“The Bear Came Over The Mountain” is one of the 25 Alice Munro Stories You Can Read Online Right Now. (There’s a possible paywall.) Sarah Polley adapted this short story for film. The film is called Away From Her. This story was first published in The New Yorker (December 27, 1999 and January 3rd, 2000).

THE TITLE OF “THE BEAR WENT OVER THE MOUNTAIN”

Why is this story named after a popular children’s song?

The main lyrics:

The bear went over the mountain, the bear went over the mountain

The bear went over the mountain, to see what he could see.

And all that he could see, and all that he could see

Was the other side of the mountain, the other side of the mountain

The other side of the mountain, was all that he could see.

I have no idea why, but I have some theories. First, there’s the Sisyphian task of getting up a mountain in the first place, which is life itself. (Sisyphus was a cruel Greek king who was punished to push a large rock up on a steep hill, only to find it rolling back on nearing the top. Ever since, he has been known for pushing the rock tirelessly till eternity.)

When Fiona enters the rest home, she is on the other side of the mountain of life. Now that she has lost her mind, she has also lost her inhibitions, and she is free to pursue love outside marriage, as her husband has done their whole married life. To Fiona, but not to Grant, entering a state of dementia is a kind of freedom. Fiona’s (perceived) journey is from entrapment to freedom, though this particular freedom appears to an outsider as no such thing. (When I say ‘perceived’, I mean perceived by the narrator.) Most of us would consider instalment in a rest home the opposite of freedom, but that is part of Munro’s genius.

The children’s song is sung to a gleeful melody, but there’s a grim repetition to it. There’s a grim repetition to the goings-on inside a rest home, too. Breakfast, cards, morning tea… and so on.

Where did the song come from?

Deitsch folklorist Don Yoder postulates that the song may have its origins in Germanic traditions similar to Grundsaudaag, or Groundhog Day. Groundhog Day is known to have its roots in the behaviour of badgers in Germany. In some German-speaking areas, however, the foxes or bears were seen as the weather prognosticators. When the behaviour of the bear was considered, the belief was that the bear would come out of his lair to check whether he could see “over the mountain.” If the weather was clear, the bear would put an end to hibernation and demolish his lair. If it rained or snowed, however, the bear would return to his lair for six more weeks.

Wikipedia

That description ties the song inextricably to the seasons. Munro takes the reader through the full seasonality of Ontario in “The Bear Came Over The Mountain”. Although the story does not take place over a single year, she makes sure to take the reader through the typical seasons of any given year. We meet these characters in winter, in a thaw, in spring, in summer, though each of these seasons takes place during a different memory or in a different present. Stories set around a full year of seasons tend to symbolise a full life.

Grant’s character arc mirrors that of the bear, encouraging me to read Grant as the titular bear. When he pokes his head back into his marriage, now too old for all his previous shenanigans, he is knocked back with a chilly reception. Grant retreats emotionally from his wife as the bear retreats to its winter lair.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE BEAR CAME OVER THE MOUNTAIN”

SHORTCOMING

Grant makes for an interesting fictional character because he is quite charming on the surface, and Munro first introduces him as a devoted, loving husband. Via her flashbacks to the past, and by leading the reader through this social world via Grant’s view, she affords us a grim insight into his moral and psychological shortcomings, which are significant.

SEXUAL SOLIPSISM

Grant is your archetypal solipsistic sexist man, and that is his main shortcoming (both psychological and moral, since he acts upon his fantasies). That terminology became popular after Rae Helen Langton, published Sexual Solipsism: Philosophical Essays on Pornography and Objectification.

This short story is older than Langton’s theory as a named concept (2009), but Alice Munro wrote about a sexually solipsistic archetype before this guy even had a name.

The solipsistic sexist reduces women to body parts, treats women primarily in terms with how they look or how they appear to the senses, and also treats women as if women lack the capacity to speak. To this man, how a woman looks is more important than what she says. It’s all tied up with ‘objectification theory’. (I’ve written briefly about The Male Gaze.)

