In his book Home, Witold Rybczynski describes a typical European house:

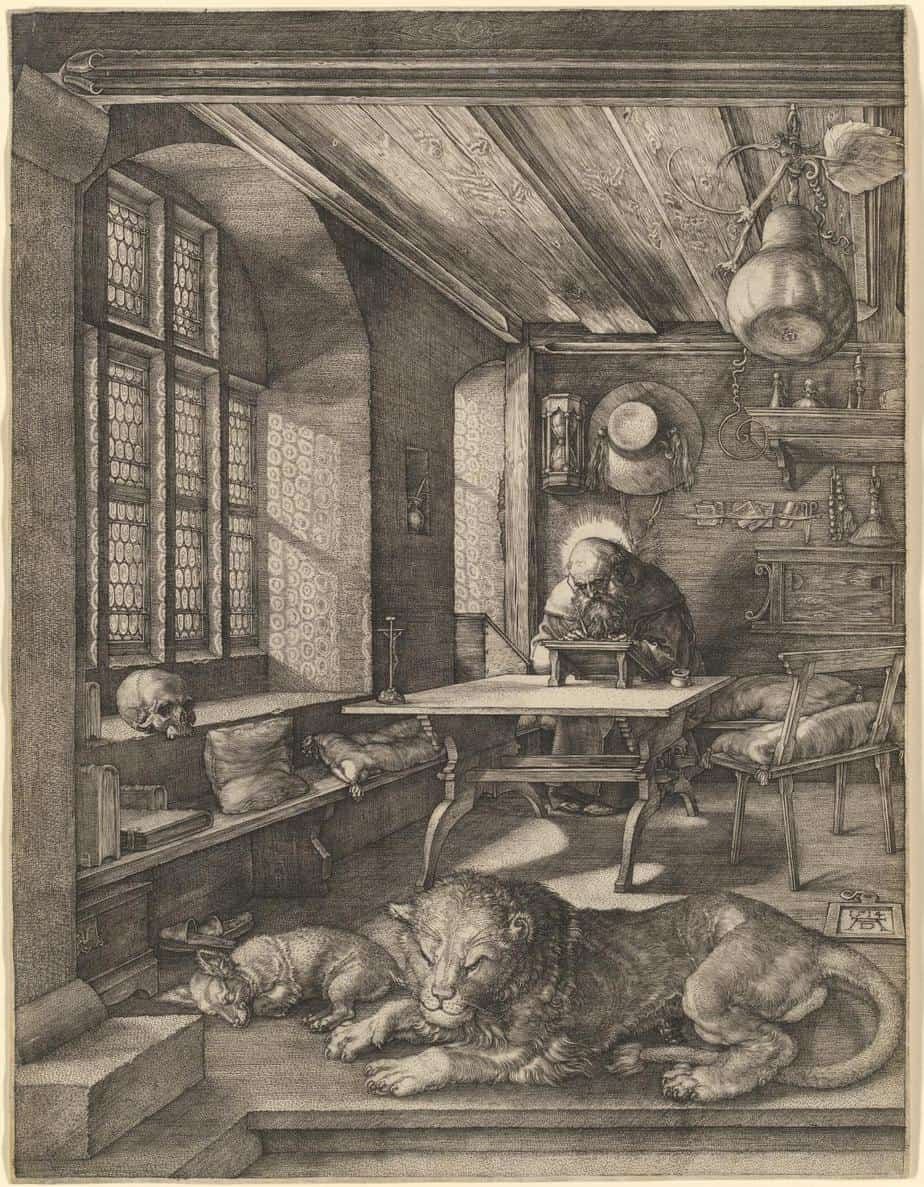

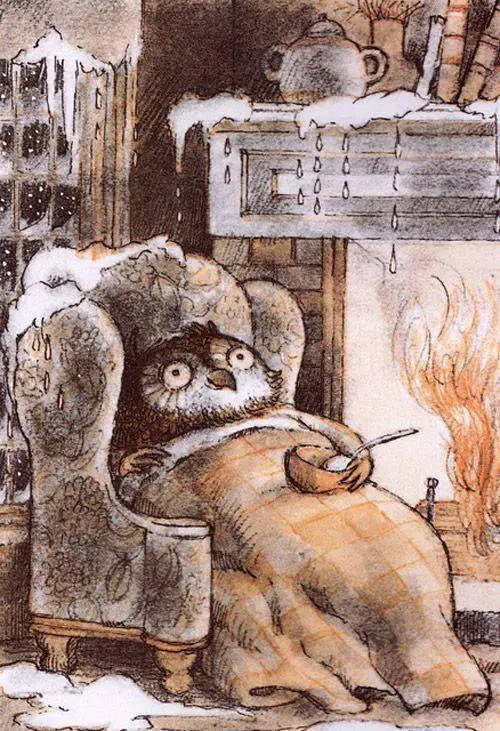

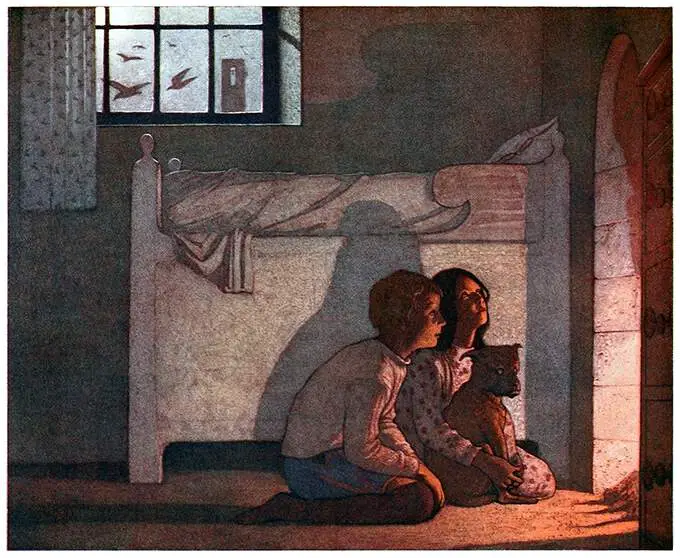

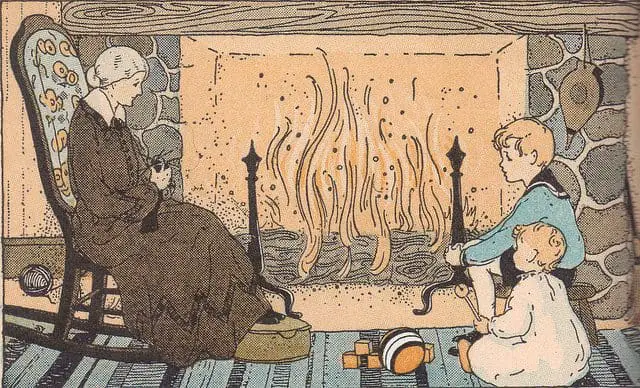

Heating was primitive. Houses in the sixteenth century had a fireplace or cookstove only in the main room, and no heating in the rest of the house. In winter, this room with its heavy masonry walls and stone floor was extremely cold. Voluminous clothing, such as Jerome wore [in the famous etching [St Jerome In His Study] was not a requisite of fashion but a thermal necessity, and the old scholar’s hunched posture was an indication not only of piety but also of chilliness.

Home, Witold Rybczynski

This is the 1514 etching he’s talking about:

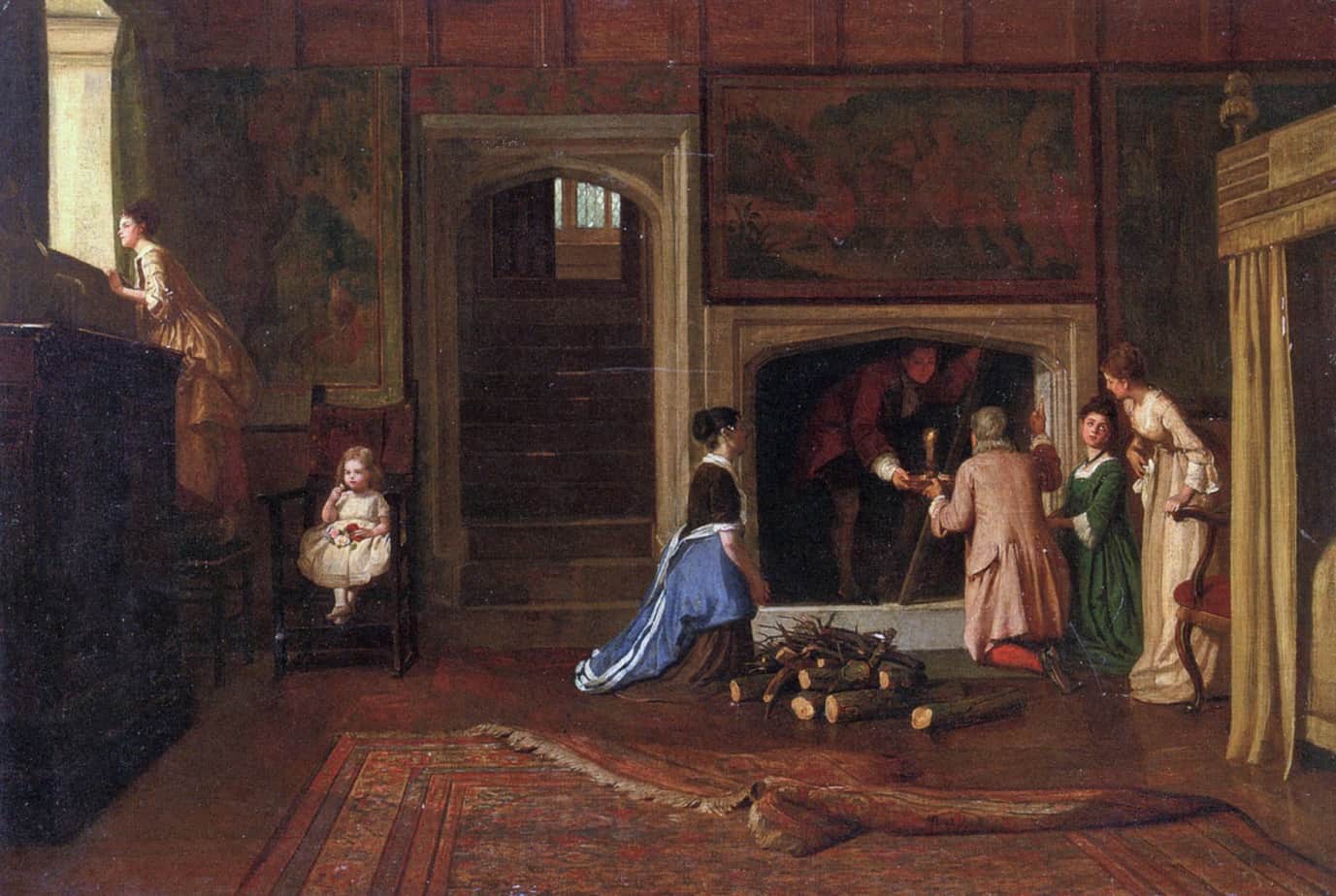

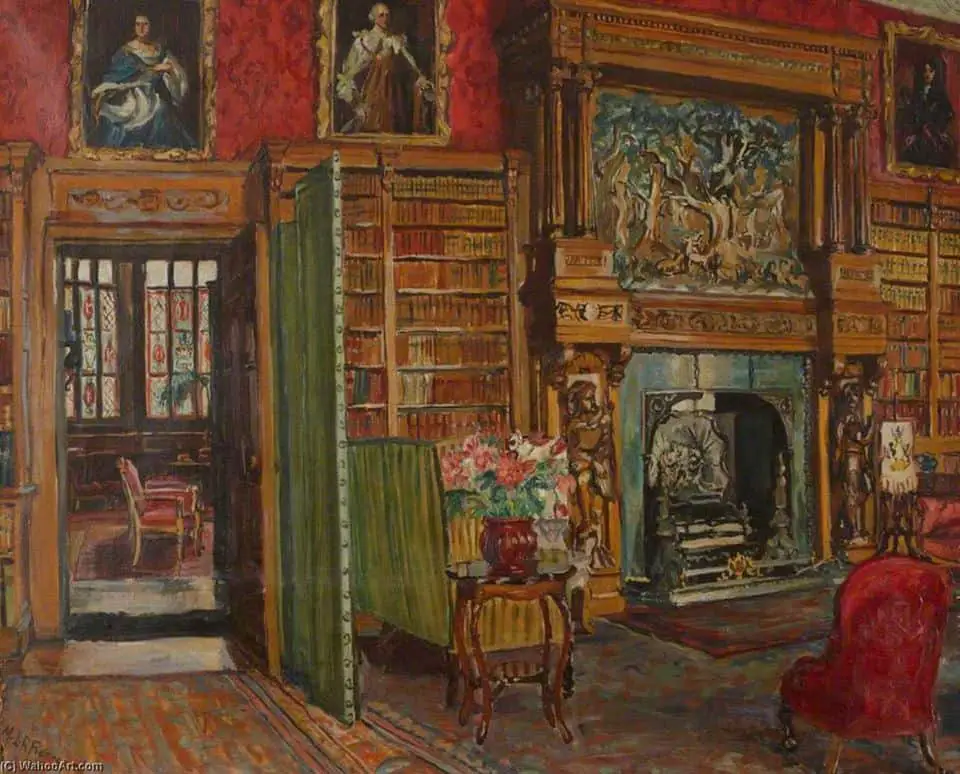

The mantled fireplace and chimney was first seen around the 11th century, but only saw wider use after the end of the Medieval period when houses were made more sturdily. They were terribly designed. The flues were massive, the hearths too deep. They filled rooms with smoke but heated them poorly. This situation continued into the 18th century. Those magnificent fireplaces you see in old castles were more ornamental than effective.

