“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue by Poe Ballantine is included in The Best American Short Stories 1998. It kick started the author’s career, leading to a book contract. (Poe Ballantine is a great penname, don’t you think?)

Australia’s Richard Fidler interviewed Poe in 2014 when he was here in Australia for the Byron Writer’s Festival. Although this interview took place 16 years after “The Blue Devils” was published, I saw parallels between the author’s strong interest in ‘discovering what happened to his neighbour, local maths professor, Dr Steven Haataja’, who disappeared one night. Three months later, his burned remains were found tied to a tree in a forest. In Ballantine’s short story, published in the late 1990s, a fictional mother, likewise, develops a strong interest in a neighbourhood crime. She even finds her vocational calling because of it.

The bizarre thing is, Ballantine wrote his short story about a mother obsessed with a crime years before he himself became obsessed with a neighbourhood crime himself. Steven Haataja was murdered in 2006.

Be careful what you write, folks; fiction becomes your reality…?

The reason Poe Ballantine was interviewed in 2014? This is when his crime memoir about Dr Steven Haataja was published. It’s called Love and Terror on the Howling Plains of Nowhere, and is also a documentary.

SETTING OF THE BLUE DEVILS OF BLUE RIVER AVENUE

PERIOD

1963. The sixties were a time of great change in America (and elsewhere). Literary agents and publishers regularly tell writers to submit work set in the present unless there’s a good reason to set a story in the past. There’s good reason to set a story with these themes in the 1960s: This narrative is, to me, at least, all about how abusive people were using new notions of sexual freedom to justify their abusive actions.

The adult narrator overtly explains that Langton and Roland Sambeaux have a strange idea of what ‘freedom’ means, but in the context of stealing. It is up to the reader to apply this misunderstanding to Mr Sambeaux’s attitude towards children and sex.

Some feminists have pointed out that sexual ‘freedom’ for women often simply meant men’s free access to women’s (freshly birth-controlled) bodies, and that sexual access without true sexual liberation is oft-mistaken for ‘sexual freedom’. This short story is about how the relaxing sexual attitudes of the 1960s could be awful for children, as well.

I’ve heard it said that Australians are all about equality whereas Americans are all about freedom. (We might also say that of the broad difference between Democrats and Republicans; neither country is a monolith.)

A misplaced notion of the meaning of American ‘Freedom’ remains as relevant today as it ever was. Unfortunately for Australia, covid-19 restrictions across 2020-1 revealed how an increasing segment of the Australian population buy into misplaced notions of freedom. Commentators frequently blame this on the influence of America.

DURATION

“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue” begins when the narrator is eight years old, in 1963. After a detailed description of the neighbourhood we learn it’s 1966 (when the new Illinois family moves in next to The Miller’s.) This story covers the narrator’s middle childhood up to adolescence, then skips forward to adulthood in an epilogue-like paragraph at the end when the men are old enough to be married.

At several points across the narrative the time switches from iterative to singular.

One day [a new family arrives]

One winter morning [mother finds Bizzy on our front lawn]

These mark what we might call ‘turning points’ (though I’ve never found that marking out the ‘turning points’ of a story helps me to understand it better, or to write better myself, for that matter.

LOCATION

The author has travelled all over the United States but this particular story is set in San Diego.

Our first house, in the autumn of 1963, was a small, mustard-colored tract home in the older working-class suburbs of northeast San Diego.

Opening sentence

(I had to look up the meaning of tract home and now I can’t remember what Australasians would call them. Flats, I think.)

ARENA

The opening to this story mentions a particular house, and also zooms out to offer a panoramic view of the surrounding area. This is a camera with an active zoom lens.

Around the corner was a Jack-in-the-Box, where you could talk to the clown and get a hamburger for fifteen cents. They got rid of the clown eventually. For a while you could get deep-fried jumbo shrimp in tissue paper with fries; fried chicken, too, almond brown with miles of crust. It was years before I figured out the secret sauce on the hamburgers was Thousand Island Dressing. Behind the Jack-in-the-Box was a Thriftimart with a colossal red neon T that burned in the sky twenty-four hours a day. It was like a crucifix, a giant symbol of grocery-store truth flaming against the mountain.

