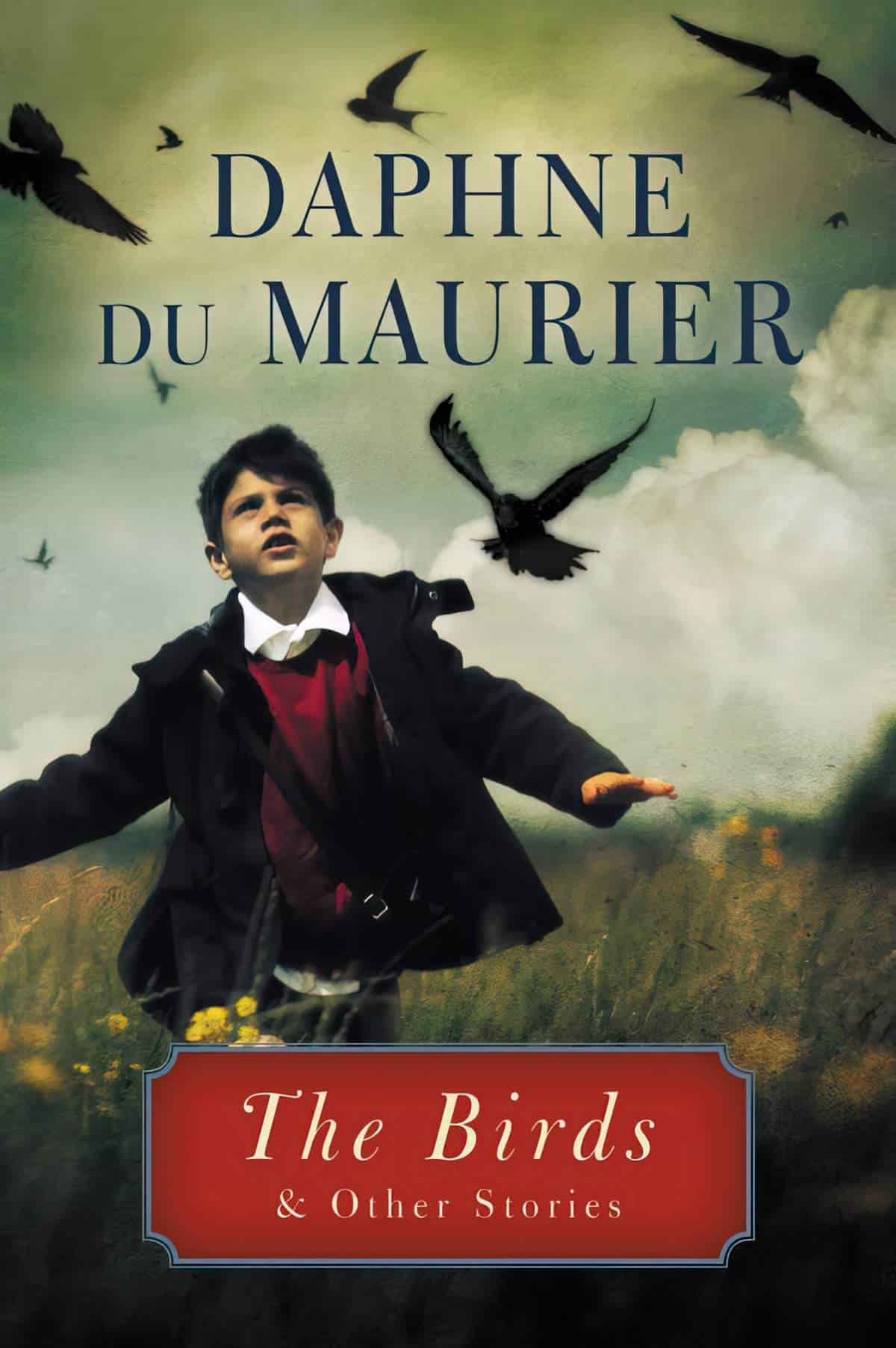

“The Birds” is a short story by British author Daphne du Maurier. Alongside Rebecca and Jamaica Inn, “The Birds” remains her best-known work. But that’s because of the Hitchcock film. Reading the short story, I learn the two versions are so different we should consider them two different narratives. In fact, du Maurier’s short story shares more in common with Stephen King’s The Mist than with its own film adaptation:

- A man lives near a body of water (in this cast the coast; in The Mist it’s a lake)

- He has a fractious relationship with another man who lives nearby

- He notices something strange happening out on the water but can’t quite make it out

- The supernatural thing comes from the water into the town, killing humans for no obvious reason other than that’s its nature

- The supernatural monster tries to penetrate man-made buildings, via the usual terrifying entry-points: doors and windows. (And also through chimneys in “The Birds”)

Sure enough, Stephen King has named Daphne du Maurier as an influence. “The Birds” is a straight-line influence on “The Mist”. Others see parallels between Rebecca and Bag of Bones.

