Carnival: In the Bakhtanian sense, “a place that is not a place and a time that is not a time”, in which one can “don the liberating masks of liminal masquerade”.

Victor Turner, Dramas, Fields and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society, 1974

Children’s literature academic Maria Nikolajeva categorises children’s fiction into three general forms: prelapsarian, carnivalesque and postlapsarian. Prelapsarian means ‘before the fall’. Postlapsarian means after the fall.

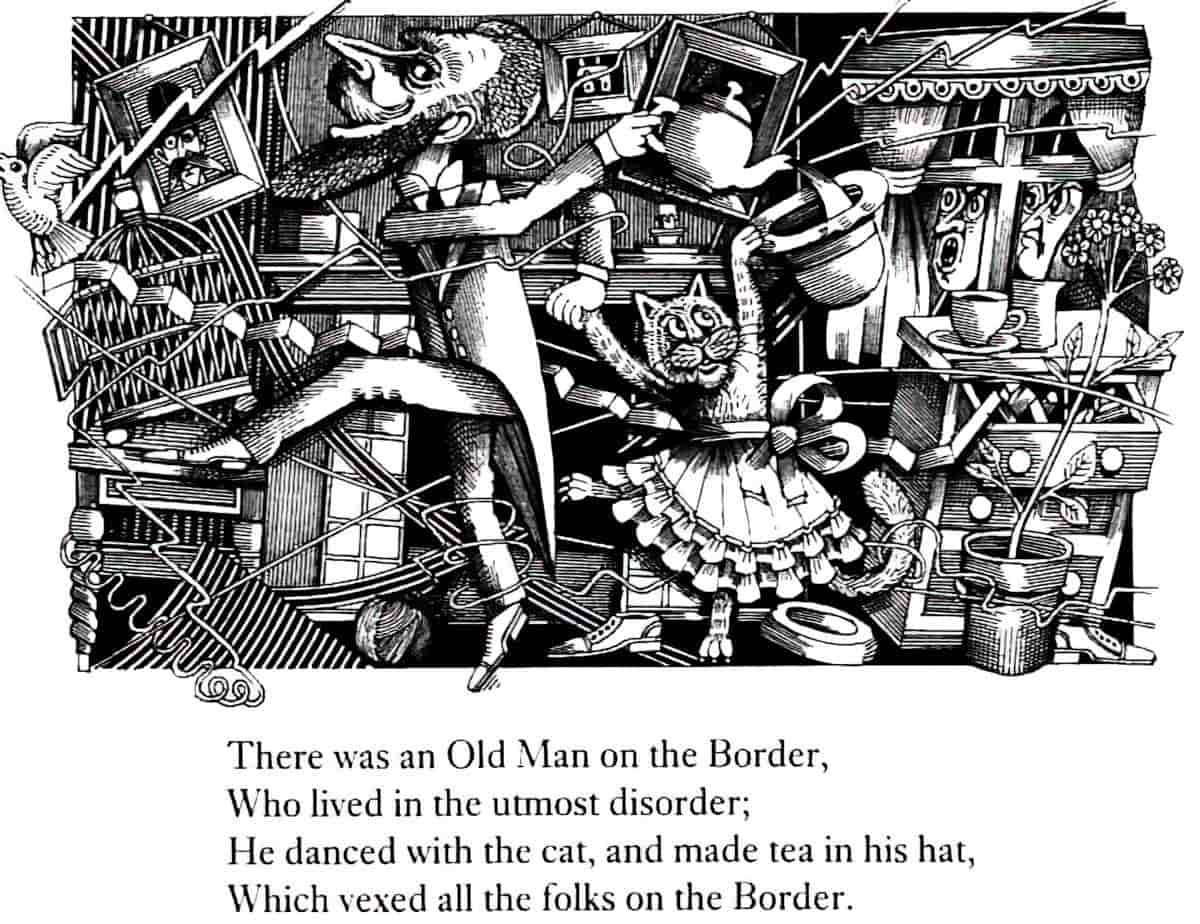

This post deals with the in-between category: stories in which characters temporarily take over from figures of authority and often make mischief, but control their own worlds for a time. These stories don’t conform to classic dramatic structure, which is why some picture books in particular seem completely off-the-wall and immune to what we generally understand as ‘the rules of story’. Carnivalesque characters don’t go through any kind of character arc, there’s no big struggle (as such) and nobody learns anything. Just as comedy goes by a different structure, so too, does the carnivalesque picture book. The carnivalesque story has quite a bit in common with comedy structure — it can only ever be short (i.e. picture book length). There isn’t enough in it to sustain a full-length novel, say.

Children are deeply curious about odd behaviors and seldom offended or worried by them. What a remarkable gift to bestow on another person, it occurs to me, and so difficult for adults to accomplish.

Vivian Gussin Paley, The Kindness of Children

BASIC STRUCTURE OF A CARNIVALESQUE PICTURE BOOK

- An Every Child is at home. There are sometimes two children, a boy and a girl. There is often just one child, coded as slightly lonely and bored, in want of a fantasy playmate.

- The Every Child wishes to have fun. That’s why carnivalesque stories often start in a place of restriction or boredom.

- Appearance of an Ally in Fun. (The Cat in the Hat turns up.)

- Hierarchy is overturned. Fun ensues. The adults are no longer in charge! The normal rules don’t apply.

- Fun builds! Somehow the author must think of a way for the fun to get wackier and wackier.

- Peak Fun! The best carnivalesque stories are displays of imagination even beyond a child’s wildest dreams. The carnivalesque story takes the reader beyond what they can imagine themselves. The hardest part of writing a carnivalesque picture book is finding an original way to end it.

- Return to the Home state. Normal and safe hierarchy resumes, with adults in charge.

In the most madcap of carnivalesque stories, there is often a pause to give the reader a breather.

I have just described your typical carnivalesque picture book for preschoolers. However, full-length novels and films for older readers do contain elements of the carnivalesque, if not hewing closely to that picture book carnivalesque story structure. Any young adult story which ‘disturbs the universe’ is carnivalesque, sometimes very darkly.

Any story about a woman who overturns the restrictions of patriarchy is also carnivalesque — witch stories, stories of pregnant women who ignore taboos around pica to eat what they like… These stories are also carnivalesque.

As you may have already deduced, the carnivalesque story is related to the tall tale, which gets wackier and wackier, and then wackier again.