The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue

The paragraph above achieves a number of storytelling functions aside from describing the scene for us:

- To me, especially, who isn’t familiar with the Jack-in-the-Box chain of restaurants, we are put in mind of a creepy retro children’s toy in which a ‘Jack’ springs out of a box once opened. This symbolism speaks to what I’ve heard called ‘Snail Under The Leaf‘, in which a geographical area (frequently the suburbs) seems safe at first glance, but check under a ‘leaf’ and you’ll find a slimy little snail. Over the course of this particular period in his life, the young narrator will learn things he was happier not knowing.

- Clowns are also inherently creepy, for reasons I go into here.

- ‘It was years before I learned…’ we are taught early on that this is an adult narrator looking back to when he was much younger. This tells the reader he’s had time to reflect, and we can expect a certain variety of truth: the truth which only comes after many years of reflection, and also a certain amount of forgetting.

- The detail he ‘learned’ much later concerns something wholly unimportant: A detail about hamburger sauce. This detail will juxtapose against the big and awful horror he discovers about the house down the road.

- Also, the detail of the Thousand Island Dressing clues us in on his socioeconomic status. (Food is good for that.)

- The large T on top of the Thriftimart will feel nostalgic to older Americans. To me, it only works at the thematic level, which Poe Ballantine spells out very clearly for us, teaching us how to read the story for theme. Like many, many stories, this one involves a narrator who uncovers a truth, and also links it to death (in this case, the Christian crucifix).

Now Ballantine’s narrative camera zooms in on a street of houses, and across the remainder of the story, the narrative camera will hop from one house to another.

The painting below is from the 1930s but Ballantine describes brightly coloured houses juxtaposed against some pretty dark goings-on inside the houses. The way the dark smoke emerges ominously from the chimney and the way shadow falls darkly across the main road of brightly painted shops, as well as those mountains in the distance, is the atmosphere I’m imagining when I read “The Blue Devils Of Blue River Avenue”.

MANMADE AND NATURAL SPACES

These houses are at the edge of civilisation, literally opposite a field of cows. This is the liminal part of town, where civilisation meets the metaphorical forest, where Hansel and Gretel lived in a cottage, where wolves can come out of the wilderness and terrorise the town.

There is also a metaphorical wasteland in this story:

Out behind our drab pink elementary school was a series of neglected arroyos and small canyons and brushy vacant lots where people would dump their junk: tires and mattresses and refrigerators and old cars. We’d wander down into these sunken other worlds, these Roman ruins of junk, and look around, sit behind the wheels of rusted cars, like on mattresses and watch the clouds sail over, catch scorpions and put them in jars.

“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue”

Note the use of the phrase ‘other world’ as if the kids have walked through a portal. When you live on the edge of town, you’re proximal to the imaginative portal, from the real world into a liminoid space (slightly different from liminal). Or perhaps we might call this cosy dumping ground a heterotopia.

Notice, too, that the paragraph opens with brief mention of the school. The school is your ultimate supervised arena when you’re a kid so pink school (the pink of it suggests baby girls and therefore a certain cosiness). So the ‘Roman ruins of junk’ are a carnivalesque arena where the boys are wholly without supervision, smoking and whatnot, claiming the space as theirs, practising a grotesque version of what they consider ‘adulthood’.

WEATHER CONDITIONS

Fog is a feature of San Diego. Technically these are marine layer clouds, which descend most often between May and August.

Mist and fog is, of course, highly symbolic when it rolls into a story. It often indicates lack of clarification, obfuscation, confusion, loneliness, that sort of thing. But in this story, Ballantine takes fog and turns it into a suburban monster zombie:

The mist did not lift for a long time. Some days it was so thick you couldn’t see the hands on your watch. It was clammy and smelled of mushrooms and bandages and Styrofoam cups. It spun and drifted with a lime tint on its edges, and did not stop at your eyes but trickled and pooled in creepy lagoons all the way down to the bottom of your brain.

“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue”

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

Why has the author chosen these particular houses to zoom in on and describe in detail? Well, the first person narrator (a child at the time, grown now) grew up in a lower-middle class household, with a father who moved up in the world when he became a schoolteacher. And then when his parents move him into this street, he is newly confronted with a household poorer and more chaotic than his own, as well as with a family with more money and more carefully run than his own.