With “Bag of Bones,” King reins in the gore and spins a pretty good yarn about a house named Sara Laughs that’s overrun with restless spirits. But, looking up at the early dawn after a night of page-turning, one realizes that Sara Laughs doesn’t haunt like “Rebecca’s” Manderley. The ugly small- town secret at the heart of King’s latest novel appeals primarily to the reader’s baser instincts for rubbernecking — hardly the denouement set up with jewel-like precision by du Maurier.

Gripping Grief / With a nod to du Maurier, Stephen King haunts a house and a wealthy widower, reviewed by Yunah Kim and Elizabeth Judd (1998)

Hitchcock’s 1963 film adaptation of “The Birds” is badly cast. The ages of the actors make no sense. 54-year old Lydia has a 33 year old son and a 14-year old daughter.

However, the film successfully put me off birds for a few months after watching. (Avoid during magpie season.)

Alfred Hitchcock adapted three of Daphne du Maurier’s work for film: Jamaica Inn (1939), Rebecca (1940) and The Birds (1963).

WHERE TO LISTEN TO DU MAURIER’S “THE BIRDS” SHORT STORY

WHAT HAPPENS IN THE FILM

A wealthy San Francisco socialite pursues a potential boyfriend to a small Northern California town that slowly takes a turn for the bizarre when birds of all kinds suddenly begin to attack people.

IMDb

The film centres around Tippi Hedren’s character. Resonant imagery: The school jungle gym with all those ominous black birds perched on it. Also Tippi Hedren’s glamorously falling-apart 1950s hair-do which, for some reason, isn’t covered in bird slops. Somehow she avoided that.

(Tippi Hedren is matriarch of an acting-celebrity family; notably, Melanie Griffith’s mother and Dakota Johnson’s grandmother.)

Both [du Maurier and Hitchcock] undercut the ostensibly conservative character of the popular romance by exploring dimensions of human perversity contained within it, not simply as a foil to dramatize the growth, development, and triumph of the heterosexual couple, but also as the primary source of fascination and allure. […] Hitchcock inhabited and was partly responsible for the triumph of American popular culture in Europe in the decades after World War II; du Maurier, on the other hand, though she showed an interest in film, despised that culture, and satirized an American takeover of Britain in her last novel Rule Britannia (1972). […]

In The Birds, Hitchcock undertakes a unique adaptation — a kind of adaptation in reverse — where he fills out the scenes schematically portrayed in du Maurier’s short story with a full-blown “family romance” narrative scripted by Evan Hunter in a way that makes explicit the manner in which du Maurier’s short story undermines the conventions of the romance narrative that both he and du Maurier inhabited for most of their careers.

Richard Allen, “Daphne du Maurier and Alfred Hitchcock”, A Companion to Literature and Film, 2004

WHAT HAPPENS IN DU MAURIER’S SHORT STORY

There’s no wealthy San Francisco socialite and no beautiful Hollywood star to play her. Just an introverted family man who lives on the coast in the South of England, 300 miles from London. Nat Hocken works part-time on a farm because of a disability acquired during the war. He does light farm work three days a week.

