The Tale of Mr. Tod by Beatrix Potter (1912) is a child-in-jeopardy crime thriller. See my post on thrillers and also my post on secrets and scams.

Note alo, crime stories appeal disproportionately to women — for whatever reason, this is a female genre. Beatrix Potter was the perfect candidate to create such a work.

Also, if you want to see what sort of sociopathic, philosophising white man Peter Rabbit turned into, go no further than Mr. Tod — the unexpectedly dark sequel to The Tale of Peter Rabbit. Potter wrote this mindfully and opens with direct address:

I have made many books about well-behaved people. Now, for a change, I am going to make a story about two disagreeable people, called Tommy Brock and Mr. Tod.

Actually, Potter did not use the word ‘nice’. What she wrote was this:

I am quite tired of masking goody goody books about nice people.

The publishers made her change it.

I wonder if, by 1912, Potter had become weary of people’s assessment of her work. Even today, I feel Beatrix Potter is mischaracterised as a spinster who wrote cosy tales about bunnies dressed in coats. But you’d only believe that if you hadn’t actually read any of her stories. More recent made-for-TV bowdlerisations don’t help. Is the opening to Mr. Tod a note to the people who underestimate her darkness?

Nobody could call Mr. Tod “nice.” The rabbits could not bear him; they could smell him half a mile off. He was of a wandering habit and he had foxey whiskers; they never knew where he would be next.

If Potter were alive today, I can guess what she’d say to people who insist people — women in particular — write likeable characters as role models for children. I think she’d tell them where to stick their opinions.

LANGUAGE IN MR. TOD

coppice — an area of woodland in which the trees or shrubs are periodically cut back to ground level to stimulate growth and provide firewood or timber. This suggests humans are living nearby, though the animals in Beatrix Potter stories are referred to as ‘people’, so it could’ve been maintained by the animals themselves.

to cut a caper — to make a playful skipping movement (it does not mean to slice a pickle, of the sort I’ve only ever encountered at Subway sandwich restaurants)

spud — I thought it referred to potatoes, but now I realise it’s a small spade, and potatoes probably came to be called spuds after the spade used to dig them up. (Looks like no one really knows if that’s the connection — before it was a little spade it was a Nordic dagger. I imagine these were used to cut tubers up. Vikings didn’t have potatoes, however. I’m stumped!)

pig nuts — One of the more palatable wild foods. The tuber can be eaten raw and is very tasty. In flavour and consistency pignuts are something like celery heart crossed with raw hazelnut or sweet chestnut and sometimes have a spicy aftertaste of the sort you get from radishes or watercress.

flags — in this contest it means flagstone, used as flooring.

coal scuttle — a bucket-like container for holding a small, intermediate supply of coal convenient to an indoor coal-fired stove or heater.

counterpane — an old-fashioned word for a bedspread

bedstead — the framework of a bed on which the mattress and bedclothes are placed

warming-pan — A bed warmer was a common household item in countries with cold winters, especially in Europe. It consisted of a metal container, usually fitted with a handle and shaped somewhat like a modern frying pan, with a solid or finely perforated lid.

monkey soap — Monkey Brand soap was introduced in the 1880s in cake/bar form in the United States and United Kingdom as a household scouring and polishing soap. (Today the publishers would be required to capitalise the M to avoid getting sued for promoting brand generification)

persian powder — Persian powder is a green pesticide that has been used for centuries for the biological pest extermination of household insects.

kitchen fender — Here’s a picture of one. It’s made of steel but what is it for? Looks like a guard for the stovetop.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

