It’s almost impossible to read Katherine Mansfield’s “The Escape” (1920) without linking back to the author’s own biography. But perhaps we shouldn’t look to Mansfield’s relationship with a man in order to understand where this story might have come from. Biographer Claire Tomalin has said this about Mansfield:

[Mansfield] was a liar all her life — … and her lies went quite beyond conventional social lying. Whereas Murry “forgot” things or distorted subtly, she was a bold and elaborate inventor of false versions. A charitable view of the origin of this habit could be that it was a bid for attention, a response to feeling obscured and overlooked in a large family with an inattentive mother; this may then have developed into a pleasure in dramatising for its own sake, making herself into the heroine of the story. If the truth was dull, it could be artistically embroidered; and if she was the heroine of her own life story, lies became not lies but fiction, a perfectly respectable thing.

A Secret Life

I don’t necessarily believe we need to go into a person’s childhood to understand why they do the things they do. The Internet phenomenon of catfishing has taught us that sometimes drawing others into our fantasies makes our fantasies even more fun. Couldn’t it simply be that?

Whatever her reasons for invention, Mansfield had first hand insight into fantasists. “The Escape” is the ultimate fantasist story, evident from the title.

There’s more to this story than ‘insight into a fantasist’, however. That alone would be quite boring — like hearing all about someone’s dream.

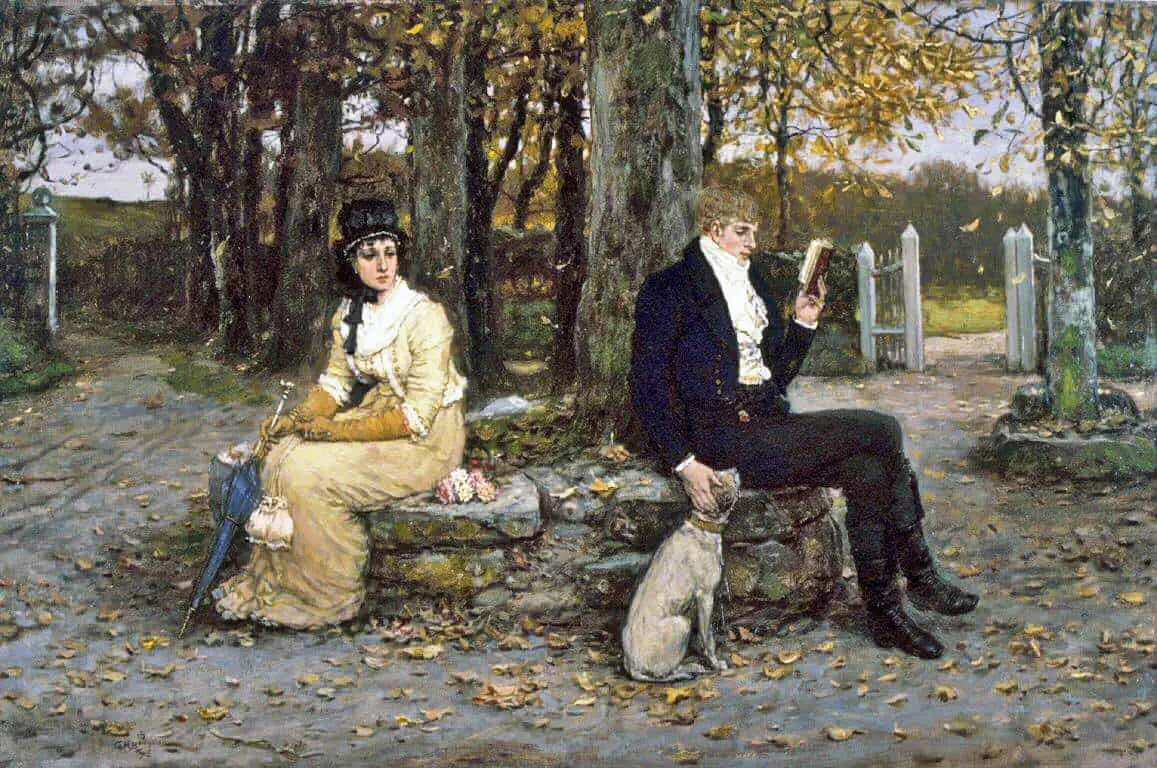

Mansfield seems to be conducting an experiment: What if an author gave silence to a man and speech to a woman?

