**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

Wanna go out this Saturday?

Let’s read a story at home instead.

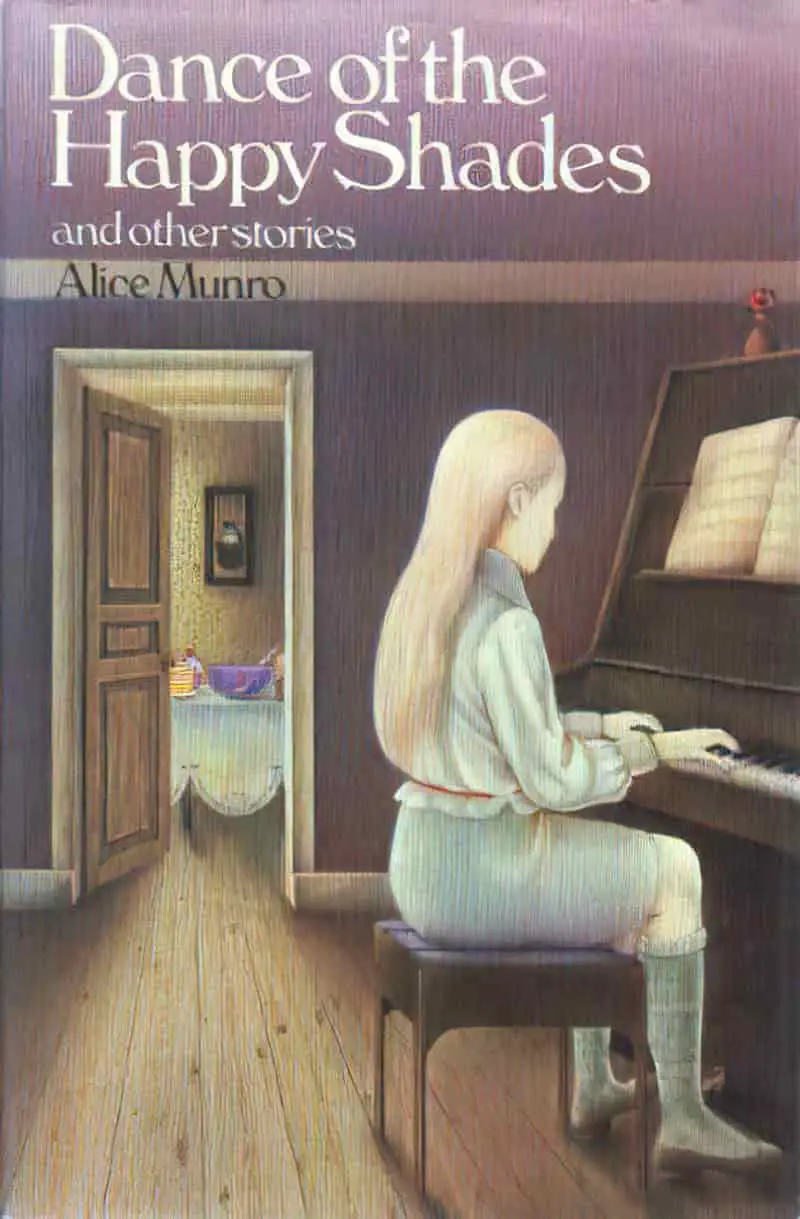

“Thanks For The Ride” is a short story by Canadian author Alice Munro. Find it in Dance of the Happy Shades (1968). “Ride” has two meanings in this one. Yes, those two meanings.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THANKS FOR THE RIDE”

SETTING

- 1960s

- small-town southeastern Ontario

- a fictional town called Mission Creek

- population 1700

- a tourist town: “Gateway to The Bruce” (now linguistically reclaimed as Saugeen Peninsula)

- with two young men sitting in a shabby eatery called ‘Pop’s Cafe’

