I’m going on an adventure

Athey Thompson

And who knows, what will be

Or, what will become of me

But one thing is for sure

An adventure it shall be

Edgar Rice Burroughs is probably the most influential writer in the entire history of the world. By giving romance and adventure to a whole generation of boys, Burroughs caused them to go out and decide to become special. That’s what we have to do for everyone, give the gift of life with our books. Say to a girl or boy at age ten, Hey, life is fun! Grow tall! I’ve talked to more biochemists and more astronomers and technologists in various fields, who, when they were ten years old, fell in love with John Carter and Tarzan and decided to become something romantic. Burroughs put us on the moon. All the technologists read Burroughs. I was once at Caltech with a whole bunch of scientists and they all admitted it. Two leading astronomers—one from Cornell, the other from Caltech—came out and said, Yeah, that’s why we became astronomers. We wanted to see Mars more closely.

Ray Bradbury, The Paris Review

NINETEENTH-CENTURY ADVENTURE STORIES

Examples of The Adventure Story

The British Adventure Story

- Robinson Crusoe (published in 1719, written by Daniel Defoe, though not written specifically for children, filtered through to the classroom). Gave rise to the term ‘Robinsonnades’.

- Swiss Family Robinson (by J.D. Wyss, introduced into England in 1814)

- Masterman Ready, Settlers in Canada, Children of the New Forest, The Little Savage (written by a Captain Marryat, who didn’t think much of Wyss’s geography or seamanship. His stories were the first to be written specifically for children. He’d had a vivid career at sea. His books are heavily didactic.)

- English Family Robinson (by Mayne Reid)

- Mark’s Reef (by Fenimore Cooper)

- The Coral Island (by R.M. Ballantyne. Ballantyne the brave was born Edinburgh 1825 and spent his 20s working in Canada for the Hudson’s Bay Company. He wrote his first adult book while stationed at one of the loneliest outposts there, while in charge of one Indian and a horse. The mail came twice per year. He published The Young Fur-Traders age 31. He then wrote Ungava and The Coral Island, his best known story, and a lot of other stories besides.)

- Canadian Crusoes (the first Canadian children’s book of any importance, written by Catharine Parr Traill — similar to early Australian children’s stories)

- Ivanhoe and other books by Sir Walter Scott were very popular in their day though have fallen out of fashion. But Scott’s work has been as much of an influence as Defoe’s.

- The works of W.H.G. Kingston, a prolific English writer of boys’ adventure novels.

- Treasure Island (by Robert Louis Stevenson — inspired by Kingston, and Ballantyne the brave. )

- King’s Solomon’s Mines (by Rider Haggard is borderline adult fiction — a triumph of the exotic)

- Conan Doyle, John Buchan, Anthony Hope, H.G. Wells all wrote for adults but were widely enjoyed by boys.

The American Adventure Story

- Harry Castlemon (prolific but untalented)

- Oliver Optic (even more prolific and also untalented)

- Mark Twain (Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn were the first good, true American adventure stories — like Stevenson when writing Treasure Island, Twain didn’t have the slightest interest in reinforcing conventional morality. Twain denied morality but his stories have a lot of moral irony.)

- Horatio Alger wrote books around the time of the civil war about individuals starting off poor then becoming rich. (Ragged Dick etc.) The “Horatio Alger myth” is the “classic” American success story and character arc, the trajectory from “rags to riches”. An ‘Alger’ story is now a rags-to-riches American story.

- Thomas L. Janvier wrote The Aztec Tereausre-House. There are strong similarities to King Solomon’s Mines. He then wrote In the Sargasso Sea, which is considered outstanding though neglected by some. His descriptions of setting are magnificent and exotic.

The Australian Adventure Story

Many writers setting their adventure stories in Australia had seem to never have been here, and often got the details wrong.

- William Howitt lived in Australia for a couple years and wrote A Boy’s Adventures in the Wilds of Australia, which has accurate descriptions of landscape and fauna.

- Richard Rowe wrote The Boy in the Bush, a set of episodes introducing subjects such as snakes, drought, an old convict, a gold rush. These have been popular subjects in Australian literature.

- J.H. Hodgetts wrote Tom’s Nugget: a Story of the Australian Goldfields

- Gordon Stables wrote From Squire to Squatter

- W.H.G. Kingston wrote stories set in Australia but got the details badly wrong.

Notes On The Adventure Story from Written For Children by John Rowe Townsend

The Victorian English speaking world was very much a man’s world. Men dreamt of building a nation or empire, winning wars. (At least those who were the reading classes.)

Meanwhile, feminine virtues were: piety, domesticity, sexual submission, repression.

Books for boys and girls reflected these attitudes. For boys: life of action on land and at sea. For girls: domestic stories

Adventure stories overlapped with historical fiction. No clear division.

