Home is important to all of us and perhaps even more important to young readers. This is why the mythic journey when it occurs in children’s literature is more commonly known as the home-away-home story — unless a child moves house at the beginning of the story they most often explore alone for a while then return to the cosy safety of home.

The Tidiness Rule

Cosy houses in story need to be tidy but not too tidy.

Hominess is not neatness. Otherwise everyone would live in replicas of the kinds of sterile and impersonal homes that appear in interior-design and architectural magazines. What these spotless rooms lack, or what crafty photographers have carefully removed, is any evidence of human occupation. In spite of the artfully placed vases and casually arranged art books, the imprint of their inhabitants is missing.

Home: A short history of an idea by Witold Rybczynski

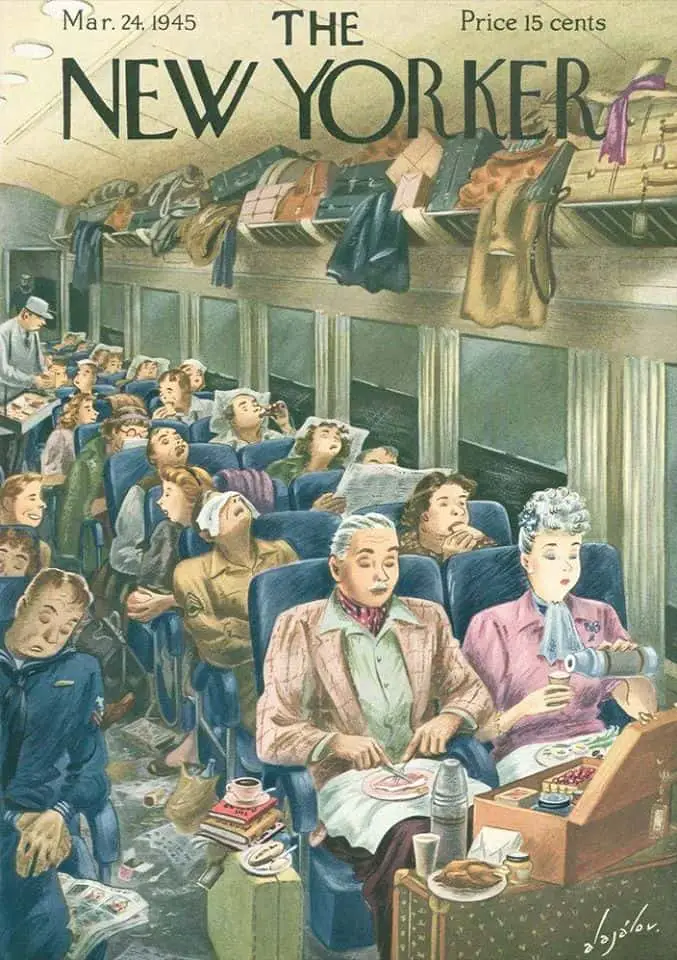

I believe even in illustrations, even in picture book illustrations for children, houses are tidier than in real life. Strewn items are representative rather than photographic. The New Yorker cover below goes in the opposite direction, by creating a shared space which is slightly more haphazard and ‘lived in’ than your average train.