A first person narrator whose own socio-economic status slots neatly between the extremes of the children who live on Blue River Avenue is a perfect choice when conveying to a reader the lottery of birth.

On the topic of lottery of birth, the short story opens with a snippet from a longer poem by William Blake.

Every Night and every Morn

“Auguries of Innocence“

Some to Misery are Born

Every Morn and every Night

Some are Born to sweet delight

Some are Born to sweet delight

Some are Born to Endless Night

From my own childhood book of nursery rhymes I recall a similar one:

Monday’s child is fair of face,

“Monday’s Child”

Tuesday’s child is full of grace.

Wednesday’s child is full of woe,

Thursday’s child has far to go.

Friday’s child is loving and giving,

Saturday’s child works hard for a living.

And the child born on the Sabbath day

Is bonny and blithe, good and gay.

Believing the rhyme portentous if it appeared in a book, I asked my mother which day of the week was mine. I was born on at six a.m. on a Thursday, she told me. Good. Hang on, what does it mean, ‘has far to go’? Does this mean I’d be gallivanting around the world having a grand old time, or did it mean my life goals would be achieved only after a long struggle? Then I realised something worse: The nursery rhymes had been published in England, yet I’d been born in New Zealand… six in the morning. This meant I was actually born on a Wednesday, European time. HAD THEY TAKEN TIME ZONES INTO ACCOUNT?!*

(*Yes. My life has not been full of woe.)

“Monday’s Child” is a horrible rhyme, but what if we don’t take it literally? What if it’s simply a statement about fate and fortune?

Stories which place rich and poor people together in the same arena function as a natural source of conflict for storytellers. Fortune and ill-fortune is a broader phrase, and better describes the children living on Blue River Avenue.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE

This describes the land which lives inside the main character. The imaginative landscape, the difference between what is real in the veridical world of the story and how a character perceives it — never exactly as it is, but rather influenced by their own preconceptions, biases, desires and personal histories.

The main character is an older man looking back on his childhood with the benefit of reflection. If he were writing this story as an even older man, he might hypothetically come up with a different take on things again. At the time, as a boy, he has a simplistic view of rich versus poor kids, and his main goal is to garner social capital among peers. With the benefit of hindsight, he can see why his mother was guiding him away from the most problematic house on the street.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

THE NARRATOR’S FAMILY

Ironically, the father has secured a job which brings him into the social middle class (if not the economic one — he is a teacher), yet this elevation is the precise change which immerses the eight-year-old narrator in an underbelly of violence and sex abuse.

In contrast to the Sambeauxs, the Carrs and the Millers, the narrator has a mother who looks out for him, and he knows it. However, his interpretation of her vigilance is perceived as unnecessary panic by the eight-year-old:

My mother cut sharp glances at me. She had the kind of vision that went right through you and saw into your future. She saw me taking LSD, or driving drunk off a cliff, or marrying a Filipino go-go dancer with a long scar across her abdomen. She saw weeds coming up in the garden of my innocence, and wormy, wild apples waving in the wind.

“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue”

In a later paragraph, when the boys are about to summon ‘sisters’, the eight-year-old narrator knows something is icky and he is very glad to hear his mother calling for him to come home. He can’t escape the situation of his own volition without losing social capital with the other boys.

The short story shifts from iterative to singular with the words ‘One day…’

One day, my mother told me I couldn’t go to the Sambeaux house anymore. She thought Mr. Sambeaux was a bad man.

“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue”

THE SAMBEAUX FAMILY

When storytellers describe a house, they are symbolically describing the people who live inside it, but we don’t know until second reading which detail is symbolically significant (a ‘telling’ or ‘off-duty detail) and which is descriptive (‘off-duty detail’). But even on first reading, the ominous, noir atmosphere is unambiguous.

There was something mysterious and menacing about that house: a blood-curdling scream, a silhouette of a knife in the window, a wolf on its hind legs with a leather tail scuffling along behind the juniper trees. Out front were statues of undressed women holding up grapes or baskets and showing their armpits. A cactus garden grew against the living room window: prickly pear, barrel, agave. Handmade birdhouses swung from the branches of a big yellow poplar.

