When it comes to modern storytelling in Hollywood animated films for children, Pixar is at the top of the field. In fact, The Good Dinosaur, released late 2015, might have been their very first lemon, depending on what you’re looking for in a film for children.

What happened there? Interestingly, Christopher Orr of The Atlantic felt that perhaps The Good Dinosaur hasn’t been well received by adults because it is Pixar’s first film to explicitly target children (rather than doing the usual ‘dual audience’ thing), which leads me to my main point, as encapsulated by Roberta Trites (Illinois State University) in her book Literary Conceptualizations of Growth:

Disney has a long tradition of appealing to a dual audience. In Disney’s major releases, the story frequently includes adults who need to grow as much as adolescents do in a clear bid to pull parents into theatres along with their children.

This has lead to another shared feature of almost all of the Pixar films, unintended or otherwise: what Trites calls The Pixar Maturity Formula. It goes like this:

A mature female, who is coded as an adult, accepts responsibility for herself and for others. Even in the beginning of the movie, she can intuit how other people will react by anticipating their feelings and the relationship between cause and effect and […] she has a higher cognitive facility than the male characters around her do because she can accept death and control her sexuality.

Trites explains that Pixar characters can be easily divided into two distinct categories:

- Immature, insensitive, conflict-ridden, funny (and therefore very likeable)

- Mature characters (like parents/teachers — and therefore distanced from child)

Note that even though some Pixar protagonists are coded to look like adults, they don’t act like adults. So you can’t judge which are the ‘mature’ characters based on their onscreen age.

As you’ve probably worked out by now, characters from group 2 are pretty much always female, whereas characters from group 1 are pretty much always male.

THE EXAMPLE OF TOY STORY

- Immature characters: Woody, Buzz Lightyear, Hamm the Pig, Mr Potato Head, Rex the Dinosaur, Slinky Dog

- Mature character: Bo-Peep

(In Toy Story, other female characters exist but either never have their faces shown — e.g. mother — or only exist in their relationship to Andy — e.g. baby sister. These female characters can’t be classified at all.)

Toy Story is just one example of Pixar’s Maturity Formula.

The protagonists of The Incredibles, Monsters Inc. and Up are actually adult men. […] The Pixar maturity formula is a script that appears in most of [Pixar’s] films.

Is Gendering Maturity Actually A Problem?

This formula doesn’t just describe stories for children. It explains stories in general.

But depending on the commentator, the female maturity formula can be interpreted as either a positive or as a negative for girls. Below, a Tumblr user interprets the female maturity formula in Star Wars as a sign of general female strength.

friendly reminder that leia has lost her adoptive parents, entire planet, father, husband, son and been abandoned by her brother and yet has never been tempted by the dark side even once

take notes skywalker boys ya’ll weak as shit

acronymed

Some argue that when boys are consistently shown as inept, or when men in commercials are shown as bumbling, that’s actually evidence of sexism against boys and men.

The truth is, this gendered maturity formula in storytelling is terrible for girls and women. Despite many who conflate ‘girl power’ with equality, gender equality in fiction will only happen when we see just as many flawed and weak female characters as there are flawed and weak male characters. The reason it’s safe to depict male characters as bumbling is because we get to see a good number of boys and men in charge of their own destinies — making plans, existing in their own right, growing (or diminishing, in tragedies) as people.

Equal numbers of female characters must go through their very own character arcs before we can say gender equality has achieved. That is the measure. Not ‘kickass’ but flat girls. Not sassy girls standing up for themselves when boys go about their journeys. Not the girl who turns up to do the off-the-page, boring research. Equality is not girls stepping up to the plate to teach boys a lesson when boy main characters are in trouble, in a form of ‘deus ex little mother’.

In order for main characters to undergo full character arcs, they need to be the stars of the story. However. In order to grow, you must start out as bumbling or naive or lacking in some way. There needs to be a scope of change. Female characters need their very own Character Arcs. This character arc, this movement from not knowing to knowing, is the main necessary requirement for ‘hero’. Otherwise you’re just a supporting character.

