“The Art of Cooking and Serving” is a short story by Canadian author Margaret Atwood, included in Moral Disorder and Other Stories (2006).

These interconnected stories all feature a woman called Nell at various times in her life. The stories are not arranged in chronological order. Is it about Margaret Atwood herself? Not directly, but Atwood’s own childhood in the woods is clearly influential.

I’m working on my own life story. I don’t mean I’m putting it together; no, I’m taking it apart.

Margaret Atwood

This second story in the Moral Disorder collection juxtaposes against the first. Nell is a girl, whereas before she was an old woman. Nell is literally on an island, cut off from news of the world (WW2), whereas before she was having to make a conscious effort to rid herself of the constant intrusion into her thoughts.

MORAL DISORDER BY MARGARET ATWOOD

- “The Bad News“

- “The Art of Cooking and Serving“

- “The Headless Horseman“

- “My Last Duchess“

- “The Other Place“

- “Monopoly“

- “Moral Disorder“

- “White Horse“

- “The Entities“

- “The Labrador Fiasco“

- “The Boys at the Lab“

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE ART OF COOKING AND SERVING”?

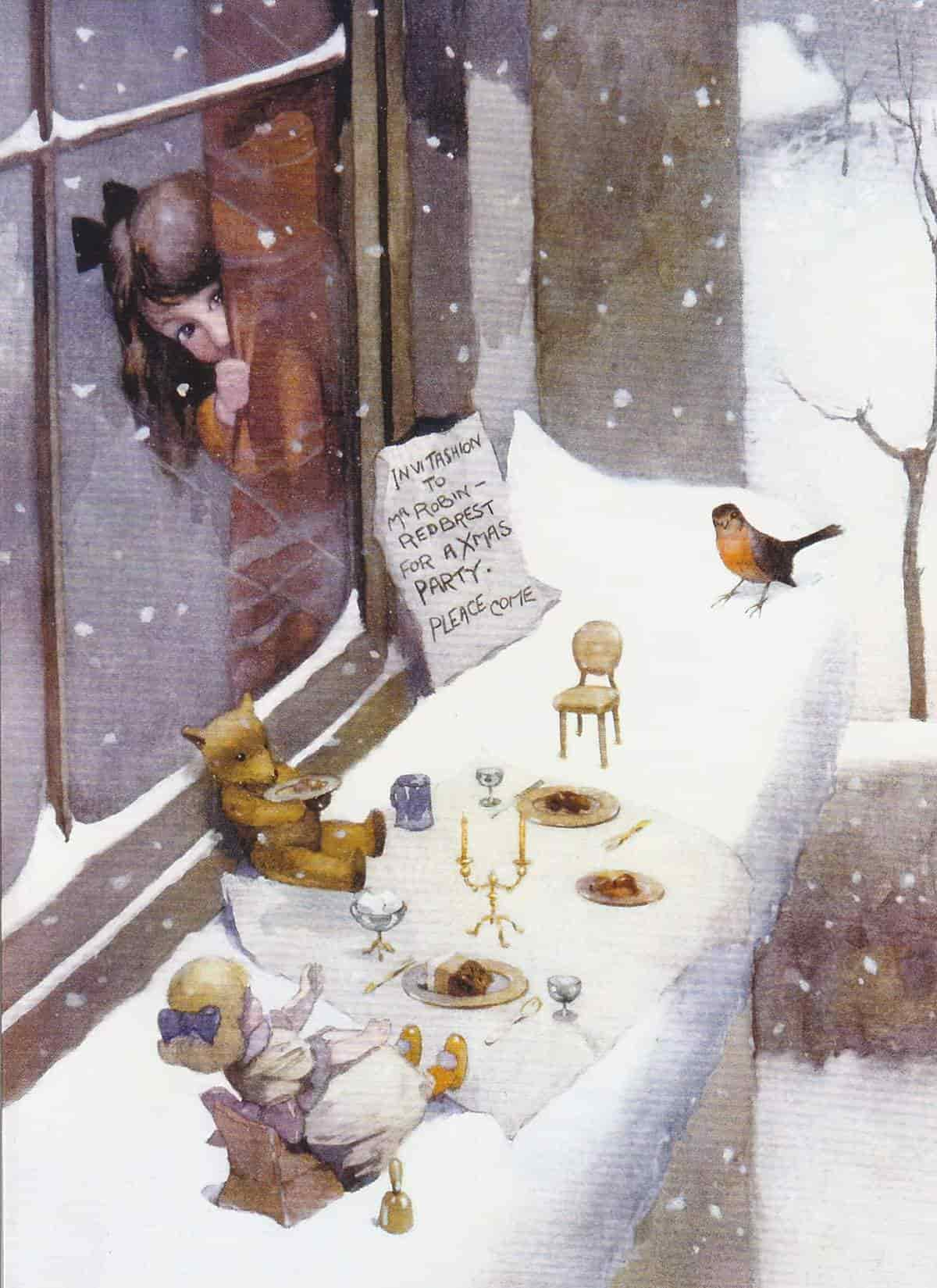

Nell is eleven. It is summer, she is on school vacation and has been taken to an island with her pregnant and very tired mother. Via overheard conversations, Nell understands that her mother did not intend to be pregnant at this age. Old enough to be overhearing things but not yet old enough to understand them, Nell feels somehow that her mother getting pregnant is a deliberate decision to be less than 100% mother.

Still, Nell is an obedient child and is picking up the slack regarding chores. The father is away. It’s just Nell and her mother. Nell worries what would happen if her mother suddenly went into labour. She makes a private plan should that happen.

To take her mind off the anxieties around her mother and the pregnancy, Nell knits a set of baby clothes. She’s proud of it. But when mother and daughter return safely back to town, the mother and her friends make fun of Nell for doing such a quaint thing.

