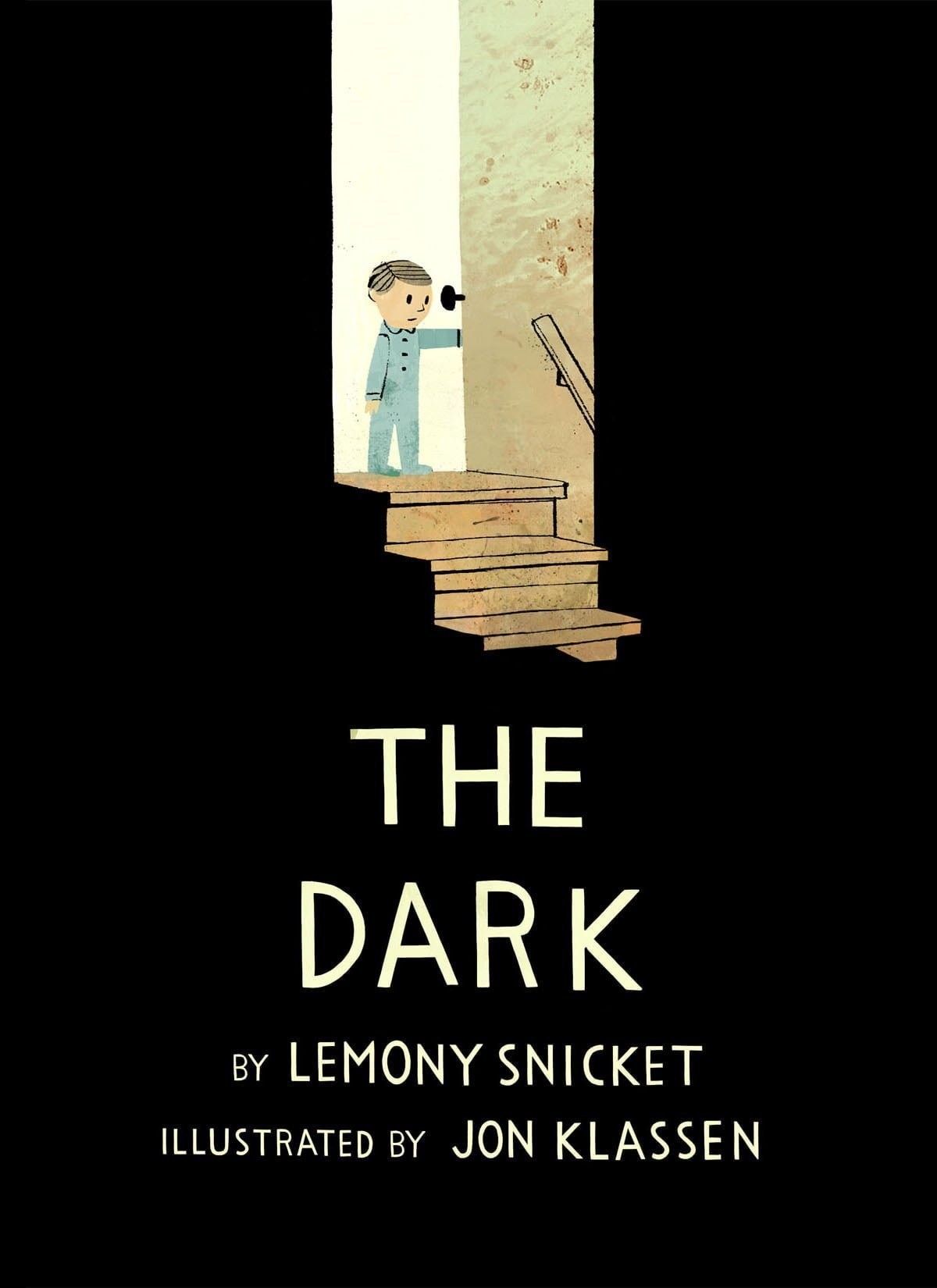

The Dark is a picture book written by Daniel Handler, illustrated by Jon Klassen. A boy faces his fear of the dark in an archetypal dream house.

WHAT HAPPENS IN THE DARK?