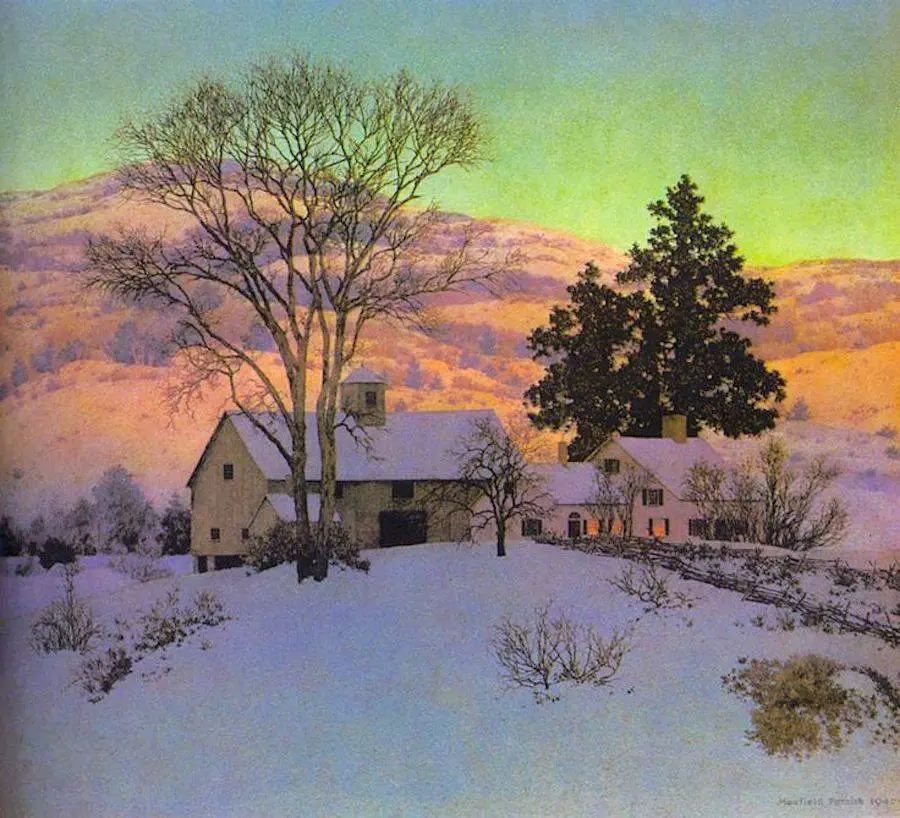

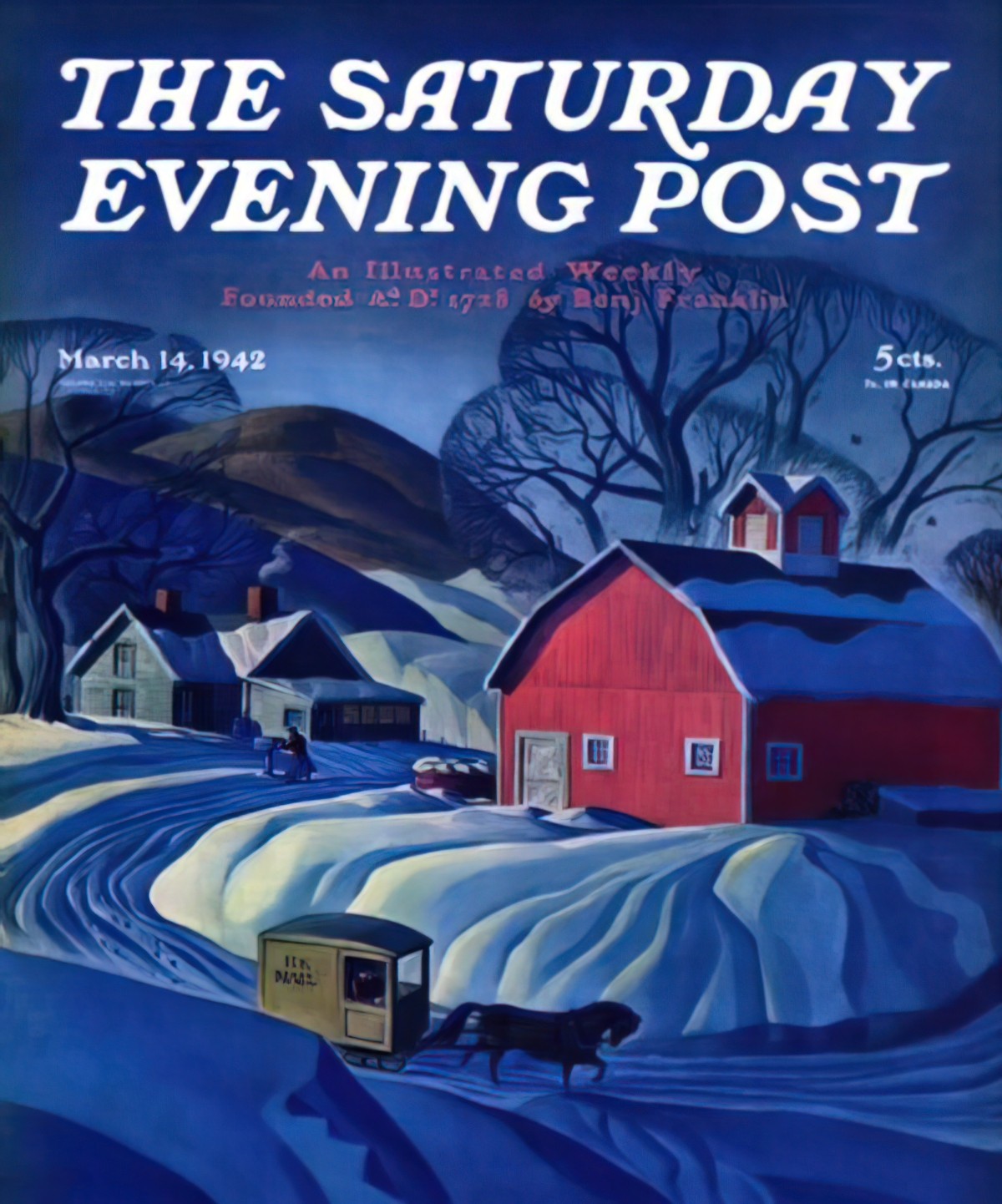

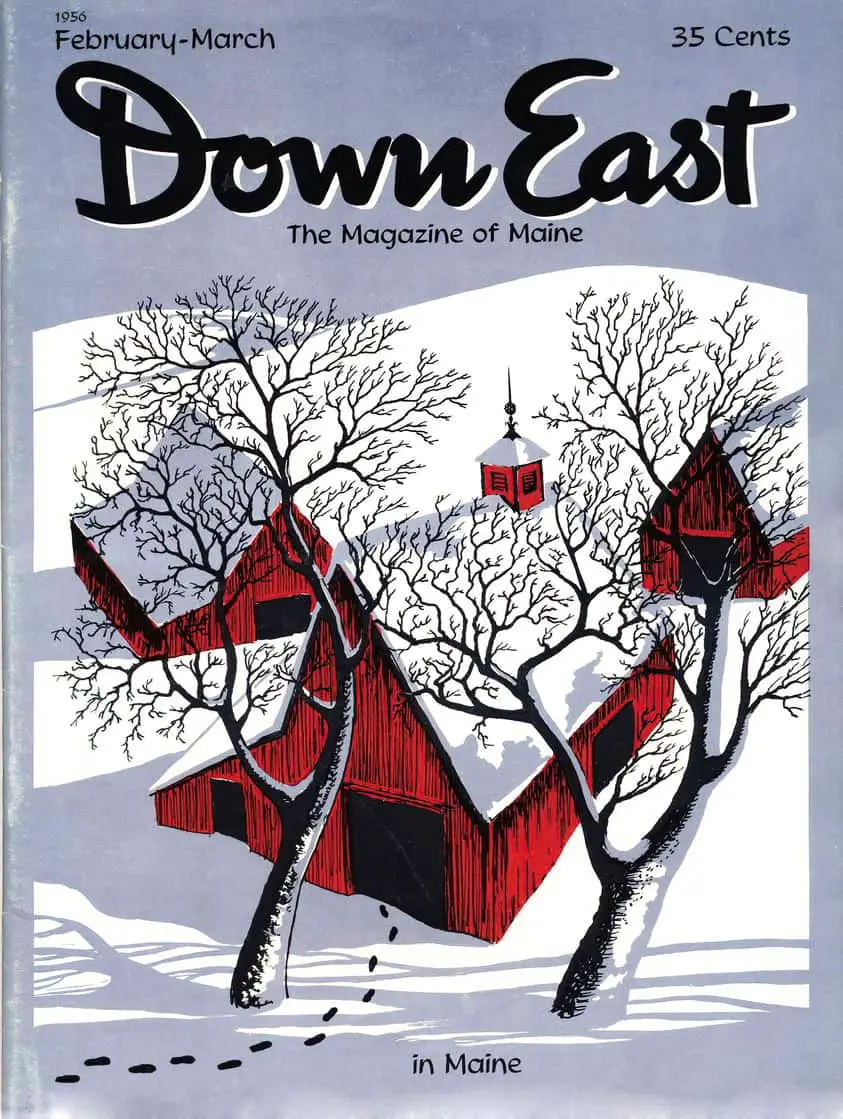

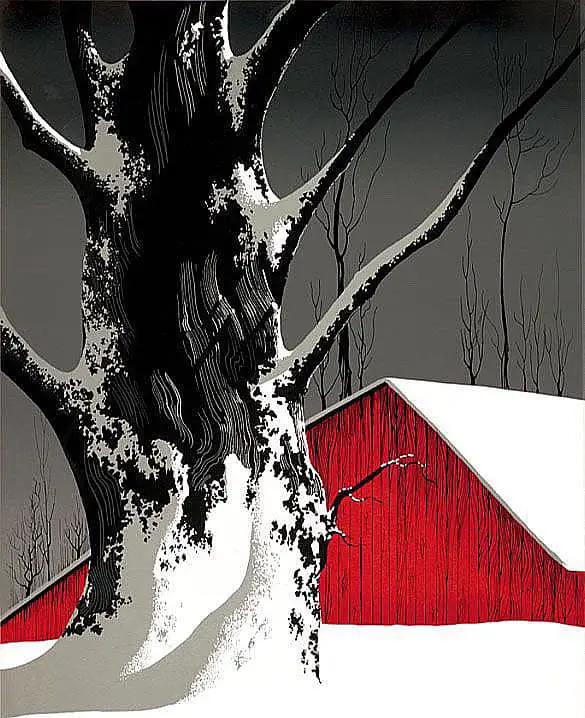

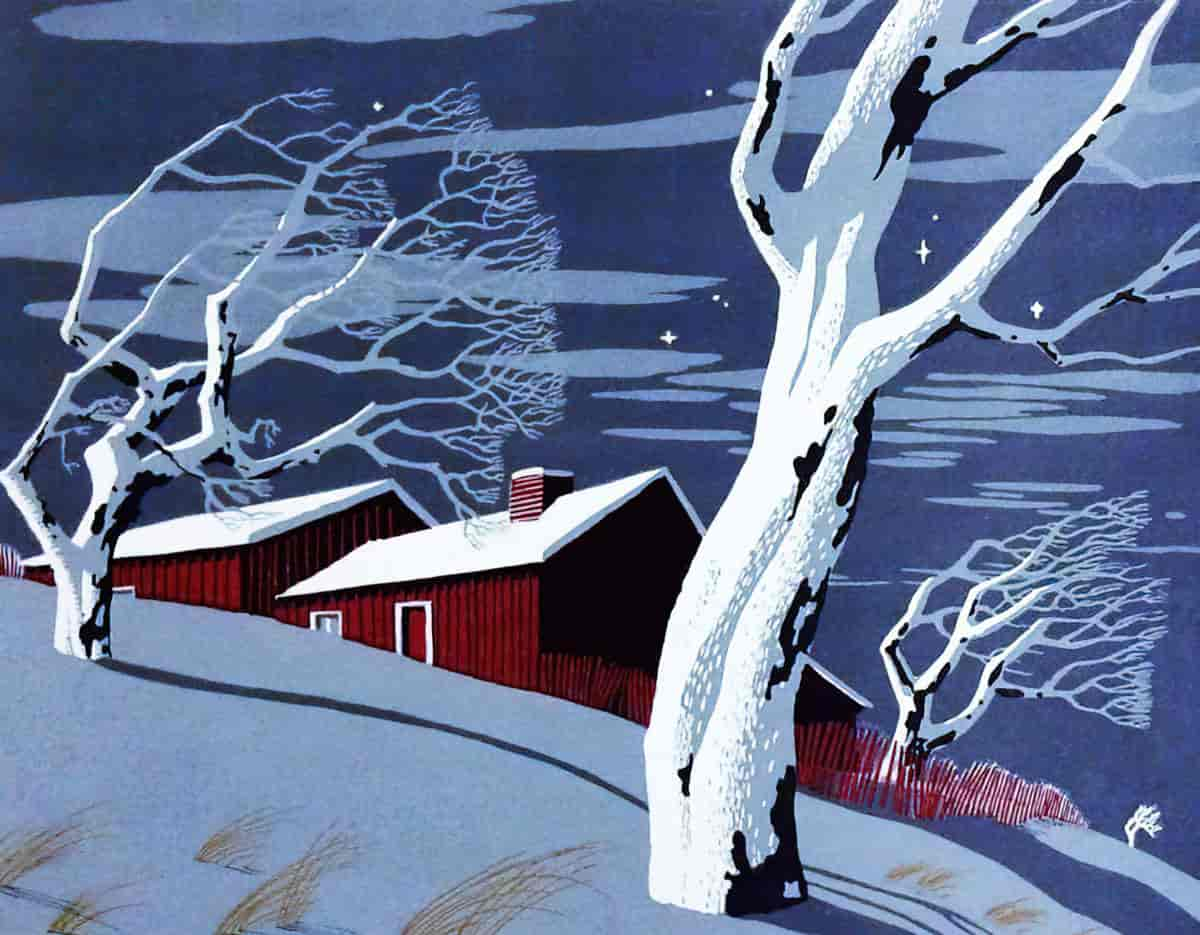

The Cosy-Snowy Juxtaposition

Isn’t it true that a pleasant house makes winter more poetic, and doesn’t winter add to the poetry of a house? The white cottage sat at the end of a little valley, shut in by rather high mountains; and it seemed to be swathed in shrubs.

Baudelaire, French poet

This cosiness is exploited in full in the horror genre for all ages. Take Misery, in which Stephen King goes out of his way to create a cosy, loving shelter after a brutal car accident, before inverting the cosiness to invoke terror.

In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard makes some related points:

- The reason we feel warm is precisely because it’s cold outside.

- Dreamers tend to love winter. More time to dream.

- Edgar Allan Poe had a thing about big, heavy curtains. When the curtains are dark, the snow outside seems even whiter. It’s all about juxtaposition and contrast.

- ‘Everything comes alive when contradictions accumulate’.

- When snow covers everything outside, the world is pretty much obliterated. There is no longer any struggle between the house and the environment. The whole universe has a single, unifying colour. ‘The winter cosmos is a simplified cosmos.’