This story makes the beginning of Nell’s adolescence. From now on she’ll be less interested in impressing her mother and her mother’s friends, and more interested in the excitement of her teenage years as a young woman.

Relatable to mothers: The grievance expressed by children when you’re sick and not working at full capacity. Children believe the mother’s job is to be there for them at all times. When otherwise healthy mothers fall ill (or pregnant), children can have a hard time understanding mothers as fully human. fallible people.

Relatable to anyone who has been a child: That feeling of doing something you feel to be serious and praiseworthy, only to be laughed at. You can’t understand why the adults are laughing at you.

The narrative voice of this short story is retrospective and reflective, which allows the experiences of young Nell, told via a more mature narrator, to resonate with people (especially women, perhaps) across the age spectrum.

MARGARET ATWOOD’S CHILDHOOD

When we think of the past it’s the beautiful things we pick out. We want to believe it was all like that.

Margaret Atwood

- Atwood was born in Ottawa in November 1932, a couple of months after WW2 began. As she describes it herself, she was born into a time of great anxiety. Canada entered the war when Britain did, just a couple of days after war was declared.

- Although Atwood was a wartime baby, she spent much of her early childhood in the forests of North Quebec. This means that Atwood didn’t experience war the same way that English children experienced it, forever drawing a line between herself and her British same-age peers. “No one was dropping bombs on Northern Quebec.”

- As a child, Atwood’s city experience of war was blackouts and wartime broadcasts on the radio. “This is London calling North America… [woo-woo noises]”. The ration boats captured the imagination of the children because they brought stamps you could lick. But up in the woods there was none of that. Anxiety lifted.

- The forest lifestyle happened because her father was a forest entomologist. Because insects don’t do anything much in winter, Mr Atwood’s springs, summers and falls were spent doing fieldwork (April through November). He started out specialising in bees.

- Atwood describes her mother as an outdoorsy person who grew up in Nova Scotia and who was very athletic. She was especially interested in horses, speed skating, fast dancing such as waltzing and square dancing and skiing.

- Mrs Atwood liked living in the woods because it meant she wasn’t expected to do much housework. She did have friends in the city, though, and may have missed them a bit over summers. The return to the city and the house peopled with her mother’s friends can be seen in this short story.

- Atwood’s father’s own childhood was even more rural and what probably attracted the pair was that they were both interested in the outdoors.

- Born in 1939 herself, this means Margaret Atwood well and truly remembers how farms used to run in an earlier era. Her life in some ways was similar to lives of the 1800s. Even during Margaret’s childhood, electricity was still being rolled out across Canada (and elsewhere). Her parents didn’t get electricity connected until the late 1950s. They had running water but it had to be pumped. Transportation was by boat. There were no proper roads around there until 1939, and even then, the road was terrible.

- As soon as the War was over, everyone was scared of being blown up by atomic bombs. Atwood was in Boston at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis. She and everyone around her at that time believed a bomb could drop on them at any moment.

- In high school, Margaret Atwood took home economics instead of secretarial sciences, which she kind of regrets because she’s never learned to touch type. It was dangerous for a girl to choose typing back then, because she’d probably be railroaded into being someone’s secretary, though this isn’t why Margaret avoided it. She hadn’t experienced sexism yet. She avoided typing because the girls in the typing class were significantly older and scared her. (They would smoke in the toilets. Some of them were 16 because they’d been failed and held back, whereas Margaret had been pushed forward.)