Grant’s solipsistic attitude towards women shines through via Munro’s close third person narration every time he encounters a woman in the story. First there is Kirsty. With the phrase ‘who didn’t have much time for him’ we understand Kirsty has had her own off-page arc — she has realised that Grant is using her for emotional labour, over and above the job she is paid to do. Kirsty only has so much time and emotional energy to devote to unpaid psychology work.

In case we miss how he relies unfairly on significant emotional labour from the harried aged care worker who ends up avoiding him, we see it on the page when he visits Marian:

She’d have been appetizing enough. Probably a flirt. The fussy way she had of shifting her buttocks on the kitchen chair, her pursed mouth, a slightly contrived air of menace—that was what was left of the more or less innocent vulgarity of a small-town flirt.

Notice how Grant believes Marian shifts her buttocks on the kitchen chair for his benefit — a ridiculous observation given her chilly treatment of him, and also because it’s impossible to sit on a chair without applying buttocks to it.

We saw it earlier, in his memory of her:

He hadn’t remembered anything about Aubrey’s wife except the tartan suit he had seen her wearing in the parking lot. The tails of the jacket had flared open as she bent into the trunk of the car. He had got the impression of a trim waist and wide buttocks.

She was not wearing the tartan suit today. Brown belted slacks and a pink sweater. He was right about the waist— the tight belt showed she made a point of it. It might have been better if she didn’t, since she bulged out considerably above and below.

Later, Marian calls him and offers an outing. Grant interprets this as sexual interest, though nothing in the scene shown to the reader suggests sexual interest. She even tells him she’s not interested sexually. He ignores this. The reader (hopefully) is in audience superior position, though the risk in writing a story like that is that this interpretation of character is left entirely to the reader, and not all readers will see this guy as I see him.

Alice Munro objectifies the women in “The Bear Came Over The Mountain” mindfully. We know this for sure, because after looking at her corpus of short stories we find she does not write this way about women by default. There are big name male writers out there who do write in a solipsistically sexist way about women, and consistently, across their work, not because they are creating a character who sees the world like this, but because they themselves see the world like this and don’t even realise they’re doing it. Refer to G.R.R. Martin, Ken Follett et al. See also: How To Describe A Woman In Fiction.)

Alice Munro even makes sure Grant ends up comparing this woman to a cat — a pretty good clue that we’re dealing with a sexual solipsist:

The walnut-stain tan—he believed now that it was a tan—of her face and neck would most likely continue into her cleavage, which would be deep, crêpey-skinned, odorous and hot. He had that to think of as he dialled the number that he had already written down. That and the practical sensuality of her cat’s tongue. Her gemstone eyes.

Despite his philandering, Grant has led a privileged life. A similar fictional character is Joe Castleman of The Wife by Meg Wolitzer. The spousal dynamic is similar, too. He has made an academic career for himself on the back of his wife’s heritage, not his own. He even ends up living inside her childhood home. But precisely because of this privileged life, he hasn’t had any character arc until now, when his privileged life is almost over.

DESIRE

The movie [and the short story] spares us coy early scenes where she seems healthy and then starts to slip; she starts right out putting a frying pan into the refrigerator.

Roger Ebert review

Grant wants to start fresh in retirement after a lifetime of philandering, which has become a bit of a nuisance at his age.

Unexpectedly, his wife must go into a care facility because she has Alzheimers. His desires shift slightly, and Munro surprises us by going against the predictable. Absence makes the heart grow fonder.

OPPONENT

Grant’s romantic opponent is his own wife, since he wanted to rekindle the flame and she has lost her mind.

A love triangle happens, which makes Aubrey an opponent. But this is not the main opposition in the story. The reader as well as Grant himself understands that dementia patients don’t make strong opponents. Real opposition requires intent.

Grant’s real opposition is Kirsty (who steps back from providing him with emotional labour) then Marian, who he must persuade in a variety of ways.

Marian is the proxy for his own wife, and it is Marian who faces Grant in the ‘big struggle scene’.

