Fat studies scholars and activists have traced and challenged the longstanding association between fatness and ugliness. While fat bodies were once revered because they signified wealth and prosperity, the proliferation of advertising and consumer culture has, over the past four decades, turned a fat body into an ugly body. Such scholarship makes clear that the association of fatness with ugliness is not natural but instead emerges from the “historical and cultural positioning” of fat people in a society that benefits from their marginalization as well as from processes of adhering meaning onto bodies. The association between fatness and ugliness impacts fat people’s social and professional lives as well as their access to non-discriminatory medical and health care. Saguy and Ward argue that to “come out” as fat is to reject the association between fatness and ugliness (among other unjust associations); however, they recognize that such a move generates a climate in which some stigmas are reclaimable while others are not. Interestingly, they wonder when people might subsequently reclaim the stigma of “ugliness” by “coming out” as ugly.

On The Politics of Ugliness (Introduction)

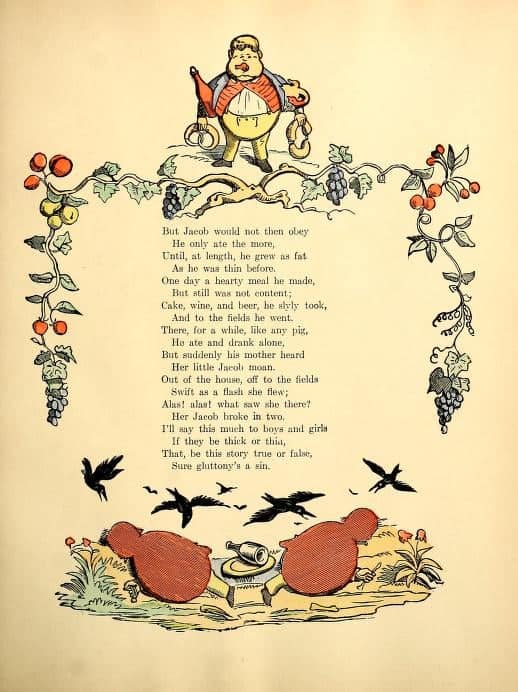

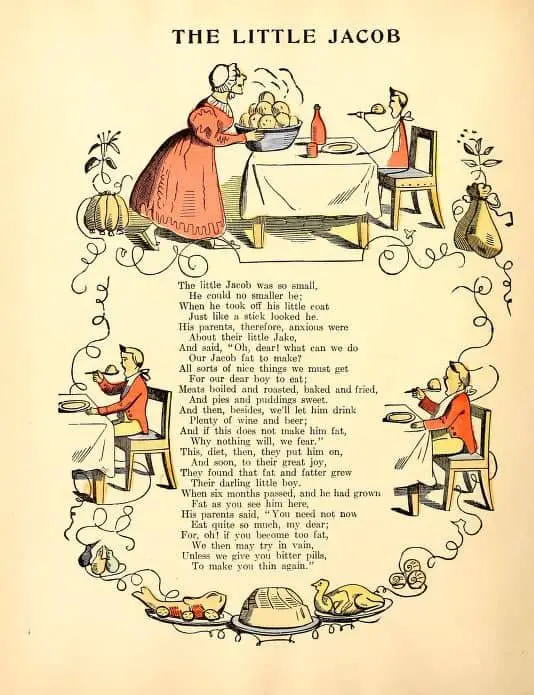

Children’s literature has been policing the body size of children since children’s literature began. If children are not too thin, they are too fat, sometimes in the very same cautionary tale:

Here’s a list of all the times I have felt like a fat female character was depicted + portrayed accurately in three decades of watching:

HAIRSPRAY

Kate Hagen

MY MAD FAT DIARY

YOU’RE THE WORST

SHRILL …this show is A LOT for me, pals!!!

FATPHOBIA AND THE DEPICTION OF FAT KIDS AS BULLIES

A fat bully character in a book implies that fatness is connected to bullying—because our culture already has that stereotype entrenched. A fat bully character in an individual book invokes the culture in which it exists, and brings all that to bear. Can’t help but.

