No one really knows why Harry Potter became so popular. In fact, many academics find Harry Potter relatively poorly executed, first from a storytelling perspective. Talking about another, better book, Diane Purkiss says the following:

There’s no info dump; there’s no narrator; there’s no Dumbledore figure who in the last chapter plods in and says ‘Harry, I’m going to tell you everything.’ None of that ever happens.

But there are also ideological concerns:

I find the determinism of the sorting hat quite troubling. The idea that you are a Slytherin, you are a Gryffindor. Especially when you’re eleven years old, for God’s sakes. Adults, too. Don’t you find it a bit worrying? It reminds me of Calvinist pre-destination, where from the beginning of time you’re destined to go to the hot place or not.

Diane Purkiss

I talk more about the Ideology of the Chosen One in this post.

Harry Potter Fans will of course say that the Harry Potter books sold widely because the books are excellent. But more widely-read specialists of children’s literature don’t accept this reason, because Harry Potter contains nothing that was really new or ground-breaking. Nothing that can be described, anyhow.

In his paper “The Phenomenon of Harry Potter, or Why All the Talk?”Jack Zipes has said that readers “know from beginning to end that Harry will triumph over evil, and this again may be one of the reasons that [J. K. Rowling’s] novels have achieved so much popularity” but this aspect is hardly limited to Harry Potter. Zipes actually criticizes this aspect of Rowling’s series.

Perhaps literature professors are not in the best place to explain Harry Potter’s success. Instead, perhaps this is a job for economists, mathematicians and philosophers.

Harry Potter is popular partly because of timing. In his book Black Swan, Nassim Nicholas Taleb talks about the concept of recursion, and explains that the world has been amassing an increasing number of feedback loops. People bought Harry Potter because other people bought it. Information flows very rapidly in modern society and a fast info society was a necessary prerequisite for the mega success of one series in particular, which probably could just as easily have been another one.

Regarding stories in general, nothing is unique, because everything rests upon the shoulders of what came before:

Readers often assume that each worthwhile story or poem is separate and unique, something that either emerges exclusively from one person’s individual creativity or has been inspired by forces beyond mere human knowledge—a “muse”, perhaps. And certainly, every interesting literary text does express the unique combination of cultural and other forces that make up the imagination of its writer. But writers have repertoires and work from their knowledge of previous texts just as much as readers do. The idea of a story about a detective figuring out which suspect committed a crime doesn’t occur independently to each person who writes a mystery novel. Most mystery writers have read many such texts before deciding to create their own.

The Pleasures Of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

TERRY PRATCHETT IS THE ANTI-ROWLING

The Harry Potter stories are good, solid stories (an ‘enjoyable romp’ according to Kirkus), and no better or worse than many similar tales that came before (and after) it.

Indeed, the stories share qualities with much other children’s fiction. Harry Potter himself is an orphan who, to begin with, lives with rigidly conventional people who are nasty to him—just as child heroes of children’s fiction have been orphaned and misunderstood throughout the history of children’s literature.

The tone of the Potter books, a blend of comedy and melodrama, share’s much with Dahl’s writing in Matilda and in books such as James and the Giant Peach and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. As stories set in a school, meanwhile, the Potter books reproduce the typical conventions of boarding school stories, particularly as represented in British boarding school stories from Thomas Hughes’s Tom Brown’s Schooldays to Frank Richards’s Billy Bunter series: characters of fairly stereotypical types and backgrounds indulging in hijinks, practical jokes, and sporting competitions.

In this case, the novels are fantasies rather than realistic fiction, and the school trains witches and wizards. But that also happens in Ursula Le Guin’s Wizard of Earthsea and Diana Wynne Jones’s Chrestomanci books. [I would add Jill Murphy’s Worst Witch stories.] Furthermore, many other fantasy series share the Potter books’ emphasis on characters maturing into a growing understanding of of their own powers and of the nature of good and evil through contact with unusual beings, not all of them human: not only Le Guin’s Earthsea books but also C.S. Lewis’s Narnia series, Susan Cooper’s Dark Is Rising series, Monica Hughes’s Isis series, and Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain series (which also shares some of the Potter books’ breezy comedy). Like these series, also, the Potter books seem to be heading toward a climactic confrontation between a young protagonist and someone or something powerful, adult, and intensely evil. [Nodelman and Reimer wrote this in the early 2000s — they were right!] Different versions of this plot operate in recent critical successes within the filed of children’s literature such as Philip Pullman’s Golden Compass and Lowry’s The Giver and Gathering Blue, and also in Katherine Applegate’s popular Animorphs series.

