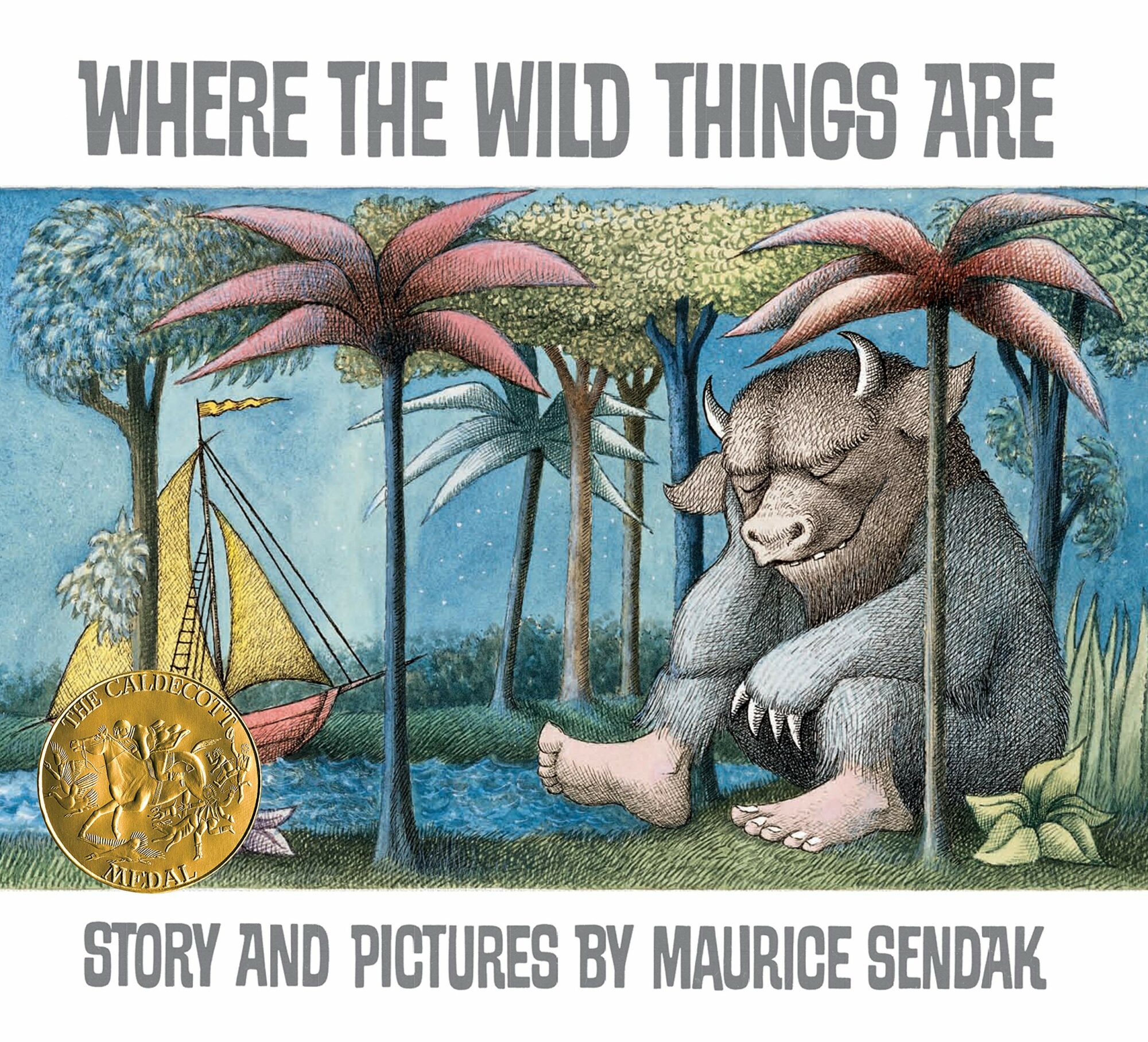

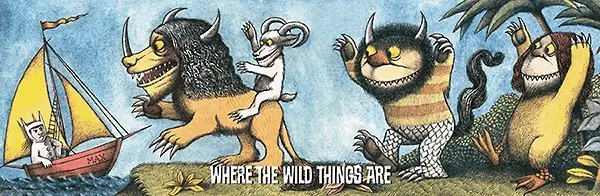

“Where The Wild Things Are” by Maurice Sendak is the picture book that changed picture books forever.

The picture book began to be understood, after Maurice Sendak, as something extraordinary – a fusion of images and limited vocabulary which authors such as Julia Donaldson, Lauren Child, Alan and Janet Ahlberg, Emily Gravett and more have turned into a post-modern art form.

Amanda Craig

When I started reading books about picture books the first thing I noticed was how much the books of Maurice Sendak are referenced as primary sources, especially Where The Wild Things Are. Handy hint: If you’re thinking of reading academic literature in a bid to understand children’s books, have the Sendak oeuvre at your side. (Also Rosie’s Walk, the picturebooks of Anthony Browne and Chris van Allsburg.)

I find it ironic that the Book Depository description of Where The Wild Things Are includes the phrase: ‘Supports the Common Core State Standards’. Sendak famously did not write for children, saying, “I write stories, then someone else decides that they are for children.” I wonder what he would have to say about the heavily pedagogical motivations behind adults encouraging children to read his stories.

Sendak readily acknowledged his inspiration for his stories, and this one was apparently inspired by King Kong.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE”