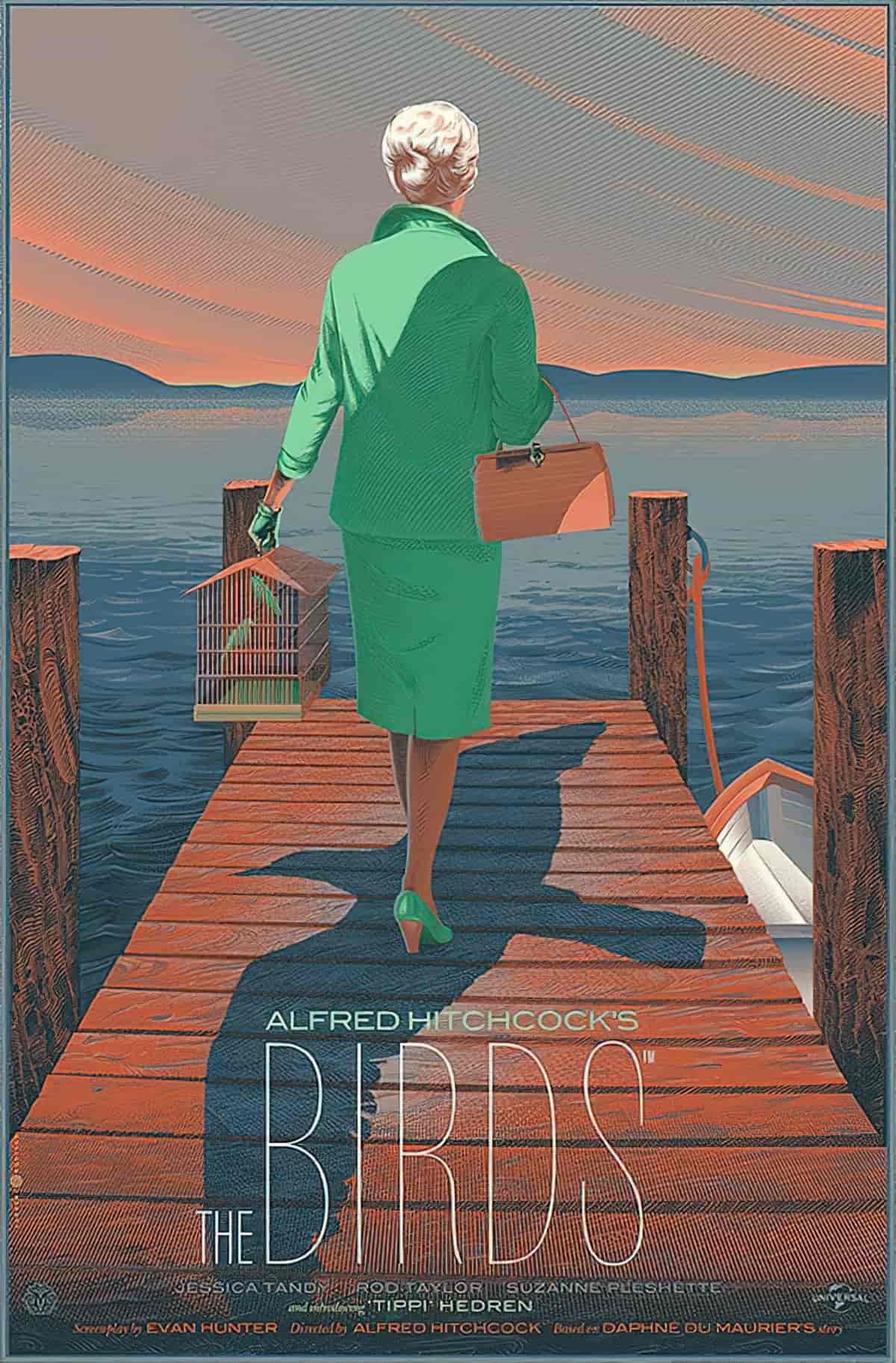

I’ve seen the Hitchcock film a handful of times so I find it difficult to get the Bodega Bay setting out of my head. The following paintings were made with the help of AI.

WHY IS NAT HOCKEN A GOOD VIEWPOINT CHARACTER?

Since he has returned from war, he is surely psychologically affected as well as physically affected. A returned vet would be hypervigilant and first to notice something strange in the skies.

Also, Nat is given light tasks and a part-time load. These things combine to make Nat the perfect viewpoint character to notice strange bird behaviour.

Nat is the first to notice when, one fine day in autumn, small hedgerow birds fly into his children’s bedroom and die. About fifty of them. He clears them up the next day.

SURROUNDED BY MINIMISERS

No one else in his social circle seems concerned about this event. Only him and his family. He boards up the windows. Like the story of Noah and his Ark, he’s taking precautions based on instinct. No one else prepares. Those who prepare will survive. We see this storyline in the Bible and also in Aesop’s fables. Makes sense. Without preparation, humanity wouldn’t have made it this far.

BIRDS AS OPPONENTS

These birds have no desires of their own. This makes them the classic Minotaur Opponent. Such opponents are like unthinking robots, hellbent on destruction. They won’t stop. They can’t be persuaded or convinced because they seem coded for destruction. We can’t identify with such evil at all.

We tend to find swarms of things terrifying, whether they’re rodents, insects, sci-fi inventions or birds. Even swarms of cats can overwhelm. Swarms, for humans, mean plague, whether viral or bacterial. Swarms mean crop destruction. Creatures which flock and swarm are individually harmless. But together they form the huge body of a monster. Even in swarms, creatures do not directly cause human death. Rats carry fleas which carry disease. Locusts deplete our food, but only become deadly when we have nothing else to eat.

In horror stories, writers sometimes cut out the middle-man. The creatures themselves cause death directly.