If we’re to take the good parts of gender stereotyping (girls are awesome because they are so mature!), we’re obliged to accept its damaging flip side. As summarised by Trites:

This cultural narrative ties into at least three conceptualisations that are salient to a cognitive study of growth in adolescent literature. First, the cultural narrative that women are more mature than men is predicated on the false assumption that women [are] already mature as a result of their ostensibly maternal nature. That is, since girls will presumably become mothers and care-givers, they are supposed to somehow automatically — almost magically — mature in order to nurture others.

Second, if nurturance provides girls with an automatic route to their maturation, this cultural narrative falsely implies that females really have only one path to maturity: the predetermined path to parenthood.

Third, this cultural narrative insinuates that male growth is more varied and interesting and thus deserves more attention and praise than female growth.

Carolyn Daniel in her book Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature notices the same thing I’m talking about here. Daniel puts it as follows, though she’s writing specifically about gross-out books aimed at boys:

It is my belief that the reading pleasures of girls and boys are often polarized along the axes of plaisir and jouissance respectively, just as…adult and child pleasures differ. The girl reader …takes up an ostensibly “adult” and accommodating stance in relation to the social order, while the boy is positioned as the “real” child.

(Plaisir is French for ‘pleasure’; jouissance means ‘enjoyment.)

Daniel

Girls don’t mature faster than boys, they’re just groomed earlier for sexual consumption and physical/emotional labour”.

@hunterroseeee

how about we stop saying “boys will be boys” and “women mature faster” and start expecting men to be better

@SketchesbyBoze, 1:19 PM, Feb 24, 2021

The idea that women are the morally superior sex can be seen throughout history in the West, from this angle it seems most obvious in America during Prohibition. Susan Faludi sums up 2017 by looking back on recent history:

American women started the “social purity” movement against prostitution and “white slavery” of girls. The most popular women’s mobilization of the 19th century wasn’t for suffrage — it was for Prohibition, a moral crusade against demon men drinking demon rum, blowing their paychecks at the saloon and coming home to beat and rape their wives. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union quickly became the nation’s largest women’s organisation.

Did that war against men behaving badly feed into the larger big struggle for women’s equality? In many ways, yes: Susan B. Anthony herself began as a temperance organizer. But a good number of women who railed against alcohol’s evils shrank from women’s suffrage. Fighting against male drunkenness fell within the time-honored female purview of defending the family and the body; extending women’s rights into a new political realm felt more radical and less immediate. Frances Willard, the temperance union’s formidable second president, eventually brought the organisation around to supporting the female franchise by redefining the women’s vote as a “home protection” issue: “citizen mothers,” as the morally superior sex, would purge social degeneracy from the domestic and public circle.

The New York Times, The Patriarchs Are Falling. The Patriarchs Are Stronger Than Ever.

That was America’s history, but similar stories played out in countries such as Britain, Australia and New Zealand around the time women were fighting for the vote. “We deserve the vote because look, we’re morally upright people.”

The Female Maturity Formula Is Everywhere

The female maturity formula can be seen all over the place, not just in Pixar films. Here are just a few case studies of standout examples.

