A handful of children’s authors of the late nineteeth to early twentieth centuries were experiementing with innovative forms of story with radical content: Oscar Wilde, P.L. Travers, J.M. Barrie, Astrid Lindgren, John Masefield and E. Nesbit. These storytellers were pushing the boundaries of what people considered acceptable for children, and we have them partly to thank for the wonderful children’s literature we see on the shelves today.

Nesbit was especially influential. Even if you’ve never read any of Edith Nesbit’s actual books, you’ve read books in the Nesbit tradition — basically all modern children’s literature. That’s how influential she was.

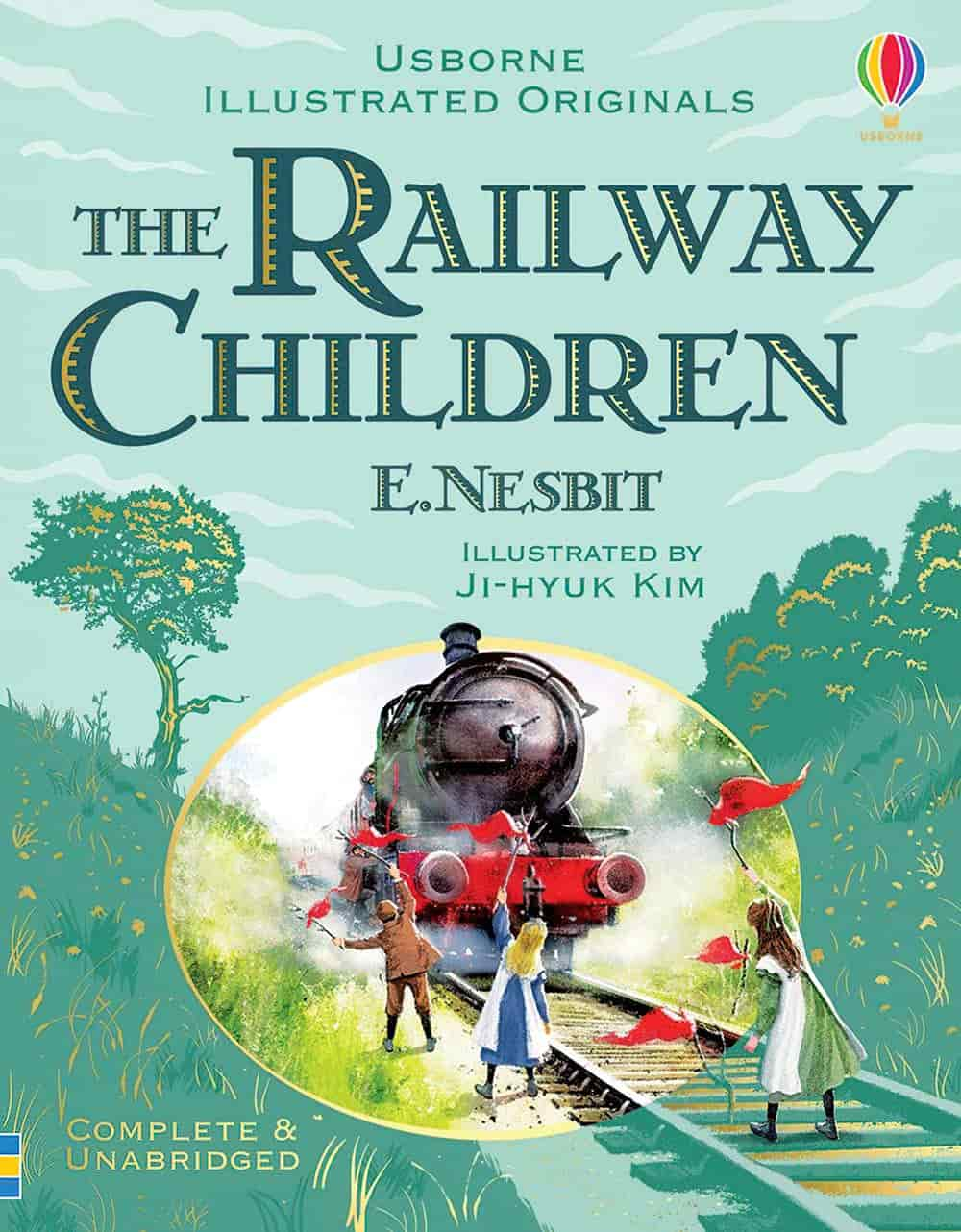

Edith Nesbit (married name Edith Bland; 15 August 1858 – 4 May 1924) was an English author and poet; she published her books for children under the name of E. Nesbit.

