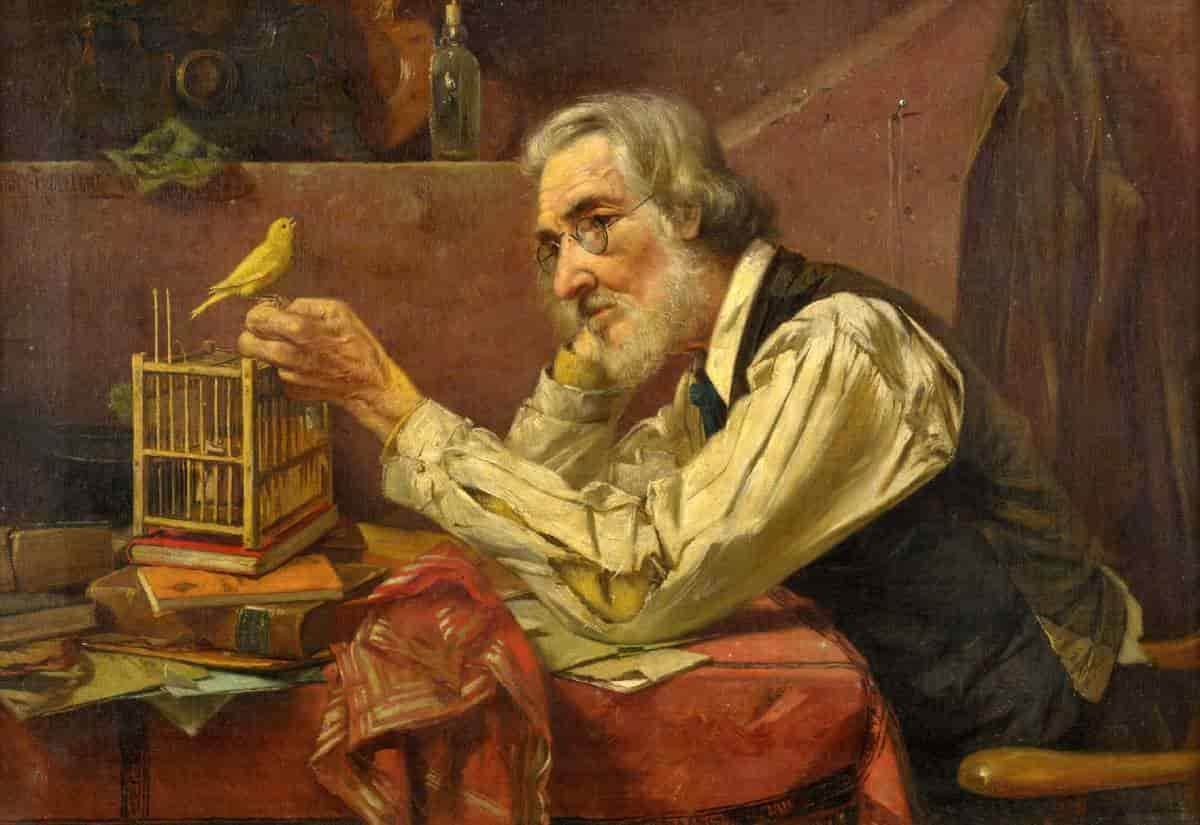

“The Canary” is a short story by Katherine Mansfield, and the last she ever finished. It was published in April 1923, after she had already died. “The Canary” was then collected in A Dove’s Nest.

When Mansfield wrote this she was very ill with tuberculosis. She started writing it when she and her husband Jack (John Middleton Murry) were staying at a hotel in Paris. A woman living across the road from this hotel kept canaries. Mansfield managed to finish writing the story when staying at a different hotel, this time in Switzerland.

Locked up herself due to ill-health, it’s easy to imagine Mansfield felt empathy for these caged birds, which might explain the extent to which she anthropomorphises them. However, it’s tempting to read “The Canary” only as the last words of a writer on her death bed. The story is more than loneliness and sadness. This is satire.

BIRDS AND THE SOUL

Roy Orbison also did a cover of “The Little Bird”, though my favourite cover is by Australian Tex Perkins, which appears in the soundtrack to Beautiful Kate.

What is it about birds, then? In Katherine Mansfield’s “The Canary”, as well as in Marianne Faithfull’s “This Little Bird”, the small bird represents the human soul, sometimes on the ground, sometimes disappearing in that liminal space we call sky, finally leaving us to disappear into the Heavens. This birdie-soul symbolism is hardly new. It wasn’t new when Katherine Mansfield used it, and wasn’t new when Marianne Faithfull used it. It seems small birds were made for such symbolism. (Note that it only works for SMALL birds. LARGE birds carry completely different symbolism, as do birds which feast on carrion.)

NARRATION

“The Canary” is one of Mansfield’s first person stories — a theatrical piece, basically a monologue. Impersonated speech underscores the loneliness of the landlady. At times the narrator speaks directly to the audience. ‘Have you kept birds?’ This breaks the fourth wall but in an ostentatious, laughable way, which reminds me of the Goth from The I.T. Crowd, who is obviously a parody of Gothic fiction.