- next to one of the numerous lakes around there

- Saturday night

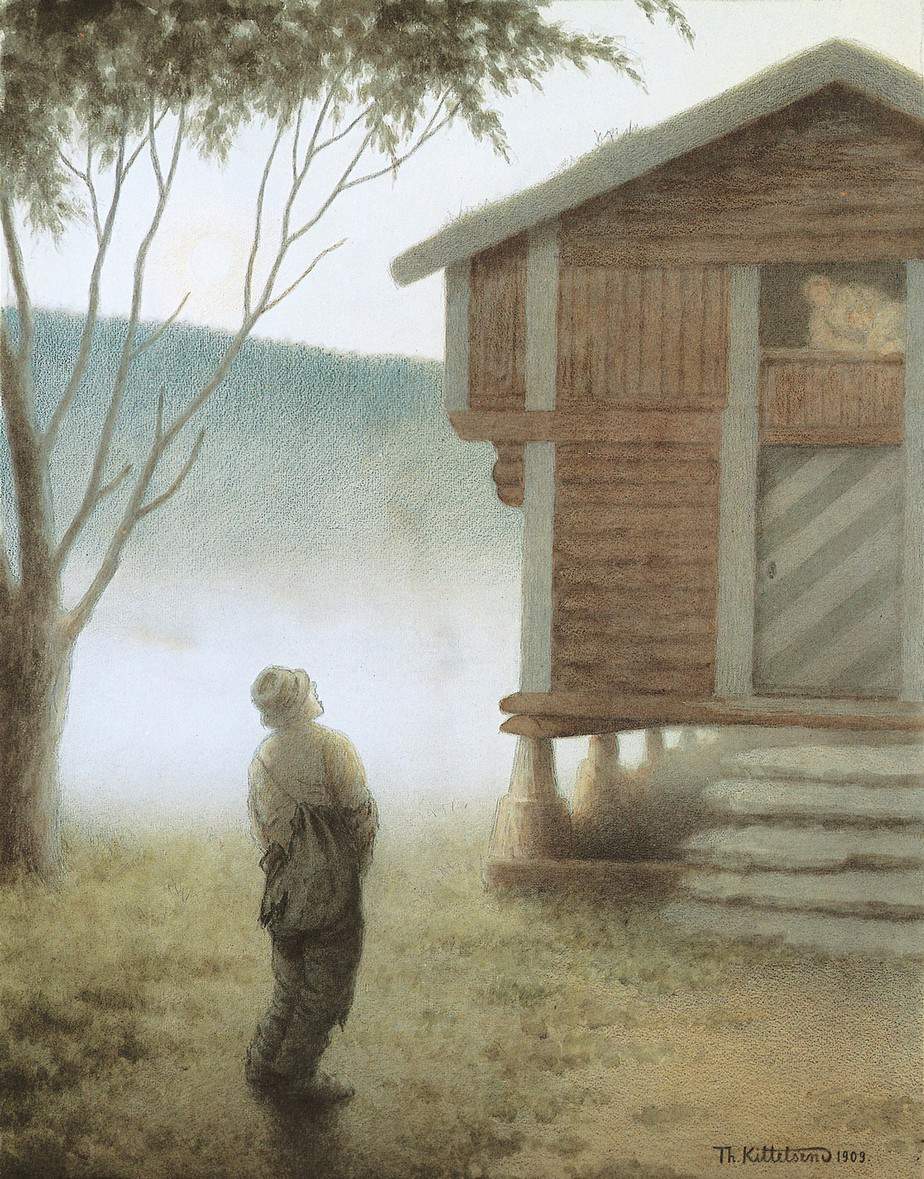

- late summer (symbolically important: a liminal season, also a liminal age, when boys become men)

- evening (double liminality!)

“This summer.”

“It’s last summer now.”

“Thanks for the Ride”

THE NARRATOR: DICK/DICKIE/OLD DICK

Note that Alice Munro uses both the diminutive and the old-man version of Richard’s name as he uncomfortably straddles two worlds of boyhood and manhood.

Alice Munro mostly writes about the lives of girls and women (hell, that’s even the name of one of her collections) but she does occasionally write about men and boys. (See, for example, “The Love of a Good Woman“, reminiscent of Stand by Me.)

