In the 1970s and 80s, Ōtautahi Christchurch was home to a small publishing company called Capper Press. They reprinted significant cultural New Zealand works, and The Castaways of Disappointment Island was one of them. My pop, himself a Southlander born in the 1920s, had grown up with this story, and was very pleased to get his hands on it again. After enjoying it once more as an elderly man, he gave his copy to me. At the age of 12, I devoured it. This is a story enjoyed by adults and kids alike, across time.

I’ve more recently lent my rare hardback copy to others. My father-in-law here in Australia enjoyed the story immensely while recovering from surgery. According to my mother-in-law, Bill rarely read books, but he loved this one. Likewise, my own kid is a somewhat reluctant reader but has requested I read The Castaways of Disappointment Island to him numerous times.

The full title originally released by Herbert Escott-Inman was The castaways of Disappointment Island: Being an account of their sufferings.

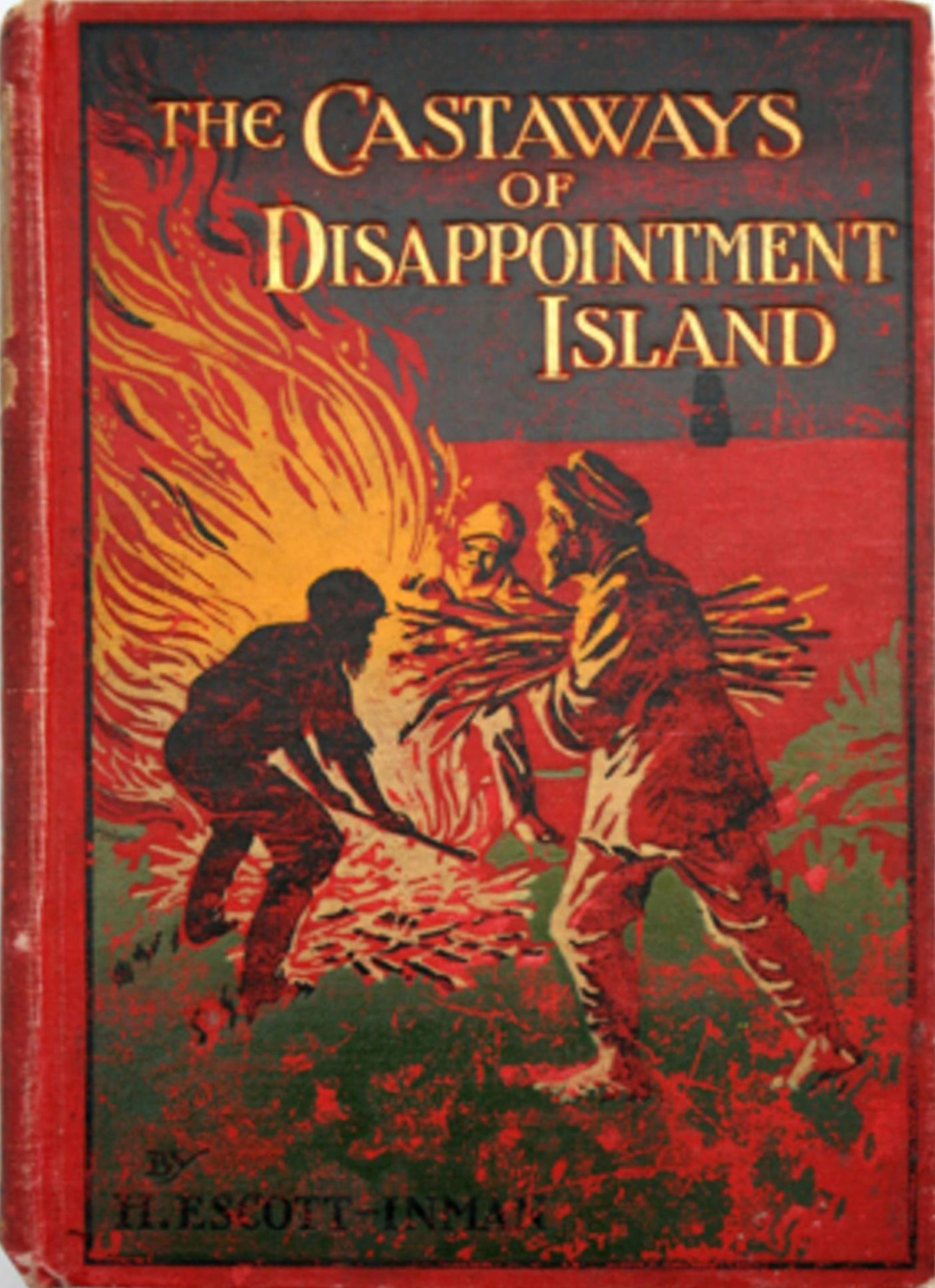

Here is the original hardback cover, published and marketed as an adventure story for boys. (Of course, not just boys were reading them, but girls were expected to read ‘domestic’ stories.)