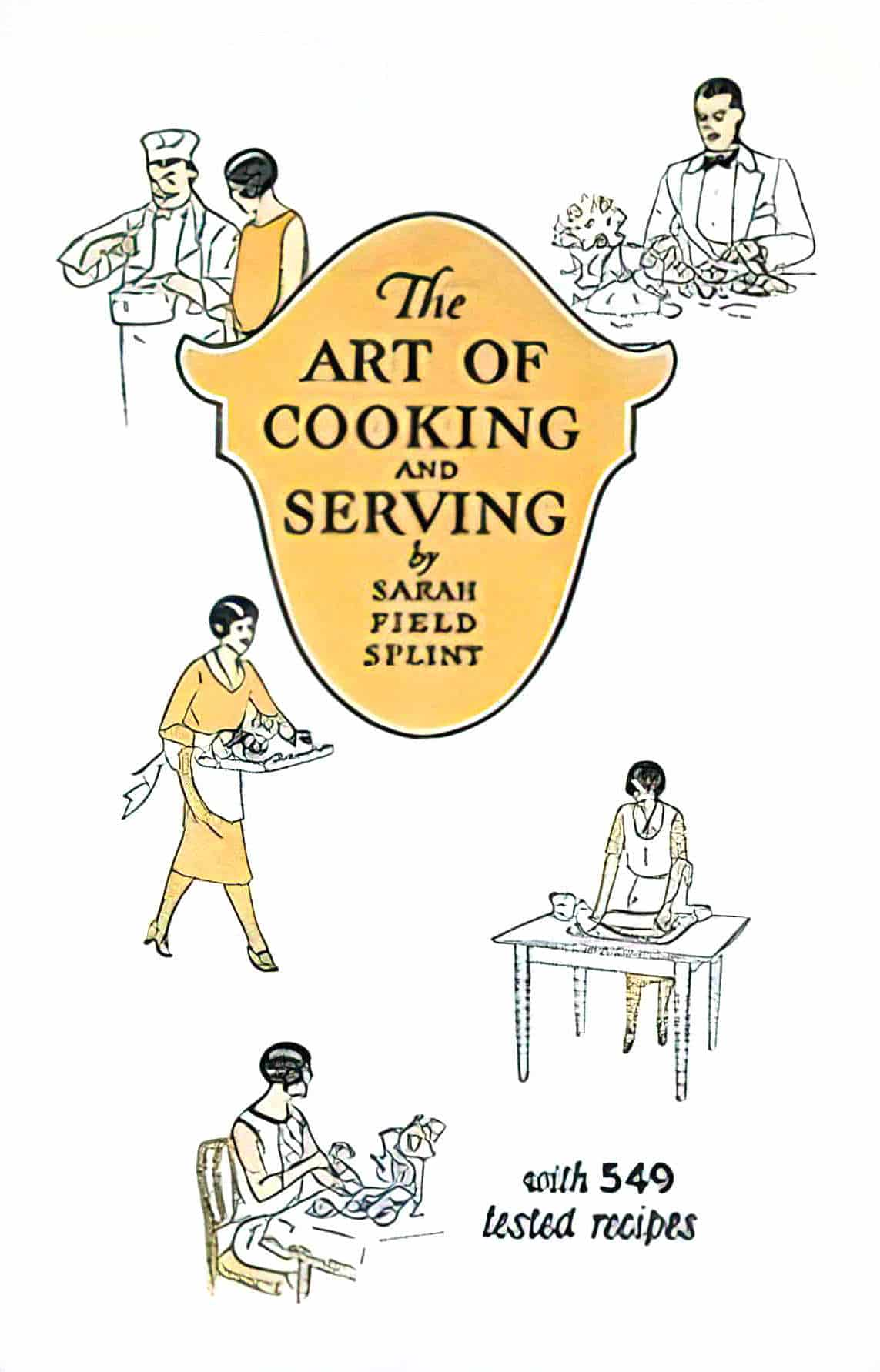

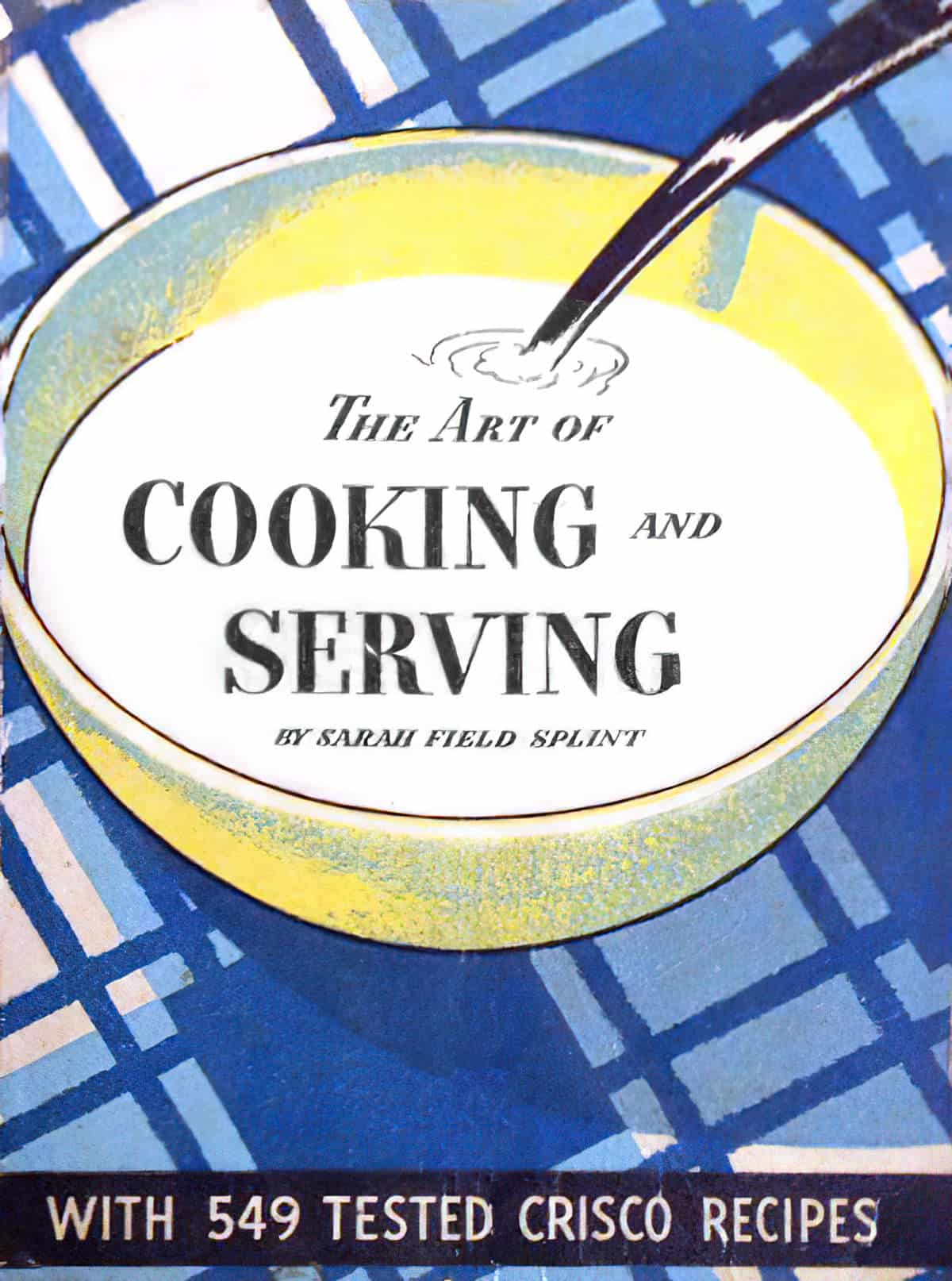

- In “The Art of Cooking and Serving”, a young girl is heavily influenced by a book. Margaret Atwood was also heavily influenced by a book. Margaret chose grade nine home economics in 1952 (rather than typing) because of a book called Guidance. (Kids were expected to know what they wanted to do as a career by grade nine, which Atwood finds ridiculous, and is still ridiculous.) According to this Guidance book, a sum total of five careers were open to young women: Nurse, secretary, teacher, airline stewardess, home economist. Margaret has always been an entrepreneur and figured home economist had a chance of making some money. Also, she knew she’d have to support herself financially when she left school. (Though poorly paid, home economist paid better than the other careers for women.) She later changed her mind and wanted to be a botanist and she probably would have, had she not also been so very good at writing. (Her brother did become a scientist.) She never expected to be able to make a living out of writing, but intended to keep propping her writing career up with service industry jobs (which she says she was never good at, and which exhausted her to the point where she couldn’t write anyway).