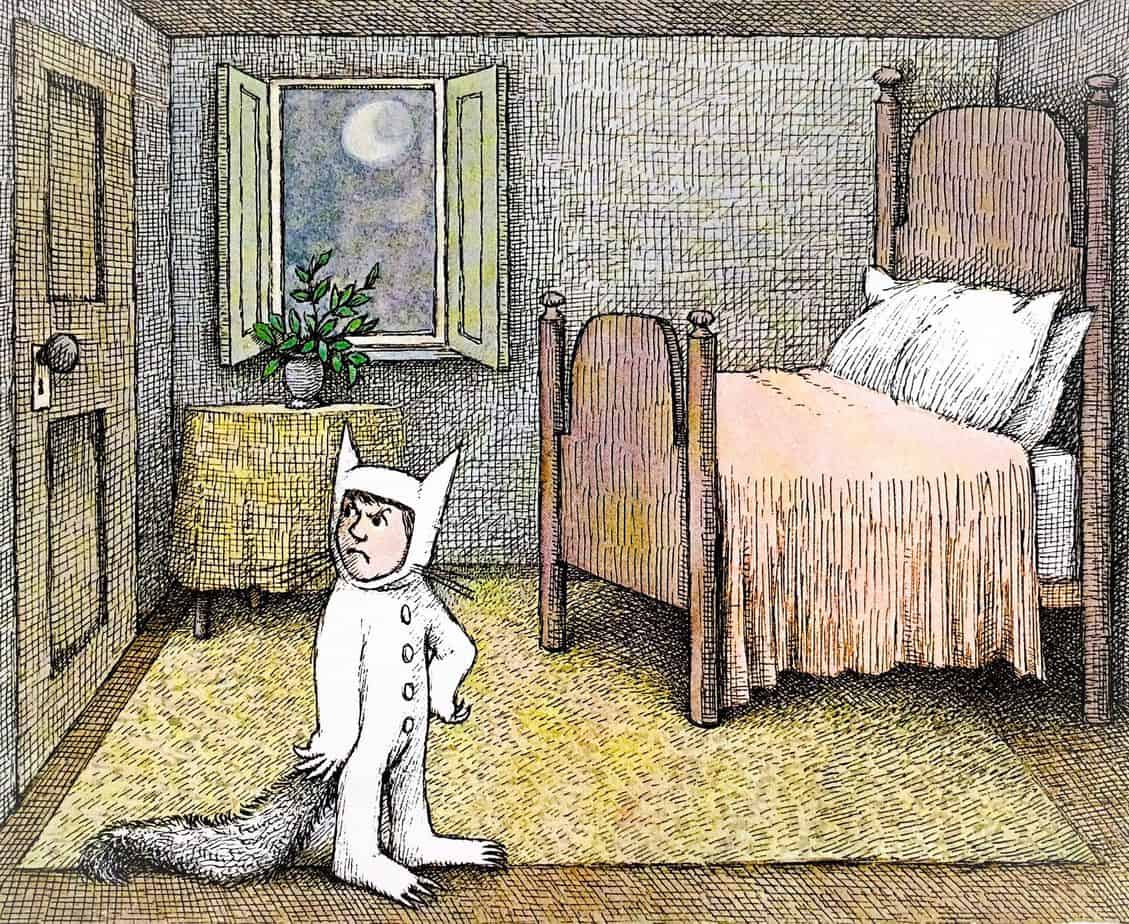

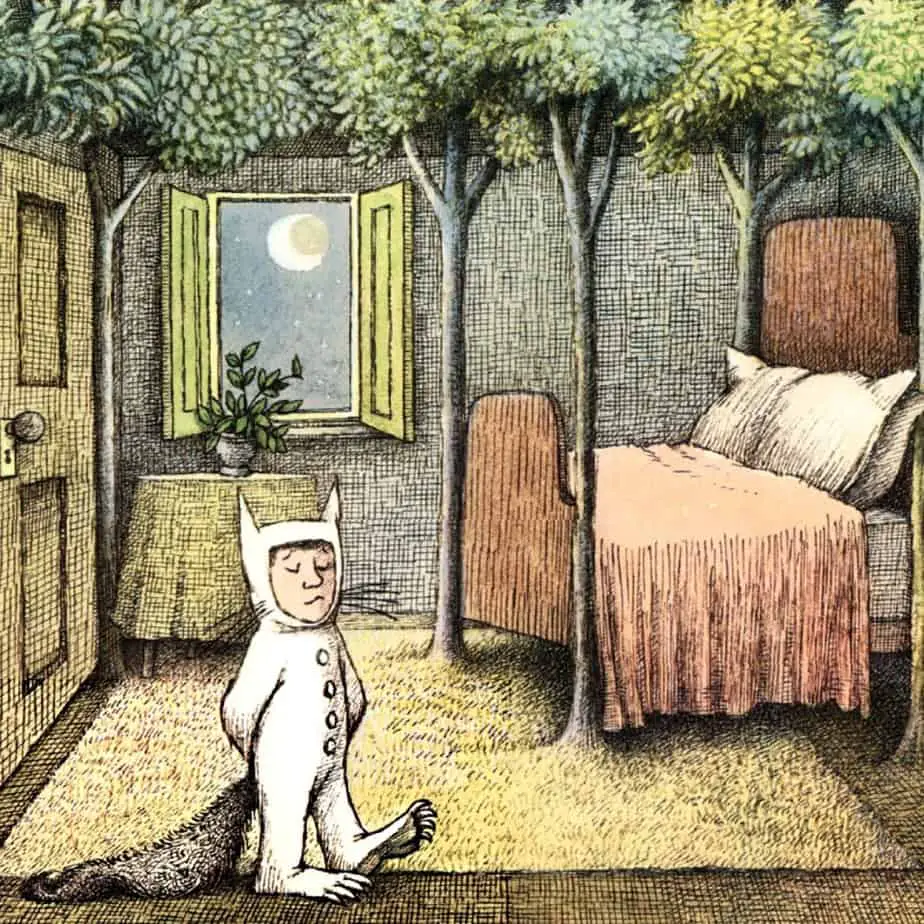

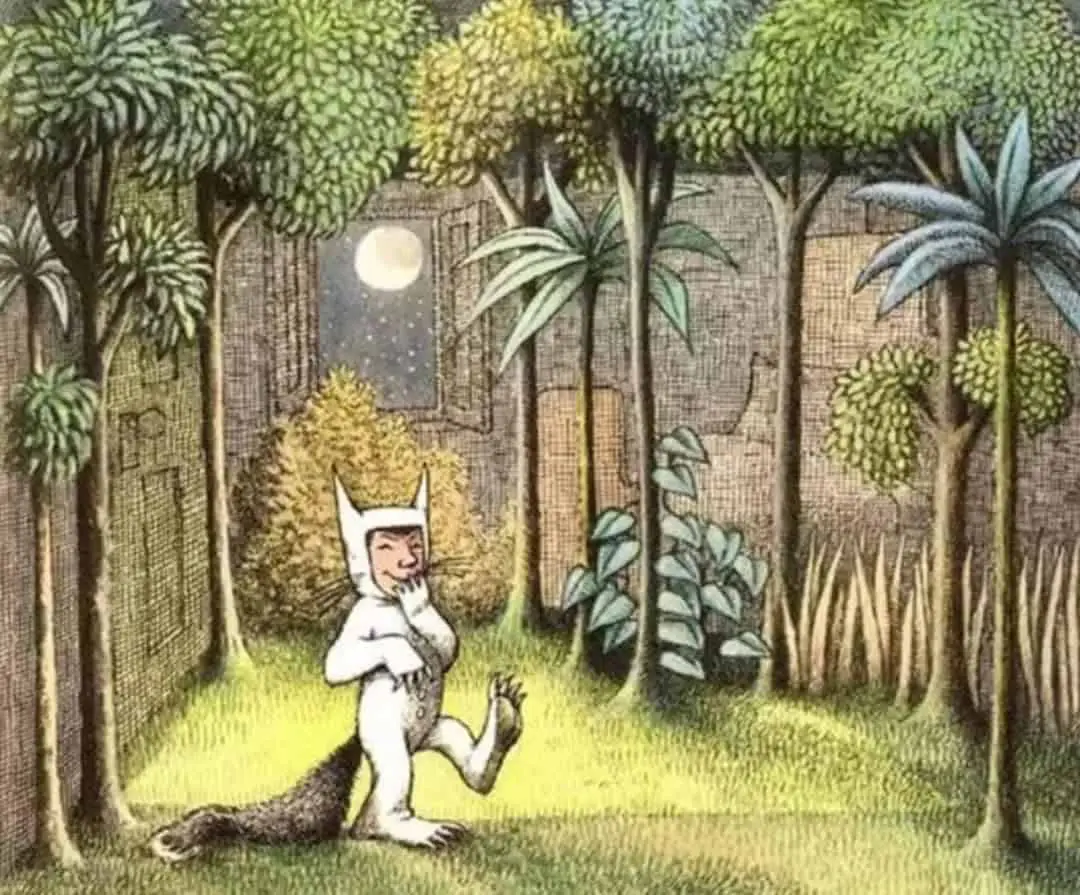

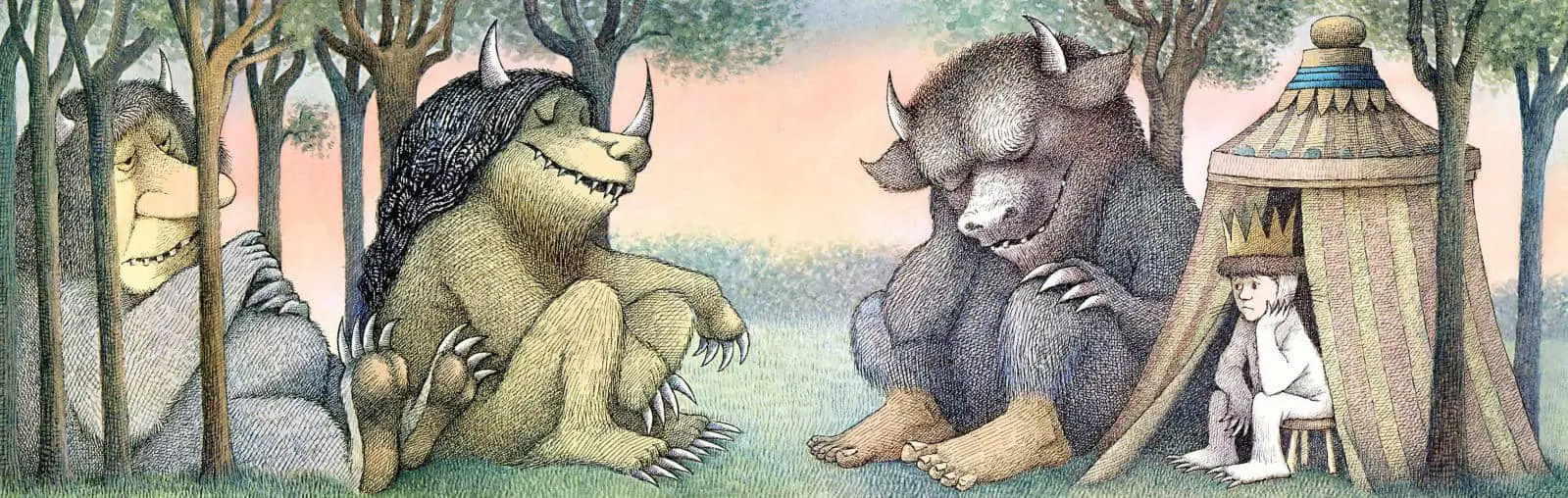

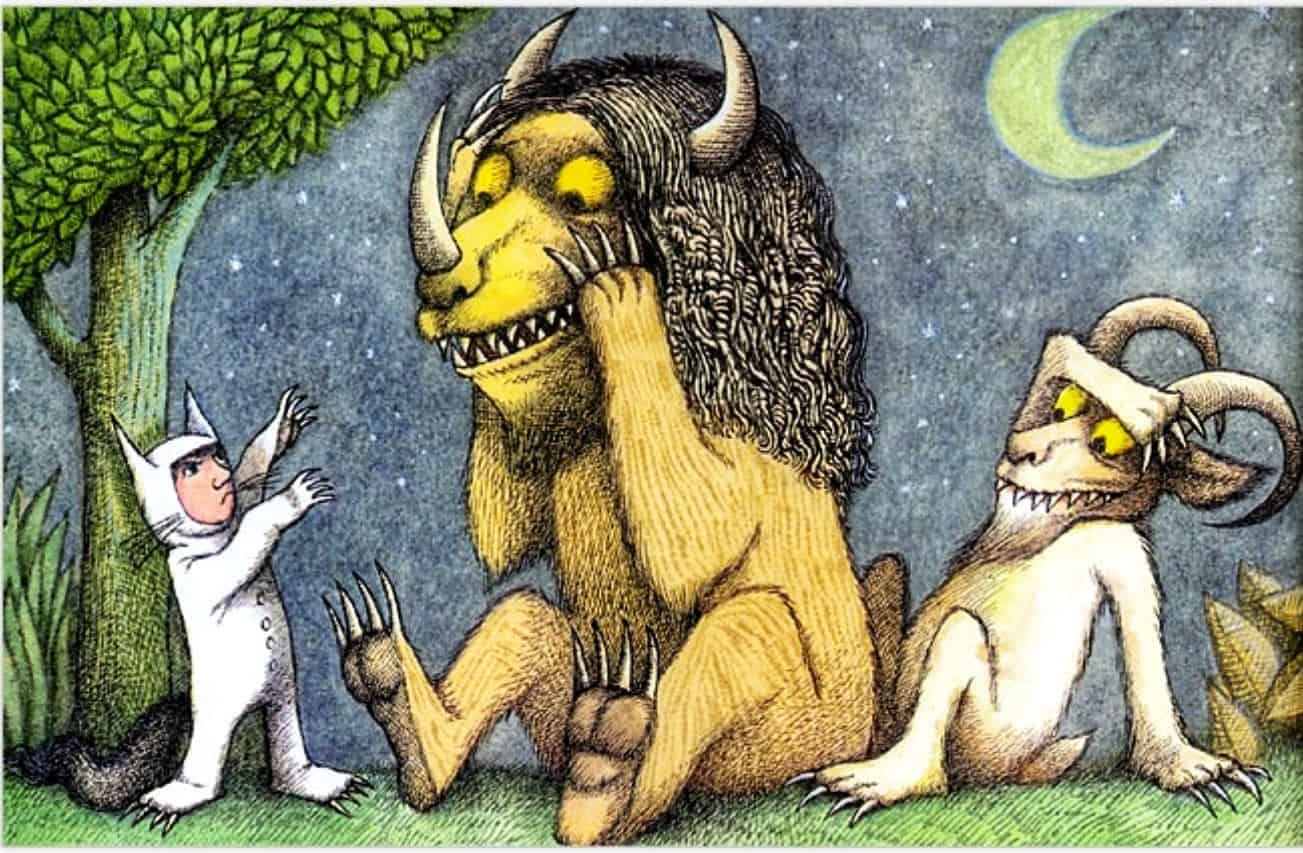

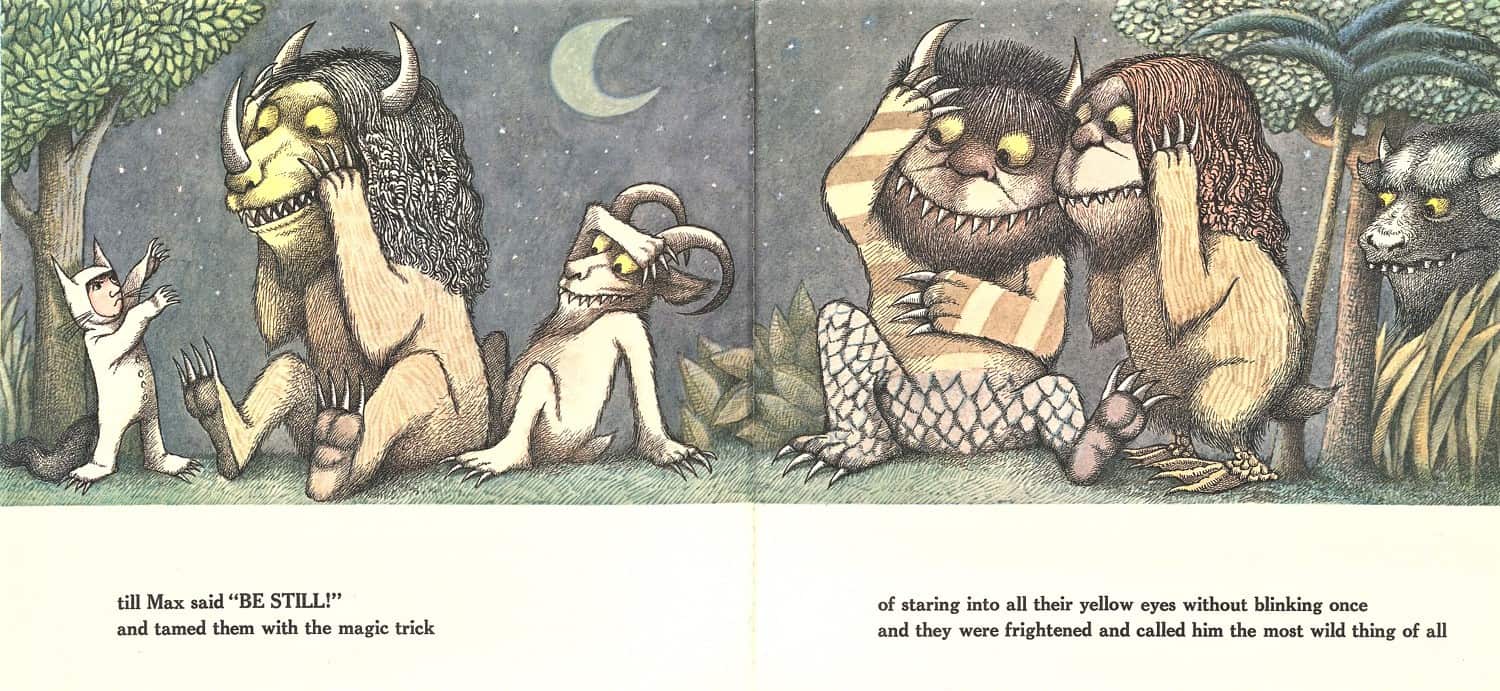

This story is about a boy named Max who, after dressing in his wolf costume, wreaks such havoc through his household that he is sent to bed without his supper. Max’s bedroom undergoes a mysterious transformation into a jungle environment, and he winds up sailing to an island inhabited by malicious beasts known as the “Wild Things.” After successfully intimidating the creatures, Max is hailed as the king of the Wild Things and enjoys a playful romp with his subjects; however, smelling the food that his mother has delivered for him, he decides to return home. The Wild Things are dismayed.

“Pretend” often confuses the adult, but it is the child’s real and serious world, the stage upon which any identity is possible and secret thoughts can be safely revealed.”

Vivian Gussin Paley, The Boy Who Would Be a Helicopter

THE ENDURING APPEAL OF “WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE”

Where The Wild Things Are is an example of a carnivalesque text. This is a form which endures — young and old audiences love to be whisked away on a jaunt of the imagination, back in time for tea, consequence free.

Marjery Hourihan points out other, more irritating, reasons for this book’s enduring appeal in Deconstructing The Hero:

The persistence of this pattern which inscribes the myth of Western patriarchal superiority is apparent when we see that Maurice Sendak’s celebrated children’s picture book, Where The Wild Things Are (1963), tells a story which is in essence exactly the same as the story of Odysseus. A small boy called Max, dressed in his wolf suit, misbehaves and threatens his mother, so he is sent to bed without his supper. Once in his room he embarks on an imaginary journey, through a forest and across an ocean, to the land where the wild things are. Despite their ferocious appearance Max tames them by saying ‘Be still!’ and looking into their eyes without blinking, whereupon they make him their king. He is given a crown and a scepter and they obey him. Max and the wild things indulge in a joyous and anarchic rumpus which stretches across six pages of illustrations, but finally, lonely for love, Max stops the rumpus and departs despite the wild things’ plea: ‘Oh please don’t go — we’ll eat you up — we love you so!’ He sails home, into his own room where he finds that a hot supper is waiting for him.

Like Odysseus and all the other heroes of antiquity, Max is the primary force in his story. His goal, like Odysseus’s, is to regain his kingdom (his position as a loved child with the freedom of his whole home). Like the ancient heroes he shows no fear in the face of the wild things he encounters and he subdues them by the exercise of his own will. Though they linger in the magical wilderness for a time, neither Max nor Odysseus can be persuaded to stay there despite appeals and blandishments; they remain dedicated to their purpose. Each achieves a successful return to home and normality and is rewarded by the love of a faithful kindswoman. They regain their kingdoms.