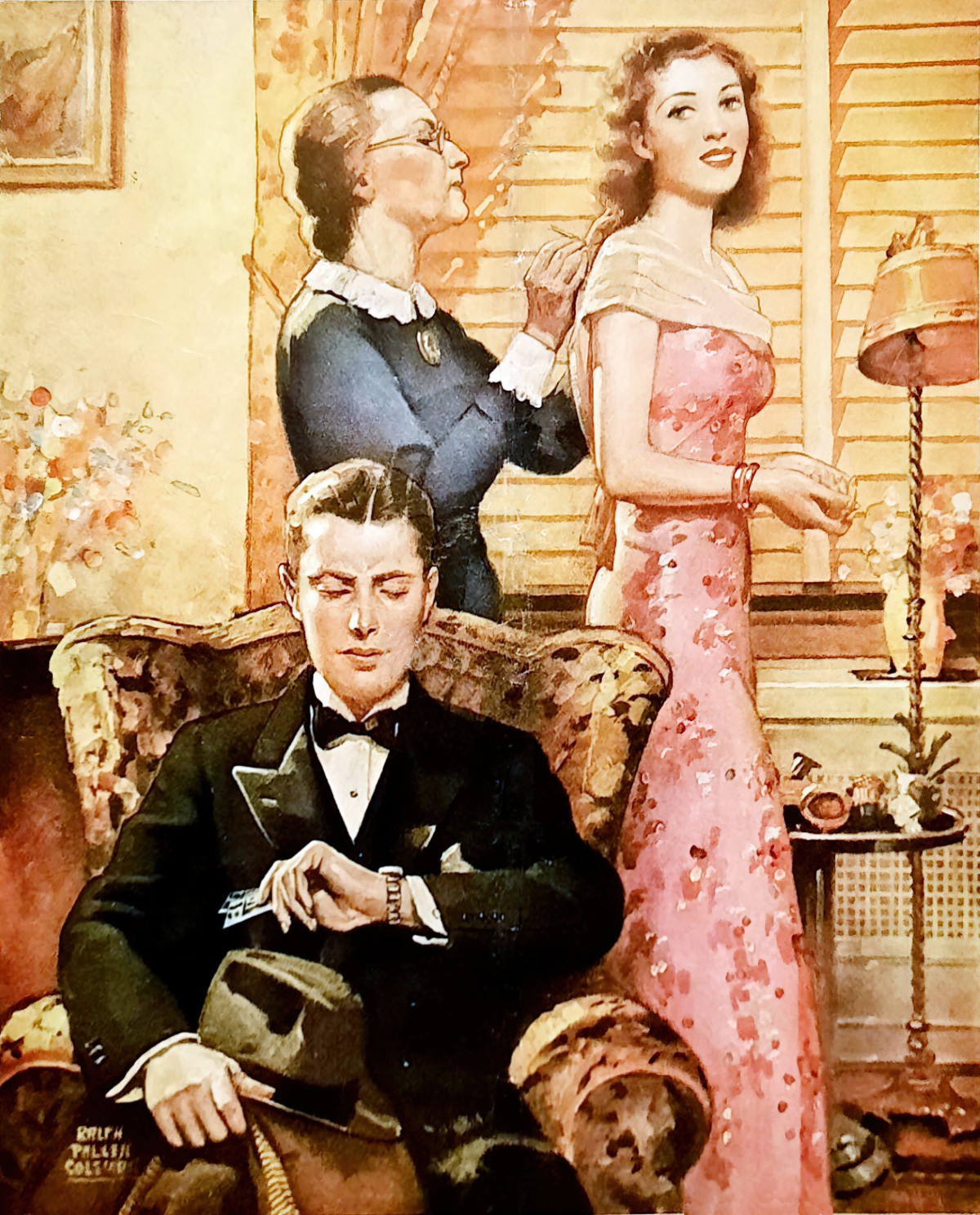

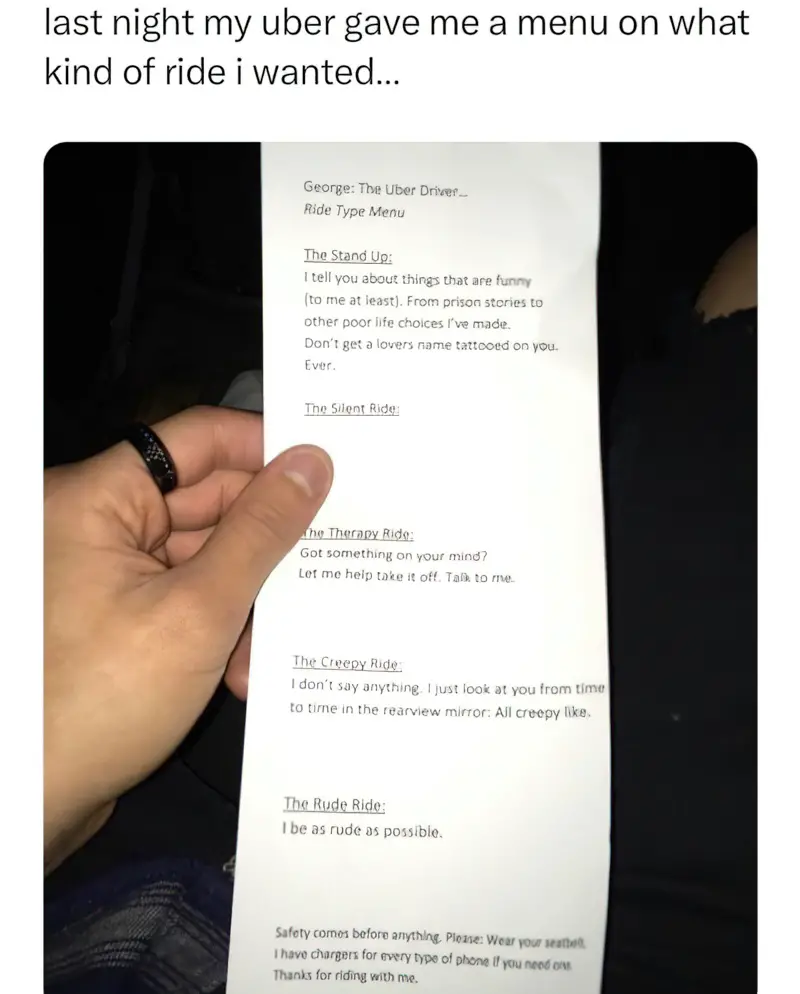

The narrator of “Thanks for the Ride” is an 18-year-old man. He’s out with an older male mentor, his cousin George. They’re on the prowl. The slightly older man is teaching our guy to pick up girls. Get virginity out of the way, enter true manhood. We live (have always lived) in a culture of compulsory sexuality, where legitimate, rounded adulthood requires marriage, sex and children. And for men, adulthood means partnered sexual experience, then marriage and children. This leaves a demographic problem: If young women are supposed to wait until marriage, who are these young men supposed to be having unmarried sex with?

Loose girls. Passably pretty but worthless girls. Girls no self-respecting man would never, ever marry, unless he were silly enough to fall in love with her. There’s no danger of love when you venture to a different town, where you know literally nothing and no one, not even the best place to eat.

THE OPENING PARAGRAPH

The opening paragraph conveys this via foreshadowing: The narrator and his cousin are eating at a dive with substandard food, conveyed by the detail about the fly specks. According to George, if these two knew the town, they wouldn’t be eating at Pop’s.

Rather than ‘foreshadowing’, you might find the term objective correlative useful to describe Munro’s opening literary trick:

Objective correlative: a means of revealing the emotional content of one subject while discussing another. It distances the emotion and prevents sentimentality.

The opening paragraph is the entire story in a snapshot. The narrator’s meal in a fly-specked down-and-out cafe becomes the object correlative for an empty and meaningless sexual experience.

As a compare and contrast, have a look at my post on the objective correlative, in which a 1983 paper explains the concept of objective correlative by means of a Johnny Paycheck song called “Drinking and Driving”:

the singer’s purchase of gas and alcohol becomes the objective correlative for a lost love and a meaningless life.