Note that the author of Animorphs is a supportive parent of a transgender child and that Ursula Le Guin’s thoughts on Harry Potter were before their time. She aired her thoughts anyway, despite pushback:

Nodelman and Reimer dismiss also the possibility that the Harry Potter books were expertly marketed, because in fact they were marketed no differently from any other book from the same publisher. They posit that the HP books are so successful precisely because they are a perfect blend of what has come before. Blending genres is the hardest thing to do. Perhaps what Rowling did was the children’s literature equivalent of this.

Jack Zipes is less impressed than many children’s literature critics with the Harry Potter series. In a critical essay on the first four Harry Potter books, Zipes expresses disappointment that so many people working in children’s literature today as critics and taste makers speak in glowing terms about the mediocre but nevertheless phenomenal series by Joanne Rowling without seeming to have read the books which came before and which, in some cases are superior works of literature.

WHAT TO READ ALONGSIDE HARRY POTTER

In Sticks and Stones, Zipes recommends the works of:

William Mayne — an English writer for children who is nonetheless notoriously under-read by children but read by adults. He published books between 1953 and 2009, but you may not have heard of any of them. You can still get your hands on A Swarm In May and a few others.

Joan Aiken — English writer specialising in supernatural fiction and children’s alternate history novels such as The Wolves of Willoughby Chase

Vocabulary on the first page of the Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aitken: pleated, eminence, wold, herring-bone, crenellated, hubbub, goffering, vigil. As a girl, I had no idea what most of these words meant and yet it still became one of my favorite books.

Susan Van Metre (@skeetermeeter), Jan 19, 2021

Rosemary Sutcliff — British author well known for historical retellings of myths and legends

Ursula LeGuin — American author well known for fantasy and science fiction works for children, for example the Earthsea series

Janni Howker — British author of fewer novels than the above writers, as well as short fiction

Diana Wynne Jones — See: How Diana Wynne Jones Changed My Life by Judith at Misrule.

“When I was a child, I would read absolutely anything. My favourite books for younger people would be I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith, which I really love, The Little White Horse by Elizabeth Goudge, all the classic children’s books. I love E Nesbit—I think she is great and I identify with the way that she writes. Her children are very real children and she was quite a groundbreaker in her day.”

Some of these authors you have probably heard of — others may be new. In any case, if you know of a reader suffering from Harry Potter withdrawal after reading the final volume, point them in the direction of his formidable ancestors.

The most influential children’s author over the past century is E. Nesbit. I list the reasons in this post.

David Beagley, La Trobe University, available on iTunes U

- How is high fantasy different from garden variety fantasy?

- Harry Potter (HP) has done huge things to this concept of fantasy and how it is delivered and practised in not just literature but in the broad areas of culture as well (movies, gaming and the impetus it’s given to other writers).

- Key readings: The International Companion Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature edited by Peter Hunt

- Also: The Heroic Tradition

- an article by Amy Green from The Looking Glass (an open access journal), about racial discrimination in Harry Potter

- High fantasy is not consistent with ‘accepted reality’. But who does the accepting? Who imagined what could be rather than examining what is?

- Kathryn Hume looks at this idea comparing two terms related to Tolkien’s idea of primary world and secondary world: mimesis (from mime, mimic, imitate) — the idea of sharing the reality that we have now, and comparing this idea to ‘fantasy’ in which you extend and alter that reality. Two worlds: one which is and one which could be.

- Dennis Butts looks at the difference between the ‘extraordinary’ and the ‘probable’. The probable refers to things which are credible — we think they not only can happen but are likely to happen. Mundane. (Mundus is the Latin, which means ‘the world’.) So mundane simply means ‘of this world’. Today it carries a negative connotation connected to ‘boring’. The extraordinary takes you away from that.

- The standard realistic adventure has the reader thinking ‘that could happen to me’. The fantasy has the reader thinking, ‘Yes, I can see me there.’

- High fantasy has nothing to do with the quality of the storytelling but is to do with the telling of the story. It’s to do with the scale of the story, the characters and the themes. The whole world is dependent upon the outcome.

- Take Watership Down and Mrs Frisby and Toy Story — the outcome of those stories mean absolutely nothing to us. But in Harry Potter and Star Wars the whole world is dependent upon what happens in the plot. This is what makes it ‘high’. [Here I was thinking it was all dependent upon the presence of a dragon.]

- Because we’re looking at the fate of the world then the good guys are very, very good. The bad are so bad.

- Because of the nature of the style of writing you also come across many allusions to other writing. Other writers may not appear directly but certainly influence what’s going on.

- The high fantasy worlds: Good vs evil worlds implies there are statements being made about humanity, about where humans fit into things. There are ethical concerns. (And Pamela Gates calls it Ethical Fantasy for this reason.)