I wondered if Marian is a symbolic name. Marian is a variant of Marion, a French diminutive form of Marie, which is derived from the Hebrew Miryām, a name of debated meaning. Many believe it to mean “sea of bitterness” or “sea of sorrow.” Grant is almost certainly a symbolic name — Grant ‘grants’ permission to his wife enjoying intimacy with another husband. Fiona means ‘white’ or ‘fair’, which feels like an Icelandic landscape, and also like the landscape in an Ontario winter.

PLAN

Grant’s plan is to go with the flow. But this never makes for a satisfying story. So something happens to throw Grant into disequilibrium, and when Aubrey’s wife pulls him out of the care facility this sends Marian into a depressive state.

Grant’s plan: To persuade Marian to take Aubrey back for visits.

BIG STRUGGLE

The Battle of this story happens in the kitchen/living room area of Marian’s home. I’ve written about the depiction of this room separately.

Marian has been written as the proxy character for Fiona, too far gone to ever confront Grant about his past. Munro is sure to point out how Marian and Fiona are opposites. According to Grant Marion has segmented beauty; Fiona’s is whole. Marion did not grow up here; Fiona is living in her childhood house.

What I think is he did something pretty stupid. But I’m not supposed to ask so I shut up.

Marian, in “The Bear Came Over The Mountain”

Marian and Grant having a conversation about Aubrey is the proxy for Fiona and Grant having an honest conversation between themselves about Grant’s philandering, which will never happen because the opportunity for that has passed.

ANAGNORISIS

Does Grant undergo any change over the course of this story?

Early in the narrative, Munro describes the faces of Fiona’s beloved dogs before they died. This is more than a Save The Cat (okay, Save The Dog) paragraph, which might function only to show that Fiona is a caring person and also childless. The dogs’ faces are described as ‘intransigent’, which means unwilling to change one’s views or agree about something. ‘And Grant himself…” begins the following sentence, linking Grant to the dogs somehow, without actually linking.

Near the end there is a cut from Grant contemplating the crepey breasts of Marian to Grant visiting his wife in the rest home.

…Her gemstone eyes.

[CUT]

Fiona was in her room but not in bed….

Grant embraces Fiona and tells her he’ll never stop coming to visit.

“The Bear Came Over The Mountain” is an excellent example of a deliberately ambiguous ending.

Has Grant really brought Aubrey with him?

- STRAIGHT READING: Grant has brought Aubrey, which tells us that Grant has met up with Marion and managed to persuade her to let him come.

- TRICKY READING: Grant hasn’t brought Aubrey at all. Fiona doesn’t remember names these days, or faces, so Grant may be posing as Aubrey in order to please her and to relive some of the old spark.

It is left up to the reader to decide whether Marian and Grant are going to find comfort in each other.

NEW SITUATION

Whether they do or don’t is up to Marian. I don’t get the feeling she’s up for it.

In any case, I don’t believe Grant has changed at all. Grant’s character arc reminds me of Randy the Ram’s character arc in The Wrestler. He spends his whole life treating women close to him badly. An illness (his wife’s) makes him reevaluate his priorities. But this doesn’t go exactly as he planned (because she falls for someone else in the rest home, not for him), and he copes with this not by changing but by doubling down on old habits. Grant’s old habit: Finding comfort in peripheral other women, looking for some point of attraction until he’s actually attracted to them.

But this ending is not as tragic as the ending in The Wrestler. Grant is no underdog. He is perfectly capable of finding his own happiness, and justifying it all to boot. Moreover, he has a strength to compensate for his moral shortcoming: He is able to provide what his wife needs because he understands her so well and is able to conquer jealousy. This feels like a happy ending to me.