Wikipedia

E. Nesbit belonged firmly to the writers of the First Golden Age of Children’s Literature, marked by its stories about children who acted rather than thought. These were resourceful and resilient children, and they were proud of their class. They were patriotic. Children are wiser than adults in many respects. Nesbit was one of the first to create this dynamic (e.g. Story of the Amulet), which would not have been possible without the ‘romantic reevaluation of childhood‘.

BASIC BIOGRAPHY

Edith grew up with a mother who had been widowed in a part of Surrey which is now Greater London. Accordingly, Edith thinks that bringing children up in London is awful. She much prefers the freedom of the country for children.

At the age of 21 she had a shotgun wedding but her new husband’s business partner made off with all their money. This is why she took up writing and painting greeting cards. Her husband became a writer too, but Edith was the main breadwinner.

She was a bit of a Bohemian Dorothy Parker type. She smoked long before it was acceptable for women to do so. (This gave her bronchial problems and was eventually the death of her.) She bobbed her hair when women were meant to wear it long.

The economic realities of the time: families were often in trouble, as was hers. Nesbit wrote numerous times about families who were struggling with money. The father is ill or redundant or defrauded by a business partner or even in prison. The mother might be ill, or caring for a sick relative. The children often have to go and stay with unsympathetic strangers in horrible lodgings. Even when Edith keeps her fictional families together, it’s usually in slightly impoverished surroundings.

Socialism

An important thing to know about E. Nesbit is that she co-founded the Fabian Society, which is now affiliated with The British Labour Party. So, E. Nesbit was very socialist. This of course comes across in her work. Her books recommend socialist solutions to problems. In the typical Victorian fairy tale class lines are sharply drawn. Aristocratic children are thought to be morally and intellectually and generally superior to everyone else. Most of Nesbit’s characters are middle class but every now and then she wrote a character like Mabel (The Enchanted Castle) from a lower economic rung. Dickie from Harding’s Luck is basically uneducated but is shown to be very smart, imaginative and courageous. The aristocratic child is mean, cowardly and pretty stupid. This is a common trope today — smart underdogs versus stupid rich kids, but Edith Nesbit started it.

Another common trope of the Victorian era: A rich child befriends a poor one and improves them. In The Mixed Mine Edith inverted it — the poor child improves the life of the rich one.