“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue”

Note, however, how Ballantine closes the paragraph with a juxtaposing cosy detail — handmade birdhouses hanging from a big yellow poplar — the exact sort of scene we might see in a children’s picture book.

Ostensibly because Mr Sambeaux is an upholsterer, the inside of the house feels like a bordello, with emphasis on the complementary colours of reds and greens.

Juxtaposition is key throughout the story — namely, childlike naivety juxtaposed against sexual precociousness — and even the description of colour are working toward this end.

Ballantine describes the venus fly trap as ‘an obscene birth sequence in reverse’, an observation which achieves two symbolic functions at once: Juxtaposition of birth vs death, and a grim linkage between youth and maturity.

Note that descriptions of the Sambeaux house are dip fed to us across the story, each of them a description of imagination as much as reality. Here’s how the narrator sees the house once Homer arrives to the neighbourhood:

From a distance, the Sambeaux house must have appeared to him to be the place to make friends. There were children everywhere: peeping from windows, lounging against cars, hanging lemurlike from trees, barelegged, barefoot, the spirit of Peter Pan and Tobacco Road. There were paper clouds above the Sambeaux roof, pink pastel streaks painted across the sky, devils on the rooftop, monkeys on wires. A big cardboard vulture squealed over. Homer knocked on the door. Roland and Langston ushered him in.

“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue”