Tammy Wynette and the Objective Correlative by George William Koon, 1983, Studies in Popular Culture

In Alice Munro’s story, as in Johnny Paycheck’s popular country music, male narrators tell us one thing (here: a disappointing night on the town, starting with a shltty café) while really telling us about something else (an emotionally bereft first sexual encounter).

“What a dump! Jesus, what a dump!”

George, talking about the small tourist town, while feeling insecure about his manhood, shown by his lacking money and his own car — two other symbols of manhood.

WHY MIGHT ALICE MUNRO MAKE USE OF THE OBJECTIVE CORRELATIVE?

- To create a unified thread of emotion. First person narration works well with the objective correlative, but isn’t requisite. The objective correlative helps readers see how a narrator (first person or otherwise) is emotionally detached from their experience. Detachment is super important to this story, because Alice Munro is exploring the cultural forces which require emotional detachment from sex, especially virgin-busting sex for young men as compulsory rite of passage.

- All good stories contain irony. One irony is illuminated in the opening paragraph as George reads from a sign: “We love our children.” (Why farm the girls out to to sex tourists, then?) The objective correlative can help illuminate further ironies. Tonight is supposed to be about the beginning of manhood. But it’s also (really) about the end of an eighteen-year-old boy’s childhood innocence. Nothing really got started here. Without Dick’s full, unpressured consent, was it even really ‘sex’?

- The objective correlative makes difficult emotions (and topics) palatable. It also helps authors avoid moralising. When Alice Munro ‘lays out the evening’ she is not simply laying it out. She is definitely guiding us. I doubt we’re supposed to come away from this story thinking, “Okay, so that was a young man on a fun night out.”

GEORGE

As far as George is concerned, the food in this town doesn’t pass muster and neither do the girls they’re about to pick up. Yet here he is, consuming whatever he and his younger cousin can get their hands on.