DEFINING CARNIVALESQUE

In a carnivalesque story, the lowest in societal hierarchy — in the medieval carnival a fool, in children’s books a child — is allowed to change places with the highest: a king, or an adult, and to become strong, rich, and brave, to perform heroic deeds, to have power.

Maria Nikolajeva, From Mythic to Linear: Time In Children’s Literature

[…]

The necessary condition of carnival is the reestablishment of the original order, that is, return to normal life. Carnival is always a temporary, transitional phenomenon—so is childhood. Like the carnivalesque fool, the child can temporarily, by means of magic or his own imagination, become strong, beautiful, wise, learn to fly, trick the adults, and win over enemies. The end of carnival means return to the everyday, but the purpose of carnival is not only entertainment, but a rehearsal of a future moral and psychological transformation.

To borrow ten dollar words: The ‘carnivalesque’ children’s story features a plot in which child characters interrogate the normal subject positions created for children within socially dominant ideological frames.

In simpler language: A child breaks free of the rules, has fun for a while, then returns home. The carnivalesque plot is basically a home-away-home plot, even if the child never literally leaves home e.g. The Tiger Who Came To Tea, or The Cat In The Hat, in which fun walks in the door. In the Dr Seuss example, it is the mother who returns home, but the children have nevertheless been on a journey (of the imagination). The Desire of the children in these stories is simply to have fun for a while. They often start in a state of boredom.

THE REASON FOR CARNIVALESQUE

Might there be reasons beyond ‘having fun’ for the huge popularity and longevity of the carnivalesque children’s story?

A.O. Scott has the following to say about And To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street by Dr. Seuss (racially problematic):

The book is a hymn to the generative power of fantasy, a celebration of the sheer inventive pleasure of spinning an ordinary event into ”a story that no one can beat,” the recurring phrase that was the book’s original title.

Sense and Nonsense

In this way, carnivalesque stories indirectly model endurance and perseverance. Carnivalesque stories also tend to include adventure, often outside the home. Adventures show children that they are brave, independent and totally okay outside the watchful eye of caring adults.

Carnivalesque stories often have an overt moral, which is in fact undermined by its own self. (SpongeBob Squarepants also works like this.) Returning to the example of And To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street, A.O. Scott explains: “Objectively, the lesson of ”Mulberry Street” may be ”tell the truth,” but the force of the story and the pictures undermines that moral, making the book a perfect parable of the tension, so basic to the lives of children, between freedom and responsibility.”

If stories both deliver a moral and also undermine them by the way in which they’re told, children are learning that life isn’t black and white. There’s a difference between what children are told to do, and how the world really works.

FUN AND ITS FLIP SIDE: A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE WORD

Although the carnival looks like unmitigated fun, it is socially sanctioned and controlled, originally by the church. (In case you need a word to describe flip side of this: ‘abject’, which describes the taboo and whatever should be repressed.)

Originally, carnivals were particular festivals with unique rituals that mirrored and inverted the essential elements of religious meaning.

“Christmas/Yuletide laughter” was a time people were permitted to laugh. At Easter it was known as “Paschal laughter”. This was originally a pastoral phenomenon, inextricably linked to a Christian phenomenon, designed by the church to cheer up the congregation. (A good word to use for rituals of this era is ‘Christianized’ — ‘adjusted to Christian beliefs’.) Paschal laughter was first mentioned in texts in the early 1500s. The priest would tell jokes from the alter to cheer everyone up. (Maybe this is related to April fool’s jokes.) At all other times people weren’t permitted to laugh in church. Laughter and ridicule were to a certain extent legalised and tolerated on other holidays as well. That’s why the rich body of parodic literature from the Middle Ages is connected to celebrations and holidays.

Carnival tales are best considered to have two sides. These tales celebrate the two most significant stages of human existence: birth and death. In stories for adults, the events of the story are seen as a rebirthing and a reaffirming process for the renewal of society. Think of a body in two different ways: One is to do with birthing and dying. The other is conceived, generated and born. Creation or destruction, one or the other at any given time.

In religious terms, one is seen as a vessel (a temporary state before salvation), the other is corporeal and organic. This is why churches focus on saving the soul. (This view of bodies has been historically terrible for women. Men also have bodily functions, but with women’s grotesque and confronting childbirth or regular bleeding, women’s bodies are a constant reminder that humans are corporeal, not magical.)

THE FIRST CARNIVALESQUE STORY

In the Hebraic tradition, it’s probably the Adam and Eve story: the ‘adult children’ prance about in an Arcadia, and do something they know they’re not supposed to do — eat an apple. They’re trying to discover where the boundaries lie.

John Milton seemed to like that story, too, with Paradise Lost — a poem about the ‘arch transgressor’ Satan. Milton was himself transgressive. He was anti-clerical, a radical heretic and a political revolutionary.

In Hellenic myth we have Prometheus and his transgressive bestowal of fire upon humanity.

In both the Hebraic and Hellenic traditions, the ‘birth of imagination’ came from an act of rebellion against the divine order of things. In Western culture, transgression and imagination are strongly linked.

THE CARNIVALESQUE AND SHAKESPEARE

Shakespeare is just one example of a storyteller who has played with the carnivalesque. For instance, all the spells and enchantments in William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream create a carnivalesque atmosphere for the lovers in which the normal rules of life just don’t apply.

THE FOUR TYPES OF CARNIVALESQUE

[The carnivalesque] is a form that Bakhtin identifies as historically playing an active role in challenging authoritative language and values. With its roots in actual popular-festive forms of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, the carnivalesque’s power as a direct social force was greatly diminished with the advent of bourgeois culture; it continues, however, to live in literature, and, for Bakhtin, finds its paradigmatic expression in the works of Rabelais. The carnival and narrative modes featuring the carnivalesque work to challenge the hegemony of the official culture and its monological language by uncrowning authority and subverting normal hierarchies. The carnivalesque blurs the boundaries that normally exist between orders of discourse and between classes. It abolishes the distinction between observer and participant, between satire and the object of satire.: there are no footlights in carnival, participants are simultaneously actors and audience, and all is dissolved in general laughter.

John L. Kijinski, “Bakhtin and Works of Mass Culture: Heteroglossia in Stand By Me“, Studies in Popular Culture, Vol. 10, No. 2 (1987), pp. 67-81.

Mikhail Bakhtin was a Russian critic and philosopher. Bakhtin’s ideas are an evolution of the work of Francois Rabelais. For Bakhtin, the carnivalesque concerns everything that middle-class people with good manners don’t talk about, the lower part of the body, farts, pigs, untidy and unclean environments and anything which reminds us that humans are just another type of animal.