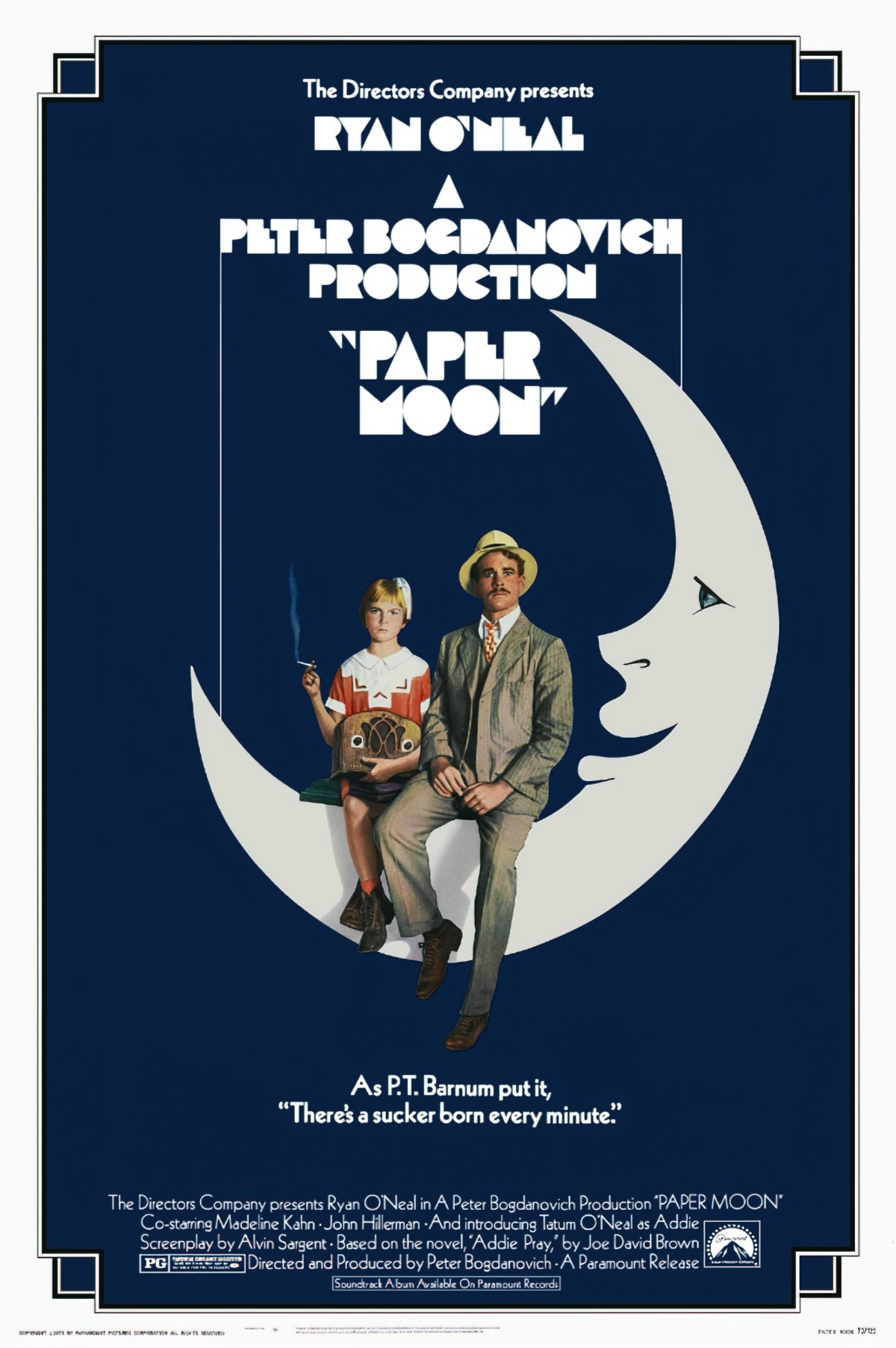

I find the metaphor of papercraft to describe the Sambeaux house really interesting. It reminds me of the 1973 film Paper Moon, also about a smart, precocious, neglected child who is drawn into the underworld of crime and sex by her own father.

What does the ‘paper’ of Paper Moon refer to?

Peter Bogdanovich also decided to change the name of the film from Addie Pray. While selecting music for the film, he heard the song “It’s Only a Paper Moon” (by Billy Rose, Yip Harburg, and Harold Arlen). Seeking advice from his close friend and mentor Orson Welles, Bogdanovich listed Paper Moon as a possible alternative. Welles responded: “That title is so good, you shouldn’t even make the picture, you should just release the title!”

Wikipedia

The song has been covered many times since.

The paper moon and canvas sky of the song refer to a one-sided love which can’t be real until the object of the singer’s affection is reciprocated.

The pastel which paints the sky and the cardboard vulture of Poe Ballantine’s short story also suggest that someone is not ‘real’, in this case: the fun and games. The detail of children swinging like lemurs from the trees transfer the danger of a symbolic jungle to the edges of the suburbs: There’s no real community here. It’s every kid for themself.

MR SAMBEAUX

An upholsterer whose up-and-down needle has clear phallic symbolism. When he’s done with his Playboy magazines he gives them to his ten- and eight-year-old sons.

He is rarely seen by the narrator but memories are mainly of him drinking from a tumbler or going to the liquor store. In the thumbnail description of this alcoholic father, more is made of that red letter T atop the Thriftimart store — his face shines as red as that in the night. This is brilliant because it emulates the way we (especially as children, perhaps) tend to fixate upon two different things and by the time we are adults, our minds have fixed them together as a conjoined unit in our memory.

MRS SAMBEAUX

The mother isn’t mentioned for a good while, and then when she is, we are told she has gone somewhere with Mr Sambeaux.

Langston Sambeaux

Older brother of Roland. At twelve, already going bald. A rough, physical bully to the younger boys. He insists that the narrator call him ‘Uncle’.

Roland Sambeaux

‘Skinny and dark with a little cap of oily brown hair’. Same age as narrator (eight). ‘Eyes like crystal balls filled with olive oil, and his face was lean and wrinkled in a fine, cracked way, like brown eggshell.’ Regularly shows up with injuries (black eye, broken arm). He always has a reason such as falling off his bike.

The narrator mentions he once accidentally hit Roland with his baseball bat and gave him concussion. This early detail becomes symbolically circular later on, in the closing paragraph.

Both Langston and Roland are thieves who steal from the immigrant man who runs the ‘End Store’.

YOUNGER Stepbrother TO LANGSTON AND ROLAND

Mentioned but not described

Step-sister 1

The sisters all had skinny legs and big, yearning eyes, like stained glass windows in French cathedrals.

“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue”

Seven-year-old Bizzy is the eldest and (already) deemed the prettiest by the boys. Langston sexually objectifies her in an incestuous way, and asks the narrator if he ‘wants’ Bizzy.