Threesomes are popular in the classic adventure story, each providing a three-cornered contrast to each other. This ensemble remains popular in children’s stories: Harry Potter/Ron Weasley/Hermione Granger; the threesome of Monster House and so on. These days it’s often two boys plus a girl.

In the Crusoe tradition, there’s a lot of detail about how the main characters manage to stay alive (what they eat and where they sleep etc.)

There’s quite a bit of writing about Christian missionaries, and the civilizing effect they have on the local savages.

Treasure Island is one of the best written of these stories, and is still good because of its fast pacing (a modern pacing).

Long John Silver was a new kind of villain: a villain with something heroic about him. This blurred the black and white good and evil that had been an unwritten rule of children’s literature.

American adventure stories have dated even slightly worse than the British ones. Heroes were morally uplifting, unrealistically brave and priggish.

These American books tended to reflect a conventional idea of adventure rather than the real thing. Adventure for the Americans was not the same as for the British. To the Victorian British, adventure was something you found overseas, and to do with building an empire.

But the great American adventure story was about building America. However, despite the expanding of the Western frontier, there were no excellent adventure children’s books about this published at the time. See more about Westerns, anti-Westerns and neo-Westerns.

Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn changed that.

In the second half of the 19th C there came a new kind of adventure story: individuals making their own way in life, making good.

In these books, the poorest of the poor made their way to the top, becoming rich through hard work. A Cinderella story for boys.

Like the historical novel, the ‘good gripping yarn’ of high adventure has had a hard time in the post WW2 years. The wide, wide world has shrunk, so trips to the other side of the world are commonplace. The adventure story has suffered more than any other fictional genre from the competition of films and television. (Adventure is visual, and very well suited to the screen.) The downsides of the screen is that the hero is clearly not you — but the main drawcard of the traditional adventure novel was that a young reader could imagine himself (because the protagonists were always boys) as the hero.

There wasn’t much in the way of wartime adventure stories right after the wars. The wars offered plenty of real-life adventure of the unwelcome kind. But as the years passed, views on what children could and couldn’t read became less restrictive. Writers now write in an unflinching manner about all sorts of horrible things.

FURTHER READING

Transforming Girls: The Work of Nineteenth-Century Adolescence

Transforming Girls: The Work of Nineteenth-Century Adolescence (UP of Mississippi, 2021) explores the paradox of the nineteenth-century girls’ book. On the one hand, early novels for adolescent girls rely on gender binaries and suggest that girls must accommodate and support a patriarchal framework to be happy. On the other, they provide access to imagined worlds in which teens are at the center. The early girls’ book frames female adolescence as an opportunity for productive investment in the self. This is a space where mentors who trust themselves, the education they provide, and the girl’s essentially good nature neutralize the girl’s own anxieties about maturity.

These mid-nineteenth-century novels focus on female adolescence as a social category in unexpected ways. They draw not on a twentieth-century model of the alienated adolescent, but on a model of collaborative growth. The purpose of these novels is to approach adolescence—a category that continues to engage and perplex us—from another perspective, one in which fluid identity and the deliberate construction of a self are celebrated. They provide alternatives to cultural beliefs about what it was like to be a white, middle-class girl in the nineteenth century and challenge the assumption that the evolution of the girls’ book is always a movement towards less sexist, less restrictive images of girls.

Drawing on forgotten bestsellers in the United States and Germany (where this genre is referred to as Backfischliteratur), Transforming Girls offers insightful readings that call scholars to re-examine the history of the girls’ book. It also outlines an alternate model for imagining adolescence and supporting adolescent girls. The awkward adolescent girl—so popular in mid-nineteenth-century fiction for girls—remains a valuable resource for understanding contemporary girls and stories about them.