Mikhail Bakhtin’s four categories of the carnivalesque world:

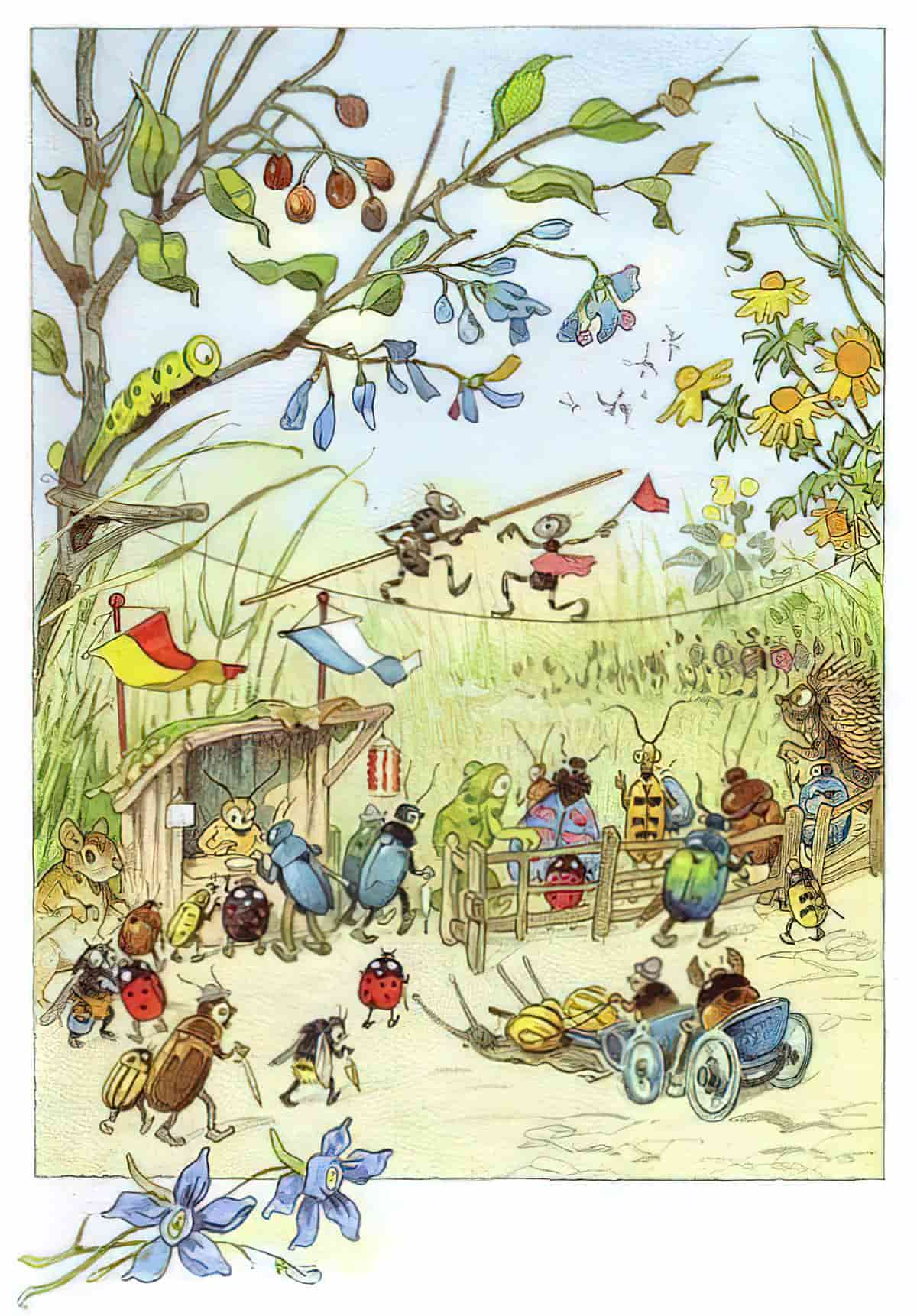

- Familiar and free interaction between people: Unlikely people are brought together. They interact and express themselves freely.

- Eccentric behaviour: Unacceptable behaviour is welcomed and accepted. A character’s natural behaviour can be revealed without the consequences. (The idea that there’s a wild inner person behind a thin veneer is a Freudian way of looking at psychology.)

- Carnivalistic misalliances: Everything that may normally be separated reunites. Heaven and Hell, the young and the old, the powerful and the low-status, the rich and the poor, humans and animals etc.

- Sacrilegious: Carnival allows for sacrilegious events to occur without punishment. These plots are creative theatrical expressions of manifested life experiences in the form of sensual ritualistic performances.

CARNIVALESQUE TALES FOR CHILDREN

Though Mikhail Bakhtin had four categories, John Stephens divides carnivalesque texts for children into three main types:

- Those which offer the characters ‘time out’ from the habitual constraints of society but incorporate a safe return to social normality (of which Where The Wild Things Are is one such example). Adults tend to be not present to intervene.

- Those which strive through simple mockery to dismantle socially received ideas and replace them with their opposite, privileging shortcoming over strength (Babette Cole’s Prince Cinders, Anthony Browne’s Willy The Wimp, Fungus the Bogeyman by Raymond Briggs)

- Those which are more recent, and perhaps British in origin, consist of books which are endemically subversive of such things as social authority, received paradigms of behaviour and morality, and major literary genres associated with children’s literature (Out Of The Oven by Jan Mark and Anthony Maitland, Wagstaffe the Wind-up Boy by Jan Needle).

