The Electric Grandmother is basically a Twilight Zone episode for kids.

The teleplay (and a short story adaptation of “I Sing The Body Electric”) was written by Ray Bradbury, and was later remade by the Disney Channel as a full-length Made for TV movie called “The Electric Grandmother”.

TV Tropes

The Twilight Zone for a contemporary audience is of course Black Mirror. I wonder if Charlie Brooker watched “The Electric Grandmother” growing up, as well as The Twilight Zone. “The Electric Grandmother” reminds me very much of “Be Right Back“, in which a woman orders a synthetic version of her deceased boyfriend.

I’m not the first to have noticed this, and Charlie Brooker counts The Twilight Zone as one of his influences.

It took me a few minutes to place the father, played by Edward Herrmann, who later played the grandfather in Gilmore girls.

The friend who shared this via YouTube remembers The Electric Grandmother fondly, and hadn’t forgotten the songs. Apart from the songs, the most resonant scene, remembered long after the name of the story and the plot is forgotten, is the one where the grandmother squirts milk from her forefinger.

Every story needs a resonant scene like this — one which the audience remembers after details are long gone.

I believe it was the late Rosalind Russell who gave this wisdom to a young actor: “Do you know what makes a movie work? Moments. Give the audience half a dozen moments they can remember, and they’ll leave the theater happy.” I think she was right. And if you’re lucky enough to write a movie with half a dozen moments, make damn sure they belong to the star.

William Goldman

This Milk Finger scene resonates for several reasons:

- The audience hasn’t seen this exact thing before.

- Memory experts advise people to put dissonant things together in order to remember them. For instance, if you want to remember to buy cabbage at the supermarket, imagine the entire supermarket made out of hollowed-out cabbage. We can utilise this when telling stories, too. And next time you need to remember milk at the supermarket, maybe think of yourself squirting milk from your finger, like this scene from The Electric Grandmother.

- This milk finger scene is the first time the audience sees what The Electric Grandmother can do. Until this point, the electric version of the grandmother has seemed just like the dead one.