Note that Dick doesn’t mind the food or the town. He’s not complaining about the place like George is. This difference in attitude about the town will map onto how George dismisses the girls. George is teaching his younger cousin to dismiss disposable girls from other towns. He is teaching his cousin to Other them. This little sex escapade can’t happen unless this macho emotional preparation takes place first.

DEFAMILIARIZATION

I’ve already talked about the objective correlative—one tool in a large toolbox of other tools which writers use to make the familiar seem striking. (Modernist writing makes much use of this toolbox.)

A tourist town is the perfect setting for a defamiliarizing experience. Readers will recognise the experience of driving to a new town which is basically familiar (the same kinds of shops on the main street; the same chain stores in the local mall etc., or in this story, the town hall with its bell tower, the memorial to soldiers who died during the war) but just different enough to be unsettling, or unheimlich (un-home-like). Taking that idea further: Sex at its best feels like coming home, but sex under social coercion has the appearance of coming home, but feels nothing at all like it.

I put my arm around her, not much wanting to.

“Thanks for the Ride”

See: Unwanted Sex and Nonconsensual Sex are Not the Same Thing by Justin Lehmiller’s blog. Alice Munro’s short story “Thanks For the Ride” encapsulates perfectly how for a young man in Dick’s position wants sex but doesn’t consent to this particular form of it. (Or perhaps you could argue that he consents to it but doesn’t want it? Which do you think it is?)

See also: “Consensualish”– What about sex that is unwanted, but not physically coercive? || Jessie V. Ford and 71% of UK men have experienced some form of sexual victimization by a woman (a small study which has its limits)

As George and the other girl, Adelaide, get it on, Dick is left thinking he should be further into ‘the stages’ than simply putting an arm around a girl. He has a clear idea of what those stages entail, despite sexual inexperience. This is another cultural script known to everyone very early. We frequently hear sports metaphors (first base, second base and so on). But the linear progression of sex is itself a problematic concept which has only recently attracted criticism, and still has a long way to go. The key is to understand all the ways sex can look (in the 1990s, Bill Clinton tried to gaslight everyone into thinking that certain types of sex are not sex). Critique of “p in v” sex as the Gold Standard requires an understanding of queer sex and non-normative bodies.

Ultimately, Dick’s first sexual experience is heartless, discombobulating and defamiliarizing. The town is unfamiliar; the sexual (or sexualized) experience defamiliarizes. Sure, he’ll have shucked off his childish status as virgin, to enter a new life as a fully-fledged Man, but he’ll be knocked for six in a disturbingly run-of-the-mill way.

That’s why we don’t know much about these young men. Munro keeps them as archetypes of young men out on the prowl. They remain depersonalised to themselves, to the girls and also to us. Readers learn more about the backgrounds of the young women they pick up, especially Lois, which shows us that Dick does not actually want to depersonalise his date. He wants to talk to her, and is astute enough to understand that, for Lois, sex is less personal than talking.

By the way, depersonalisation means something slightly different in the field of psychology: a state in which one’s thoughts and feelings seem unreal or not to belong to oneself. I believe Alice Munro is utilising both (writerly and psychological) senses of this concept.

SEXUAL MORALITY

Making use of the writing techniques listed above, Alice Munro avoids coming down morally on the rightness or wrongness of what these young people are up to on this summer evening. Instead, she lays out a scenario, includes sufficient detail to describe it as if readers were there, then leaves us to form our own opinions on it. Was it really fun? What was really achieved here? What are the social forces which lead young people to behave in this way, whether they are young men or young women? We help write the story. Alice Munro is our guide.

THE 1960S SEXUAL REVOLUTION

Remember, this was written for a 1960s audience. By the end of the 1960s, there was increasing pressure on young women, as well as on young men, to ‘liberate’ themselves by having sex. Recreational, unattached sex without the looming threat of unwanted pregnancy was technically possible for the first time in history. With it came new pressures for women, which aren’t so different from pressures today. We are currently undergoing another sexual revolution. In order to be a Good Feminist, a Western woman is required to seek frequent and satisfying sex. Share those experiences with female friends to deepen friendship bonds. Otherwise, FOMO. Low-level but very real social ostracization.

As Amia Srinivasan says in The Right To Sex:

Sex is no longer morally problematic or unproblematic: it is instead merely wanted or unwanted. In this sense, the norms of sex are like the norms of capitalist free exchange. What matters is not what conditions give rise to the dynamics of supply and demand—why some people need to sell their labour while others buy it—but only that both buyer and sellers have agreed to the transfer.

