since my grandmother died. I was never a fan.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS FOR “THE JAUNT” BY STEPHEN KING

- All stories set in the future are really saying something about the present, so it pays not to dwell too much on whether futuristic stories are ‘realistic’ or not. Instead, what does Stephen King’s depiction of a futuristic teleport venue tell readers about the 20th century experience of airports? If this story were rewritten today, how would we imagine the future differently from how King imagined it ?

- Look up the meaning of heterotopia, as Michel Foucault described it. What can you say about heterotopies in relation to airport departure lounges, or to Stephen King’s teleport departure lounge experience?

- Of the Oates family, which of the family members is written by Stephen King to garner more sympathy?

- Consider how Stephen King has gendered the characters. Who has made all of the family decisions? What do you think of King’s depiction of Patricia, the viewpoint character’s daughter? How does this gendered characterisation compare with more modern science-fiction stories, e.g. the film Interstellar (2014)?

- In “The Jaunt”, a scientist invents teleportation by accident while trying to find a solution to a mundane problem. From real history, what would you consider the most significant accidental breakthrough in science for the advancement of humankind?

- After testing the invention on various animals, the first human guinea pig is a prisoner from Death Row. Discuss the ethics of consent behind utilising human prisoners for ground-breaking experiments. Is it more or less ethical to sacrifice another animal?

- What various writing techniques has Stephen King utilised to create the infamously shocking ending?

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE JAUNT” BY STEPHEN KING?

PERIOD

The year 2287, the year 1987 plus 300 years.

DAD GOT A NEW JOB, NOW WE’RE MOVING TO MARS

Stephen King utilises the familiar experience of catching a plane in an airport but these people aren’t catching an aeroplane — they are teleporting themselves to Whitehead City, Mars. So far, this is sounding very much like a Ray Bradbury plot. (The influence is strong and clear.)

Rather than ‘passengers’, people who utilise the technology of The Jaunte (as it was previously known) are called ‘Jaunters’.

THE OATES FAMILY

A nuclear family of four from Schenectady, New York, wait in the slightly ominous departure lounge. This is their first teleport as a family, though the father has done it about 25 times before. He’s being transferred for work.

This father, called Mark, is the viewpoint character. He has a wife called Marilys, an annoyingly depicted 9-year-old daughter called Patricia who Stephen King writes as ‘giggling shrilly’ for no good reason, and a 12-year-old son called Ricky. This trip is more than a holiday — the children will be attending school on Mars alongside the children of ‘engineering and oil-company brats’.

The creepy father mulls over his decision to take his young children on this experience to Mars and thinks about how his daughter will soon be developing breasts. (For comparison, he thinks about his son’s adolescence in a more generalised way.)

THE GRADUALLY REVEALED DYSTOPIA

Readers gradually get the idea that Earth has gone to wreck and ruin due to human greed and negligence. People (Americans) can’t heat their houses due to lack of oil; there’s very little potable water left.

If this story were written today, the author would more likely be writing about Americans’ inability to cool their homes rather than heat them.

Next we learn that humans have poisoned most of their drinking water, which is the main concern.

ARENA

By this point, humans have explored the Solar System and have colonised Mars and also managed to utilise resources on Venus. Humankind is looking to expand to other solar systems using ‘Jaunt-ships’.

