We are now in what’s known as The Third Golden Age of Children’s Literature. Naturally the First and Second Golden Ages came before.

What are the main differences between stories from the various Golden Ages?

First Golden Age of Children’s Literature: 1850-WW1

(Note: Some say the first golden age ended at the turn of the century. Others are more specific. Marina Warner gives the specific years of 1950-1920.)

Children’s literature can be as complicated, unsettling, and ideologically complex as any other kind of literature. Marah Gubar and others have demonstrated this with respect to Victorian children’s literature, but there remains a persistent misconception of “the golden age” of children’s literature as a period of regressive, escapist, and innocently naïve fiction for children.

Happily Ever After? Ambiguous Closure in Modernist Children’s Literature

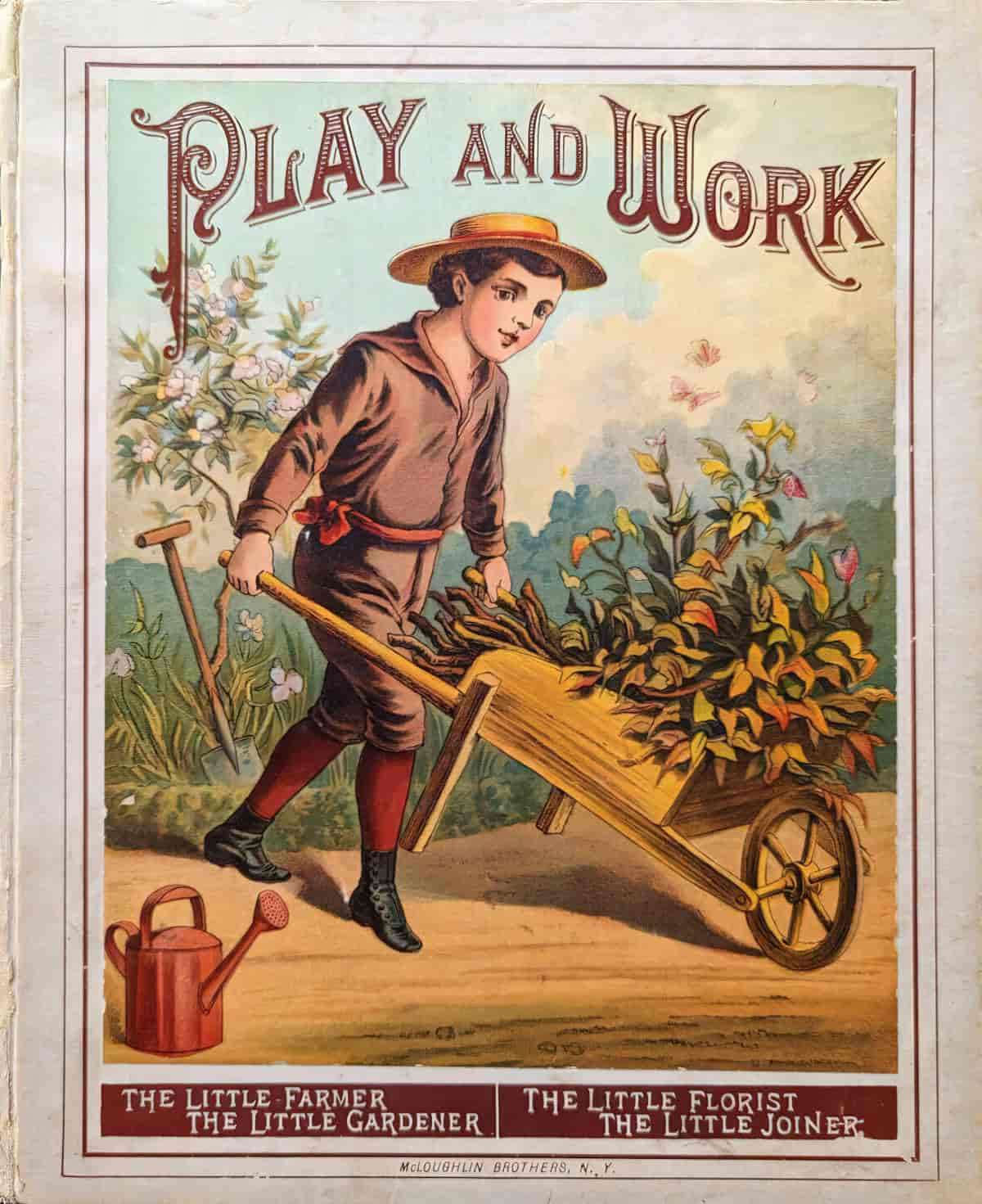

- Great writers would team up with great illustrators

- Industrial revolution led to advances in printing, affecting illustration

- The growing middle class increased their interest in education

- Didactic, often in a religious sense

- Reassurance that everything will turn out all right despite huge adversities

- Duty, self-sacrifice, no complaining

