Do not allow yourselves to be deluded by the abstract word ‘freedom’. Whose freedom? It is not the freedom of one individual in relation to another, but the freedom of capital to crush the worker.

Marx, On the Question of Free Trade 1848

The American West is more than a place. It’s a super powerful idea. One of those ideas associated with the place: Freedom. Here in Australia, I’ve heard the main cultural difference between Australia and the USA encapsulated like this: Australia aims for equality, America for freedom. Whether that’s a useful and accurate description or not, I don’t know, and freedom is just one of the big ideas around American identity. We might also include: frontier, opportunity, honour, individualism and justice.

But today I will dive into how freedom has been symbolised in literature and storytelling.

AMERICAN SYMBOLS OF FREEDOM

Naturally, emphasis falls on American literature. And pretty much every main object famously associated with the USA symbolises freedom:

- THE STAR-SPANGLED BANNER ― Composed by Frances Scott Key, the Star-Spangled Banner is the national anthem of the United States of America. Each stanza ends with the phrase, “land of the free and home of the brave”. The anthem itself is a symbol of freedom.

- THE WASHINGTON MONUMENT

- THE ROSE ― American’s national flower. It’s only been the national flower since 1986.

- MOUNT RUSHMORE

- THE BILL OF RIGHTS

- THE CONSTITUTION

- UNCLE SAM

- THE WHITE HOUSE

- THE LINCOLN MEMORIAL

- THE AMERICAN FLAG ― The American flag is a symbol of freedom and justice. (The USA isn’t the only country with a flag symbolising freedom.)

- THE STATUE OF LIBERTY ― it’s in the name

- THE LIBERTY BELL ― ditto

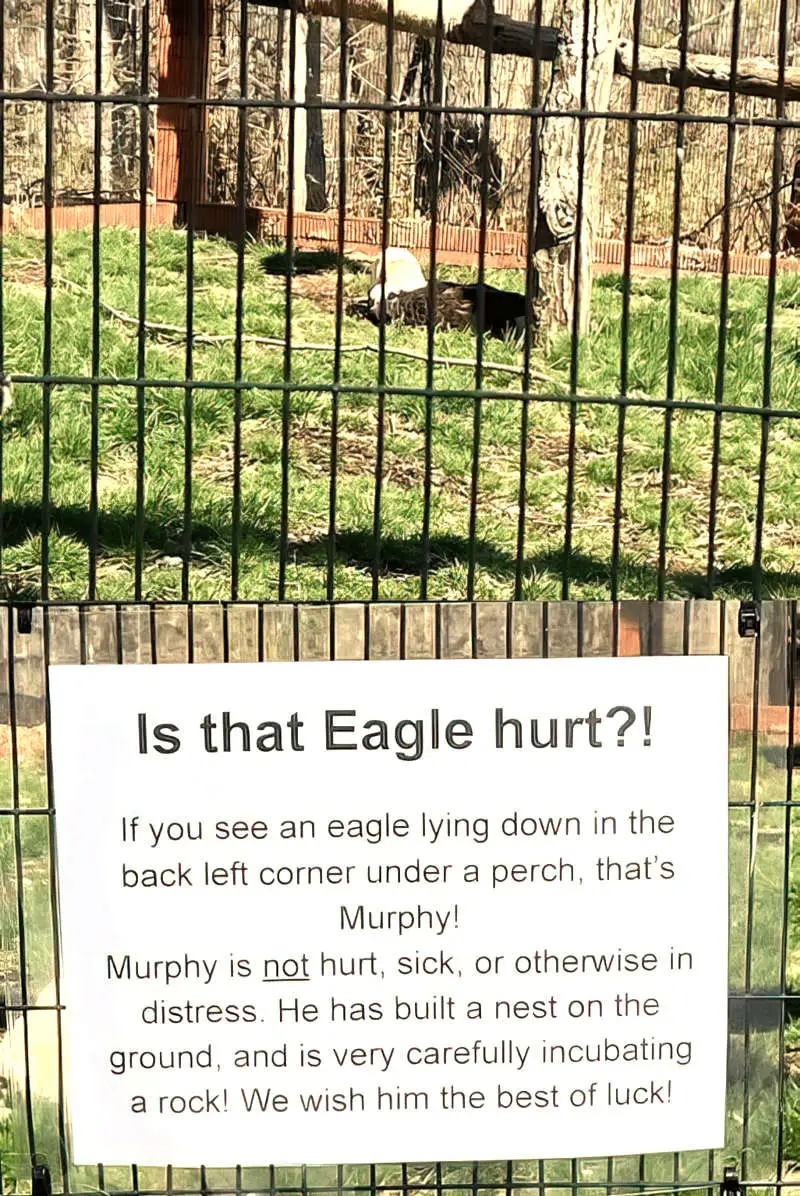

- THE EAGLE ― In the USA, the American Bald Eagle represents freedom. In common with other apex predators such as tigers and wolves, which can also represent freedom, eagles take full charge of their terrain and have no natural predators. It looks pretty good to be an eagle.

- THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE

- THE GREAT SEAL

Essential American freedoms

freedom [is] a word that has been elevated throughout American history to near-theological status.

Sam Tanenhaus, 2010, writing about Freedom by Jonathan Franzen

- Speech

- Worship

- The securities of justice

- The right for people (“men”) to choose their own callings (This doesn’t extend to people who can grow babies, who have have recently lost the right not to be ‘mothers’, or to trans people, who are fighting hard for the right to live in their ‘called’ gender.)

- The freedom to move practically without restriction across frontiers.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN FREEDOM AND LIBERTY

According to The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover, at the dawn of the Armistice (1918), “liberty, freedom and democracy were watchwords of the day”. This suggests freedom and liberty are not the same thing.

Not everyone makes a distinction between these concepts in all contexts, but freedom can mean “the ability to do as one wills and what one has the power to do”. In contrast, “liberty” can mean the absence of arbitrary restraints, and takes into account the rights of all involved.

SOME SYMBOLS OF FREEDOM FROM AROUND THE WORLD

- The Grunwald Swords are a symbol of freedom from the medieval era.

- The Liberty Cap (Papa Smurf’s cap) was a revolutionary symbol in America as well as France. Its original use was as a symbol of freedom from slavery.

- The Berlin Wall was a guarded concrete barrier that encircled West Berlin from 1961 to 1989, separating it from East Berlin and East Germany (GDR). The Berlin Wall has since become a universal symbol of freedom and the struggle against oppression.

- In Mayan culture, one of the sacred symbols was the Quetzal bird. If placed in captivity, the Quetzal will die, which is how it came to represent freedom to the Maya. (Although scientists are able to keep a Quetzal alive and even breed them, in captivity these birds are nothing at all like their free selves.) This symbol has survived Spanish colonisation, and is displayed on Guatemala’s national flag. (The quetzal is also the name of Guatemala’s currency.)

- The Virgin of Guadalupe (“Mother of the Mexicans”) is one image of the Virgin Immaculate which is venerated in Mexico. She is thought to have first appeared on December 8, 1531 on the hill of Tepeyac, north of Mexico City, showing herself to a native man who had just converted to Christianity. Even today, she has overarching political significance. and has become a national emblem. It is often thought that from the 16th century on, Guadalupe served as a symbol of freedom for oppressed native populations. Unfortunately, the image of Guadalupe has been used by various different groups for their own ends. For ruling parties, she was also used to control. Legal documents show that she was used as a mediator between native people and so-called higher (colonial) authorities, both celestial and civil.

- When Ireland was colonised, the art of playing a harp was nearly destroyed. Since then, the harp has become a symbol of freedom.

- Knowledge is power, so the saying goes. Knowledge is also freedom. As an extension of that, libraries function as a symbol of freedom. When it is hard won, education and educational institutions serve as symbols of freedom e.g. for African American families during America’s Jim Crow laws.

- The horse is a symbol of freedom, obviously because it allowed people to travel further than on human foot. (Horses were also a symbol of traditional patriarchal masculinity, conjuring up ideas about male vitality, self-reliance and potency.) The horse as a symbol of freedom was replaced and subsequently the motor vehicle and motorcycle.

- For Black slaves escaping slavery by night, the North Star provided a guide to the true North, and therefore became a symbol of freedom for Black people.

SYMBOLS OF FREEDOM IN LITERATURE

SPACE

Very broadly, space itself represents freedom. Note that, by extension, that other spacious places equal freedom as well: the sky and the ocean/sea.

But space also makes us vulnerable to attack, so space is both a good and a bad thing for us. Note also the distinction between ‘space’ and ‘place’ in the excerpt below:

Space is a common symbol of freedom in the Western world. Space lies open; it suggests the future and invites action.

On the negative side, space and freedom are a threat … Open space has no trodden paths and signposts. It has no fixed pattern of established human meaning; it is like a blank sheet on which meaning may be imposed.

Enclosed and humanized space is place. Compared to space, place is a calm center of established values. Human beings require both space and place. Human lives are a dialectical movement between shelter and venture, attachment and freedom.

In open space, one can become intensely aware of place; and in the solitude of a sheltered place the vastness of space beyond acquires a haunting presence. A healthy being welcomes constraint and freedom, the boundedness of place and the exposure of space.

Yi-Fu Tuan, 1977

FEMINISM, FREEDOM AND SPACE IN “THE YELLOW WALLPAPER”

Until very recently, and continuing into the present, men have had much control over women’s movement through space and place. Literature by women sometimes addresses this imbalance.

In “The Yellow Wallpaper“, the famous late 19th century short story:

For space to be a woman’s…that space has to be defined by men: cultivated and controlled. Riotous flowers and gnarly trees suggest uncultivated, undefined, uncontrolled nature; thus when the narrator in Gilman’s story looks out the window, she sees nature or the wildness as a symbol of freedom, as a place to escape male dominance and control. Here Gilman echoes Henry Thoreau’s romantic (transcendental) notion that “in wildness is the preservation of the world”.

SCHWENINGER, LEE. “Reading the Garden in Gilman’s ‘The Yellow Wallpaper.’” Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, vol. 2, no. 2, 1996, pp. 25–44.

AMERICAN SPACE IN JONATHAN FRANZEN’S NOVEL FREEDOM (2010)

More than a century later, American author Jonathan Franzen wrote Freedom, which obviously does a lot with… symbols of freedom. Is freedom a good thing or a bad thing for the characters?

[The main characters] are as cursed as they are blessed by a surfeit of freedom.

Rodney Clapp, writing about Freedom by Jonathan Franzen

In American literature―including Freedom, including The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1925), travel towards specific cardinal directions (east and west) have a specific meaning with regards to freedom:

[R]eviewers have probably not stressed strongly enough that freedom is just one dimension of a more general theme whose mythical possibilities and contradictions are exampled by both Fitzgerald [in The Great Gatsby] and Franzen though the movement of their characters between the East and the West of the United States: the multifaceted, everlasting myth of the American Dream.

The Great Gatsby deals mainly with two dimensions of the Dream, the strictly material dimension of making money, and a more spiritual dimension, which for Gatsby involved his search for eternal youth, the possibility of recapturing his and Daisy’s past.

Franzen deals with the material dimension as well (as exemplified by Joey), but he also explores the implications of the concept of freedom as part of the American Dream: “People come to this country for either money or freedom. If you don’t have money, you cling to your freedoms all the more angrily“.

Jenna’s father associates the word with immigration and offers the more conventional view of the myth: “My great-grandfather … came over here with nothing. He was given an opportunity in this country, which gave him the freedom to make the most of his abilities. That’s why I’ve chosen to spend my life the way I have―to honor that freedom and try to ensure that the next American century be similarly blessed“.

Walter, in turn, offers a more critical interpretation: “the American experiment of self-government [was] statistically skewed from the outset, because it wasn’t the people with sociable genes who fled the crowded Old World for the new continent; it was the people who didn’t get along with the others”, and later, “the personality susceptible to the dream of limitless freedom is a personality also prone, should the dream ever sour, to misanthropy and rage”. When the dream sours, Walter states: “You may be poor, but the one thing nobody can take away from you is the freedom to fvck up your life whatever way you want to“.

González, Jesús Ángel. “Eastern and Western Promises in Jonathan Franzen’s ‘Freedom’ / Promesas Del Este y Del Oeste En ‘Freedom’, de Jonathan Franzen.” Atlantis, vol. 37, no. 1, 2015, pp. 11–29.

BIRDS

Sometimes specific birds represent freedom (c.f. the American Bald Eagle, the quetzal), but birds in general are a symbol of freedom. Wings afford birds the ability to travel great distances, so migratory birds are especially well-suited as a symbol of freedom. Feathers on their own can also represent freedom.

In contrast, a caged bird represents entrapment.

Anything associated with travel through the sky can be considered a symbol of freedom, including the sky itself. Blue is the colour most frequently associated with freedom.

I sometimes wonder whether the act of surrender is not one of the greatest of all – the highest. It is one of the [most] difficult of all… You see it’s so immensely complicated. It needs real humility and at the same time, an absolute belief in one’s own essential freedom. It is an act of faith. At the last moments, like all great acts, it is pure risk. This is true for me as a human being and as a writer. Dear Heaven, how hard it is to let go – to step into the blue. And yet one’s creative life depends on it and one desires to do nothing else.

Katherine Mansfield, Katherine Mansfield Letters And Journals: A Selection

See: What do birds symbolise in literature?

THE SKY

Birds are symbols of freedom partly because of their ability to fly in the sky, but does that mean anything in the sky is a symbol of freedom?

Well, no. Clouds, like mirages, seem in reach but the closer you get the more unreachable they seem. Ergo, clouds and their shadows offer only a distant, unattainable mirage of freedom.

WINDOWS

In the short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892), the confined wife looks out the window to the garden and space beyond. The freedom outside juxtaposes against the wife’s containment in her barred room.

For more on the role windows play in narrative see: The Symbolism of Windows. In children’s stories, characters frequently contemplate an adventure outside the home by first gazing from a window.

FENCES

Also especially in children’s stories, characters swinging on gates or sitting on walls looking to the wider world beyond the domestic sphere indicate the beginning of adventure. Gates and walls around houses are designed to be traversed.

Note that in “The Yellow Wallpaper,” the garden immediately outside is a garden of gates, locks and hedges. This is tamed wilderness, which maps onto ‘wife’. The wilderness beyond maps onto ‘woman’. (Woman who has not been tamed as somebody’s complacent, dutiful wife.) So long as the confined wife in “The Yellow Wallpaper” makes no distinction between garden and nature, the (overgrown) garden she sees from her window offers the hope of freedom.

See: Fences, Gates and Walls In Art And Storytelling

WILDERNESS

To the traditional moralists, the “forest,” or “wilderness,” or “uncivilized Nature” was the symbolic abode of evil―the very negation of moral law. But to the romantics, wild nature had become the very symbol of freedom.

Carpenter, Frederic I. “Scarlet a Minus.” College English, vol. 5, no. 4, 1944, pp. 173–80.

Wilderness as a symbol of freedom works best when conveyed in conjunction with a tamed garden.

Often punctuated by a fence, hence the connection, the wilderness (as opposed to the manmade symbolic equivalent of the garden) is often a symbol of freedom in stories. Gardens imply confinement. (Again, see this at play in “The Yellow Wallpaper”.)

Gardens don’t always symbolise confinement. (See The Secret Garden, for example.) But in general, without subversion, people create gardens in an attempt to tame wilderness and nature. The corollary: Domination of gardens as metaphor for the domination and control of people.

The garden is a representation of nature that masquerades as a mimesis of what it represses but which is really a total reconstruction of what is repressed.

Simon Pugh, Garden-nature-language, 1988.

“Solitude increased my perception. But here’s the tricky thing: when I applied my increased perception to myself, I lost my identity. There was no audience, no one to perform for. There was no need to define myself. I became irrelevant. (I)solation felt more like communion…To put it romantically, I was completely free.”

Michael Finkel, The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit

THE SEA

If the wilderness is a symbol of freedom, what is the ultimate wilderness (here on Earth)? The sea! The sea can be divided into two distinct places: The surface and the deep (the ocean).

The sea means total freedom: unharnessed, uncontrolled, omnipotent, omnipresent.

If a character runs to the sea and stands on the beach looking out, it’s likely they’ve experienced a self-revelation which will allow them to live with more freedom going forward.

See: Ocean Symbolism In Storytelling

MADNESS

Sometimes characters only attain freedom by finding it in madness. This applies to the narrator of “The Yellow Wallpaper”.

FREEDOM AND CHARACTER ARCS

Characters are obliged to act according to the laws of the world in which they live. In other words, the narrator is the prisoner of his own premises.

Umberto Eco, Postscript to the Name of the Rose

In stories, characters change. The change may be tiny; it may be massive. Apart from the degree of change, there is another way of thinking about a character’s freedom: Do they end up more free at the end than they were at the beginning?

Yuval Noah Harari writes in 21 Lessons For The 21st Century that all stories are basically about the victory of mind over matter. Howard Suber says something similar in his book on film: That every movie could be called ