Good children work hard.

Lazy children lose out.

Working hard has an apotropaic effect on your fate. (So long as you keep working, bad things won’t happen to you.)

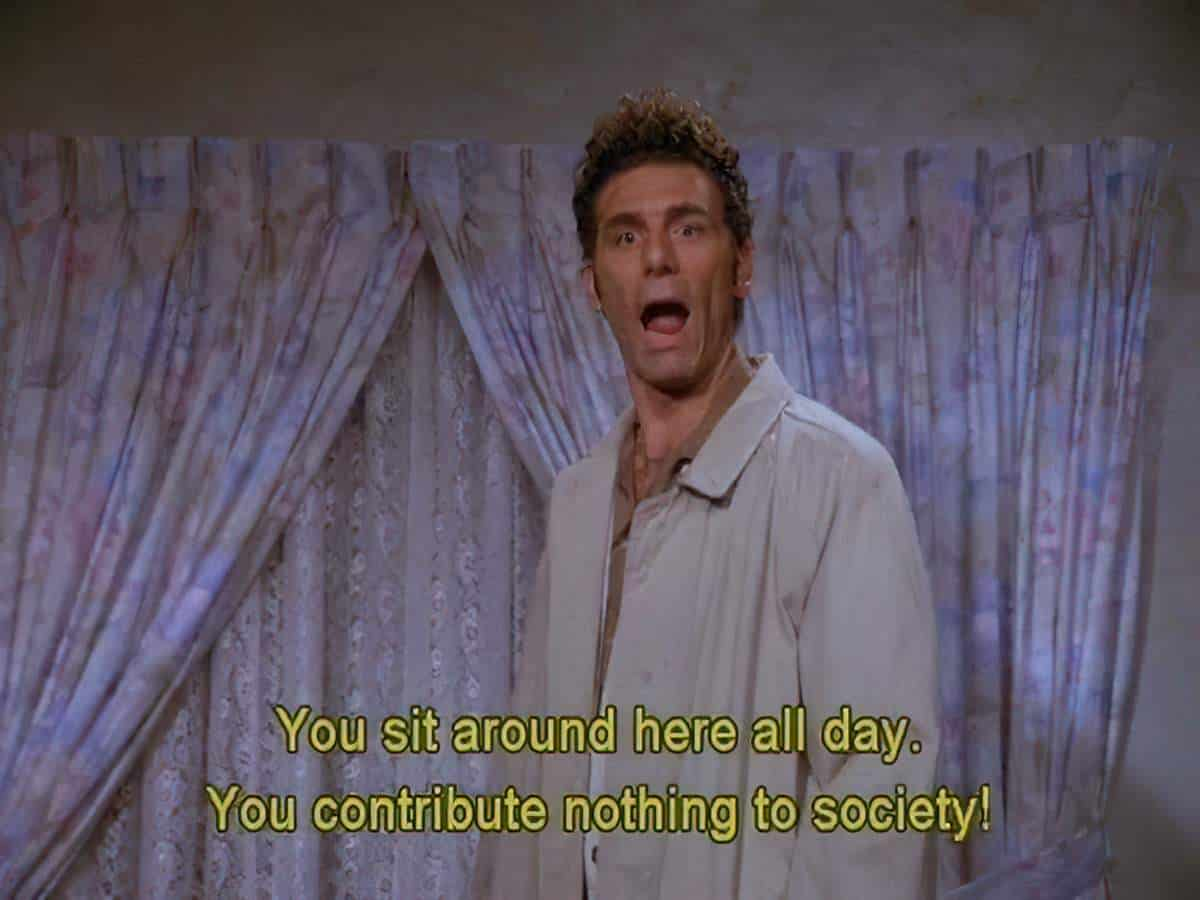

Tyler Durden was wrong, you are your job.

Career Advice

This view of work ethic is so ingrained throughout children’s stories that it’s hardly noticed. However, there is speculation these days (in fact since the 1970s) that humanity may be facing a post-work future. Some argue that no human job is ‘safe’ from robots and apps — the caring and creative professions will be last to go, but go they will.

What if our children, or our children’s grandchildren, are born into a world where most of them never work because robots — or a robot spin-off, yet to be invented — are the new slaves? The Romans and the Greeks managed to contribute so much to the world only because their slavery system allowed a well-educated gentry to dedicate themselves to art and ideas.

What if everyone was in that position? Our children’s grandchildren may look back on literature of the modern era — the literature our children are reading right now — and the work ethic may well stick out as an outdated feature of our age.

Some of our oldest stories are popular in part because of their strong work ethic. While Robinson Crusoe (and all of its descendants) is set on an island and is therefore partly escapist, characters don’t actually get to escape work. It’s hard work actually, living on an island. No matter the setting, we love characters who work. If they are lazy, or somehow manage to avoid work through sheer cunning (or even through pragmatism), we generally don’t want to see them get what they want.