- Children do rather than think

- Outside all day with no supervision

- Proud of their class

- Patriotic

- Boys are stronger and bolder than girls

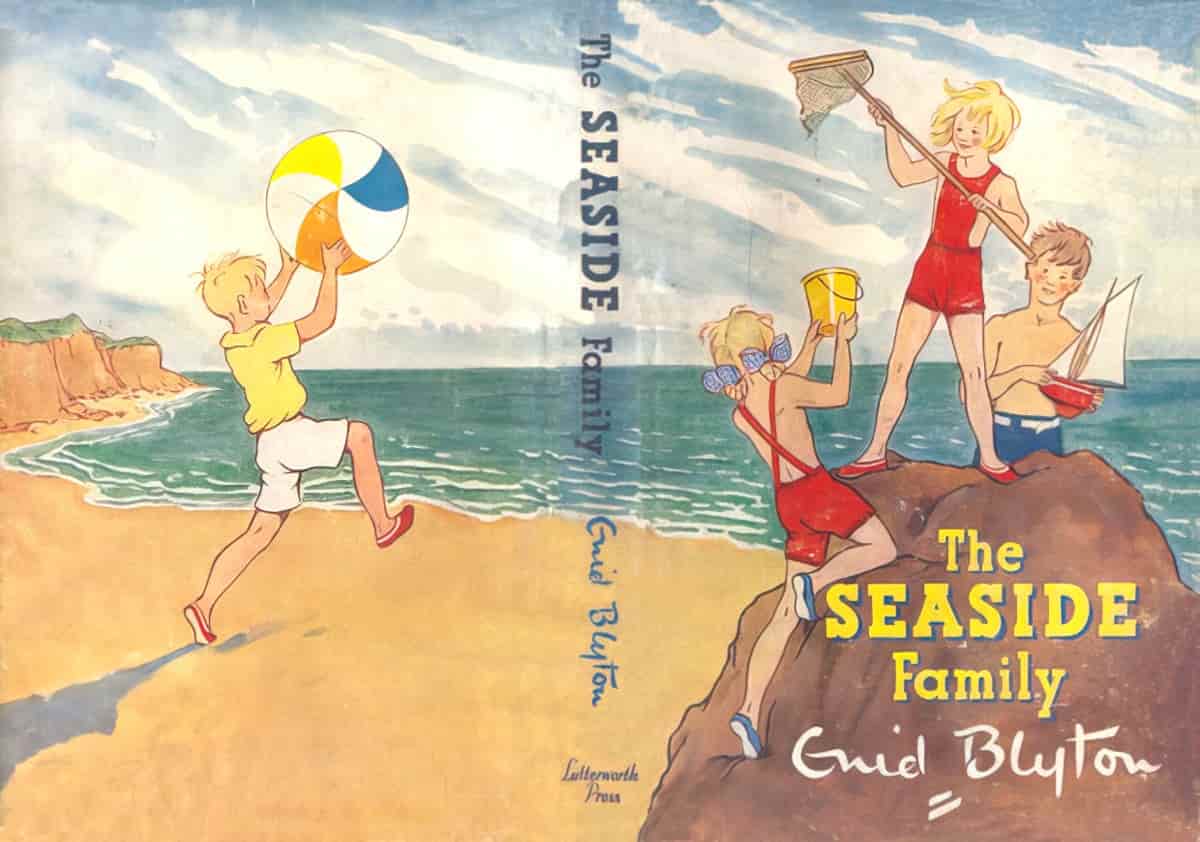

Enid Blyton’s children are required to be cheerful or else risk ostracism from the happy group. After all, the wars have ended; what could children possibly have to complain about? “The Caravan Family are spending their summer in beautiful, sandy Sea-Gull Cove. They are staying in their caravans, right at the edge of the sea, and it promises to be the best holiday ever! But poor, miserable Benjy Johns is with them. Will he ruin the children’s holiday, or can they cheer Benjy up and help him enjoy the sea and life in a caravan?”

Golden age children’s texts are actually far more complex and less idealistic than

Happily Ever After? Ambiguous Closure in Modernist Children’s Literature

they may initially appear. Many such texts set up a false expectation of Arcadian escape, while undermining the very fantasy world they have created by calling attention to its problems or its artifice. The fragmentation, existential anxieties, and narrative experimentation within these texts reflect the changing discourse of childhood in the modernist era.