“The Right To Sex” in The Right to Sex by Amia Srinivasan (2021)

Srinivasan argues that it’s time to critique this binary (unwanted/wanted), and also that it’s time to ask questions about all the wider cultural forces which give rise to desires.

Why do we choose what we choose? What would we choose if we had a real choice?

“The Right To Sex” in The Right to Sex by Amia Srinivasan (2021)

A big message of Srinivasan’s book which applies to contemporary, 2020s Western sexual culture: The absence of consent isn’t the only indicator of problematic sex. Sex can be consensual but also systemically damaging.

The purpose of a system is what it does (POSIWID) is a systems thinking heuristic coined by Stafford Beer, who observed that there is “no point in claiming that the purpose of a system is to do what it constantly fails to do.”

The purpose of a system is what it does

Perhaps my favourite line from Srinivasan’s book (I have many favourites): A critique of Rebecca Solnit’s comparison between the ‘right’ to having sex and the ‘right’ to share someone’s sandwich:

Sex isn’t a sandwich, and it isn’t really like anything else either. There is nothing else so riven with politics and yet so inviolably personal. For better or for worse, we must find a way to take sex on its own terms.

“The Right To Sex” in The Right to Sex by Amia Srinivasan (2021)

It is true; whatever we say about sex cannot be compared to anything else. No metaphor, no simile works, because sex is its own thing. And it is not enough, surely, to approach this 1960s short story with a 2020s view which says: These young women knew what they were doing, were clearly getting something out of it themselves or else they wouldn’t have been doing it.

THE GIRLS

After meeting two young women, remarkably easily, Dick wonders why on earth the girl called Lois would take them home to meet her family. She hasn’t even looked him in the eye. Is this a deliberate attempt to make him uncomfortable? Doesn’t she know the four of them only want sex?

Let’s go through the possibilities.

- That Dick is correct. Lois is putting Dick through his paces. Sure, she’ll have sex with him, but he’ll pay his dues by meeting her mother and grandmother first. Before she disrobes, she’ll show him the circumstances of her family: financially precarious.

- That she simply wanted to change into a nicer dress.

- That Lois, like the young men, has learnt a social script around sex. For Dick and George the script is this: Lose your virginity in a different town where the girl doesn’t matter. For Lois and Adelaide: If you’re thinking of having sex, bring the boys home to meet your mother first.

But while Lois is changing into her yellow dress, Alice Munro shows the reader why this mother and grandmother are content to let their daughter go out for sex with boys they have literally only just met. The mother is quizzing Dick mercilessly about his family’s social and financial status. He passes muster. It starts with the car. Dick has a patriarch at home, a chartered accountant. Tick and tick. The mother’s line of questioning reveals that she understands a grim reality: Her daughter’s best chance at improving her lot in life is to marry a man from a privileged family. This is a family of women. The husband was killed in a gruesome accident, which the mother recites to Dick with the detached emotion of someone who was once traumatised, but who has become distant from the experience via repetition. So it is with sex. Sex is transactional, here. If Lois is able to marry this young man with the nice car, all three women will be looked after.

The old woman, perhaps in the throes of dementia, tells Dick he can do what he likes with her grand-daughter, so long as he doesn’t get her pregnant.

This is the Old People Speak Truth trope. (As do young children, e.g. in “The Emperor’s New Clothes“.) But which part of the observation does the mother feel should have been kept within the family? The part about Lois having sex, or the part about not getting Lois pregnant? Perhaps getting pregnant is part of the trap? Surely, in a small town like this, the mother understands these boys are just passing through. Ultimately, we are left to wonder about her motivations, as is Dick. Because without talking to her—prohibited according to the script—it is impossible to know what she wants.

But we can see the cultural forces at play in the life of this sixteen-year-old girl, who has been ‘allowed’ to legally quit school two years before rich kids because her father died and the government accepts that she needs to help her mother and grandmother financially. Rather than provide poor families with the means to live, instead we ‘allow’ children to miss out on education. (And just when the West might’ve thought we were beyond this, ten USA states are in 2023 trying to weaken child labour laws, and not because this is good for the children.)

Why has she used her hard-won money to buy an imitation cashmere sweater and a fur coat? Because, like the dress, it is her ticket to access upper-class boys. It’s an investment.

THE SLAP

Lois slaps Dick when he repeats something Lois’s mother said to him earlier, in what the reader knows to be an unintentional parody. Unintentional because he’s all at sea in this entire scenario and he’s been making use of scripts the entire time. Borrowing the words of the mother is yet another use of script.