Visible Work in Picture Books

I theorise that this is simply because certain jobs are easier to draw, but manual labour gets more space in children’s literature than mental work.

Examples Of Strong Work Ethic In Children’s Literature

The Little Red Hen

This is still a popular tale and conveys the clear message that if you want to enjoy something you must work to produce it. You may not jump in at the last minute to enjoy the fruits of someone else’s labour. In Robinson Crusoe, too, Crusoe takes great pleasure in baking his own bread.

The Faraway Tree by Enid Blyton

Blyton’s children were afforded plenty of time to explore the low fantasy worlds right under the adults’ noses, or even to solve crime, but Blyton made sure young readers knew they weren’t off in the woods picnicking until after their household tasks had been completed.

Northern Lights by Philip Pullman

At Mrs Coulter’s house Lyra is mostly decorative and although she is surrounded by beautiful, feminine things and dressed up like a doll, she has no sense of fulfilment until she runs away and is taken in by the gyptian boat people who give her plenty of chores to keep her occupied:

Now that Lyra had a task in mind, she felt all very well, but Pantalaimon was right: she wasn’t really doing any work there, she was just a pretty pet. On the gyptian boat, there was real work to do, and Ma Costa made sure she did it. She cleaned and swept, she peeled potatoes and made tea, she greased the propellor-shaft bearings, she kept the weed-trap clear over the propellor, she washed dishes, she opened lock gates, she tied the boat up at mooring-posts, and within a couple of day she was as much at home with this new life as if she’d been born gyptian.

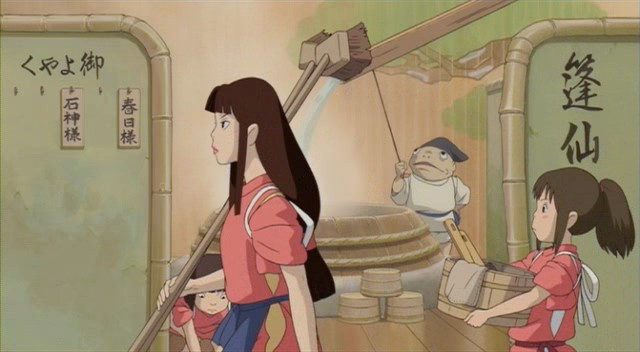

Spirited Away

This is an anime for children created by Hayao Miyazaki of the Studio Ghibli studio. Japanese culture is well-known for promoting a strong work ethic, linking work closely to a sense of self. In Spirited Away Chihiro has her name taken away — it is shortened to ‘Sen’. In order to get her full name back (her sense of self), as well as rescue her parents, she must go to work in the fantasy realm. Through pure hard work she somehow saves the day.

Hayao Miyazaki himself was notorious for his strong work ethic and he prioritised work over family, not atypically for a Japanese man of his age. He seems to have retired now, though came back from supposed retirement at least once. Oh, and now he’s back again.

Tar Baby

“The most perplexing aspect of this folk tale is that in many variants the rabbit is portrayed as a free-rider. Asked to help dig a community well, he says he prefers to live off the dew on the grass – and then proceeds to steal water from the well. Asked to till the soil, he refuses, but then proceeds to steal a cabbage here and a turnip there. If the rabbit represents the underdog, how is he also, to use Wagner’s phrase, “a selfish hustler”? Even more curiously, why is he so likeable?”

NPR

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

To do something well you have to like it. That idea is not exactly novel. We’ve got it down to four words: “Do what you love.” But it’s not enough just to tell people that. Doing what you love is complicated.

The very idea is foreign to what most of us learn as kids. When I was a kid, it seemed as if work and fun were opposites by definition. Life had two states: some of the time adults were making you do things, and that was called work; the rest of the time you could do what you wanted, and that was called playing. Occasionally the things adults made you do were fun, just as, occasionally, playing wasn’t — for example, if you fell and hurt yourself. But except for these few anomalous cases, work was pretty much defined as not-fun.

And it did not seem to be an accident. School, it was implied, was tedious because it was preparation for grownup work.

The world then was divided into two groups, grownups and kids. Grownups, like some kind of cursed race, had to work. Kids didn’t, but they did have to go to school, which was a dilute version of work meant to prepare us for the real thing. Much as we disliked school, the grownups all agreed that grownup work was worse, and that we had it easy.

Teachers in particular all seemed to believe implicitly that work was not fun. Which is not surprising: work wasn’t fun for most of them. Why did we have to memorize state capitals instead of playing dodgeball? For the same reason they had to watch over a bunch of kids instead of lying on a beach. You couldn’t just do what you wanted.

How To Do What You Love, an article from 2006 by Paul Graham