This is a wonderfully frustrating story. The awful character of Gilles will probably remind you of someone you have known at least once in your life. He is a caricature, to be sure, but not so much of one that he isn’t immediately recognisable. You will feel as if you are stuck inside a car with him yourself. Once you arrive at the house in Burgundy, you’ll feel like an unwelcome guest. You’ll be ignored by a Madame and finally, perhaps, feel a little lighter after someone gets told the truth. But you’ll feel, overall, that you’ve just returned from a very unpleasant trip.

PLOT

Part One

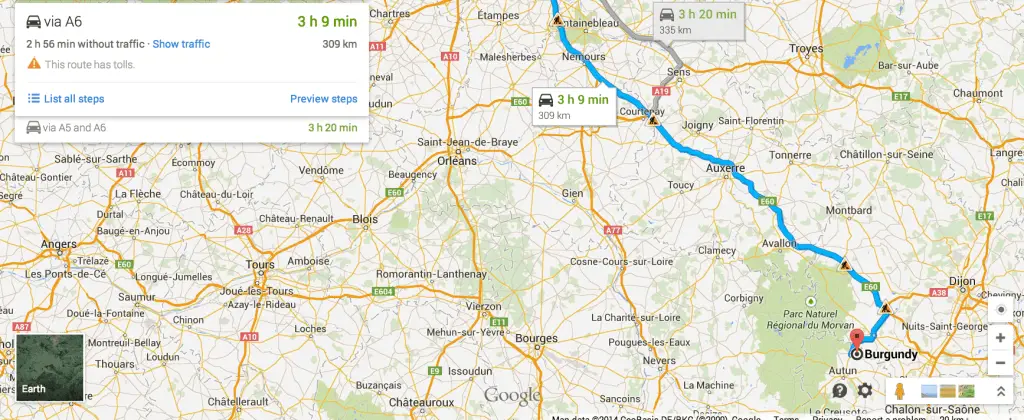

Lucie and Jerome Girard are due to meet an elderly woman for lunch in Burgundy. They are in France on holiday. Lucie, who tends to think the best of people, should have known better than to ask her insufferable boast of a cousin, Gilles, to pick them up from their cheap hotel in Paris and drive them to Burgundy. He is seven hours late and boasts about himself and his family all the way to Burgundy, despite it being obvious that his life isn’t nearly as excellent as he tells it. (He needs to borrow money for fuel, for example.) The house in Burgundy is unlike any other they have seen. Although they were too late for lunch anyway, it turns out their elderly hostess has had to go to Paris, and would’ve missed them no matter what. Since Lucie didn’t pass on the name of their exact hotel, she’s been unable to send her own apologies. Her granddaughter is barefoot and cold of manner; a bohemian type. Gilles takes off, leaving Lucie and Jerome there. He’s due to be at some conference in Dijon.

Part Two

Lucie is charged with the unpleasant task of making small talk with Nadine.

Small talk is a constructive safety device. If you pay attention, small talk progresses through a number of phases, and they’re all important and all build on each other. When you say “I wanna skip the small talk,” you mean “I want intimacy but I don’t want to work for it.”

@thefourthvine

Eventually, after dinner (of which Lucie hasn’t enough), Jerome finally starts to warm to Nadine, and then Lucie is grateful that the two are laughing with each other. The reader now has access to the backstory of how they happen to be at this house: The old woman seems to have a crush on Jerome, having met him in his youth. She has been corresponding with him for 20 years, after he was invited to her house for a political meeting many years ago. They are socialists. In bed that night, Jerome paces around the room tearing up papers. Lucie trusts that he’d never do anything truly destructive, but given Lucie’s set-up as naive and forgiving, this scene lends a sense of foreboding for the reader. What is Jerome about to do?

Part Three

In the morning Jerome gets up earlier than Lucie. Lucie wants to believe he’s being quiet so as not to wake her. She eventually joins the rest of the household. The housekeeper is getting rid of a rat with a broom. It is clear from the conversation now that Nadine and Jerome have developed a bond, probably the previous evening. Jerome goes out with Nadine to the local village, leaving Lucie at home for the entire morning to ‘play’ Scrabble on her own. Nadine asks Jerome to kiss her. Upon returning to the house, Nadine says that she must drive to the train station to pick up the grandmother, who is due in after one. Lucie sees strain between the two characters, and wonders if they’ve had a fight.

Part Four

It turns out Nadine has taken both Lucie and Jerome to the train station with her — Lucie has expressed interest in seeing what a French train station looks like. Nadine abandons them as soon as they arrive — she has her own errand to run for an hour or so. She says it’s to get a key cut, but Lucie doesn’t believe the story, especially given that it’s a Sunday, when a locksmith would not be working. The grandmother arrives, and ignores Lucie. When she asks Jerome how he is, Lucie answers for him, out of habit, but she is completely ignored. The reader is left wondering if she really said anything out loud at all. She is ignored in the same way she was ignored in the car with the insufferable cousin on the journey from Paris.