- Recurring themes and motives in high fantasy: Ideals of black and white, symbology reinforces that binary. They usually take place outside our primary world.

- Of course the moral judgements derive from our world.

- Types of high fantasy: Quest. Often the main character has something about them that is really different. We get into quasi-religious judgements. For example Frodo/Luke Skywalker/Harry Potter all face what is effectively the Christ situation of ‘I am prepared to offer myself to die if the others can live.’ [I suppose this makes The Bible high fantasy.]

Harry Potter

- JK Rowling was born in Chipping Sodbury. [Yes, that’s an actual place.]

- Rowling had the entire series worked out before the first was published.

- It was thought that boys would resist an author called ‘Joanne’ which is why her name was shortened to initials.

- The story starts as a story for 11 year olds and is meant to finish as a near-adult story. This style was intended right from the start.

- A criticism: A couple of the middle ones (Phoenix, Half Blood Prince) could have been more carefully pruned and could have been half the length were she not so famous.

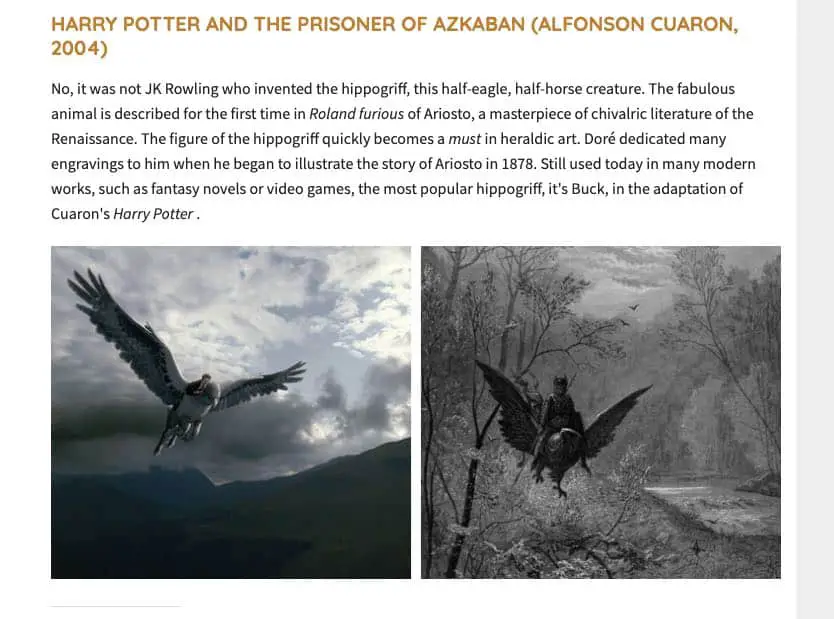

- One of the key things about HP is how heavily the plots draw on established ideas (witches, centaurs, goblins) but not just from that sort of thing but also from very specific characters. In Philosopher’s Stone Nicholas Flamel was a real person.

- Rowling comes up with marvellous allegorical names, which give a sense of goodness or evil e.g. Draco Malfoy (malodorous, malicious, dragons). Dickens is the one who came up with this onomatopoeic way of describing a person through their name. Dickens contributes tremendously to Harry Potter.

- See James Washick called Oliver Twisted: The origins of Lord Voldemort in the Dickensian Orphan.

- Enid Blyton also has an influence on HP. ‘The Famous Five Go Off To Mallory Towers And Then Up The Faraway Tree’ might describe HP. Blyton was very good at the boarding school story. The chums who look out for each other in Famous Five are very much Ron and Hermione and Neville supporting Harry. The Faraway Tree’s type of magic is comic almost, developing as the story goes on, but at the start HP is just Magic Wishing Chair kind of stuff.

- Questions have been raised about censorship. HP is now one of the most challenged books in US libraries, where compared to England/Aus/NZ the public have a much greater capacity to challenge books used in schools. Consequently, teachers and school boards in USA are more ready to act at the slightest complaint. Some people don’t like HP because of the magic and occult. What is the role of magic in the story? Is magic a magic mechanism that solves problems, or is it simply a bit of decoration in the background — a tool among others? The other main problem regards the death and violence. Many characters die. Is it necessary for all these people to die? These are major characters who readers have developed sympathy with. Or is death purely there for video-game type entertainment?

- What is magic? It is certainly super-normal/paranormal/supernatural. Any sort of mechanism that appears beyond the understanding of the observer observes magic. Anne McCaffrey wrote a series of novels set in a world called Pern. Their duty was to get rid of a thing that flew past every 400 years. But as the stories developed across the series it turned out they were not anything magic but genetically engineered little wizards, and all the people living on the approaching world were originally from earth [or something]. So what appeared to be magic ended up being science. Eventually the whole thing is solved by blowing up the spaceship.

