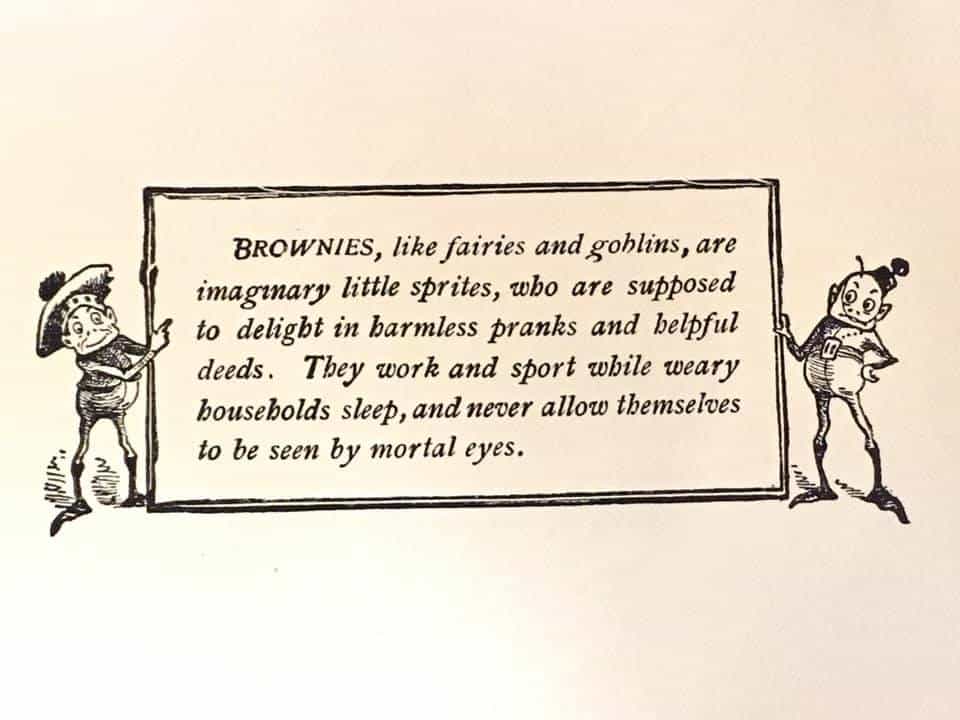

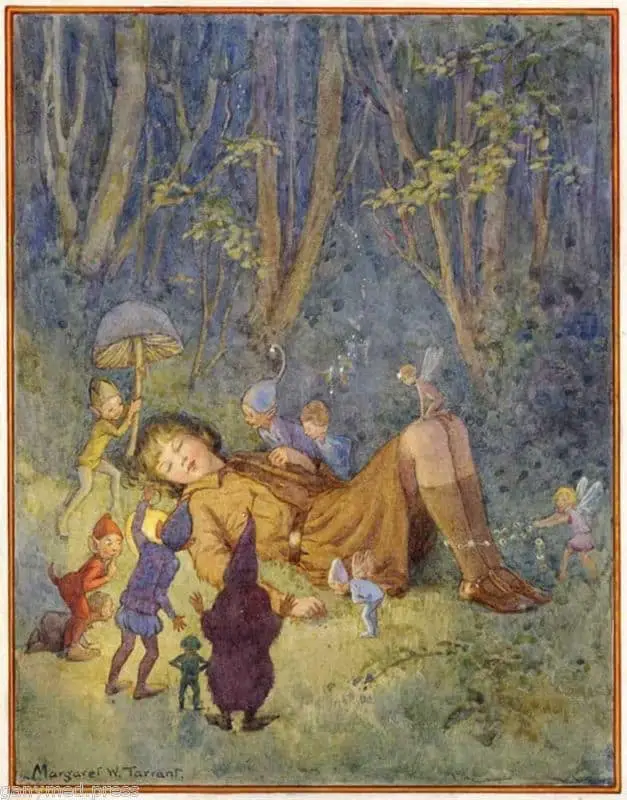

A brownie is a fairy from English and Scottish folklore.

They live in houses (so are a type of hobgoblin — ‘hob’ referring to the cooking equipment with hot plates).

They are industrious.

Like German poltergeists, they sometimes mess up the joint. This is done out of mischief rather than malice.

However, the Yorkshire boggarts and bogles of Scotland are malicious, no different in their behaviour from poltergeists.

If you hear soimething at night, it might be a brownie cleaning your house. (I guess mischievous brownies like to mess things up because they like cleaning so much.)

They are offended by gifts left out for them, except for bread and milk/cream, which they love. Leave it by the hearth. (The hearth is considered a liminal space in a house, where fairies can get in.) The tradition of leaving cookies and milk out for Santa (a sanctified chimney demon) is clearly descended from brownie folklore.

They’re similar to the Scandinavian tomte in that they keep watch over the farmstead at night. (Though I’m not sure if brownies are thought to peer in through windows and keep watch over children.)

A puck is similar to a brownie. In old Middle English the word ‘puck’ meant ‘demon’. Fast forward to Elizabethan times (1558 – 1603) and pucks are more fairy than demon, indisguishable from hobgoblins/brownies. You may know the character of a ‘puck’ from A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1595/96) by William Shakespeare. Written near the end of the Elizabethan era, Shakespeare’s Puck is of course an Elizabethan archetype, mischievous rather than ‘demonic’.

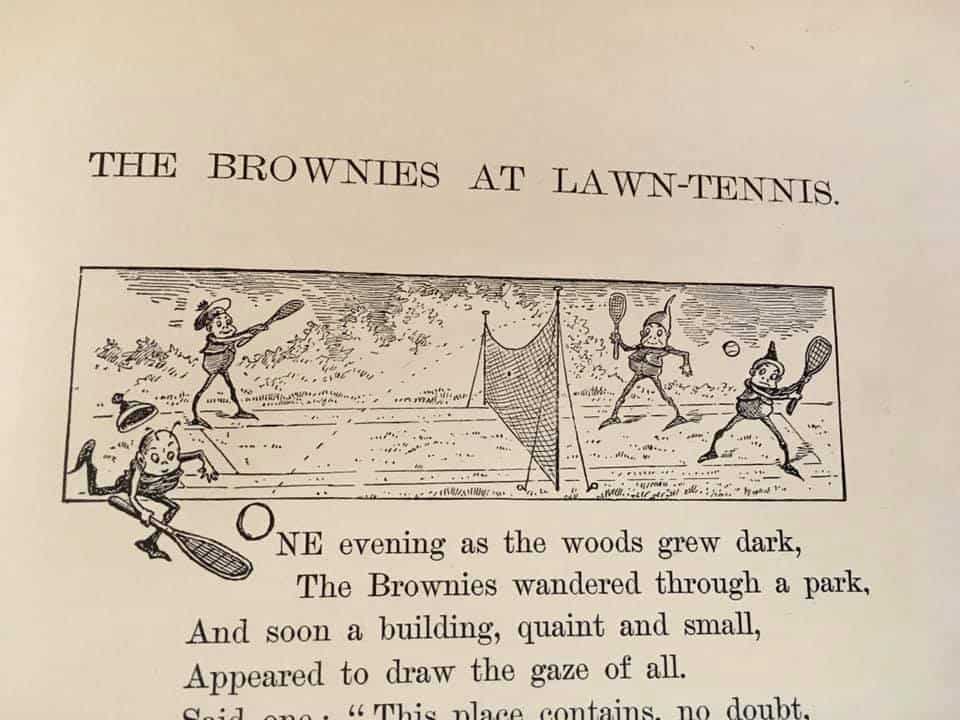

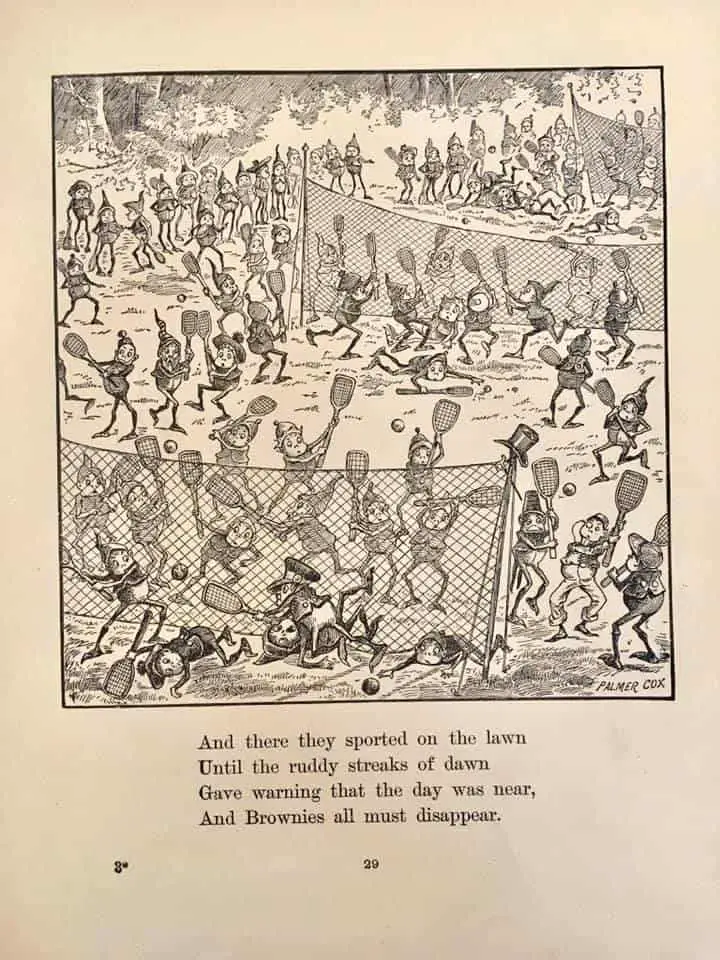

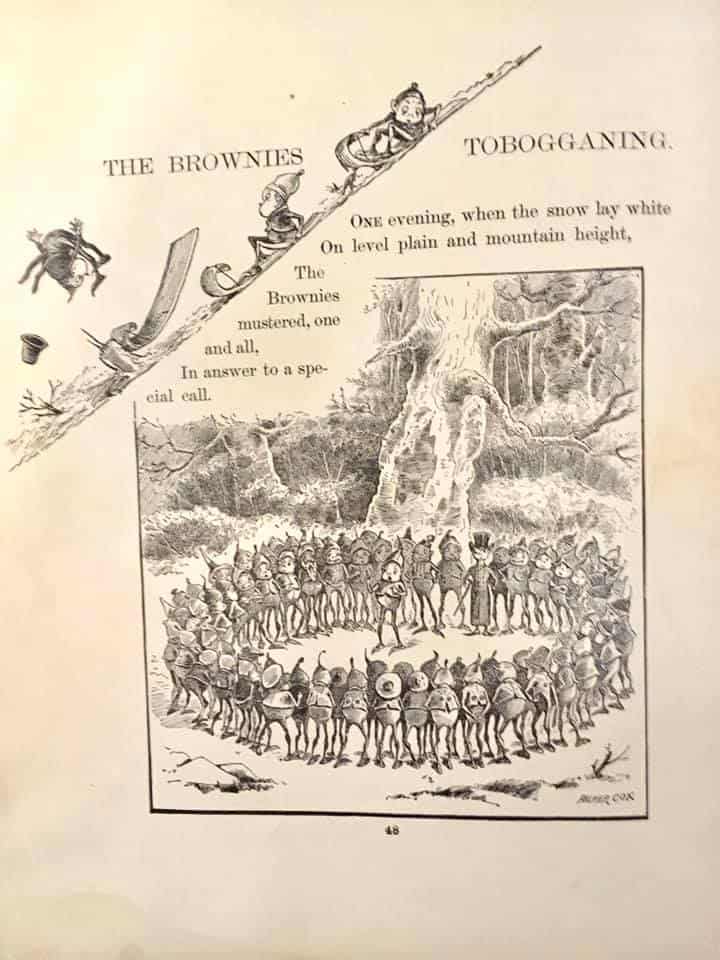

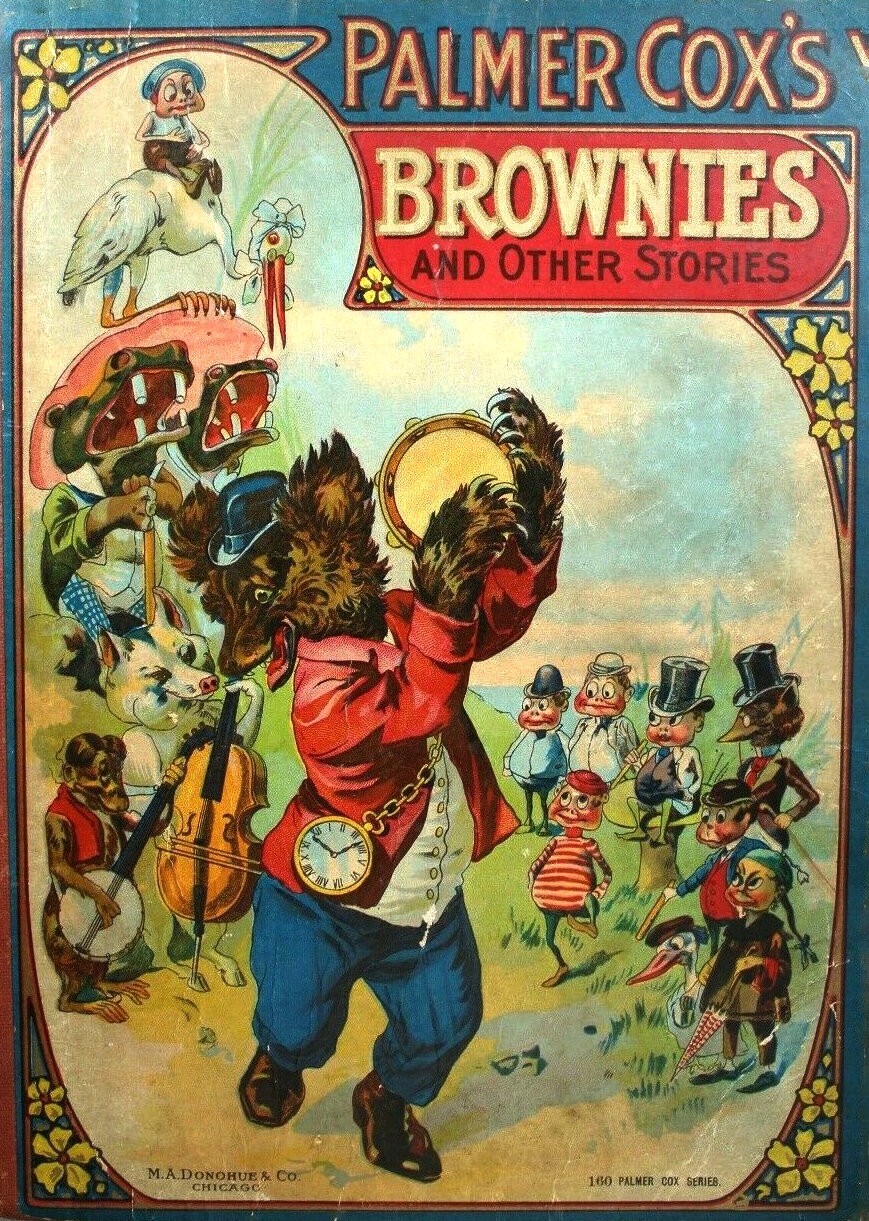

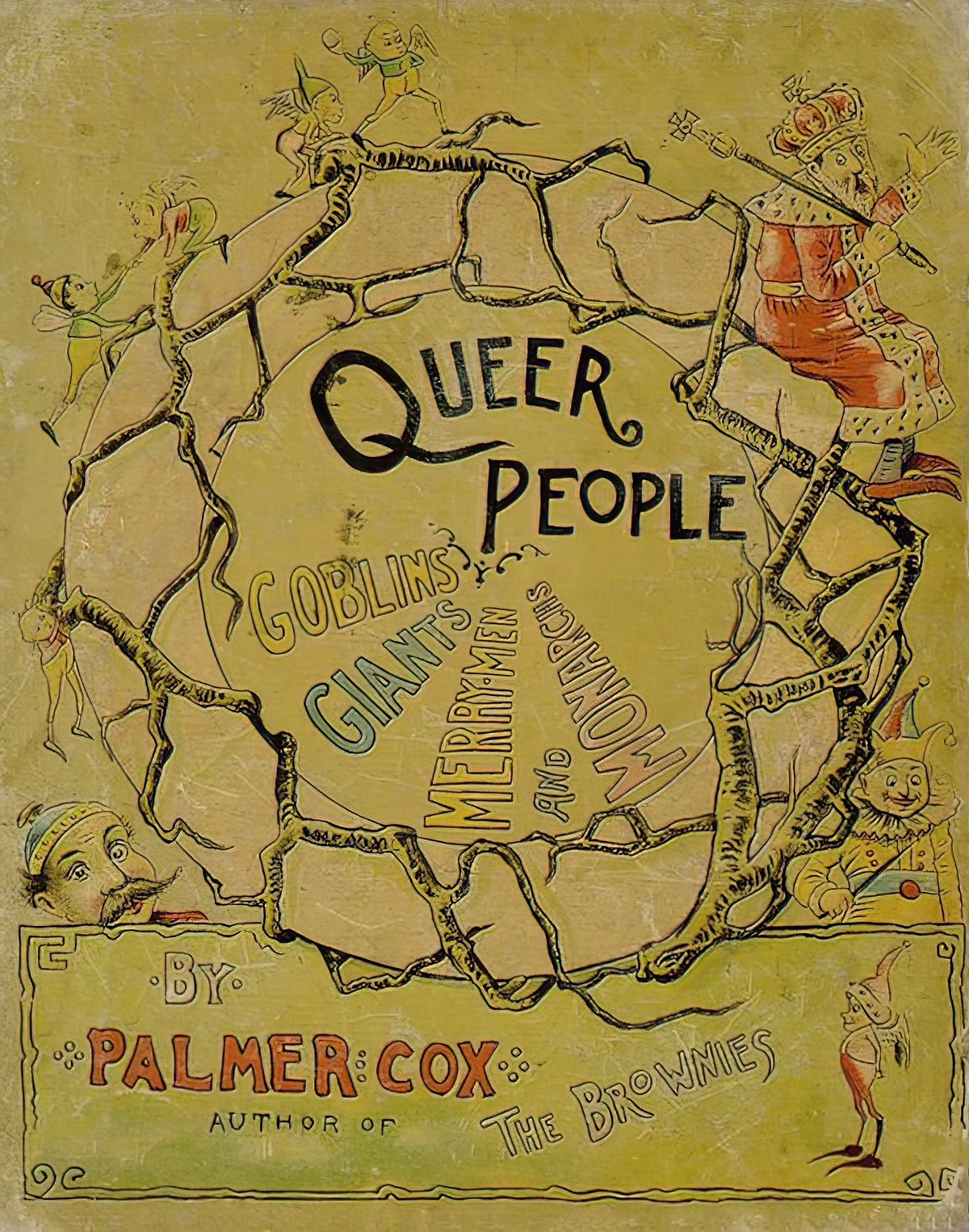

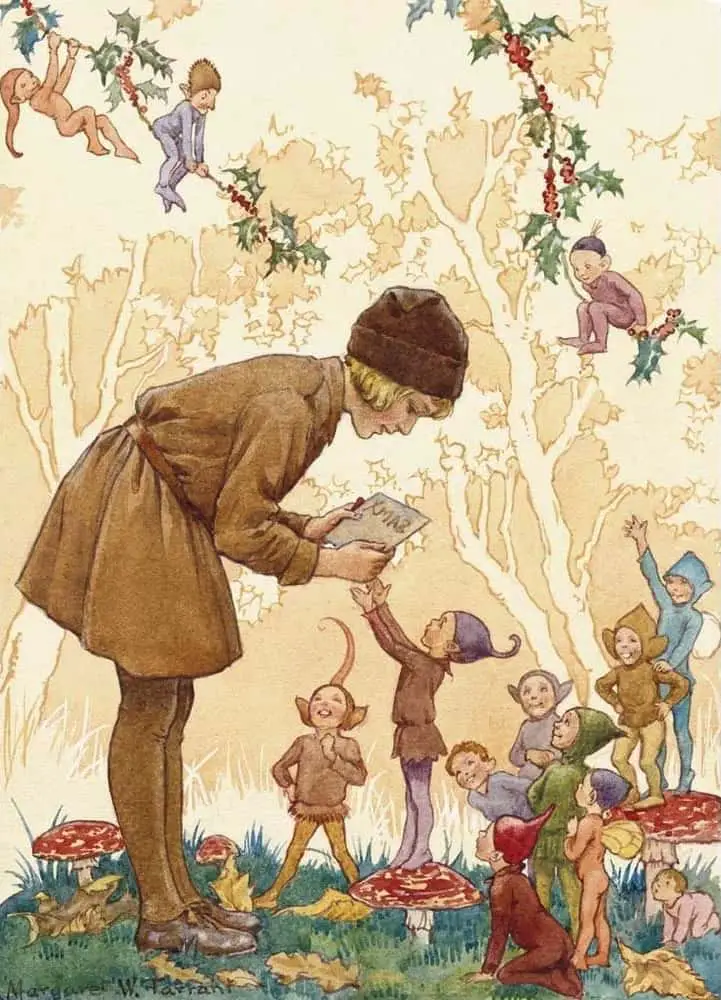

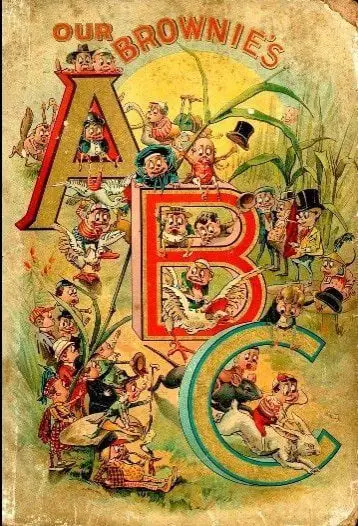

Brownies endured in UK folklore as mischievous creatures with childlike qualities. Naturally, when the phenemonon of ‘literature for children’ emerged, brownies were perfect as characters in children’s books. The Golden Age of Brownies began in the late 1800s. A guy called Palmer Cox led the charge.

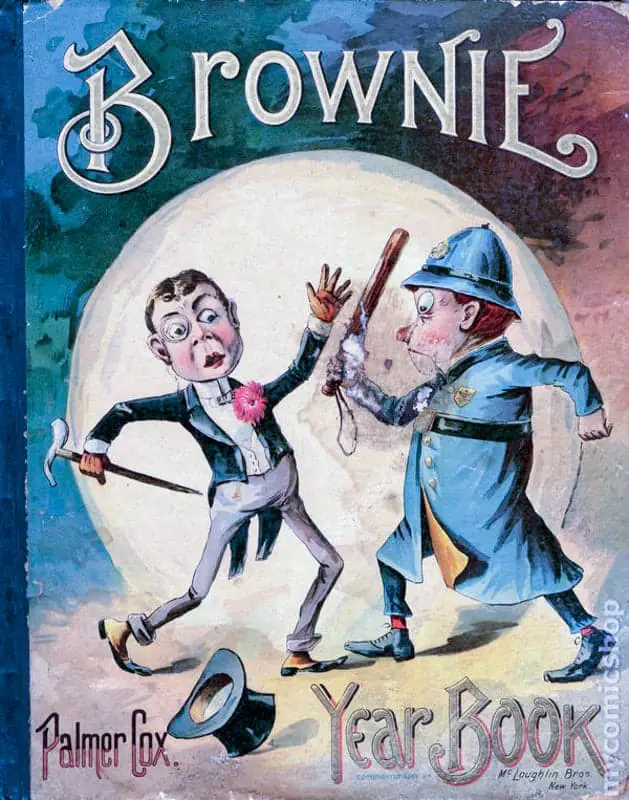

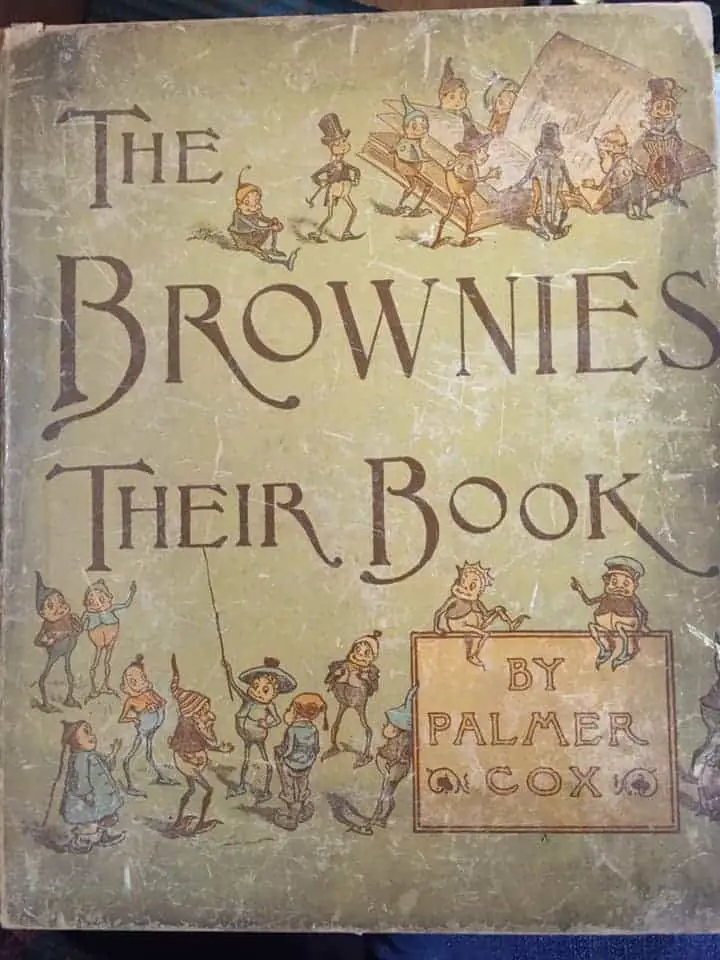

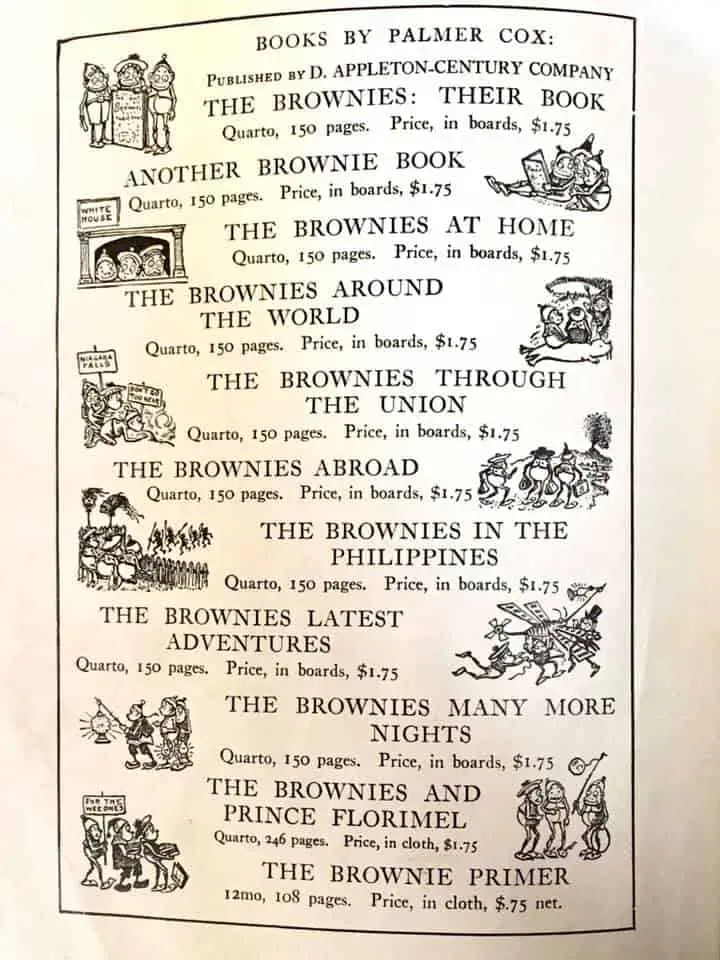

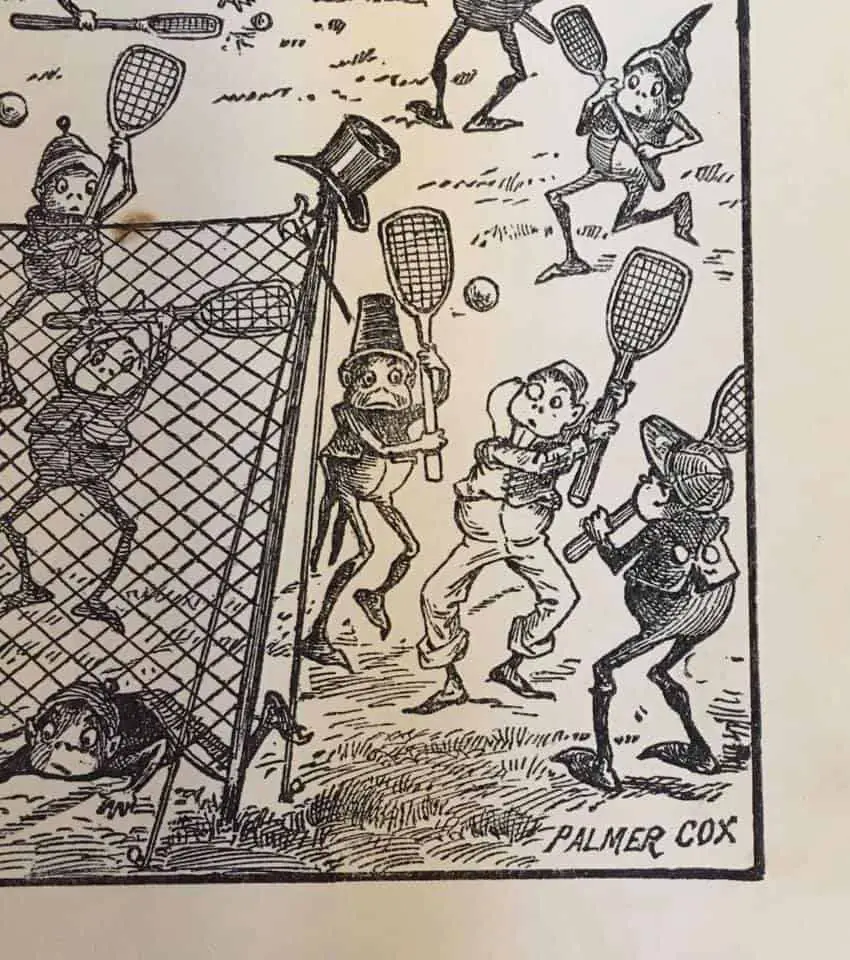

Palmer Cox (1840 – 1924) was a Canadian illustrator and author. He wrote a series of funny rhyme called The Brownies. These are thought to be some of the first comic books. The cartoons were published in several books, such as The Brownies and Their Book (1887). One of the earliest cameras purchased by consumers was called the box brownie, apparently inspired by Palmer Cox’s stories.

How big are brownies? In The Brownies and Prince Florimel, Palmer Cox said they were the size of twelve-year-olds, but in other stories he shrinks them right down. Basically, fairies can be as big or as small as a story requires. Take a fairytale such as Snow White and Rose Red: The dwarf in that story seems to increase and decrease in size as fits the scene. Brownies are no different, though I had never thought they were as big as twelve-year-olds. (I saw a large group of twelve-year-olds last week — some are the size of adults, others the size of children.)

Palmer Cox encoded another significant change to popular conception of brownies: Beforehand they had been considered solitary creatures. But Cox’s brownies hang out in large mobs, more like today’s Minions. In the wild, solitary creatures are the most formidable: You don’t want to meet a male grizzly, for instance. By giving these creatures lots of friends he gave them a party vibe, and now they were properly bowdlerised. Despite being called Brownies, these are folkloric brownies in name only. They are now basically pixies.

Another influential person in the Golden Age Of Brownies was Julia Horatia Ewing. In 1870 she wrote a short story called “The Brownies”. (She was only 23 at the time.) Although brownie stories were common in oral folklore, this is one of the first written works to feature brownies.

As far as their gendering goes, big mobs of Cox brownies are kind of like Smurfs: We are to use the masculine pronoun, while also considering them ‘gender-free’. (A linguist’s commentary on that.) Cox describes the brownies as age-less and super beautiful — virtues more traditionally associated with idealised femininity.

Their loveliness of face and form was beyond all description. Just try to think of the prettiest girl you ever saw. Well, even the plainest of these fairies were ever so much prettier.

The Brownies and Prince Florimel

Instead of a patriarchal Papa Smurf, Cox’s brownies are ruled by Queen Titania.

ENID BLYTON

I grew up reading Enid Blyton’s stories, which were already old by the time I got to them. Influenced by Cox’s version of Brownies, Blyton’s ‘brownies’ are basically pixies. These creatures make for excellent main characters in stories because audiences love tricksters.

C.S. LEWIS

When creating his Chronicles of Narnia, C.S. Lewis utilised pretty much every folkloric character he’d ever encountered and smooshed them together in a bizarre creation which somehow, for some reason, worked. Lewis’s brownies are more similar to the folkloric kind — hobgoblins who stay in the house and do your housework.

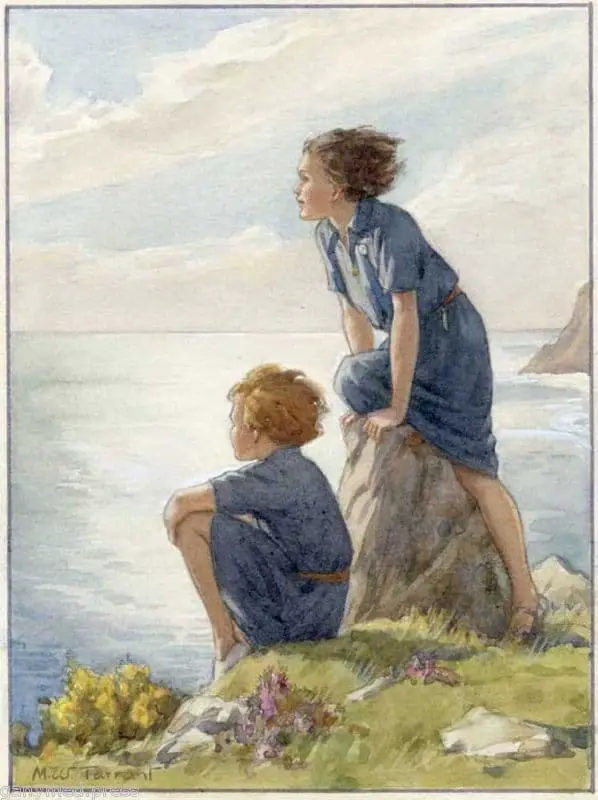

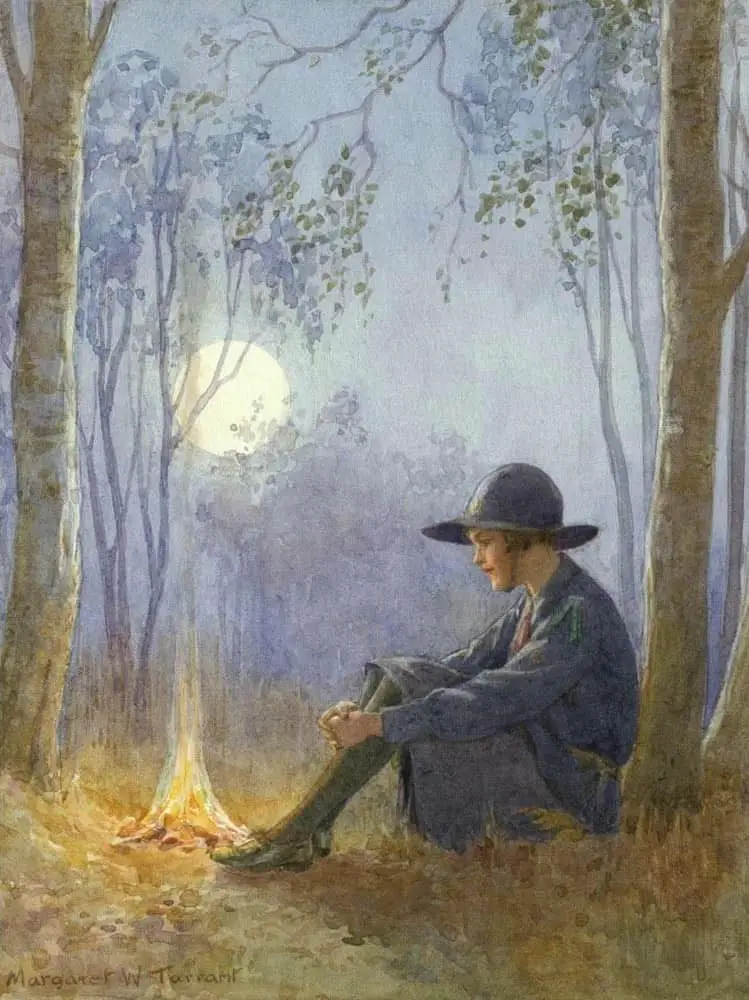

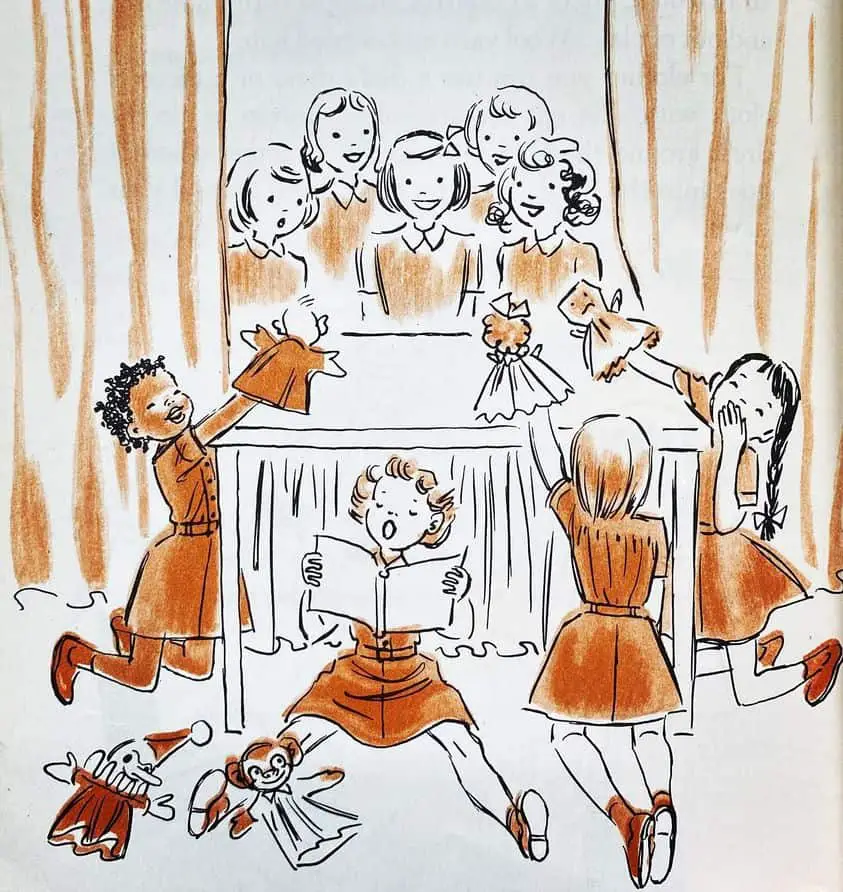

THE GUIDES (BROWNIES)

Settling upon a name for the younger (formally Girl) Guides has proven problematic. At first the 7-10 year olds were called ‘Rosebuds’. Lord Baden Powell listened to the girls who complained that they did not like this name. He decided to rename the younger girls Brownies after Julia Horatia Ewing’s short story. Younger Guides were called Brownies until 1996. Now, Guides of all ages are simply called Guides.

It makes sense that Baden Powell renamed 20th century guides after folkloric brownies. Like archetypal little-mothers, brownies are homebound, industrious and always cleaning up after people. It may have felt somewhat progressive to name girls after brownies, because brownies are also mischievous and enjoy a degree of self-determination. Reading the story today, I wonder if “The Brownies” was ever enjoyed by children. Like the vast majority of Victorian writers for children, Ewing wasn’t really interested in entertaining children. She was teaching them to be helpful and submissive.

Although we no longer call the younger guides ‘Brownies’, the phrase ‘Brownie points’ remains in common English usage. This originally referred to the merit badges (or six points) earned by Brownies for carrying out good deeds.

BROWNIES IN CONTEMPORARY CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

I don’t know for sure what prompted the Guides’ shift away from the word ‘brownie’ in the mid 1990s, but I feel it is indicative of a shift in the associations we have with the word. Few kids grow up with stories about folkloric (pixie-like) brownies anymore. Do an Internet search and the brownie is more commonly associated with a chocolate-y baked good. Even J.K. Rowling, who has certainly done her bit to keep old folkloric characters alive for younger generations of readers, has ensured brownies go the way of baked goods:

The brownie is a flat, baked square or bar sliced from a type of dense chocolate cake, which is, in texture, like a cross between a cake and a cookie, and is made by the Hogwarts kitchen House-elves .

The Harry Potter Wiki

As you can see, Rowling does utilise the folklore of the brownie; she simply does not call them ‘brownies’. She calls them house-elves, and she also rounds out their characters.

Aside from the baked goods, there’s also the ‘drop a brownie in your pants’ association, as well as offensive ones. This may have contributed to the demise of the children’s book brownie, whose Golden Age has long since gone, but who remains with us, mostly under different guises. A bestselling exception is The Spiderwick Chronicles by Holly Black and Toni diTerlizzi, with standout brownie creature called Thimbletack.

Header: Palmer Cox (1840 – 1924) for The Brownie Year Book 1895