diceytillerman

FATNESS AS CODE FOR GREEDY AND LAZY AND MORALLY CORRUPT

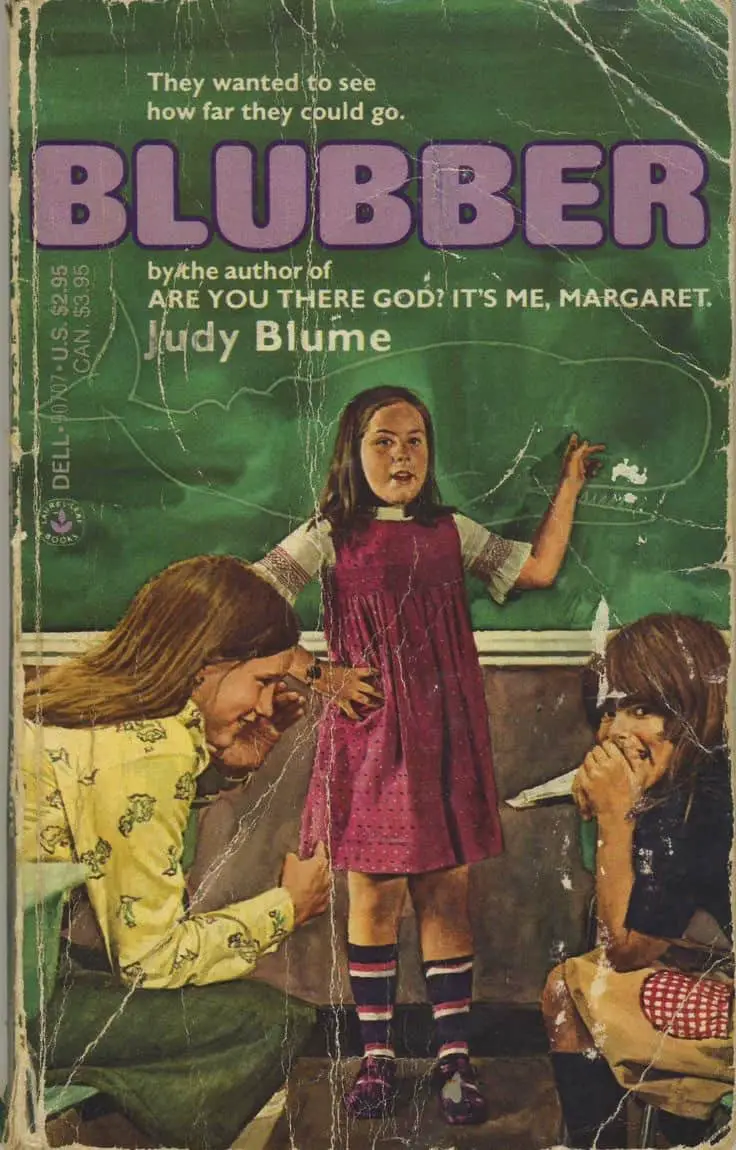

Rebecca Rabinowitz recently wrote a wonderful piece called, “Who’s that Fat Kid? Fat Politics and Children’s Literature” for the Children’s Book Council Diversity Blog. In it, she critiques the stereotypes and tropes of fat children in children’s literature: as either bully (ie. Dudley, Crabbe and Goyle in the Harry Potter Books) or a victim of bullying (ie. Judy Blume’s classic Blubber). Fatness often becomes code in children’s literature for gluttony, greed or other moral failings — just consider Augustus Gloop from Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory; the Oompa-Loompa song says it all: “Augustus Gloop! Augustus Gloop! The great big greedy nincompoop! Augustus Gloop! So Big and Vile! So greedy, foul, and infantile.”

From the Mixed Up Files

Dudley, Vernon, Umbridge, Crabbe and Goyle, Pansy Parkinson…Umbridge is described as having a horrible wobbling jowly chin and being shaped like a toad, the one time Pansy gets any physical description she’s “chunky”.Fred and George weren’t fat and weren’t cast as such in the movies (whereas people very much noticed how much more attractive the movie versions of Umbridge and Pansy were than their book descriptions).

Arthur Chu, 8:57 AM · Aug 1, 2021

FATPHOBIA AND CONCERN TROLLING ABOUT HEALTH

Putting Makeup on the Fat Boy by Bil Wright is one example.

FATPHOBIA AND GENDER

Here’s a question for writers: How are you introducing your characters? Do you introduce female characters differently from how you introduce male characters?

Here’s an example from a New Zealand author from the 1980s and 90s — one of the main authors studied in schools during that era. It’s from My Summer of The Lions by William Taylor. Our 13-year-old male protagonist meets his Samoan friend’s parents. First, the mother:

Mrs Tulisi sailed towards me […] She did sail. She wore a long frock and seemed about fifteen feet tall with all her hair piled up in something like a crown on top of her.

Next, the father appears.

Mr Tulisi, the Reverend, appeared from behind his wife. It would be nice to say they made a good pair but they didn’t. He was as little as she was big. I had sometimes thought that there would be a horrible mess if she mistook him for a cushion, shook him, planted him down and then sat on him.

Later on, a female peer (later on, a love interest) is introduced. She has brought round a tin of baking.

‘Anyone ever tell you you’re a right pain, Sharon-Mary? I said. ‘Sit down if you want to.’ […] Sharon-Mary looked at me for a moment. She had brown eyes, a load of freckles and nearly as much dark red hair as Mrs Tulisi had black. She was short, sort of roundish and not quite plump. Very busy was Sharon-Mary. All the time. She had a face that laughed and smiled a lot. It wasn’t laughing or smiling now […] “make my coffee. One spoon of sugar and a drop, no more, of milk. I’m training to have it black.” She settled into her chair in a way that told me she was there to stay.

I knew I was about to hear something about myself and while I was all ears I was a bit scared, too. I gave her the coffee and cut the cake. She waved the cake away.

“It’s for you. Mum never knows when to stop baking at Christmas and with my weight problem…”

“You’re not that fat,” I said, nicely.

“You’re not that fat” is hardly reassurance to someone who clearly is. By denying the obvious, such reassurance only underscores the idea that being fat is terrible. The above is an example from the 1990s but hasn’t changed. Take the song “I like em big, I like em chunky!”, ostensibly a celebration of thicc. This doesn’t stop the female object of the singer’s attention from exclaiming in mortification when the singer suggests she is big and that he likes it. The gag in the line of this comedic song is that he then changes his line to “I like your big ole heart”, when he clearly meant to refer to the size of her body. (He then gaslights her by calling her crazy, but that’s a different story.)

I like them witty, I like them smart

(With brains)

Girl, I like your big

(What you say?)

Your big ol’ heart, what?

Girl, you’re crazy, she drive me crazy

(Crazy)

ACCEPTABLE WAYS OF BEING FAT

This piece — and other praises of Dumplin’ that I’ve seen — talk about the book as if it’s entirely fat positive. It’s not. The main character’s dearly beloved late aunt died of fatness. Really, of fatness. She died of deathfat. Watching TV. Alone. The book doesn’t imply that Aunt Lucy was unloveable, but it absolutely uses her to embody the equation of fatness with tragedy. If you’re deathfat, you’ll die, you’ll die alone, you’ll die watching tv, and your low income family won’t be able to afford a coffin to fit you in. Plain tragedy.