Part Five

It is now Monday and Gilles has arrived to pick the couple up and drop them off back in Paris. Gilles is full of talk about the food he’d been served in Dijon. He wonders why he’s so interested in food and Jerome starts off on a ranty monologue about how it’s because he’s really a lonely bachelor. Deflecting and ignoring, Gilles tells the dog to shut up. He asks Lucie if Jerome is all right. Lucie replies that yes, he is fine, and his speaking like that only proved it.

SETTING

Paris, on a Saturday in June. Next Burgundy.

Apart from being the name of a French town, the name of ‘Burgundy’ has associations with opulence and riches. Yet the house in Burgundy is not like that at all. The niece is ‘barefoot’. The elderly house servant Marcelle is too old to be working and she wears a white moustache. They eat in front of the television. There is not enough to eat. This story is all about money.

A sense of colour and brightness comes from the house in Burgundy. Outside, everything is white and searing and bright. Inside, the curtains are red; Nadine eats a (red) strawberry tart. The curtains in the guest bedroom are white. This is a scene full of reds and whites. Yet Gilles’ BMW is blue. Red, white and blue. (These are the colours of the French flag. Is it significant?)

Blue and red are the traditional colours of Paris, used on the city’s coat of arms. Blue is identified with Saint Martin, red with Saint Denis.

Wikipedia

CHARACTER

The reader is set up to identify and empathise most with Lucie. She is surrounded by unpleasant characters and deals with them admirably. We are told in narratorial asides that whenever Lucie happens to ‘answer back’, she means no malice. When she is dished out an insult she assumes nothing bad is meant by it. We all have the experience of such people, and are bound to admire Lucie’s responses. At the same time, we may be slightly frustrated regarding her naivety.

Gilles

In youth Gilles had looked like Julius Caesar, but now that he had grown thickly into his forties, he reminded people of Mussolini.

Originally from Quebec, Canada. Spends 10 months of the year in America. Says he has a huge research grant. Is currently based in France, in Neuilly. Keeps an apartment in Paris for ‘the girls’ education’ because he wants them to be fluent in French. Has another apartment in New Haven built in 1728. He lives there by himself, seeing his family only sometimes.

Has at three daughters. Wife is called Laure, who sounds as self-important as he is. Their daughter Sophie has an IQ of 180. Another Chantal has an IQ of 175. Chantal’s IQ is between 175 and 180. The girls’ mother ‘was a Soplex of the Soplex mineral water family’. Although he constantly boasts about being rich, he never has the change for anything, expecting others to pay. Supports ‘five people and a dog’. (Who is the unmentioned one?) He admires his wife for her well-off, delicate upbringing, and prides himself on the fact that his wife doesn’t enjoy sex with him. (The reader may well conclude that’s because he’s a selfish lover, but he frames it as though his wife is simply delicate.) The wife suffers from a skin condition (vitiligo?).

Full of self-importance, keeping Jerome and Lucie waiting for seven hours at their grimy hotel in Paris. Only agrees to pick up his cousins because he has to be in Dijon and wants company for the road. He is going to Dijon for an antiquarians’ trade fair, as the guest of a famous professor somebody, ‘a celebrated authority on medieval church carvings’. He calls himself one of the top three or four in his field. An expert in dermatology.

Wears a tweed cap and 1910 goggles. His blue BMW stinks of cigars. Has a slavering black Labrador sitting where Lucie is meant to sit. His radio is tuned on to a concert.

It is clear from the way Mavis Gallant writes the dialogue, full of non sequiturs, that Gilles isn’t paying the slightest attention to what Lucie has to say, continuing with his own thoughts as if she’d said nothing at all.

Jérôme Girard (late 30s)

Lucie’s husband. There are hints early in the story that all is not right with Jerome. Lucie notes that he is all right on this day. She asks him not to drop sad remarks this weekend. Does he suffer from depression? After Lucie asks him this he won’t speak to her. This sets him up as the antithesis of Gilles, who won’t shut up. He is at least 39, by Gilles’ estimations. Jerome doesn’t speak English. In the 1950s he has taken his university degrees in literature in France. Gilles assumes he did this because he wanted to write something, which is not the case at all. Come from money but is so irresponsible with it that he squandered it all on a series of failed ventures, like the backing of a string quartet who’d run out of the money and been stranded. In his youth, Jerome was a daily communicant (which means he received Holy Communion every day). If he missed Mass he went to Vespers. (Vespers is the evening version of Mass.) He never had enough to eat, but came into the money after his grandfather died. Then he started meeting a different sort of person. That’s when he’d met Madame Arrieu. At a political meeting, where the two had a meeting of minds over the idea of a ‘Negro King’.

Lucie Girard (28)

Cousin of Gilles. Last saw Gilles when she was about 12. She is a nurse who had taken six months’ special training in the psychiatric wing of an American hospital, so speaks some English. (We wonder: Did she meet Jerome when he was a patient there? Sure enough, several sentences later we learn that this is the case.) So devout and solemn as a child that her sisters feared she might become a nun. No longer a practising Catholic as an adult. Although her husband is incompetent re life, she does not want to strip him of his manhood, and render him incapable. Lucie is a peacemaker inclined to think the best of people, which explains how she ended up in Gilles’ company in the first place.