THE DEPARTURE LOUNGE GETS MORE CREEPY

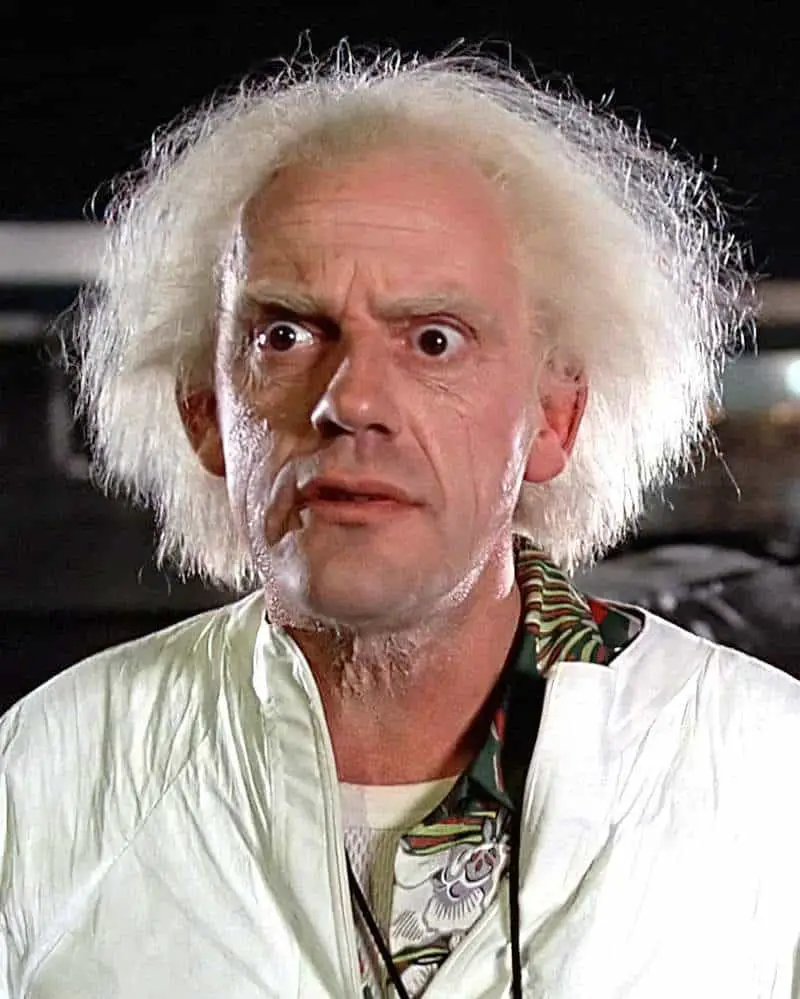

This teleporting venue of the distant future is very reminiscent of a modern airport, with an extra touch of the Kafkaesque. However, King tells us it’s ‘not at all grungy’:

It was wall-to-wall carpeted in oyster gray. The walls were an eggshell white and hung with pleasant nonrepresentational prints. A steady, soothing progression of colors met and swirled on the ceiling. There was one hundred couches in the large room, neatly spaced in rows of ten.

“The Jaunt” by Stephen King

The trouble with being too specific about interior décor in a sci-fi story: what seems modern now will be outdated in a decade. Think of your local thriving shopping mall and how often that’s been revamped.

Nonrepresentational art: Artwork which is not supposed to represent anything in the real world. This is different from abstract art, which refers to recognizable imagery that does not reflect actual appearance.

Airport staff hand out glasses of milk, suggesting infantilization. And what’s with the ‘child’s slide’ leading down to a ‘trough’?

At one side of the room was an entranceway, flanked by armed guards and another Jaunt attendant who was checking the validation papers of a latecomer, a harried-looking businessman with the New York World-Times folded under one arm. Directly opposite, the floor dropped away in a trough about five feet wide and perhaps ten feet long; it passed through a doorless opening and looked a bit like a child’s slide.

“The Jaunt” by Stephen King

Attendants walk quietly around the lounge with trolleys of creepy-looking medical equipment reminiscent of mid-century psychiatric hospitals and start knocking people out with masks, tubes and gas. Mark Oates’s creepy gaze settles on the briefly exposed varicose-veined thigh of a woman who has been knocked out. He is confident his son will deal with this process without making a fuss, but worries that his daughter will wig out.

THE HETEROTOPIES OF “THE JAUNT”

Let’s talk for a moment about the heterotopia of an airport departure lounge. Heterotopies are:

- both real and unreal

- have a specific operation anchored to a specific time

- have incompatible elements in a single state

- which function in temporal discontinuity

- are demarcated but acceptable, linked to the opening and closing of doors

- create some kind of illusion

The Oates family are in the Jaunt departure lounge for a specific reason (to be teleported to Mars). Only certain people are allowed to be there, and in fact there is a huge waiting list of people anxious to leave Earth. If someone chickens out, another person arrives to take their place. This is all carefully monitored by the opening and closing of some door. (And in this story, a memorable slide.) The restful décor works to create the illusion of calm and safety, when in fact this proves to be a dangerous procedure.