In addition to Aunt Lucy, there’s another secondary character, Millie, who waddles:

“Millie is that girl, the one I am ashamed to admit that I’ve spent my whole life looking at and thinking, Things could be worse. I’m fat, but Millie’s the type of fat that requires elastic waist pants because they don’t make pants with buttons and zippers in her size. Her eyes are to close together and her nose pinches up at the end. She wears puppies and kittens and not in an ironic way”.

In Millie, fatness is pathetic. The phrase “Millie’s the type of fat that…” specifically calls her a “type.”Stereotype, archetype, not a full human. Readers are expected to recognize the type. Millie’s the icky “type” of fat, present for contrast, present so that Will, the protagonist, can be fat in a different way — a way that readers can like or feel fine about.

Why do we need to throw some fat characters to the wolves in order to offer a loveable fat protagonist? Is it a plea to the wolves? Is it bargaining? If we offer Aunt Lucy and Millie as sacrifice, can we be allowed to love the fat protagonist?

For Will, the protagonist, Dumplin’s message is mostly fat positive. But even for her, there’s this sentence: “For the first time in my life, I feel tiny. I feel small. And not in the shrinking flower kind of way. This feeling: it empowers me”. Why is power be symbolized as smallness? Why employ the equation of smallness with power? How does this not reinscribe hegemonic fatphobia?

Do pick up Dumplin’. Do read it. Do give it to teens. But this is a great chance to have analytical conversations about literary portrayal of fatness. Dissect it. We can praise and relish exciting aspects of fat positivity without ignoring hegemonic, fatphobic aspects from the same source. We must.

diceytillerman

IT STARTS WITH PICTURE BOOKS

Children’s stories are full of weird food messages, but perhaps the weirdest to me is the idea that a preschool market can — and should be able to — get jokes about dieting. See The Song of the Zubble Wump.

The obvious answer is that these jokes aren’t really meant for kids — they’re meant for the adult co-reader.

You’ll probably only find them in relation to anthropomorphized animals. Large animals such as elephants and mammoths are most likely to be the butt of this joke. Being built that way by nature, dieting simply won’t work, and that’s the root of the humour. In one of the later Ice Age movies Manny tells Ellie (both mammoths) that her butt is big. The joke is that Ellie doesn’t realise at first that he means this as a compliment. She takes offence, as all female characters must, because being fat is the absolute worst.

And that’s the message here, right? That being big is unacceptable, even if you’re naturally so.

It doesn’t take any experience with dieting to get that. Young readers get that.

The Lighthouse Keeper’s Lunch by Ronda and David Armitage is another picture book example written around diet culture.

Every day, Mr Grinling the lighthouse keeper cleans & polishes his light to make sure it shines brightly at night. At lunchtime he tucks into a delicious lunch, prepared by his wife. But Mr Grinling isn’t the only one who enjoys it. Can Mrs Grinling stop the greedy seagulls stealing the lighthouse keeper’s lunch?

Though it’s not evident in the marketing copy above, Mr Grinling’s wife makes him row his boat from the lighthouse to shore as part of her weight loss plan for him. This book was first published in 1977. Diet culture was yet to really ramp up. Connection was yet to be made between diet culture and eating disorders.

IT GETS WORSE IN MIDDLE GRADE

There needn’t be fat characters in a book for the book to be saying something about body size. When a character is constantly described as slim/slender/size six etc for no good reason in the story, the ideology is that body size is important outside every other achievement.

If you read the Sweet Valley High series, you can probably tell me off the top of the head that the twins were ‘perfect size sixes’, because it was mentioned a lot.

Those who read the Babysitters Club series will remember that Claudia is always described as thin with good skin — all this even though she eats lots of forbidden junk food, like the Gilmore girls.

NORMALISATION OF EATING DISORDERS, OR A HOW-TO GUIDE?

A series of Gossip Girl novels by Cecily von Ziegesar has recently appeared in stores. These stories feature a group of girls from New York City who live a pampered lifestyle and whose concerns revolve around fashion, friendships, and boys. Bulimia is framed as just part of the lifestyle:

Fudge-frosted brownies on little white plates sat temptingly on a shelf at eye-level. [Blair] picked one up, examined it for any defects, and then put it on her tray. Even if she actually decided to eat it, she could always throw it up later.

It wasn’t much, but at least she had that much control over her life.

For girls who are unhappy about their body image, this normalization of a symptom of a psychiatric illness is surely dangerous. This narrative privileges disordered eating as an expression of control and offers bulimia as as sort of twisted recompense for disappointment.

Carolyn Daniel, Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

FAT AS A SHORTCUT FOR BAD CHARACTER

YA fiction often positions fat as shorthand for countless negative qualities the writer is too unmotivated to develop – like presenting bullies as fat kids, which reinforces fatness as something sinister and deserving of scorn – or as the genesis of a butterfly story, which reinforces fat as a quality one must jettison to uncover the true self (which naturally is thin and beautiful). Of course there are other ways in which fatness is portrayed, but those two immediately came to mind.

Shapley Prose

If you’re fat, you’re the ugly friend. You’re the villain. You try too hard, and people pity you. You’re jealous of all the “pretty” girls. You’re the sassy best friend with a brain full of quips and no character depth. You don’t get the guy unless he’s also been presented as equally undesirable, and then you’re a loser couple to laugh at.

Adventures in Storyland

THE PIRATES! BAND OF MISFITS (2012)

The Pirate Captain has the obligatory parrot on his shoulder, standing in as his ‘trophy wife’. The running joke is that the parrot is bigger than it should be. “She’s not fat — she’s just big-boned”, exclaims the captain defensively. This has the entire ship in fits of laughter, and is the turning event when the captain decides he must prove his worth as their true leader.

