“The Hitch-hiker” is the second short story in Roald Dahl’s 1977 collection The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Six More.

- The Boy Who Talked with Animals

- The Hitch-hiker

- The Mildenhall Treasure

- The Swan

- The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar

- Lucky Break

- A Piece of Cake

This story was originally published in the July 1977 issue of the Atlantic Monthly.

Find it also in Dahl’s Eight Further Tales of the Unexpected, a section of The Collected Short Stories of Roald Dahl, first published 1992.

WHERE TO LISTEN

You may be able to unearth the BBC dramatization of this short story somewhere e.g. on YouTube. “The Hitch-hiker” was broadcast December 2012.

WHAT HAPPENS IN ROALD DAHL’S “THE HITCH-HIKER”

A wealthy writer drives his luxury car up to London to get a jewel fixed on his wife’s ring. On the way he picks up a hitch-hiker, because he remembers what it’s like to be poor and have luxury cars with a single occupant speed past you.

The hitch-hiker looks very much like a rat and speaks with a Cockney accent. He is cagey about what he does for a living but insists it’s a highly-skilled job. He dares the driver to show him how fast his car can go. Unfortunately they are pulled over by a cop on a motorcycle who issues a ticket. The cop tells the driver he’ll be getting a court summons, will definitely lose his licence and will most likely go to jail.

The hitch-hiker reassures the driver that he won’t be going to jail. They continue on their way towards London.

Although he’s very cagey about it, the hitch-hiker reveals that he is a professional pick-pocket, though he despises the word pick-pocket and prefers ‘fingersmith’.

Then he reveals all the items he has taken from the driver’s person and car, starting with his belt, then his shoelace, the wife’s ring…

The reveal: The fingersmith has also stolen the traffic officer’s log book. They decide to stop somewhere, start a bonfire and burn it.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS FOR “THE HITCH-HIKER” BY ROALD DAHL

- What do we learn about the narrator of this story? (Name, background, occupation, family)

- How does Dahl help us to like him?

- The narrator picks up a man on the side of the road. How does Dahl help us to be suspicious of the hitch-hiker?

- We can tell when “The Hitch-hiker” is set because Dahl gives us the exact model of the narrator’s car. When did this car come out? (For car enthusiasts: While you’re looking that up, compare the latest BMW and compare features.)