New Zealand children may have read it if they were primary school students in the 1930s. Briefly, an abridged version of the story was brought back into print as a school reader by Whitcombe’s Story Books.

I loved the book. I read a chapter every night until it was finished. Although I only read it the one time, certain images stayed with me.

I have since recommended The Castaways of Disappointment Island to numerous friends and family. They have all loved it even more than expected. Survivor Charles Eyre is a great storyteller. After an opening lengthy chapter about how he came to be a sailor, the story becomes a page-turner, as fast-paced and exciting as any story written for a contemporary audience.

You can read it for free yourself, if you would like a true 20th century castaway story as told by a man who lived to tell the tale.

Being out of copyright, I’ve decided to read this adventure story aloud once more, this time releasing it as an audiobook. After all, this is a tale transmitted orally, the sort of narrative told around a campfire.

I spent some of 2024 adapting it for audio book. I hope that this story will find a wider audience, as it should.

You will find it wherever you source your audio books:

I read the story myself, just as I wished it to be read, but I have a female voice. And this is a first person story, written by two men. So I used the latest Eleven Labs technology to change my voice to that of a man. Combining my own voice with AI, I have created a brand new narrator.

I have called him Rex Plaskett, a symbolic name, meaning King of the Damp Meadow. If you’d like to hear how female voices can be changed into male voices these days, check out the preview, found at the links above.

BACKGROUND

When Covid-19 was in its early stages, Disappointment Island—an actual, real island—had a moment on social media. People around the world were fantasising about moving to an uninhabited rock free of contagion. Weirdly, for a bit of rock which attracts very little attention on an ordinary day, Disappointment Island started to garner many five star reviews online, none written by visitors who had actually been there, of course:

“Disappointment Island was exactly as disappointing as I’d hoped! Five out of five stars!”

More seriously, there are reasons why Disappointment Island has not been purchased by some billionaire in search of an apocalyptic refuge.

First of all, it’s now a wildlife sanctuary, home to protected species of birds and invertebrates.

But even if it weren’t closed to human habitation, Disappointment Island is… aptly named. To the casual observer, it’s a scrubby bit of rock which juts out of the sea, just three square kilometres in size. No trees grow there.