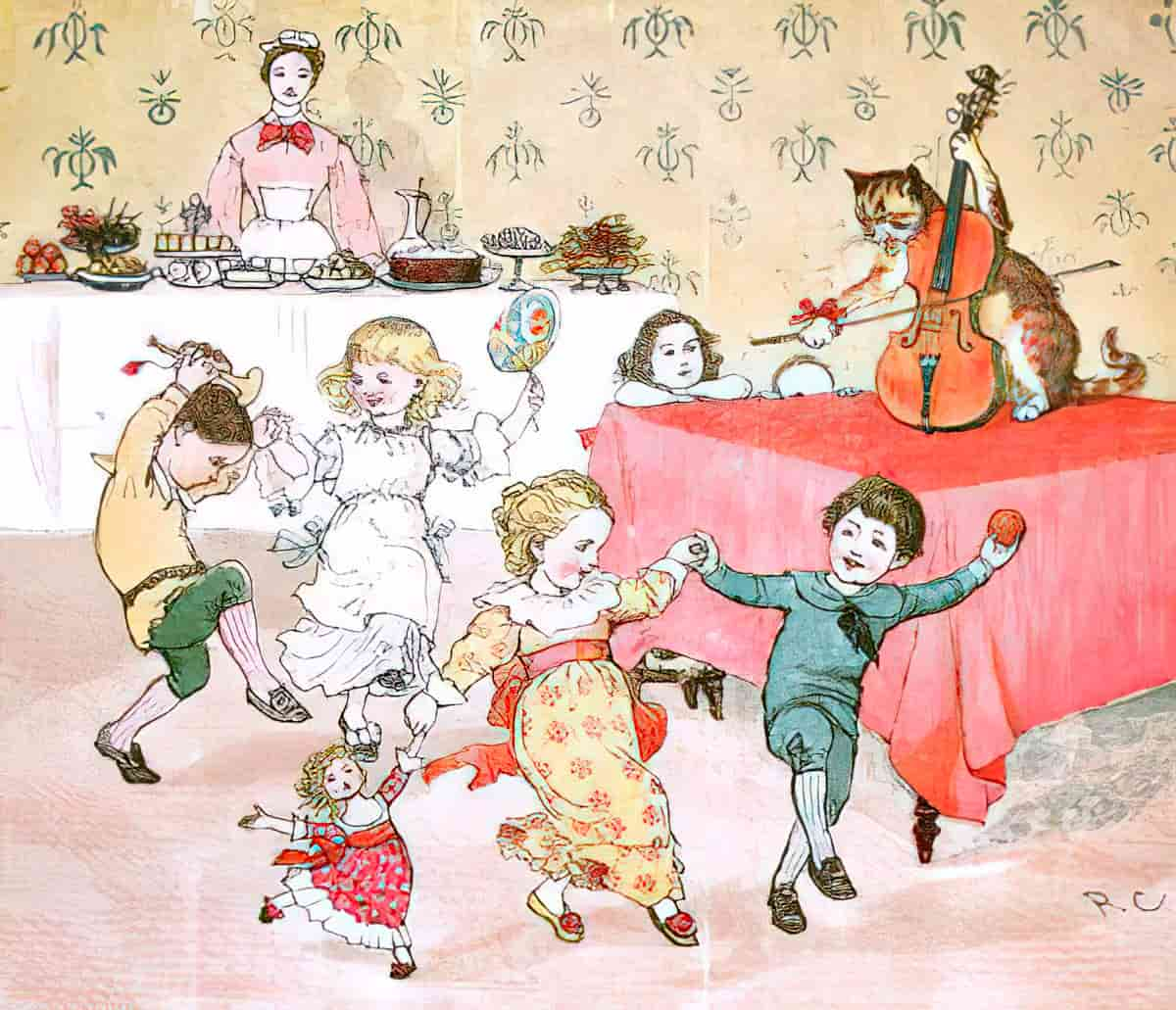

Carolyn Daniel, in Voracious Children, explains that texts that transgress adult food rules generally fall into either the first or third of these types. For more on the importance of feasting in children’s literature, see Sex Equals Food In Children’s Literature. The feast is an important subgenre of the carnivalesque.

In pre-bourgeois society, this popular-festive form was grounded in the cycle of labor and harvest: “The popular images of food and drink are active and triumphant, for they conclude the process of labor and struggle of the social man against the world.” At the center of the feast is the human body, presented through images of grotesque realism, which include exaggerated representations of eating, drinking, excreting, vomiting, and talking — all done in a comic and positive light. These grotesque images link the body to the earth and thereby uncrown authoritative hierarchical distinctions by reminding us that we are all of the earth, a fact that should be triumphed in rather than masked and mystified: “The limits between man and the world are erased, to man’s advantage”.

John L. Kijinski, “Bakhtin and Works of Mass Culture: Heteroglossia in Stand By Me“, Studies in Popular Culture, Vol. 10, No. 2 (1987), pp. 67-81, quoting from Rabelais and His World

It’s all related to this concept of carnival, which points earthwards rather than heavenwards. Eating and other bodily functions are to do with Bakhtin’s “material lower body stratum”.

THE CARNIVALESQUE STRUCTURE

This structure is seen frequently in picture books for young readers. But stories for adults will frequently include a carnivalesque interlude.

For example, in the 1986 coming-of-age film Stand By Me, Gordie tells a story-within-a-story when the four main characters spend the night in the forest. A fat, bullied, ostracised boy called Davie throws up all over everyone at an exploitative pie-eating contest. This highlights Gordie’s ideals about equality and fairness. We can think of this story-within-a-story as a carnivalesque interlude.

An Every Child is at Home

This part of the story may be cut off.

The Every Child wishes to have fun.

This part may also be omitted, especially in newer picture books with tighter word limits.

- Common motifs: The child looks out of a window (typically on a second-storey floor) or sits on the fence at the edge of their property.

- Although childlike characters desire fun, Courage desires status quo. He has an anxious disposition. In this case, the childlike audience desires the fun on his behalf.

Disappearance or backgrounding of the home authority figure

Some carnivalesque stories begin with no adults around. We can assume they are there, though, waiting to embrace the child when the child returns from their adventure into imaginative independence.

- In Courage The Cowardly Dog Muriel is always around, but because she is so short-sighted she’s hopeless as a protector.

- Children’s authors have come up with many ways to get rid of parents, especially mothers. (Fathers and grandparents are more likely to join in the carnivalesque fun due to the Female Maturity Formula which influences storytelling.)

Appearance of an Ally in Fun

When I say ‘fun’, sometimes these stories are scary.

- The Cat In The Hat (Dr Seuss)

- Zachary Quack (Lynley Dodd)

- A burglar who likes to ride pigs (Kate diCamillo)

- A tiger who enjoys English high-tea parties (Judith Kerr)

- A crocodile under the bed (Ingrid and Dieter Schubert)

- A boa who turns up during an otherwise boring school excursion and eats all the washing on the line (Hakes Noble and Kellogg)

- A flying snowman (Raymond Briggs)

- Annoying, possibly pestilent characters who move into your house and refuse to leave.

- In The Farmer and The Clown by Frazee, a toddler is the character who shows up to change the life of a lonely old farmer. This is an unusual age inversion.

