“Taking The Veil” is a short story by Katherine Mansfield, published in her collection The Dove’s Nest (1930). Our main character Edna should be feeling great right now. She’s eighteen, she’s beautiful and she’s in love. One slight problem. She is about to become a Bride of Christ, also known as taking the veil. (Or so we think from the title!)

Mansfield was expert at varying emotional valence from scene to scene on the page, and “Taking The Veil” is an excellent example. Check out “The Swing of the Pendulum“, “The Singing Lesson“ and “Bliss” for others.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “TAKING THE VEIL”

What outwardly happens: A young woman called Edna walks from the library to the cathedral holding a black book. She sits in the garden and overhears the choir practising. The main story takes place inside her head. The outward story is underwhelming so, in order to work, the story inside her head is melodramatic. In this parallel ‘head story’, Edna even dies from an illness after rescuing a small animal.

Whether Edna’s fantasy happens in the veridical world of the story, or whether it happens only inside Edna’s mind, for storytelling purposes it doesn’t matter.

That is a useful takeaway point for writers when crafting highly imaginative characters like Edna, who looks to the rest of the world like a staid young conservative Catholic girl on the brink of marriage, but who on the inside is absolutely roiling.

ESCAPE INTO IMAGINATION

Perhaps “Taking The Veil” came about because the unconventional ‘remittance woman’ Katherine Mansfield, the writer, wondered if even her staid, gender-conforming counterparts also experienced ‘break-free’ fantasies. For a conventional girl, what might a break-free fantasy have looked like? We have an example in Edna. Ironically, comically, Edna’s idea of breaking free is to join a nunnery.

The story structure is similar to a carnivalesque children’s story such as Cat In The Hat or The Tiger Who Came To Tea. A character goes about their regular mundane life but an imagination (or imaginative) character appears out of nowhere. Our main character has fun living a completely different life.

The story ends with a return to safety and to the mundane realities of the real world. (It’s basically a home-away-home structure.) In picture books for toddlers, the aim of these stories is simply to have fun. But in a lyrical short story such as this one, the main character escapes her mundane life via a fantasy, and by doing so she does learn something. In this case, Edna will remind herself of her love for her fiancé. I argue below that this is not an epiphany, per se. Edna is not a self-aware character, and experiences no true anagnorisis. But the melodrama does become increasingly melodramatic until she feels quite downcast, at which point she snaps out of her diverting fantasy.

MANSFIELD AND CATHOLICISM

Unlike her fictional creation of Edna, Katherine Mansfield herself was not a product of a Catholic educational system. She attended Wellington Girls’ High School, a New Zealand public school. But Mansfield was no doubt surrounded by Catholicism later, especially when she lived in France.

The French literary movement at the beginning of the 20th century was hugely influenced by Catholicism. This return to Catholic ideas was a reaction against the Positivism, Naturalism and materialism of the 19th century. Ironically, many right-wing, Catholic, French literary critics were reacting against Modernism at the time but loved the stories of Katherine Mansfield. This is ironic because Mansfield was later regarded as an author working at the vanguard of Modernism (which they said they despised). For more on that see Katherine Mansfield: The view from France by Gerri Kimber.

Katherine Mansfield was in essence a queer leftie. If she’d lived in our time she’d have had her septum pierced and would be sporting sleeve tattoos of carnations and birds. “Taking The Veil” isn’t a story about the Catholic tradition of becoming a nun. Nor does it make use of Catholic symbolism (unlike, say, horror from the West which is full of it). Mansfield wasn’t able to view Catholicism from the inside, and neither can I.

SETTING OF “TAKING THE VEIL”