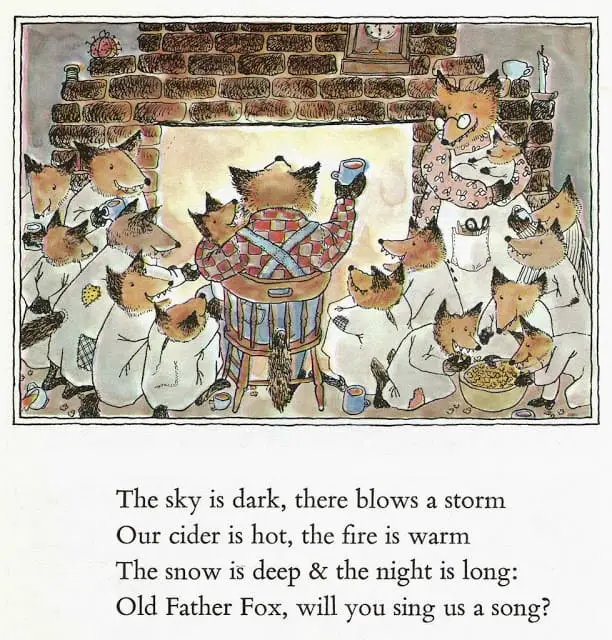

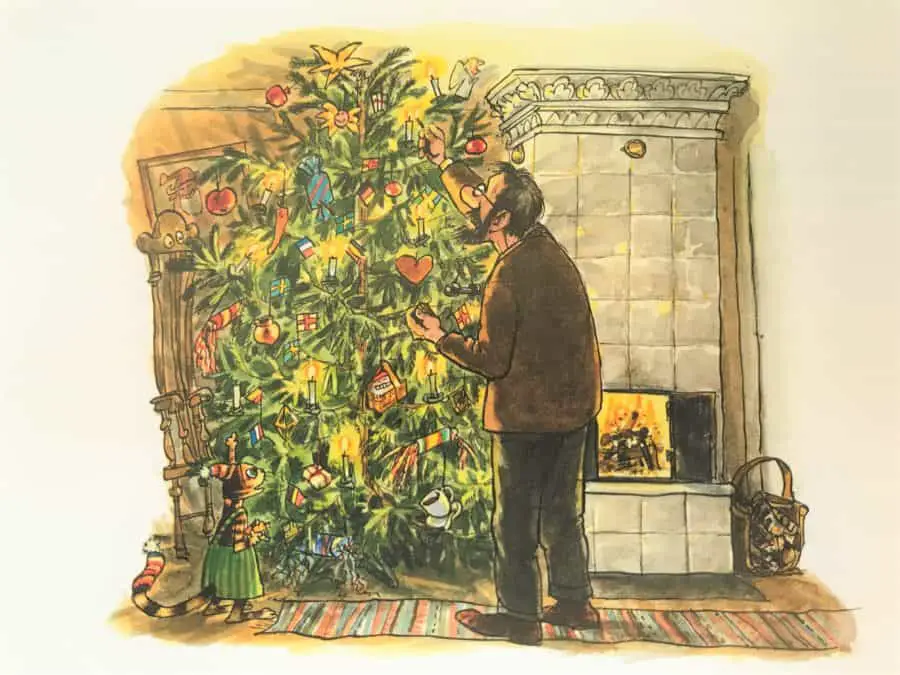

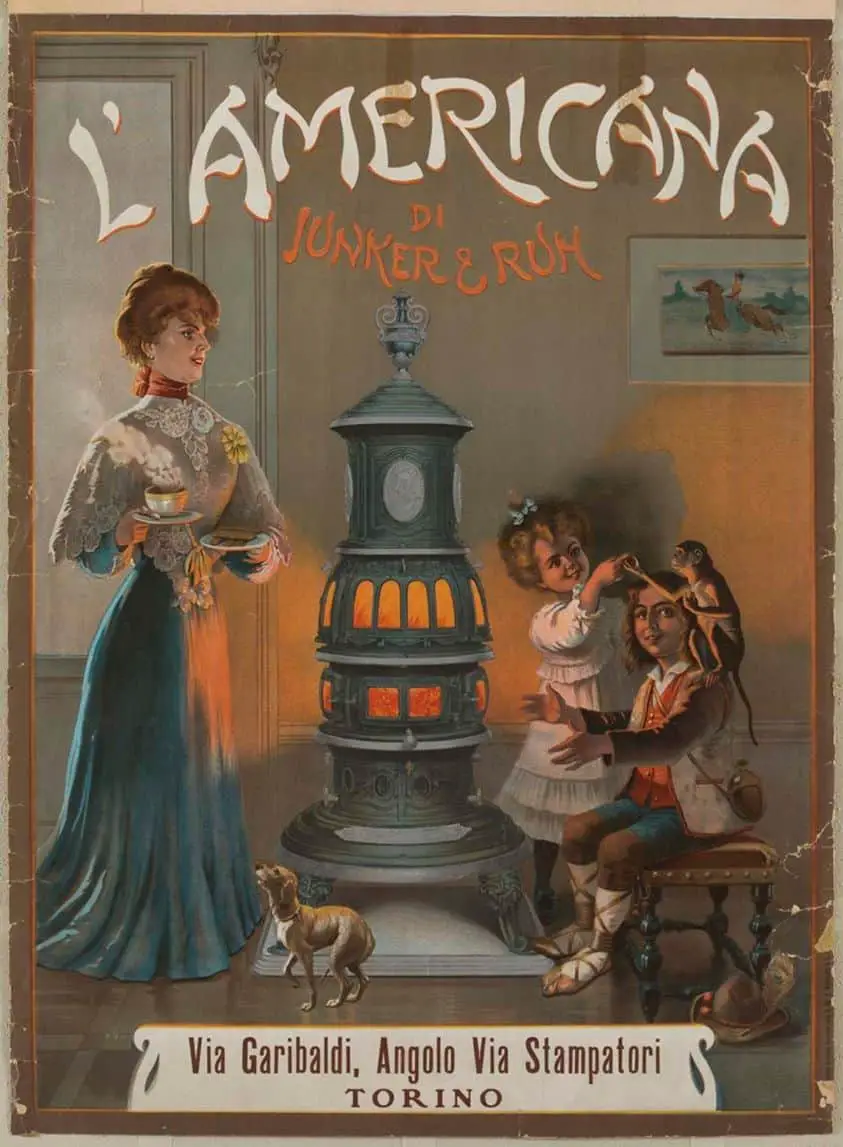

Germans invented much better stoves made out of glazed earthenware, and these caught on across Europe. Not quickly, though. It took 200 years (until the 1750s). Even though they did a much better job of heating, they were considered ugly to look at. This shows us how much prestige was attached to owning a majestic fireplace, no matter how useless it was at the job of heating.