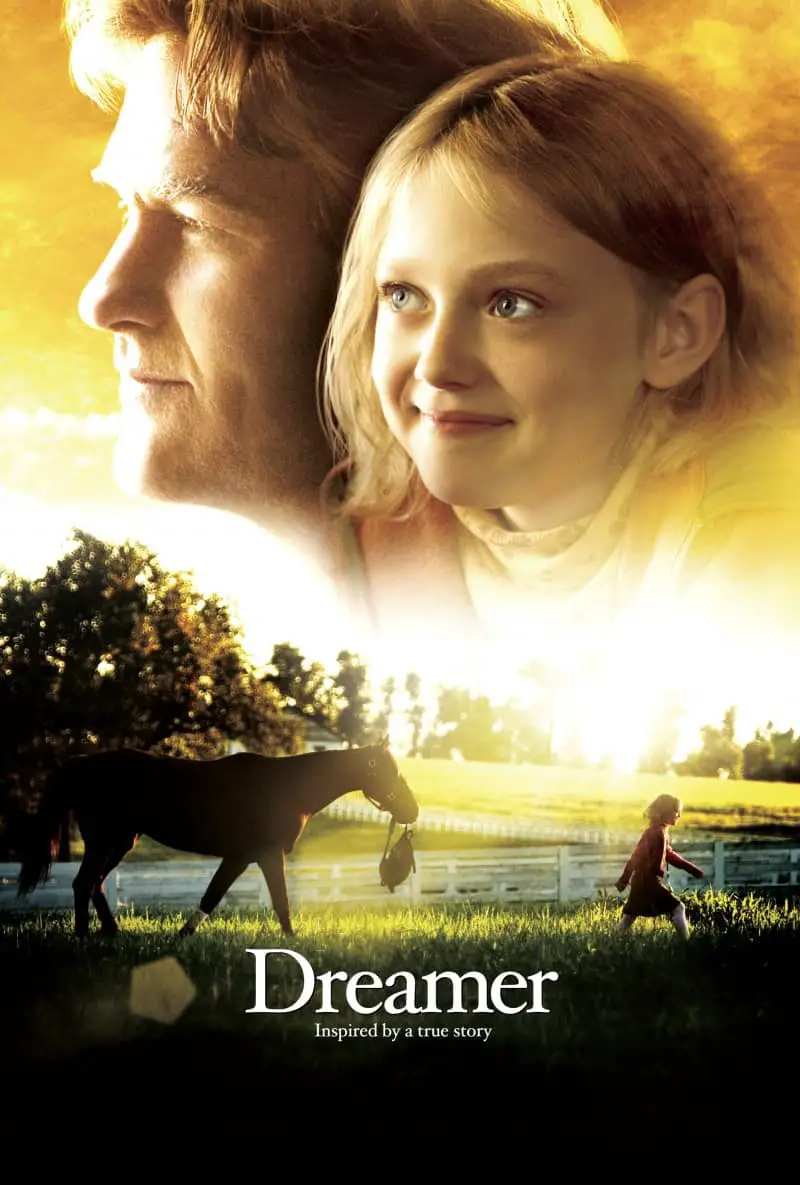

Dreamer

The worst example I’ve seen in a film ostensibly for children is a Dreamworks production starring Dakota Fanning. As a child actor, Fanning often got these ‘old soul in a young body’ type roles. This time we see her in Dreamer (2005), which is about the emotional arc of the father, despite being marketed and ostensibly made for adolescent girls. Go to the IMDb entry and you’ll be recommended the Flicka franchise and Black Beauty as view-alikes. Make no mistake, this film ends up being about the father. As mentioned in the logline, the girl (Cale) ‘catalyses’ the father into action, and into his own emotional arc.

Cale Crane catalyzes the rescue and rehabilitation of Sonador, a race horse with a broken leg.

To save you watching it yourself, The Roger Ebert website offers further details of how, exactly, Cale inspires her father:

Ben later admits, “If Cale hadn’t been with me that night, I’d have left that horse on the track.” But Cale is there, and looking at her big sad eyes, her father has the leg splinted and wrapped, and brings the horse back to the stable. This inspires an argument with Palmer, who is forced to regard the results of his own bad judgment. Ben resigns, taking a pay-out — and the horse.

I can’t think of an inverse example of film-making and marketing, in which adolescent boys are expected to sit through a movie length story about how a boy inspires the emotional arc of his mother, in which most of the talking is done by the women, between women.

The Man In The Moon

A film with a similar vibe to Dreamer was Reese Witherspoon’s debut as a young actress in a 1991 coming-of-age film called The Man In The Moon. 14-year-old Dani Trant is the youngest character in years but repeatedly demonstrates better communication skills than the men in her life (namely her father and the attractive young man next door), probably due to evenings talking with her kind older sister, who functions as a mentor. Dani tells the boy next door she loves him and he literally turns away.

There is another massive problem with this film, but it is inextricably linked to the Female Maturity Formula. Since Dani arrives as a fully-formed individual on this Earth, she (and the audience) is unlikely to have any kind of awakening when her own father gives her a hiding with a belt for sneaking out one stormy night. Later, it’s little girl Dani who tells her physically abusive father that she understands why he did it — he didn’t mean to thrash her — he was just scared. The father literally gets out of the car and walks away, without acknowledging the fact (to woke 2017 eyes) that he is grooming his daughter to be abused by men who love her. For girls, even in a coming-of-age story, the girl is all-too-often emotionally articulate and self-aware from the get-go. ‘Coming-of-age’ in this sort of story simply means ‘falling in love for the first time’ (which is why some people profess to hate the ‘coming-of-age story’ even though there are plenty of great ones).