- Many episodes of Courage The Cowardly Dog are carnivalesque structures in which an ominous stranger arrives at Courage’s house in the middle of Nowhere. (Occasionally Courage goes out into the world.)

Hierarchy is overturned. Fun ensues.

We might also call this ‘the uncrowning’.

- Sometimes a literal crown is transferred to the child character, for example in Where The Wild Things Are.

- Z is for Moose by Kelly Bingham and Paul O. Zelinsky is an interesting case because rather than ‘fun’, the main character has a full on temper tantrum. However, this is very fun for young readers to watch.

- A small fish steals a much larger fish’s hat and doesn’t even feel bad about it. (Jon Klassen)

Fun builds!

Typically, objects or characters multiply.

- It might be many, many cats.

- It might be a sandwich that gets bigger and bigger and bigger.

- It might be increasingly ridiculous things stuck in a tree.

Although fun builds, this doesn’t necessarily mean pandemonium. Some carnivalesque stories are quiet, especially those featuring girls, for instance When The Sky Is Like Lace by Horwitz and Cooney.

In President Squid by Aaron Reynolds, the ‘fun building’ segment is an increasingly ridiculous and lengthy list about why a monomaniacal squid would make an excellent president.

Peak Fun!

Something happens to bring all this fun to an end. For lack of more original ideas, perhaps the adult caregiver returns, interrupting the carnival. Ideally it’s more original than that and leads seamlessly into the next phase, which is the most taxing part of the story for writers…

Surprise! (for the reader)

Given time and guidance, almost anyone can create a carnivalesque story for themselves… until this point. This is where the story really calls for imagination and originality. Not all published and popular stories contain a ‘surprise’, as such, but the most popular contemporary carnivalesque picture books do. Parents are typically reading their young children three or five picture books per night at bedtime rather than a single long story, and each of these stories functions a bit like a gag. Picture books are 200-300 words now, not 1000.

Of course, after the first reading, the gag is no longer a surprise, yet a picture book may be read fifty times over. The picture book gag must be so good it has anticipatory merit. It can’t be a one-time groaner.

White American male writers are well (over?) represented in the gag category of carnivalesque picture books: Think Mo Willems, Aaron Reynolds, Oliver Jeffers, Jon Klassen.

Return to the Home state

The home ‘state’ doesn’t necessarily mean ‘home’, but in your classic carnivalesque picture book, the child will be tucked up safely in bed. Key here is the sense of safety.

Not all storybook characters return home safely.

- Jon Klassen’s small fish meets a sad end.

- Ditto The Gingerbread Man (If you want to enjoy a carnivalesque jaunt, pays not to be delicious.)

CORPOREAL DISCOMFORT

Gross-out books are also a subcategory of carnivalesque tales, focusing on bodily functions. During childhood we learn to come to terms with how the body works, which parts are private. (There is still a dearth of literature which affords the same level of comfort with menstruation compared to the other bodily functions. That said, I wouldn’t like the ‘gross out’ treatment for menstruation, because of a long history of taboo and disgust around women’s body.)

Series such as Diary of a Wimpy Kid are not gross-out books per se, though characters like Fregley seem to revel in it. There are regular scenes in which Greg Heffley is disgusted by the human body, for instance when he visits the local pool. He is of course terrified of impending puberty.

The PhD thesis by B.F. Haynes (2009): Elements of Carnival and the Carnivalesque in Contemporary Australian Children’s Literature. The work of Paul Jennings and Andy Griffiths comes up again and again. These two authors have ‘focalised the role of bodily functioning as narrative device’.

The time for gross-out books is limited to a very narrow window of childhood (and some kids never enjoy them at all). What does this turn into? Well, discomfort with living in a body doesn’t disappear. In young adult literature it simply takes a different form.

The Bakhtinian concept of the medieval grotesque — a dark focus on the corporeal — combines easily with the carnivalesque in adolescent literature because of adolescents’ extreme anxieties about their physical bodies.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Disturbing The Universe

As stand-out examples, Trites offers the works of:

- Judy Blume

- M.E. Kerr

- Hadley Irwin

- Richard Peck

Each of these authors ‘could be read as jesters parodying the adolescent body.’

FEATURES OF CARNIVALESQUE CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

- is playful

- is non-conforming

- opposes authoritarianism and seriousness

- is often manifested as a parody of prevailing literary forms and genres often has idiomatic discourse

- is often rich in language which mocks authority, even though swearing is taboo in children’s literature (for example Dahl’s use of ‘pulled a pistol from her knickers’)

- often stars a hero who is a bit of a clown or a fool

Maria Tatar has pointed out that children’s characters often begin from a place of boredom:

Look closely at children’s books and you will find that the heroic child often begins as a bored child, a child faced with the challenges of coping with the tedium of everyday life. … Oddly, the bored literary child often touches magic by falling asleep and dreaming about places like Oz, Wonderland, or Neverland. In real life, relief comes in the form of a setting rather than sleep.

Maria Tatar, Enchanted Hunters

Which — again — goes against much advice to writers — to create go-getter characters who want something specific and then go for it. Carnivalesque characters are different. They are generally just a stand-in viewpoint character for the child reader, with no real distinguishing characteristics of their own except for a fun body type (an animal in clothes, a rogue pet etc). These children have no more distinguishing characteristics than your average picturebook moose.

However, carnivalesque main characters can also have highly individuated characterisation. It depends on what the storyteller wants the book to be. Is it a story about pure fun (less individuated) or is it a story in which the character learns something (more individuated, starting out with shortcomings).