Shortcoming/Need

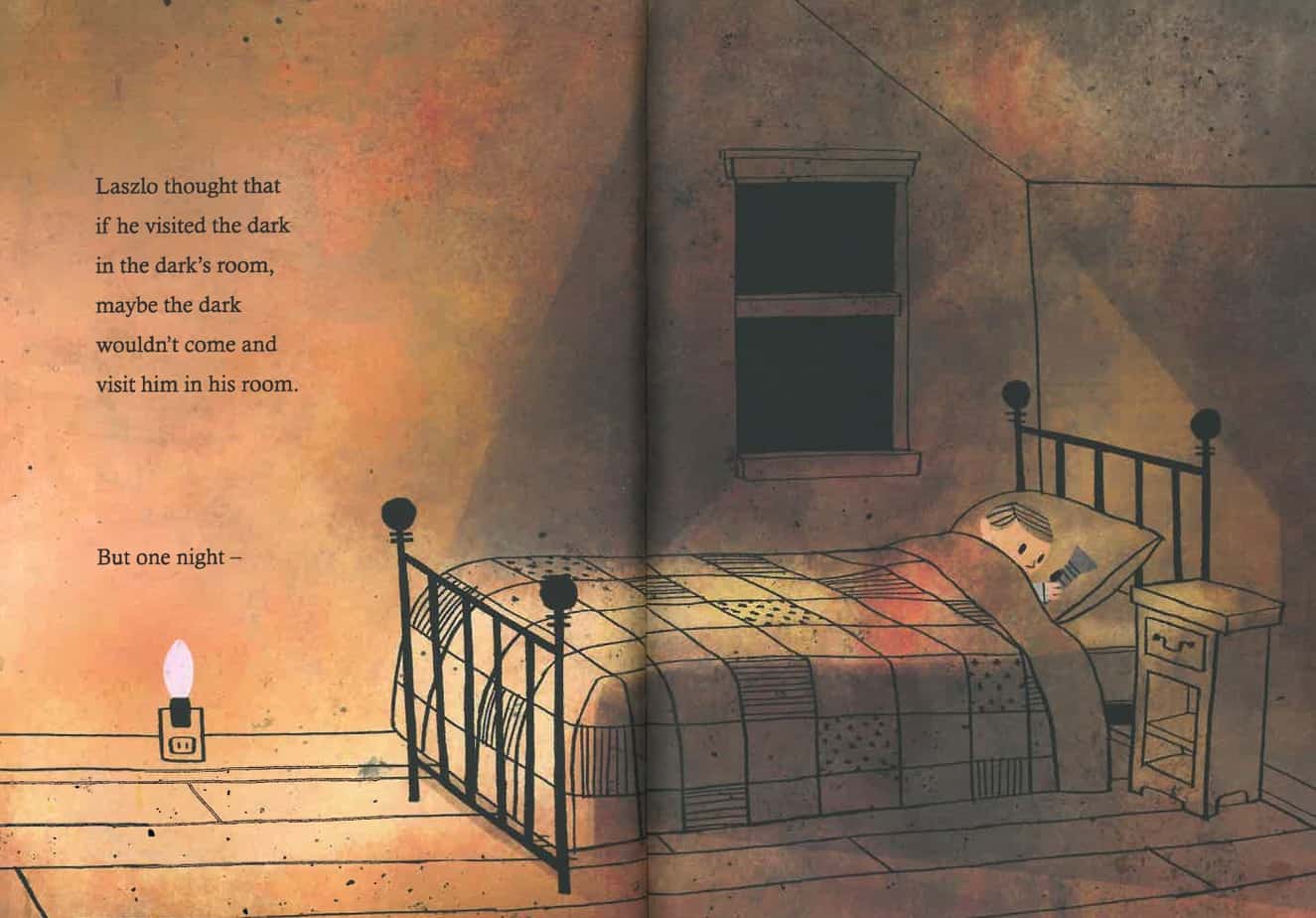

Psychological Shortcoming: “Laszlo was afraid of the dark.”

In children’s books, characters don’t need a moral shortcoming. (In other words, a child character doesn’t have to be treating anyone else badly in order for us to find them a sufficiently interesting and engaging character.) This boy is the Every Child.

Desire

On the first page we can see what Laszlo desires: He is playing with his toy cars in peace and solitude on the floor, so he obviously wants to continue doing that without being afraid of anything.