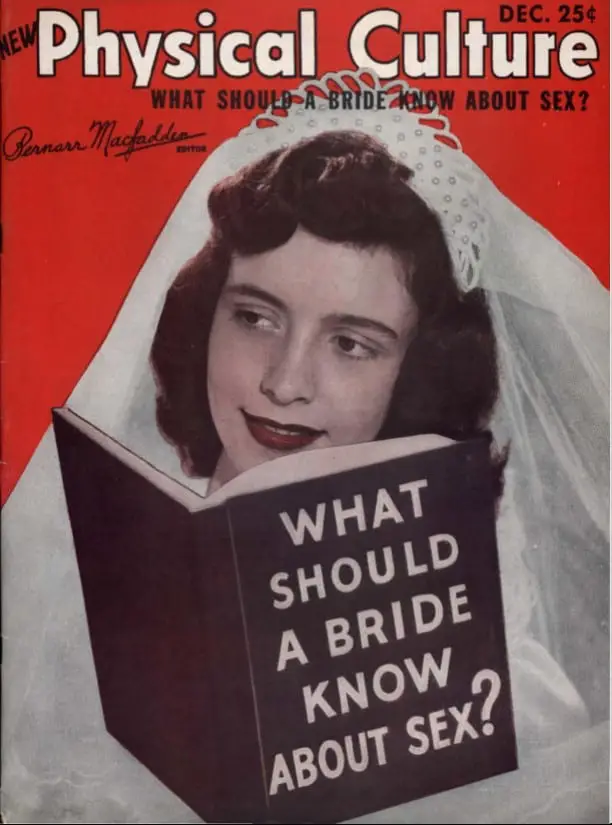

Instead, Mansfield is exploring the tumultuous feelings of being young and in love, falling in lust in an instant, but also being afraid of matrimony and sex. Mansfield juxtaposes temporary sparks of lust against the long-term, safe kind of love, and explores how a young Catholic woman might tame these emotions into something acceptable, something safe to show to the world. In order to explore these ideas in fiction, the context of a restrictive Catholic tradition comes in handy.

The story opens on a beautiful, utopian day.

IT seemed impossible that anyone should be unhappy on such a beautiful morning. Nobody was, decided Edna, except herself. The windows were flung wide in the houses. From within there came the sound of pianos, little hands chased after each other and ran away from each other, practising scales. The trees fluttered in the sunny gardens, all bright with spring flowers. Street boys whistled, a little dog barked; people passed by, walking so lightly, so swiftly, they looked as though they wanted to break into a run. Now she actually saw in the distance a parasol, peach-coloured, the first parasol of the year.

“Taking The Veil”