Serialisation

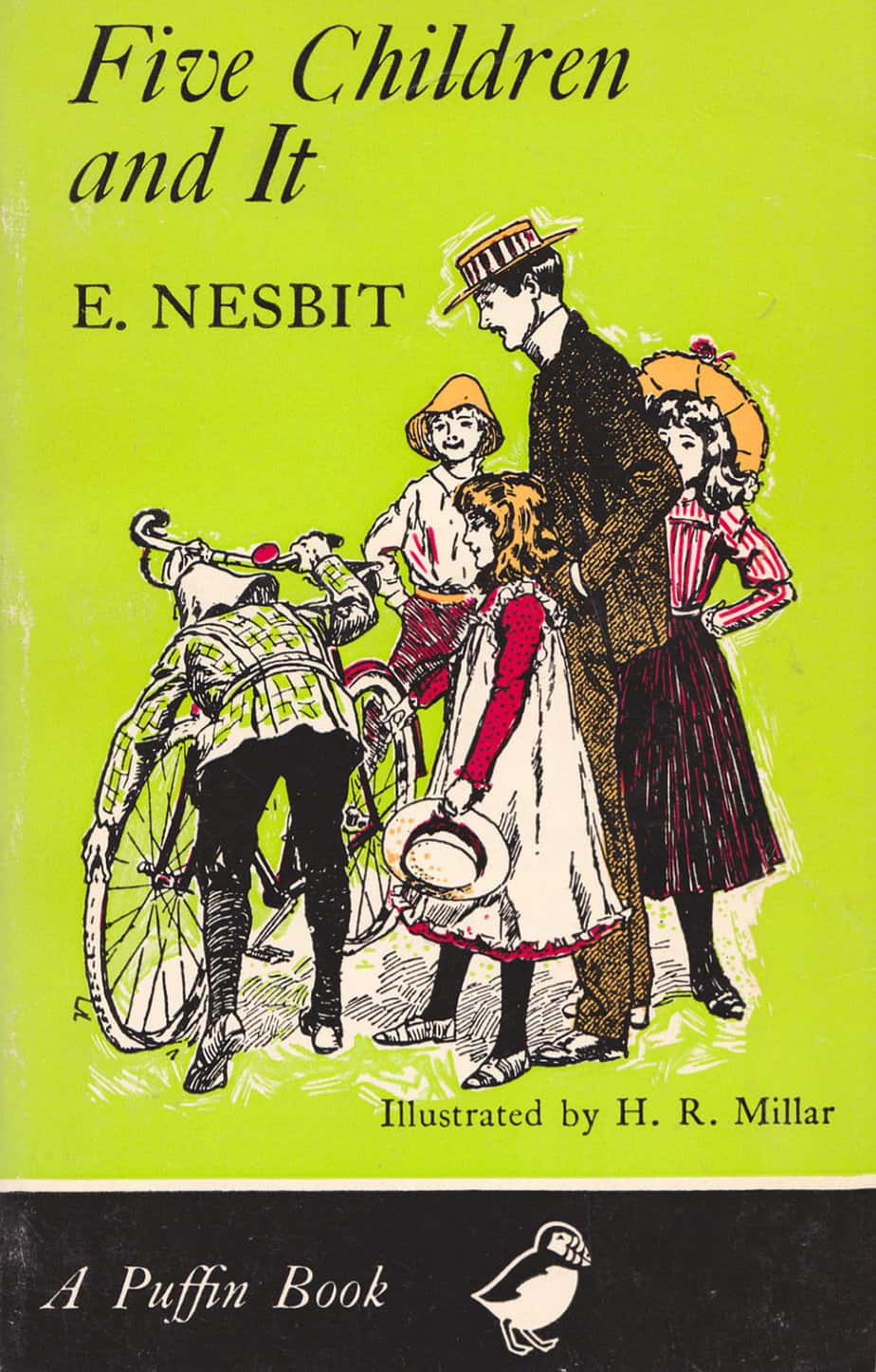

Many of her books suffer from having been written in serial stories. With Five Children And It, for example, the book is divided into the granting of wishes. Each chapter had to have a self-contained plot and climax, which is not ideal.

Only Children

Nesbit didn’t really ‘get’ only children. She herself had a sister, a half sister and 3 brothers. The closest she got to an only child in fiction was Mabel of The Enchanted Castle.

Nesbit and her husband had an open marriage, though it was mostly the husband who slept with other people. Edith ended up taking in two of his illegitimate children and raising them alongside her own three. (Busy as she must have been, she formed a few romantic attachments of her own, the most famous with George Bernard Shaw. But that was just close friendship.)

MAGIC

Magic is used both as a comic device as well as a serious metaphor for the power of the imagination.

She loved to write about saurian monsters (monsters that look like big lizards). She usually called them megatheriums.

NESBIT’S INFLUENCE ON NARRATION

Nesbit’s voice seems unremarkable to contemporary readers because we see it everywhere. But at the time it was highly unusual. Nesbit spoke to children as if she were one of them, when everyone else was form, leisurely and didactic. Nesbit’s voice is inform, direct and that of a sensible child coolly commenting on the world. She adopts the child’s point of view whole-heartedly.