- Here’s where Margaret first encountered sexism first hand: At university, Atwood had a professor who advised her to stop messing about with writing and find herself ‘a nice husband’ instead of going to graduate school. This was 1961. I hope that before he died, he heard Atwood reference his sexism in her many interviews.

- Margaret Atwood grew up in an “extraordinarily egalitarian household”, to use her own words. In fact, she made it all the way though childhood and high school without a single person saying she couldn’t do something because of her gender. No one started saying this to her until she was a published poet, when she got “a certain amount of you can’t write really, and women should stop pretending you can. I’ve gotten some, ‘Who would that have come from?’ [laughs] Rival writers who happen to be male. Wouldn’t you know. Yes.”

- Why am I talking about Atwood’s personal experience of sexism? It’s important when reading “The Art of Cooking and Serving” when understanding that the main character is not sewing baby clothes because it is required or even expected of her. This isn’t a story about sexism, as one might expect of a story with this title. Young Nell sewing baby clothes of her own volition.

THE WARTIME EXPERIENCE FOR CANADIAN CHILDREN

The first story of this collection — “The Bad News” — was set in the 21st century, but “The Art of Cooking and Serving” is a look back at how wartime mentality was quite different. Margaret Atwood talks about how mindsets changed across generations in interview with Ezra Klein:

EZRA KLEIN: There’s [a] line that struck me as particularly potent in [The Handmaid’s Tale], […] “How did we learn it, that talent for insatiability?” And you’re talking about the before world, in a way, our world now, the consumer world. […]

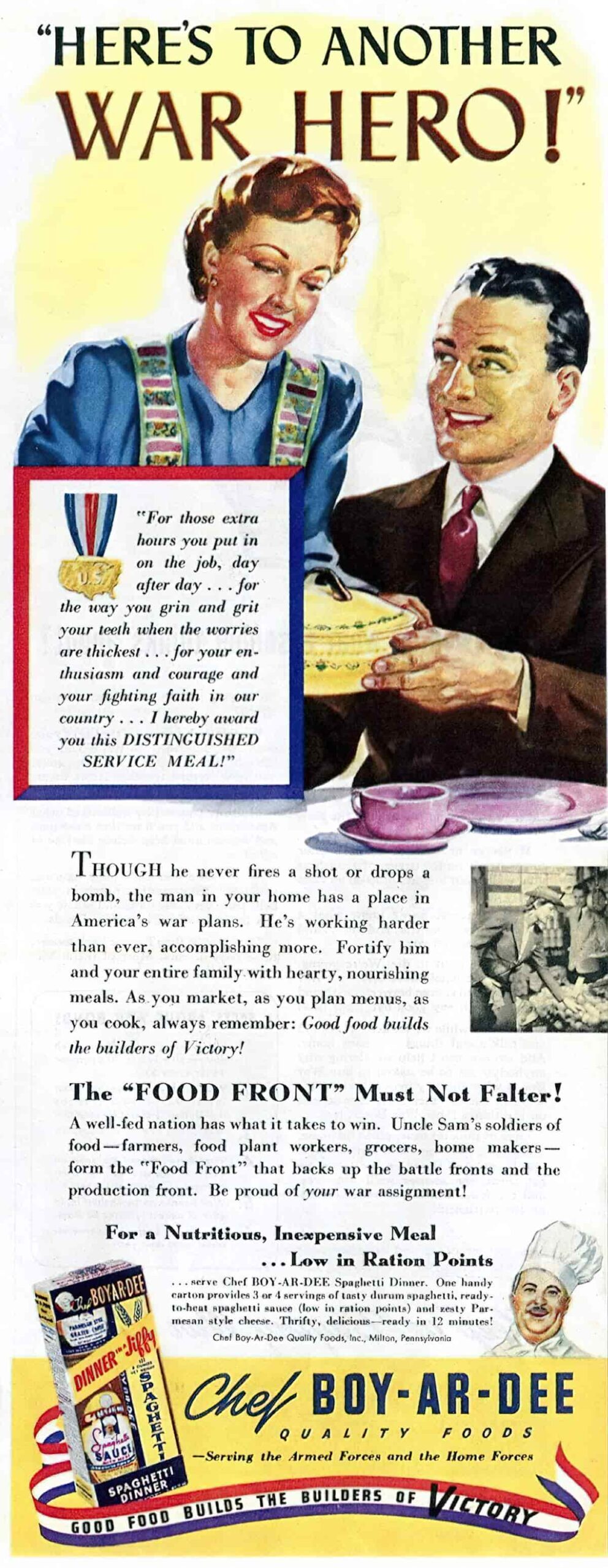

MARGARET ATWOOD: So the talent for insatiability kicks off around 1950, the most recent wave of it. In the ’30s, the virtue was not to waste things. And in the ’40s, that became very much more accentuated because not only did you not waste things, but you saved certain things up because it was the war effort.

So you saved elastic bands. You saved fat in little tin cans. I don’t know what they did with it. You saved newspaper. You saved tin foil. You saved all of those things up. And then they had war salvage drives, and you donated all of those things. You saved up your clothes. You donated them to Europe for people who didn’t have clothes. You never threw things out. And then in came the consumer society, and that has pretty much driven to — because everything is joined at the hip with the energy force driving that civilization. And if you want to read about that, you can get a book called “Art and Energy” by Barry Lord. So every energy source produces a culture which is connected to that energy source.