COMMON CARNIVALESQUE CHARACTER ARCHETYPES

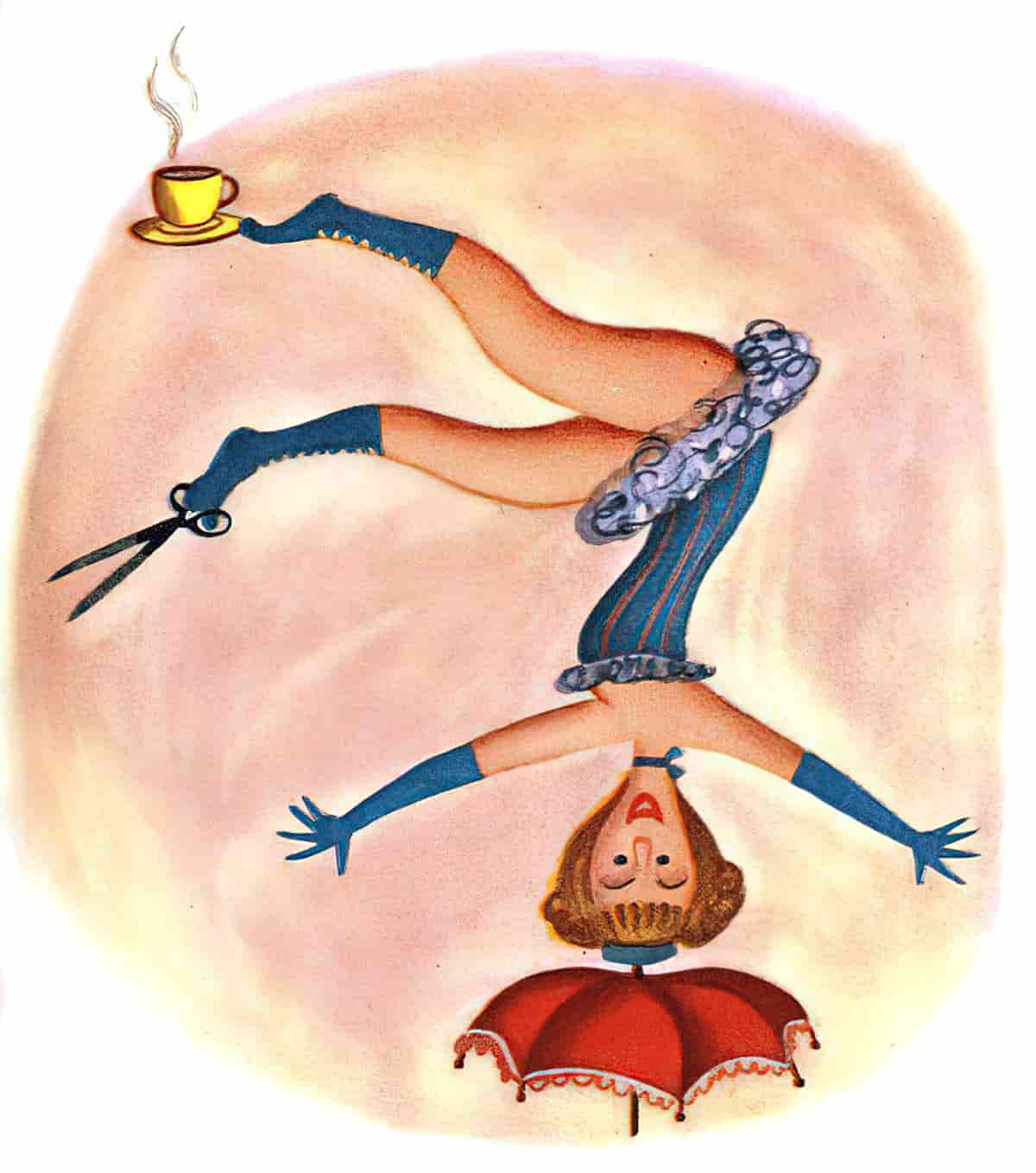

The fool is a useful character archetype in a carnivalesque tale.

- The fool is most often gendered male.

- The fool is free to speak the truth as he sees it but in turn usually reflects those believes of the society he mocks.

- In the upside-down setting of the carnivalesque, the fool provides the opposition to established order.

- The fool provides laughter for everyone. Laughter negates authority. Bakhtin said that the fool ‘speaks the laughing truth’. (You can probably think of real life examples of people with large platforms, who alternate between ‘speaking the truth’ and also saying outlandish things.)

- The fool’s message might be farce, satire or parody.

- As you can see, the fool is rarely made of pure stupid. This character is almost mandatory in any successful comedy. Seinfeld’s Kramer is alternatively naive and also lives outside mainstream society and is therefore able to see some of its absurdity, revelling in fun inside his own apartment by setting up a wonderland replete with spa pool and so on, focusing heavily on his stomach (food). In SpongeBob Squarepants, Patrick is alternately flat out wrong about basic truths but as the story requires he is able to point out a lot of truths to SpongeBob, who is a different kind of naïve. In Kath and Kim, Kath quite often has a handle on the real situation and is able to give pretty good advice to the younger women in the show, namely Sharon and Kim.

- Bakhtin has broken the particular stupidities of the fool down into further subcategories:

- simplicity (Patrick of SpongeBob Squarepants)

- naivety (Kel of Kath and Kim)

- generosity (Sharon of Kath and Kim)

- misunderstanding of pernicious social convention (today sometimes coded as autistic)

Of course, every fool needs his ‘straight man’, so the King archetype is equally necessary in carnival. Another take on the King archetype is the Lord or Abbot of Misrule — the leader of youth groups who were important in organising processions, competitions etc.

Misrule doesn’t have to be a ‘fool’ — jesters and clowns are related archetypes.

CARNIVALESQUE OBJECTS

Carnivalesque characters are often given props with which to have fun.

- Umbrellas are surprisingly common carnivalesque props, especially when they are not used for keeping rain off.

- Flight is very common in carnivalesque fantasy, so a character may take flight using any number of things: balloons, bubbles, flying carpets and so on.

- Where things are repurposed in original ways, this may be an indication of carnivalesque. In Where The Wild Things Are, the saucepan becomes a crown, which highlights the absurdity of the props of hierarchy. Speaking of Max…

WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE

Where The Wild Things Are is [the first kind of carnivalesque text in three important ways: Max’s behaviour is oppositional to normal socializing expectations; the ‘wild things’ in the illustrations are grotesques, and thus in essence parodies of the natural creatures usually encountered during a wilderness adventure; and the book clearly belongs to the ‘time out’ group, in that Max’s adventure is formally a parenthesis in his relationship with his mother. Roger H. Ford (1979) has suggested that the main characters in several of Sendak’s books are modelled on the folk-tale Trickster figure, dominated by selfish appetites and emotions, given to practical jokes, capable of heroism and generally unselfconscious. Max’s entry into the land of the wild things, whether we regard it as a dream or an act of the imagination, enables him to enjoy a time of unconcerned spontaneity free of the social constraints which define his behaviours in the world as ‘mischief’. Max’s attempt to construct a site for fantasy play in the opening illustration involves causing damage to property, as is foregrounded by the grossly oversized hammer with which he attempts to drive a huge nail into the wall. His second act of mischief is to attack the family dog with a kitchen fork, an actual breach of proper conduct going beyond the quasi-‘hanging’ of his teddy bear included in the first illustration. Max, then, still deeply immersed in the solipsism of childhood, has not yet learnt the first principle of freedom—that freedom of action is bounded by the rights of others. Carnivalesque texts, by breaching those boundaries, explore where they properly lie and the ideological bases for their determination, but without always necessarily redrawing those boundaries…The grotesque in this book is comic and droll rather than frightening, though this was not always perceived when the book was first published. …By giving comically grotesque forms to inner fears, the illustrations image the defeat of that fear. Moreover, Max is always in control. Swanton (1971) offers this as one reason why children do not find the book frightening.