Where the Wild Things Are is justly admired for its exquisite illustrations, its meanings which readers might make from the text and the pictures are that in his dream Max realizes he has the power to control his ‘wild’ emotions, understands that when he threatened his mother he had not ceased to love her. The wild things’ appeal to Max: ‘Oh please don’t go — we’ll eat you up — we love you so!’ echoes the earlier threat he made to her: ‘I’ll eat you up!’ and shows his awareness that the intensity of his anger was a function of the intensity of his love. The hot supper which his mother has left for him shows that she realizes this too. The possibility of such personal meanings constitutes a potent appeal for child readers. But part of the story’s enormous and enduring popularity is attributable to Max’s role as a hero who undertakes a successful quest and masters the wild things — and from that other, socially significant meanings emerge. Although he is no more than 4 years old, Max has learnt the trick of domination and is clearly a potential member of the patriarchy.

‘WE’LL EAT YOU UP!’ FOOD IN WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE

The conflation between food (especially sweet food) and love is well known. As Rosalind Coward suggests, there is “something about loving [that] reminds us of food, not potatoes or lemons, but mainly sweet things — ripe fruits, cakes and puddings.”[…] Despite cultural taboos against cannibalism adults often play games with children in which we pretend that we are going to eat them. These games typically involve blowing raspberries on the baby’s tummy, kissing, nibbling and sucking on their toes and fingers, growling and playing giants or monsters, as in “the monster’s going to eat you up!”. Adults understand the food rules and the way they can be bent but not broken. But children, unfamiliar with the way metaphors work, must find adults’ behaviour very troubling.