Opponent

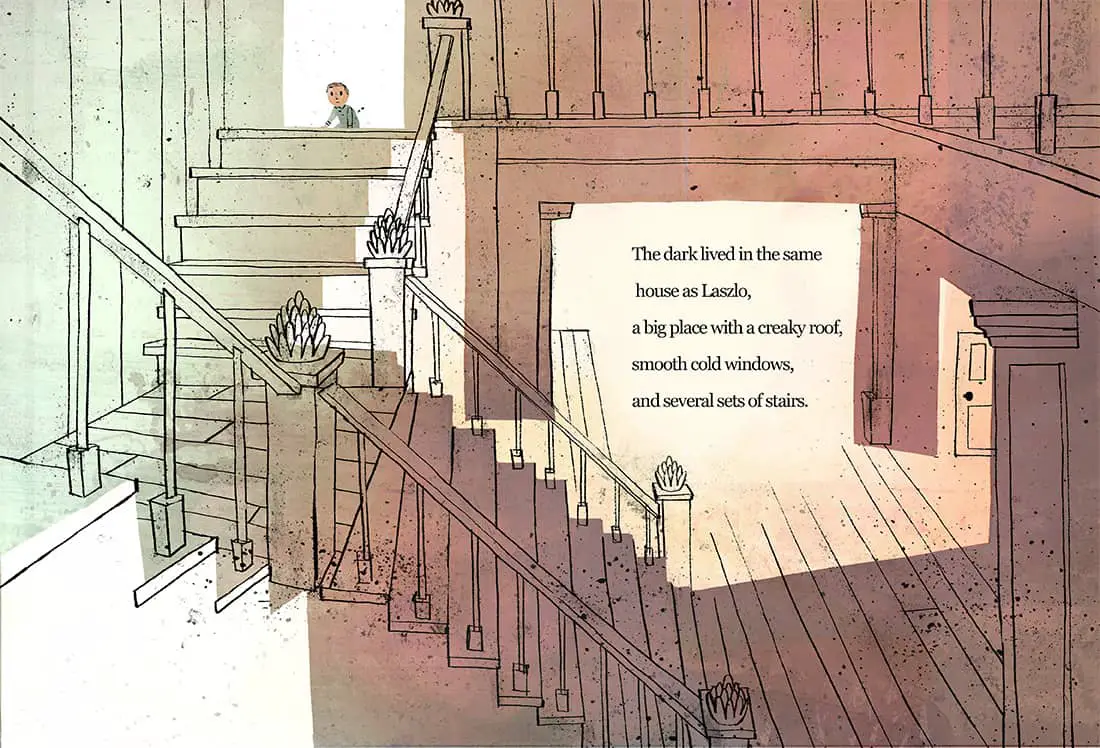

The Dark. “The dark lived in the same house as Laszlo”. Normally the opponent has to be another human or monster, but here the dark is personified, and might as well be a monster: ‘Sometimes the dark hid in the cupboard’. Daniel Handler spends quite a bit of time describing this monster and what it does.