Language and Ideology in Children’s Fiction by John Stephens

John Stephens explains that the carnivalesque story is used not to question the values of the official world (that children being rude to their mothers needs to go punished before they are allowed to eat dinner), but to ‘define the values which may be at most implicit in some of the puzzling actions performed by those in power. In this respect, it is important to see that Max’s return and his mother’s gift of ‘supper’ are not causally linked but contiguous, since each is unconditional.’ Other authors of the era were writing quite different stories re parent/child power. For example, E. Nesbit. Stephens points out that modern books are not necessarily any better than Nesbit’s were, in that regard.

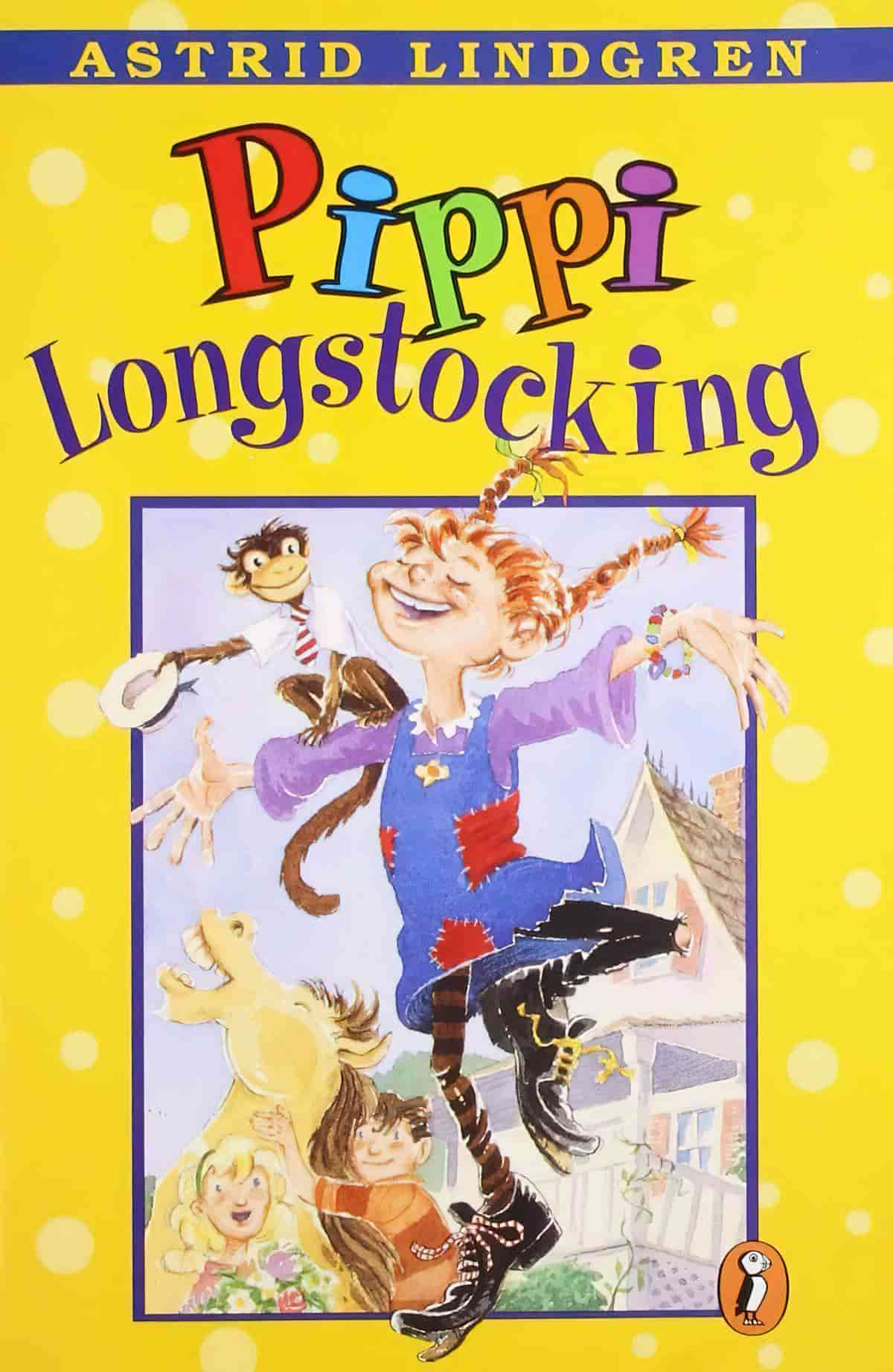

PIPPI LONGSTOCKING

Pippi Longstocking, Swedish favourite, is the ultimate carnivalesque character, and a rare female example. Ramona Quimby, Junie B. Jones and various new female stars of chapter books and middle grade are filling a bit of a hole there, but I have heard literary agents lament that they have all but disappeared by the time the reader advances to young adult literature. If carnivalesque female characters exist, they tend to be the main character’s best friend.

CURIOUS GEORGE

You’ll notice in the picture below, carnivalesque children’s characters are often depicted in mid-air, mid-mischief. By the way, the inverse of a carnivalesque character is the underdog. Readers also love underdog characters, so long as they break free of that status.

THE CAT IN THE HAT BY DR SEUSS

The O.G. of carnivalesque picture book characters.

In The Cat In The Hat, Theodore Geisel (Dr Seuss) slyly revealed that discipline and anarchy live on opposite sides of the same street. (Cheersome fact for writers: Though fun to read, it took a year and a half of struggle for Geisel to write.)

PETER PAN AND WENDY

The Darling Children, like their more anxious counterparts in The Cat In The Hat, move from the orderly routines of a space ruled by their mother to rowdy antics and alluring adventures in a setting that bears a distinct resemblance to the way we imagine the mind of a child.

