Across all forms of storytelling the beach functions as an alternative, liberating space, almost a heterotopia. The beach is also a liminal space, partly because it forms the boundary between land and sea.

The beach as a tourist destination is also a liminal space because visitors can “enjoy experiences and feelings that are often repressed in conventional public spaces” (Andriotis, 2010). Some beaches around the world tolerate nudity and drug use, making these “marginal paradises where no laws exist” even more of a drawcard to tourists seeking a completely different experience from the one they’d have at home.

The beach takes characters away from the intellectualism and emotional cynicism of the modern city.

THE BEACH IN FANTASY

The beach contains hidden treasure and fantastical elements. (For example in the short stories of Paul Jennings.)

LIFE AND DEATH

The beach is a space in which characters explore their own relationships to life and death. (Katherine Mansfield short stories.) In common with liminal spaces more generally, there is a thin edge (or veil) between the light side and the dark side (or life and death, summer and winter etc).

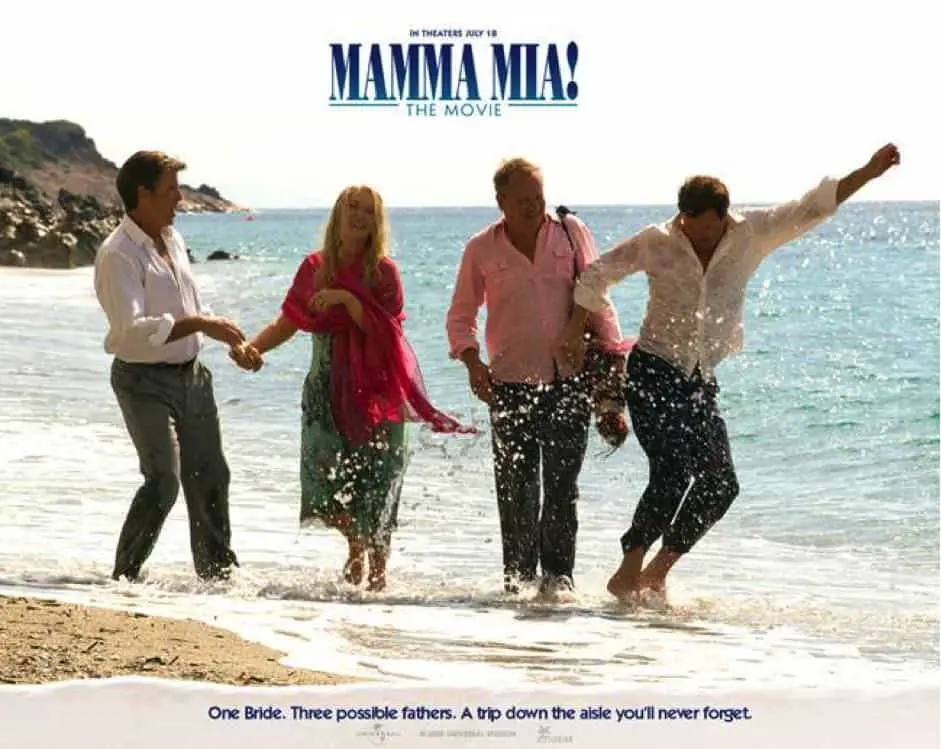

THE BEACH IN ROMANTIC COMEDIES

Within romantic comedy, the setting of the beach has come to function as a highly potent and privileged setting, evolving into a generic ‘magic space’ that sanctions and protects those desiring love, while allowing for certain forms of speech involving intimacy and the (sexual) self that cannot be uttered elsewhere.

Time and again, the sea functions as an alternative, liberating space away from the intellectualism and emotional cynicism of the modern city, constituting an arena where characters can find intimacy and give themselves over to love in ways impossible elsewhere.

The sea also suggests the elusiveness of everlasting love. The meaning of the sea in romantic comedy is not entirely stable. It is used to endorse romantic notions about ‘authentic’ love and natural ‘soulmates’. But that’s not all: a certain paradox is at play in the genre’s use of the shoreline, since the liminal space of the sea/beach stands simultaneously both for enduring natural wonder that will outlast each of us, and the very essence of evanescence. Always changing, never fixed, inescapably different from one day to the next, it is a reminder of the capriciousness of love and life, an expressive signifier which by its very nature reminds us of the transience of all things.

notes from the abstract of Sea of love: place, desire and the beaches of romantic comedy by Deborah Jermyn; Janet McCabe

THE BEACH AS WOMB (UTOPIA)

