A while back I read short story “The Tyger” by Stephen King and got to thinking about the especial horror of bathrooms and plumbing. Sure enough, someone has given names to very specific fears:

Aquamechanophobia is the fear of machines having to do with water, submerged or not. Pool drains also fall under this category. These fears include pool drains, pool lights, pool pumps, pipes with water running through, toilets, sinks bathrooms, etc.

Submechanophobia is the fear of man-made objects that are submerged under water. People experiencing this condition are typically afraid of things like buoys, submarines, sunken ships, and many other objects that sink into the ocean.

Ray Bradbury has taken the ancient symbolism of the water well and transferred it to a contemporary (mid 20th century) setting, and added some gothic elements.

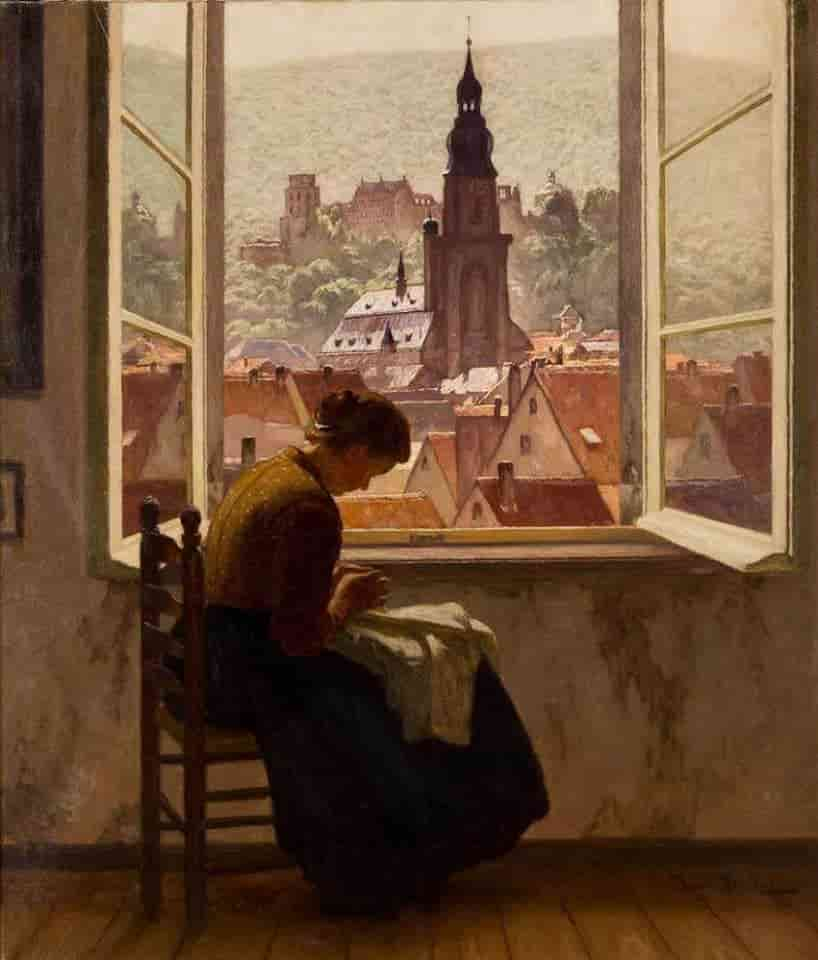

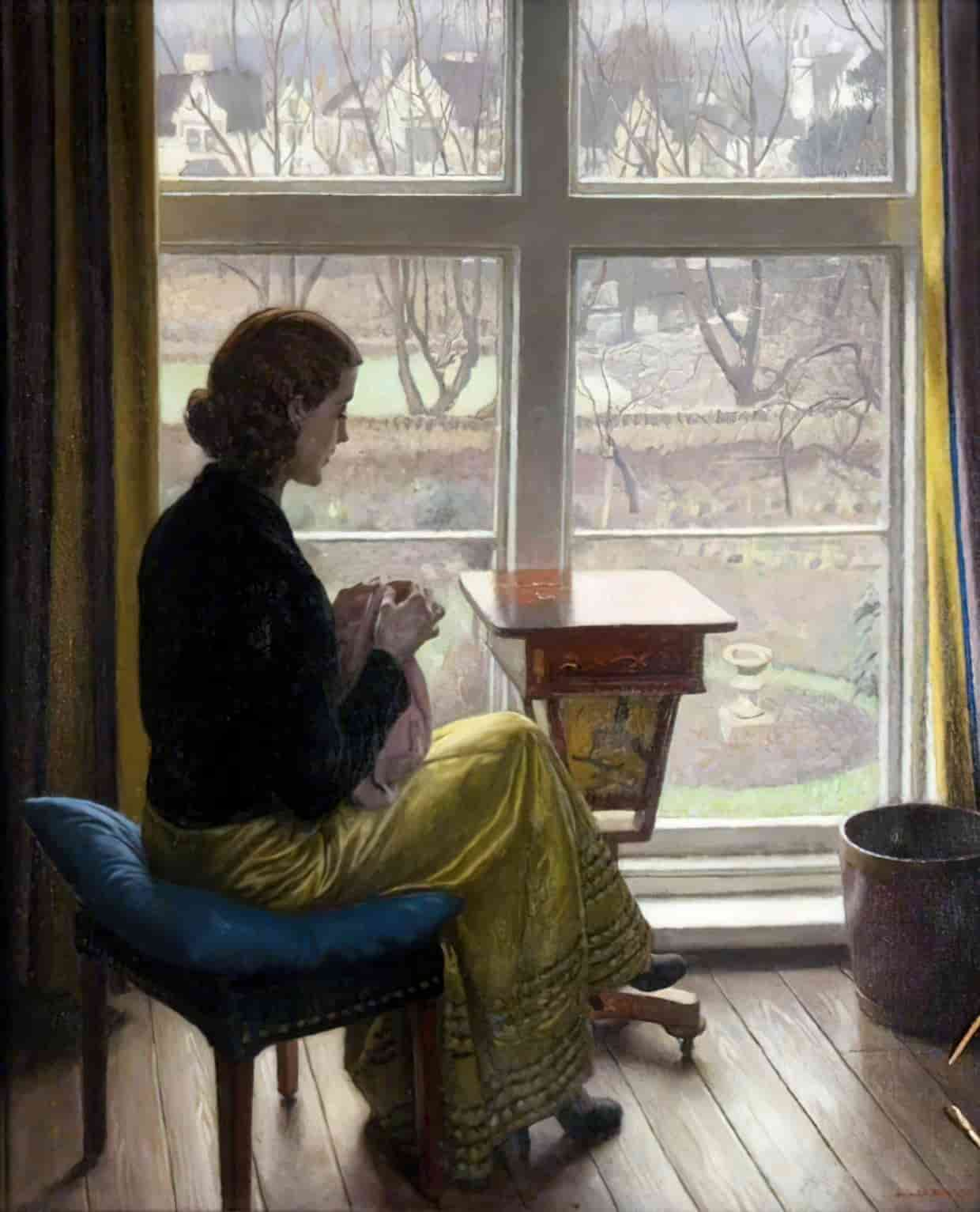

But Ray Bradbury’s short story “The Cistern” can, by contrast, be read as a celebration of plumbing and groundwater solutions, normally invisible to those of us who live in towns. He has chosen for this celebration two women sitting near a window while sewing — the subject of many examples of fine art over the last few centuries.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE CISTERN”

- Two sisters (Juliet and Anna) sit inside a lamp-lit living room embroidering tablecloths. It’s raining outside. So far, so ghost story. (There’s a long history of stories told by women, for women, to enliven the mundane work performed by women. We call the masculine equivalent tall tales; women have created oral fairy tales and ghost stories.)

- Ray Bradbury is careful to portray the two sisters as middle-aged and dull in appearance. Perhaps the subtext is this: These two women have nothing going on in their own lives, which is why the more imaginative and playful of the pair makes up a (self-insert) story about two lovers?

- Anna is clearly bored by the embroidery. Her head is pressed against the window in a childlike way (though it soon becomes clear these two women are middle-aged). Windows carry symbolism in their own right, though the symbolism of windows tends to be overlooked. From the outside, a passer-by would probably see droplets of rain reflecting off the window, as aforementioned lamp-light reflects off the rainy street. (This is significant.)

- Anna’s thinking about something we pass everyday with nary a thought to their purpose: the manhole covers of cisterns.

Cistern has two related meanings. There’s the cistern on your home toilet (assuming yours flushes). That’s the little tank which holds the water for the next flush. Then you’ve got your huge, underground cisterns which hold water for an entire town. These are reservoirs, collecting rainwater.