If you think of some of the books which you may have loved in your own childhood — novels such as Little Women, say, or Charlie and the Chocolate Factory — and try to re-read them to your children, you quickly come up against concepts such as duty, self-sacrifice and not complaining which tend to be quite alien. Above all, the children in this First Golden Age do, rather than think. They are expected to be resourceful and resilient, proud of their class and country. When Nesbit’s Five Children time travel in The Story of the Amulet, they have no qualms whatsoever about telling Caesar how jolly marvellous Britain is — thus inciting him to invade us.

Adult nostalgia for the “Golden Age” of children’s literature … seems often to run in tandem with hand-wringing over declining standards of literacy and screen-locked, overstimulated juveniles. The feeling perhaps betrays a yearning for a halcyon era that never was. Those who consistently rate these books, in polls, as “all-time greats” or “essentials” do not necessarily also reason that outworn attitudes to disability, ethnicity, class and colonialism (not to mention old-fashioned modes of expression) create many barriers to contemporary children’s enjoyment.

Imogen Russell Williams

Examples From The First Golden Age

- Tom Brown’s Schooldays

- Little Women

- Adventure books for boys

- Alice In Wonderland

- Huckleberry Finn

- The Wind In The Willows by Kenneth Grahame — a classic example of a book from the Edwardian Era*, which lasted 1901-1910.

- The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett

- The Tale Of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter

- The Jungle Book — inspired the entire Boy Scout movement

- The Wizard of Oz

- E. Nesbit — Edith Nesbit’s work from the age of 20 to 40 was firmly in the tradition of the first golden age, but she suddenly started writing with a style far ahead of her time, helping to propel the West into the second golden age.

- The work of Frances Hodgson Burnett

- Anna Sewell’s Black Beauty — the first modern animal story

- Peter and Wendy — the first novel in which a group of ordinary children enter a magic world and have an adventure there. This is a great example of a children’s story preoccupied with death.

- Winnie the Pooh came right at the end of the first golden age. Critics tend to fall into two camps. The first camp say this series is not really for children because of the irony and cynicism which adults don’t think children can understand. The second camp argues the texts are too sentimental and naive for serious study.

*The Edwardian Era (1901-1910)

The Edwardian era was very short, and covers the brief reign of King Edward the seventh, 1901-1910. If you lived during this time you’d have been part of huge social upheaval:

- Women’s suffrage

- Workers’ strikes

- Agitation over empire

Particular tropes in fiction of this era reflect the feeling — in Britain, at least — that you were enjoying a garden party while surrounded by threats:

- Endless summers

- Pastoral and enclosed landscapes

- But these utopias are only snail under the leaf settings — not all is well underneath

Second Golden Age of Children’s Literature: 1950s-1970s

- Pictures and type saw further improvements.

- Improvements in colour printing technology made it possible to produce cheap multicoloured plates.

- From 1920 books could be produced in mass amounts in colour and literacy became sufficiently widespread

- Hans Christian Andersen became well known to English-reading children.

- Fairy tales began revolutionising with the study of folklore

- Hero legends are rewritten and simplified (bowdlerised) for children

- From mid 1900s chromolithography led to a craze for ornate gift books with a mediaeval design.

- Post 1960s literature often reflects society’s intense interest in child-rearing with a continuation of the child-only adventures which featured heavily in the first half of the 20th century alongside the return of the parent. There is now more emphasis on adult-child relationships, conventional and unconventional.

- We see a broader range of parenting styles and discipline. Stories explore power relations between adults and children.

- Before the 1960s, people rarely talked about children’s rights. However, children’s rights did not emerge suddenly in the 1960s. Along with other humanitarian and democratic values, they can be traced back primarily to the Romantic era, with the beginnings of legislation in Victorian times. The public school reforms by Samuel Butler and Thomas Arnold were followed by many attempts throughout the nineteenth century to improve the working conditions and education of lower-class children. These attempts to treat children humanely only started to really catch hold in this era. This is reflected in children’s literature.

- The 1960s and 70s saw the emergence of the new social realism for children which tackled previously taboo subjects e.g. divorce, child abuse. However, this didn’t replace other kinds of books. These new ‘social issues’ books simply existed alongside. Sheila Egoff called these new books ‘the problem novel’.