Heterotopies tend towards two extremes: Rare chaos and rare order. Stephen King utilises ‘order’ for the wrapper story and delves into chaos for the story-within-a-story as told by the father.

We could say that the science fiction concept of inhabitable hyperspace is the ultimate heterotopia (other place).

LEVEL OF CONFLICT: MIDDLE EAST As ENEMY

Readers learn simply that the world is running out of oil, which kicked off the whole Mars exploration in the first place. What oil remains is controlled by the Middle East ‘desert peoples’ who use it to wrest political control.

With that brief mention of ‘desert peoples’ controlling the last of Earth’s oil, we can deduce that the world is at war. For the Oates family, going to Mars isn’t the worst option.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY: teleportation

Stephen King gives just enough historical information about the teleportation technology to create verisimilitude for readers, which is a good choice, because it’s easier to explain away the history of a technology rather than how futuristic technology actually works.

The father’s explanation stops short because he doesn’t want to freak out his daughter, soon to have a mask on her face.

Something about particle transmission. This happens in a barn. The inventor is trying to invent technology for long-distance material shipping but accidentally invents something spectacular.

Accidental breakthroughs in science are surprisingly common. The most significant accidental breakthrough widely regarded to be penicillin.

Test subjects are mice. He teleports a couple of his own fingers across the barn before he works out how to do the whole body.

But then we get the story-within-a-story about a brilliant genius by the name of Victor Carune, and his amazing scientific breakthrough.

Anyway, the father knows all this because the inventor got an article published in Popular Mechanics Magazine before he was suppressed by the government.

Maybe if he directed his explanations at his daughter she might be less concerned, but Mr Oates has decided to explain the whole history of teleportation to his son instead. He doesn’t want to worry Patricia’s pretty little head. When she does ask a question, Mark tells her he doesn’t have time to ‘sketch the whole mess for you’.

BACK TO VICTOR CARUNE

To assuage the fears of his children (and also, by the way, infantilising his wife), Mark Oates continues the story of Genius Inventor Victor Carune, who manages to teleport a pencil, then his keys, then his watch. (Have you noticed how important wrist-watches are to Stephen King? They make it into a surprising number of his stories.)

When the watch makes it through the teleportation process, time to try it out on mice.

The kid demand to know what happened to the mice, but Mark does not want to make his wife ‘hysterical’ by telling the truth about those early experiments.

Victor’s original mouse isn’t too healthy. Stephen King affords the wife just a little agency by telling readers with a shift in point of view that she doesn’t buy the false smile Mark directs at his children by way of keeping them calm. The mouse dies. But the second mouse makes it.

Stephen King goes on and on about which mice died, which mice made it through, how Victor started experimenting with goldfish. All of this experimentation is happening without the approval of The Government. As noted at TV Tropes, King does a bunch of science hand-waving in this part of the story. He’s writing for plot, not for science enthusiasts here for the science:

TV Tropes

- In “The Jaunt”, Victor Carune tests the process on a pair of goldfish after the test mice all died or went catatonic. One fish dies, but the other somehow manages to shake off the effects after a few moments, which is implied to be because of it’s limited memory making simply forget about the time-dillation effect of The Jaunt. The idea that goldfish only retains a few seconds of memory at a time is a popular myth, but it doesn’t have any actual truth to it.

- Although it’s sure to cause a great deal of chaos, the tarantula Spike leaves for the McCarthys is in all likelihood not going to kill anyone, even if someone in the household gets bitten. Unless you’re allergic to their venom, the bite of a tarantula isn’t deadly, just very painful. Of course, there is the possibility Spike (and King) knows this, and really doesn’t care. He just wants to introduce a little anarchy to the McCarthys.

The first human test subject is a death row prisoner bound for the chair.

LONG STORY SHORT

Victor Carune works out that teleportation of animals only works if the animals are put to sleep.

The great man died before his genius could be recognised. Not only was he genius enough to invent the technology, but he also saw how humans were going to use it — for space travel and for mining on other planets.