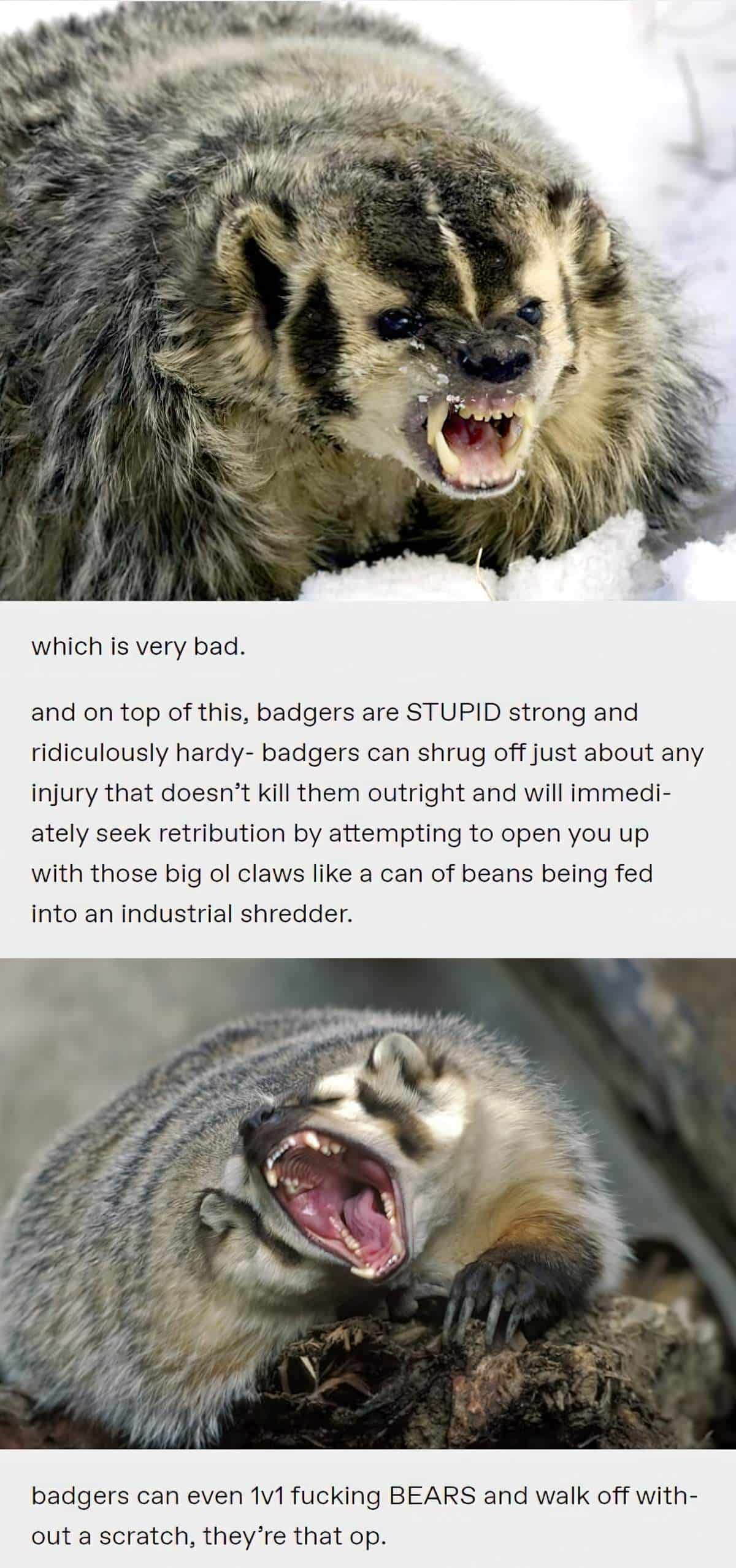

- Tommy Brock — a vile badger who sleeps all day and is therefore considered lazy (the curse of shift workers everywhere)