Plan

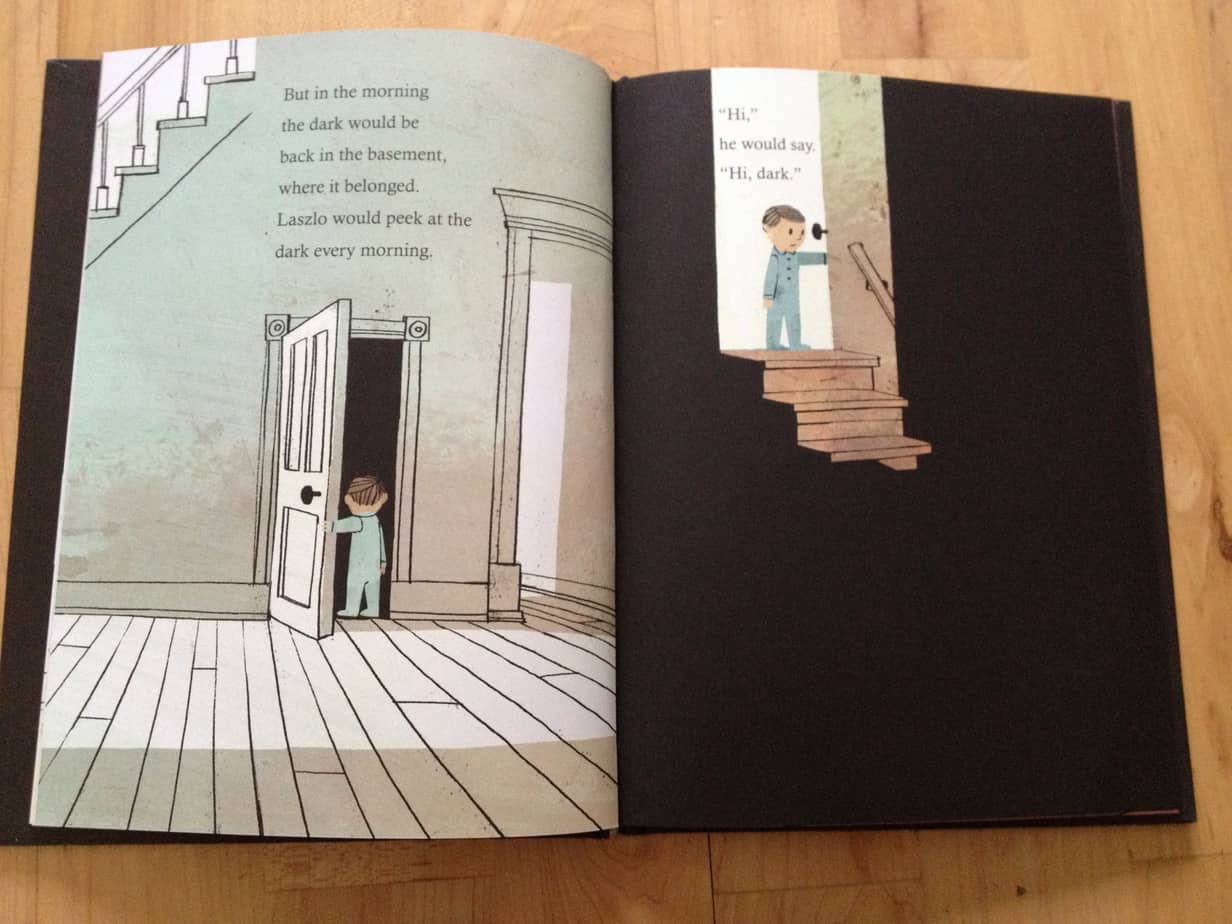

Lazlo’s trick for keeping the dark out of his bedroom is saying hello to it during the day.

Until the phrase ‘But one night’ the entire book is written in the iterative. Now we see the switch to the singulative.

Big Struggle

But when the bulb on the night-light burns out (we assume at this point), the dark does come into his room. The dark challenges Laszlo to visit it in the basement, which requires a scary trip down several flights of stairs. (Why he doesn’t just turn that torch on and use it as his night-light I’m not sure. I don’t think we’re meant to think that’s a possibility, though I have to admit it bothers me some — I think it’s a minor shortcoming in the plot.)

Anagnorisis

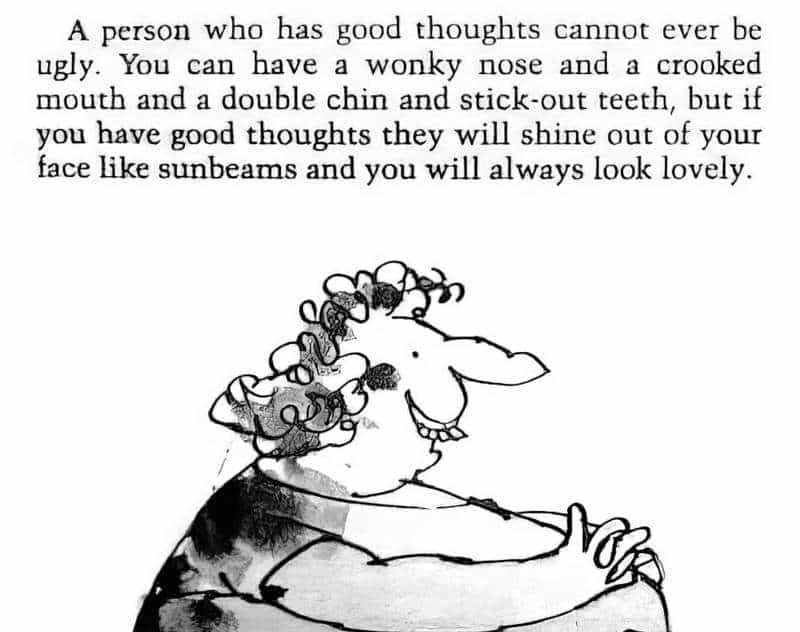

Laszlo’s anagnorisis comes in the form of a lecture, delivered by the author, meant for the young reader. There’s a very Roald Dahl feel to it, because Dahl used to do the same thing (for example in The Twits, when the reader gets a — rather hypocritical — lecture about not judging people based on what they look like):

In The Dark we have:

You might be afraid of the dark, but the dark is not afraid of you. That’s why the dark is always close by.