“THE ESCAPE” AS ‘PLOT-LESS’ SHORT STORY

Much has already been said on Mansfield’s life and her intimate relationships, so I’d like to focus on the story structure of “The Escape”, which is a classic example of a story in which ‘nothing happens’. It’s often said that Mansfield didn’t write plots.

Of course, that’s rarely true of any enduring tale, and it’s not true here, either. “The Escape” conforms — with subtlety — to standard story structure.

‘The plots of my stories leave me perfectly cold.’ They tend to begin at the heart of a situation, without preamble (although flashbacks and reflection feature), and frequently they end abruptly. Primarily, Mansfield is concerned with the psychology of her characters, many of whom are isolated, frustrated and disillusioned. She moves between them, using focalisation and free indirect speech to communicate their thoughts. Often they feel that they have ‘two selves’ and, repeatedly, there is a sense of wasted potential and a yearning for escape.

An Introduction to Katherine Mansfield

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE ESCAPE”

Characters remain unnamed in “The Escape”, which keeps the reader at a distance and also tells a story of ‘people’ rather than of ‘individuals’. Writers sometimes avoid naming characters in an attempt to say something universal about humanity.

SHORTCOMING

As far as moral shortcomings go, this woman is full of them. She’s not sympathetic at all. Whatever’s going on with her, you can bet your bottom dollar it runs deeper than ‘missing the train’. But Mansfield doesn’t let us in on any of her history. There are no flashbacks to earlier that week, when her husband really did do something to make them miss a train, which meant they missed their connecting train… we get no solid clue that the man is the problem. This is interesting, because another writing choice would have been to include that. Mansfield was not especially concerned with making her characters ‘likeable‘, not even her female characters, for whom the likability bar is set higher.

The woman is also shown to be melodramatic — the unseen narrator is in on her melodrama, sensing it along with us, the reader.

The husband, even at this point in the story, imagines his wife as dead, as if a Queen in Egypt.

Whenever there’s focus on a woman’s handbag in fiction, there inevitably comes some judgement with that: We are told about her make up and other female fripperies.

What is this detail designed to do? Are we meant to judge her as insubstantial because these things are ultimately superfluous? There is a long history of judging women based on female accoutrements. For more on that particular type of misogyny, see the work of Julia Serano, because it really comes to the fore in discussions of transmisogyny.

But it’s equally possible to read that detail as the husband emphasising the importance of her handbag contents:

[I]t could be that he is emphasizing the importance of the trivial objects in her bag, since they are presented as equivalent to the treasures which Egyptians were buried with. Thus,Mansfield’s symbolism presents the husband as viewing his wife, and her handbag’scontents, in a way which is potentially both elevated and trivial, in one short sentence.

However, there is a scene later where she complains about his smoking, so it is very possible that the broken cigarette in her bag is not hers. Maybe it is a cigarette which she took from him and broke in a fit of anger. If this was so, she could have thrown it away immediately, but instead she keeps it. This suggests that she does not intend (or even want) to separate from him, and that maybe she will be with him to the grave like the treasure of the Egyptians, although she is constantly irritated by his overly relaxed attitude and actions.

Masami Sato

DESIRE

On the surface, the woman wants to be in time for her train. She’s perseverating on this, and no one around her is moving fast enough. Her inner turmoil is at odds with the holiday feeling around her.

Underlying her wish for others to hurry, I sense an imperative personality, who needs to control others around her as a proxy to controlling her own inner turmoil, whatever that is. This is an another story of repression, probably. I see her irritation directed at the driver as misplaced irritation she feels in regard to her husband. But because she’s married to her husband, she can’t direct her frustration directly at him.

Anyone who has worked in the service industry knows this dynamic well: The quietly simmering couple, one of whom will find something terribly wrong with your service, for some strange reason…

The ‘escape’ of the title, to me, is about this woman’s wish to escape the difficulties of her own marriage.