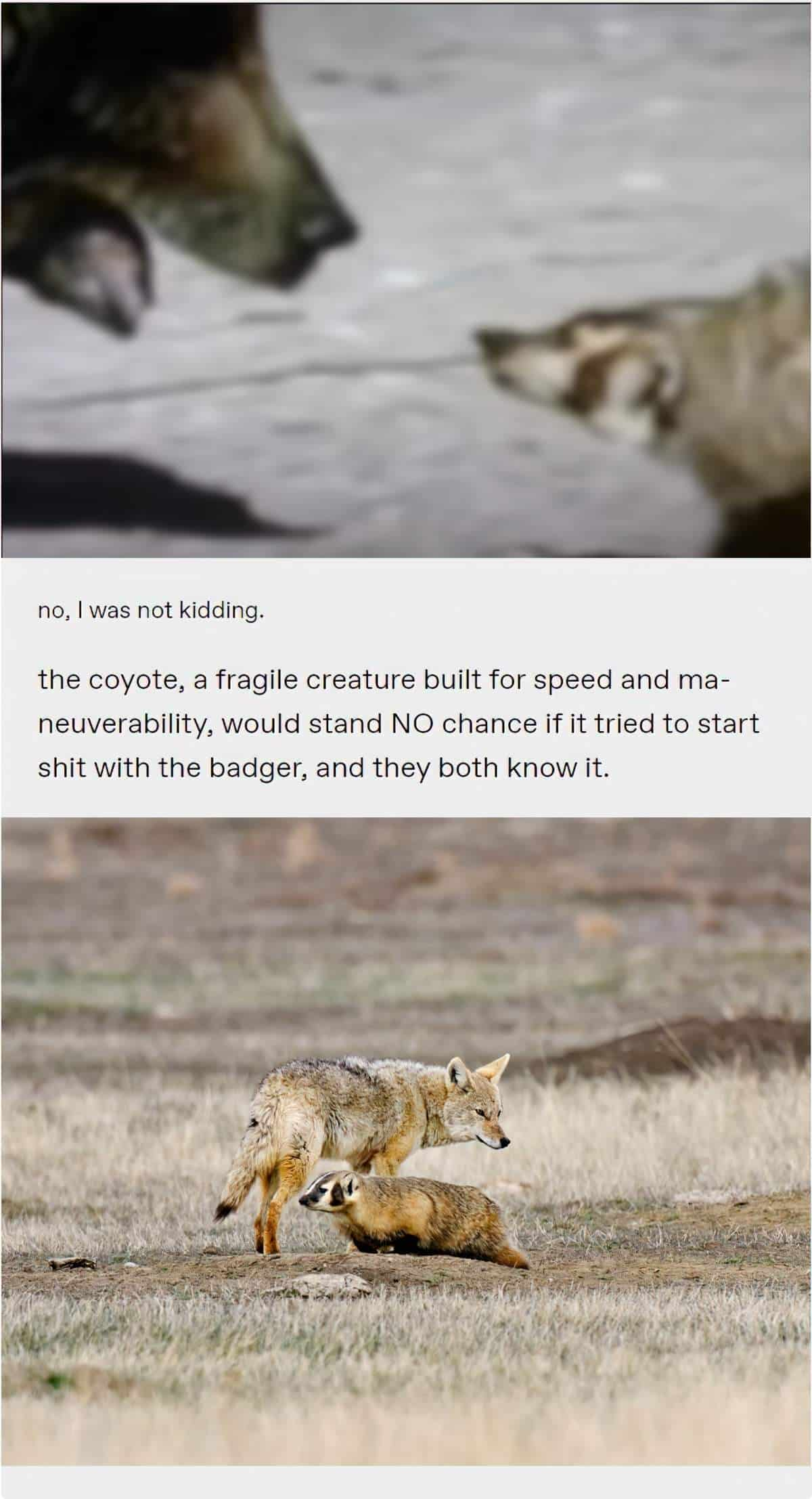

- Mr. Tod — a fox who likes to eat rabbits, rats etc. Sly.

- Mr. Benjamin Bouncer — terrorised by Mr. Tod, old, too old for proper babysitting but there we have it. Because he is old he is the designated dolt — easily tricked by a badger carrying a bag full of his grandbabies. I mean, Brock even stops to have a chat with him.

- Benjamin Bunny — Benjamin Bouncer’s son

- Flopsy — married to Benjamin. She cleans when she’s had a gutsful.

- The bunnies — they spend the entire story in a sack, pretty much. They’re more goods than characters.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE TALE OF MR TOD

Potter intends two main characters: Tommy Brock and Mr Tod. These guys are nemeses. The rabbits end up functioning as viewpoint characters as well as victims (mostly viewpoint characters). But they have their parallel plot, more reminiscent of a sprawling contemporary crime TV series than of a picture book.

Fairytale elements, such as from Hansel and Gretel are utilised in this story, as well as the classic character archetypes typical of Aesop (especially the sly fox). Then there’s the Goldilocks reference, with someone breaking in to some fierce creature’s house and accidentally falling asleep in their bed. But the forest and the trickery would be at home in almost any European fairytale.

SHORTCOMING

Mr Tod’s shortcoming is also his strength, as explained above:

Nobody could call Mr. Tod “nice.” The rabbits could not bear him; they could smell him half a mile off. He was of a wandering habit and he had foxey whiskers; they never knew where he would be next.

(He has ‘foxey’ whiskers because he is an actual fox, which is an interesting way of telling us that.)

I love the thumbnail character description of Tommy Brock:

Tommy Brock was a short bristly fat waddling person with a grin; he grinned all over his face. He was not nice in his habits. He ate wasp nests and frogs and worms; and he waddled about by moonlight, digging things up.

Only from the illustrations do we know for sure that Tommy Brock is a badger, though brock is a British name for a badger, so if you know that you didn’t need the illustration.