- To Anna, the entrance to the cistern functions imaginatively as a fantasy portal, leading to an underground city mirroring the familiar one, above ground. She tries to engage Juliet in her imaginative game: What would it be like to live in an underground cistern? But Juliet is having none of it. Anna imagines the woman lover as ‘beautifully dead’ — a sure sign she’s been reading Gothic fiction.

- Perhaps because Juliet is initially scathing of her story, Anna adds more detail. There’s a pair of lovers down there. The man died five years ago. The woman more recently. Now Anna has captured Juliet’s interest. And as readers, we wonder if Anna has the gift of clairvoyance. (It is Ray Bradbury, after all.) In any case, now we have a story within a story.

- “She lifted her hand, pointing, as if she herself were done in the cistern, waiting.” This feels like the Beryl Fairchild character archetype (cf. Katherine Mansfield): a spinster hasn’t been chosen by a man for marriage, so she spends her life looking out windows and imagining romance instead.

- Anna compares the tragic lovers to flowers — first a Japanese flower. The woman’s hair fans out like a flower (or like Ophelia by John Everett Millais (1851-2).

- Anna personifies the water, which brings the two drifting bodies together. She reassures her sister, “It’s not wicked this way.” This says something about the characters: As gentle-women they are expected to sit around and observe passively until life comes to collect them. Anything more active, especially as it pertains to finding a lover, would count as ‘wicked’. But if the tide takes you to your lover? Well then, that can’t be helped. It’s fate.

- The hair of the sisters is gray. It is also gray outside. The cistern water is also gray (and brownish, like tobacco). Bradbury is clearly comparing the sisters themselves to their environment, but why? I figure he is invisibilising them. These two are so ignored by society that they may as well be the manhole covers to the cisterns. People walk by every day and no one notices them. Anna feels an affinity for those manhole covers. Feeling invisible (as if she were underground) she is reclaiming the invisibility for herself, turning it into something more exciting, more erotic.

- It is revealed that the man Anna imagines in this story is a lover of long ago called Frank. She has ever since regretted failing to wrest him away from his mother. (We can deduce the rest of that particular story. I somehow doubt the mother was the issue.)

- The more sensible Juliet falls asleep in her chair, but is soon awoken by the sound of the front door opening, wind rushing in. Anna is gone.

- Anna has taken leave of her senses. Or else there’s a supernatural force at play. In any case, she has been called down into the cistern, where (we extrapolate) she hopes to be taken to a watery grave, living out the contents of her own gothic fantasy.