THE BIRDS INVADE

Birds stop chittering in the mornings. In modern times, we pay little attention to birdsong unless we have a special interest in birds (or live in regional Australia, where the bird calls aren’t exactly subtle). But historically, birds have provided an important cue around incoming threat. We’ve evolved alongside the animals around us. We’ve outsourced part of our sniffing brain to dogs, for instance. Companion dogs dedicate a huge part of their brains to the sense of smell, freeing our own brains up for ‘higher-level’ tasks. Likewise, birds have a much better sense of sight than we do, as well as an elevated vantage point. Birds are the first to detect threat. When birds leave the area, you can be sure something’s up. We may not pinpoint why, but an eerie silence in nature speaks to our long evolution alongside creatures we’ve come to rely on.

SILENCE AS HORROR

When adapted for film, unusually for its era, The Birds had no soundtrack, emphasising the silence described by Daphne du Maurier. Precisely because it was so unusual, silence in the film unsettled. The foley SFX of flapping wings horrified audiences. It is far more common now for horror and suspense films to utilise silence, avoiding the schmaltz of violins, which easily teeters into parody.

“THE BIRDS” AS ZOMBIE FLICK (FLAP)

Du Maurier’s birds are not one bit like real birds. In the beginning, they are described as ‘purposeful, intent’, and ‘caught up in some driving urge’. But they lose their purpose. Now they ‘fed as though they did so without hunger, without desire.’ Lack of desire is their downfall. Zombies in stories will always be flat (rather than fleshed out, ha) because of their lack of free will. Their desires are basic (not tiered). The birds can’t make plans. They are indistinguishable from one another, or from any number of other horror monster creations which simply won’t quit. They don’t understand the wretchedness of their condition.

Like zombies, they seem possessed by something, throwing themselves at the house, determined to get in, sacrificing their own lives to some greater, assumed cause. Nothing deters them. Yes, “The Birds” is a zombie story, and the zombies are birds.

The birds increase in number and also in size. Nat is glad he boarded up his house. Next he boards up all the chimneys, except for the one in the kitchen.

This bird attack makes the news. The family listens to the radio. It’s a national emergency. Perhaps even abroad, too. The radio starts to play dance music. This must have been disturbing for a readership who remembered living through wartime — when the radio defaults to dance music it means something terrible is happening. No one is available to keep their listeners in the loop. Centralised communication allows humans to form ‘swarms’ (armies) of our own, and when radio is down (or these days the Internet) you know something has really gone wrong. (As I read “The Birds” in 2022, Iran shut down mobile internet, WhatsApp, and Instagram.)

MAROONED — AN ISLAND STORY

Not an island, a peninsula. But the family may as well be on an island. No surprise, Robert Louis Stevenson (who wrote Treasure Island) and R.M. Ballantyne (who wrote The Coral Island) were strong influences on Daphne du Maurier (alongside the Bronte sisters).

Nat’s family runs out of supplies, as they were unable to collect groceries that week. So together they venture to the neighbours’ house, planning to ask them for food. The neighbours have not taken the bird situation seriously. When the Hockens reach the house, they discover the neighbours have been infiltrated by birds and killed. The Hocken family takes enough of the neighbours’ supplies to last them a while longer in isolation.

The family continue to take refuge inside their own dwelling. Birds continue ‘shelling’ their house.

DOES NAT’S FAMILY SURVIVE?

At the end of the story, there’s nothing to hint of an ending to the bird attack. Foreshadowed earlier: The family will run out of supplies. Symbolically, the candles. Once the family runs out of candle light, everything inside the boarded-up house will be completely dark. A metaphorical death.

To understand the ending, we must go back to the beginning: Now the birds have lost their desire to feed, they are ‘never satisfied, never still’.

I see no reason to think the family made it through the bird attack, only symbolism pointing to eventual demise. The birds will continue to sacrifice themselves, in some mass ‘beaching’ event (as incomprehensible to us as whale beachings) and then the Earth will be silent.

RESONANT IMAGERY

There’s no jungle gym in du Maurier’s short story. There are no love birds, no one with movie-star looks. No one rows a boat across the water. These are magnificent images and have contributed to the longevity of the story.

But the short story must have resonant imagery of its own, right?

Yes. White-capped waves on a choppy sea. When examined more closely, Nat is shocked to learn the white caps are not made of water at all, but flocks of birds heading for land, where they will attack humans.

An effective horror trope: A character sees something ordinary, but on closer inspection realises it’s not what they thought at all. A regular, everyday thing — something part of the landscape — is revealed to be a monster. In ancient mythology we find examples such as hills which are actually sleeping giants. (Can you think of other examples from modern storytelling?)

By coincidence (?) towering, terrifying waves have become the universal symbol of fears around climate change, probably associated with fears around rising sea levels.