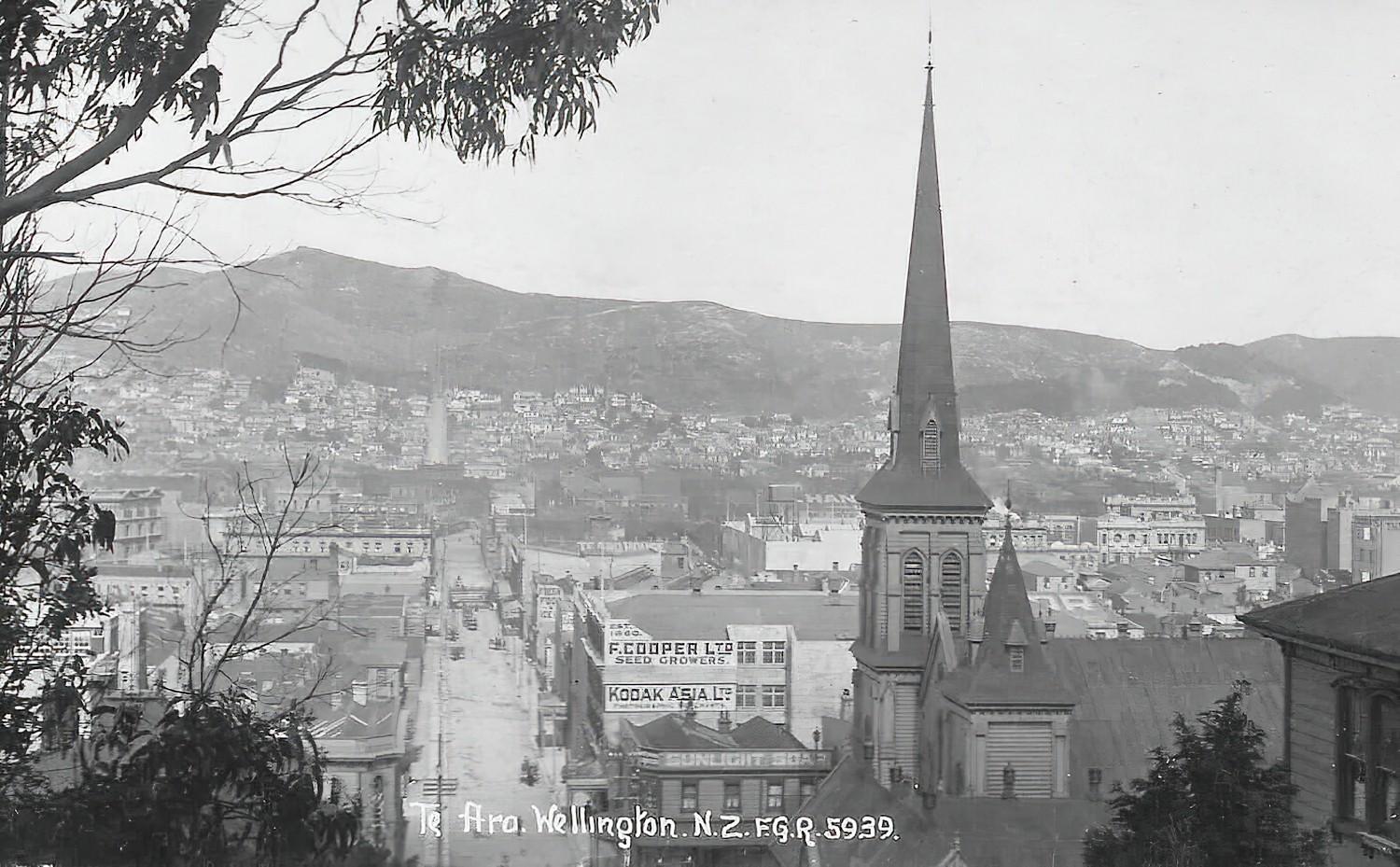

This postcard shows us a Wellington Mansfield never quite knew. Apparently the photo was taken around 1925. It’s the suburb of Te Aro with (possibly?) St John’s Church on Dixon Street, looking towards Courtney Place, and Mt Victoria in the distance.

Katherine never returned to New Zealand after sailing away for the second time on July 6, 1908, but this mid 1920s picture of Wellington is closer to Mansfield’s memory of Wellington than to the built-up New Zealand capital of today. (I do wonder which church Mansfield was imagining when she wrote this story.)

How does Edna really feel?

Edna’s positive view of her environs even as she (ostensibly) feels like crap must be a close cousin to pathetic fallacy, in which a character’s environs afford insight into their internal state. Is Edna really all that miserable? I don’t reckon. Here’s the clue:

Perhaps Edna did not look quite as unhappy as she felt.

Inversely, perhaps Edna did not feel quite as unhappy as she looked. At any rate, Mansfield is telegraphing that this character is not as she appears. I put it to you that Edna’s world looks great because Edna feels great. (Later in the story it becomes clear that Edna takes a Gothy delight in her own melancholy.)

Today Edna is playing a role. She’s trying ‘nun’ on for size, probably inspired by the book she’s got out of the library. And how are nuns supposed to act? The archetypal nun emanates a staid, steady, calming presence. This may give an overall impression of sadness. Our cultural notion of nuns is key here. Despite a century between Mansfield and the contemporary reader, my expectations of ‘proper nun comportment’ are no doubt shared by Edna. We all make use of pop cultural stereotypes and scripts. When Edna tries ‘nun’ on for size, she is also trying on ‘sadness’.

At the story’s opening, I suspect any negative feelings derive from Edna’s nervousness at the prospect of married life. Perhaps this is a story about the Fear of Engulfment.

Fear of Engulfment is the specific female fear of being impregnated and then having to give birth, over and over and over, perhaps until the day you die. It’s easy for many people with wombs to forget the extent of this ancient fear now, but until recently this state of being was reality for any sexually active heterosexual cis women. Fairy tales such as “The Frog Princess” are said to be about the Fear of Engulfment.

Of Katherine Mansfield’s short stories, “Psychology” is a good example of a character’s fear of engulfment. The main character in “Psychology” has her own way of enjoying a sex life without penetrative, partnered-with-a-man sex. Edna’s way is similar — she enjoys the platonic company of a safe man (in this case her fiancé) while enjoying a fuller sex life in her head.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “TAKING THE VEIL”

SHORTCOMING

Edna is at an age where she’s inclined to fall in lust easily, and now she has to do something with those massive feelings.

To an outsider, Edna doesn’t have many problems. She’s in the prime of her life. She has plenty of body confidence. She knows she’s beautiful. She’s engaged to be married to her childhood best friend. She’s clearly upper middle class. We know this from mention of a nurse (ie. nanny).