- ‘Winter is by far the oldest of the seasons. … On snowy days, the house too is old.’

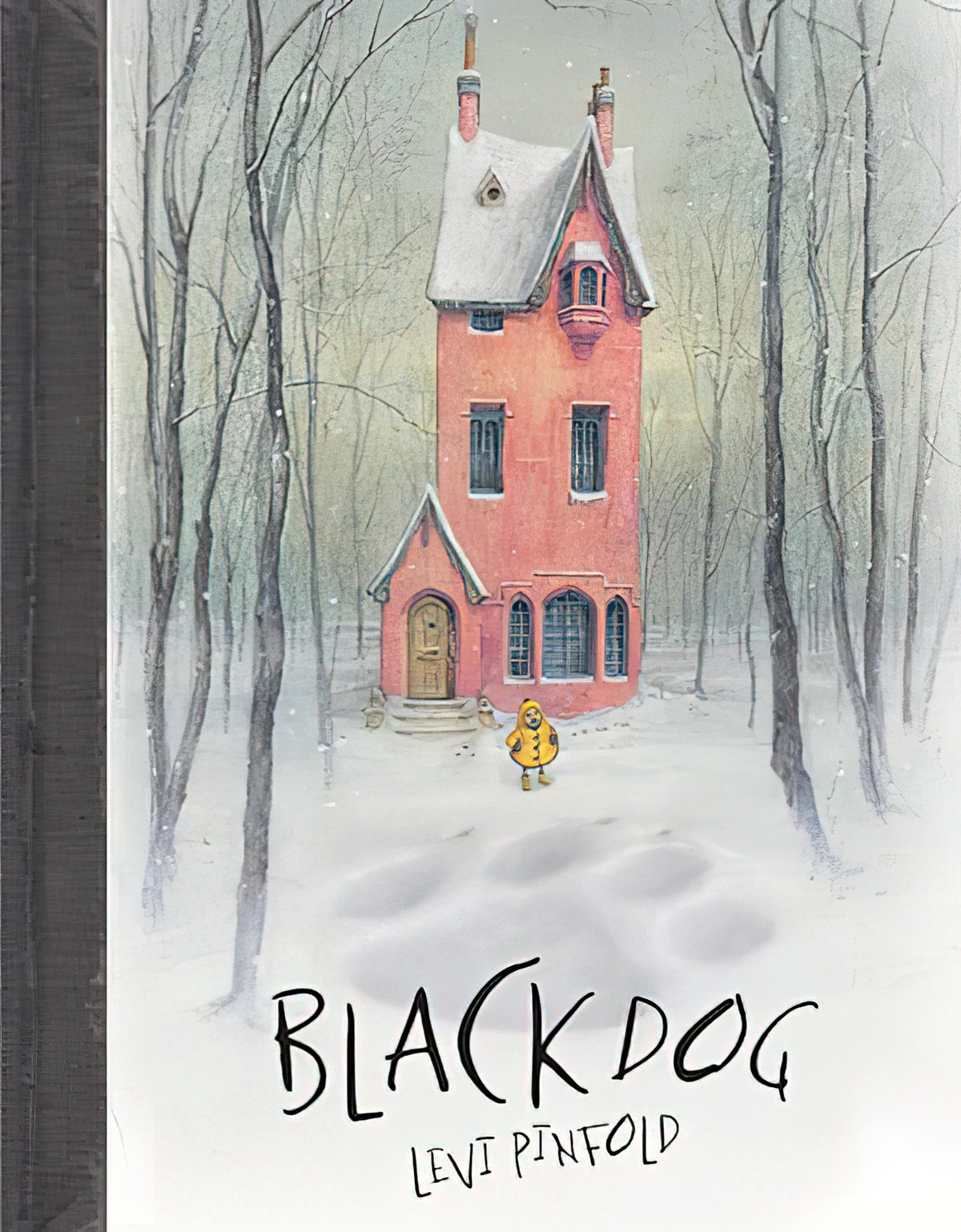

In Blackdog we also have a cosy house (on the inside) but it is snowing outside. In this house, ‘everything may be differentiated and multiplied’ (Bachelard).