Stephen King’s IT

Guess which of the child characters below takes the maternal lead at the point where decisions must be made, bravery must be mustered?

What do you suppose goes through the minds of people creating these stories? If anything?

We might have a bit of a gender diversity problem here fellas, given how it’s, you know, 2017 and certain reviewers are harping on about wanting more ‘strong female characters’ and all that. Yeah but no, there’s no gender problem in this particular film. It’s still totally relevant and totally needs another remake. I mean, step away from the metrics and look at what the girl does. She’s the most sensible and brave of them all! If anything, the boys are misrepresented!

A Brief History Of The Female Maturity Formula

The Female Maturity Formula of storytelling all started long long ago, with The Odyssey, and the loyal sidekick-wife of Odysseus, Penelope.

In Homer’s The Odyssey … Odysseus’ son Telemachus tells his mother, Penelope, to “Go back up into your quarters. Speech will be the business of men.”

Men Have Been Telling Women to Shut Up for at Least 3,000 Years

We’re now so used to this trope it’s hardly noticeable anymore. It’s especially prevalent in comedies, probably because male comics need a straight-‘man’, (which really should be renamed ‘straight woman’) and most of the Pixar films are a mixture of ‘adventure + COMEDY’, after all.

Beware The Story With Two Or More Boys And One Girl

Okay, let’s step away from Pixar for a minute. Take Sony Pictures’ Monster House (2006). If you’re familiar with children’s stories you already know this from the promotional image: The boy in the middle is The Every Boy (he’s white and average BMI); his chubby best friend is the comical character who is, developmentally, slightly behind the main character. He wants to go trick-o-treating, for instance — our main boy thinks he’s too old. These two have a problem to solve, but they don’t have any clues how to solve it until the devious, whip-smart, no-nonsense girl comes along to drive their action forward. (Jenny also serves as the love interest.)

The two-boy, one girl trio is very popular across middle grade stories, but take a close look at who gets to crack the jokes. Who is likeable? Whose eyes do we view the story through? Most importantly in this discussion: Who gets the chance to develop as a person?

The Female Maturity Formula is closely related to The Minority Feisty trope which itself came from The Smurfette Principle. We see it also in ParaNorman, a horribly sexist film produced by Laika. In fact, writers seem afraid to step away from this formula. It has proved a hit with largely uncritical audiences.

Children’s writers learned from comedy for adults, of course.

The Female Maturity Formula In Comedy Series

The main characters of Black Books are Bernard, Manny and Fran. Each of these characters has major flaws — Fran is an alcohol-addicted, self-absorbed shopkeeper who ‘sells a lot of wank’ and is probably on the sociopathic spectrum. But when the boys need to learn a lesson, it’s Fran who sorts them out. Here the three of them stand, just after Bernard has fired Manny on his first day working at Black Books. Fran comes in to give Bernard a dressing down for being mean. The source of the comedy in this scene comes from Bernard’s behaving like a little boy and from Fran behaving like his mother. While Fran is an equally flawed human being, the writers will happily use her if they need a mother figure, and audiences don’t question it.

Throughout The IT Crowd it is Jen who plays the motherly role to Moss and Roy. Like Fran in Black Books, Jen has her own significant moral and psychological shortcomings, but she too comes in handy as the mother figure when the male characters need to work something out. This is the overriding humorous dynamic that runs throughout the entirety of the series. Because there is such a strong history of the Female Maturity Formula in 3000 years of storytelling, writers assume it wouldn’t work if the genders were swapped. And yet…The IT Crowd often switches gender stereotypes around for laughs (as they do in this very scene, in fact, with Roy calling Moss his wife). The problem is, comedy needs the audience to have a shared understanding of gender roles in order for the comedy to work.

It is therefore very difficult for comedy writers to lead the charge when it comes to forging ahead with brand new tropes.

The tentpole example of the Female Maturity Formula in terrible sit-coms would have to be the wife from Everybody Loves Raymond, whose long-suffering, eye-rolling wife plays the straight-man to Raymond’s antics.

This gender dynamic in American sit-coms is so common that comedian Louis C.K. satirised it in the first scene of season 2, episode 7 of Louie: Oh Louie!/Tickets. (It’s such a shame Louie C.K. is such a predatory asshole in real life, showing that an understanding of a sexist culture doesn’t necessarily help one to rise above it. Ditto for Jay Asher.)