This joke wouldn’t work, of course, if there were not the cultural assumption that powerful men must have beautiful women on their arms — or in this case, beautiful parrots on their shoulders. A man whose woman (or his female parrot companion) can’t possibly be fit to be leader unless he finds himself a female who fits the narrow constraints of acceptable body shape. A man’s status must match his woman’s beauty. Stereotype thusly reinforced.

Later, when Queen Victoria enters a room on a horse, the queen is exaggeratedly large (as she is always depicted) and the horse is ridiculously small: a visual joke about size which is as powerful as anything voiced. In another scene someone says, “A minute on the hips, a lifetime on the hips.” A ridiculous axiom in the first place. All it does is bring unhealthy messages about food guilt into a comedy designed for kids, who shouldn’t have to have to hear such rubbish.

THE FAT MAN BY MAURICE GEE

This book is widely studied in Year 9 throughout New Zealand high schools.

Maurice Gee’s description of Muskie’s obese body in The Fat Man evokes disgust and abjection. His gross rolls of fat seem to provide evidence of contamination by the (unhealthy, fat-laden) foods he has eaten. He embodies excess; his body shows that he has consumed more than his fair share, suggesting that somewhere, someone has gone without. Obesity is, in Western culture, indicative of excessive appetite, of a lack of self-control, of laziness, and of an unwillingness to conform to accepted paradigms of beauty. Arguably it also signifies a lack of morality. Susan Bordo argues that the firm, developed body has become a symbol of “correct attitude;” that one “cares” about oneself and how one appears to others. While muscles express sexuality, it is a controlled, managed sexuality that is “not about to erupt in unwanted and embarrassing display.” In contrast, the obese body signifies the wrong attitude and a lack of care about body image. It connotes voracious and uncontrolled (sexual) appetite.

Carolyn Daniel, Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

FAT PHOBIA IN THE WORK OF ROALD DAHL

Fantastic Mr Fox (film adaptation)

Roald Dahl did not like fat people. (I wonder what he made of his granddaughter becoming a plus-size model.) The man himself was ‘rakish’. I mean, he looked like a rake, which is what ‘rakish’ should probably mean. In fact it means: Having or displaying a dashing, jaunty, or slightly disreputable quality or appearance. But I’m not going to let common definitions stand in my way here.

One could argue that Roald Dahl didn’t much care for little people either, or any kind of person at all, really, especially short men (‘You might say he’s kind of a pot-bellied dwarf of some kind’), but Dahl makes sure to specify that Walter Boggis is fat because he eats three chickens at every meal, perpetuating the erroneous message that fat people are fat because they eat a lot. (The descriptions of the farmers are what makes Fantastic Mr Fox what it is, and Dahl’s descriptions are quoted verbatim in the film.)

The science behind weight-gain is complicated, this simplistic view of overweight and obesity — the view that fat people get fat because they eat a lot — is simplistic and flat out unhelpful. Robert Lustig, who knows a lot more than most people about this topic, being an endocrinologist, takes a far more modern approach toward cause and effect when it comes to obesity: fat people eat a lot because they’re growing. If this is true, then blaming fat people for eating too much is like blaming a strapping teenage boy for eating too much.

Back to the film, Badger’s voice over explains: ‘He’s unbelievably fat — which may be genetic — but he also eats three boiled chickens smothered with dumplings every day for breakfast, lunch, supper, and dinner. That’s twelve in total, per diem’. The phrase ‘which may be genetic’ smacks to me of self-consciousness, since the filmmakers understand full well that this is not a very nice thing for Badger to point out. These filmmakers steamroll right over the complexities, however, and sure enough, Boggis is a greedy, unpleasant man. His overweight body correlates with general slovenliness: ‘never takes a bath’. The audience sees him picking his ear.

But then of course we have Farmer Bean, who provides comic effect by being the opposite. So are Dahl and the filmmakers really poking fun at fat people, if they’re equally willing to have a go at skinny ones?

Well, I don’t know if they’re having a go at skinny ones, or at the eating disordered. Badger’s voice over explains: ‘He’s probably anorexic, because he never eats anything. He’s on a liquid diet of strong, alcoholic cider, which he makes from his apples’.

Sure, ‘not eating’ is technically the definition of ‘anorexic’ (babies are ‘anorexic’ when they fail to drink milk), so Farmer Bean is unquestionably anorexic, but I squirm a little at this, because the popular interpretation of ‘anorexic’ is of ‘anorexia nervosa’, a serious mental health disorder which is more deadly than any other mental health disorder. Especially for young women.

So was that line really necessary? Really? When food related disorders are at an historic high? And if it’s really a case of sticking to the original story without politically correct modifications, is this really the sort of story that we need to bring back to life from 1970? As it turns out, I’m a big fan of modernising classic tales. Politically correct re-written versions of Enid Blyton’s Famous Five? Gimme that any day. I loved those tales, but I don’t want my daughter to think that boys and ‘tomboys’ have all the fun.

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (the book)

Roald Dahl believed that adults have a relentless need to civilize “this thing that when it is born is an animal with no manners, no moral sense at all.” His story, Charlie and the Chocolate Factor, drives home his views. Charlie is a polite, passive child. He respects his elders, is hard working, unselfish, thoughtful, and he knows how to control his appetite. Every year on his birthday, Charlie receives from his poverty-stricken family “one small chocolate bar to eat all by himself”.