Young readers are then told that every scary thing with dark insides is actually necessary and useful and, ‘without the dark, everything would be light, and you would never know if you needed a lightbulb’, which is of course the far more humorous thing to say rather than, ‘without the dark you wouldn’t get a good night’s sleep’, and is very Daniel Handler.

We assume Laszlo has achieved this revelation on his own without the help of a narrator, and now the open drawer in the basement looks like a smiling face. He has realised there is nothing at all to be afraid of.

The dark can be kind, helpful even.

The Dark, written by Lemony Snicket and illustrated by Jon Klassen, shows us the dark through Lazlo’s eyes, which at first is scary and menacing. But through the shadowy illustrations and the lovely one page monologue in the middle of the book, we realize that we need the dark, and by the end, we fall in love with the dark’s generosity.

Nerdy Book Club

New Situation

‘The dark kept on living with Laszlo but it never bothered him again.’

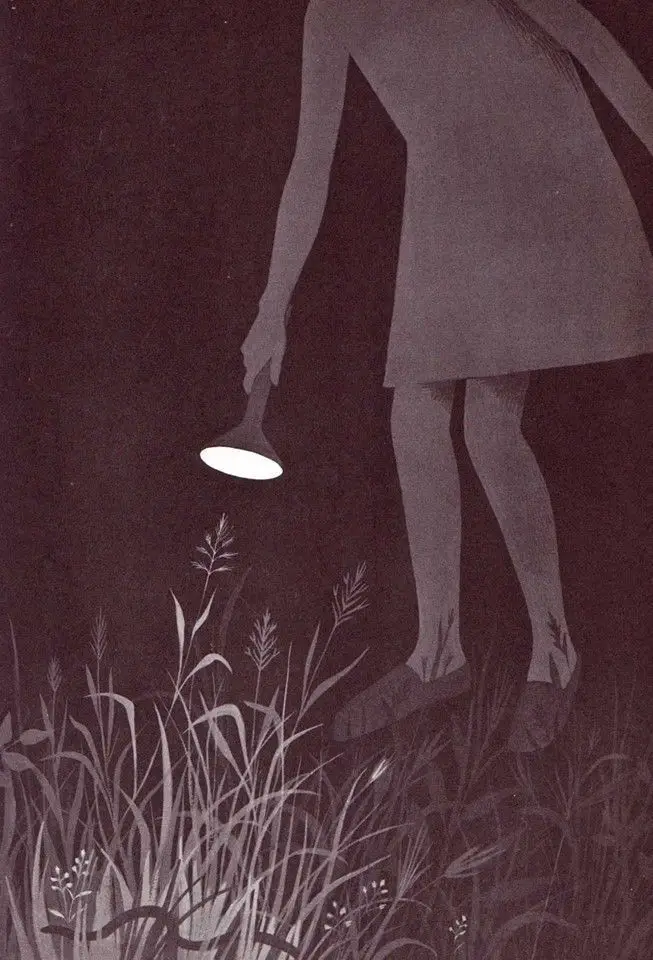

We even have the very same image bookending the story — the one where he’s playing with his toys on the floor. But this time the sun is in a slightly different place and Laszlo doesn’t look worried. Also, he no longer feels the need to carry a torch everywhere. This small detail shows that he has now overcome his fear of darkness.