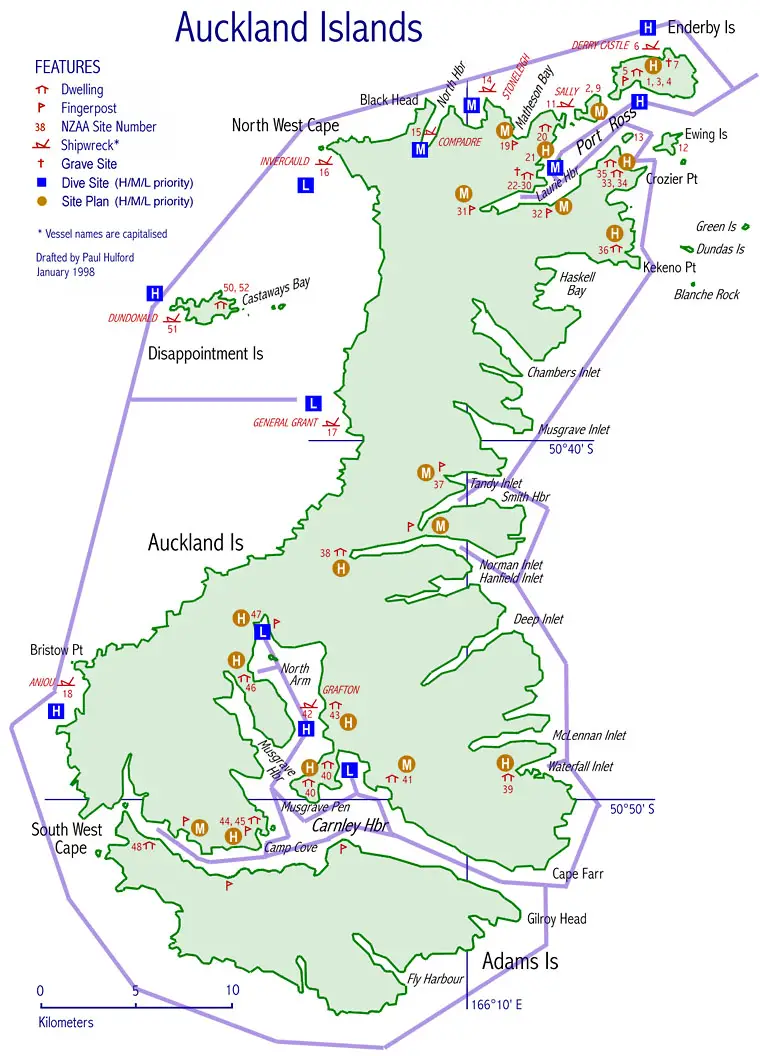

Disappointment Island is just one of an archipelago collectively known as the Auckland Islands [Get onto Google Earth, search for Auckland Islands and you’ll be taken to 50°36’28″S 165°57’17″E.].

Look it up on Google Maps and you’ll be transported to a collection of tiny, subantarctic islands.

By the way, different people mean different things by ‘subantarctic’. Some would say the Auckland Islands are peri-Antarctic, whereas the ‘core’ subantarctic islands comprise Crozet, Kerguelen, Heard and MacDonald, Macquarie, Marion and Prince Edward and South Georgia.

Other peri-Antarctic islands: Amsterdam and Gough Islands, and islands further south of the Aucklands: Bovet (Bouvetøya in Norwegian), Balleny, Scott, Peter I, Shag Rocks, South Sandwich and South Shetland Islands.

Some would classify the Auckland Islands as “oceanic cold temperate”.] islands known as The Auckland Islands, over five hundred kilometres south of the most southern tip of the South Island of Aotearoa New Zealand.

To clarify, Auckland—once again known these days by its Māori name of Tāmaki Makaurau—is the most populated city of Aotearoa New Zealand. You’ll find Auckland near the top of the country. But The Auckland Islands, on the other hand, are right down below. The first white men to discover these islands were aboard the whaling ship Ocean, captained by Bristow, in 1806. White men named them after Lord Auckland of Kent.

After Bristow, the Auckland Islands were visited by American, French and English explorer expeditions, under Wilkes, D’Urville and Ross. Captain Ross thought the main island would serve very well as a penal colony. He even wrote a letter to the Governor of Hobart Town about it. In those days, England was shipping its convicts to Australia and so was Aotearoa New Zealand (a lesser known fact). However, Australia was more than big enough to accommodate the convicts, and also wanted them. Convicts made useful indentured labourers.

But these volcanic “Auckland Islands” were already known as Motu Maha in Māori, meaning “Many Islands”. Māori people also know them as Maungahuka, meaning “Snowy Mountains”, which is how they look from a distance, if not covered in snow, then for much of the year shrouded in a thick, white fog.

Do not confuse The Auckland Islands (which includes Disappointment Island) with the archipelago of coral islands known as The Disappointment Islands, smack bang in the middle of the South Pacific Ocean, and a part of French Polynesia.

Despite all the five star tourism reviews for the subantarctic Disappointment Island, only a few humans have ever set foot on The Auckland Islands, most of them scientists.

Like the hapless sailors of this story, many of these human visitors over the decades never intended their visit—especially white folk. The Māori are known to have great maritime knowledge, and we know the Ngāi Tahu people went there for food and for other natural resources. According to legend, the first Māori to venture this far south were in search of the Aurora Australis. No one has ever settled on this little archipelago for long, though some did try…

Notably, in 1842 about seventy Māori and their Moriori slaves tried living on the Auckland Islands, surviving mainly on seals. They also managed to grow flax. Would would they go there? Matioro, a Ngāti Mutanga ariki (chief/king) did not want to give up his slaves after the Chatham Islands were purchased by The New Zealand Company, a company chartered in the United Kingdom for the purpose of systematic colonisation of Aotearoa New Zealand. Seven years into their new settlement, whalers turned up.

They were now sharing the islands with a small group of drunkard whalers who were eventually disbanded because, as it turns out, no edible vegetables could be grown in acidic peat, the place was wracked by storms and, worst of all for the Whaling Fishery, hardly any whales were caught. It is said that this small group of Māori and Moriori benefited from the existence of those whalers, since they didn’t last long after the whalers had moved on. The whalers lasted two and a half years.