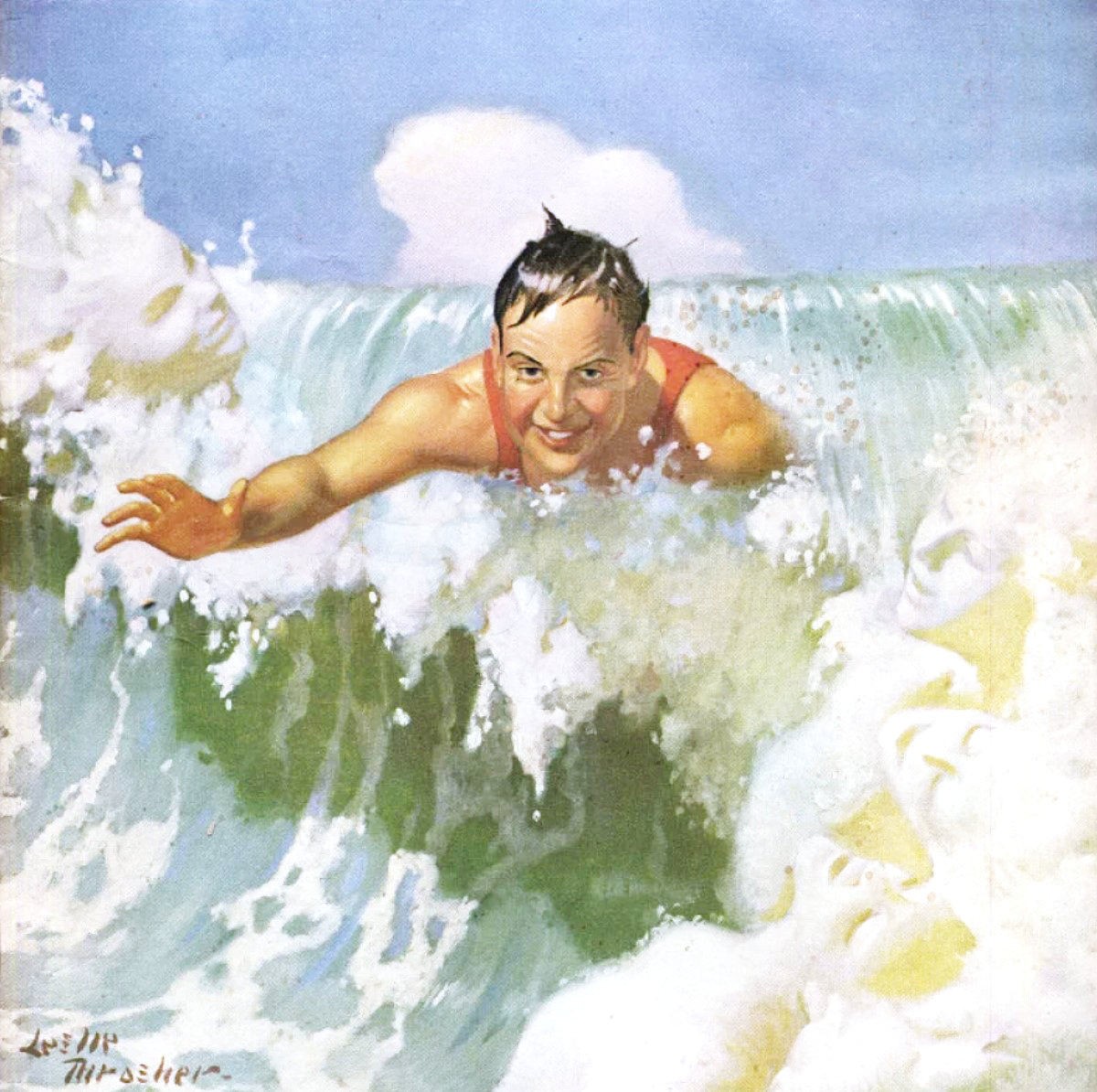

There are also obvious connections between swimming in the water and being housed safely inside your mother’s body. Less obvious, perhaps, is the way the sea can transgressively return us to a primitive time:

In the womb we swim in salty water, sprouting residual fins and tails and rudimentary gills, turning in our little oceans, queer beasts that might yet become whales or fish or humans. We first sense the world through the fluid of our mother’s belly; we hear through the sea inside her. We speak of bodies of water, Herman Melville wrote of “the times of dreamy quietude, when beholding the tranquil beauty and brilliancy of the ocean’s skin”.

And when we return to swim beneath that skin, our identities and stories are blurred and reinvented. Jellyfish – ancient evolutionary survivors that predate and may yet outlive us – change sex as they mature; cuttlefish and moray eels slip from one gender and back again, shape-shifting in the alien deep. Ever since we began, we have found an affinity in this mutative place and its sense of the sublime.

The Guardian

THE BEACH IN LOVE TRAGEDIES

In case you hadn’t heard, Nicholas Sparks does not like his masterful works of art to be labelled ‘chick-lit’; he prefers the term ‘love tragedy’.

The symbolic function of the beach in a love tragedy seems to be exactly the same as it is in a romantic comedy, with emphasis on the ephemeral nature of everything, including sublime happiness.

Roger Ebert understood the reason for the popularity of Nicholas Sparks love tragedies:

‘ The Lucky One’ is at its heart a romance novel, elevated however by Nicholas Sparks’ persuasive storytelling. Readers don’t read his books because they’re true, but because they ought to be true.

Roger Ebert

THE BEACH AS SETTING IN GOTHIC FICTION

Traditionally, gothic settings contain old buildings, misty moors and the like.

In a young country like New Zealand there are no medieval castles. However, there is always the beach. The beaches of NZ have a haunted history which takes the place of Europe’s castles and dungeons.

The beach can therefore function as a gothic setting in its own right.

The coast can have a binary role:

- offers restoration

- be home to all sorts of strange creatures and happenings

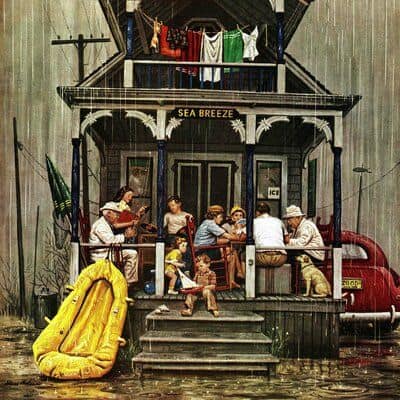

We associate the beach with warm, sunny weather. To change up the weather is to offer an ironic take on archetypal beach setting.

The beach as a site of destruction

THE BEACH AS HORROR ARENA

It follows naturally from the life and death proximity that the beach as a setting also functions as a horror space.

THE BEACH AS CORNUCOPIA

The seashore as a place to play

STORIES WHICH END AT THE BEACH

Because the beach is such a symbolic place, ending a character’s journey beside the sea is left with the audience as a proxy for so much more. Katherine Mansfield does it in “The Wind Blows“. After a long, windy day, the teenage girl main character ends up looking out at the sea.

Richard Ayoade has his main character run to the seaside and there he is joined by his problematic girlfriend. They stand in the water together.

This isn’t so dissimilar to Thelma & Louise, who end up in the canyon, but together. (The canyon was created by a body of water.)

The French Film 400 Blows also ends with the main character running to the sea. The outtake is a freeze frame of his face.