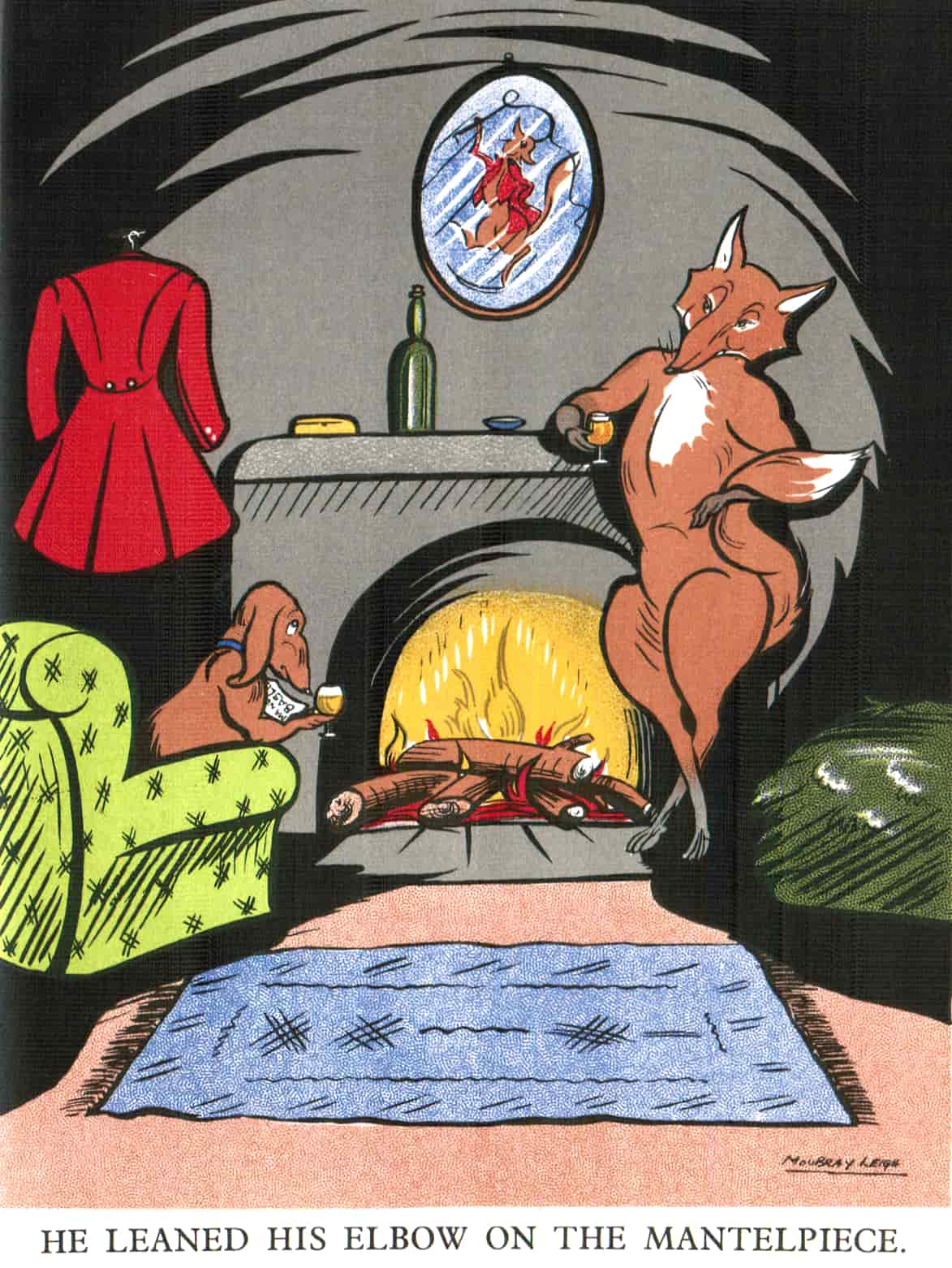

It was around 1720 that builders worked out how to build a proper chimney that cut down on smoke and improved combustion. People also started sitting with screens behind them as they relaxed by the warmth of the fire. This cut down on drafts. Rooms were also made smaller. Winters were now more pleasant.

A major improvement to the fireplace and stove first occurred not in a home but in an almshouse kitchen, and typically it was the work of neither an architect nor a builder.

Home, Witold Rybczynski

Rybczynski goes on to explain the varied career and interesting life of Count Rumford, whose biography has since been detailed on the Internet. Count Rumford proposed some changes which now seem super obvious:

These [1795 changes] involved narrowing the throat of the chimney, making the fireplace opening much smaller, and angling the side walls to radiate more heat into the room. The result was not only less smoke, but an improvement in heating.