In 1997, Pamela Dunbar pointed out how it’s too easy for readers to focus on the emotions Mansfield stirs up in readers and completely miss the irony. Dunbar used “The Canary” as an example:

Mansfield is here tilting at the traditional view of love as inspired by the charms of the lover. The heroine, herself an adept student of emotion, makes the point: I loved him. […] At the same time, by making a bird the object of her heroine’s emotions, the author allows the pathos of her portrait to dip over into the grotesque. In this story emotional complexity resides, not in the psychology of the key figure but in the irony of the presentation. Romantic in her emotional reach and in her association with a songbird, the narrator is disqualified by her sex and lack of social status from the exalted status of the Romantic poet.

Pamela Dunbar, Radical Mansfield: Double Discourse in Katherine Mansfield’s Short Stories (1997)

It’s especially tempting to miss the irony of “The Canary” when you know, and Mansfield knows, that she is about to die. Good to know Mansfield maintained a keen sense of irony right until the end. People deal with imminent death in various ways. Mansfield made fun of her own maudlin attitude and wrote short fiction comparing her situation to the melodrama of a Romantic poet. (I aim to do the same.)

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE CANARY”

SHORTCOMING

HOW OLD IS THE NARRATOR?

I’ve deduced the main character is a landlady because she makes dinner for three young men. (Not hard to work out.) The fact she refers to the men as ‘young’ tells us she is no longer young herself. Commentators assume an ‘elderly woman‘. But I don’t get ‘elderly’ at all. The voice is too young, and the story seems like a deliberate pushing-away of romantic expectations. No one has any expectations of romance when it comes to genuinely elderly women — the elderly are desexualised. Any single woman over the age of twenty-five would have felt her age keenly when the social expectation was to marry and bear children, end of. She could’ve been Mansfield’s age, in her early thirties. The young men may have been in their early twenties. The landlady is old for a single woman.

True, the story itself encourages us to think of the narrator as elderly. The narrator says things like, “I have much to be thankful for” and, “It surprises me even now to remember how he and I shared each other’s lives.” This is the sort of thing a widow might say after a long marriage. Of course, a canary’s life is short. That’s the joke of it. The narrator feels like an old lady. She feels she has lost a lifelong companion.

(Looked it up for you. Canaries have an average lifespan of 10-15 years. We have no idea how old the bird was when ‘the Chinaman’ sold it to her.)

MANSFIELD’S SPINSTER ARCHETYPE

I get the sense of a Beryl character (from the “Prelude” trilogy). Spinster Aunt Beryl also likes to look out her bedroom window and imagine a Romantic scene. Whereas Beryl imagines dashing lovers, the unnamed heroine of “The Canary” makes do with a bird. Which is safer, I think, until the bird falls off its perch.

I’m guessing the young men call the narrator ‘Missus’ not because she is or was ever married, but because all cooks and housekeeper-types were called ‘Missus’ in those days. (If you’ve seen Downton Abbey, you’ll know that Mrs Hughes isn’t married and never was. The Mrs was due to her role doing the sorts of stuff associated with housewives. Separately, ladies’ maids were addressed by their last name only, no honorific.)

QUEER LONELINESS

I’m also reminded of the picture book Owl At Home by Arnold Lobel. Owl, too, is extremely lonely, and finds solace in a personified moon. Is it a coincidence that Lobel, like Mansfield, was queer? The loneliness of sublimated queerness is a particular feeling, and may be especially well-suited to certain kinds of literary expression.

The narrator of “The Canary” is femme coded, and I like to think she is a trans woman. I have absolutely no evidence to back this up. I also have no evidence she is not a trans woman, aside from the fact she does not fit the young men’s idea of acceptable femininity — ‘The Scarecrow’ — and she doesn’t really leave the house, possibly for safety reasons. Obviously, if she were trans, she had no access to gender affirming health care and surgeries, so she would almost certainly be visibly trans.

Better, perhaps, to consider this story a trans allegory.

DESIRE

It’s easy for the normative mind to imagine this woman wants a male lover, to settle down and bear his children but that would be quite an assumption when it comes to Katherine Mansfield, queer icon. I don’t believe Mansfield especially wanted any of that for herself, and didn’t seem to want that for her female characters, either. Falling in love with a bird is one way of dealing with one’s own queerness in a world where a publicly queer identity is impossible. I’m not allowed to live how I want? Fvck it. I’ll make do with a canary. Let them laugh at the crazy bird lady.

Perhaps Mansfield is also parodying the extent to which women are associated with birds across culture and literature. (Mansfield herself made much use of birds and their connection to femininity. I wouldn’t be surprised if she looked back at the end of her life and thought some of her analogies were a bit on-the-nose. We do know that by the time she died, she’d fallen out of love with her German pension stories, and considered them bad.)

OPPONENT

I must agree with the neighbour lady who points out that birds aren’t much company. She’d get more out of a terrier. But that wouldn’t be funny, would it. Falling for a canary is on about the same level as falling for a goldfish. It’s like Tom Hanks in Cast Away falling for his Wilson ball.