Symbolism

Darkness

Darkness is of course symbolic throughout the history of literature and folkore and everything that came before. Below is a beautiful excerpt illustrating the dark in words by Joyce Carol Oates:

The house looked larger now in night than it did in day. A solid looming mass confused with the big oaks around it, immense as a mountain. The barns too were dark, heavy, hulking except where moonlight rippled over their tin roofs with a look like water because of the cloud shreds blowing through the sky. No horizon, solid dark dense-wooded ridges like the rim of a deep bowl, and me in the center of the bowl. The mountains were only visible by day. The tree lines. By night our white-painted fences and the barbed wire fences were invisible. In the barnyard, the humped haystack the manure pile, I wouldn’t have been able to identify if I didn’t know what they were. Glazed-brick silo shining with moonlight. Barns, chicken coop, the sheds for the storage of machinery, much of it old, broken-down and rusted machinery, the garage, carports—silent and mysterious in the night. On the far side of the driveway the orchard, mostly winesap apples, massed in the dark and the leaves quavering with wind and it came to me maybe I’m dead? a ghost? maybe I’m not here, at all?

from We Were The Mulvaneys

Fear of the dark is at its peak in early childhood, between the time we first learn of the daily dichotomy and the age at which we can logically comfort ourselves that the dark is simply the absence of light; no more, no less.

It’s that in-between period of literature that seeks to reassure rather than scare. There are no monsters here; just nothingness.

The House

As far as picture book houses go, this is a castle rather than an inviting, warm home. The floors are bare. Hard surfaces everywhere. It’s the oneiric house of Gaston Bachelard’s dreams (The Poetics of Space). Of course a house like this needs a cellar. A story like this needs a cellar, because cellars are always dark. From other stories we have learnt to be afraid of cellars — murders and criminals and all sorts can be found in a cellar, or at least suspected, and even when you take a torch down there, the place is still cast mainly in shadow.

(Interestingly, my version reads ‘flights of stairs’ rather than ‘sets of stairs’. Flights definitely feels nicer to me. Is ‘sets of stairs’ an Americanism?)

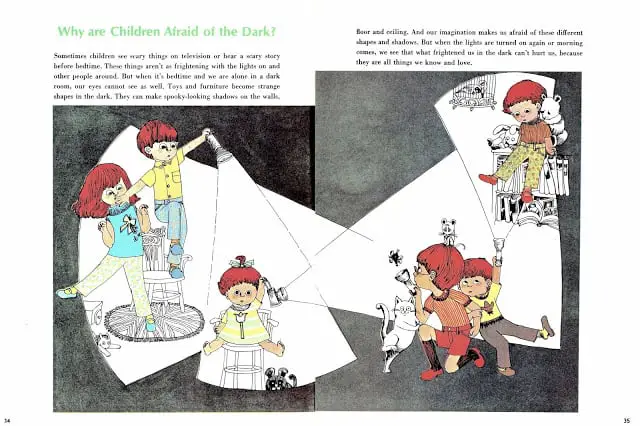

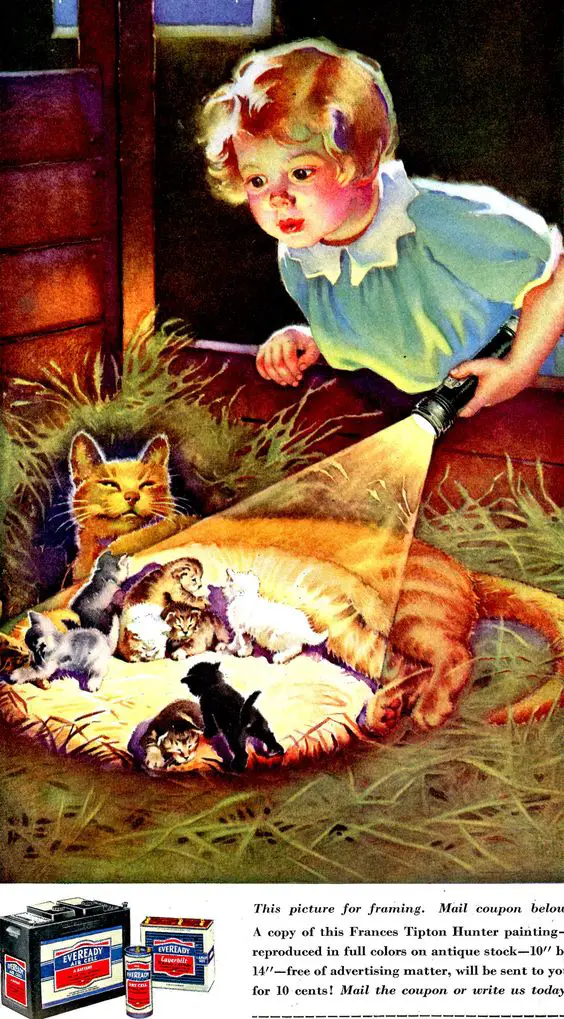

The way Jon Klassen divides his interiors into shapes and segments reminds me of some illustrations from the 1960s. Klassen uses shadow to create an extra layer of shapes, but the basic bones are somewhat similar.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION

Illustrators have many different ways of illustrating the dark. For other examples, see my post Illustrating The Dark.