E. Nesbit introduced the technique of Paralepsis as Secondary Narrative into children’s literature.

NESBIT GOT ADULTS OUT OF THE WAY

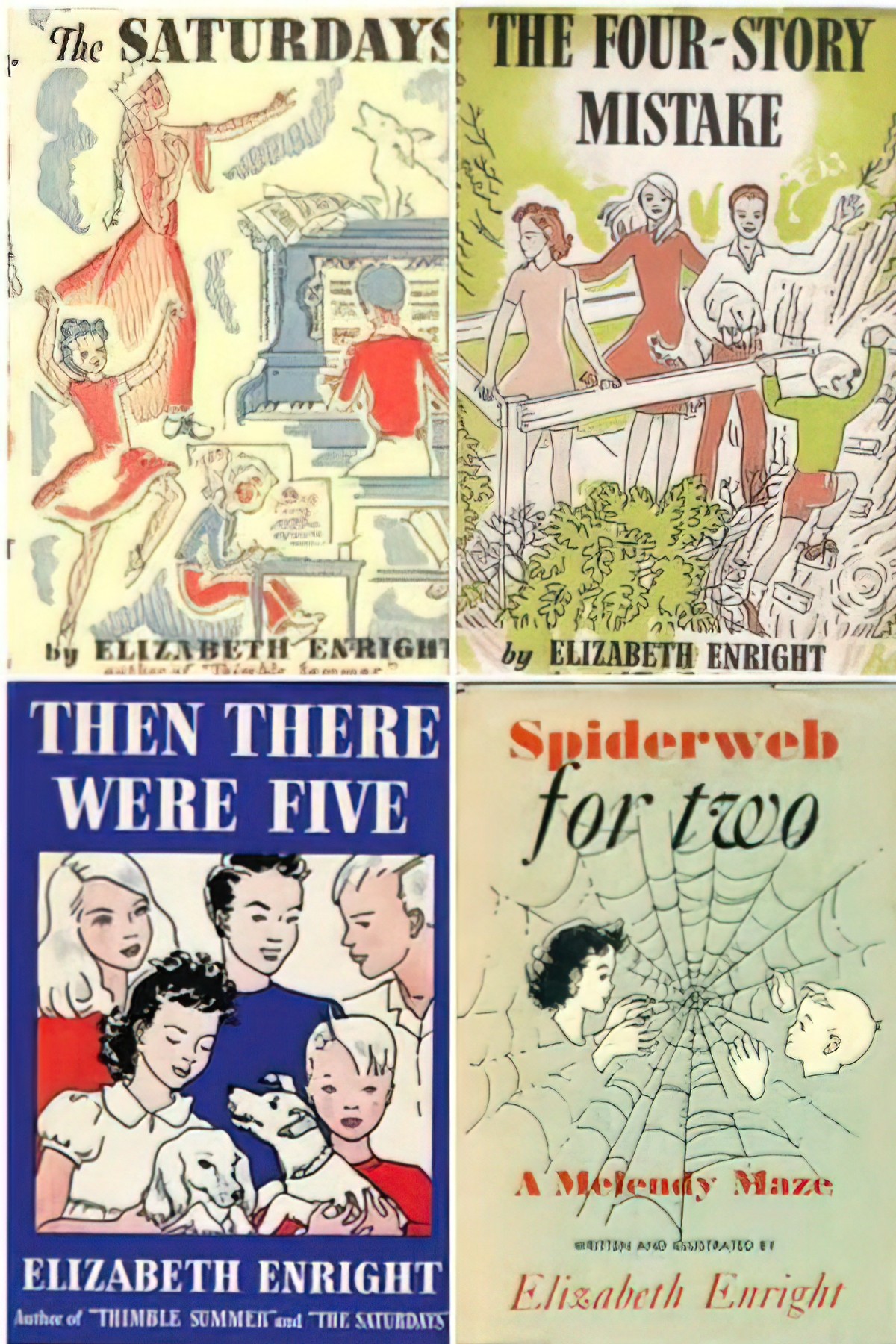

Nesbit wrote some magical stories and some realistic ones. In her non-magical stories — The Bastable series — she removes one parent (prison/death/faraway country) and interposes a surrogate (housekeeper/Great Southern Railway Company) between the children and the remaining parent. This surrogate can now be upset without emotional repercussions. The Bastable series has influenced all those books that have come since, in which children have autonomous adventures: e.g. Swallows and Amazons, and the Melendy series: The Saturdays, The Four-Story Mistake, Then There Were Five, and Spiderweb for Two. by Elizabeth Enright.