Margaret Atwood in interview with Ezra Klein

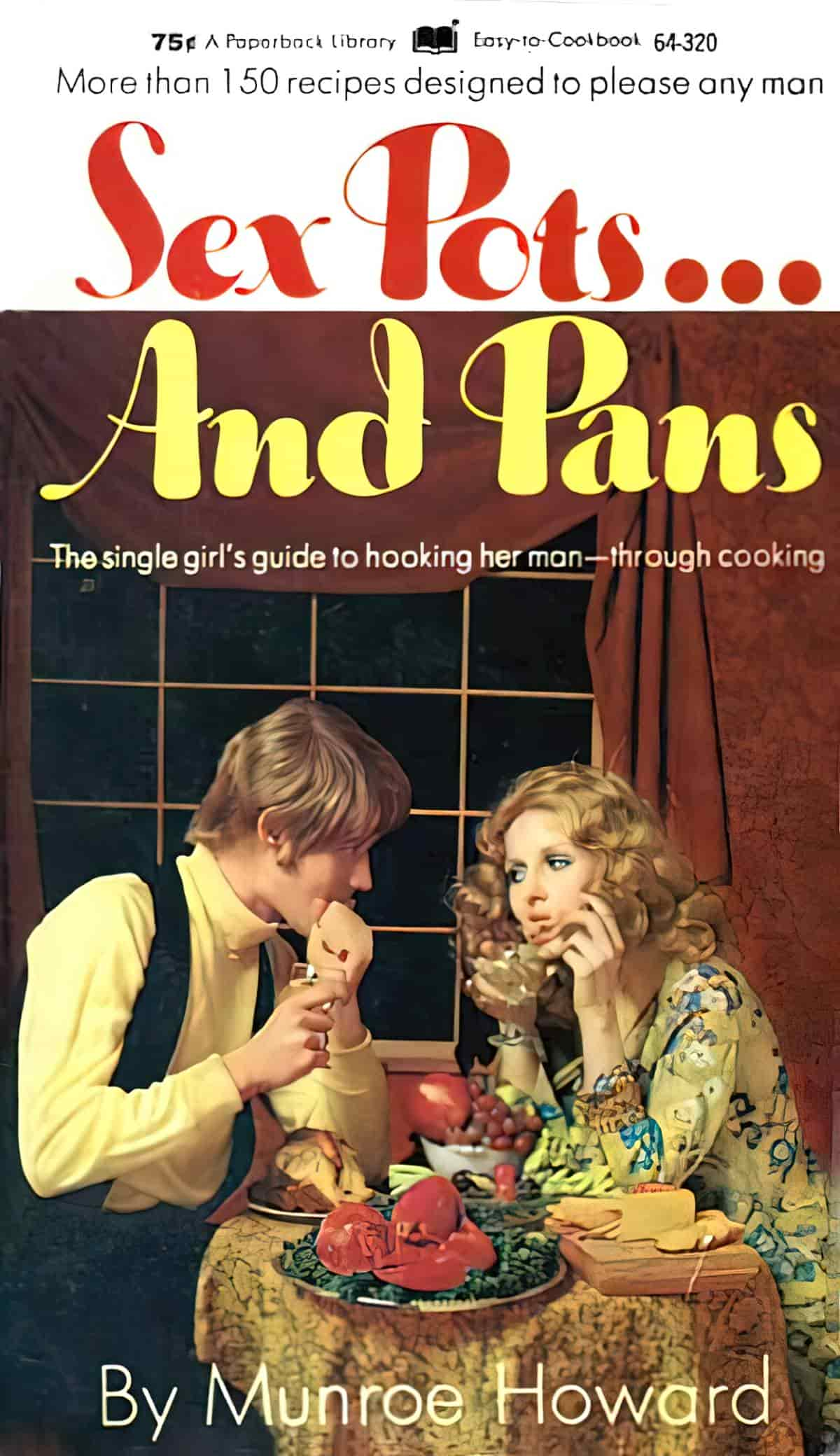

The Politics of Cook Books

COOKBOOK POLITICS (2020)

Many of us have stacks of cookbooks on our shelves, which we look through for ideas and inspiration, or to transport us to distant places with different foods, smells, experiences, and sometimes memories of our visits.

Kennan Ferguson, Professor of Political Science at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, argues that there is more going on in those cookbooks than just recipes. In fact, Cookbook Politics (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020) traces a variety of politics through a myriad of different kinds of cookbooks. Ferguson came to this project in an effort to try to understand where politics interacts with our everyday experiences.

Cooking and seeking out recipes to guide our cooking is a very common experience that many of us pursue. At the same time, the compilation of recipes into a book—published with glossy photos, or copied and stapled in a church basement—creates a space where there is inclusion and exclusion. Ferguson explores these dynamics in Cookbook Politics, coming to see how the culture and mores of a community are communicated through the cookbook as text.

Some of the earlier American cookbooks not only provided recipes, but also went so far as to instruct women on how to manage their servants, thus also highlighting economic and class dimensions embedded in the conveying of cooking instruction and domestic management. Other cookbooks convey a sense of the nation-state and can serve, in unexpected ways, as a form of international relations and diplomacy.

The most famous example of this is Julia Child, and how she served in an unofficial capacity as an American diplomat in bringing French cuisine and experiences to the United States. Ferguson devotes a chapter to examining the way that Child was able to shape the American imaginary of France in the post-war period, and how her cookbook also brings with it a discussion of Parisian manners and French disposition, while also noting that this relationship was interestingly one-sided, since Julia Child is not much known outside of the United States.