Unlike toilets and electric lighting, these modifications to the fireplace caught on very quickly, partly because people could modify existing fireplaces themselves. As evidence, check out Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, which makes reference to a “Rumford”, meaning the new type of fire. Northanger Abbey was written only three years after Rumford invented the new kind of fireplace.

The spot right beside the fire is nice and warm, but it is also a dirty place. The hearth is an important symbol of Cinderella, also known as Ashputtle. (The name Cinderella originates from Cenerentola which comes from the Italian word “cenere” meaning ash.)

WITCH MARKS

As witch expert Diane Purkiss explains on Episode 83 of the English Heritage podcast:

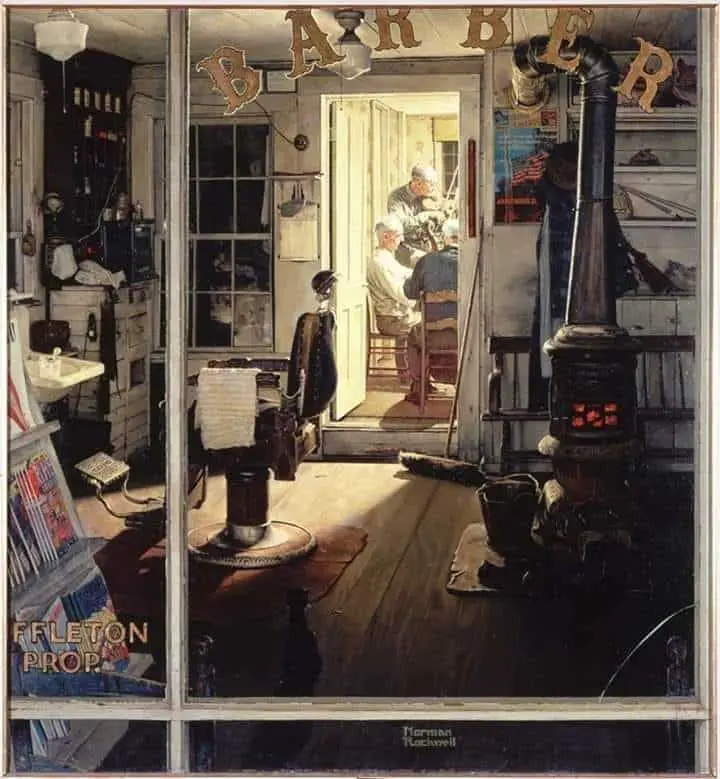

In England, witch marks are commonly etched into the bressumer beam over the hearth. Another common site is on a beam over the door, and also on window beams. These are all portals into the house, which explains the attempt to add extra guarding. Witchmarks function like an amulet, supposedly repelling maleficent entities who are trying to enter the home and take over.