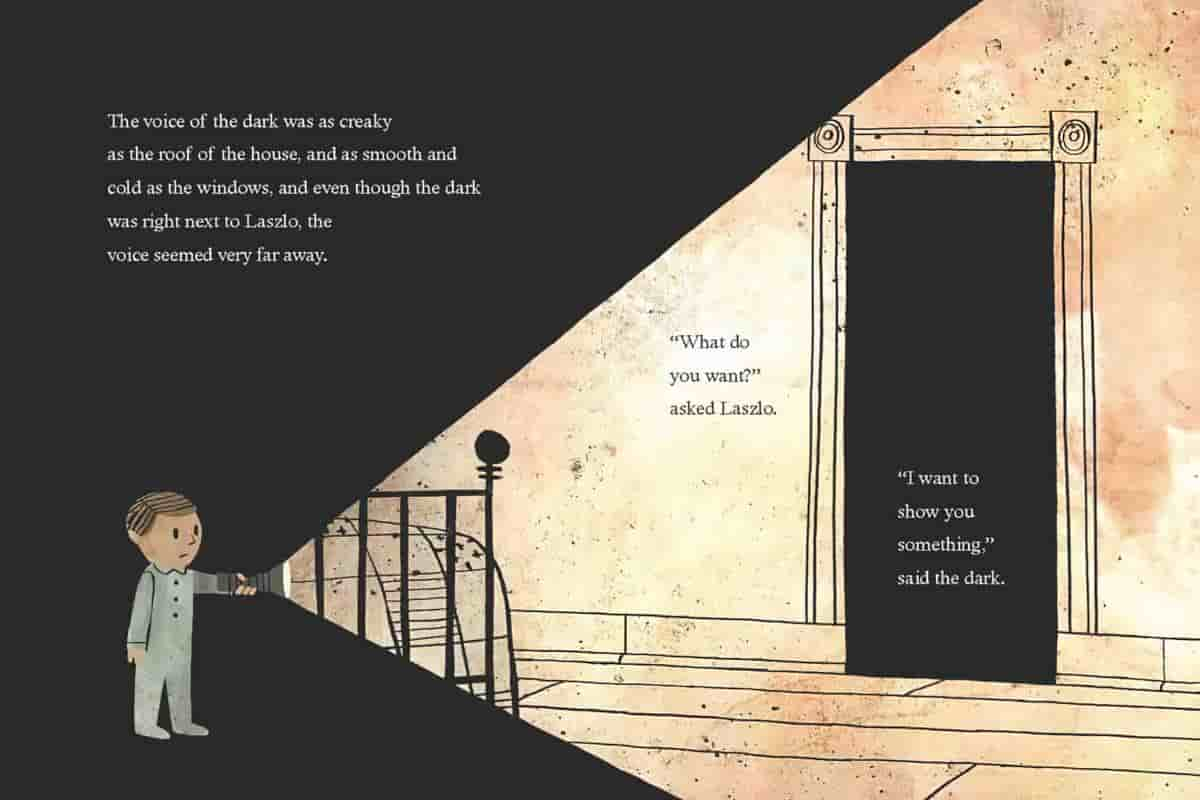

Geometry

Many modern books include plenty of white space — white is the neutral choice. But where black is chosen as a fill, the effect is dramatic. Here, of course, the black simply equals darkness. These areas of flat blackness emphasise the geometry of the pages. Here we have a rectangle and a couple of triangles, formed by the light from the torch. The triangles themselves almost form a monster’s mouth, with the bed-end resembling a grille of teeth. The effect of these strong, geometrical shapes is to complement the ‘cold windows’ and hard surfaces of this huge, unwelcoming house, which in real life might be nothing of the sort; this is the dream house of a little boy, and when you’re little, your house always seems much bigger in your mind.