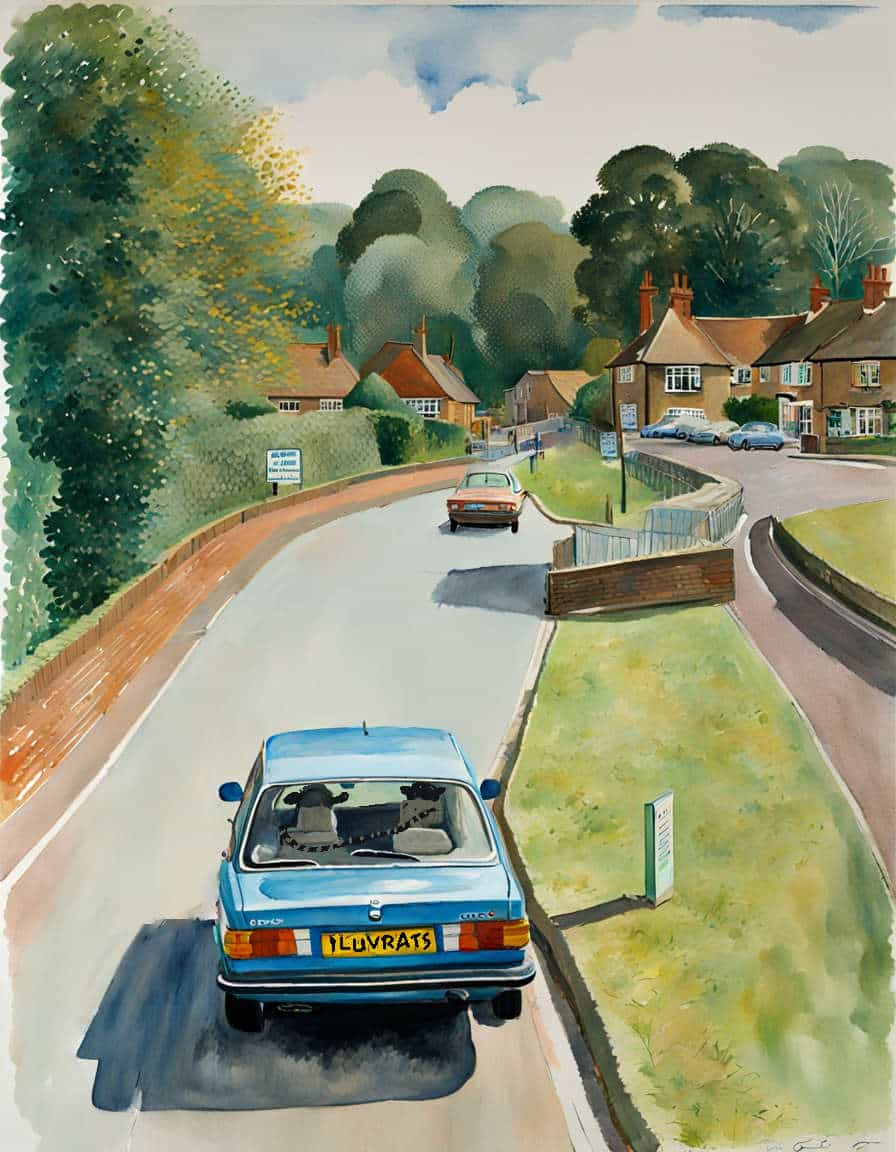

- Dahl also geolocates us by including the route in to London. Go to Google Maps or similar and plot some of the route. Pick a random spot on that route to investigate how the scenery looks these days by using the Street View functionality. How does it compare to Dahl’s description?

- We eventually learn that the hitch-hiker is a professional pickpocket. What does he prefer to call himself and why?

- Why do you think the hitch-hiker encouraged the narrator to prove the speed of his car, rather than simply believe him?

- When they are pulled over by the traffic officer, the officer is unappealing. How does Roald Dahl turn the officer into the hate sink character?

- What is the big reversal of this short story? (A reversal is when readers are forced to re-evaluate our interpretation of a story until that point.)

- Can you think of other stories which include hitch-hikers? When were these stories written? Do those stories encourage readers to stop for hitch-hikers, or not?

SETTING OF “THE HITCH-HIKER”

PERIOD

1974 or possibly a little later, depending on when the narrator purchased the car. I’m going to assume that this car enthusiast purchased it pretty much as soon as it came out.

DURATION

an hour or so

LOCATION

From what I can work out, this story is set on the A413, formerly known as the turnpike, a dual carriageway which starts at a place north of London known as “World’s End”.

There is a traffic circle at Chalfont St. Peter and immediately beyond there is a long straight section of divided highway.

“The Hitch-hiker” (probably referring to the Kingsway roundabout a413)

What the letters mean at the front of an English highway:

- M roads: motorways. These are the fastest roads (when there is not much traffic). They have blue signs. Examples are the M25, M1 and M4. The maximum speed for cars is 70mph.

- A(M) roads: an A road upgraded to a motorway. They have blue signs. An example is the A1(M). The maximum speed for cars is 70mph.

- A roads: The highway in “The Hitch-hiker” is an A road. These roads join big towns and cities. They have green signs. The most important ones usually have just one or two numbers (A2, A11 etc). Many are major routes, so the government looks after them. Others are looked after by the local council. Those with two or three lanes have a maximum speed of 70mph.

- B roads: B roads are not main routes, so are looked after by the local council. The road surface might be poor.

- C&D roads: These roads link small towns together. They might not be very straight and there will probably be lots of villages/towns to drive through. The road surface might be poor.

- Unmarked roads: These will probably be very twisty and narrow. They might only be wide enough for one car. Sometimes there are few signposts, so it can be easy to get lost. Some do not have a hard surface.