Step-sister 2

The younger step-sisters are not individuated because the boys don’t see them as human beings, rather as their playthings. Their eyes are like a literal object (stained glass) but stained glass is the sort of thing you find in a place of worship. These girls should be revered, but they are very much not. (This double-duty is what makes the description of ‘stained glass windows’ so masterful.)

Step-sister 3

Since the eldest step-sister is only seven, the youngest must be very young.

THE CARRS

The Carrs lived next door to us in a falling-down purple house. There were five kids in that house.

“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue”

MR CARR

A ‘giant with leukemia’.

MRS CARR

The mother died two years earlier which, in combination with the father’s poor health, explains how the Carr children are so poorly supervised, as the Sambeaux children are, for different reasons.

OLDEST SON

Will soon ‘go to Vietnam and lose his mind’

WHITEY

A year older than the narrator. He is nine years old and smokes Lucky Strikes. He’s called Whitey because he has long, straggly white hair and lips which turn blue.

This is another boy who likes to beat the narrator up with his ‘hard little fists’.

This casual childhood violence is typical of the era. It was expected that boys jostle for position on the masculine hierarchy by physically assaulting each other. ‘Rough and tumble’ was expected (and encouraged) by the adults. I was a child of the 80s so missed this era, but that old attitude was still manifest when I was growing up. I had a few near-retirement teachers who subscribed to it. Writing this story in the late 1990s, Poe Ballantine is also making a comment on the casual violence of the 1960s when he includes the almost comical detail about Whitey needing to borrow the narrator’s asthma inhaler after beating him up.

QUEENIE CARR

The youngest child, but described first by the narrator. ‘A dumpling runt who would change into a glittering sex princess in high school’.

But near the end of the story we learn the reality of what this means:

They stood out under the threatening sky like lightning rods for adulthood. Queenie Carr, ten years old, already had green eyelids and a slinky walk and a bleary lipstick grin and her purse. She would sidle up to me and dabble her fingers along my ribs. Meet me later, big boy, she’d say, ten o’clock, out by the gas meter.

“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue”

THE MILLERS

The Millers had a pin-up calendar in their garage — you peeled up the cellophane and the girl’s bathing suit came with it.

“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue”

MR MILLER

Doesn’t live at the family home. Drives the ferryboat to Colorado.

MRS MILLER

A barmaid

Snooks

A girl who joins Whitey and the narrator at the wasteland and plays grown-ups. She smokes and tries to mask the odour by smearing green toothpaste on her tongue. Uses sexually precocious language which the eight-year-old narrator doesn’t understand at the time.

FUBSY

Younger brother of Snooks, eight years old like the narrator. Pudgy. Like his older sister Snooks, he thinks that knowledge of sex makes him a grown-up and gives him social capital. He therefore tells the narrator that he has had sex with their fifteen-year-old babysitter. The narrator doesn’t believe him.

This is ironic foreshadowing: What the kids talk about isn’t happening. What the kids aren’t talking about is what’s happening. Note that later in the story, with the reveal of sex abuse, we are not given any details at all, emulating the culture of silence around abuse in this small community.

This says something more generally about 1960s America: notionally liberated, but with a dangerous admixture of taboo and secrecy and shame. The end of the 1960s were quite different from the early 1960s (in this case 1963). The TV series Mad Men explored that in detail, with old-school Don Draper only catching up with the rapidly changing culture in the final few episodes.

THE ROSES

One of the ‘good’ families as designated by the narrator’s mother, with a symbolically appropriate name. (These days I also think of the characters of Schitt’s Creek.)

THE BENDONELLIS

Another family designated as a ‘good family’. These families are not fleshed out, but included to show us that this is a realistic sort of neighbourhood, that although the narrator has been drawn into the underworld of neglected children, many other children are well cared for. This describes every community everywhere. The neglected are invisible to the privileged — invisibilised, in fact, because although the narrator’s mother is keen to look after her own son, she does absolutely nothing to help the children who she must know are being abused.