He would place it carefully in a small wooden box that he owned, and treasure it as though it were a bar of solid gold; and for the next few days, he would allow himself only to look at it, but never to touch it. Then at last, when he could stand it no longer, he would peel back a tiny bit of the paper wrapping at one corner to expose a tiny bit of chocolate, and then he would take a tiny nibble — just enough to allow the lovely sweet taste to spread out slowly over his tongue. The next day, he would take another tiny nibble, and so on, and so on. And in this way, Charlie would make his sixpenny bar of birthday chocolate last him for more than a month.

This passage exemplifies the qualities Dahl apparently appreciates in a child: civilized manners, frugality, and, most importantly, restraint and control. It is interesting to note, however, that Charlie finds his golden ticket to the Chocolate Factory through an act which is ostensibly transgressive. When Charlie’s father loses his job the food situation at home becomes “desperate. Breakfast was a single slice of bread for each person now, and lunch was maybe half a boiled potato. Slowly but surely, everyone in the house began to starve.” “Every day Charlie Bucket grew thinner and thinner…The skin was drawn so tightly over the cheeks that you could see the shapes of the bones underneath. It seemed doubtful whether he could go on much longer like this without becoming dangerously ill”. Charlie finds a fifty pence coin in the snow and, instead of taking it to his parents so that they can buy food for whole family, he goes straight to the nearest shop and buys a bar of chocolate. (Incidentally, the shopkeeper strikes Charlie as being particularly “fat and well-fed”. Charlie “crams large pieces” of the chocolate bar into his mouth. Significantly, he is described as “wolfing” it down. “In less than half a minute, the whole thing had disappeared down his throat”. Charlie buys a second bar, reinforcing his transgression, and it is under the wrapper of this Whipple-Scrumptious Fudgemallow Delight that he discovers the Golden ticket. Roni Natov points out that questing heroes often have to “break some taboo” and “revolt” against the familial/social structure in order to create change. Tradition must be subverted so that evolution can occur. This, she reveals, is at the heart of the hero’s quest. It is significant that Dahl carefully constructs Charlie as being in extremis before his transgressive act takes place.

Carolyn Daniel, Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

In contrast, all the other children in the story who find golden tickets, have excessive appetites and desires, and show the deleterious influences of consumer-media culture. Veruca Salt is an acquisitive, impulsive and selfish consumer of material goods. She is acquisitive, impulsive and selfish consumer of material goods. She screams at her father, lying on the floor for hours, “kicking and yelling in the most disturbing way” until she gets what she wants, producing the ultimate display of “pester power.” Nine-year-old Mike Teavee, on the other hand, is described by Dahl as a “television fiend”. He is an avid consumer of gangster films, the more violent the better. He wears “no less than eighteen toy pistols of various sizes hanging from belts around his body” and indignantly resists being deprived of the TV even for a short time. He thinks that gangster movies are “terrific… especially when they start pumping each other full of lead, or flashing the old stilettos, or giving each other the one-two-three with their knuckledusters! Gosh, what wouldn’t I give to be doing that myself! I’ts the life, I tell you! It’s terrific!” The Oompa-Loompas’ song provides the vehicle for Dahl’s critique: television is a “monster”; children should be kept away from “the idiotic thing”. It hypnotizes them, making them lethargic and mindless to the point of being “absolutely drunk”.

Carolyn Daniel, Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

Daniel points out that Dahl was an early writer to hold this view, which has since become a lot more common. Though Mike Teavee is an example of an over-consumer of media, it is Augustus Gloop of course who is an overconsumer in the most literal sense — he eats too much.

Gloop’s body, and his face in particular, seem to embody the food which produced it. His head is a currant bun! Furthermore, reference to Claude Levi-Strauss’s raw-cooked dualism, which he aligns with nature/culture, suggests that Augustus’s doughy face evolkes notions of precultural primitivism and irrational mindlessness.

Carolyn Daniel, Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

Also of note: Dahl blames Gloop’s mother for overfeeding her child and making him fat.

In psychoanalytic terms, it could be argued that Augustus has failed to properly separate from his mother, signified by his insatiable and transgressive desire for food. He is stuck in the oral phase, the phase of maternal influence. Food is the wrong object for his deire; he ought to have turned to the father/phallus in order too achieve proper masculine subjectivity. Augustus is connoted as monstrous and denied agency by his inappropriately directed and excessive desire.

Carolyn Daniel, Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

The more modern version of Augustus Gloop is of course seen in Harry Potter.

Issues of Class

With regard to Dahl’s construction of these characters…notions of class and race are also implicated. Although Charlie has middle-class manners and mores, he is an idealistic representation of the British working class. Veruca Salt belongs decidedly within the despised nouveau riche category and is presumably American, since her father is “in the peanut business”. Violet Beauregarde and Mike Teavee are also affiliated with America; Violet by her incessant gum-chewing and Mike by his penchant for American Westerns and gangster movies. Augustus’s last name suggests he might be German. The class and race issues implied here are significant in relation to the nuances of excessive and vulgar appetite and childish monstrousness. There are marked differences between historical notions of childrearing in britian and America. The austere diet of British children was deemed to have character building properties while, in contrast, American childrearing methods were seen to be vulgar and overindulgent and associated with the nouveau riche. Dahl’s cultural conservatism marries with Dick Hebdige’s claims that populist discourses about culture and taste in Britain in the 1930s-60s tended to focus on the “leveling down” of moral and aesthetic standards and the erosion of fundamentally British values and attitudes. This perceived decline in standards was believed to stem from “American ization” (an influx of American mass culture encompassing good,s production techniques, music, etc.), and reflected fears of the homgenization of British society.

Carolyn Daniel, Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

The modern reader can even make the link between the hammering down of Gloop’s body in the story and the American trend for plastic surgery, which has also crossed the Atlantic.