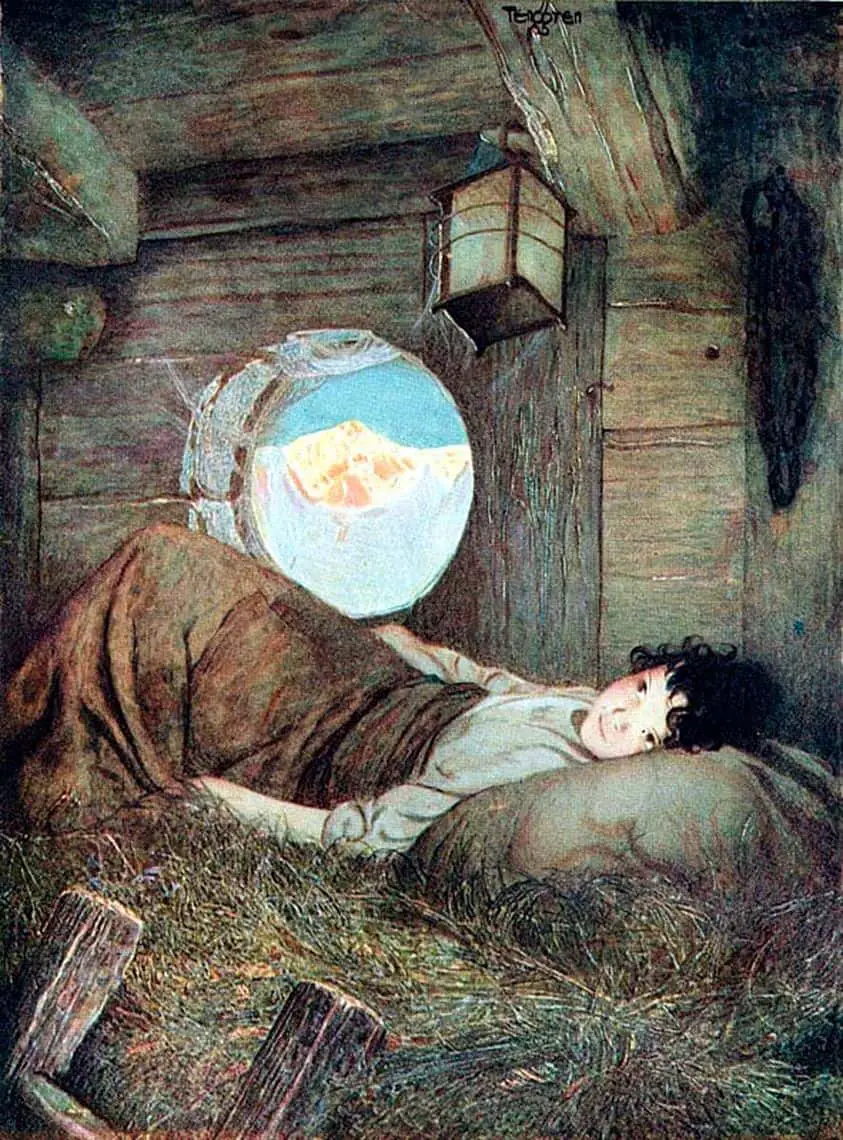

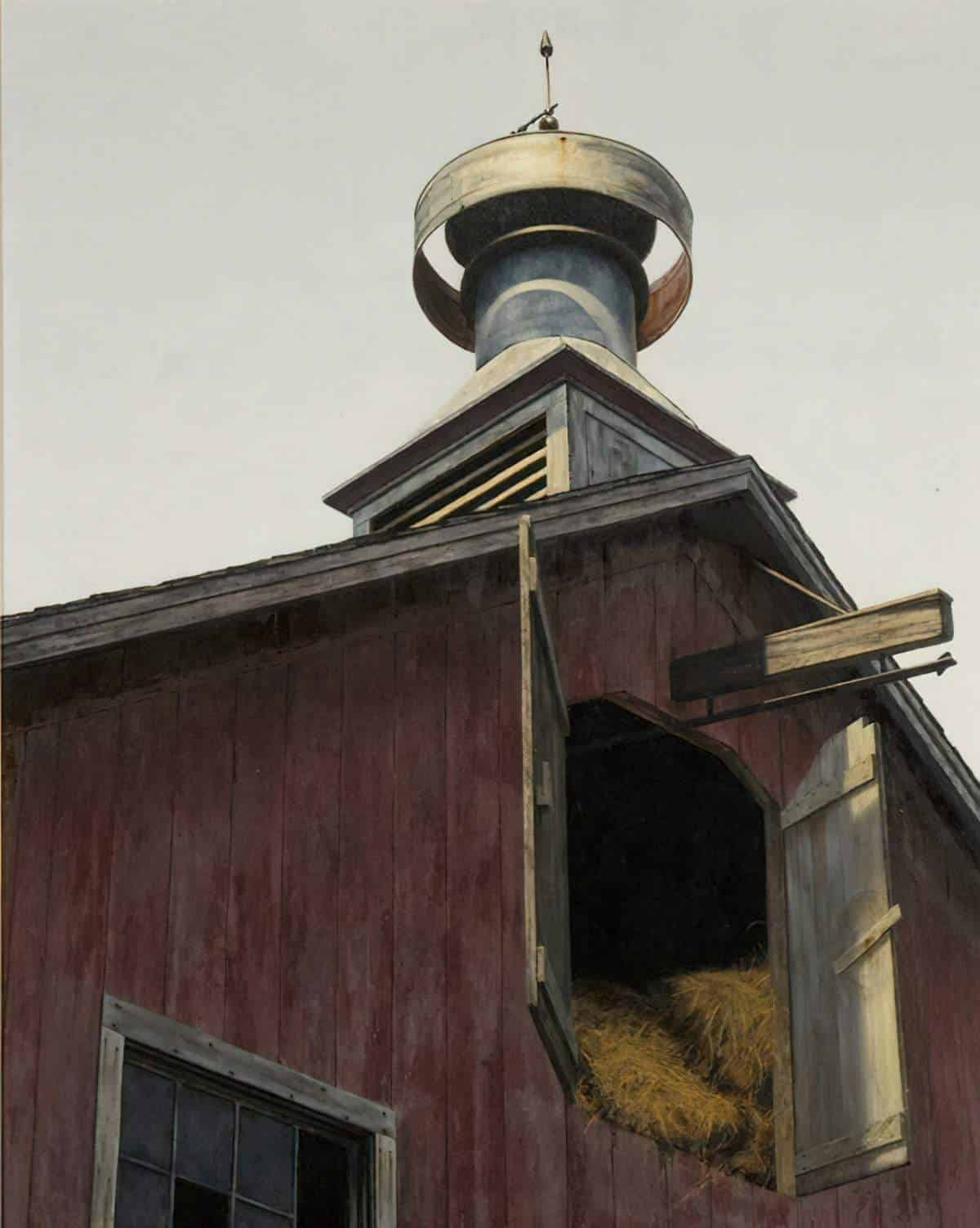

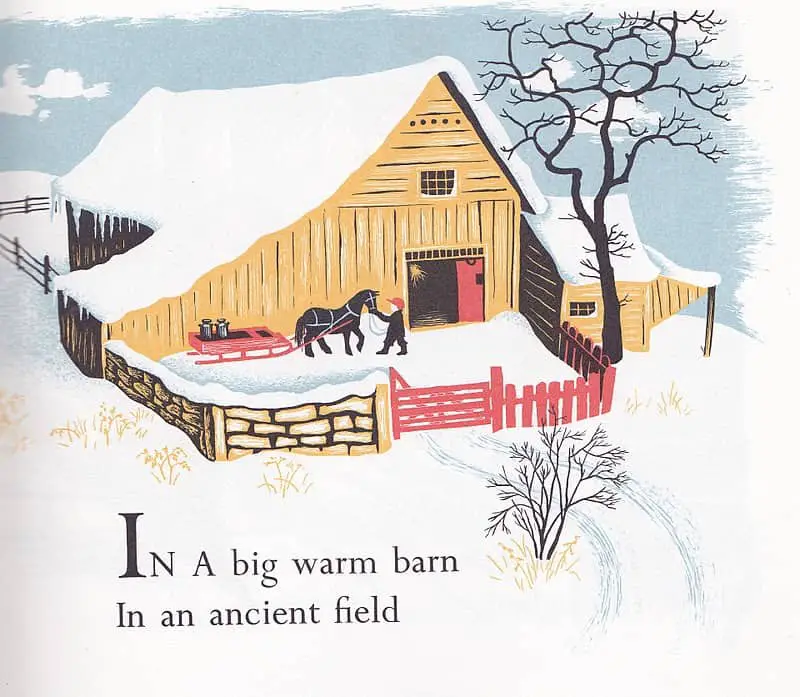