Inclusion of ‘Good Families’ describes the culture of silence about child abuse. Note that mandatory reporting didn’t happen in America until the mid seventies. The eras before that were dangerous for children, and perhaps the 1960s were more dangerous than the decades which came before precisely because of the more relaxed attitude towards ‘freedom’ and sexuality.

THE ASHMONTS

At Christmastime 1966, the Ashmonts, a navy family from Illinois, moved in next door to the Millers. The Ashmonts looked like Illinois people to me: all big teeth and dimples.

“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue”

HOMER ASHMONT

The oldest Ashmont child. He makes his way to the Sambeaux house, wearing his baseball cap cockeyed, but it’s clear from the narrator’s description that he is the archetype of an All AmericanTM sporty kid, whose natural physicality alone will afford him plenty of social capital among his peers.

We can deduce that if he didn’t come from a very caring family he might also have been drawn into the underworld of the Sambeauxs. This short story has a fatalistic streak, meaning that any one of us would’ve turned out like the Sambeauxs had we been born a Sambeaux.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE BLUE DEVILS OF BLUE RIVER AVENUE”

PARATEXT

THE TITLE

I went for a bit of an explore of San Diego on Google Maps and failed to locate where this story might’ve been set. I conclude it’s wholly fictional, as there was no Thriftimart in the northeastern part of San Diego.

Nor could I locate anywhere with a sparkling blue river which might’ve inspired the naming of this (fictional) avenue. There are a number of San Diego street names with either ‘blue’ or ‘river’ in them, but San Diego is more of an ochre landscape with dots of colour: the citrus fruit growing on trees, the jacarandas. The blue of the’ avenue’ (a fancy name for a street, usually with tall trees growing along it) must’ve been named for the aspiration of lush vegetation and life. This story is an ironic inversion of lush and natural. Even the children are described as elderly.

Since I’ve already said quite a bit about the colour symbolism of this story, it’s worth pointing out that ‘blue’ is a synonym for ‘inappropriately sexual’. The importance of colour starts with the title. And like many short stories, this title reads differently to first time readers. The double meaning of ‘blue’ becomes evident only afterwards.

Near the end of the story we also learn that ‘blue devil’ refers to the recreational drugs that came to town as ‘anaesthesia’ due to the Vietnam War. They were marketed at kids, and the ‘unwilling child plaintiffs’ of Blue Avenue were their perfect customers.

SHORTCOMING

Child narrators in stories all share the following: They are naïve to the ways of the world. (And if they’re not, they’re terribly damaged.) So often in stories, something big happens which propels the child towards adulthood, from a prelapsarian to a postlapsarian state.

Because the eight-year-old narrator doesn’t understand how bad other houses can be, he is drawn towards the worst house on the street, which in one terrible way, is full of life. He doesn’t believe his mother when she says Mr Sambeaux is a ‘bad man’. He thinks in a binary, black and white way about ‘good’ and ‘bad’ people. Ergo, if he has seen Mr Sambeaux laughing and occasionally being Not Bad, then he must be good, actually. At eight years of age, he mistakes grooming and bribery and bad parenting for privilege.

DESIRE

The narrator has conflicted desires. He craves the excitement and fun offered by the most neglected kids on the street. He needs their approval. He is also scared of them, and senses an icky underworld which he could easily be drawn into… without his mother’s intervention.

OPPONENT

For storytelling purposes, the mother is part of the opposition because she stands in the way of the narrator getting what he wants (or what he thinks he wants).

I didn’t doubt my mother’s wisdom, but she was beginning to make my life difficult.

“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue”

But the Minotaur Opponent, the one who creates immense chaos across the small community, not just in the household, is Mr Sambeaux, and the boys who learn violence from him. In this way, he functions as a horror villain. His bordello-inspired house is his lair and his workshop is symbolic Hell.

This story extends even more widely than that. Mr Sambeaux is himself a product of the 1960s and, as I described above, a misplaced notion of American freedom, which he applies in a sexual way to his own children, because it suits him. ‘Society’ is part of the problem here. (We know nothing of the mother; she is ‘killed off’, not literally, but via invisibility.)