DESIRE

Does the badger really mean to kidnap those tasty little bunnies? I don’t think he meant to until he saw the opportunity. Remember he’s high on something potent — whatever ‘cabbage leaf’ cigar stands for. Ditto ‘seed cake’. I mean, he goes to the fox’s house, probably thinking it’s his own home. He sleeps and doesn’t move even when a fox comes into his house, probably thinking it an hallucination. He doesn’t give a shit, does he. He’s put the bunnies in the oven but forgot to turn it on. He’s off his face.

That fox isn’t off his face though. He comes home after a bad night of hunting and he’s wanting some breakfast. When he finds the badger in his bed, he only means to wake him up with a cold water surprise.

OPPONENT

Potter was familiar with the dietary requirements of a badger:

They can eat several hundred worms each night. But being omnivorous, they will eat almost anything, from flesh and fruit to bulbs and bird eggs. … They will eat nuts, seeds and acorns along with crops like wheat and sweetcorn. Badgers are known to eat small mammals mice, rats, rabbits, frogs, toads and hedgehogs.

Woodland Trust

When Potter’s narrator tells us that badgers only occasionally eat rabbit pie and only when there’s nothing else around she is setting up a hierarchy of opposition, with the fox as the most dangerous of all.

But even the rabbits have their own conflict. It strikes me what an absolute asshat Peter Rabbit has turned into — the returned and bereft Benjamin Bunny is worried sick — as you would be — that his babies are about to be consumed, the entire lot of them. But what does Peter do? Constant deflection and circumlocution. He’s in no hurry whatsoever. In fact, Peter Rabbit almost gives one the impression that he’d like the bunnies to be eaten. That experience in Mr. McGregor’s garden ruined him for empathy.

Look at how deliberately unhurried he is. Who cares how many? Who cares how hard caterpillars kick? I mean, under the circumstances!

“Whatever is the matter, Cousin Benjamin? Is it a cat? or John Stoat Ferret?”

“No, no, no! He’s bagged my family—Tommy Brock—in a sack—have you seen him?”

“Tommy Brock? how many, Cousin Benjamin?”

“Seven, Cousin Peter, and all of them twins! Did he come this way? Please tell me quick!”

“Yes, yes; not ten minutes since … he said they were caterpillars; I did think they were kicking rather hard, for caterpillars.“

“Which way? which way has he gone, Cousin Peter?”

“He had a sack with something ‘live in it; I watched him set a mole trap. Let me use my mind, Cousin Benjamin; tell me from the beginning.” Benjamin did so.

“My Uncle Bouncer has displayed a lamentable want of discretion for his years;” said Peter reflectively, “but there are two hopeful circumstances. Your family is alive and kicking; and Tommy Brock has had refreshment. He will probably go to sleep, and keep them for breakfast.”

PLAN

Ben’s plan is to chase the dude with the sack full of bunnies. This is a classic thriller chase, with near misses, hazards on the way (Mr. Tod’s house), snags (the sack has gotten caught on twigs, leaving bits of thread).