Carolyn Daniel, Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

NOTES ON ILLUSTRATION IN WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE

Maurice Sendak Finds His Style

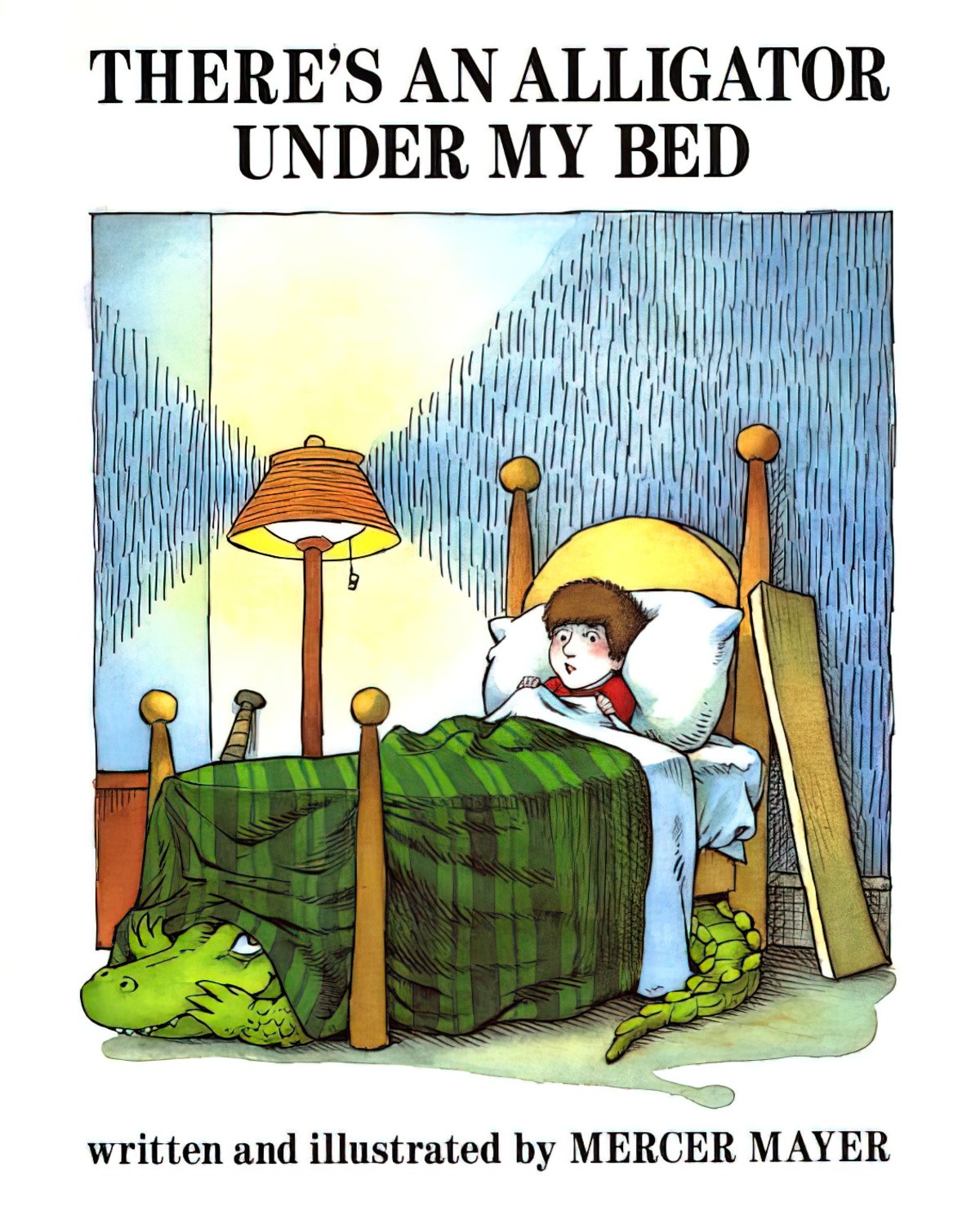

Illustrators struggle to find their styles; the style of Maurice Sendak’s early books is close to the commonplace conventions of most cartoons, and it seems that Mercer Mayer’s career as a picture-book artist would have been different if Sendak had never invented his Wild Things. And we do, certainly, tend to admire Sendak more for his original work in Where the Wild Things Are than for his more derivative work in earlier books and more in general than we do the generally derivative work of Mayer.

Perry Nodelman, Words About Pictures

Here is the cover of the first book Sendak ever illustrated. As you can see, the style is like many others of around that time:

Style, to me, is purely a means to an end, and the more styles you have the better […] Each book obviously demands an individual stylistic approach.

Maurice Sendak, The Openhearted Audience

By the time Sendak illustrated Wild Things, his style was distinctively his own. In order to get there, he did a lot of work. By the time he was 34, Sendak had written and illustrated seven books and illustrated 43 others, so his style was either going to develop or stagnate!

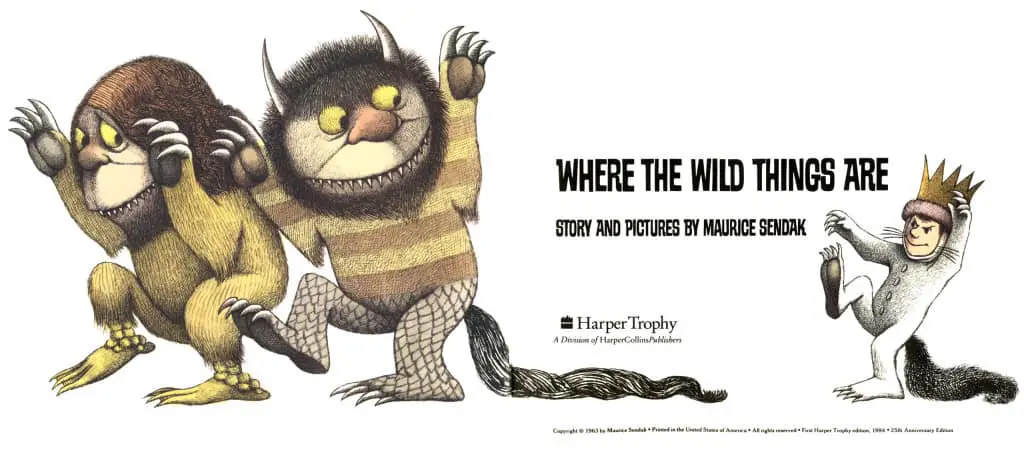

Character In Where The Wild Things Are

Sendak was a very influential illustrator, though it’s easy to forget, now, that once every single child depicted in picturebooks was blonde and cherubic. We still haven’t come far enough when it comes to illustrating non-white children, but it was Maurice Sendak who first started drawing pot-bellied, dark-haired, non-pretty looking children. In Outside Over There, the trolls look exactly like human babies, which added to the ‘disturbingness’.