PLAN

The narrator as newcomer is swept along with plans made by the unsupervised children who act parts in a pre-existing stage play of their own making. They steal from the shop, hang out at the local dumping ground, beat each other up, read porno magazines…

The narrator is pulled away at this point by his mother and we are left to infer what the other boys get up to in his absence.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

This story needs to cover at least three years because that’s how long it takes for the narrator to progress from a child to an adolescent, in which peer approval is the most important thing.

Terrible things are happening behind the scenes, outside the narrator’s field of view. The camera remains tight on the child narrator, but the adult (extradiegetic) narrator fills in extra details for us, leaving enough room for readers to fill in the gaps ourselves. This allows readers to participate actively in building the narrative and makes for a more interesting story. That’s the Doylist reason for leaving gaps in the story.

The Watsonian reason: These are difficult things to talk about and a decent, well-bred man doesn’t put them into words.

The thematic reason: There remains a culture of silence around incest.

Therefore, the battle here, on the page, is mostly internal. For the child narrator, this is a battle between fun and safety, between family and community, and the unease which comes from a gradual understanding of privilege and neglect.

ANAGNORISIS

Things change for the better (for the narrator) after the assault of the girl. He is no longer the only boy in the neighbourhood barred from spending time at the Sambeaux house. So he makes friends with Homer who takes him home to eat pink stroganoff. (Notice again the colour pink, the baby girl colour, the safe colour.) Now the narrator has a friend of his own socioeconomic class, someone his mother approves of. They can now go everywhere together: to the pool, to the beach. They have fabulous teenage years.

While at Homer’s house the narrator understands what a good house really feels like. Although the narrator is not poor, Homer’s house is a level of privilege above his own, with the delicious food, the colour TV, and the many sporty, healthy kids with the great genes.

This is how people are supposed to be! I thought.

“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue”

The narrator’s pre-adolescent self is partway there but doesn’t quite have the words to describe what he’s feeling: safe. This is how children are supposed to be. Well-fed, talking about baseball, playing boardgames.

But his older self knows he was only ‘vaguely’ aware of happenings outside this cosy life he strikes up with Homer. His adolescent self knows little of the Vietnam War and also very little about the court case which, we deduce, involves Mr Sambeaux, or perhaps the oldest boy, who must be 17 or 18 by this point.

Meanwhile, the narrator’s mother is having her own self-revelation: After being called as principal witness in the 1967 court case she realises she enjoys court and finds a career in it.

NEW SITUATION

The Carrs and the Sambeaux kids become addicted to drugs. We can now put two and two together about Queenie. We know why she’s no longer a pudgy little kid; she’s turned into a ‘sex princess’ because she’s addicted to speed (and not eating food).

It is eventually confirmed that it is Mr Sambeaux on trial (rather than the son).

Regarding Mr Sambeaux, the fact that he works as an upholsterer is symbolically neat and tidy because he ‘covers things up for a living’ and manages to get a light sentence using the skill of covering up. (The jobs of parents are frequently useful for the plot in children’s stories as well.)

Roland does well enough to get married. The other neglected children aren’t mentioned.

The T of the Thriftimart Store isn’t mentioned again, either. This is slightly surprising because many writers would’ve chosen to refer back to it at the end, I think. But the T has done its job. The Truth has been revealed. To mention it again would be on the nose.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Everything in this story suggests the narrator and Homer do well while the Carrs and the Sambeaux children mostly do not.

RESONANCE

There’s a sign above the receptionist’s desk at our local doctor’s which reads “There but for the grace of God go I.” This short story says something similar. By taking a boy into various houses along the same street, we understand that he could have been born into any of these houses.

The difference between privilege and neglect (or poverty: neglect at a societal level) is a common theme for storytellers, and never gets old (unfortunately).

Katherine Mansfield did it in “The Doll’s House“, for instance. Mansfield’s story is a great introduction to the same theme but for adolescent readers because the symbolism is relatively obvious, and young readers are still in training to find the more complex symbolism in sophisticated lyrical short stories for adults.

“The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue” goes deeper than Mansfield’s. Ballantine explores the social phenomenon whereby we tend to find friends of people the same (or very similar) socioeconomic status to ourselves, because that’s where we feel the safest. This holds true even for children from horribly abusive families, which is how abused children find themselves in abusive adult relationships as well.