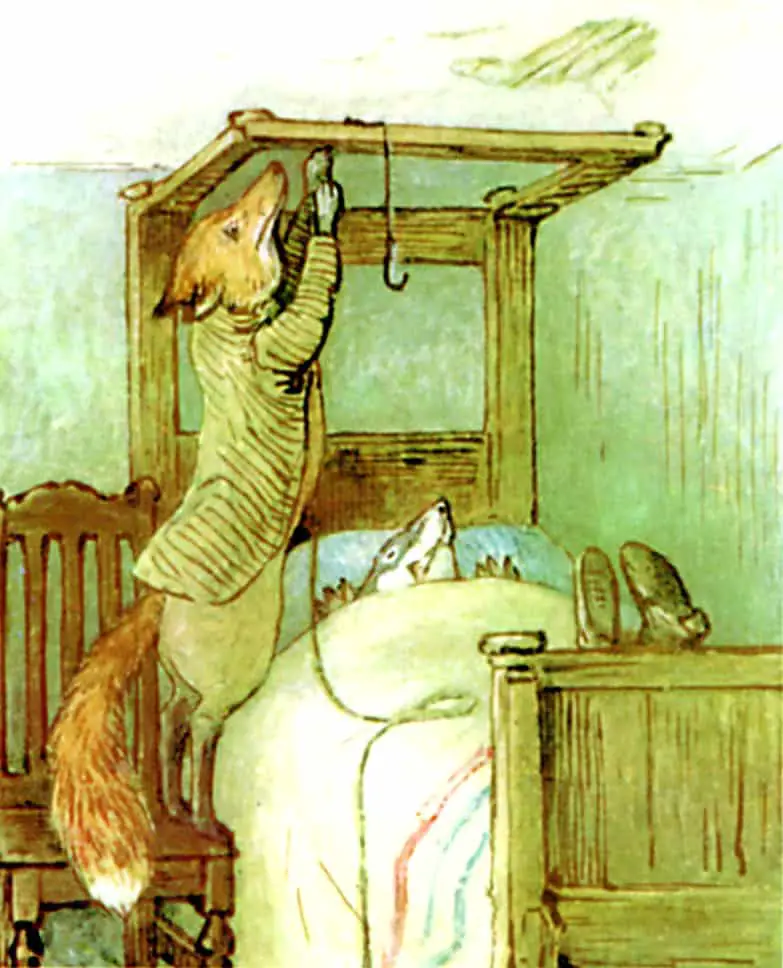

The second half of this story mainly comprises the elaborate scheme the fox gets up to — a prank, basically, designed to rouse the badger, who has accidentally fallen asleep in his bed. The fox is scared of the badger’s teeth, so doesn’t want to do anything violent at close range.

The badger is onto him and replaces himself with the fox’s rolled up dressing gown, safely escaping a wet fate. But he’s not going to get out before enjoying the look on fox’s face when his prank fails.

(The badger is a proxy for the baby rabbits. The baby rabbits never genuinely come near death. It was always the badger who was for the chopping block.)

Peter and Benjamin have spent the night digging a tunnel under the house, hoping to rescue Ben’s children that way. This plan is interrupted when the fox returns home after a night hunting.

Notice how Potter depicts Benjamin and Peter on both sides of the window — once from their point of view, once from the point of view of the bunnies in the oven.

See also: The Symbolism of Windows

BIG STRUGGLE

The thriller aspect of this story begins as the pacing dilates.

When they came near the wood at the top of Bull Banks, they went cautiously. The trees grew amongst heaped up rocks; and there, beneath a crag—Mr. Tod had made one of his homes. It was at the top of a steep bank; the rocks and bushes overhung it. The rabbits crept up carefully, listening and peeping.

This change in pace, the emphasis on detail at the life-and-death moment, that is typical of a thriller.

The fox’s house itself is the set of a horror or a thriller:

This house was something between a cave, a prison, and a tumbledown pig-stye. There was a strong door, which was shut and locked.

The setting sun made the window panes glow like red flame; but the kitchen fire was not alight. It was neatly laid with dry sticks, as the rabbits could see, when they peeped through the window.

But this is still a children’s book, after all. Potter does lighten the tone in several ways.

First, it happens Peter Rabbit is right. (I don’t think this absolves him of his sociopathy) and the young reader will sympathise with Peter Rabbit from having read Potter’s initial story starring him. So we are meant to believe him when he says don’t worry, the bunnies will be fine, just fine.

Second, the comical snoring. The description of Mr. Tod’s snoring seems designed to provide comic relief, though I’m not sure it works much.

If I didn’t know this video had been dubbed over with a woman’s snoring I would’ve assumed the snoring was a part of the original foley.

The Battle scene includes a tantrum, as children’s stories often do — the fox seems to want to control his temper. He takes a moment to go outside and have a bit of a meltdown. He decides a coal-scuttle and walking stick won’t do for weapons. The badger has quite fearsome teeth. (This reminds me of Little Red Riding Hood.)

Peter and Benjamin come near death when the fox trips over their shallow burrow.

While the fox and badger are having an actual fight, the bunnies escape.

ANAGNORISIS

The plot revelation: The bunnies are safe inside the oven.

There’s a bit of a moral to this story which comes out in the rabbit’s house — we should forgive people who do great wrong, especially if things turn out all right.

NEW SITUATION

At home in the rabbit-hole…

Now everything is cosy again. Well, sort of. Things will never be the same now that Mr. Bouncer has proven himself a totally irresponsible grandfather, letting in a monster, getting high together, basically handing over his own grandbabies.

But when the men arrive home with the rescued babies, Flopsy forgives her father-in-law and he is rewarded with a pipe, even though the misdemeanour of negligence hasn’t changed. (I wouldn’t hire him again, would you?)

The plot ends with a story around the fire before bedtime, turning this into a circular, repeating structure.