FUTURAMA

In Futurama we have Turanga Leela:

[Leela] is one of the few characters in the cast to routinely display competence and the ability to command, and routinely saves the rest of the cast from disaster, but suffers extreme self-doubt because she has only one eye and grew up as a bullied orphan.

Wikipedia

By the time Futurama came along, its audience was used to this dynamic in The Simpsons, with Marge and Lisa being the sensible characters of the show.

All this comes to a natural head with the belief that women just aren’t funny.

The “why women aren’t funny” statement Hitchens made years ago is coming into focus that it isn’t that we aren’t funny–it’s that men lack an ability to see life through our experience, and lack the empathy to want to try. In other words, they don’t get the joke and never wanted to.

Jen Kirkman on Twitter, 3:15pm, 21 Nov 17

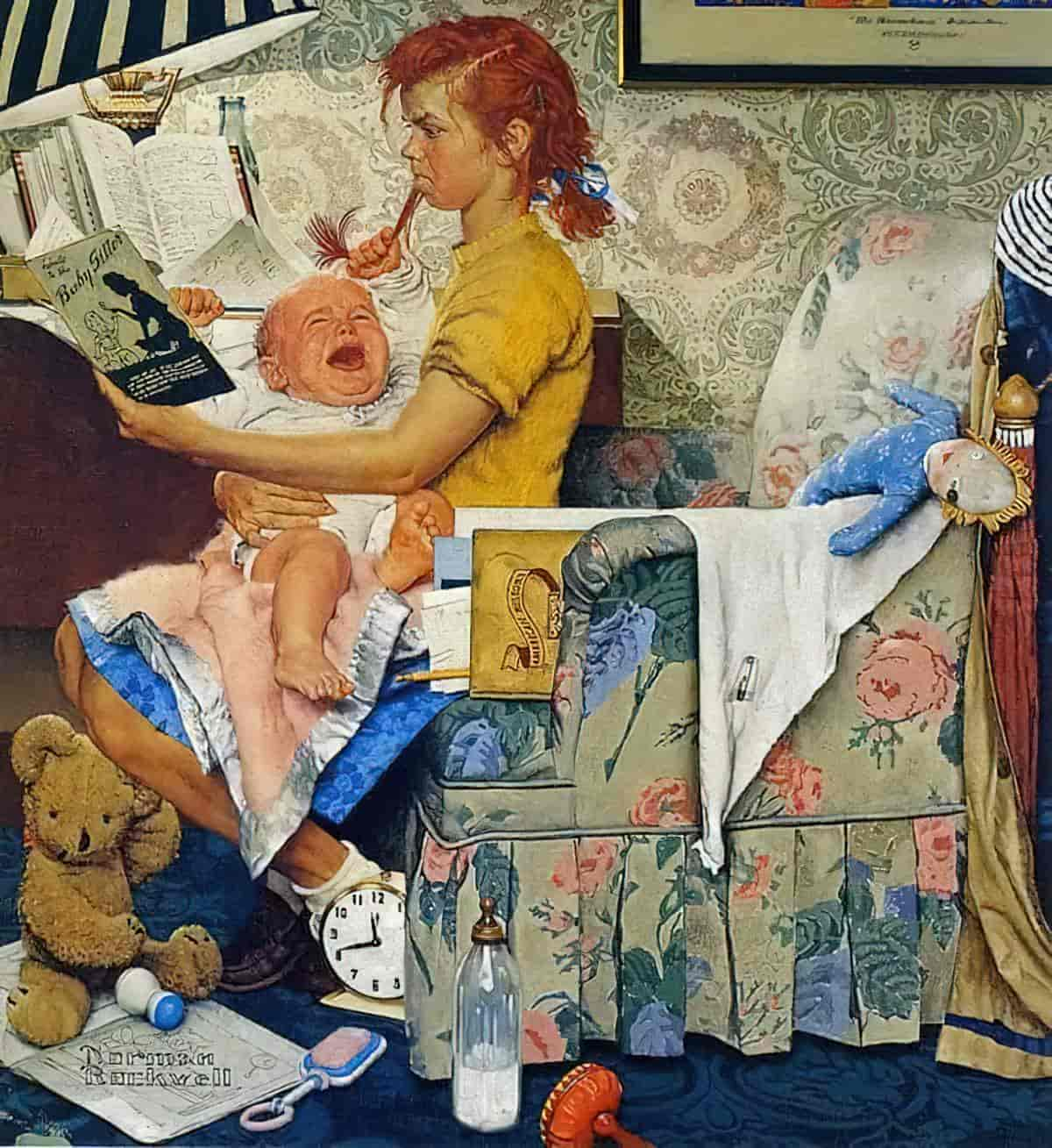

The Female Maturity Formula In Picture Books

Old Tom

Books for the youngest readers are not exempt. This is cultural conditioning that happens from birth. Sadly, sexism sells. Stories which conform best to long-held storytelling rules are those most likely to be made into children’s television shows.

Old Tom is not the most congenial or mannerly cat, but his owner Angela Throgmorton loves him dearly. Even she will admit, however, that he’s been a bit of a pill lately. When she wins a vacation for one, Angela is pleased to inform Tom that he must stay home. She suggests he clean his room.

from the Kirkus review

The Girl Swot As Variation On The Formula

There is so much to say on this particular topic that it deserves its own post.

But it doesn’t have to be like this. In Seinfeld we saw equal opportunity Assholery with Elaine Benes. We need that in children’s stories, too.

The Era Of The Girl Boss

Since Roberta Seelinger Trites first named the Pixar Maturity Formula, something happened in our culture in the name of feminism: The rise of the Girl Boss.