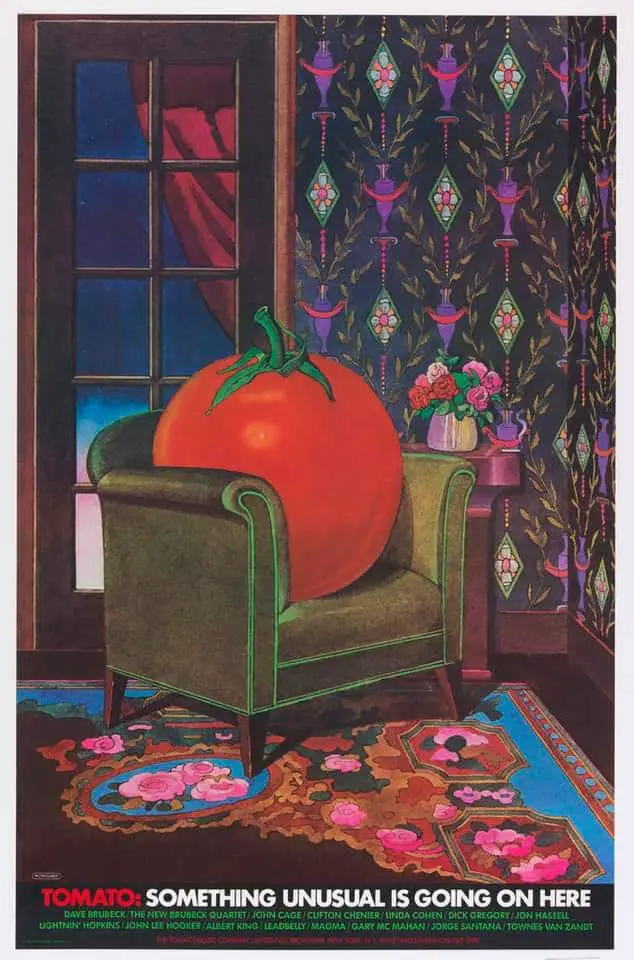

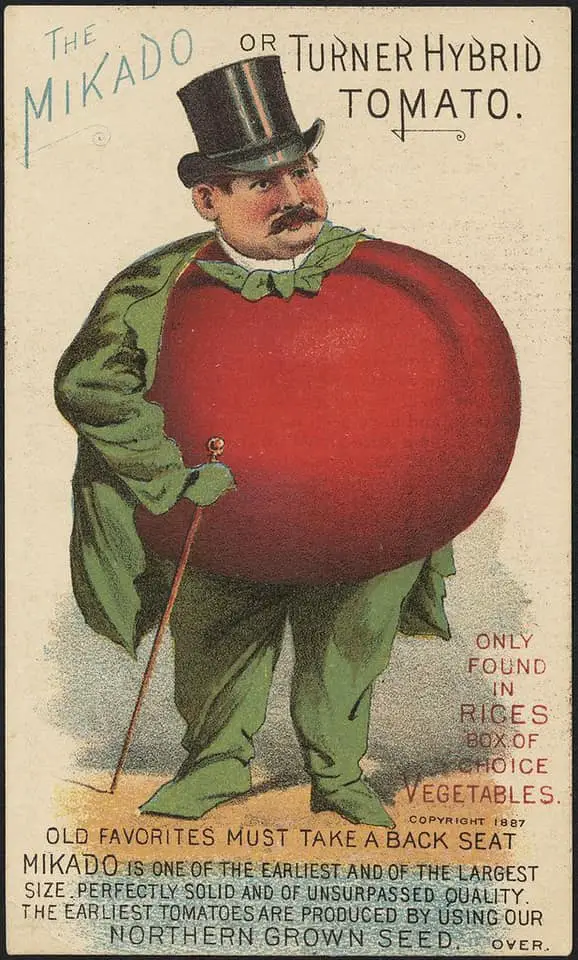

RESONANT IMAGERY IN STORYTELLING

When artists choose to illustrate a single narrative moment, they make a choice of lasting importance, because their illustration creates a memorable impression for an entire story, one that visually anchors an impression of that story in its reader’s memory. Illustration history is full of such memorable moments. In the illustration history of Grimm’s Tales, one image predominates, that of “Hansel and Gretel” beginning to eat the witch’s house.

In “The Musicians of Bremen” the dominant image is of the donkey, dog, cat, and rooster climbing onto one another’s backs and frightening off the robbers.

In “The Sleeping Beauty” the princess usually lies asleep, surrounded by thorny roses; in “Red Riding Hood” a little girl peeps at a wolf who is wearing her grandmother’s nightgown and nightcap. It is important to remember that at some point in the past not a single one of these images yet existed and no-one had yet decided which part of each of these verbal stories would be made visual. It is that fateful moment of decision in an artist’s mind that is in question.

Ruth Bottigheimer, “Illustration and Imagination”

Is there terminology writers use to describe ‘the part of a story which remains with the audience’ forever?

At Fiction Writers Review, Elizabeth Meyer writes of ‘strange objects’, which is a good term for this:

Strange objects, objects that exist beyond our expectations, do all the work of ordinary objects; but by making the imagination work harder, by requiring the reader to see beyond the everyday, they also create an even more thorough engagement with the text. In “Congress” by Joy Williams and “Sewing for the Heart” by Yoko Ogawa, bizarre objects play dominant roles. In both stories, strange objects serve to mesmerize the reader as well as the characters themselves. Their strangeness fixes our attention, drawing us with curiosity deeper into the narrative while also revealing more submerged themes within the texts and illuminating the characters around them.

Meyer has gone further than the object itself, linking it to what I’ve also heard described as the ‘symbol web’. Though I’m not sure the milk finger in The Electric Grandmother is especially symbolic. It’s just… weird and memorable. In literary work for adults, I would certainly expect the strange object to be linked to the symbol web.

Related to all this, David Lynch uses a term called ‘The Eye Of The Duck’ to describe a critical moment in film.

I’m not sure Lynch would describe the Milk Finger image in The Electric Grandmother as an example of what he’s talking about, but it’s the closest I’ve come so far to a description of these moments/images in a story which feel perfect, and perfectly memorable.

He used the phrase in an interview with the “Daily David”, in which Lynch talks to an audience about storytelling stuff. You can also see it on YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q2xNPsIm7_Y

Why does he call it that? Because when you look at a duck, you feel like its eye couldn’t be placed anywhere else on its body. The eye of the duck feels like it’s in exactly the right place.

Lynch compares film as a whole with the body of a duck and claims that every film has a scene that can be compared to the eye of a duck on a metaphorical level. The placement of the eye, the jewel, within a duck’s body is crucial because it would not make sense anywhere else. It “feels correct” and completes the overall appearance of the body. The very same thing applies to a film (the “body”) and a certain scene (the “eye”).

An eye of the duck scene is not necessarily readily identifiable.

The Eye Of The Duck is not always critical to advancing the plot forward. The insights they convey do not necessarily affect the story of the film to a great deal. Instead it affects the way the audience perceives the film. It’s a concept used by writers who don’t really believe in story structure. David Lynch has said that he eschews traditional story structure. These people (Chatman is another one) believes that an audience provides structure to a story if they need one.

(Others say that although David Lynch prides himself on having no structure to his stories, he actually follows story structure pretty conventionally.)

It will be the scene which sticks in your memory long after you’ve forgotten the rest. For me, an eye-of-the-duck Twin Peaks moment is the dancing dwarf in the red room, but I also remember the phrase, “It’s on the turn” to describe a piece of fruit (and use it often).

Lynch’s medium is film and TV, but Flaubert came up with a very similar phrase to describe ‘the exact word or phrasing’ in a text: le mot juste.

HOW TO COME UP WITH YOUR OWN EYE OF THE DUCK

Lynch advises storytellers to remain open to ideas. Sometimes something suddenly feels complete after a new idea, when you’d assumed it was finished before. Dive within. This ‘eye of the duck’ doesn’t come from the intellect but from intuition.

“Stay true to the ideas. If you love them stay true to them… Maybe some fish comes that is not part of this dinner. Put it away and save it for another time… If something needs to be said twice there’s a feeling, a knowing that it’s correct… Stay on your toes because a thing isn’t finished until it’s finished.”

This is important advice because sometimes, in this age of minimalism, writers are urged to cut, cut, cut. But sometimes, even if a scene exists purely for its aesthetic value — not because it adds obviously to plot, character, theme or setting — you should still keep it there.

See also: Unexpected Detail In Fiction