But how does it come across to Lois, who is being pimped out to boys for sex in the vain hope that sex will turn into marriage? It sounds like the boy is on the mother’s side, in on the mother’s plan and as knowing as Lois is. In the moment, he is not. Only after the hindsight of writing this first person story would he have become aware of how events fit together.

For Lois, sex and enmity are a more comfortable fit than sex and friendship, because that is what is familiar to her by now. Once enmity is established, sex can take place. Neither party is under any illusion. Finally, some honesty.

More cynically, it is easier for Lois to associate sex and men with violence because that is her lot in life. We are attracted to what we find familiar.

OMNE ANIMAL

Alice Munro doesn’t take readers into the barn with Lois and Dick and doesn’t need to.

Afterwards, driving the girls back into town, Dick would like to tell Lois about omne animal, but feels his knowledge of Latin would feel like he’s being a show off, even though he’s sure Lois would know exactly what he meant.

What does he mean? (What does Alice Munro mean by including it?) The full saying:

Triste est omne animal post coitum, præter mulierem gallumque.

Every animal is sad after coitus except the human female and the rooster.

This young man thinks Lois has got what she wants, whereas he has not. Dick remains sad. Rather, he is sad now when he wasn’t before. This story is a tragedy. But is he right about Lois? Nothing in her pretend-sleep suggests she is any less sad than he is. The sadness of Lois is a permanent state, and by contrast, a brief sexual encounter may afford temporary relief.

THAT HEADLONG JOURNEY

Dick has revealed to us that he thinks sex is a linear series of actions and events, working his way through the bases. We all know how that goes. But as Shere Hite noted in her controversial landmark book about female desire—in comparison to the men in her studies, women were nowhere near as pressured to perform as the men. For men, this ‘headlong journey’ seemed like work.

The car journey back into town is another objective correlative (for unsatisfying, scripted, young-male coitus, because ‘sex’ is not the right word). To underscore this connection: the pun in the title, of course.

CIRCULAR/LINEAR (FEMININE/MASCULINE)

Munro opened with an object correlative, and now she closes with another. The story itself is circular, when the central act was linear, building to a disappointing climax. If acceptable feminine culture is all about circularity (menstruation, childbirth, continuing the cycle of life yadda yadda), and acceptable masculine culture is all about linearity (leaving home, venturing on a journey, having a firm plan, making one’s way towards a battle) then Dick has just shown us that there’s something of the feminine in him. He didn’t want that headlong journey in the car back into town to be so ‘linear’. He wanted to talk. He wanted connection, the connection of joining together, really joining together, as in a feminine, forbidden circle.

FURTHER READING

Neil Gaiman wrote a story about the sexual coercion of teenage boys in his short story “How To Talk To Girls At Parties”. In Gaiman’s spec-fic story, the girls are literal aliens.

**UPDATE LATE 2024**

Neil Gaiman is yet another powerful abuser.

If this is news to you and you’re skeptical, here is a link roundup.

Tortoise was the first (semi) mainstream outlet to give voice to one of Gaiman’s victims. Unfortunately, Tortoise is funded and owned by a notorious anti-trans bigot, so even though I listened to the series and the individuals involved did a great job, I don’t want to help promote bigotry.

OTHER STORIES IN DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES (1968)

- “Walker Brothers Cowboy” — A woman looks back at her 1930s childhood. Her family has 2 or 3 months earlier lost the family fox farm and moved to a small town on the edge of Lake Huron, where the father has started a new job as a door-to-door salesman. Meanwhile, the mother sinks into a depressive state. One day, the father takes the narrator and her younger brother on a ride, where he visits an old friend/lover. The daughter learns that her father had another sort of life once.

- “The Shining Houses” — In a new neighbourhood, many houses have been built next to an old one. The owner of the older house, Mrs. Fullerton, does not take care of her property to the extent that the owners of the new houses would like. They conspire to get rid of the old poultry-farming witch. Only our narrator seems conflicted.

- “Images” — A little girl is the narrator of this double character study: A second cousin who came to take care of the household while her own mother was sick, and a man with a psychotic mental illness who lived alone in the woods. After meeting the man in the woods, the little girl learns not to be afraid of the woman who has infiltrated the household to take care of them all.

- “Thanks for the Ride“

- “The Office” — A housewife decides to improve her life by carving out some time for herself to pursue her passion of writing. So she rents a room above a hair salon and drugstore. But the landlord won’t leave her in peace, deeming her time his.