See: The Three Types of Symbolism.

SETTING OF “THE BIRDS” SHORT STORY

“The Birds” was published in her 1952 collection The Apple Tree. (I’m reading a more recent printing, now named The Birds and Other Stories.)

PERIOD

On December the third the wind changed overnight and it was winter.

opening sentence to “The Birds”

DURATION

a story’s length through time. Maybe it takes place over a year, cycling through each season. Maybe it takes place over 24 hours.

LOCATION

A farm on a peninsula with sea on either side of the farmland. South coast of England.

ARENA

The Hocken family never leave the peninsula but they can see out to sea, and they hear via radio that birds are affecting other parts of the UK.

MANMADE SPACES

Nat Hocken lives in a farm house with his wife and two children. It’s basic even for the 1950s, with candles for home lighting. They’re better off than people with more modern amenities. Even so, Nat’s wife notes that they’d have been better prepared for this siege in the old days, before local shops got everyone into the habit of buying supplies, rather than stocking up out of necessity. When the birds attack, they are due to get new supplies in the following day, and have barely enough food and light to sustain them for a few days.

NATURAL SETTINGS

The opening paragraph describes a beautiful, bucolic setting which can’t possibly last. The red of those autumn leaves must create a colourful scene beside the blue of the ocean. But when a story opens with a beautiful red, gird your loins for possible blood.

WEATHER: an allegory for climate change and pandemic lockdown

The birds are basically a weather event. Or perhaps a climate event. “The Birds” feels horribly timely, as we blunder towards climate catastrophe, not yet averted.

Even here in Australia, I know people who ‘don’t believe in’ climate change, though evidence is all around us, right here in this country. These people will explain the fires and floods away, saying it’s just normal fluctuation. This is exactly how Nat’s neighbours respond when he asks them, Have you noticed anything weird about the birds? What about those birds, huh?

Obviously, Daphne du Maurier wasn’t writing a climate change allegory on purpose. (Scientists knew that climate change would be the end result of the industrial age and could see the changes.

Evidence that I know of: a 1912 clipping from a New Zealand newspaper:

Coal Consumption Affecting Climate

The furnaces of the world are now burning about 2,000,000,000 tons of coal a year. When this is burned, uniting with oxygen, it adds about 7,000,000,000 tons of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere yearly. This tends to make the air a more effective blanket for the earth and to raise its temperature. The effect may be considerable in a few centuries.

14 August 1912, Rodney and Otamatea Times, Waitemata and Kaipara Gazette

Post covid-19, the experience of locking oneself inside the home surrounded by family, worried about your country’s food supply-chain (and toilet paper) is also highly relatable, especially for those of us whose countries locked down.

But in the early 1950s, when Daphne du Maurier was concocting this story, everyone was reeling from two World Wars. Contemporary readers would have been reminded of shell shock, of wartime sirens, of the divide between London and the rest of England (where London is thought to look after itself first). The threat of things falling from the sky was still top of people’s minds. War traumatises at a population level.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

Chimneys have terrified for a long time. An entire mythology has evolved around them. Demons come down the chimney because they are open to the outside world. (Houses catching on fire are far more likely, as is respiratory disease from smoke-filled living areas, so this is a misplaced fear.) Imagery of child chimney sweeps being stuck in chimneys has also remained in the cultural imagination — perhaps seldom considered now, but more recent in the minds of a 1950s readership.

Since chimneys are vital for survival (for warmth as well as for cooking food), Nat is unable to cover the kitchen chimney. The chimney demons are birds.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

As an introvert and a disabled war veteran who lives on a remote peninsula, Nat is already separated from the dominant culture. Daphne du Maurier clearly decided not to go the whole hog and make him the full-hermit. She gave him a family. A family helps tell the story. With no family to care for, Nat’s survival instinct may not kick in.

Although the bird invasion is a national emergency, du Maurier paints the picture of a family isolated in their vulnerability. Nat was the first in his area to become concerned about the birds. No one else took it seriously.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE

This particular fear finds various outworkings in stories. There’s the Last Man On Earth story — amazingly common. You’ll find a story like that in pretty much every short story collection — including this one. “The Birds” is it.)

You’ll recognise Man Alone stories because other people are around but they behave like automatons. There’s no loneliness like the loneliness of crowds, where no one believes you, no one identifies with your fears and no one else sees the existential looming threat to society.

SEE ALSO

See also: Episode 60 of the Then Again Podcast: Alfred Hitchcock’s Art of Suspense. “Special guest and movie buff Matt House discusses the techniques and methodology of Alfred Hitchcock’s thrillers.”