Ferguson also focuses attention on how we read and use cookbooks, not just in what they convey to us about nations, or regions, manners, or class, social position, and domesticity. Cookbook Politics asks us to consider what we do with our recipes, what we choose to omit, cross-out, or add in, and in so doing, we change the text, making it essentially a democratic text and format, where the person who engages the recipe may also alter it.

This is distinct from how we engage more traditional texts in political theory, which we may confront and argue with, but which we don’t usually alter to our liking the way we do with a recipe. Ferguson’s Cookbook Politics examines and analyzes the democratic dimensions of cookbooks, while also teaching us how we might read cookbooks to best grasp contextual politics, urging us to pay attention to what is being communicated in unexpected and often under-explored political theory texts.

New Books Network

Marvin Taylor, Director and Archivist of NYU Fales Library and Special Collections, has been instrumental in building one of the top culinary collections in the nations. He and Linda discuss the meaning of classic cookbooks and other archival materials that can help us piece together the past.

What Makes a Cookbook a Classic?

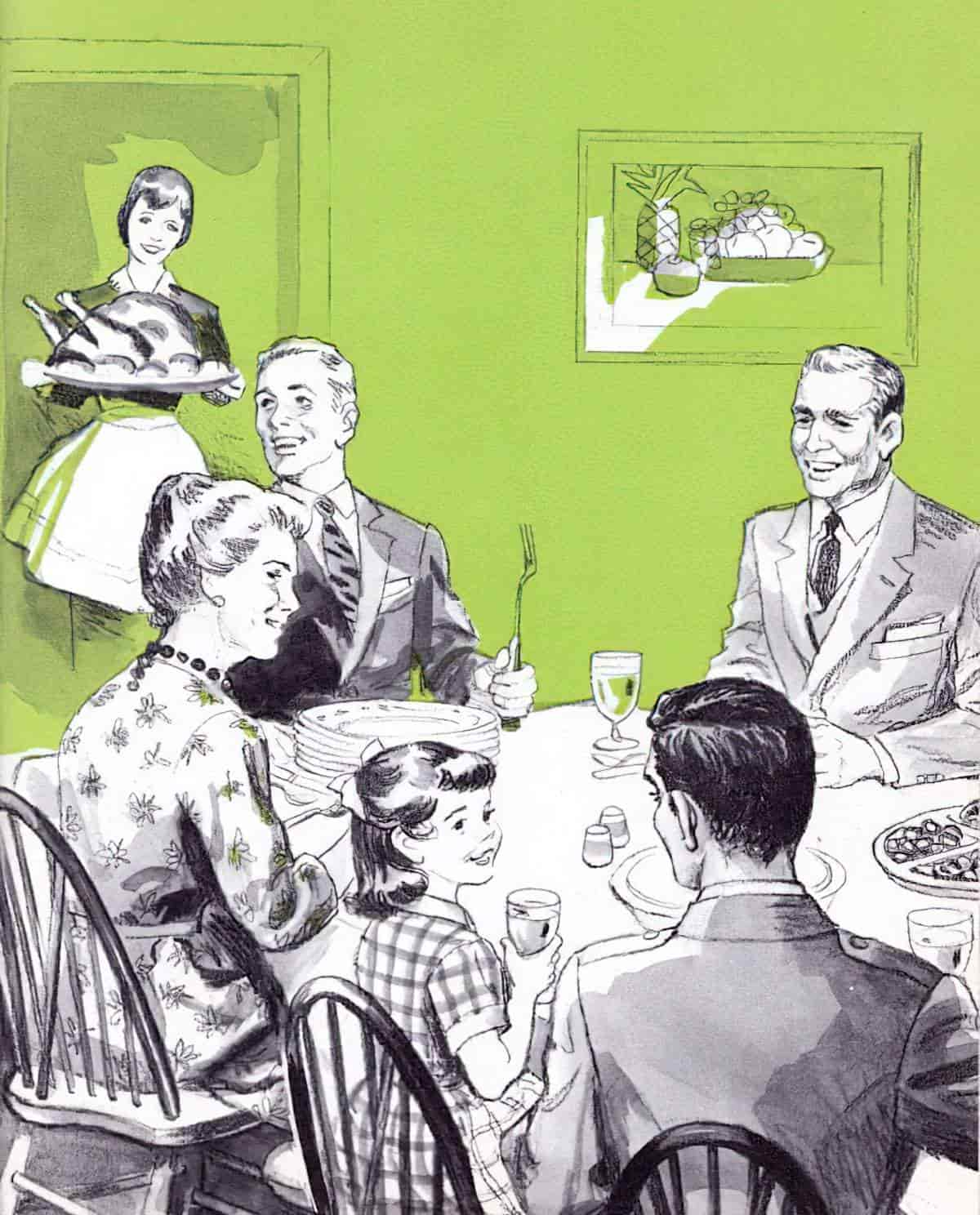

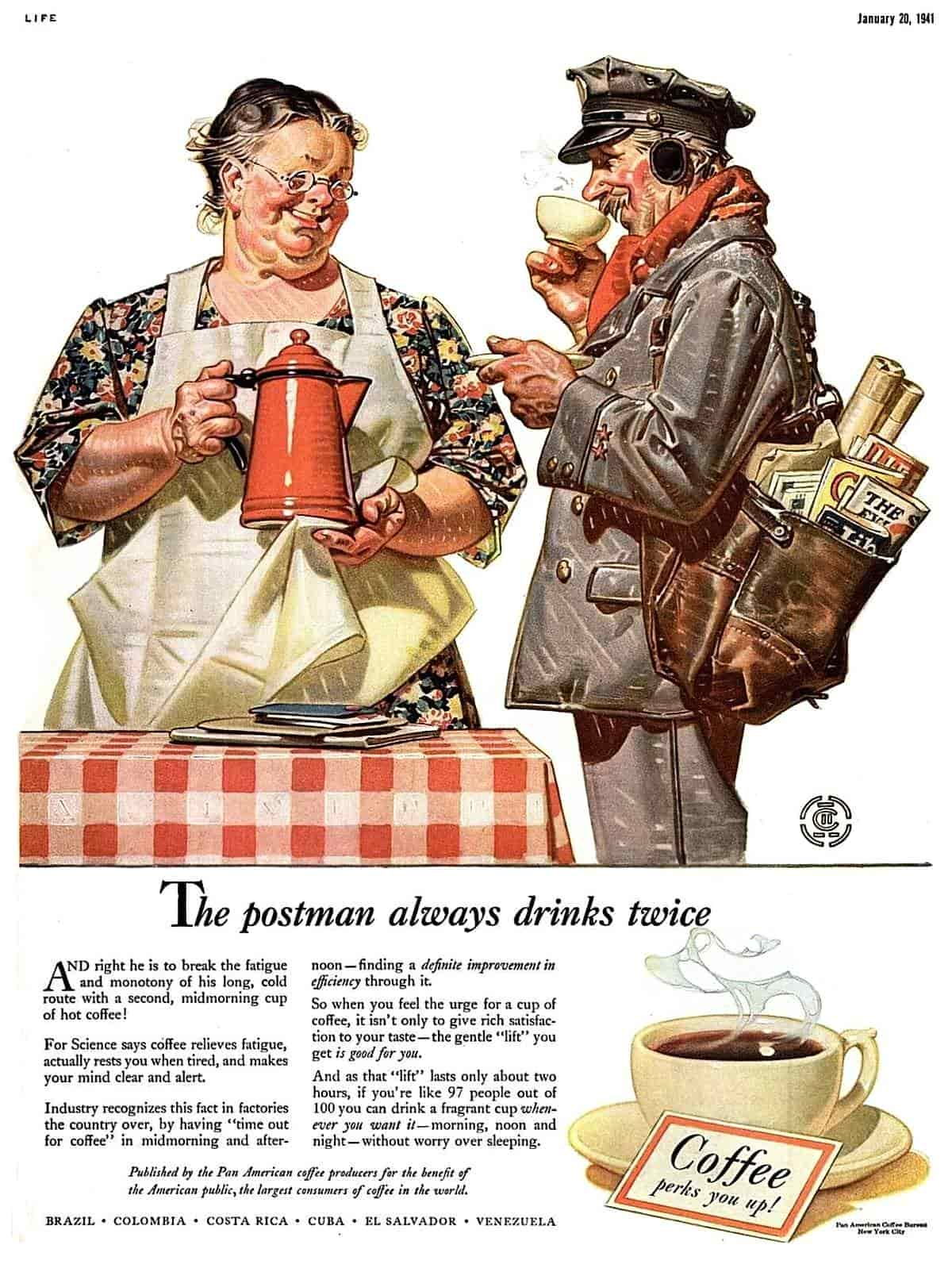

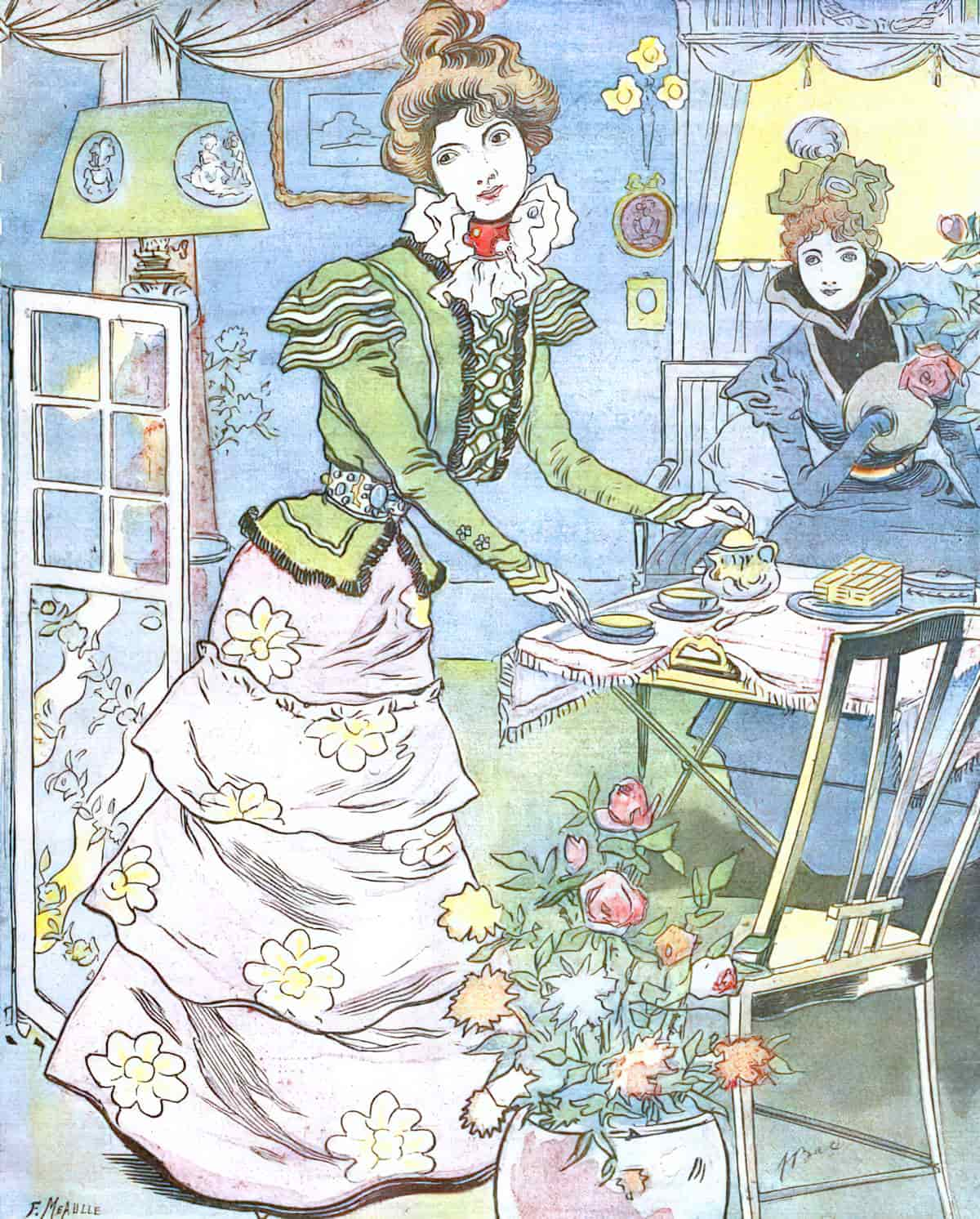

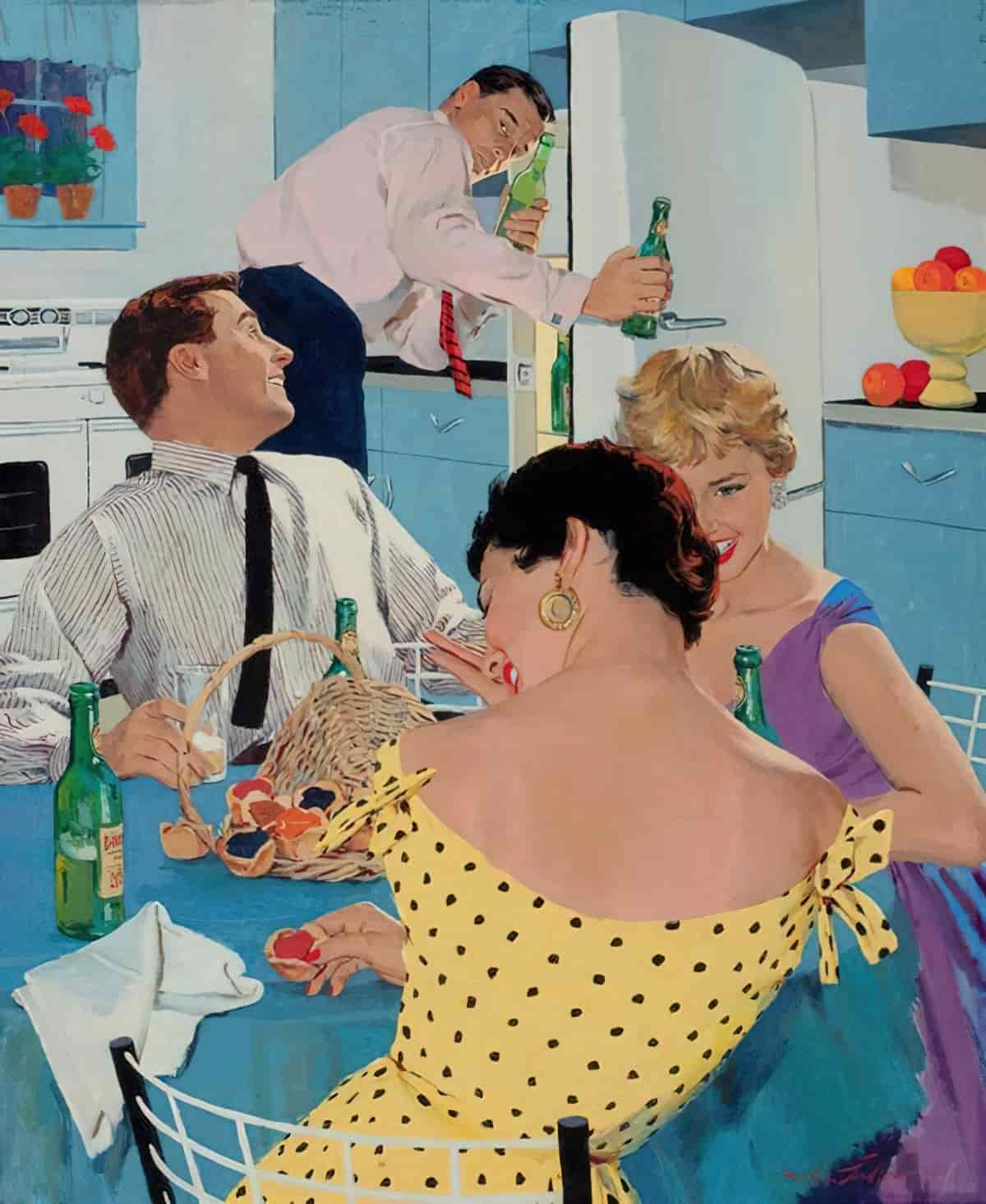

Women and Girls Serving Food and Drink in Art and Illustration

Although Margaret Atwood’s young character is not especially burdened by gendered expectations, most women her age were not so lucky. Even today, though sexism has decreased, misogyny is very much still in force:

“Rather, a woman is regarded as owing her human capacities to particular people, often men or his children within heterosexual relationships that also uphold white supremacy, and who are in turn deemed entitled to her services. This might be envisaged as the de facto legacy of coverture law—a woman’s being “spoken for” by her father, and afterward her husband, then son-in-law, and so on. And it is plausibly part of what makes women more broadly somebody’s mother, sister, daughter, grandmother: always somebody’s someone, and seldom her own person. But this is not because she’s not held to be a person at all, but rather because her personhood is held to be owed to others, in the form of service labor, love, and loyalty.”

Kate Manne, Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny

It is very rare to see anyone other than a woman or girl serve food and drink (except at high end restaurants, in which case it’s more prestigious to have a male waiter).