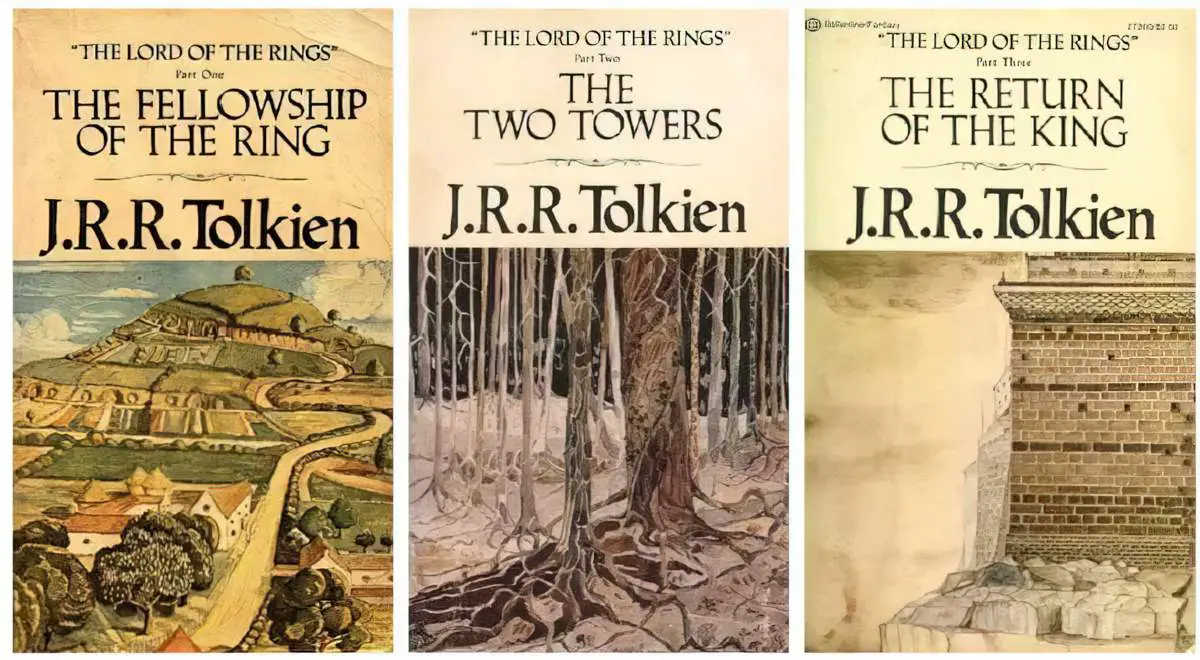

The Second Golden Age, which fed the imagination of the baby boomers, ran roughly from the 1950s to the 1970s, and is quite different in that it reverberates with a new, global moral consciousness. It portrayed the big struggle between good and evil — most famously in Tolkien — as an absolute struggle, and it did so in the wake of the Second World War. To grow into adulthood aware that someone, somewhere, can destroy the world with a nuclear bomb, does tend to have a profound effect on the imagination. To also discover that atrocities like genocide were carried out because a populace did not question authority is also to understand why subversive authors such as Roald Dahl, Judith Kerr and Maurice Sendak became so popular.

Amanda Craig

Maria Nikolajeva writes that post-WW2 children’s literature (which includes both the second and third golden ages) is different from what came before in that it has ‘started subverting its own oppressive function’. What does this mean? Well, one of the main functions of children’s literature (and also gay literature, feminist literature and so on) is to explore the power differential between different groups of people in society. Children are an ‘oppressed’ group due to their age and powerlessness. Earlier children’s literature was almost always written from an authoritative point of view by an unseen narrator filling in the blanks for less experienced children. In modern stories for children, the children’s writer often takes the part of the child.

Children’s literature starts to be a bit more subversive. Some critics have argued that all children’s literature is subversive by definition (e.g. Alison Lurie in her book Don’t Tell The Grownups), but at this stage of evolution, some books are subversive while others confirm rather than interrogate the idea that adults have (and should have) all the power.

According to Leonard S. Marcus, a historian of children’s literature, when public libraries began admitting children in the early part of the century, librarians ”tried to move children’s literature away from the religious, moralistic tone of the previous century. Didacticism was a dirty word. They’d talk about the art of the book, as opposed to the lessons a book could teach.” The rise of progressive education and the influence of European artistic modernism further shifted the focus of children’s books toward aesthetic and intellectual experience. The Depression slowed the trend, but by the time Seuss came along, a revival was under way that accelerated during the war, when toy production was curtailed and books picked up the slack.

Sense and Nonsense, NYT Magazine

Examples From The Second Golden Age

- Millions of Cats

- The Little Engine That Could

- Babar

- Madeline picture books, e.g. Madeline And The Gypsies by Ludwig Bemelmans

- Curious George

- The Cat In The Hat and other Dr Seuss books (“Dr. Seuss boldly resisted the tendency, in evidence since at least the Victorian era, to sentimentalize childhood, to project idealized images of innocence and wisdom that have little to do with what actual children are like.” A.O. Scott.)

- Where The Wild Things Are

- Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?

- The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle

- Corduroy

- The Polar Express

- If You Give A Mouse A Cookie, the first book read by Reading Rainbow

- Tom’s Midnight Garden (1958) by Phillipa Pearce

- Chrestomanci books by Diana Wynne-Jones, who combines fantasy with modern social issues

- Green Knowe books by Lucy M Boston

- The Changes Trilogy by Peter Dickinson

- The Midnight Folk by John Masefield

- Wolves of Willighby Chase by Joan Aiken

- Eva Ibbotson

- Enid Blyton

- Swallows and Amazons series by Arthur Ransome

- Noel Streatfeild

- Hilary McKay

- Anne Fine, social realism

- Fiona Dunbar

- Cathy Cassidy

- Anthony McGowan

- Francesca Simon

The Third Golden Age

I’m yet to jot down a more comprehensive post about this, but for now, it’s interesting to take a look at how books from the Second Golden Age are adapted for screen. This tells only a sliver of the fuller story, but take a look at the following paragraph, which sums up in a nutshell how the ‘plucky, curious’ children of yesteryear are now ‘melancholic’ (in a way that Dr Seuss himself may not approve):

JoJo, the reluctant hero of Whoville, has become that archetypal Seuss character — the dreamy boy whose parents worry that he thinks too much. But by Seussian standards, the problem may be that he feels too much. Instead of a plucky, curious hero of the imagination, he’s a melancholy fellow who complains, in a duet with Horton, that he’s ”alone in the universe.

A.O. Scott

More generally, American culture is having a big impact on the children’s literature produced in other countries, especially the other English speaking countries. Dan Hade’s talk on this topic: Branding And The Impact Of The American Export

What Will The Fourth Golden Age Bring?

We’re just coming out of a period of dystopia. Publishers are saying they never want to read another grim world because they’ve read too much of it. Now, that’ll partly be because they’re living in one. So I predict a return to hygge. To the comforting and cosy — genuine utopias rather than apparent utopias.

Publishers of young adult literature probably won’t have as much patience with the anti-hero either, unless that anti-hero is a girl. (We’ve not seen many of those, and she wouldn’t remind everyone of Trump.)

Remember Enid Blyton? The healthy kids (who don’t need Obamacare), the safe adventures, the celebration of imagination. We’ll see a return to The Second Golden Age Of Children’s Literature but without the racism and sexism.

That’s because around the world, writers, especially children’s book writers and illustrators, are left-leaning people. So a Trump Presidency won’t change the overwhelmingly left-leaning ideology which shines through in children’s books these days.

However, another way of depicting hygge is to create nuclear families in which the apron-wearing mother stays home and the father goes out to work — men saving the world, in other words. We’ll see those, too. Mad Men for toddlers.

#WeNeedDiverse Books

Trump’s racism and sexism may actually lead to better representation in children’s books, because Trump’s leadership will lead to the widespread use of language we all understand to talk about these things. Trump will make sure we all know the true meaning of misogyny, backlash, sexual assault, false equivalence, and what racism really looks like.

In short, no thinking person looking at America can plausibly deny that racism and sexism isn’t a thing, and those who wonder how we got to here might start taking a closer look at the influence of children’s media.

Fantasy vs Realism

Traditionally Britain has been the home of the most excellent children’s fantasy, but we’re about to see that matched well-and-truly by America, who has always been better at realism. We may see a lot of science fiction too, because it’s somewhat comforting to be transported off the Earth even if it is only by book.

We’ll also see surrealism, with quiet digs at the state of the world which only the adults in a dual audience readership will fully appreciate. Bully cats with hair like Donald Trump, that kind of thing. Trump will create a brand new literary trope. He may even cause a comeback of aptronyms (symbolic names).

There are common wish fulfilment fantasies in children’s literature, and one is ‘to be bigger than one’s enemies’. We’ll see quite a bit of that from both right and left leaning authors.

Header illustration: Bird Biographies A Guide-Book for Beginners by Alice Eliza Ball (1867-1948) Illustrated by Robert Bruce Horsfall (1869-1948) New York Dodd, Mead and Company, Inc., 1923 (goldfinch)