Lucie ‘had a special ear for him, as a person conscious of mice can detect the faintest rustling.’

‘Lucie sat alone at the Scrabble board putting together high-scoring words in the best places.’

Jerome thinks of her as a flower sometimes. Although Madame Arrieu is her husband’s friend, it is she who is tasked with the emotional labour of being good guests, even though it’s clear Nadine Besson doesn’t enjoy her company, finding her attempts to make conversation interminably boring. Lucie feels homesick for Montreal.’

Lucie’s dress is white, perhaps symbolising her innocence, her tendency to see the best in situations. This means she also matches the environment at the Burgundy house, with its white walls and curtains and bright white lawn under the sun.

Madame Henriette Arrieu

Lucie and Jerome are due at Madame Henriette’s house for lunch, but the delays of Gilles mean they can’t make it in time. Is not at the house anyhow because she has to be in Paris for some sort of memorial service to do with the Resistance. Spent the war in English. An anglophile. Attracted to Jerome. She’d been somehow involved with Jerome’s grandfather for a time.

Nadine Besson

The granddaughter of Madame Henriette. Has a French coldness in her manner. Handshake like ‘a newborn mouse’. A ‘Latin Quarter leftover’ by Gilles’ estimations. Cafe student type.

Marcelle the senior house servant

Although she doesn’t speak much in the story, Marcelle’s is a memorable image, especially as she has grown a moustache. Similarly, the housekeeper of One Morning In May (Doris) features large in the story even though the story is not about her as such. Marcelle smokes thin cigars. She has an assistant but lets the assistant play Patience. These two old ladies belong to the old world.

THEME

Time marches forward and there’s no going back.

Everything becomes defunct eventually.

Even if a couple doesn’t seem to like the other, or don’t really seem to get on, they can still be mirror images — one incomplete without the other.

We have the capacity to fool ourselves, but not the more astute of those around us.

TECHNIQUE OF NOTE

There are several mentions of mice, used figuratively. Lucie is attuned to her husband as one might be attuned to a mouse. Nadine Besson at the house offers Lucie her hand, which feels like a newborn white mouse. “A rat got in,” Nadine explains, with Marcelle holding a broom. Why the rodent imagery? Perhaps this is to do with the character of Nadine and her wish to attract Lucie’s husband away from her.

There is a wonderful juxtaposition between a life which revolves around insignificant things trumped up: Gilles is off to spend time with a professor the most obscure speciality one could think of. Jerome has squandered his money on a quartet and presumably other frivolities. This is set against a backdrop of political tension: There’s the socialist political leanings of Jerome and the old lady, reference to the Revolution. These characters are living in important times but individual lives are full of unimportant minutiae.

Though the story was written over 1970-71, the character of Nadine says:

“All you people, you intellectuals, are still living in the nineteen sixties.” Before then life had been nothing but legends: grandfather’s death as a hero, great-uncle’s deportation, grandmother in London being brave and bombed.

Against this recent backdrop, anything that happens at the beginning of the 1970s is bound to feel frivolous.

Below we have an example of two ordinary, everyday details bookending a matter of law which, at its heart, is about life and death:

The woman telling [the story] had on a felt hat. An unborn child was considered a legal heir if it had attained five months of its pre-natal life; but if a foetus was unlucky enough to lose a father when it was only four and three-quarter months old, then it came into the world without any inheritance whatever. It could no inherit its father’s land, his gold coins, his farm machinery, his livestock.

“What do you think of my washing machine?” said another woman, cutting off the story.

There is also a motif about doubling and duplication and mirror images running through the story.

Jerome and Nadine had dark eyes. It must be like looking at your own reflection on somebody’s sunglasses, she thought.

Nadine mimics Gilles after Jerome has repeated the conversation to her the previous night. Lucie feels both annoyed by and protective of Gilles at the same time.

‘… this conversation kept twisting and doubling back.’

the town with the wall and two towers

Jerome examines his own face in the glass ‘as if he’d forgotten what he was’, after the street has become too narrow for him and Lucie to walk side by side. ‘When they came to a corner they collided, each attempting to cross in a different direction.’

‘a miniature, eager Lucies was held on the surface of her glasses’

There had never been another Haydn.

The reflection imagery could be in regards to the old compared with the new, or it could be a comment on the relationship between Lucie and Jerome.

STORY SPECS

At approximately 12,000 words, this is more like a novella, broken into five parts.

This is the final story in the collection The Cost Of Living and was written after Mavis Gallant had published a couple of novels.

COMPARE WITH

Six Feet Under, the TV series written by Alan Ball is a great example of frequent, masterful juxtaposition. One moment the story will be about life and death; the next, Nate and David will be talking about paying the bills. David tells his mother he’s gay; Ruth says they’re having veal for dinner. Six Feet Under, also, is about the passage of time and the set design in particular blends the old and the new. The kitchen is timeless, but as soon as the characters set foot outside they are in ‘modern’ California (of the early 2000s).

WRITE YOUR OWN

Have you ever felt unwelcome while staying in someone else’s house?

Have you ever been trapped for an extended period of time with an insufferable person who seems a caricature of themselves?

Have you ever felt entirely ignored?