Gabrielle Moss writes about this over at Medium: The Girlboss Era is Over. Welcome to the Age of the Girlloser. The article is somehow both angry and funny. (Another rule for femme people: If you want to show anger, at least make it funny.)

When she reached the age of 28, Moss started to be asked when she was about to have children. People asking her this should’ve known her better than to ask. She came to a solemn realisation: The idea of the slacker woman doesn’t exist. Despite professing to have no interest in babies, people told her time and again, “You’ll get the hang of it once you have a baby.” Yet the same-aged men in her life and in pop culture weren’t getting the same message.

Moss points out that the Girl Boss empowerment movement of the 2010s benefited capitalism without benefiting women. In this movement, women are not full humans. Women sometimes also want to be slackers, with space in their lives for imagination and messing up.

To borrow Gabrielle Moss’s terminology, we need more girl-losers in children’s stories. Girls can’t be what they can’t see!

FURTHER READING

Junot Diaz and the Problem of the Male Self-Pardon from Slate is inextricably linked to everything above.

I mention Penelope above as the O.G. Mature Female in storytelling. Margaret Atwood’s 2005 novel The Penelopiad parodies the foundation myth by giving Penelope a voice. This is radical because Penelope remains mostly silent in the other versions of The Odyssey.

Zog by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler makes for another interesting case study.

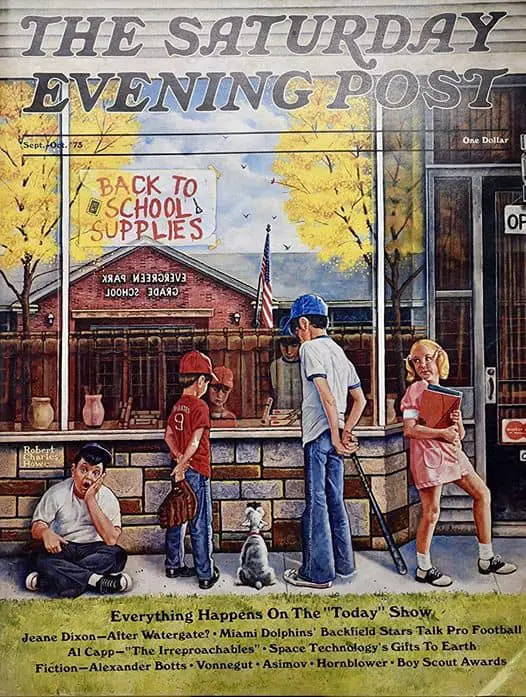

Header illustration: Cover by Robert C. Howe, 1973. The girl seems to exist to show the viewer how full of life and adventure the boys are. The girl clutches a school item to her chest and stands with her back turned to them, suggesting she is not part of their boisterous fun. Or, if she is, she knows she’s supposed to act differently.