NESBIT’S INFLUENCE ON MODERN POPULAR AUTHORS

Nesbit has been hugely influential on authors from the Second Golden Age of children’s literature:

E Nesbit has perhaps been strongest of all. Her stories, whether magical or not, are firmly rooted in the real world and have been hugely influential on books of the Second Golden Age which people of my own generation loved – Philippa Pearce’s Tom’s Midnight Garden, Diana Wynne-Jones’s Chrestomanci books, Lucy M Boston’s Green Knowe quartet, Peter Dickinson’s Changes trilogy, John Masefield’s The Midnight Folk, Joan Aiken’s Wolves of WIllighby Chase sequence and Eva Ibbotson’s hilarious witches and ghosts. Her dauntless brothers and sisters were echoed by Enid Blyton, Arthur Ransome, Noel Streatfeild and, more recently, a constellation of contemporary authors like Hilary McKay, Anne Fine, Fiona Dunbar, Cathy Cassidy, Anthony McGowan, Frank Cottrell Boyce, and Francesca Simon. Above all, she is acknowledged as the single greatest influence on Rowling, presumably because her conception of how the logical consequences of mixing the magical with the mundane is so comical. All have drawn from her faultless ear for family drama, her abundant sense of humour and her social conscience.

Amanda Craig

The works of Edith Nesbit aren’t perfect as works of art. The work Nesbit produced between the age of 20 and 40 is conventional and sentimental (by modern tastes). This all changed with The Story of the Treasure Seekers, about six London children who try to restore the family fortunes. In her character Oswald Bastable, it seems Edith was finally able to unleash the childhood version of herself.

Nesbit had an influence on another well-known children’s writer, C.S. Lewis:

The author’s voice in the Narnia’s books kindly explained things to the child reading…It was a gorgeously certain voice, which in itself lent a wonderful solidity to Narnia’s stars and sausages, so that they blazed in their spheres and swelled in their skins, but it never spoke from a position of adult detachment…He used the trick of uncondescending explanation, borrowed from E. Nesbit, only to involve you in perceptions you couldn’t have had on your own. Which made it doubly frustrating when the book was over, and you couldn’t invent any more of what you had taken part in.

Francis Spufford, The Child That Books Built

J.K. Rowling counts the books of E. Nesbit of some of her own childhood favourites:

I love E Nesbit—I think she is great and I identify with the way that she writes. Her children are very real children and she was quite a groundbreaker in her day.

Echoed here by Amanda Craig:

E Nesbit has perhaps given us the strongest DNA of all. Her stories, whether magical or not, are firmly rooted in the real world and have been hugely influential on books of the Second Golden Age – Diana Wynne Jones’s Chrestomanci books, Lucy M Boston’s Green Knowe series, Joan Aiken’s Wolves of Willoughby Chase sequence and Eva Ibbotson’s hilarious witches and ghosts. Her quarrelsome, highly believable brothers and sisters were echoed by Enid Blyton, Arthur Ransome, Noel Streatfeild, Roald Dahl and, more recently, a constellation of contemporary authors like Hilary McKay, Anne Fine, Cathy Cassidy, Frank Cottrell Boyce, and Francesca Simon. Above all, she is acknowledged as the single greatest influence on JK Rowling, presumably because her conception of mixing the magical with the mundane is sharply satirical. The most recent winner of the Costa Prize for Children’s fiction, Kate Saunders, updated one of Nesbit’s most famous books with Five Children on the Western Front – having cleverly worked out that, in just a few years, her famous Edwardian family would have been embroiled in the First World War.

And so does Philip Pullman:

The books I read as a child shaped my deepest beliefs. When I was at university, my friends and I were thrilled to discover that our childhood favourites seemed even more powerful than we remembered. This was true of classic authors such as George MacDonald, Rudyard Kipling, E Nesbit and Tove Jansson; or 1960s writers like Alan Garner, Susan Cooper, Peter Dickinson and Ursula Le Guin.

NESBIT’S REVOLUTIONARY TREATMENT OF ANIMALS

Margaret Blount in Animal Land writes that a little known (now) but influential story about mice was hugely influential (and probably forms the template of Peter Rabbit). See my post Rodents In Children’s Literature for more about that.