THE TERRIBLE 1990S

In Stephen King’s 1981 story, the 1990s are a decade of dystopia. Looking back, though, the 1990s was a remarkably stable decade (for most of the world, at least). I was a teenager during the 1990s and can honestly say I did not spend any time at all worrying about climate disasters or world wars. When CFCs were banned in 1996, it felt back then like we could trust political leaders to get things under control, even if they were a little slow off the mark.

Only looking back in hindsight do we understand that the 1990s appeared stable but provided the set-up for all sorts of future trouble.

2045

A century on from WW2, Stephen King’s imagined future involves water-prospecting, and history revisits 1906 with regards to oil.

STEPHEN KING’S NARRATION: A BALANCE OF SUMMARY AND DIALOGUE

As the father continues to tell the story, he uses language (e.g. swearing) no 1980s father would use with their children. Stephen King summarises for readers the story Mark Oates tells his wife and children.

PACING HALTS to a pause

Readers now hear the gory parts Mark avoids telling his story. Whenever writers tell us what doesn’t happen, this is the pacing slowing down to a ‘Pause’.

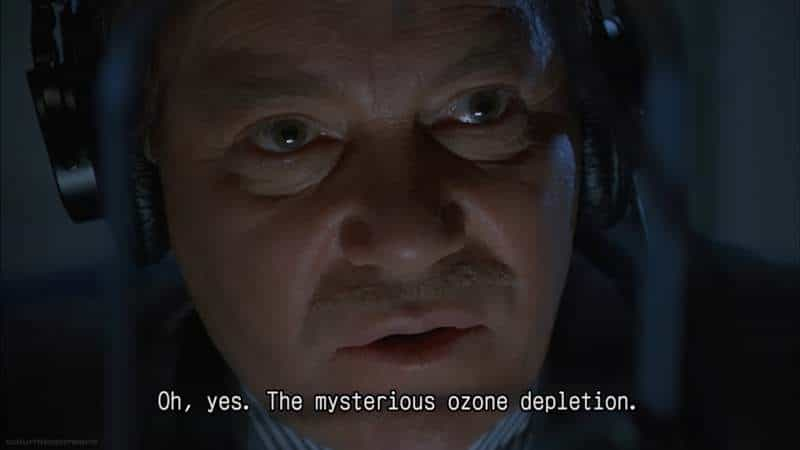

Because the technology kills people who aren’t put to sleep, it is now used as a murder weapon. A researcher kills his wife in this way, by pushing her out into ‘the ozone’. (People talked a lot more about ‘the ozone’ back in the early 1980s when the world was coming to grips with the damage wreaked by CFCs.)

But the male researcher gets off the murder charge because no one can prove his wife is really dead. This isn’t a bad allegory for the way men have long abused the legal system by pleading all sorts of bullcrap about why they momentarily lost control and were somehow driven to it by their victim.

Hoist by His Own Petard: In “The Jaunt”, the story of a man who shoved his adulterous wife into an open teleport with no exit is brought up. It’s mentioned that, at the man’s trial for murder, his lawyer attempted to make the case that his client wasn’t guilty of murder because his wife was technically still alive. Unfortunately for him and his client, the jury only have to briefly consider the absolutely horrific implications of that defence before finding the man guilty and sentencing him to death.

TV Tropes

AUTO-CANNIBALISM

Now we’re heading towards the end of the story, Stephen King offers up food for thought, regarding the big ideas of the story:

Mark fell silent, troubled by his son’s eyes, which were suddenly so sharp and curious. He understands but he doesn’t understand, Mark thought. Your mind can be your best friend; it can keep you amused even when there’s nothing to read, nothing to do. But it can turn on you when it’s left with no input for too long. It can turn on you, which means that it turns on itself, savages itself, perhaps consumes itself in an unthinkable act of auto-cannibalism.

“The Jaunt” by Stephen King

Mark Oates is talking about the human mind, but the story is also about how humans have ‘cannibalised’ the Earth, to the point that it is no longer inhabitable.

a gap in the narrative

Back to ‘talking about story pacing’, Mark wakes up and he’s on Mars. A ‘narrative gap’ perfectly emulates the feeling of waking up from anaesthesia. If you’ve ever been medically sedated, it’s surprising to wake up and feel like no time has passed at all. This is most unlike sleep, in which we awaken with some sense of how long we’ve been sleeping.