- What is the magic in HP? A devilish power or a fantasy tool to use?

- Look at the choices characters make rather than the tools used. This argument is used in wars. If we go out and kill are we as bad as the people opposing us? This same question comes up in HP, but is not answered.

Related:

Why fantasy is not just juvenile nonsense from The Telegraph

At io9, commenters ask why movies these days are all high stakes. What did we do to deserve that story to the exclusion of all others? (Purchased box office tickets, I guess.)

FURTHER READING

6 Baffling Attempts to Ride Harry Potter’s Coattails

15 Books As Enchanting As Harry Potter from Julia Seales

Witch, Please is a fortnightly podcast about the Harry Potter world by two lady scholars

What Makes a Book, Song or Movie Popular? A Conversation with Noah Askin

Parents have always turned to books they know for their children, but she also believes Harry Potter started a new era of “collective reading”: “The notion of being a private reader with your own book was completely turned on its head.” This is good in some ways, she thinks, but it means “publishers can’t resist publishing celebrities, because half the work is done for them. Some celebrities do write good books – but you have to hope it’s a stepping stone to other things and often, it isn’t.”

Famous first words: how celebrities made their way on to children’s bookshelves

In this conversation (one of my favorite interviews ever), I talk with Noah Askin of the University of California at Irvine about why some popular children’s books, songs, and movies seem to last forever. Is it because the successful ones are similar but different? Is it a fluke? Is it the marketing? Or is it the story that the song/book/movie/anything tells, or is, or is it perhaps the story we make of it.

Noah Askin is Assistant Professor of Teaching Organization and Management at UC-Irvine in the Paul Merage School of Business. Prior to his arrival in Southern California, he was an Assistant Professor of Organizational Behavior at INSEAD, where he directed and taught multiple Executive Education programs in addition to teaching the organizational design and leadership core course in the MBA program. He has a popular TEDx talk on what makes popular songs succeed.

Mel Rosenberg is a professor emeritus of microbiology (Tel Aviv University, emeritus) who fell in love with children’s books as a small child and now writes his own. He is co-founder of Ourboox, a web platform with some 240,000 ebooks that allows anyone to create and share flipbooks comprising text, pictures and videos.

New Books Network

The Dark Fantastic: Race and the Imagination from Harry Potter to the Hunger Games

Ebony Elizabeth Thomas has written a beautiful, captivating, and thoughtful book about the idea of our imaginations, especially our cultural imaginations, and the images and concepts that we all consume, especially as young readers and audience members. The Dark Fantastic: Race and the Imagination from Harry Potter to the Hunger Games (NYU Press, 2019) dives into the question of, as Thomas explains, “why magical stories are written for some people and not for others.” Thomas explores the narratives of magical and fantastical stories, especially ones that currently dominate our Anglo-American cultural landscape, and discerns a kind of “imagination gap” in so many of these literary and visual artifacts. The Dark Fantastic provides a framework to consider this imagination gap, by braiding together scholarship from across a variety of disciplines to think about this space within literature and visual popular culture. Thomas theorizes a tool to examine many of these narratives, the cycle through which to contextualize the Dark Other within these fantastical narratives, noting that the Dark Other is the “engine that drives the fantastic.” The Dark Fantastic spends time analyzing and interrogating a variety of televisual and cinematic artifacts, noting how the Dark Other cycle operates in each of these narratives. In exploring these narratives, and considering who the protagonist is in so many cultural artifacts, the imagination gap becomes not only obvious but quite distinct. Thomas is concerned about this gap, because of the implication it has for readers and for film and television viewers—not only in regard to representation, but also in terms of learning how to imagine, how to dream, how to think conceptually, and how to center one’s self within these fictional spaces and created worlds.

New Books Network

rowling’s understanding of class is sub ‘a christmas carol,’ written 150 years prior, which at the least identifies the rich’s actions and affluence as the cause of the poverty of others. she never gets even there

i’ve recently read a lot of her non-HP writing. rowling considers poverty to be a fact of the world, unaddressable on a systemic level, and anyone proposing to do so is either an ignorant busybody or a scheming liar. it exists as window dressing, not to be fixed

the special few can rise, or be lifted, out of poverty, by virtue of their specialness. its only other function is to sort characters into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ depending on their opinions about it. good = maintain the status quo, & bad = systemic change of any kind, for any reason

@shaun_vids 4:10 AM · Jan 9, 2022

It’s never been fully explained why there is even poverty in the Wizard World, given that they all have free schooling, healthcare, and the ability to replicate any resources with a flick of the wrist. Why is the weasley’s house so shit like just use magic to make a better house?

@ctingstrange