Edna’s Imaginary Audience

At first the following paragraph reads like a wise statement offered via an unseen narrator, but after the description of her book, when we are firmly inside Edna’s head, we realise this entire passage describes how Edna perceives her own self:

Perhaps even Edna did not look quite as unhappy as she felt. It is not easy to look tragic at eighteen, when you are extremely pretty, with the cheeks and lips and shining eyes of perfect health. Above all, when you are wearing a French blue frock and your new spring hat trimmed with cornflowers. True, she carried under her arm a book bound in horrid black leather. Perhaps the book provided a gloomy note, but only by accident; it was the ordinary Library binding. For Edna had made going to the Library an excuse for getting out of the house to think, to realise what had happened, to decide somehow what was to be done now.

This paragraph shows that, in common with other young adult characters across Mansfield’s short stories, Edna views herself through the lens of an Imaginary Audience, constantly perceiving herself as if from another’s point of view. This is common in the years between adolescence and young adulthood, when we’re checking ourselves in shop windows, entering crowded rooms with excruciating levels of self-consciousness, wondering how we are perceived, wondering if we’re acceptable.

Some commentators pinpoint this as a feature of narcissism, but narcissism is quite different. Imaginary audience ‘syndrome’ (not a syndrome) is more to do with navigating the world in a newly adult body, and the lack of confidence that naturally attends lack of life experience. Until we’ve worked out who we are, we’re more inclined to reflect off others, using other people as our mirrors.

The problem with perceiving yourself from another’s point of view: When it becomes habit, you become disconnected from your body. Peggy Orenstein wrote extensively about this in her book Girls & Sex. (Here’s no coincidence: Peggy Orenstein wrote her BA dissertation on Katherine Mansfield in 1983.) Girls and women are highly sexualised, valued for appearance over all else. When this becomes internalised, women across a culture can lose touch with what they really want, and who they really desire.

So I consider Edna’s imagined audience and disassociated view of herself highly problematic for Edna.

DESIRE

Because she is so dissociated, Edna doesn’t know what she wants, who she wants or what constitutes enduring feelings. (This does change at the end.) It’s up to us to understand Edna’s stage in life and what she wants. How is this achieved? Via narration. If we don’t interpret the irony (Mansfield’s main ironic delivery method) we’re not going to understand Edna.

NARRATIVE IRONY

If we take a look at Mansfield’s other work, we know she was an expert with narrative irony: a writing technique in which a character presents the reader with a ‘fact’ or statement that isn’t true within the world of the story. Key point: there’s no narrator winking at the reader signalling that we are not to take the judgement at face value. Questioning everything is the responsibility of the reader. This is in line with the literary Impressionist view that there is no such thing as the real truth anyhow.

Everything we know about Edna is a deduction based on very little by way of backstory. Mansfield preferred to simply present readers with a situation almost as if the characters have been birthed for the purposes of the story at hand. In other words, her characters are presented in statu nascendi. In “Taking The Veil”, where backstory occurs, it only takes us back in time as far as the play, in which Edna falls in lust with the actor. We get a few snippets of conversation from the time Edna tried to break up with Jimmy but we don’t know when that happened. The dialogue remains suspended in space-time.

At the story’s opening, Mansfield has decided to trick readers into ‘knowing’ this about Edna:

- Edna is about to become a nun. (A deliberately tricky title!)

- Edna is in love with a flesh and blood boy.

- Edna has very recently fallen ‘in love with’ a stage actor.

EDNA’S SEXUAL ORIENTATION

When analysing characters in a text, commentators are inclined to assume everyone is allosexual. We are also inclined to assume that if we love someone romantically then we must, at some point, want to have sex with that person.

Here’s where my reading of Edna becomes very modern, and although Mansfield was ahead of her time, she didn’t have access to our modern terminology. I wonder if Mansfield has created Edna somewhere on the asexual spectrum, specifically at the aegosexual part of it. (More on this word and others similar.)

For further info on this orientation, Radio New Zealand’s Bang! podcast features an interview with someone in her thirties who identifies as aegosexual.

For me it’s a lack of interest in anything physical, but the fantasy or conceptual element is there.

Rosie, interviewed on RNZ’s Bang! podcast

Alternatively, Edna may simply be a product of her ultra-conservative times, yet to experience her ‘sexual awakening’. I suspect this is the dominant interpretation ie. Once Edna gets married and learns to share sex with her husband, she’s going to be just fine.