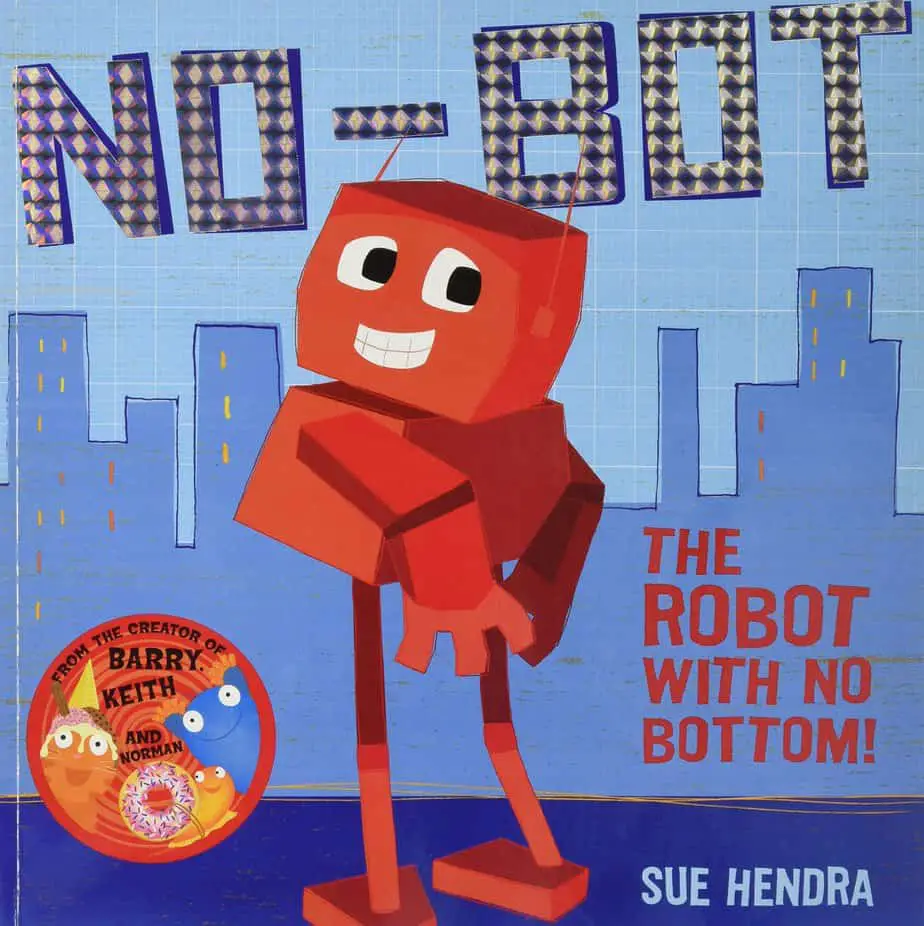

No-bot The Robot With No Bottom by Sue Hendra is a picture book example. A robot loses his bottom, and goes off on a Holy Grail plot to find it. Many things in the world look like robot’s big red missing bottom and he fails to find it, sinking into despair. Here’s where the title earns itself: He is no longer a robot but a no-bot. He runs to the beach. Why? Because that’s what characters often do when they fall into a pit of despair and are all out of ideas. (Yes, he does find his bottom at the beach. At first he thinks some rabbits are using it as a boat, but it turns out it’s being used as a bucket to make sandcastles.)

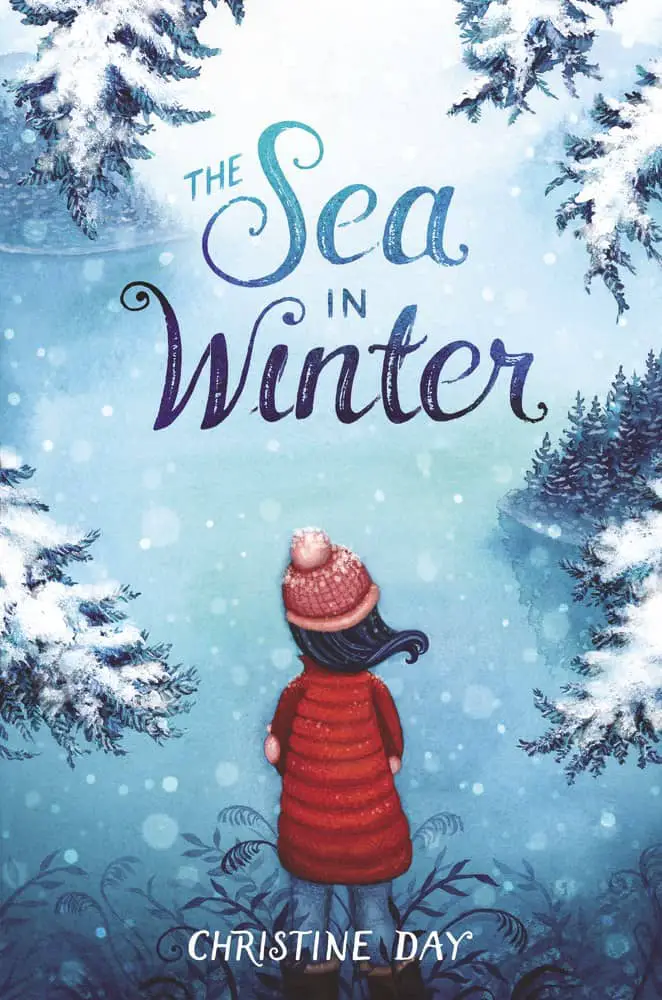

The story of a Native American girl struggling to find her joy again.

It’s been a hard year for Maisie Cannon, ever since she hurt her leg and could not keep up with her ballet training and auditions.

Her blended family is loving and supportive, but Maisie knows that they just can’t understand how hopeless she feels. With everything she’s dealing with, Maisie is not excited for their family midwinter road trip along the coast, near the Makah community where her mother grew up.

But soon, Maisie’s anxieties and dark moods start to hurt as much as the pain in her knee. How can she keep pretending to be strong when on the inside she feels as roiling and cold as the ocean?

My interpretation of this rush-to-the-seaside as a story ending: The seaside is functioning similarly to how crossroads function narratively. The main character has come to the edge of a chunk of their life just as they have come to the edge of the land, things are about to change completely and the flat bed of the ocean afford them a view of the grand scheme of things. And since the sea is scary, we are left with the sense that their life from here on will include danger — storms, choppy waters and no guarantee that they will get to where they want to end up.

For an example of a (wordless) picture book featuring an ocean described as almost being a character in its own right, see Wave (파도야 놀자) by Suzy Lee (2009).

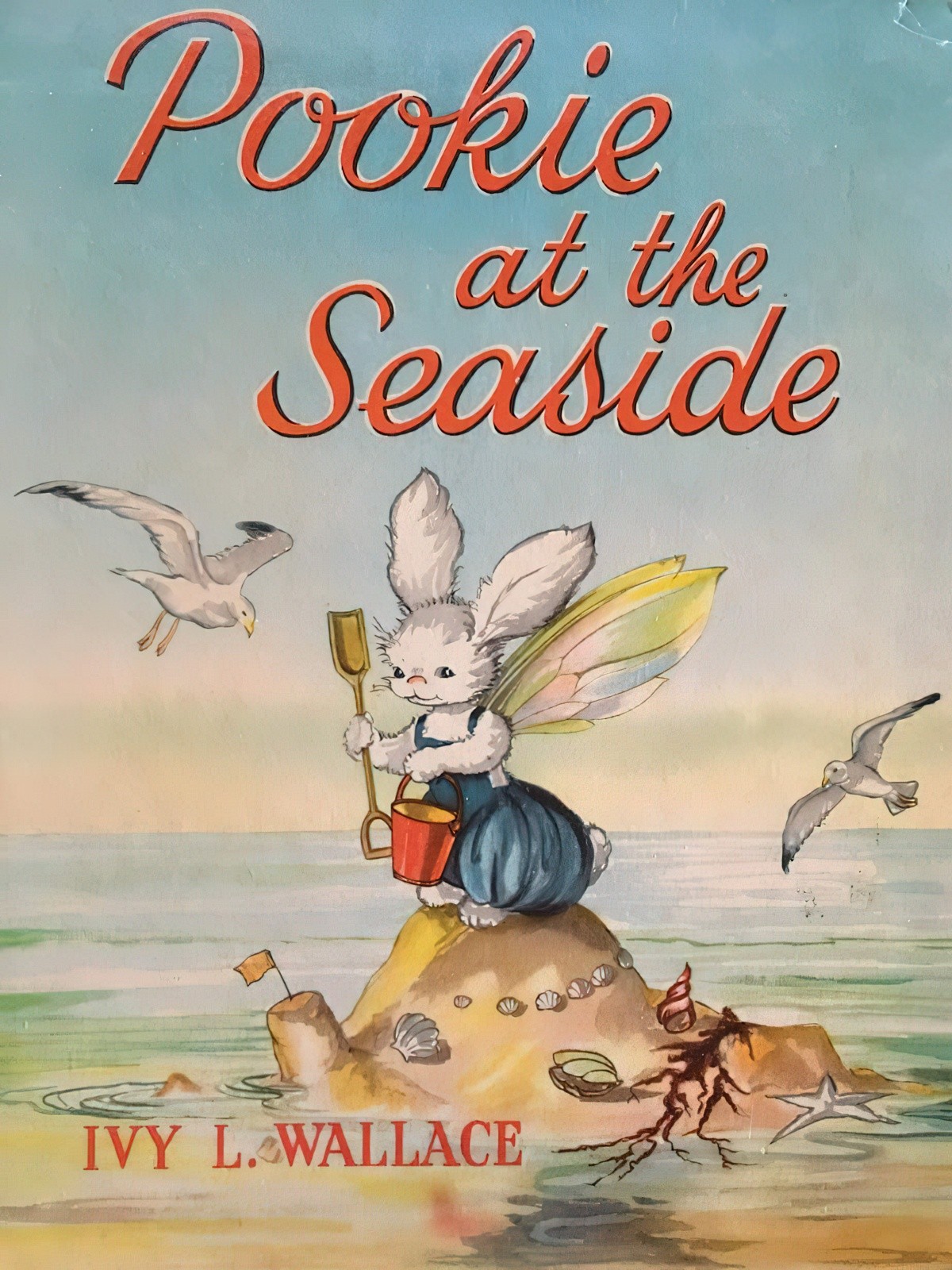