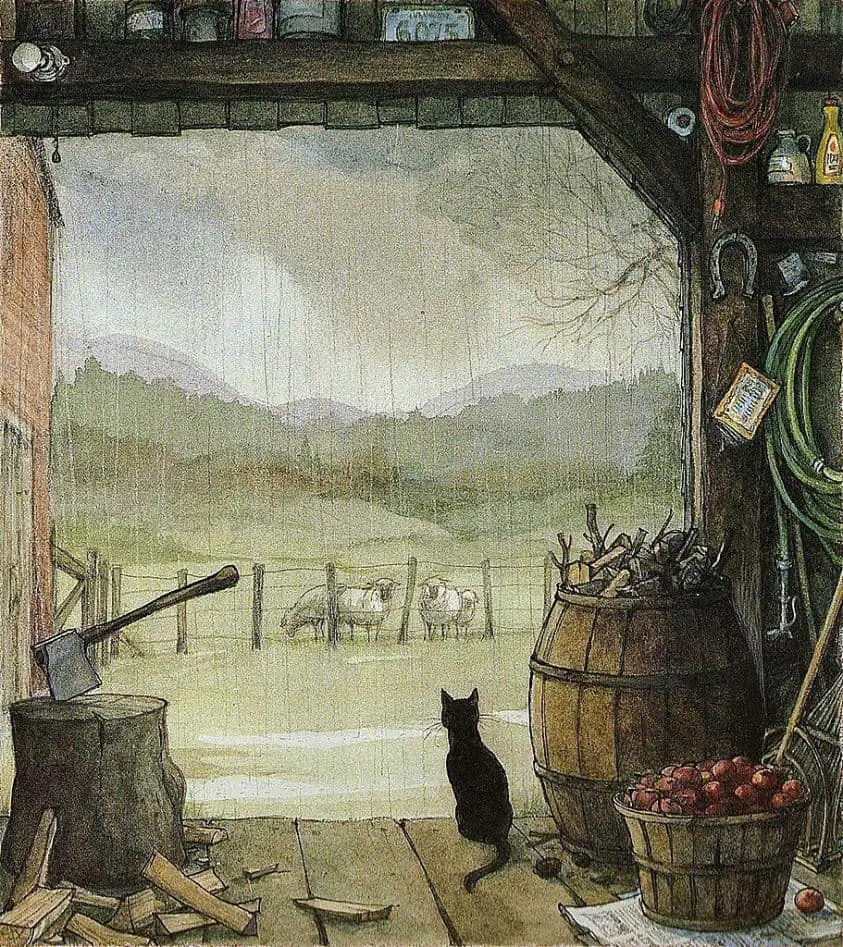

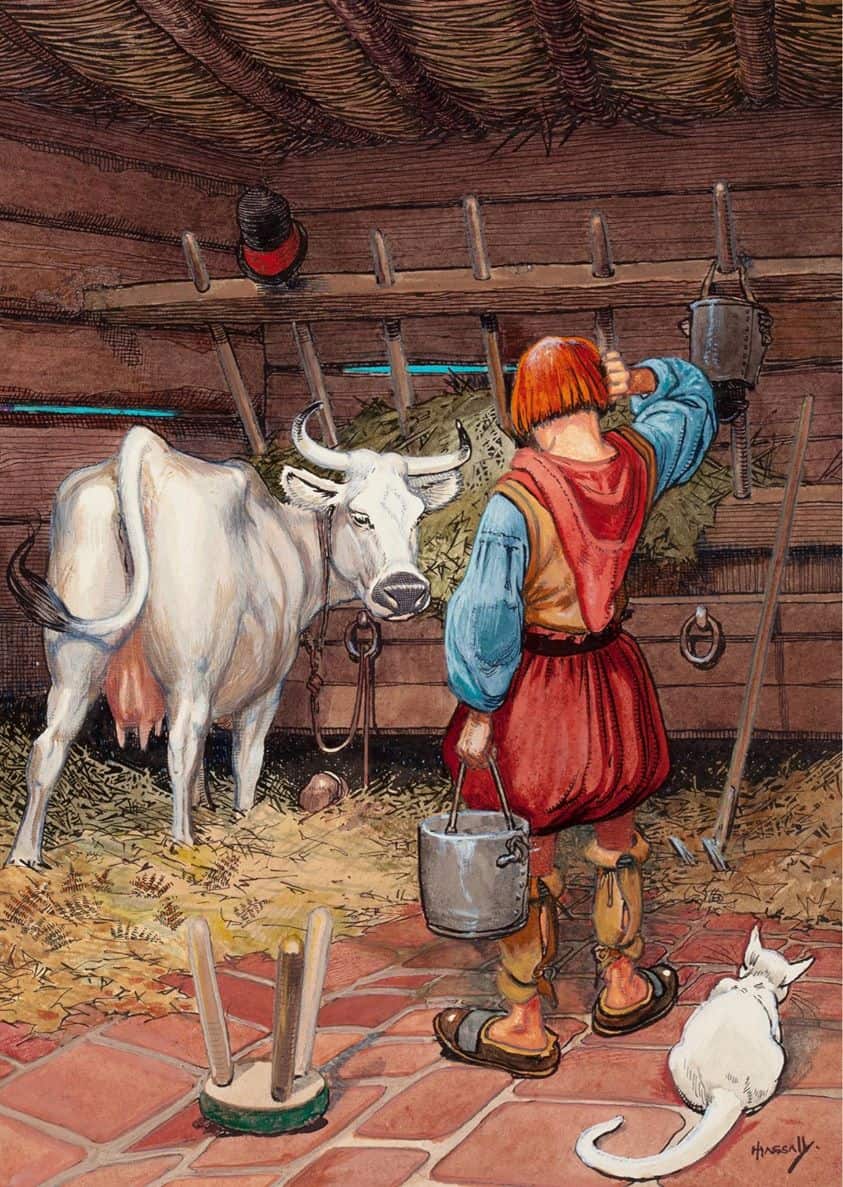

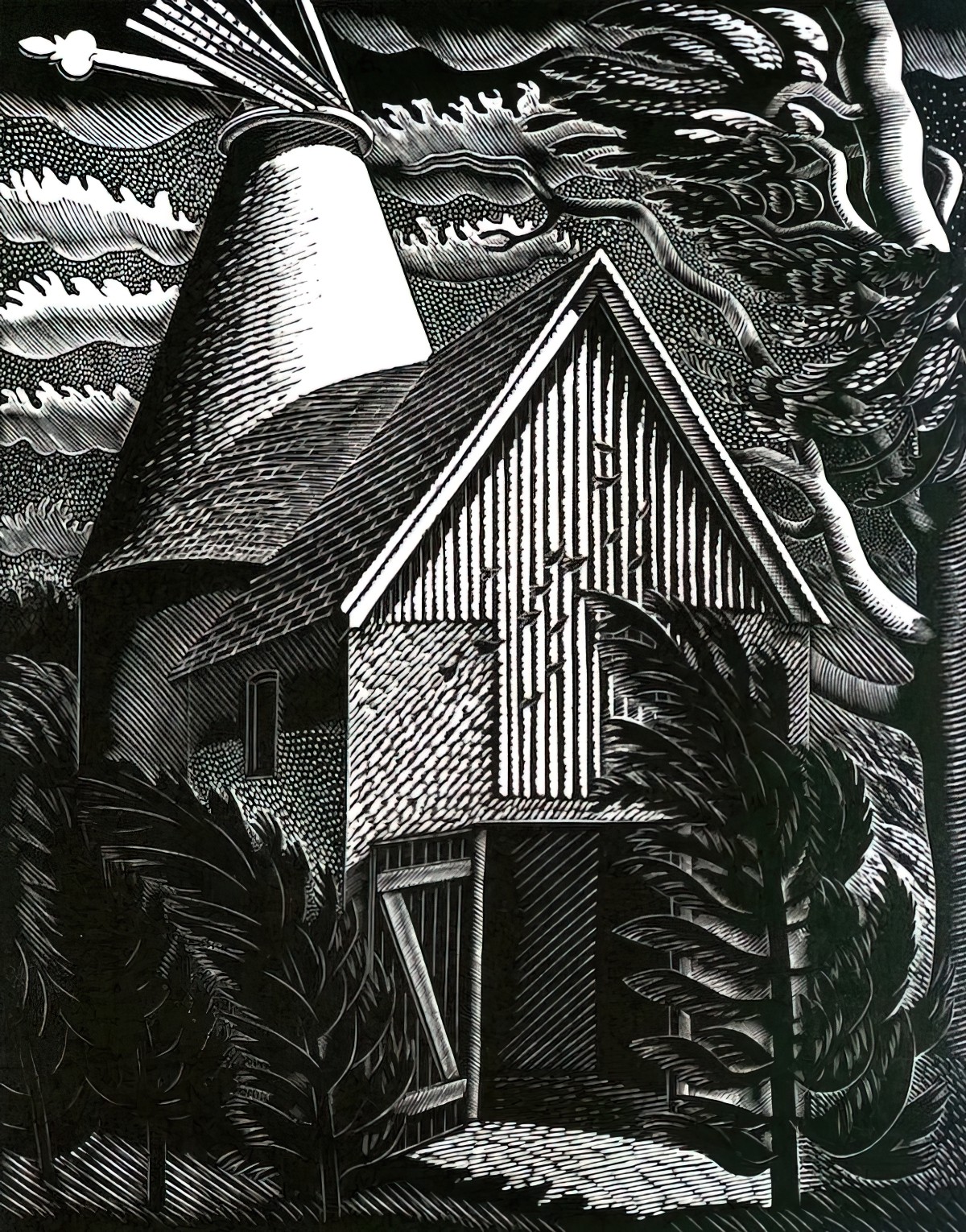

The Barn As Warm Cosy House

In pastoral children’s literature especially, the barn is sufficiently removed from the house to allow a warm, safe, cosy environment of the child’s own.