FAT PHOBIA IN YOUNG ADULT FICTION

Sometimes the dis/approval of body type is quite subtle. It can be achieved in a single word. In the young adult novel Glow by Amy Kathleen Ryan (2011), the main female character is described as ‘slender’ in the introductory thumbnail description. When the mother is introduced, we are told that mother and daughter look similar, but the mother is ‘not as slender’. Then again, at the beginning of chapter five we’re told:

One moment Kieran had been staring at Waverly’s slender back, imploring silently, Don’t go. Get off the shuttle.

Not only is the ‘slender’ thing mentioned again for no good reason to the plot, the reader is treated to yet another vision of a girl through the pervasive male gaze. Even in fiction — stories set in wholly imagined futuristic worlds, no less — girls can’t escape this constant judgement on their bodies.

THE MAKEOVER TROPE

At TV Tropes you’ll find a breakdown of various types of makeover scenes which are very common in ‘ugly duckling’ stories. Many of these are coming-of-age stories.

[Many narratives feature] the transformation or makeover of children’s bodies so that they comply with accepted paradigms of beauty or, in the case of the younger children, properly controlled childhood. John Stephens has shown that, semiotically, the trope of the makeover, so often used in contemporary teen fiction, is frequently framed as a central metonym of growth and a movement toward subjectivity and maturation. It supposedly demonstrates to the character concerned that “she can transform her life and thus realize her full potential.” On the one hand, such discourses reiterate the notion that bodies, especially female bodies, are transformable, and on the other, they act to endorse cultural beauty paradigms and the imperative that female bodies should be transformed. … The changes… reflect the individual’s movement toward a more mature self. Thus “what appears inscribed on the body’s surface [is seen to] function as a pointer to the depths within. In countless movies, magazines, and teen (or young adult) novels, aimed at girls, the make over is shown to be the way to transform the self and notably, to achieve agency and happiness through social acceptance. Most significantly, even when a range of body morphologies is confirmed as “natural”, it is always the slimmest body types that are valorized.

Carolyn Daniel, Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

HAVE THINGS CHANGED LATELY, THOUGH?

Not a lot.

- Logan (2017) — the script forces Hugh Jackman to call a woman a “fatass”

- Bill Burr routine (2017) — he rants for 7 minutes about fat people

The Modern Taboo

Anorexia seems to be considered an acceptable topic for young readers. Obese children, on the other hand, are rarely featured in contemporary children’s literature and are unlikely to be explicitly condemned as they often are in the classics. …Dudley Dursely…proves to be an unusual exception.

Carolyn Daniel, Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

Voracious Children was published 10 years ago, and in good news, the fat acceptance movement and some exciting new authors seem to have had a positive impact on the young adult landscape in particular. Until recently the standout examples of fat characters in children’s literature were:

- Blubber by Judy Blume — fat bodies used as learning tools for others

- The Cat Ate My Gymsuit by Paula Danziger — but the sequel completely undoes any fat-positive messages

- When Zachary Beaver Came to Town

- Nothing’s Fair in Fifth Grade by Barthe DeClements

- The Fairy Rebel by Lynne Reid Banks

- Madeleine L’Engle only ever has fat characters in her books who are morally bad

Rainbow Rowell’s Eleanor & Park is the best YA novel I have had starring a fat main character* because:

- Eleanor is still fat even when she doesn’t get enough to eat, which to me reads as a sign of poverty, which it is in the real world, rather than a symptom of greed or bad character

- Eleanor is not depicted as a ‘beautiful girl’ but in a fat body and there is never any ‘If only she lost weight she’d be hot’ sentiment

- She ends up in a romantic relationship with someone who does not have body image issues. It’s not a Shrek-like ‘Know your level’ sort of message.

- Eleanor has a fulfilling teenage sex life and her overweight is a non-issue when it come to that.

- Rainbow Rowell also avoids that thing where every fat girl has to find her true love by giving us a bittersweet ending.

*It is never actually clear in the story whether Eleanor is genuinely fat or if she just thinks she is, which might be seen as problematic.

Eleanor & Park is a part of a new wave of YA novels written by (mostly female) authors who have a much better handle on fat politics than authors who came before. Some examples from around the Internet (which is probably mostly to thank for fat acceptance in the first place):

- Sweet by Emily Laybourne

- Dumplin‘ by Julie Murphy

- The Girl of Fire and Thorns by Rae Carson

- Looks by Madeline George

- Earthly Delights by Kerry Greenwood

- Gabi, A Girl in Pieces by Isabel Quintero

- My Big Fat Manifesto by Susan Vaught

- Everything Beautiful by Simmone Howell

- Food, Girls, and Other Things I Can’t Have by Allen Zadoff (about a boy rather than a girl)

- Nimona, a graphic novel by Noelle Stevenson

- Big Fat Manifesto by Susan Vaught

- Hungry, Crystal Renn’s memoir

- This Book Isn’t Fat Its Fabulous by Nina Beck

- All About Vee by C. Leigh Purtell

- Fat Hoochie Prom Queen by Nico Medina

One of the problems with the marketing and packaging of books about fat girls, though, is that the book covers often depict food, whereas almost every YA novel with a beautiful protagonist shows the protagonist, or at least a part of her body on at least one of the cover versions. (Often headless, admittedly.) Where are all the headless fat girls on book covers?

Modern Books To Avoid (due to problematic/conflicting messages)

I have not read many of these. Some I have tried reading and given up partway through. Others I do appreciate as stories, but when I look more closely at the fat politics I definitely know what people are talking about. If you’re looking quickly for a book a fat kid might love, perhaps make use of this list as a rough shorthand?

