The culture, as as whole, despises teenage girls. Let’s take a look at the evidence in pop culture and storytelling.

When I taught in a girls’ high school, I generally had two reactions when sharing what I did for a job. The first was, ‘Oh god, I could never teach teenage girls. (Teenage girls are Too Much.)’

The second reaction, which came most often from teachers who taught in co-ed schools, was that teaching girls was a walk in the park, because girls are so much more compliant and therefore better behaved in the classroom. So which is it?

Neither of those is true, and I have since had time to consider where these ideas come from. Misogyny is the short answer.

Let’s get a bit more specific though. I’ve collected a few examples of teenage-girl-hatred from pop culture.

Here is an example of a typical adolescent girl in adult, mainstream fiction from the 1990s. Okay, this is getting a bit old now, but I’ll get to the recent stuff further down:

‘Only because I told you every time he looked uncomfortable,’ reminded Loren, who had that pretty but gangly appearance of many twelve-year-old girls, pre-teenage and just beginning to take a greater interest in what was worthy of ‘cool’, be it music, clothes, or Mother’s make-up. Sometimes she assumed a maturity that should not yet have been learned, while at other times she was still his ‘princess‘ who loved her dolls and frequent hugs (the latter more occasional than frequent these days).

Loren had been adamant that no way was she leaving her friends and school in London to live in a place thousands of miles from anywhere, a place where she didn’t know anybody, a place she’d never even heard of. It took some persuasion, plus a promise of having her very own cell phone so that she could keep in constant touch with all her girlfriends, to convince her things would be okay in Devon. […]

[Her father] realised at that moment that he missed the extra ‘d’ and the ‘y’ at the end of ‘Dad’ and wondered when it had started happening. Was Loren, his princess, growing up so fast that he hadn’t noticed? With a jab of melancholy that perhaps only fathers of growing daughters can know (sons were way different, except to doting mothers), he swung back in his seat, glancing at Eve as he did so.

The Secret of Crickley Hall, by James Herbert

I wouldn’t accuse James Herbert of being a great stylist, nor would I count him as a writer who offers insights into the complexities of human nature. But I would expect a little more imagination from any published and much promoted author, instead of relying solely on the trope.

As noted on the TV tropes page, ‘If the teenage daughter is the show’s protagonist, she probably won’t be this character, or at least, not as extreme a version.’ To paraphrase: in stories about teenage girls, for teenage girls, the main character is likely to be more rounded. The problem with this is, it is mainly teenage girls (and some adult women) are reading books about teenage girls.

I’d like to see fewer bratty-sullen-teenage-girl tropes in fiction. I’ll include an example by a woman author to show it’s not just men.

All she wanted today was the tree in the house, the old songs with their promises that the world would be remade with the birth of a baby, and to be Benny’s age, sitting with her family on Christmas morning, opening her presents and finding them all surprising and marvellous, no matter how inconsequential. She wanted everyone kind and affectionate, not passionate and tormenting–everything open, no maggoty secrets and silences, and no arguments with other, darker arguments hidden in them. Somewhere, waiting to be found again in the approaching season, was an old, innocent self, sexless as a tennis racquet, living in a time before Jack and Naomi [her parents] wept at each other late at night, and before she had made Belen a body and wings of words or allowed Prince Valery it joke at the expense of innocence. In those days she had floated on her back in the moonlit sea, watching Orion swing himself up from the water to lie over her, while the finished people, the adults, on the shore had laughed, eaten, drunk, flirted and even embraced secretly in the shadows. But that old innocent self would not come again. It was gone forever, and something else was trying to replace it.

The Tricksters by Margaret Mahy

Women internalise hatred of their own teenage selves. (And when they become mothers, pass it down to their daughters.)

The casualness in the sentence below should shock and surprise us. What if this generalisation were applied to literally any other group? (This author a.k.a. Lemony Snickett isn’t exactly renowned in writing circles for being nice, though):

Handler’s Min is smart, ever-so-slightly pretentious, and prone to fits of melancholy—just like, ya know, every actual teen girl reading the book.

Barnes & Noble review of Daniel Handler’s Why We Broke Up, because all teenage girlswho read this bookare obviously exactly the same

Here’s some teenage girl hatred in movie reviewing:

ACNE: Acronym for Adolescent Character’s Neurotic Envy Syndrome, which usually afflicts shrill teenage blonds in movies about how the good girl wins the hero away from the syndrome sufferer. (See “Secret Admirer”)

Ebert’s Guide to Practical Filmgoing: A Glossary of Terms for the Cinema of the ’80s

Dead Teenager Movie: Generic term for any movie primarily concerned with killing teenagers, without regard for logic, plot, performance, humor, etc. Often imitated; never worse than the “Friday the 13th” sequels.