ARENA

The entire story takes place along this dual carriageway.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

The narrator drives a BMW 3.3. li and is very proud of it. This model was released released for sale in January of 1974 and marketed for its torque. It technically has no more power than the 3.0 Si, but BMW told customers it was more powerful because of various modifications. This model had a different feel rather than more grunt, appealing to customers who wanted a luxury car but who weren’t especially interested in driving a sports car.

Because the 1974 model technically had no extra power, and because ‘power’ is the main metric by which rev heads measure a car’s worth, I can imagine there was much talk among car enthusiasts around this time regarding whether the January 1974 model really was ‘faster’ then the earlier BMWs, or whether owners of the 1974 BMW had been victims of a marketing gimmick. It makes sense that the ‘fingersmith’ of Dahl’s story would be skeptical of such a marketing claim, as a professional hoodwinker himself.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

In the wider world of the story, London was — and remains — notorious for its proliferation of professional pickpockets.

These days, Westminster is the favourite spot of pickpockets by far. I read that in a New Zealand article aimed at Kiwis visiting as tourists. As a Kiwi myself who spent about a year living in London, I’m familiar with the naivety of fellow Kiwis. (I would say that Australians are even less accustomed to thieves, however — while Australia has more violent crime, New Zealand has more petty thieving crimes than Australia does.)

When my mother waited in the crowds outside Westminster for the changing of the guards, police officers instructed her to take off her backpack and hold it in front of her. “You won’t even know they’ve robbed you,” she was told. “Many of them are children.”

If you are coming to watch, please do take care of your personal possessions at all times as, like many crowded places, pickpockets have been known to operate in this area.

Changing of the Guards website (downplaying it slightly, I feel)

I managed not to get robbed while living in London myself. But while a group of expat friends drank coffee at Kensington Starbucks, one of my friends did have her purse stolen from right next to her chair. Looking back, I realise it was the mother with the toddler in the pram who just so happened to drop something right next to my friends as we were laughing at a photo on someone’s phone. If we’d been savvy born-and-bred Londoners, we might have deduced exactly what she was up to. But I’m sure she heard our accents and figured she was safe. (Our friend was impressively chill about the whole thing. We went to the police station afterwards and lodged a fruitless report.)

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE HITCH-HIKER”

SHORTCOMING

The narrator is a little too susceptible to peer pressure, a little too keen to show off his new car. Mostly he wants to prove that he hasn’t been hoodwinked by the people who market BMWs.

DESIRE

The narrator is taking his wife’s ring to the jeweller’s in London to get a stone fixed, though I suspect the trip to the jeweller’s is not the point. He will have jumped at the opportunity to go for a nice long drive in his new car.

OPPONENT

False opponent

Rats are untrustworthy animal archetypes in fiction, so by comparing the hitch-hiker to a rat, Roald Dahl encourages readers to remain suspicious. Rats are known to be evasive. Sure enough, this guy is evasive when it comes to answering questions about himself. He may also be a bit of a trickster. Did he trick the rich narrator into getting that speeding ticket? No, as it turns out, but the reader wonders. Dahl sagely anticipates us wondering exactly that, and lampshades it by having the narrator ask the hitch-hiker directly himself.

The hitch-hiker, who has no doubt given the cop a false name as well as a false occupation, does not appreciate the term ‘pickpocket’ when applied to competent magicians such as himself. Comically, he calls himself a ‘fingersmith’, riffing on legitimate trade workers on the ‘right’ side of the law cf. blacksmith, coppersmith, gunsmith. (Most smith jobs no longer exist, linking the hitch-hiker to characters from antiquity.)

THE MEANING OF SKILLED LABOUR

The ‘fingersmith’ label is clearly an attempt to elevate the hitch-hiker’s own status. Dahl could be encouraging readers to reconsider what we call ‘skilled’ versus ‘unskilled’ labour. But another sort of reader might also read this as laughable, in which case Dahl is mocking unskilled workers who comically overstate their own importance in the world. The way Dahl has written this, I think it could easily go both ways.

Note that the 1970s marked a turn towards increasing specialisation in the workplace. This is when white collar job titles started to baffle the working class, because many of them were to do with computers. These days we’re used to hearing someone’s profession and having absolutely no idea what they actually do (my spouse has one such job), but working class men of Roald Dahl’s generation were often very skeptical that there was any need for such jobs at all. (“If I don’t understand it, it’s not a real job.”) This attitude didn’t come from nowhere, as many labourers were starting to find themselves unemployed and unemployable.

The 1970s also gave rise to many new jobs in middle-management, which sounded equally bullsh!tty to anyone below and above. The American film Office Space (1999) makes fun of middle management while also extending sympathy — if you’ve been promoted into a job which doesn’t exist, or exists only temporarily for a very specific purpose, you’re now part of a new precariat.

The hitch-hiker is not happy with the pejorative connotation given by outsiders to his profession.

THE EUPHEMISM TREADMILL

Frequently, over time, euphemisms themselves become taboo words, through the linguistic process of semantic change known as pejoration, which University of Oregon linguist Sharon Henderson Taylor dubbed the “euphemism cycle” in 1974, also frequently referred to as the “euphemism treadmill“.

Wikipedia

Nonetheless, ‘pickpocketing’ remains the legal term:

“Pickpocketing covers theft of items directly from the victim, but without the use of physical force and so easily accessible items like mobile phones and wallets tend to be the most targeted,” Nick Titchener, criminal defence solicitor at London law firm Lawtons Solicitors, said in a statement.

Travellers Warned as Thefts in London Underground More Than Double

Hate sink character

Our hate sink character is the traffic officer — an easy sell, since few people enjoy being pulled over for speeding, even when we know we are fully culpable. This cop is far more annoying than any I’ve encountered myself (mostly encountered for breath tests rather than for speeding fines, thanks for wondering).

One particularly annoying thing this traffic cop does: He asks a series of rhetorical questions each of which only have one answer.

“Perhaps there’s a woman in the back having a baby and you’re rushing her to hospital? Is that it?”

“No, officer.”

“Or perhaps your house is on fire and you’re dashing home to rescue the family from upstairs?” His voice was dangerously soft and mocking.

“My house isn’t on fire, officer.”

“The Hitch-hiker” by Roald Dahl

In this way, he leads the narrator through a conversation which is not a conversation at all, but is purely a shaming exercise. If you’ve ever had this done to you, you’ll know exactly how annoying it is. If you’d like to be equally annoying in return, point it out when you see it. It’s called ‘epiplexis’.

It’s worth understanding how language is not just used to convey information, but deployed in ways which retain and illuminate power structures. If your CEO says, “My pen just ran out,” someone will get up from the meeting to fetch him a new one, but if your seven-year-old at home says the same, you’ll tell him to fetch a fresh pen himself. The same words are interpreted differently depending on how much power the speaker has in comparison to the listener.

Likewise, when writing fictional dialogue, writers can illuminate power structures. Dahl tends to make much use of power differentials and subtexts. In “The Hitch-hiker” the technique is made super obvious, to the point where the traffic officer is mocked.

PLAN

The narrator drives the car, but the hitch-hiker drives the plot.

The hitch-hiker reveals that he’s going to Epsom Downs (in Surrey) to the races for Derby Day Festival (and eventually reveals why).

This event is notorious for its pickpocketers, as Westminster is to this day.

As evidence, I offer you this Victorian (1856) painting by William Powell Frith, who attended Derby Day not to gamble but to make character studies. (This event has been held since 1627.) Look closely at the painting and you’ll find a young man checking his empty pockets, the victim of a thief. With big winnings, wealthy people and plenty of liquor flowing, this would be one of the main pickpocketing events of the year for a pickpocket.

I have a wager of my own: The rat-faced hitch-hiker would have thieved from the driver had the driver proved unpleasant, condescending or otherwise disagreeable to him. But because the narrator rose to the hitch-hiker’s challenge, these two men showed they were on the same level, despite their apparently socioeconomic disparities.

On the topic of socioeconomic ‘disparities’, who knows how much wealth this rat-faced guy has really accumulated, though. He may be a fairytale troll with a cave of treasure somewhere in the woods.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Makes sense that cops would be lining the highway. They’re about to catch a whole lot of drunk gamblers this afternoon, attempting to drive home.

When the hitch-hiker gets his driver into trouble for speeding he knows exactly how to get out of it. But rather than reassure the narrator directly, he takes the opportunity to show off his prowess.

Roald Dahl stories are heavily populated by men who are one-upping each other in passive-aggressive ways. In “The Ratcatcher“, part of the humour derives from the narrator having none of that. The two men who are not ratcatchers simply want the rats caught. Then they plan to move on with their lives. But the rat-faced ratcatcher in that story is hellbent on showing how canny he is. He’ll go to disgusting extremes in pursuit of one-upping the other men. The rat-faced hitch-hiker is similar in that he clearly comes from a class of people who are routinely dismissed.

ANAGNORISIS

In this genre of story — based on the tall story — the main character doesn’t have any great epiphany about how they should be living their life. Instead, we’ve got a twist, or a reversal.

First Dahl gives us hermeneutical closure: We learn what it is this hitch-hiker does for a living, and why he is going to the races. (It is part of the social contract that a hitch-hiker will offer company to the driver, or even better, entertain. This hitch-hiker has done just that by turning his identity into a puzzle, and showcasing his skills like a magician.)

Next we get what film-makers call a ‘reversal’. The hitch-hiker is set up to pull a fast one on the driver. We half expect the driver to say goodbye to his hitch-hiker than discover his gold watch is gone. But no, it turns out the hitch-hiker is an ally after all, not an opponent, and his magic has saved the day. A reversal is a little different from a ‘twist’. A twist describes any unexpected ending, whereas a reversal causes us to revise what we originally thought was happening. In this case, opponent turns ally.

NEW SITUATION

The narrator initially stopped for the hitch-hiker because despite having found wealth himself, he has not forgotten what it’s like to be in need of a ride. He does not wish to be one of those rich bastards poor people despise. Counter to the stereotype of a BMW owner, this guy does not look down on the hitch-hiker.

For his moral goodness, our narrator has been rewarded. He has this (temporary) new friend who is on his side.

The moral is an old one. We can even find it in the Bible: “love your enemies, and do good, and lend, expecting nothing in return, and your reward will be great, and you will be sons of the Most High, for he is kind to the ungrateful and the evil.”

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

It’s unlikely the narrator ever sees this particular pickpocketing hitch-hiker again. I feel the pickpocket has only revealed himself because he needs a lift. I doubt anyone sees him normally, in this example of borderline magical realism. The rat-faced guy is invisible to humans, much like the animal.

Then again, this hitch-hiker is not the only part-rat character in Dahl’s oeuvre, which suggests an entire underclass of English people who are part-human, part-rat. They do the work no one else wants to do: rat-catching, manual labour, jobs to do with death, jobs to do with slaughtering. Since these people wouldn’t want to do these jobs any more than the rest of society, it makes sense that this fellow has decided to hone skills only useful when living on the flip side of the law.

England does have an underclass of people with a history of discrimination. We see in British children’s literature how the Romani have been regarded over the years. In various other countries live so-called ‘untouchable‘ people — mostly found in South Asia e.g. the Dalit. Less well-known are the Burakumin of Japan.

When the traffic officer in Dahl’s story threatens the passenger because he doesn’t like the way he looks, this is best read as an allegory for racism. In Jordan Peele’s Get Out, the Black passenger of a car is threatened by a traffic officer even though he wasn’t driving.

I do wonder if Dahl’s part-rat characters might be ‘g*psy’ archetypes, especially because these characters travel from place to place, are impossible to locate in any one spot and are thereby considered suspicious.

RESONANCE

Modern cars are remarkably reliable, but having your car break down was a far more common experience in the 1970s and earlier. It would happen at some point to any sort of person driving any sort of car.

If you see someone hitch-hiking these days, there’s likely a story behind the scenario other than ‘my car broke down’ and I feel this has affected the sorts of narratives which include hitch-hiking characters.

Here is my short story about a hitch-hiker, set in New Zealand. It’s a non-supernatural riff on the Vanishing Hitch-hiker urban legend.