However, I don’t get the feeling it was a fun old time for any of them. The whalers’ surgeon got drunk, fell into the sea, rescued and imprisoned. Next, the jail house burned down.

I cannot even imagine what it was like for the few women. Matioro’s wife attempted suicide. Two infants born there died.

The whalers up and left, though there’s a whole drama around that as well.

The Māori-Moriori tribe split into two factions. Some returned to the Chatham Islands, while another faction decided to settle on Rakiura, also known as Stewart Island—the triangular island under the South Island of Aotearoa New Zealand, close enough to be visible from the mainland. Their descendants remain there to this day.

As this survival story will show, the weather conditions around this little archipelago are rough, to say the least. In the golden age of shipwrecks, a sizeable number of sailors found themselves marooned on one of the Auckland Islands. Only the fittest and more fortunate survived.

OTHER SHIPWRECKS AROUND THE AUCKLAND ISLANDS

All told, between 1833 and 1908, eleven ships were wrecked in the New Zealand subantarctic.

This is why New Zealand’s Southland provincial government decided in 1865 to equip the the main Auckland islands with supply depots. In 1877 the central New Zealand government took over responsibility. This scheme ended in 1927 because sailing ships were no longer taking The Great Circle (Clipper) route.

These supplies were to keep any stranded sailors alive until eventual rescue, which was always by government steamer. Vegetables were planted. Ill-advisedly, farm animals and rabbits were released for food purposes. The fragile ecosystem was forever changed.

Unfortunately for the castaways of this story, who ended on Disappointment Island, these relief depots were set up on the Auckland, Campbell, Antipodes and Bounty Islands, but not on this small one. Disappointment Island is not far—but also very far—from the main Auckland Island, depending on whether you have to swim to it, or whether you’re looking at it on a map from the comfort of your office chair.

The Castaways of Disappointment Island is not the only, nor the first, book published about being marooned as a castaway on The Auckland Islands. For 20 months between 1864-1865, five crew from the Grafton shipwreck managed to survive in similar fashion. If you enjoy this story, I recommend checking out Wrecked on a Reef by French sailor François Edouard Raynal, first published 1869. There is a 2003 English edition with additional appendices by scholar Christiane Mortelier, who believes this account was a heavy influence on Jules Verne, and his famous classic novel The Mysterious Island.

That all went down before Charles Eyre was born.

Who was Charles Eyre?

THE AUTHOR AND THE STORYTELLER

After seven bleak months on Disappointment Island, a number of the Dundonald castaways of this story did make it back to civilisation. One of the survivors knew he had a ripping yarn to tell, and this fellow—Charles Eyre—spoke to a well-known English children’s author by the name of H. Escott Inman. Reverend Inman wrote adventure stories. The Castaways of Disappointment Island was published in 1911 by S. W. Partridge & Co. Ltd., four years after rescue, and marketed specifically at boys. However, adventure stories have always been popular with all genders. These days, of course, the shipping industry is more diverse.

Charles Eyre had grown up in London.

In 1907, Charles was a young man travelling the world as an apprentice mariner. Even before his disastrous time on the Dundonald, he’d had his share of traumatic sea adventures. I do wonder if he told his story to children’s author Reverend Inman partly as a form of therapy.

THE DUNDONALD

The Dundonald was a type of ship known as a barque. Think four masts, many sails. This ship was carrying 30,000 bags of wheat, a somewhat time-critical cargo which benefits from fast delivery.

It weighed 2205 tons.

The 28-man crew had set out from Sydney, intending to reach Falmouth in Cornwall, taking the clipper route, which is more dangerous than going via the Indian Ocean, but is significantly quicker, as it makes use of The Roaring Forties—the very windy strip of ocean at the forties latitude. Taking the clipper route also required rounding Cape Horn, where two ocean currents converge. It’s a dangerous route, but mariners had been prioritising speed over safety since the gold rush in the mid 1800s. Many European settlers to the Antipodes also took this route—sure, it was more dangerous, but living on a ship for months on end is also medically dangerous, even with the best-case scenario of seas and weather.

To say the mariners on the Dundonald didn’t make it all the way back to Europe is an understatement. After leaving Sydney, these mariners had nothing but bad luck with the weather. During a localised storm—known as a squall—the Dundonald hit rocks and sank.

Unfortunately for the mariners of the Dundonald, eleven men drowned in the sinking.

Another seventeen men found themselves swept onto Disappointment Island, which is about as far from Cornwall as it’s possible to get.