Max of Where The Wild Things Are has a human face but the body of an animal (because of his wolf suit). The suit represents the way in which he gives over to his baser, animal instinct to misbehave. He must learn to enjoy being human again.

Color In Where The Wild Things Are

(Note that in order to see the colors properly, it’s necessary to look at the primary text.)

Writes Perry Nodelman in Words About Pictures:

The conventional meanings of colors are of two sorts: those, like the red of a stoplight, that are merely arbitrary and culture-specific and those that relate specific colors to specific emotions…the culture specific codes tend to be more significant in terms of their ability to give weight and meaning to the objects within pictures, but it is the emotional connotations that most influence the mood of picturebooks—the connections between blue and melancholy, yellow and happiness, red and warmth, which appear to derive fairly directly from our basic perceptions of water and sunlight and fire. Since such associations do exist, artists can evoke particular moods by using the appropriate colors—even, sometimes, at the expense of consistency”: Max’s room in Where The Wild Things Are is blue when he is first sent to it, a much more cheerful yellow after his visit to the Wild Things; and his bed changes from moody bluish purple to cheerful pink.

The Bedroom Colors

Other qualities of colors can also convey the emotional content of pictures. Consider the two pictures of Max in his bedroom in Where The Wild Things Are. Not only do the colors of the wall and the bed change, but their doing so changes the effect of the pictures as a whole. In the picture the pink of the bedspread is different from the purple of the bed, and both jar with the greenish yellow carpet; in the other picture everything is suffused with a warming yellow that brings the room together; the bed matches its spread and a bowl on the table. The unified calm of the picture contrasts mightily with the discordancies of the first one. Artists frequently use related colors to imply calm and discordant ones to suggest jarring energy or excitement.

Location of Character on the Page

In picture books, artists vary the location of their characters in order to inform us about whether we should be more interested in the action or in a character’s response to it. In Where The Wild Things Are, Max is at the edge of the picture as he sees the Wild Things for the first time, for at this point, what Max sees is what matters. But once we are familiar with the creatures, Max’s own action becomes more significant, and he moves to the center as he joins their wild rumpus.

Nodelman

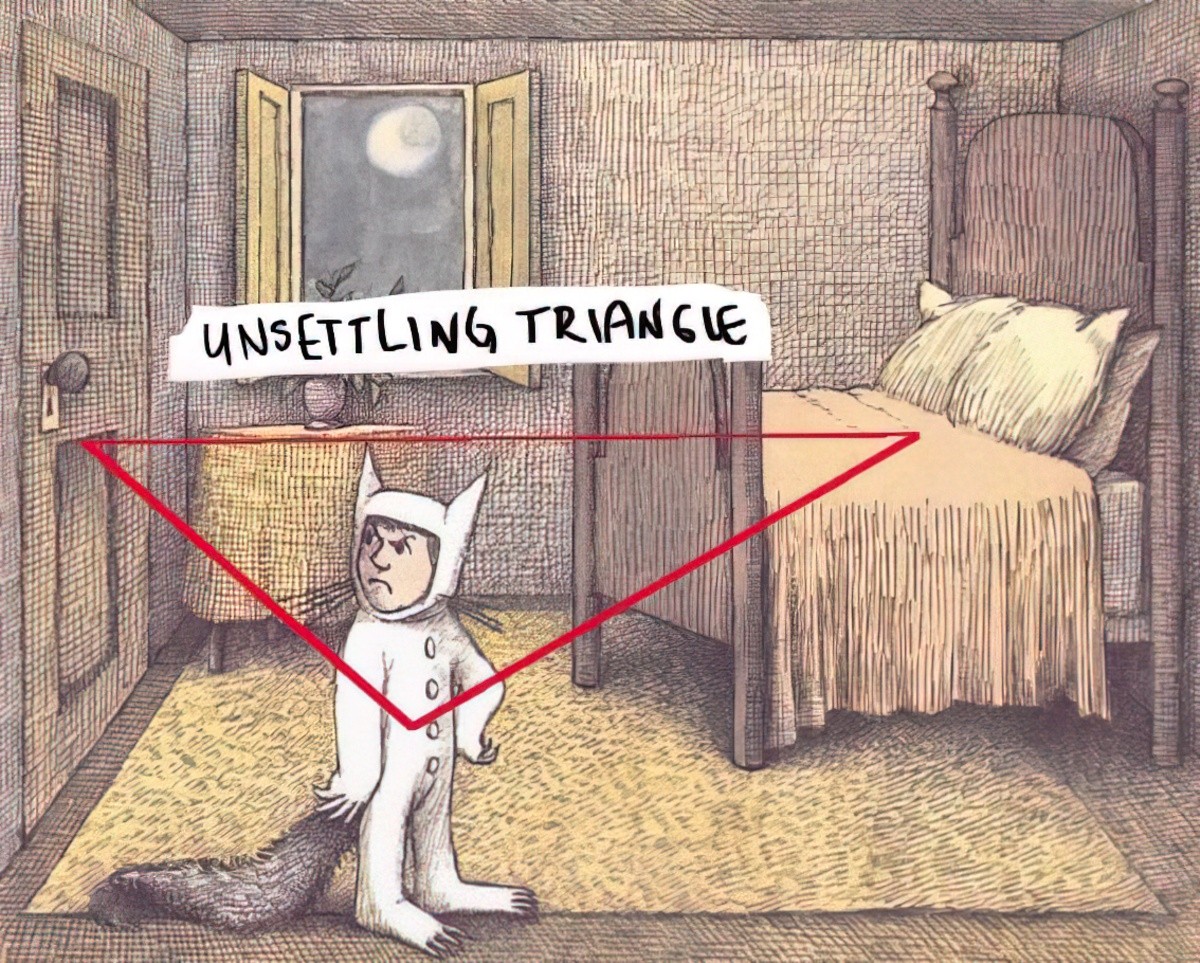

A more unusual use of central focus is the picture in Wild Things in which Max makes mischief by building a tent. The tent is on the left of the picture, Max on the right; the center is empty. Max faces out of the picture to the right, and his teddy bear faces out of the picture to the left; the focus is away from the center rather than toward it, and the mood is as unsettling as Max’s tantrum.

Nodelman

Use of Shapes In Where The Wild Things Are

Notice that Max’s wolf suit is the only patch of white, clearness on the entire page. This way, it stands out.

[W]hen the Wild Things make Max king the crescent shape of the moon is echoed by the curved backs and by the crescent shaped horns of the Wild Thing closest to Max. Furthermore, the curves of Max’s crown turn its spikes into more crescents, the position of the first Wild Thing’s legs and arms make them into crescents, many of the leaves of the tree behind Max are crescent-shaped, the ground has suddenly developed a semicircular rise, and the line formed by the tops of the heads of the group of Wild Things on the right forms an arch also. The rhythmic unity of this picture evolkes a much quieter moment than those depicted before and after it, both of which seem to put more emphasis on the points of crescents than on their roundness.