The entire point of “The Canary” is that canaries can’t love you back. Nor can they reject you, though, unlike the three young men who board with the landlady. The men serve to show how the landlady is treated in the romantic marketplace more generally.

PLAN

No plan to pursue romance. Pursue birdy instead.

This story is an anti-romance and I’m here for it.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Others mock the landlady but the bird simply tilts its head. In a straight romantic story, the bird would serve as a romantic opponent (a human man). The canary doesn’t give a sh*t about the landlady, and turns the plot into an anti-struggle. There is literally no one to moon over. She’s got the bird right there, under her command. All she needed to do was buy it from the Chinese door-to-door salesman. Note: she didn’t even have to leave her own house. There wasn’t even a mythic journey. An anti-myth. This story is anti everything, as we’re about to see.

ANAGNORISIS

Mansfield gave her characters a very specific kind of epiphany. Some of them are outright ‘anti-epiphanies’, for example when Leila of “Her First Ball” actively chooses not to contemplate the passing of time and the prospect of becoming a matronly old woman.

Then there are what we might call ‘half-epiphanies’. In these stories, characters are not actively turning away from unwelcome reality. Instead, they would kind of like to know what revelation story-events are leading them towards, but they can’t quite grasp it.

Is there any epiphany in “The Canary”?

Here’s the ending:

… All the same, without being morbid, or giving way to – to memories and so on, I must confess that there does seem to me something sad in life. It is hard to say what it is. I don’t mean the sorrow that we all know, like illness and poverty and death. No, it is something different. It is there, deep down, deep down, part of one, like one’s breathing. However hard I work and tire myself I have only to stop to know it is there, waiting. I often wonder if everybody feels the same. One can never know. But isn’t it extraordinary that under his sweet, joyful little singing it was just this – sadness? – Ah, what is it? – that I heard.

“The Canary”

Mansfield wrote of this ineffable ‘something’ in other stories as well. Stand out examples:

- “Miss Brill“: The main character (Miss Brill) hears something crying when after she puts her fur into its box.

- “The Escape“: ‘Something’ stirs in the breast of the man when he hears the sound of a woman’s voice.

In the half-epiphany (or sublimated epiphany) there’s a ‘perception’ of, say, a voice which isn’t really there. By giving us half of the revelation, Mansfield is requiring the reader to work for it. The landlady of this story had a lover literally delivered to her door, but we readers are not getting any nut-shelled epiphany delivered to us. Hell no. We can get stuffed.

I experience this sublimated/nascent/half epiphany most strongly at the end of “The Garden Party“. I desperately want to know what Laura is feeling, what she has understood. Of course, Mansfield doesn’t tell us. We’re required to craft part of the revelation ourselves. And every reader will bring something different to a story anyhow, in line with the ideology of Modernist writers, who believed there was no such thing as The Truth, just versions of it, depending on viewpoint.

NEW SITUATION

The bird dies. Of course it does, how else could this anti- story end?

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

“I shall never have another bird.” Not until ‘the Chinaman’ arrives with another pretty feathered thing, I suspect. Or maybe next time it’ll be a kitten.

RESONANCE

Australia has a population of 27 million. Since the pandemic, we now have a million more dogs in this country, which means significantly more households with dogs than before. I’ve definitely noticed more dogs around our neighbourhood. Clearly, people bought pets as companions for the pandemic, perhaps because they were feeling lonely, or because they now had more time to spend at home to care for a puppy.

We are now seeing articles such as this one: Why ‘pet parents’ could be doing more harm than good, according to animal behaviouralists. Many of us would rather stay at home with our dogs than get back out there and socialise with fellow humans.

So yeah, Mansfield’s Canary story has resonance.

RELATED

One of my favourite contemporary bird artists is Cori Lee Marvin, Canadian Watercolour painter. Her paintings are full of humour. (And not just birds.)

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

CARSON MCCULLERS

Most of the latent love relationships in McCullers’s short fiction never reach maturity, and for good reason. As her narrator expressed it in The Ballad of the Sad Café (and evident, as well, throughout her writings), “The value and quality of any love is determined solely by the lover himself,” and such myopic vision by very nature destines one’s love to go unnoticed or bitterly unrequited.

To McCullers, a lover was always vulnerable unless he loved someone — or some thing — from whom he expected nothing in return. In “A Tree. A Rock. A Cloud,” a beery tramp confides to a pink-eared newspaper boy, a stranger to him, his “science of love,” which he conceived after being abandoned by his wife. The tramp’s sterile formula has led him to love things that cannot love back–first, a goldfish, then a tree, a rock, a cloud. But he invites the catcalls of mill workers in the all-night café in which he accosts the child and tells him: “Son! Hey Son!… I love you”. Despite his declaration, the tramp knows that he can walk out alone into the predawn silence and never see his so-called “beloved” again. Loving a woman is the “last step” to his science, he tells the boy. “I go cautious. And I am not quite ready yet”. The reader feels intuitively that the dissolute tramp will never be ready for the final step. He will not risk vulnerability to eros.

Understanding Carson McCullers by Virginia Spencer Carr (1990)