- Kill the Boy Band by Goldy Moldavsky

- Everyday by David Levithan

- Sugar by Deidre Riordan Hall

- Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone by J.K. Rowling

- Huge by Sasha Paley

- Artichokes Heart by Suzanne Supplee

- Looks by Madeleine George

- The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants by Ann Brashares

- Shrink to Fit by Doner Sarkar

- Staying Fat for Sarah Byrnes by Chris Crutcher

- Will Grayson, Will Grayson by David Levithan and John Green

IS IT POSSIBLE TO WRITE A FUNNY FAT JOKE?

There are some guidelines. I personally steer clear of reference to body size, as does Daniel Handler on principle — and did anyone even notice that he leaves physical description right out?

Would this be funny if the character wasn’t fat?

Incorrect response: I also laugh at skinny people so I can’t be fat phobic.

A comedy which does fat jokes well is Roseanne. The age of that show is telling — good fat jokes are rare as truffles.

Just Friends is also apparently a healthy representation of a fat character because the characters’s fatness is a part of their backstory and character arc. We can’t steer completely clear of depicting fat characters either, because that would be ‘symbolic annihilation’.

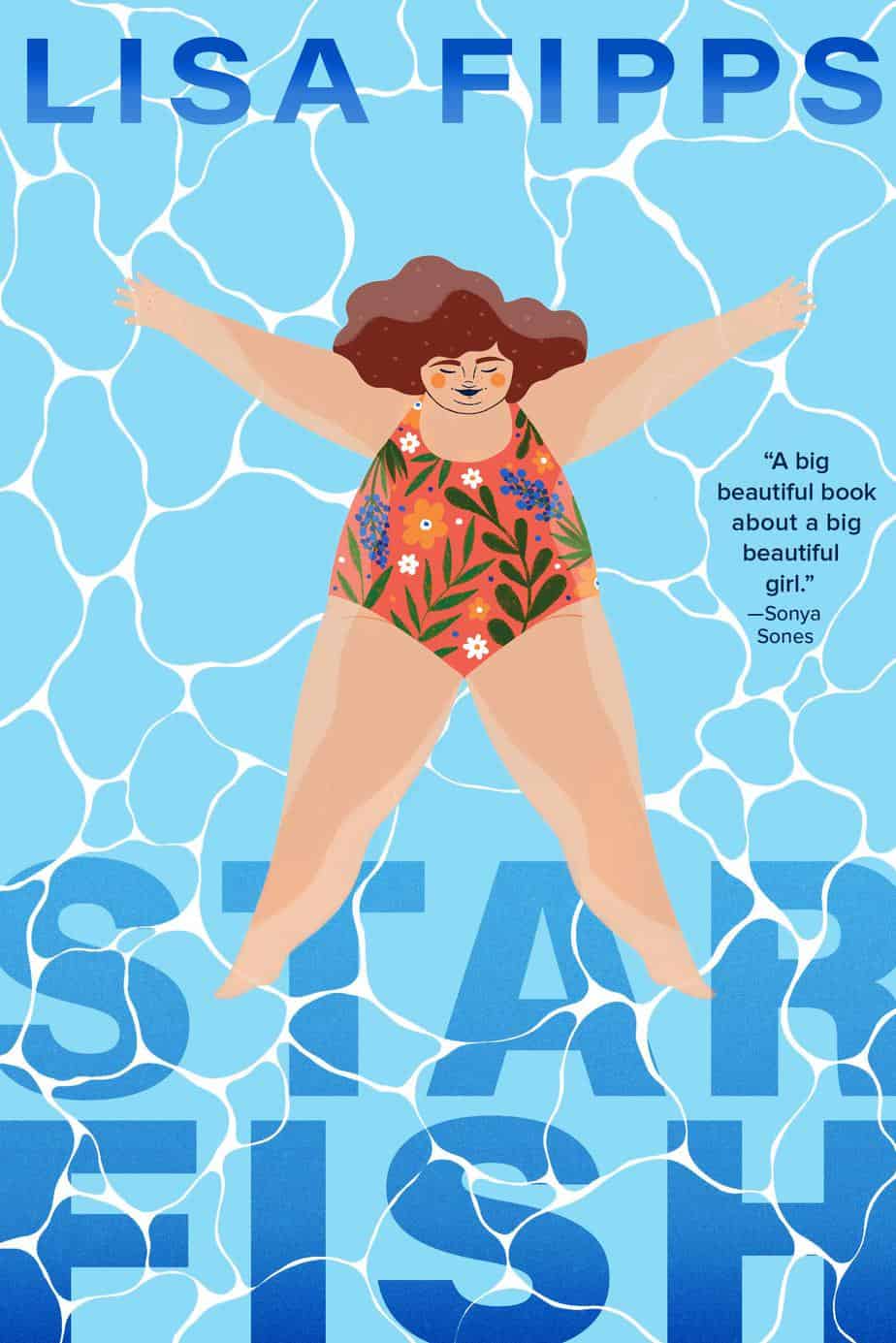

Ellie is tired of being fat-shamed and does something about it in this poignant debut novel-in-verse.

Ever since Ellie wore a whale swimsuit and made a big splash at her fifth birthday party, she’s been bullied about her weight. To cope, she tries to live by the Fat Girl Rules–like “no making waves,” “avoid eating in public,” and “don’t move so fast that your body jiggles.” And she’s found her safe space–her swimming pool–where she feels weightless in a fat-obsessed world. In the water, she can stretch herself out like a starfish and take up all the room she wants. It’s also where she can get away from her pushy mom, who thinks criticizing Ellie’s weight will motivate her to diet. Fortunately, Ellie has allies in her dad, her therapist, and her new neighbor, Catalina, who loves Ellie for who she is. With this support buoying her, Ellie might finally be able to cast aside the Fat Girl Rules and starfish in real life–by unapologetically being her own fabulous self.