There are a few different kinds of witch marks. One kind in particular are clearly meant to trap evil entities. These resemble mazes, where it’s assumed the evil entity will be compelled to try and navigate their way out of a circular shape. The circular shape is divided further by other curves. The entity will remain trapped inside, going round and round forever.

Another kind of witch mark, also very common, harks back to Catholic magic, and uses various Holy names. The most common ones use letters like N and V that fit together in a mazelike way but are also Latin prayer to the Virgin Mary. By invoking the pure, impenetrable body of the Virgin Mary you’re trying to help your house enjoy the same quality of purity and impenetrability. These kinds of witch mark are simply meant to repel the evil entity rather than confuse and trap them.

The mazelike ones are circular with a lot of curves inside them. They take a variety of forms, sometimes painted on, but most often incised. In imaginations, the spirit will be literally trapped within the curves in the wood.

The Virgin Mary witch marks are pointy rather than curved. Pointy edges and ends are thought to repel.

Folklore Podcast creator and host Mark Norman is joined by buildings archaeologist James Wright to explore the different ways in which both high status and the more common buildings were protected from harm by both their builders and their occupants, through the use of ritual marking. The discussion also takes in medieval graffiti along the way.

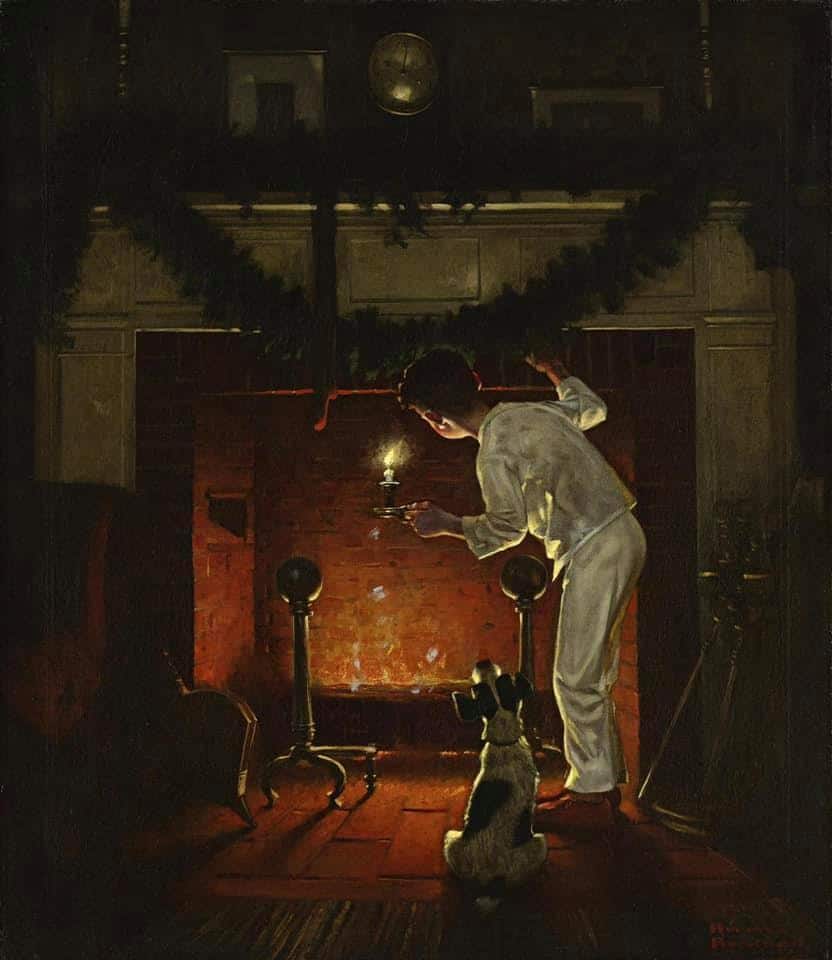

Header painting: Frank Holl – Faces in the Fire 1863-67