However, it wasn’t until Nesbit came along that readers saw ‘real human souls in human bodies. Until that point, stories about animals had been about humans whose appearance has been changed by magic. Prevailing religious views would not have made such stories possible until Nesbit’s generation of writers came along.

Edith Nesbit’s The Cathood of Maurice was groundbreaking in this regard. It is the first short story in a collection of twelve, published in the anthology called The Magic World.

Another two stories of this tradition were The Sword in the Stone by T. H. White and Jennie by Paul Gallico.

NESBIT AND TIME TRAVEL

In The Story Of The Amulet, Nesbit basically invented a new subgenre of the time travel story. That way of thinking about time travel can be seen in stories from Sherman and Peabody to Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure. For more on that, listen to the Long Now: Seminars About Long-term thinking delivered 5 June 2017 by James Gleick.

Published in 1906, the very concept of time travel was very new at that time. In The Time Machine, H.G. Wells has to go to great lengths to explain the fourth dimension to the friends who have gathered in his drawing room. The modern reader may wonder why. That’s because the term ‘time travel’ was not familiar to anyone, and people learned in school that there were three dimensions. Einstein came along quite soon after and proved that time really is the fourth dimension. (In case you’re wondering, H.G. Wells didn’t have any special insight into astrophysics — the fact that he’d written fiction about what later turned out to be dead accurate is more of a commentary on ‘ideas that were in the air’ around the turn of the century.)

In any case, Nesbit had her finger on the pulse. Without the Internet, how did Edith Nesbit have access to these ideas? There can only be one answer: She was immersed in an interesting subculture of people and was having in depth conversations. Nesbit was a member of this intriguing organisation. She was no doubt also well-read. She had a special interest in ancient civilisations in general and in ancient Egypt in particular.

C.S. Lewis seemed to borrow the time travel ideas of Nesbit and used them in The Horse and His Boy (1954) and The Magician’s Nephew (1955). C.S. Lewis knew Nesbit’s work well and happily borrowed from her tone, her devices, and her effects.

As I read E. Nesbit’s The Story of the Amulet, a tale of children’s magical adventures, a feeling of familiarity came over me. This 1906 book seemed to anticipate C. S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew, published almost exactly half a century later (1955) but, unlike the rest of the Narnia series, set back in the era when Nesbit herself was writing. It’s well known that Nesbit influenced Lewis’s Narnia series – he acknowledged it himself. His template – a group of sibling children having magical adventures – was inspired by Nesbit’s books, and scholars have identified various specific instances in the Narnia books that Lewis adapted from different Nesbit stories.

The Toronto Review Of Books

If you’re a socialist rather than a Christian and you enjoy the Narnia stories you might consider going back to read Nesbit.

NESBIT AND GENDER

E. Nesbit, Enid Blyton and Arthur Ransome wrote for both boys and girls in an era when books were gender bifurcated — domestic stories for girls; adventure stories for boys. They did this by including both boys and girls going off on adventures. There were no adventure stories for girls starring only girls. In Blyton and Ransome’s books, the males are generally more active, making the plans and decisions.

Nesbit was an early feminist (though didn’t necessarily use that term). At the time her girls were highly subversive. They are brave and adventurous, just like their brothers. They never sit round waiting for someone to rescue them.

“Father, darling, couldn’t we tie up one of the silly little princes for the dragon…? I fence much better than any of the princes we know.”

a girl’s dialogue from The Last Of The Dragons, more reminiscent of Pixar’s Brave than of anything else from that era.

As a child Nesbit would have been described as a ‘tomboy’. She declared that she never loved a doll in her life, she loved playing pirates with her big brothers during the holidays and was generally rebellious, both at school and at home.

Nesbit’s Phoenix is referred to as “It”, and is not described in terms of gender. The female children, Anthea and Jane, enjoy a range of activities, and do not appear to be limited by societal restrictions related to gender. Prior to these stories girls were treated to a whole lot of domestic dramas, whose main purpose was to persuade girls that being at home was fulfilling and the place to be.

Listen to The Railway Children at Librivox for Free