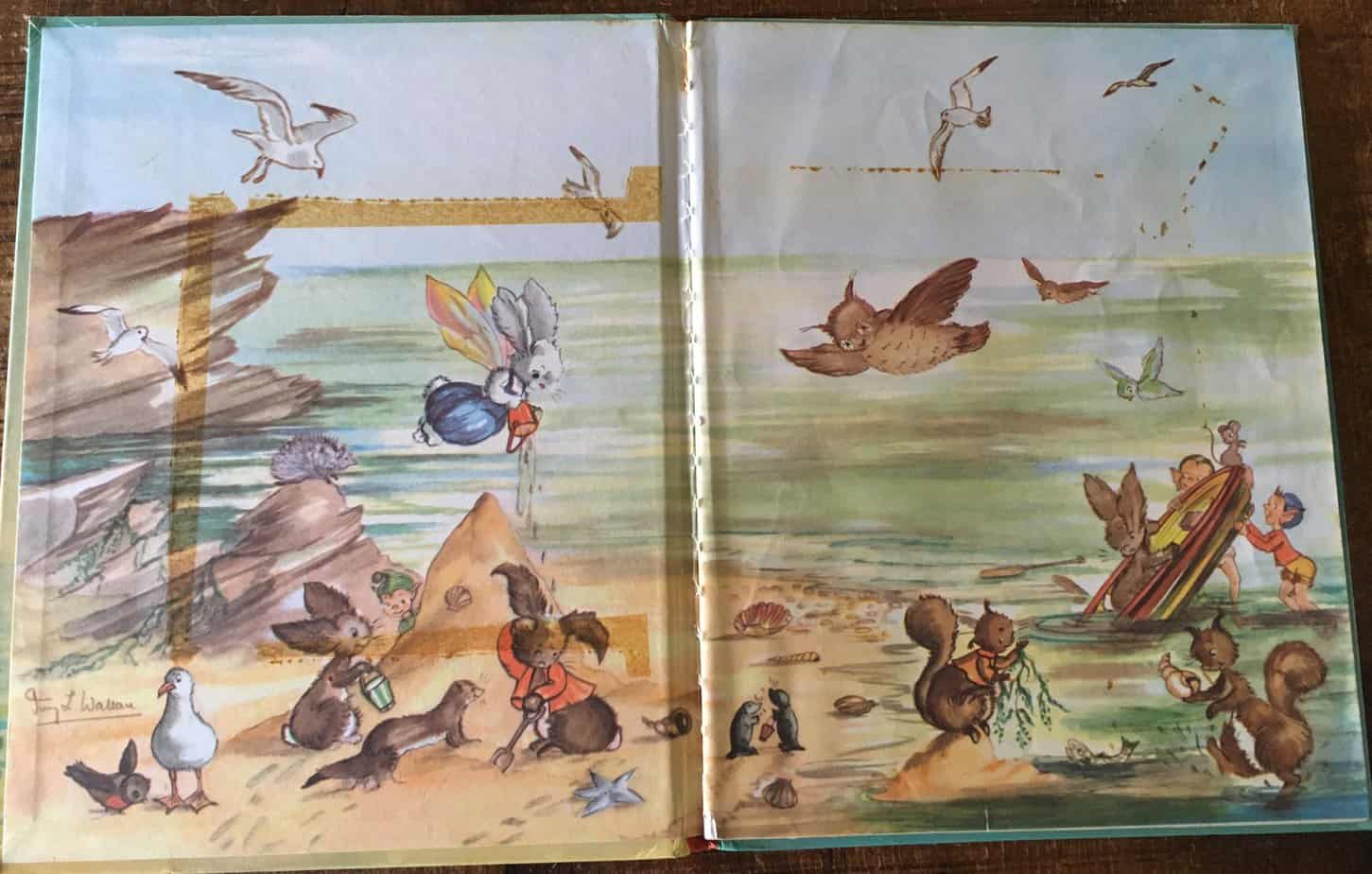

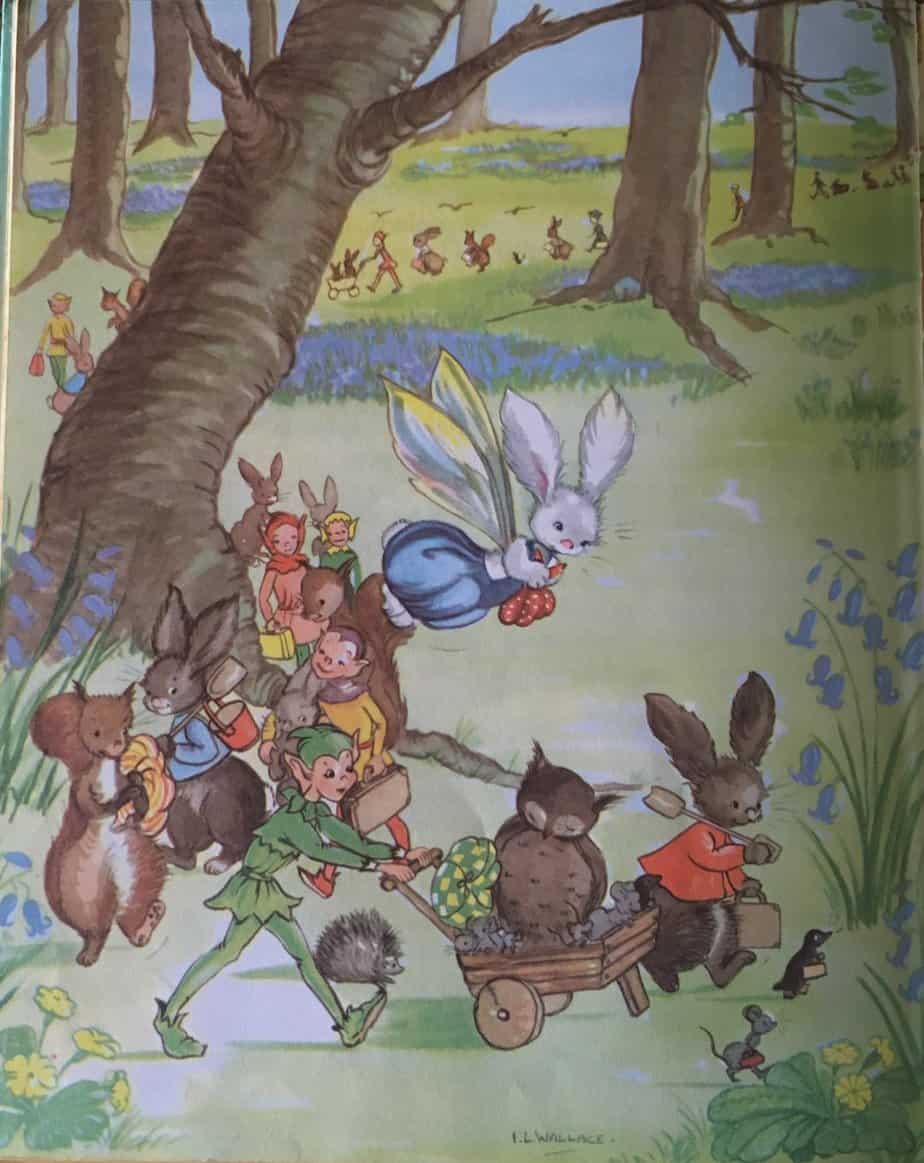

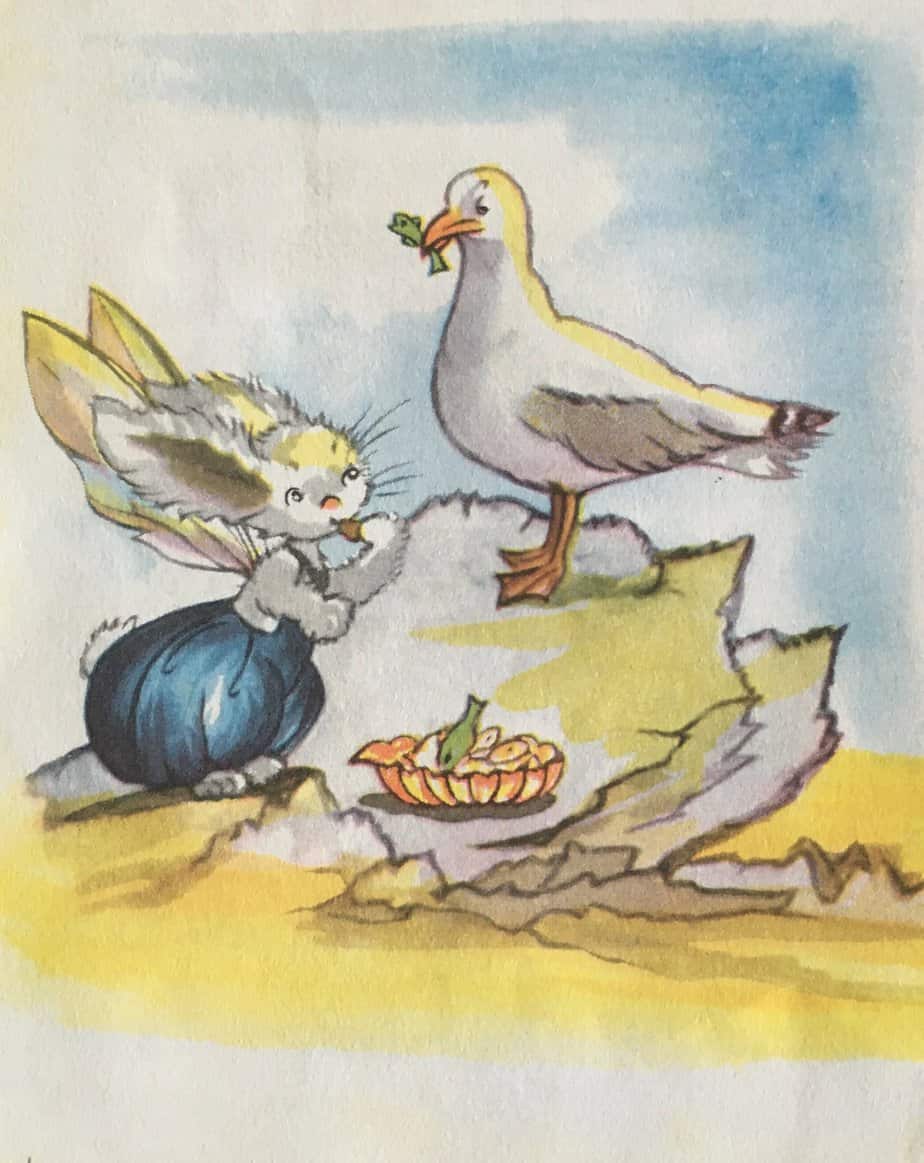

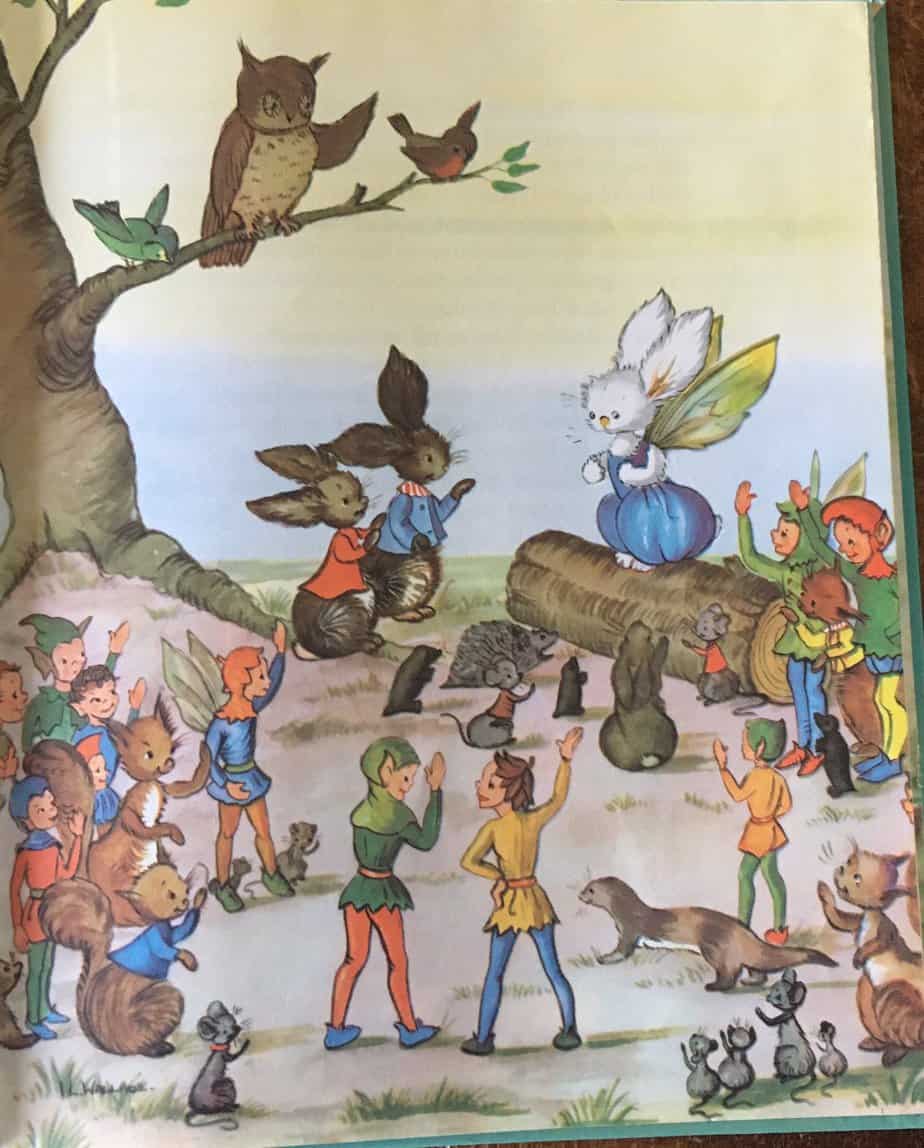

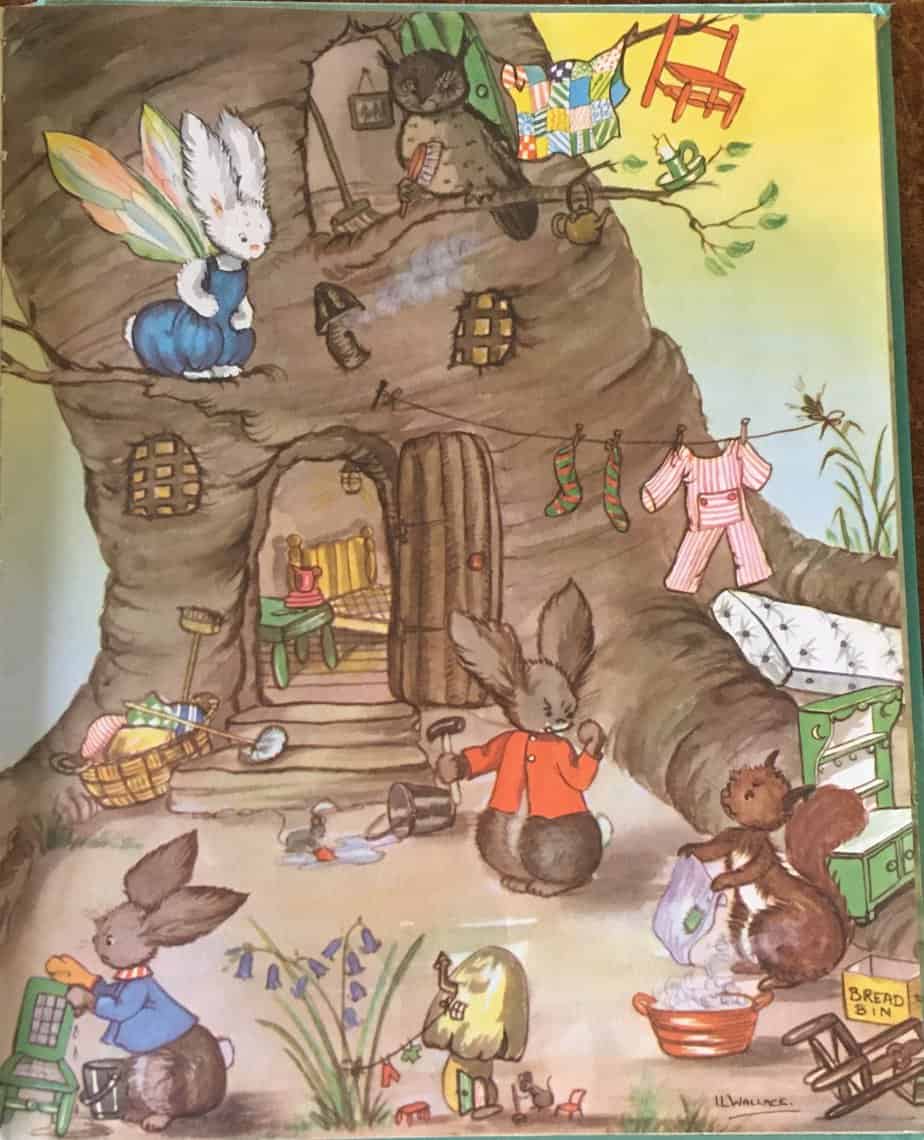

POOKIE AT THE SEASIDE BY IVY L. WALLACE

TRIP TO THE BEACH AS FILLER EPISODE IN LONG-RUNNING TV SERIES

Many long-running TV shows have an episode where characters visit the beach. This episode is often considered ‘filler’ content and includes its own tropes. See Beach Episode at TV Tropes. More than ‘filler’, beach scenery offers a novel setting for viewers. Novelty is hard to come by in long-running shows.