Ebert’s Guide to Practical Filmgoing: A Glossary of Terms for the Cinema of the ’80s

An Australian example: Chris Lilley’s Ja’mie: Private School Girl.)

The genre of reality TV is an especially obvious example of the ways in which storytellers like to depict teenage girls and young women.

People are studying this stuff:

The report took the form of a survey, and asked tween and teen girls, both reality show watchers and non-watchers, a variety of questions about what they saw on reality TV and how it affected them. The results were rather disheartening, with a majority of girls stating that reality TV places girls in direct competition with each other (86%) and that gossip is a normal part of a friendship between girls (78% of reality show watchers compared with 56% of non-watchers). And boys certainly also come into play: more watchers than non-watchers feel that girls need to compete with each other for male attention (74% vs. 63%) and that they feel they’d be happier if they had a boyfriend (49% vs. 28%).

from The Mary Sue

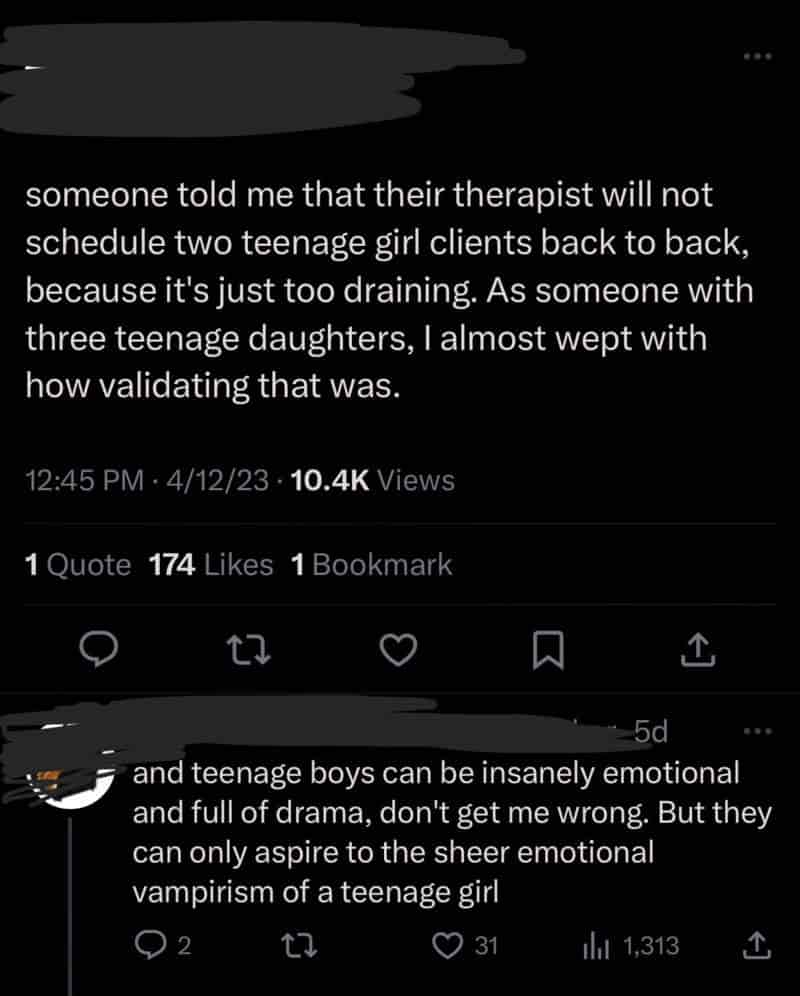

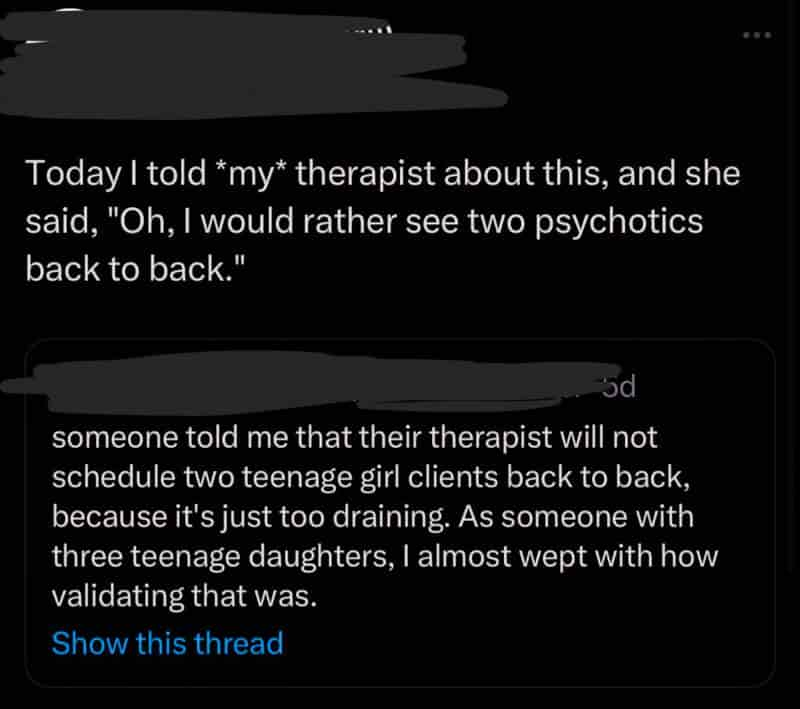

Reality TV has never been the bastion of all that is good in the world, so let’s take an example of teen-girl hatred from… therapists, via Kaitlin Ruiz. People whose actual job is to care.

The way people hate their daughters is so fvcking sad. any adult who thinks it’s ok to treat teenaged girls with disdain is telling you a lot about their own character (rotten!).

I just don’t get how anyone can grow up and look back on their adolescent girlhood–when everything is cramped and confusing and too much, when your body itself abandons stoicism–and go on about how teen girls are emotional vampires. there’s not any meaningful difference between this stuff and the creeps who fetishize young girls.

Being a teenaged girl means that you’ve been cut off from any charity childhood might’ve granted you. all your intentions, your growth spurts, your failures are now read as malicious.

Girls are up against so much. Please be good to your daughters.

I just think it’s kind of wild that “we must ensure teen boys aren’t alienated so they don’t shoot up a school” is somehow common sense alongside “teen girls are so needy and demanding”.