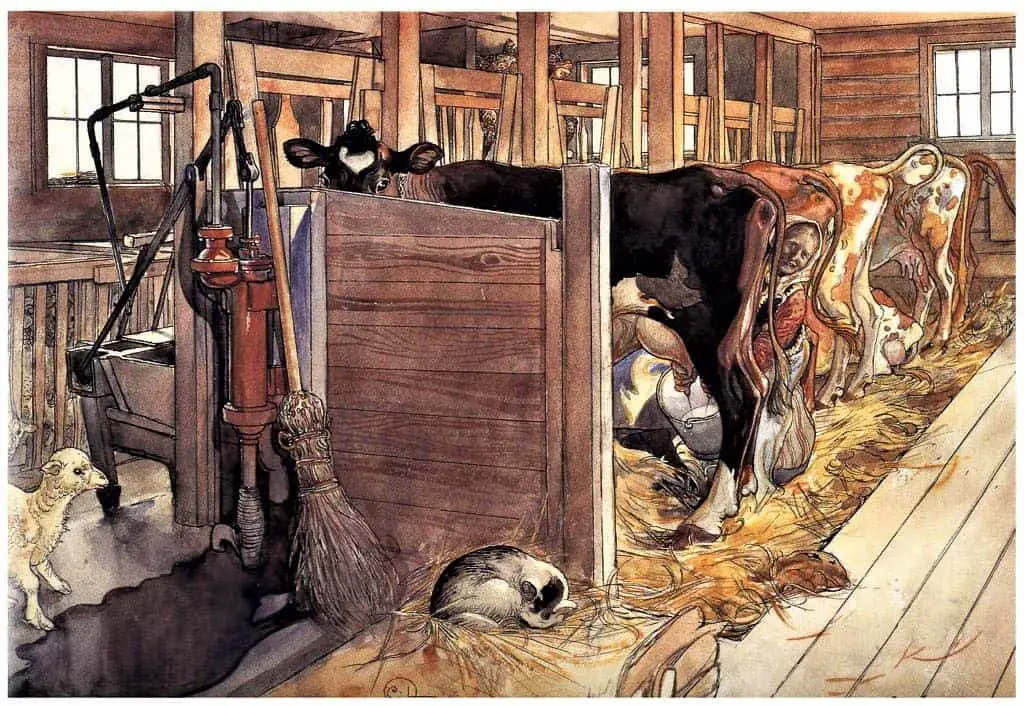

In Charlotte’s Web, E.B. White describes the barn at the beginning of chapter three. When writing notes for the film adaptation of Charlotte’s Web, White apparently included, “When you enter the barn cellar, remove your hat.” He seemed to regard barn cellars as a kind of cathedral. Via reading his correspondence we know he also liked the smell of manure, which reassured him that life is cyclical.

Indeed, the richness of White’s barn epitomizes the medieval concept of plenitude, the notion that God created the world full and complete. Such a notion is wholly compatible with the pastoral tradition that underlies a great number of children’s books. The presence of death in White’s idealised and bucolic paradise also is in keeping with the literary and artistic tradition of the pastoral

The Annotated Charlotte’s Web by Peter Neumeyer

That said, White was keen to avoid painting a community of barn inhabitants who all got on like the perfect utopian community. The goose is unsympathetic to Wilbur. White himself described the barn animals as “rugged individualists”.

See also: Storybook Farms

FURTHER READING

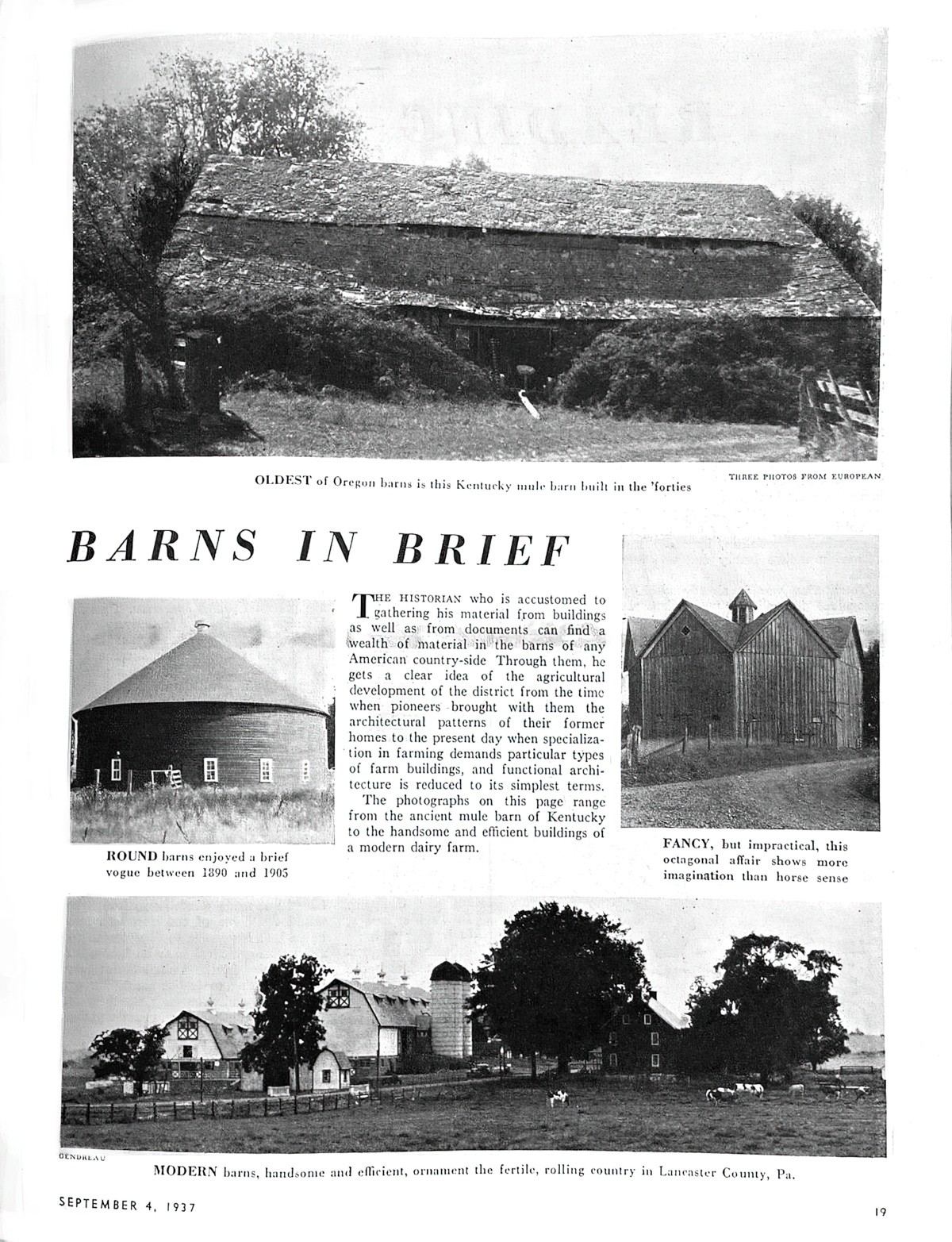

Big House, Little House, Back House, Barn: The Connected Farm Buildings of New England

“Big house, little house, back house, barn”―this rhythmic cadence was sung by nineteenth-century children as they played. It also portrays the four essential components of the farms where many of them lived. The stately and beautiful connected farm buildings made by nineteenth-century New Englanders stand today as a living expression of a rural culture, offering insights into the people who made them and their agricultural way of life. A visual delight as well as an engaging tribute to our nineteenth-century forebears, Thomas C. Hubka’s Big House, Little House, Back House, Barn: The Connected Farm Buildings of New England (UP of New England, 2004) has become one of the standard works on regional farmsteads in America.

INTERVIEW AT NEW BOOKS NETWORK

Header image: Maxfield Parrish- Winter Wonderland