BUGS BUNNY

The stand-out carnivalesque character from retro cartoon world would be Bugs Bunny, who is all about fun and over-turning whatever social hierarchy is in place.

NOT ALL CARNIVALESQUE IS FUN

Now I’ve given you all those examples of laughing, prancing characters, remember what I said above about the dark flip side of carnival.

The Chocolate War by Robert Cormier is not a fun novel. Yet we use this story as a young adult literature example of the carnivalesque. When the main character decides not to sell chocolates, he is rebelling against the authority of an institution. This ultimately leads to his downfall. Perhaps a good way of summing up the carnivalesque is simply ‘disturbing the universe’.

In fact, the carnival is a way for people — including children — to come to grips with scary things.

Children are frequently involved as subjects and players [in carnivals], and not only during Halloween. Guaranteeing their survival is a central part of the story, and different festivities face up to dangers that can assail from any number of directions—sickness, animal predators, witchcraft, devils, cannibals, ogres, succubi, fire and flood and famine. The magical attempt to secure safety takes two predominant forms: either the participants impersonate the danger itself, as in the carnival masks and fancy dress of Halloween, and thus, cannibal-like, absorb its powers and deflect is ability to inflict harm; or they expose themselves and by surviving the ordeal, prove their invulnerability.

Marina Warner, No Go the Bogeyman

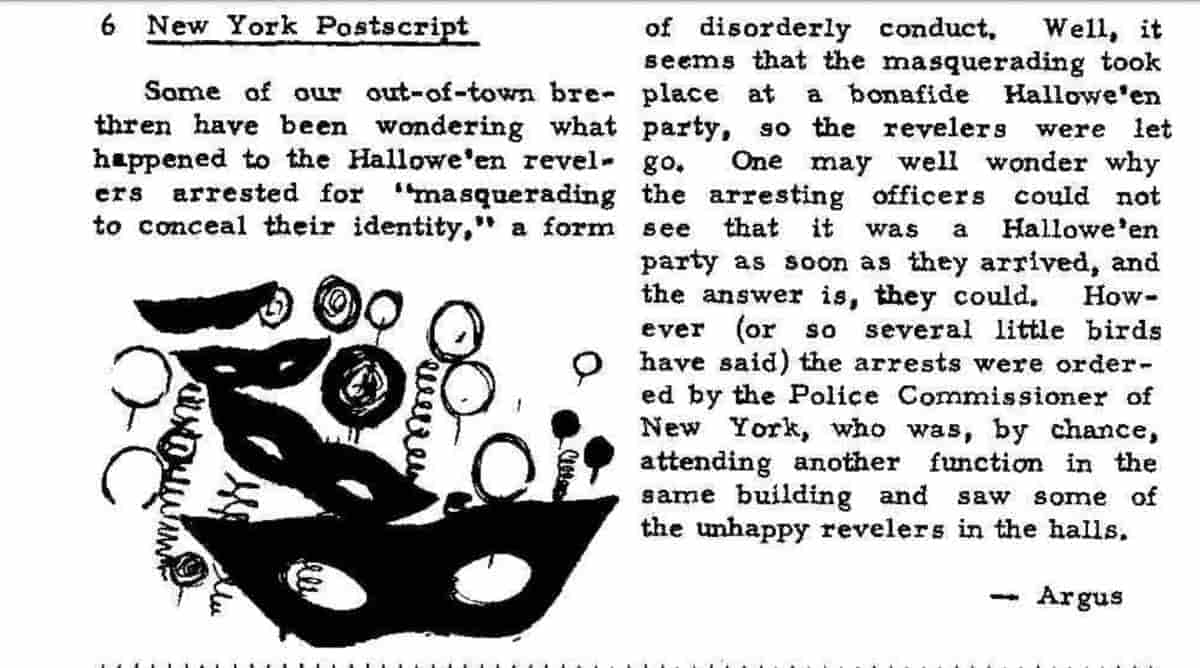

Halloween has historically super important to queer communities as well, as explained below by Eric Gonzaba:

Not to over-romanticize this, but gay people loving Halloween isn’t some accident. Up until the 1970s, most US cities banned same-sex dancing (and serving booze to gays, and even simple touching.) But in the 1950s and 60s, some police departments made exceptions for Halloween and New Years.

This wasn’t universally true, of course. The Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) infamously raided the Black Cat just after midnight hit on New Years in 1967, arresting sixteen for “gross indecency” likely for kissing a lover at midnight. Two of those arrested had to register as sex offenders for the rest of their lives.

On Halloween, though, it was possible to get around some of these laws. For example, in cities that banned drag (and enforced it by demanding men not wear clothing deemed “feminine,”) it was easy to defend one drag as a simple Halloween costume on Oct 31.

Here’s New York Mattachine newsletter (an early gay rights group) informing members the status of those arrested for drag in 1962. The police let them go because….. it was Halloween!

@EGonzaba

Political organizing into the 1960s and a growing confidence that they weren’t sick lead gays to more brazenly challenge homophobic laws. As one activist in SF put it in 1973, “We were allocated Halloween and nothing else. Finally, the gay community said ‘Fvck you.’”

“We’re going to put on a dress anytime we want to.” So yes we homosexuals love Halloween because it’s campy, silly, outrageous, blah blah. But that’s the point. All this wasn’t legal just a few generations ago. Go party. Happy Halloween

@EGonzaba

Public Performances: Studies in the Carnivalesque and Ritualesque

Public Performances: Studies in the Carnivalesque and Ritualesque (University Press of Colorado) offers a deep and wide-ranging exploration of relationships among genres of public performance and of the underlying political motivations they share. Illustrating the connections among three themes—the political, the carnivalesque, and the ritualesque—the volume provides rich and comprehensive insight into public performance as an assertion of political power.

New Books Network

Like a lot of literary theory, the concept of carnivalesque literature works on a number of levels. The first of these is pure inspiration; it’s a source of striking narratives and imagery that can spark ideas and add to your narrative. The second is as an observation of societal behavior – the carnivalesque describes a consistent model of cause, effect, and motivation that, if understood, allows authors to imbue fantastic events and settings with a feeling of deeper reality. Thirdly, the carnivalesque can be applied directly to the relationship between author and reader, allowing you to give your reader something they’re not even aware they want, as well as letting you steer their expectations so your narrative is as effective as possible.

What Authors Need To Know About Carnivalesque Literature by Robert Wood