- “An Ounce of Cure” — A young teenager is pining after a boy who dumped her months ago for another girl. She can barely think of anything else. One night she is babysitting when she spies three bottles of liquor on the bench. She accidentally gets very drunk and very caught out. Her reputation is ruined. But as an older woman looking back on this time, she is glad it happened.

- “The Time of Death” — A mother who lives in one of the squalid cottages on the edge of town has lost a child in a terrible accident. The village gathers round, but how genuine are they in their grief?

- “Day of the Butterfly” — Two girls at a primary school are ostracised. One is the narrator, now grown, ostracised for being an out-of-towner who doesn’t wear the right clothes. The other is more ostracised still, because her parents are immigrants, because she smells like rotting fruit, and because her brother needs her to accompany him to the toilet. When this girl is dying in hospital from child leukemia, the young narrator is filled with inexplicable grief. It is now too late to be a real friend to this outcast, and anything she does in kindness will feel empty and pointless.

- “Boys and Girls” — An outdoorsy farm girl loves helping her father on the fox farm but realises she’ll very soon be required to go indoors to help her mother with domestic work. In contrast, her younger brother, far less conscientious, will be allowed to stay outside and work with the animals, enfolded and welcomed into the masculine world.

- “Postcard” — A woman around the age of 30 has been seeing a man for years. They’re long-term partners. The reason they haven’t married: He’s waiting for his mother to die. His mother wouldn’t approve of him marrying the narrator, we deduce because of the wealth disparity. Unfortunately for the narrator (Helen), turns out the guy never intended to marry her anyway. He sends her a postcard from Florida telling her how he’s having such a good time. Next minute, Helen’s best friend is round to break the bad news: It’s been published in the paper, the lover is getting married to someone else after all this time. The weasel didn’t have the gumption to let Helen know. So she goes round to his house, stands outside and expresses her grief in a very vocal way.

- “Red Dress—1946” — A thirteen-year-old girl’s first ball. Her mother sews a red dress with a princess neckline. Suddenly she looks much older. She barely recognises herself in the mirror, and longs for childhood again. Almost all the girls around her are obsessively interested in boys. Everyone, that is, except one other girl who says she despises boys, and plans to support herself by working as a P.E. teacher. But by aligning herself with this queer girl, our thirteen-year-old risks much. What will she do? Will she take up the offer of friendship?

- “Sunday Afternoon” — Seventeen-year-old Alva has recently finished high school and started working as a maid for the mega-wealthy Gannetts. Today they are hosting a party at their mansion and Alva must navigate a delicate social situation: They want her to feel part of the family, but what does that mean, exactly, when you’re actually the paid help? Alva must also navigate the men who enter the house, several of whom express sexual interest in her. This isn’t your run-of-the-mill, predictable young-woman-is-seduced storyline, but Alice Munro keeps readers in audience superior position as we watch with bated breath what happens to Alva in this big, lonely island of a house. We’re left to deduce most of it.

- “A Trip to the Coast” — An eleven-year-old girl called May lives with her mother and grandmother (mostly her grandmother) in a general store in a three-house township. There’s nothing to do in this one horse town. But today she’s looking forward to same-age company. However, the “company” is a total let-down, and so her grandmother, for the first time ever, suggests the two of them take a trip to the coast. But then another visitor comes. A customer who declares himself an amateur hypnotist. This story ends on a cliff hanger, and I don’t believe Munro has given us enough of a symbolic layer to fill in the gaps for ourselves. I believe we’re supposed to feel exactly as unmoored as eleven-year-old May, waiting out front of the store in the rain.

- “The Peace of Utrecht” — Numerous critics and scholars consider this story the jewel of the crown of Munro’s first collection. Considering that, it’s baffling why it doesn’t make it into more Selected and Collection volumes. It’s certainly the most overtly personal of Munro’s early stories, and she has said in interview that this one changed the way she wrote. Until writing “The Peace of Utrecht” she’d written to be a writer. Now she wrote because she knew only she could write this story. The biographical relevancy: young Alice Munro cared for her mother over many years as her mother lived, then died, with Parkinson’s disease.

- “Dance of the Happy Shades” — An emotionally astute and very observant adolescent girl is required to accompany her mother to an embarrassing recital with the elderly, unfortunate-looking spinster teacher whose spinster sister is recently bedridden due to a stroke. The story is told via the slightly baffled viewpoint of the girl, who is required to recite a tune on the piano at these excruciating annual events.