THE SHOCKING ENDING

Mark Oates has underestimated his son. By telling him that story, leaving some of it out, his daring, curious boy has held his breath for the anesthesia. He wanted to see what happens during the teleporting process.

When the family reunites on Mars under a dark sky and a dome, the son inhabits a boy’s body but is an elderly man. He is yelling. Even staff who were trained for all eventualities, scatter. His mother is a screaming mess.

In one of Stephen King’s most gruesome endings, 12-year-old Ricky claws out his own eyes. He’s gone mad after spending so long inside the Jaunt, and after having seen what he has seen.

This is a classic cosmic horror ending. Cosmic horror ends in madness, death or both.

RESONANCE

That final scene hits hard not for the gore, but because of the humanity. Members of a family have aged at different rates. The son will die soon. This goes against the natural order of things. We also feel massive regret at all that time lost together. It’s as if Ricky has died even while still alive. A shocking prospect.

The best thing about stories which utilise this time-travel-ageing trope and similar is that it is physically possible, according to what astrophysicists understand about time. There’s no more visceral way to communicate the complexities and terror of time passing to an Earthbound audience than to illuminate it via a family, because we all understand that time is terrible. We age, we die. We try not to think about it too much.

THE INFAMOUS ENDING

Although Steven King has no time for evangelical Christianity (cf. “Children of the Corn”, King’s stories draw from ideas in common with stories in the Bible. In this case, the son has seen something glorious while in the nowhere-world between life and death:

Narratives of enchantment emphasize the blindness of the victim to the human world when she [the fairytale victim is usually a ‘she’] is incorporated in the supranormal sphere. A similar trope of blindness recurs in descriptions of the relationship between the human world and the afterlife. It is only after death that man can see eternity with clarity: human life is thus a haze that prevents him from perceiving the realm of God.

A legend from Korsholm parish seems to rely directly on the idea that one sees clearly at the time of death:

If one takes soul water from the eyes of a dead man, at the moment of death, and smears it onto one’s eyes, then a haze falls from one’s eyes, and one starts seeing all that will befall one in this life and in the afterlife, and one will become a mediator between the dead and their relatives, so that the dead come to [such a person] if they have something to say to the living, and one has the power to call forth the dead as one wishes.

But an impious [person] should not do that. There was a man, who was a great drinker, and his wife heard about this, and she thought that if his eyes were opened, he would stop drinking, and that’s why she gave him these drops to drink, and his eyes were opened and he saw how he would fare in eternity, and therefore he was afraid of everything and [it] ended with him drowning himself.

Soul water, taken from a dying person at the moment of death, bestows the ability to see what happens in the afterlife because it is at this precise juncture that the blindness of the human world gives way to the vision of eternity. In this instance this trick is presented as a rather bad idea, but it does point to a way in which the limitations of human existence may be overcome. Thus … normal sight takes place through a haze, blocking the view of things beyond.

This motif is also present in the Bible, where the vision of human life is described as seeing “through a glass, darkly” (1 Corinthians 13:12), and when man beholds the glory of the Lord, it is “as in a glass” (2 Corinthians 3:18). Man must escape his spatial and temporal environment (the chronotope of the human world) to fully actualize the cornerstone of his identity, his identity as a Christian and redeemed creature.

Ingemark, Camilla Asplund. “The Chronotope of Enchantment.” Journal of Folklore Research, vol. 43, no. 1, 2006, pp. 1–30. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3814858. Accessed 10 Nov. 2023.

Aside from the terror of time passing, the ending of “The Jaunt” shocks because of the story-within-a-story technique. The wrapper story (of the Oates family in the departure lounge) has been written in realistic style. The departure lounge of the Jaunt is basically an airline departure lounge, and the historical story contains so much detail it runs to the boring. (At least, that’s the effect it has on me.) The dad’s story about Victor Carune lulls me into a sort of bored trance.

All of the gory stuff in the middle of this tale — which may have otherwise prepared readers for a shock ending — happens only in the historical story-within-a-story as recounted by the dad. Basically, Stephen King gives readers no warning*.

*Some people would use the word foreshadowing. To my mind, it’s not foreshadowing unless it works at a metaphorical level.