FURTHER READING

As a man, I’m a big dude, but not outside the norm for such things. I am just barely fat enough to shop at what I call The Big Fat Tall Guy Store, and can sometimes find my size in your usual boy-upholstery emporia. Major clothing labels, like Levi Strauss, make nice things in my size, and I am never forced to wear anything that appears to have been manufactured at Mendel the Tentmaker’s House o’ Fashion. (Although those things do exist for men, too. Those terrycloth shirts with the waistbands? Oy.) I can order extra salad dressing or ice cream or anything else in a restaurant and have it arrive without comment; I can eat it in public without anyone taking a bit of notice, even if I am shoving it into my mouth while walking down a crowded street and getting crumbs all over my chest in the process. I can run for a bus or train without anyone making a snide remark. As a big guy, I’m big enough to make miscreants or troublemakers decide to take their hostility elsewhere. As a woman, I am revolting. I am not only unattractively mannish but also grossly fat. The clothes I can fit into at the local big-girl stores tend to fit around the neck and then get bigger as they go downward, which results in a festive butch-in-a-bag look—all the rage nowhere, ever. No matter how clearly I order a Coke in a restaurant I must be on a diet, and so I get a Diet Coke—usually with a lemon floating in it accusatorily, looking up at me as if to say, “This is as good as it’s going to get, lardass.” Wait staff develop selective amnesia about my side of fries or my request for butter, and G-d help me if I get caught eating (or even shopping) in public as a woman. Packs of boys follow me, mooing; women with aggressively coordinated outfits accost me in the grocery store to inform me that I can lose thirty pounds in thirty days and that they would love to help. There are pig calls (“Soooooooooieeeeeeeee!”) and the particular piece of performance art that is someone shuddering every time I take a step (to signify the seismic reality of my enormous, ground-shaking bulk). The fat woman I am some days does not view a stroll down a dark street with anything but barely disguised fear.

Part-Time Fatso” by S. Bear Bergman from The Fat Studies Reader, pg. 141

They say one of the gifts of getting older is you don’t care as much what other people think of you. And as I come to the end of my 30s this does seem true, with one notable exception. All the women I know, and I include myself, still spend far too much time engaging in ”confessional” food talk.

SMH, Would You Like Some Stigma With That?

Calling Melissa McCarthy a “Female Hippo” isn’t being a critic; it’s being a bully, from Hello Giggles

Where Are All The Fat Female [American] Politicians? from Jezebel

Self-acceptance has become a new form of defiance on television, especially among younger female comedians. Partly that’s because it’s refreshingly unusual. From Women on TV Step Off The Scales

Are Thin Women The Enemy? from BBC News

Fat from The Rumpus is a long read written about the experiences of being a lifelong overweight male.

Obesity Campaigns: The Fine Line Between Educating and Shaming from The Atlantic

The truth about fat women and self control from Live Science

The Privilege Of Assuming It’s Not About You from Sociological Images

Where disordered eating and poverty intersect: Very little is known about people experiencing food insecurity and eating disorders, but research is starting to come out about that. Anorexia is not just a white, middle-class, female issue.

Denarii Grace talks about weight stigma and disability, the reality of being poor and how it affects food choices, and white supremacy and fatphobia.

Not many sociologists talk about discrimination on the basis of looks, and I’ve found people in general are loathe to even admit there is a beauty hierarchy, preferring the narrative that everyone is beautiful in their own way.

Bonnie Berry is an exception. Berry uses the terms ‘looks-bias’ and ‘lookism’ to describe discrimination aimed at people due to the way they look.

Society has always been fixated on looks and celebrities, but how we look has deep ramifications for ordinary people too. In this book, Bonnie Berry explains how social inequality pertains to prejudice and discrimination against people based on their physical appearance. This form of inequality overlaps with other, better-known forms of inequality such as those that result from sexism, racism, ageism, and classism. Social inequality regarding looks is notable in a number of settings: work, medical treatment, romance, and marriage, to mention a few. It is experienced as limitations on access to social power. Berry discusses the pressures to be attractive and the methods by which we strive to alter our appearance through plastic surgery, cosmetics, and the like.

Berry also discusses cultural factors, such as the manner in which globalization of media, advertisements, and movies have trended toward homogenization, whereby we are all encouraged to appear tall, thin, white, and with Northern European features even if we are none of those things. She also analyzes the underlying social forces such as economic incentives that, on the one hand, channel us to be as physically acceptable as possible via the sale of diet pills and skin lighteners, and on the other hand, encourage us to accept ourselves as we are by selling us plus-size clothing. The book concludes with suggestions for equal rights extended to all regardless of appearance. Here, Berry describes budding social movements and grassroots endeavors toward an acceptance of looks diversity.

There is a saying that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, implying that beauty is subjective. But can it be said that ‘better looking’ people have more social power? This book provides a fascinating insight into the social stratification of people based on looks – the artificial placement of people into greater and lesser power strata based on physical appearance.

The author analyzes different aspects of physical appearance such as faces, breasts, eye shapes, height and weight as they are related to social power and inequality. For example, tall people are often associated with power, with tall people being seen publicly as more capable and thus more deserving of power than shorter people. The author moreover assesses how people’s physical appearance affects their chances of marriage, employment, education, and other social and economic opportunities. The book contributes to and differentiates itself from current literature by emphasizing sociological theory – including constructionism and critical theory – and research to understand the phenomenon of social aesthetics, a term coined by the author to refer to the social reaction to physical appearance.