RELATED LINKS

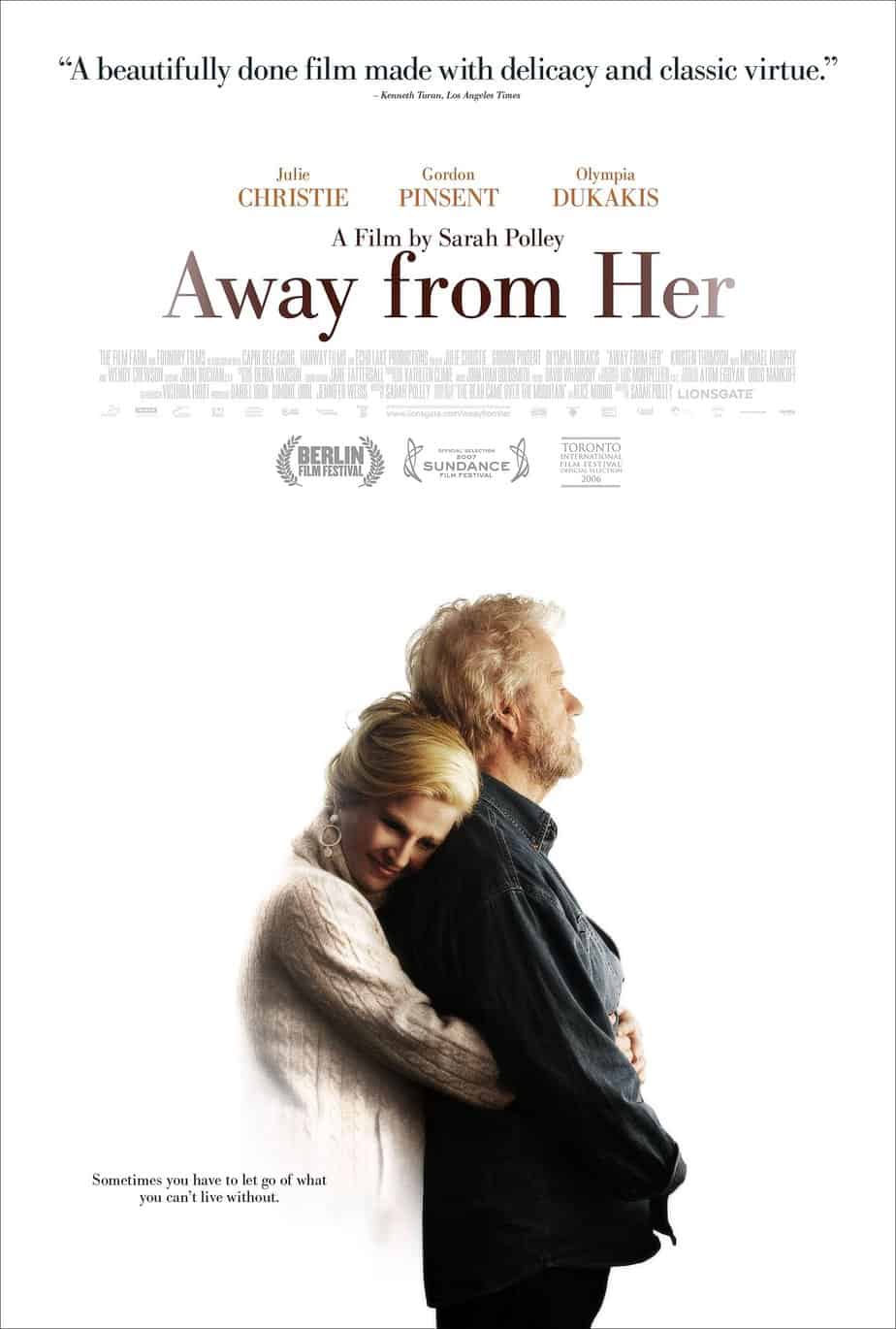

- Someone has analysed the film poster of Away From Her, which I stumbled across by accident.

- Away From Her at IMDb. The film follows the short story closely.

- The History of Literature podcast produced an episode called “The Genius of Alice Munro”. Most of the episode is about “The Bear Came Over The Mountain”.

- Storygrid Editor Roundtable also tackled this story.

- A podcast discussion at The History of Literature, 23 Oct 2017