I was a pretty moody and withdrawn kid, and by thirteen I’d just burst into tears out of nowhere. one time, standing at the kitchen counter, I started crying without prelude. my grandpa, baffled, put his arm around me and said “poor girl,” over and over till I was done.

I think about that all the time. He didn’t know what was going on–and neither did I, really. but he was willing to care.

For those asking about the therapist involved: I don’t have any connection to them or OP, so I can’t direct you to any resources / licensing board, etc. For those responding with variations of “well, actually–,” I defer to David Lynch: fix your heart.

@Kaitlin_M_Ruiz, 7:49am · 18 Apr 2023, Twitter

GIRLS AS PUNISHMENT FOR BAD FATHERS

I think it’s a [writing] choice to give a guy like that [Mickey Rourke’s character in The Wrestler]. Especially a lesbian daughter, which I think implies, at least in his opinion maybe, that she is a lesbian because she hates men because of him? Which is kind of what I got from it. And Rachel Wood, queer actress, so that’s cool. But my sister and I, we have the same mom and then [our own father] has got two other kids from other women. And my mom would say, like a joke, when we were younger, that like, my dad having two daughters was his punishment, for how he behaved.

That’s a thing people say a lot, in a weird way!

Yup. They do.

Ugh. About like how girls are hard? What is that?

It’s because my dad was like a drunk and a skirt-chaser. He now has two girls who might have to deal with men like him. That’s the joke.

“The Wrestler” w. Gaby Dunn at the movie discussion podcast “You Are Good”.

A sympathetic view

Teenage girlhood is almost like a cult. Only the ones who have been through it understand how hellish it can be. It is a world on its own that is so vastly complex and different from the male experience, and frankly, make for more compelling stories.

Cinema has long tried to explore these secret, dark parts of teenage girlhood. Astute directors and writers have realized that it is a breeding ground for horror stories. The teenage girl sees everything and feels everything with such intensity. Everything burns. So turning these experiences into a fantastical, heightened story is only natural.