Nodelman

Another thing to note is that the pictures start off postcard size and gradually expand as the book progresses, filling the page as Max’s imagination opens up.

Perspective As Narrative In Where The Wild Things Are

Usually, the use of perspective to create focus is…subtle. In Where The Wild Things Are, for instance, Sendak takes advantage of perspective lines to focus our attention on the moon, which gradually develops more weight in the series of pictures in which Max’s bedroom changes into a forest. In the first picture, the moon occupies a point close to the vanishing point, but it is hazy, and the unsettling upside-down triangle made by Max, the door, and the bed focuses our attention on Max and his anger. In the next picture, the moon is more distinct from the background, while the heavily outlined trees make the bed and window stand out less. The original triangle has faded, but no definite focus replaces it, and the picture demands our attention to many of its elements: the more prominent moon, the trees as new and therefore automatically interesting, and still, if only because he is human, Max himself. In the third picture, the bed fades, and the trees lose their harsh outlines; only Max stands out. But the moon, now exactly in front of the vanishing point, demands some attention; furthermore, its whiteness echoes Max’s whiteness, so that a relationship between the two is suggested. The last picture in the sequence makes the relationship clear. Max, his back turned to us, is in shadow, and the moon, at the vanishing point, is the only really bright object left. As the focus of our attention and Max’s, it communicates the key meaning of the picture, the mysterious unreality traditionally associated with moonlight; it creates an atmosphere of freedom from restriction that might imply anarchy, of wonderful but potentially dangerous things about to happen. As a whole, this sequence of pictures shows how subtle changes in focus can make what is basically the same composition express different meanings. The pictures so economically move our attention from Max’s state of mind to the potential excitement of a moon-bathed forest that few words are necessary.

Nodelman

Light Source and Shadow In Where The Wild Things Are

Throughout Wild Things, depictions of the moon attract attention both to themselves and to the objects they cast light upon—usually on Max himself. But surprisingly, the moon is not the only source of light in many of the pictures in which it appears; Sendak invents other invisible light sources to make the objects he wants us to focus on stand out. When Max stands in his bedroom with his back to the moon, his front is lit from the left front; but when he turns his back and focuses his attention—and ours—on the moon, this apparent source of light in the front disappears and Max’s back is shadowed. Something similarly strange happens in Ida’s bedroom in Outside Over There: the light shining through the window causes the table leg to cast a shadow, but as the world outside darkens, the shadow remains. Perhaps […] this is Sendak’s way of telling us that all that happens here is a daydream that occupies only one brief instant.

Nodelman

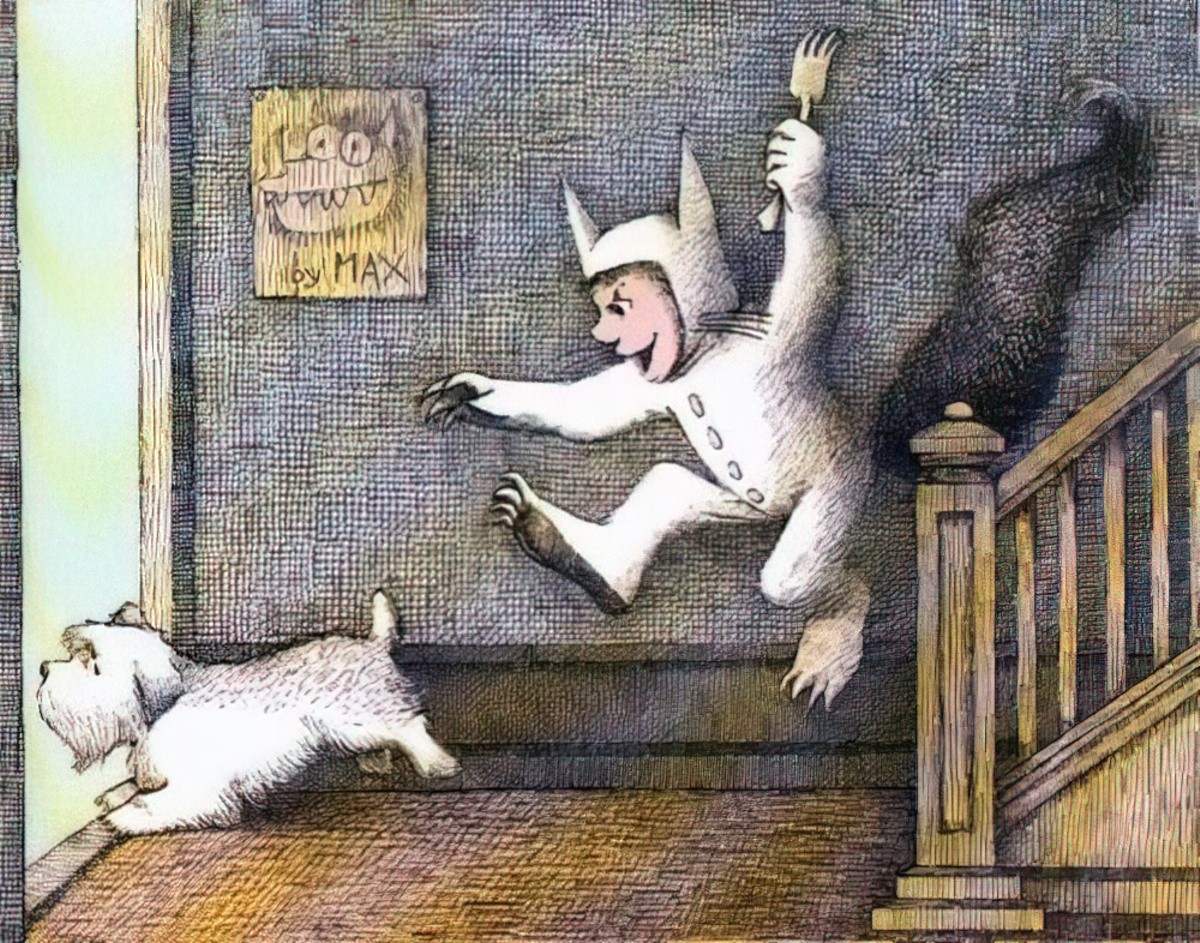

Movement In Where The Wild Things Are

Picture books are filled with pictures that show an action just before it reaches its climax. In Where The Wild Things Are, we see Max’s hammer about to hit the nail, Max in midair about to land on the dog, Max’s foot in midair about to stamp the ground. The few pictures showing Max with both feet planted firmly on the ground are the least energetic ones in the book; they either suggest that he is resting or else give him a strong, stable position of authority.

Nodelman

Shading to Convey Energy In Where The Wild Things Are

In Wild Things, Sendak implies various levels of energy by using two different sorts of shading. In the pictures of Max making mischief at the beginning of the book, the shading on the figure of Max is composed of hatching, disconnected lines all in the same direction, but the rest of the picture is shaded with crosshatching, which creates numerous small, enclosed, stable squares. The crosshatching holds the objects down; Max is clearly in motion, while nothing else is. As the forest grows in Max’s room and he calms down, his shading comes to consist of more crosshatching. Later in the book, during the wild rumpus, all the shading but that on Max is crosshatching, and he becomes more filled with crosshatching as the sequence goes on. That helps create a curious dreamlike stasis even in spirt of the exuberant action in these pictures.