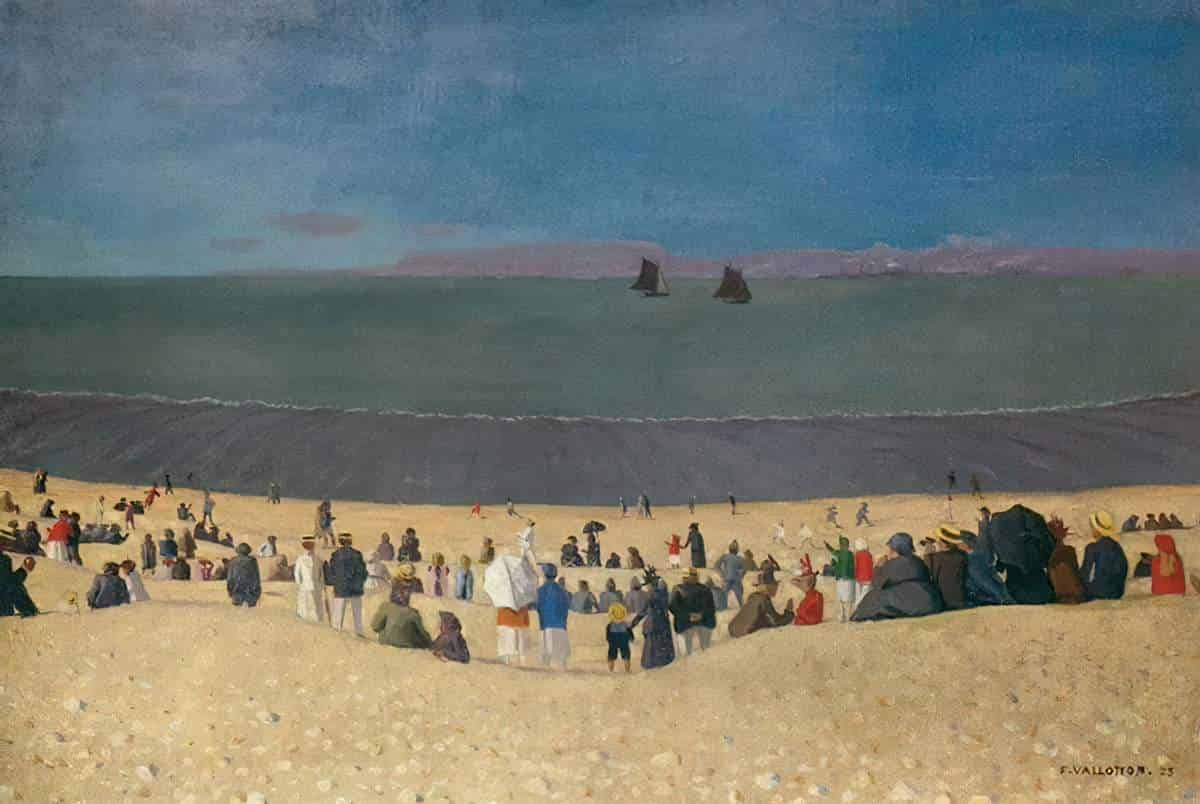

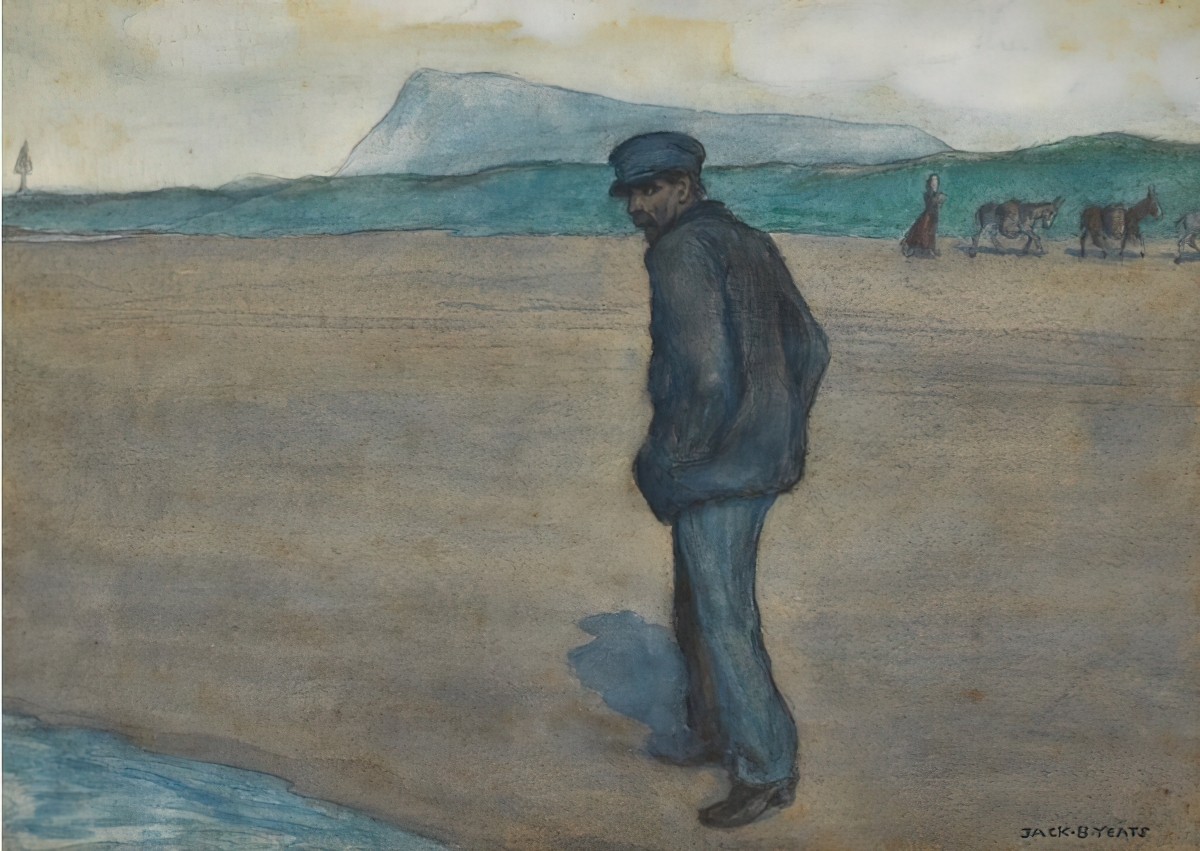

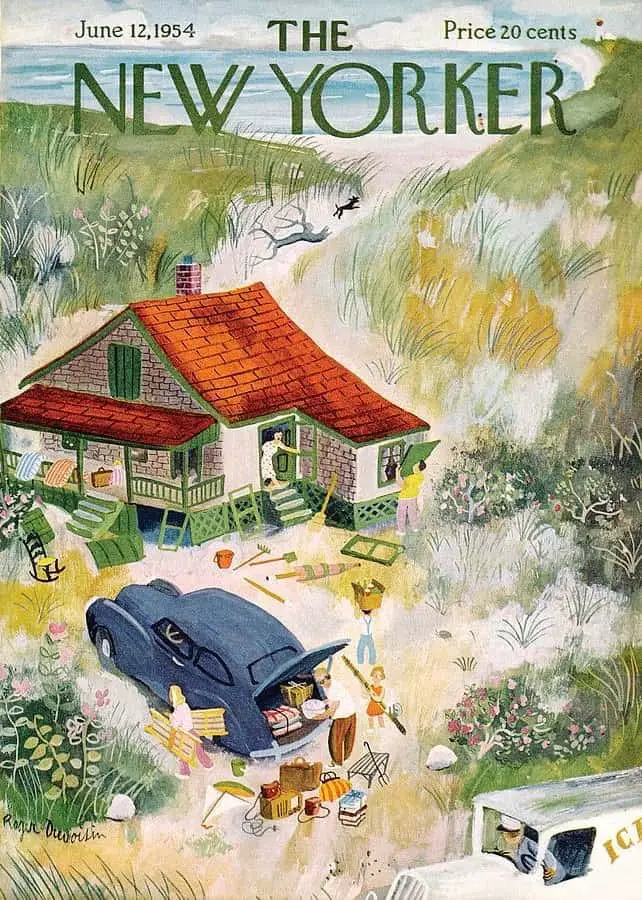

Header painting by Atkinson Grimshaw – Scarborough Beach