New Books Network

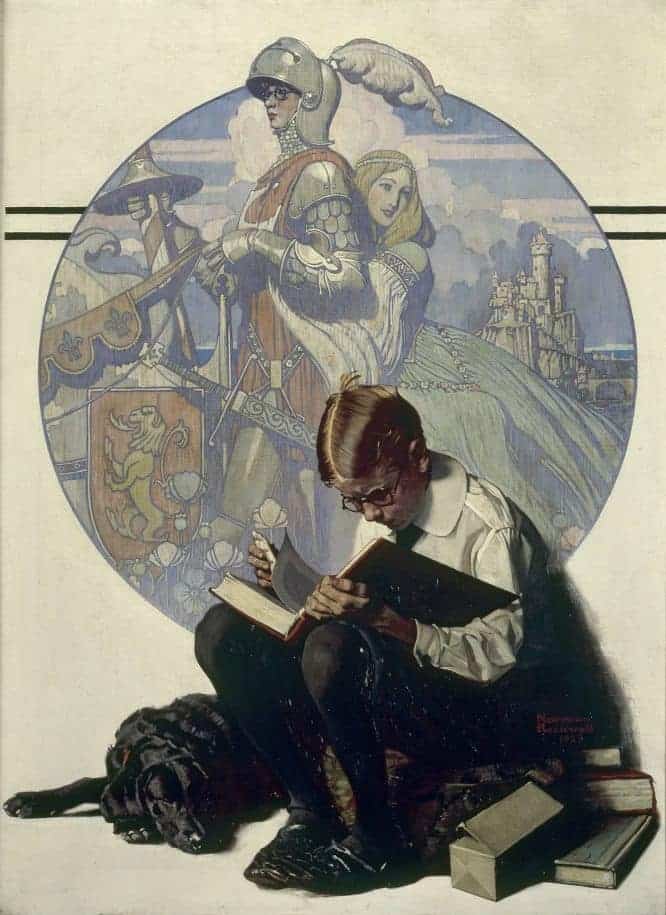

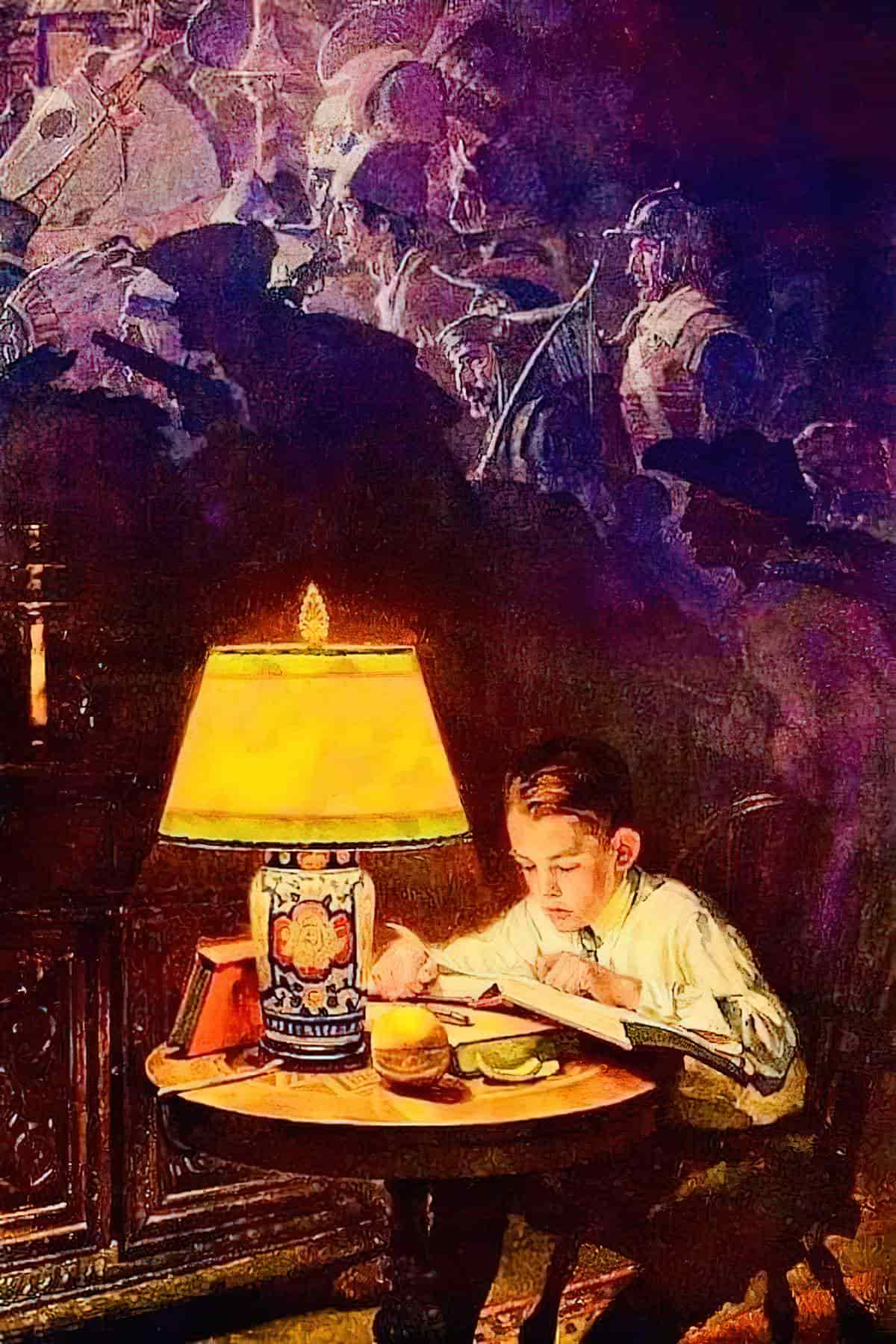

Header illustration: Boy Reading Adventure Story, 1923, Norman Rockwell; 1894-1978