Teenage girls are also particularly misunderstood and marginalized group. The media treats her with disdain. Her interests are frivolous and unimportant. She is sexualized and fetishized for her innocence and budding sexuality. Her moodiness and angst is a way of attention seeking. Meanwhile, schools all over the world still continue to study Holden Caulfield’s dribble and see his white upper middle class angst as “complex”.

Hell is a Teenage Girl: The Teenage Girl Killer’s Place in Horror Cinema by Natalie Ng

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

REAL GIRLS, FAKE GIRLS, EVERYBODY HATES GIRLS from The Zoe Trope talks about Mary Sues and coins a word for her counterpart: the Sarah Jane. “It turns out the vast majority of talk about Sarah-Janes – realistic, flawed, prominent female characters in fiction – *still* centres on what is wrong with them, and all the reasons they are SO ANNOYING for… not being perfect?”

HOW NOT TO TALK ABOUT ADDING A FEMALE CHARACTER TO YOUR STORY, TOLD BY RAGEFACES from The Mary Sue

We care about young women as symbols, not as people from Laurie Penny at NS (paywalled)

NEW STUDY SAYS TEENAGE GIRLS ARE SEXUALIZED ON NETWORK TELEVISION from The Mary Sue

Regarding the tendency for girl stars to pose naked for men’s magazines once they hit adulthood:

It’s not just attempts to classify these spreads as empowerment that’s so frustrating. It’s the photos’ implicit suggestion that little girls growing up is somehow remarkable, or dirty, or wild. Why do we continuously liken the release of these photos to “good” girls gone “bad”? Why do we still put such a premium on feminine purity that any evidence to the contrary becomes news?

from Policy Mic

Quoting from a GQ article, Group Think points out the sexism of certain kinds of journalism (i.e. sh*tty journalism):

“By now we all know the immense transformative power of a boy band to turn a butter-wouldn’t-melt teenage girl into a rabid, knicker-wetting banshee who will tear off her own ears in hysterical fervour when presented with the objects of her fascinations. Hasn’t this spectacle of the natural world – like the aurora borealis or the migration of wild bison across America’s Great Plains – been acknowledged?”

GC

The GQ writer who published that is either oblivious to or doesn’t care about the historic (though uncomfortably recent) use of the word ‘hysteria’ to describe and disempower women.

Female Heroes in Young Adult Fantasy Fiction: Reframing Myths of Adolescent Girlhood

The heroic romance is one of the West’s most enduring narratives, found everywhere, from religion and myth to blockbuster films and young adult literature. Within this story, adolescent girls are not, and cannot be, the heroes. They are, at best, the hero’s bride, a prize he wins for slaying monsters. Crucially, although the girl’s exclusion from heroic selfhood affects all girls, it does not do so equally- whiteness and able-bodiedness are taken as markers of heightened, fantasy femininity.

Female Heroes in Young Adult Fantasy Fiction: Reframing Myths of Adolescent Girlhood (Bloomsbury, 2023) by Dr. Leah Phillips explores how the young female-heroes of mythopoeic YA, a Tolkienian-inspired genre drawing on myth’s world-creating power and YA’s liminal potential, disrupt the conventional heroic narrative. These heroes, such as Tamora Pierce’s Alanna the Lioness, Daine the Wildmage, and Marissa Meyer’s Cinder and Iko, offer a model of being-hero, an embodied way of living and being in this world that disrupts the typical hero’s violent hierarchy, isolating individuality, and erasure of difference. In doing so, they push the boundaries of what it means to be a hero, a girl, and even human.

New Books Network

Teenage Dreams: Girlhood Sexualities in the U.S. Culture Wars

Utilizing a breadth of archival sources from activists, artists, and policymakers, Charlie Jeffries’ Teenage Dreams: Girlhood Sexualities in the U.S. Culture Wars (Rutgers UP, 2022) examines the race- and class-inflected battles over adolescent women’s sexual and reproductive lives in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century United States. Charlie Jeffries finds that most adults in this period hesitated to advocate for adolescent sexual and reproductive rights, revealing a new culture war altogether–one between adults of various political stripes in the cultural mainstream who prioritized the desire to delay girlhood sexual experience at all costs, and adults who remained culturally underground in their support for teenagers’ access to frank sexual information, and who would dare to advocate for this in public. The book tells the story of how the latter group of adults fought alongside teenagers themselves, who constituted a large and increasingly visible part of this activism. The history of the debates over teenage sexual behavior reveals unexpected alliances in American political battles, and sheds new light on the resurgence of the right in the US in recent years.

New Books Network