OPPONENT

The real opponent is the husband, but the proxy opponent is the driver, who opposes her only by passive-aggressively refusing to hurry as she requests.

PLAN

The reader doesn’t even know where this couple is going. We deduce they’re on holiday — wealthy enough to spend months at a time doing not much at all except ‘have fun’ in each other’s company. Perhaps they’re even on honeymoon, trying to come to terms with each other’s vastly different travelling styles — his laidback, hers highly structured.

The woman’s subconscious plan is to direct her frustrations away from her husband, but it needs to come out somewhere. It comes out on someone working in the service industry.

Another story in which service workers bear the brunt is John Cheever’s “Reunion”.

BIG STRUGGLE

Insofar as “The Escape” is a road-trip journey, something needs to happen which leads to the woman’s (or the reader’s) revelation. This doesn’t need to be some big big struggle, and Mansfield never wrote your classic, masculine mythic structure anyhow.

But what? What happens in this horse-and-cart seaside journey to change the emotional valence?

The precious parasol falls off the cart. Parasols, I suspect, were important to Mansfield. There’s emphasis on the umbrella in her story “The Voyage”. One’s umbrella/parasol was almost a part of a woman’s self — as integral to her identity as her handbag.

In any case, the woman realises it fell off, then the cart driver reveals he knows it had fallen off but didn’t stop because no one said anything. He was in a bit of a bind really, because he is also expected to hurry. The real problem is that he’s not on his customer’s wavelength at all: He doesn’t understand her wish to hurry; nor does he understand the importance of a parasol.

ANAGNORISIS

At this point, Mansfield’s ‘camera’ stays with the cart and viewpoint switches to the husband who until this point has been absent in his presence.

We learn his way of dealing with his wife is to pretend he’s basically dead. He becomes a fiction.

In fact I wonder if one legitimate reading of this story is that he actually did die in cart, and his wife is so preoccupied with getting from here to there, and on her precious parasol, that she wouldn’t even notice if he were dead.

In that case, the revelation would go something like: If you spend your entire life focused on the small things you miss the really big things, and take people for granted.

But since this is a Mansfield short story, the tree is important. Extreme noticing of a tree is also important in another story, “Bliss” (that masculine pear tree). Here, by Mansfield’s description, it’s probably a beech tree. Unlike in “Bliss”, this tree offers the husband nothing positive. As used here, the usual tree symbolism (as life giving) is wholly inverted: These trees are portrayed as suffocating. In this example of pathetic fallacy, a character feels suffocated (by marriage), so everything he sees around him seems to suffocate him.

NEW SITUATION

After the double line break we have another scene, but the reader doesn’t know what this is:

- Is it a flash forward?

- A flash back to an earlier journey?

- An entirely imagined ‘dream space’, where he goes frequently to escape the reality of his wife?

Mansfield doesn’t let us know. The scene therefore functions in a similar way to her child-elderly character duos in stories such as “The Voyage” and “Sun and Moon” — the reader is encouraged to see time as a series of moments in a life rather than focus on the sequential, linear nature of time. Our experience of life as lived is less linear than it is like that, especially for the imaginatively capable, in which it’s possible to live a number of different lives, including our own, owing to the power of the mind to jump backwards, forwards and sideways.

The man has developed the ability to separate mentally from his wife. This may be the first moment he did this, or it may be his usual mind trick. In an era when divorce was rarely an option, I expect this couple will live out their lives together in body but completely apart in spirit.

The final statement of the story can be read as sardonic: “so great was his heavenly happiness as he stood there he wished he might live for ever”.

In the end, what position does Mansfield take on this fictional fantasist? She seems to be arguing that not all fantasies are acceptable. Fantasies can instruct but also mislead. They can accurately represent alternatives or they can do the opposite. Sometimes, fantasies can simply reconstruct the limits of the status quo. But they are at their most seductive when they seem to promise escape.

(The graphic in the header is a painting by Monet called Road at La Cavée, Pourville, 1882.)

ESCAPE IN FOLK TALE

Index of Escape by Deception from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966.