“The Fly” is a short story by Katherine Mansfield, published 1922.

CONNECTION TO MANSFIELD’S OWN LIFE

Mansfield wrote “The Fly” in February 1922 as she was finding her tuberculosis treatment debilitating. She died in January of 1923, soon after its publication. Thirty-four seems young to be contemplating old age, and to write about an elderly character with any sort of gravitas, but it’s likely Mansfield always had empathy for the elderly. She had probably sensed she would die young. For one thing, she’d faced plague. The Beauchamp family escaped central Wellington to live in Karori, probably to evade the bacterial infections which were highly dangerous to Wellingtonians at the turn of the 20th century. Aside from that, Mansfield grew up with weak lungs. The family doctor told her family (if not Mansfield herself?) that she was a case of tuberculosis waiting to happen.

By the time Mansfield actually did succumb to tuberculosis, I wonder how she had processed the concept of ‘inevitability’. The modern-day analogue is a person who knows they carry genes which put them in the firing line for future health problems and a likely early death (e.g. for breast cancer, Huntingdons, early onset Alzheimers). The more we learn about genetics, the more all of us will be expected to either confront death (by paying for gene sequencing, say), or to ignore it completely (like The Boss in this story). How much should we mull over our own deaths? What is the perfect amount of death-mulling in order to live a good life? This is the ultimate moral dilemma for privileged people of the modern age.

We can only read her stories and speculate about how Mansfield lived with ill-health, but putting her writing to one side, she did live life to the fullest, perhaps because she was always under the spectre of death.

When facing death, it’s common for people to readjust our sense of scale. Big things seem smaller (we realise we are not invincible). Important events are cast as freshly irrelevant. The flip side is that small lives become more meaningful: A fly can lose its life just like that. And we’re no different. Everything feels more connected. (Users of psilocybin will tell you of similar experiences, without necessarily facing their own mortality.)

This is partly why imagery surrounding ‘miniatures‘ is so commonly utilised by storytellers. You can make the argument that all stories are about life, and therefore all stories are about death.

What Happens In “The Fly”?

Old Woodifield is an elderly man who goes to visit his former boss at the boss’s office. He’s impressed that the boss is still doing well in the workplace, even though he’s a full five years older than himself.

Old Woodifield forgets what he came to say, but after a tipple of whiskey (which his health properly forbids), he remembers: His daughters visited France recently, including the graves at Flanders Fields, where both old men lost sons.

Old Woodifield tells his boss that they also found the boss’s son’s grave, and would like to reassure him the grave is very well kept. Then Woodifield leaves, unaware of how he has plunged his former boss into the depths of despair.

The reader stays in the room and we watch on as The Boss slowly kills a fly entrapped in his ink pot.

Setting of “The Fly”

The story is set in the post-WW1 era, near London. “The City” is capitalised, so refers to “The City” district of central London. France is revealed to be a foreign country with very foreign customs when Old Woodifield offers the anecdote about paying for the entire jar of jam. (There is an historic cultural juxtaposition between England and France.)

Some of the language indicates its era:

- “Toss off” now means something else entirely, but back then meant to ‘down’ a drink.

- ‘Wiped his moustaches’ — this word has evolved in the opposite direction of trousers (which were once considered plural, now considered singular, often called ‘trouser’).

- ‘Chaps’ now refers almost exclusively to the butt-less leather trousers. Back then the word referred to the same leggings and belt, but not in place of butt-covering attire. The word was pronounced ‘shaps’, fyi.

Narration In “The Fly”

This story is told with omniscient narration, neither entering too far into the mind of the boss nor Mr Woodifield.

“The Fly” is typical of Mansfield’s storytelling technique: The reader is moved through a series of incidents, carried along with the action. Eventually the reader discovers causal relationships. Honeymoon, The Voyage and Prelude make use of the same narrative technique.

Character Web of “The Fly”

The Boss

As first presented, the Boss appears to be the archetypal godlike figure, giving life and taking it away. The Boss is given no name—he is known simply as ‘Boss’—authority, father figure to both Woodifield and to Macey.

It’s interesting to look at how ‘Boss’ is used today in modern language to mean ‘Some challenge you just can’t defeat’ e.g. in a tweet I saw very recently: ‘For trans girls eyebrows are the ultimate boss’. (I figure this usage comes from gaming?)

In any case, Mansfield is widening the usage of ‘Boss’ decades before gaming existed. In “The Fly”, this Boss character gives a little drop of whiskey to Woodifield, insisting it wouldn’t hurt a child, even though alcohol is forbidden to the old man. This interaction is very reminiscent of a scene in Annie Proulx’s much later short story “On The Antler“, though in Proulx’s story the alcohol is literally poisoned. (To someone who can’t drink for health reasons, alcohol on its own can be poison.)

The Boss character is also set up as materialistic. Mansfield both shows and tells us this fact.

[SHOWING] ‘New carpet,’ and he pointed to the bright red carpet with a pattern of large white rings. ‘New furniture,’ and he nodded towards the massive bookcase and the table with legs like twisted treacle. ‘Electric heating!’ He waved almost exultantly towards the five transparent, pearly sausages glowing so softly in the tilted copper pan.

[TELLING] But he did not draw old Woodifield’s attention to the photograph over the table of a grave-looking boy in uniform standing in one of those spectral photographers’ parks with photographers’ storm-clouds behind him. It was not new. It had been there for over six years.

Some critics have said this indicates an earlier, less polished time in Mansfield’s writing development because succinctness is highly prized. However, I’m not on board with that view. I think succinctness can be too highly prized. Like any other kind of emphasis, emphasis achieved by both showing and telling is acceptable to me as a reader. (Might showing and telling even be considered a form of parallax, at a micro level?)

More interesting: Why did Mansfield want to underscore this facet of The Boss’s personality?

- Materialistic characters are non-empathetic characters. That’s a rule.

- He’s also a braggart. A rich, powerful man who is also a braggart is the worst kind of rich, powerful man.

- But he is also pitiable in his own strange way. Braggarts are showing their shortcoming: They’re not as confident as they hope to appear. A man who brags about his possessions is making up for something very weak about himself. The reader draws this conclusion early (subconsciously, if nothing else) and so when we see his actions at the end, the ending is both surprising and expected. (The rule for endings.)

- On second reading (or in hindsight) we understand that by fixating on objects, The Boss can avoid thinking about death. Objects cannot die. Flies can die. Flies are not objects. But he seems to consider the fly a kind of object, as a part of the room itself, until he is hit by its tiny death.

I conclude that Mansfield had good reason to underscore the materialistic views of The Boss.

The Boss’s Son

We don’t know what the son was really like because we’re viewing him from the father’s point of view. Bereft family members have a tendency to remember only the best of the dearly departed. It’s highly likely the son wasn’t anything like the angel he remains in his father’s memory.

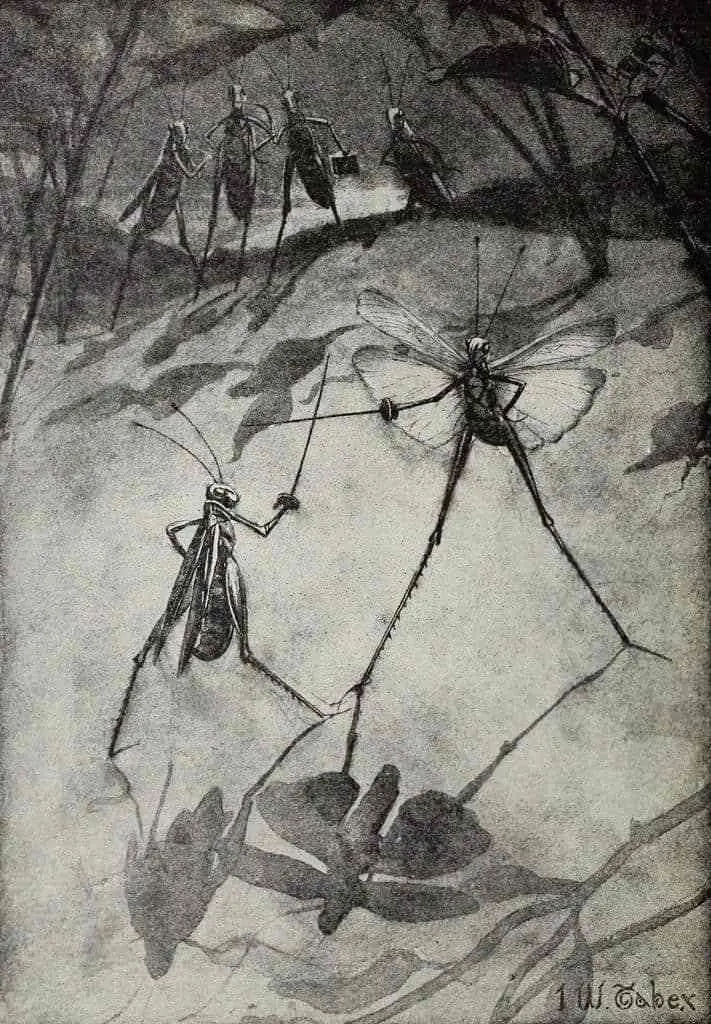

This is from a completely different book, published in the late 1800s. I thought of the father and son from Katherine Mansfield’s short story “The Fly”.

Also possible: The Boss required the son to come and work for him whether son wanted to or not, and The Boss refused to listen to anything else. It’s possible The Boss has sociopathic tendencies. While most neurotypical people think nothing of killing a fly, I think most of us prefer a swift and painless death for any living creature.

Like many parents, The Boss had hoped to achieve immortality via his son. Losing his only son means losing his own sense of immortality.

The Fly

When the Boss begins to play with the fly, birth imagery appears and readers remembers that Woodifield was described as a baby. As the fly struggles to recover from the persistent blobs of ink The Boss drops on him, readers understand that the fly is a symbol for humanity and the fly’s struggle is the struggle of humankind.

Stating the obvious: Flies also ‘fly’. Katherine Mansfield is making use of The Symbolism of Flight. Flies can soar through the heavens and perhaps they have lots of fun, escaping any kind of earth-bound reality. But flies die in the end. Alongside us, flies endure an ordinary and inevitable lifecycle: birth, youth, ‘old age’ (for a fly), death. There is struggle, even for free creatures.

But along with the struggle there are moments of flight, desires, hopes, aspirations. If we put ourselves in the fly’s position, it probably thinks it can get away, until the deathly amount of ink is dropped upon it.

Old Woodifield

Where did Katherine Mansfield come down on the Freudian concept of repression? Old Woodifield has repressed nothing. But look at him. He’s five years younger than The Boss, already retired, his health is at the point where he can’t take whiskey and he seems to be losing his memory, possibly hastened by the stroke which caused his retirement. He is now under the care of his wife and daughters.

We can’t apply a cause and effect analysis to how humans age in real life, but we’re talking about fiction here. Could it be that in “The Fly”, Old Woodfield’s openness towards mortality has actually hastened his own?

Helen Garner wrote a novel called The Spare Room, in which a woman is cast into the reluctant role of caregiver when a friend comes to stay. The friend is undergoing cancer treatment. In interviews, Garner has said that ‘denial of one’s impending death’ is one way of dealing with death. Since death comes anyway, there’s no right or wrong way of dealing with it.

My brother, a hospital nurse, also tells me that it is very, very common to be admitted to hospital in the late stages of a deadly illness and still not ‘accept’ death is happening.

One possible reading of “The Fly”: By repressing thoughts of death, we don’t ever have to deal with it. (By the time we’ve dealt with it, we’ll be fully dead., which is not dealing.) In the meantime, keep working, keep busy.

Western governments, spurred on by a rapidly ageing population, probably take The Boss’s view.

Alternate reading: Old Woodifield has ‘Old’ in his name, but is consistently described as a baby. We could look at this both ways: Old people are helpless like babies and there’s your comparison. When Mansfield calls Old Woodifield a baby, she might simply be underscoring his old age. On the other hand, his acceptance of Heidegger’s Being-toward-death makes him immortal, in a way. Once we learn that death is a thing, and that it will eventually come for us, we’re ‘outside’ death. (‘Forever young’, despite all evidence to the contrary.)

Symbol Web of “The Fly”

In the first episode in “The Fly” Woodifield and the Boss are contrasted in using imagistic patterns.

Old Woodifield, though five years younger, is nearing his grave. He’s ‘boxed up‘ and looks ‘like a baby in his pram’ but still likes to go out as ‘he clings’ to his ‘last pleasures as the tree clings to its last leaves’. He ‘pipes’, ‘peers’, has ‘shuffling footsteps’ is frail’ and ‘old’ (stated seventeen times) and ‘on his last pins’.

The Boss, on the other hand, though described in less imagistic language, is still ‘at the helm’, ‘going strong’, rolls in his chair, and ‘flips’ the Financial Times, interested as he is in his business and life. The Boss has a strong lust for life and shows a great capacity to survive. The imagery that defines the environment is remarkably positive, and equally rich in suggestions of the boss’s energy, his strength, warmth and generosity.

Indeed the implication, especially through contrasting comparisons with old Woodifield, is that the Boss has an unaging vitality. He seems to be immune to life’s ravages and this suggests an important theme. The very effect of the description of the room and the boss’s subsequent conversation with Woodifield is to establish a dichotomy between the two men as well as to portray them naturally in a realistic social context.

Mortality, already implied by the contrasting images, is directly conveyed by the striking verbal metaphor of the boss’s son in his grave: ‘It was exactly as though the earth had opened and he had seen the boy lying there with Woodifield’s girls staring down at him’. This momento mori together with his son’s photograph make him forget the six years, although his mental grasp has weakened. But the Boss has built up not only his thriving business but also an effective defence mechanism. There are no tears to shed.

By sheer accident the boss finds a fly in the inkwell and unconsciously picks it out, watching the struggling fly brushing off the ink in order to survive, the Boss finds in its fight for life an analogy with his own will to survive. The introductory, contrasting images have generated a sense of the boss’s zest for life, which is also evident in the action.

Killing the fly he paradoxically wishes it to weather adversity, increasingly identifying himself as the courageous little insect in the animal images: ‘like a minute little cat’, ‘the little beggar’ and ‘he’s a plucky little devil.’ Time and his zest for life ‘(‘for the life of him’) have healed the wound in his heart.

The images reveal the true nature of the Boss and inform and extend the meaning of the action in the short story. With Mansfield’s method of narrative restraint, which eschews expository comments, the boss’s final oblivion is expressed in the referential narrator’s discourse, but the full weight of the boss’s fight for survival is expressed by imagistic patterns.

Julia van Gunsteren, Katherine Mansfield and Literary Impressionism

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE FLY”

SHORTCOMING

The Boss represses his own difficult emotions, pressing reset again and again, which leaves him open to continued small wounds when he least expects them.

The Boss is the archetype of the broken man who wants to embed himself in his work in order to forget other kinds of pain. The men of Mad Men are uniformly of that type. If they were to understand their own difficult emotions, those emotions would absolutely break them.

Short stories are well-known for their epiphanic moments, and for characters who change just a smudge. (There’s little time for massive character arcs.) “The Fly” is an excellent example of minimal character change (if any at all).

DESIRE

The Boss seems quite happy to continue on as Top Dog of his own company, and no doubt enjoys the authority that comes with it. But this was an era in which men did tend to retire at a certain, fixed age.

The Boss hasn’t retired, which suggests he wants to live in the past. Today starts off as many other days must have, no different from how days have looked his whole working life.

I’m filling in gaps, but I imagine The Boss pretends he’s a much younger man, and that his son is also younger, safely ensconced in his school work, or at home with his mother, still alive and still full of promise.

OPPONENT

Old Woodifield is the opponent because in contrast to The Boss, this is an old man who has come to terms with his impending death. (He’s long since retired.) He’s also come to terms with his own son’s death in the war, to the point where he can talk at length about how well the graves are tended. This is a man who has not repressed his grief, or his own fear of death.

When confronted with such a peer, The Boss is asked to confront his own dark emotions. This is the unique trait of a same-aged peer, and why school reunions in particular can be so confronting. We can look at a much older person and separate ourselves from their mortality. We look at much younger people and we consider them almost ageless. But when we look at those the exact same age, we tend to compare ourselves to our peers in every facet—how are we doing in life? How old do we appear to others?

Only our same-aged peers can show us.

In storytelling terms, Old Woodifield is The Boss’s foil.

Foil: A character with behaviour and/or values that contrast those of another character in order to highlight the distinctive temperament of that character.

Foils work best when they’re the same in many ways:

- Same approximate age

- Same milieu

- Same life tragedies

PLAN

You’ll have heard of Save The Cat as a writing technique. (Kill The Dog is its inverse, though Kill The Dog isn’t dissimilar in function: It is used to show an audience the good in a main character.)

Often in a story, a character will save the life of an insect to show the audience how empathetic they are, deep down. This technique was utilised numerous times throughout the coming-of-age film American Honey, for instance. After the main character does something questionable, she is shown to save an insect, until eventually we see her do something really nice for some hungry kids. It’s also utilised in one of the first scenes of Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri, to get us onside with Frances McDormand’s character. Mildred Hayes is presented as a tough nut who may or may not be in the right, insofar as the audience knows, so in the same confrontational opening scene the writer/director has her walk over to the windowsill and flip a beetle back onto its feet.

But in “The Fly”, a man is presented to the reader as your regular Boss (hence the lack of a name — this guy is an archetype). But then, when he sort of tortures a harmless — if annoying — little fly, Mansfield breaks archetype to add a little extra. That little extra is not good. It’s uncomfortable to read and now we definitely don’t like this guy. (Even if we don’t like flies either.) This story represents the true inverse of Save The Cat.

BIG STRUGGLE

The Battle between The Boss and Fly is heavily stacked, and obviously ‘won’ by the Boss, but for him it’ll be a pyrrhic victory, since the death of the fly can only remind him of death in general… his son’s, his own. (And possibly his wife’s as well — in the eras before birth control, an only child often indicated death of a parent, outside secondary infertility.)

ANAGNORISIS

One reading of this short story is that The Boss realises his own mortality for the first time after Old Woodifield’s visit, but I’m not on board with that reading. The final sentence indicates The Boss has had many chances to come to terms with his own mortality (and with the death of his son), but each occasion leads him to repress any uncomfortable grief and…

NEW SITUATION

…he presses the reset button.

For the life of him, he could not remember.

On the other hand, the words ‘for the life of him’ are chosen carefully. You could argue that because of the word ‘life’, The Boss is left with a newly intimate, though subconscious, knowledge of his own mortality.

Once again, Old Woodifield has been set up as his foil. For Old Woodifield we decode the text as indicative of dementia, but for The Boss, forgetting is an act of will.

RELATED

- “The Fly” is offered as an example of a ‘lyrical’ short story.

- I’m not entirely sure Mansfield did a great job of depicting old age. She never made it to old age herself (and I’m not there yet, either). Time will tell, and I may shift my position. But have a read of Kevin Barry’s award winning short story “Beer Trip To Llandudno”, which explores the middle-aged version of Heidegger’s Being-toward-death. That is a story about middle aged men, written by a middle aged man. As a middle aged person myself, these men’s attitude towards death rings true. The self-realisations about death in “The Fly” feel like middle-aged realisations rather than old-age revelations. Or perhaps Mansfield’s position on death is different yet again, for precisely the reason that Mansfield never made it, even to middle age, and knew full well she would not.

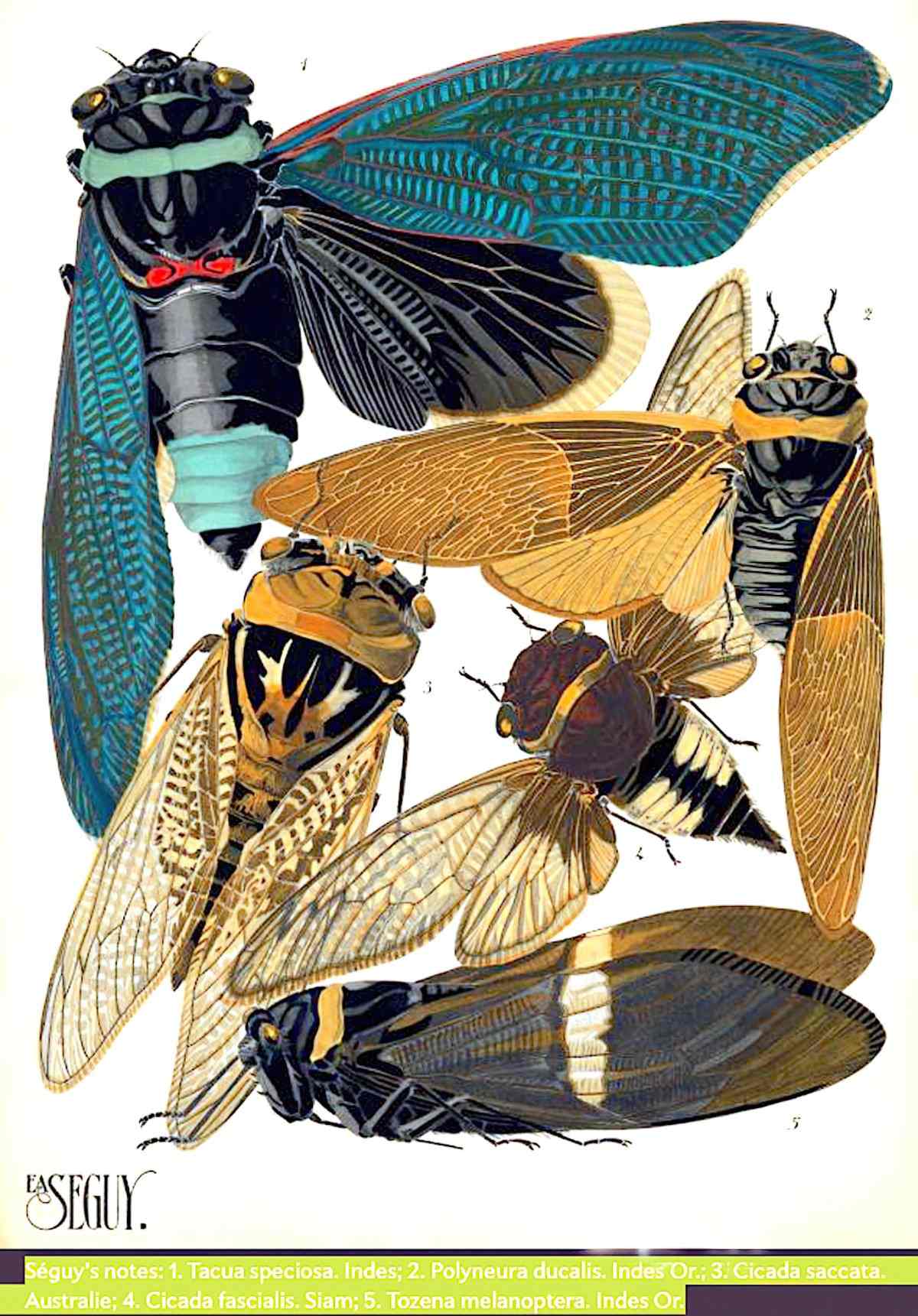

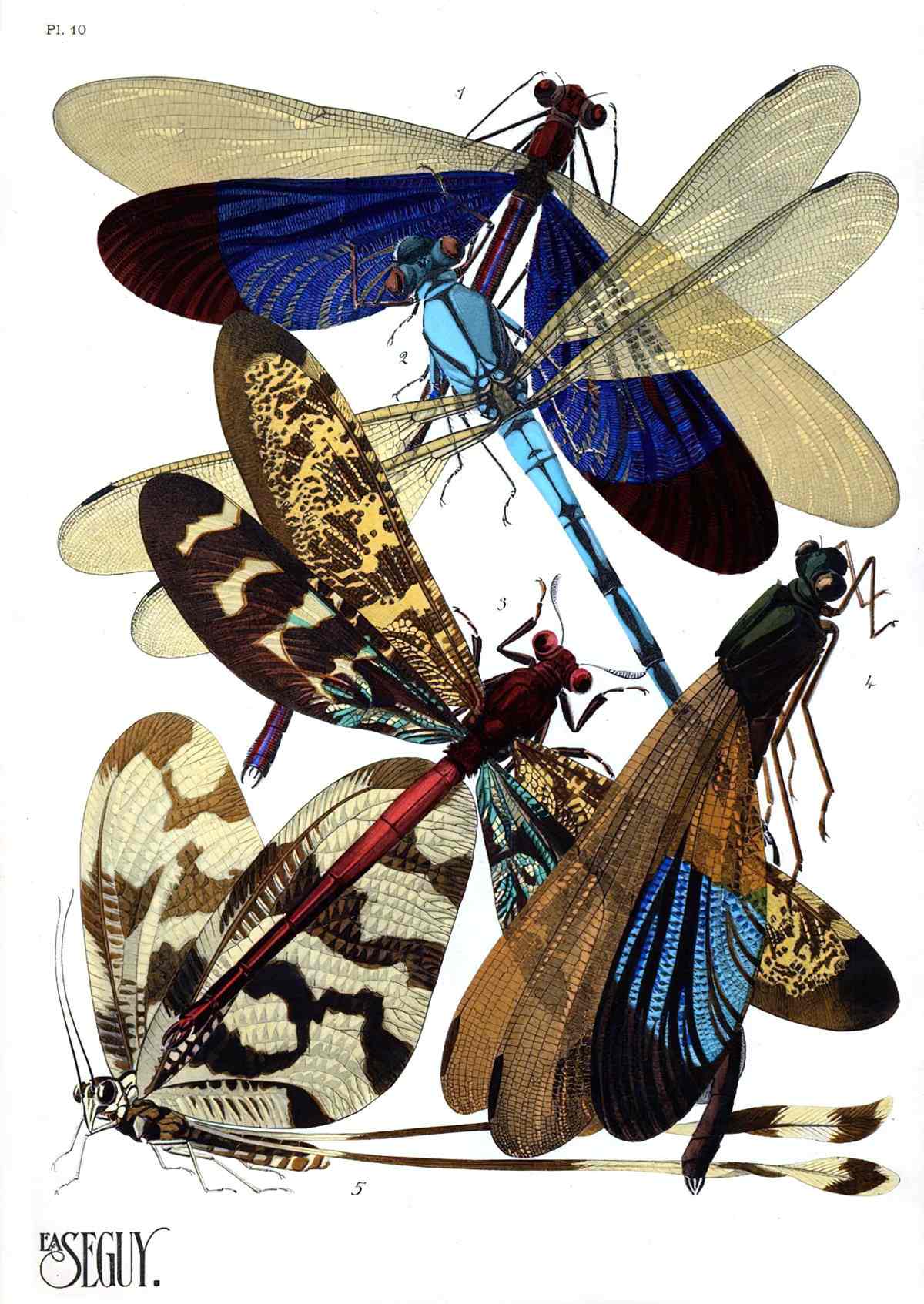

BONUS FLIES FOR YOU

Header painting: Frank Watson Wood – The Cronies ca. 1900