Nodelman

For more on the illustration style in this book, see Holly Manns’ slide show.

Later Pictures In A Picturebook Become Context For Earlier Ones

More on the picture of the Wild Thing hanging on the wall at the end of the stairs:

[W]e come to understand the implications of Max’s joyous anarchy in the first pictures of Where The Wild Things Are more completely only when we see the picture that shows him alone in his room; the anarchy is now not merely fun but appears to have significant social implications. Furthermore, it is not until much later in the book that we may recalled the picture “by Max” hanging on the staircase wall in those earlier pictures and come to understand its implications: we learn that Max drew not just a monster but a creature he might visit in his imagination, and we understand how very much the place where the Wild Things are is indeed a product of Max’s imagination. The model airplane hanging over Mickey’s bed in the first pictures of In The Night Kitchen has a similar function. Such examples suggest how very much the later pictures in a book become a context for the earlier ones in re-readings. It is impossible to reread a book as we first experienced it.

Nodelman

STORY SPECS OF WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE

338 words

40pp

According to Sendak, at first Wild Things was banned in libraries and received negative reviews. It took about two years for librarians and teachers to realize that children were flocking to the book, checking it out over and over again, and for critics to relax their opinions.

COMPARE WITH

There is an uncountable number of texts which have been influenced by Wild Things. Also, Wild Things was part of a wider movement, influenced itself by texts which came before.

Harry the Dirty Dog is offered by Stephens as another example of a carnivalesque text in which a child character (in this case a dog) interrogates the established order, then returns home to safety.

Perry Nodelman compares Max to Peter of Peter Rabbit in his book Words About Pictures. Both Max and Peter have a wild side, and are punished for not behaving like proper humans. Peter Rabbit is, of course, ostensibly an animal, but note that it’s his human coat that gets him into all that bother in the first place.

FURTHER READING ON MAURICE SENDAK

- Maurice Sendak And His Editor Ursula Nordstrom: A Cautionary Tale from Awl

- Sendak Brothers’ Book, An Elegy, A Farewell from NPR

- Maurice Sendak Is Interviewed On The Colbert Report, SCBWI

- Where the wild things learn: Brooklyn school gets named after Maurice Sendak from Brokelyn

- The Key to Maurice Sendak’s Success With Children? His Contempt for Adults from Good

- Oliver Jeffers: Maurice Sendak’s Jumper And Me from The Guardian

- Maurice Sendak’s Little-Known and Lovely Posters Celebrating Books and the Joy of Reading from Brainpickings

- Maurice Sendak’s ‘Where The Wild Things Are’ Taught Us These 7 Vital Life Lessons from Caitlin White

- Maurice Sendak On Art And Art Making from LitHub

- Where The Wild Things Are at Stuff White People Like

“If there’s anything missing that I’ve observed over the decades it’s that that drive has declined,” said the 83-year-old author… “There’s a certain passivity, a going back to childhood innocence that I never quite believed in. We remembered childhood as a very passionate, upsetting, silly, comic business.”

Children’s books today aren’t wild enough, says Maurice Sendak, The Guardian

Once upon a more staid time, the purpose of children’s books was to model good behaviour… Seuss, Sendak and Silverstein ignored these rules.

The Children’s Authors Who Broke The Rules, New York Times

Notice how ‘people who break rules’ tend to be men. Anecdotally, I can tell you that women who break the picture book rules don’t tend to get their work published. Publishers wait for someone with a masculine name to come along before taking a gamble on him.

Monstrous Youth: Transgressing the Boundaries of Childhood in the United States

In Monstrous Youth: Transgressing the Boundaries of Childhood in the United States (Ohio State Press, 2022), Sara Austin traces the evolution of monstrosity as it relates to youth culture from the 1950s to the present day to spotlight the symbiotic relationship between monstrosity and the bodies and identities of children and adolescents. Examining comics, films, picture books, novels, television, toys and other material culture—including Monsters, Inc. and works by Mercer Mayer, Maurice Sendak, R. L. Stine, and Stephanie Meyer—Austin tracks how the metaphor of monstrosity excludes, engulfs, and narrates difference within children’s culture.

Analyzing how cultural shifts have drastically changed our perceptions of both what it means to be a monster and what it means to be a child, Austin charts how the portrayal and consumption of monsters corresponds to changes in identity categories such as race, sexuality, gender, disability, and class. In demonstrating how monstrosity is leveraged in service of political and cultural movements, such as integration, abstinence-only education, and queer rights, Austin offers insight into how monster texts continue to reflect, interpret, and shape the social discourses of identity within children’s culture.

at New Books Network

What We Talk About When We Talk About Books

What do children love most about books? Leaving their mark on inviting white spaces? Or that enchanting feeling when a book marks them as its own, taking them off to where the wild things are? Back in 2021, Elizabeth and John invited illustrious and illuminating book historian Leah Price to decode childhood reading past and present. The conversation explores the tactile and textual properties of great children’s books and debate adult fondness for juvenile literature. Leah asks if identifying with a literary character is a sign of virtuous imagination, or of craziness and laziness. She also schools John on what makes a good association copy, and reveals her son’s magic words when he wants her to tell a story: Read it!

For many years an English Professor at Harvard, Leah is founder and director of the Rutgers Initiative for the Book, and she tweets at @LeahAtWhatPrice. Her What We Talk About When We Talk About Books recently won Phi Beta Kappa’s Christian Gauss Award.

Sometime around the turn of the millennium, the concern about distinguishing between juvenile and adult books seemed to shift from moral panic about speeding up sexual maturity to worry about turning back the clock on what we now call adulting through the mainstreaming of young adult literature.

Mentioned in the episode:

- Patrick Mc Donnell, A Perfectly Messed-Up Story

- “Association copy”–e.g. Frida Kahlo’s goofily annotated and illustrated Works of Edgar Allen Poe.

- Mo Willem, We Are in a Book! (An Elephant and Piggie Book)

- Manners with a Library Book

- Dorothy Kunhardt, Pat the Bunny

- Erica Carle, The Very Hungry Caterpillar

- Peggy Rathmann, Ten Minutes Till Bedtime

- Maurice Sendak, Where the Wild Things Are

- Richard Wilbur, The Disappearing Alphabet

- Dr. Seuss, On Beyond Zebra!

- Miguel Cervantes, Don Quixote

- Charlotte Lenox, The Female Quixote

Recallable Books: what else should I read if I enjoyed this episode?

New Books Network

- (Leah) Francis Spufford, The Child that Books Built: A Life in Reading

- (Elizabeth) E. Nesbit The Railway Children: not to mention The Phoenix and the Carpet and Five Children and It

- (John) Wanda Gag, Millions of Cats: it’s The Road for cats…

- John also wrote a children’s book, back when his kids were tiny: Time and the Tapestry: A William Morris Adventure