This kind of geometry really is well-suited to the horror genre in general.

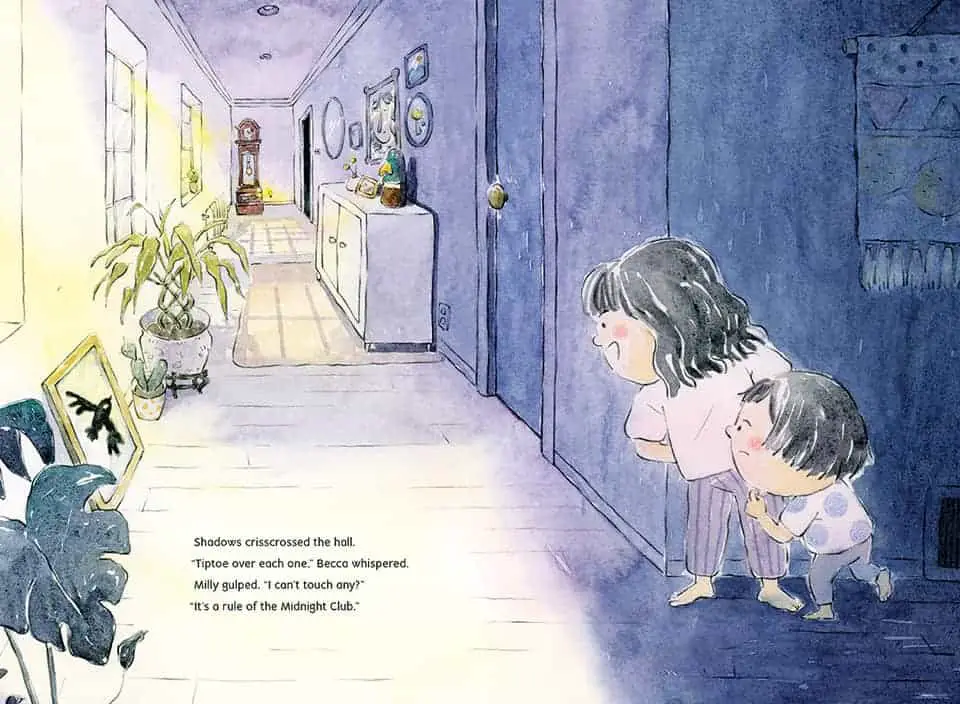

Shadow

The verso image below includes a couple of interesting shadow. We can’t see what is casting the shadow in the foreground. Likewise, we don’t know exactly where that rectangle of light is coming from down the hallway. (We do know it’s from Lazlo’s bedroom, but we can’t see the bedroom.) All of this ‘off-the-page’ lighting lets us into Lazlo’s fear.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

It creeps all over the house.

I find it hovering in the dining-room, skulking in the parlor, hiding in the hall, lying in wait for me on the stairs.

The above is an excerpt from the feminist short story from 1892, The Yellow Wallpaper. Charlotte Perkins Gillman inverted the usual trope of the dark, gothic house and applied horror symbolism to yellow, a colour most often associated with sunshine and happiness. The attic at the top of this particular haunted house is an example of a well-lit room, which is quite unusual in horror. Then again, the author isn’t writing a straight horror story; she is writing an allegory for postpartum depression, pointing out how horrifying the condition can feel when you’re in it. She’s inverting the very hauntedness of the house, saying it’s not the house that’s haunted at all; it’s the people inside the house.

MORE

A Brief History Of Home Lighting

An ignominious and unexpected burden to his family, Paddy, as [Lafcadio Hearne] was then known, was reared in the prosperous Dublin home of his great-aunt Sarah. “His mind,” in the words of one of his biographers, was “dominated by horror from an early age.” He had a crippling fear of the dark, which was treated by putting him to bed every night in a pitch-dark room that was locked from the outside.

Why Lafcadio Hearn’s Ghost Stories Still Haunt Us

SEE ALSO

The Dark is about fear, but some children’s books focus more on the excitement of prowling around the house at night.

Exhausted from their midnight expedition, Milly is ready to head to bed, but not before she remembers the club’s most important rule: The Midnight Club must be a secret! The sisters quickly clean up before settling into bed. But they might have left a few clues behind …

Fear of the dark doesn’t end with childhood. Stories for adults make equal use of the dark, or rather, what happens under its cloak.