50°36’28″S 165°57’17″E

DISAPPOINTMENT ISLAND

Remember those supply huts I was talking about? The ones provided by the New Zealand government for incidents such as these? Well, those were on the main island. But these fellows had washed up onto a tiny, adjacent island without supply huts. There’s seven kilometres of water between that kitted-out main island and the bit of rock known as Disappointment. That may not seem far, but these were very cold, open waters. At the beginning of the 1900s, swimming was not a common activity for Europeans. It’s unlikely these men ever had the chance to learn. Even sailors did not expect to find themselves in the drink, and if they ever did, swimming skills aren’t much help when you’re in the middle of an ocean. Even in this case, with an island visible in the middle distance, the strongest of human swimmers would be susceptible to pulmonary edema, a life-threatening condition. The body slows down, they had no wetsuits, they didn’t have much fat on them.

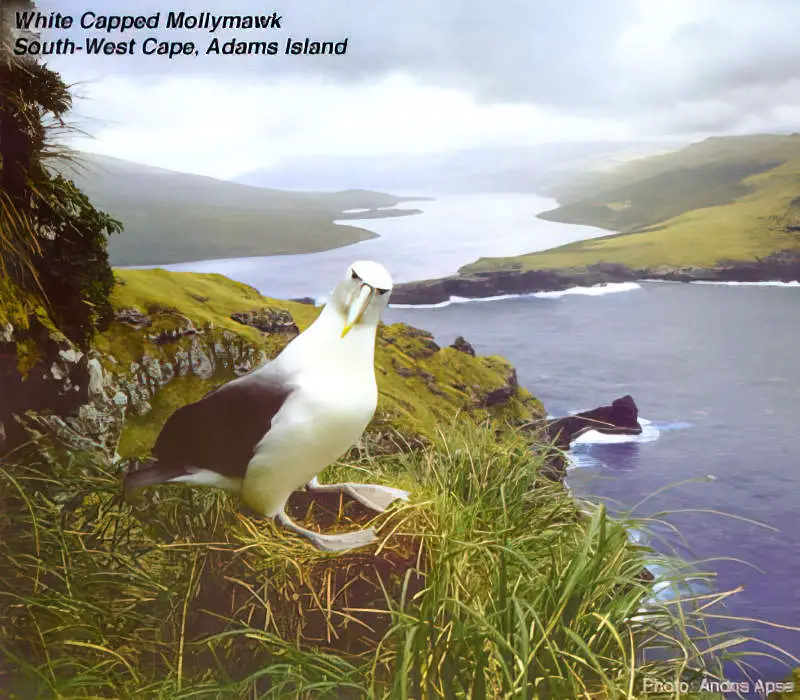

To a modern ecologist, Disappointment Island is infinitely fascinating, and not just because of the bird life. The Auckland Island Group is fascinating for anyone into flora, invertebrates, and magnetic anomalies. But to the eye of a marooned sailor in 1907, there was nothing on this wind-whipped jut of rock but tussock. Safe harbour? No. Fresh water? No. Nuts and berries? Also no. Trees? Not a single one.

Let’s not forget the birds.

The white-capped mollymawk featured in this story is known as toroa in Māori. To my inexpert eye, they look like a seagull crossed with an albatross. Sure enough, they’re related to the albatross. The narrator explains in the text that an adult mollymawk is about the size of a goose. The men ate about five of them per day. In the way typical of sailors, they call mollymawks ‘mollyhawks’ because it’s easier to pronounce.

Unfortunately, pigs, cats and rodents have been introduced to the main Auckland Island and the mollymawk population is in decline. But humans remain the biggest threat to mollymawks. Most are killed by trawl fisheries, mostly off the coast of southern Africa.

The good news: even today, not even invasive species live on the smaller Disappointment Island.

And remember I told you I lent my hardback copy of this novel to my father-in-law while he was in hospital? I didn’t know this at the time, but he was having heart surgery which made use of pigs.

The pigs which Charles and co found on The Auckland Island archipelago make for a great story in and of themselves. The Atlas Obscura podcast did a great job of summarising it.

It’s entirely possible that my father in law’s surgery was successful partly because of the Auckland Island pigs… which he read about in the book I happened to lend him.

My mother-in-law returned the book and said, “Bill hardly reads anything ever, but he read that from start to finish.”

So I dedicate the audiobook to the two Bills: The Bill who gave it to me in the first place, and the Bill who survived a few more years because of special pigs, and the scientists and doctors who study them.