Some young people take longer to develop any feelings for anyone. Taking another story from that era, Anne of Green Gables, Anne Shirley is pretty similar to Edna in her thoughts about boys:

Anne often states she is not comfortable with a romantic liaison. The adolescent girl tells Marilla: “Young men are all very well in their place, but it doesn’t do to drag them into everything, does it? Diana and I are seriously thinking of promising each other that we will never marry but be nice old maids and live together forever”.

LaTrobe

(Bear in mind that Anne of Green Gables in the novel is different from how she is portrayed in a later screen adaptation. In the Sullivan Entertainment miniseries she is very aware of Gilbert’s interest in her. In fact this less likeable Anne seems to take delight at turning him down. This turns the story from a coming-of-age drama into a romantic comedy.)

Attraction can change over the course of a lifetime. (But doesn’t always.) It pays to read Katherine Mansfield through a queer lens.

OPPONENT

Any love story requires a romantic opponent. At first glance that’d be the boy Edna has known her whole life. Edna’s in love with Jimmy, but in a comfortable, queerplatonic way. Even his ‘smooth-feeling handkerchief’ is comforting. This isn’t going to provide much drama for the purposes of a short story, though we do get a glimpse into the time Edna tried to break up with him. This story isn’t about Edna’s conflict with Jimmy. This is about Edna’s psychology which led to the temporary break up with Jimmy. The human oppositional aspect is very much backgrounded.

So what of the psychology? Why is Edna wrestling with herself? Supporting my own theory of aegosexuality, if Edna were a straight allo girl wouldn’t she just marry Jimmy? The conflict and drama of this story is all inside Edna’s head. Clearly, societal expectations don’t line up with how Edna feels on the inside.

As object of her romantic fantasies, Edna fixes (for now) upon the unavailable, purely hypothetical actor she saw at the theatre the other night. We learn via Edna’s free indirect speech that she’d drop Jimmy in a heartbeat if the actor were to show any interest in her. But again, we are not supposed to trust Edna’s narrative about herself. She describes a fleeting feeling rather than a real possibility. The actor is unavailable because he and Edna are separated by a stage. Moreover, he plays a blind man, implying another barrier between them forever. Edna regards him as his an entirely fictional character, not as a flesh and blood actor. If “Taking The Veil” were a modern story, Edna might have seen him on TV and fallen equally in lust.

Later in the story we learn we were right to suspect a disconnect between Edna’s fantasies and Edna’s real world spectrum of possible actions:

The man she was in love with, the famous actor—Edna had far too much common-sense not to realise that would never be.

Chocolate has a long association with lust, which explains why Mansfield (melo-)dramatised the very small act of Edna taking a chocolate almond from a box. In storytelling and in pop narrative (especially around pop cultural ideas about premenstrual pain) chocolate is often considered a sex substitute, as well as an aphrodisiac. This makes me wonder how long chocolate has been thought of in this way. How did Katherine Mansfield think of chocolate?

Primarily symbolic of love, chocolate is a sensual food with aphrodisiac properties that are due, in part, to association. However, its melting point is the same temperature as blood.

Element Encyclopedia of Secret Signs and Symbols

PLAN

What might you do if you were a beautiful, Catholic, 18-year-old woman who loves being in love but doesn’t ever want to have sex?

Joining the convent looks like a pretty good option, right? Even more so in an era when getting married was one of the very few routes to financial security for women, who were universally expected to get married and have babies. Becoming a nun and living in genteel poverty was one of the few socially sanctioned non-marriage options for Catholic girls.

BIG STRUGGLE

The whole entire narrative is an inner battle but what’s the climax of it?

The moment Edna decided to join a convent seems impetuous on her part, coming about purely because Edna happened to be sitting in the garden of a cathedral. In stories, anagnorises must follow big struggles (yeah, it’s a rule) and Katherine Mansfield uses a few snippets from the break-up conversation she and Jimmy must have had at some point:

” But, Edna! ” cried Jimmy. ” Can you never change ? Can I never hope again? ‘:

Oh, what sorrow to have to say it, but it must be said. ” No, Jimmy, I will never change.”

ANAGNORISIS

Comically, Mansfield uses the background choir practice as a leitmotif. Their ‘ah-no’ is purely tonal, without semantic meaning, but to Edna listening from out in the garden their ‘ah no’ sounds like a cry for help. Notice too how the ‘little flower’ falls. Mansfield really liked her flower motifs:

Edna bowed her head ; and a little flower fell on her lap, and the voice of Sister Agnes cried suddenly Ah-no, and the echo came, Ah-no…

At that moment the future was revealed. Edna saw it all. She was astonished ; it took her breath away at first. But, after all, what could be more natural? She would go into a convent…

Why wouldn’t Jimmy believe his fiancée when she says she’s breaking up with him? Because it is pretty unbelievable for the era, is why. Jimmy is Edna’s best chance at a conventional life. And she does love him. In those times, in that part of the world, a girl like Edna would need some good reason to break up with Jimmy. But she is not sufficiently self-aware to understand what that reason might be. (Jimmy has no hope.) So she will settle for an ‘excuse’ rather than a reason. Hence, the convent.

Has Edna experienced a genuine anagnorisis? I don’t think so. The literary Impressionists didn’t really think that people changed just like that. Self-awareness is a slow, piecemeal affair and we get ourselves wrong.

But the reader does experience a plot reveal at this point. (Speaking for myself, anyhow.) It is now revealed that Edna’s decision to join a convent is as impetuous (and temporary) as her lust for the actor, symbolised also by the flower which fell (a universal symbol of impermanence).

Mansfield had experience in the theatre, on stage herself, and though it’s not obvious to a modern audience now, her writing was clearly influenced by stagecraft. (Not obvious now because every writer is influenced by stage craft.) When Edna sees her future, she is imagining the whole thing playing out as if she is watching herself on the stage.

We already know she’s very good at viewing herself like this, because Mansfield introduced her as a girl with an Imaginary Audience at the very beginning of the narrative. Note the melodramatic touches:

How can they add to her suffering like this ? The world is cruel, terribly cruel!

Edna clearly takes delight in her own melancholy.

Unlike grief after the death of someone or something known, melancholy is the feeling you get when you’re grieving for something and you don’t know what that something is.

I wonder if there’s an English or borrowed word for this. Masochism is too strong; schadenfreude only describes taking delight in other people’s misery, and that’s not quite the same even in reverse. For now the best I can say is that Edna has Goth sensibilities. She’s clearly been reading Gothic literature (hence the melodramatic touches and the graveyard and the church…) but I’m talking about the 1970s and 80s Goth now.

A big part of Goth sensibility: Finding pleasure in one’s own melancholy. Another big thing for Goths: rebelling against society’s pressure to conform to gender norms. Imaginatively, Edna would like to rebel in some way. But I doubt she has the imaginative breadth to imagine what true rebellion might look like. Rebelling by escaping to the hugely restrictive institution of the nunnery is a comically ironic thing to fantasise about. Many goths were into death chic (hence the black clothes and white faces). As Edna sits in the graveyard contemplating her own death, yeah, Edna’s sure into death chic. Case closed. Edna is a Goth.

The final paragraph of “Taking The Veil” plunges the reader into that confused space Edna currently occupies: Is there really a family visiting the graveyard crying about their only daughter, or is this part entirely in Edna’s imagination? (Like everything else Mansfield explores, there’s no binary distinction — it could be that Edna sees three people and pastes identities onto them.)

Whether Edna remains alone in the graveyard or not, she experiences another revelation: To break off her engagement with Jimmy would be to wound him forever. She doesn’t have it in her to do that. She will not become a nun. She will make Jimmy happy and become his wife.

NEW SITUATION

Sideshadowing: If Edna were to spend the rest of her life as Sister Angela, I’m sure her sparks of lust and secret fantasies would make the whole thing bearable. For Edna, perhaps the prospect of marrying Jimmy is on a par with the prospect of joining a nunnery. She may expect both situations to be restrictive and physically unsatisfying.

Extrapolation: Since we can never really know how others experience their sexuality, it’s worth pointing out that not everyone’s life is a trajectory towards satisfying penetration within the Sanctity of Heterosexual Marriage. Even after marriage, Edna is just as likely to continue as she is right now, seeking pleasure imaginatively.

FURTHER READING

This theme of secret fantasy life as a means of getting through marriage has been explored by various writers, especially woman writers. One notable example which springs to mind right now: Alice Munro in her short story “Cortes Island“.

The header illustration is by Sir John Everett Millais, Bt The Vale of Rest (1858–9). I’ve chosen it because of the nuns, but also because Mansfield’s story is about a burial — a burial of big, nascently (a)sexual emotions.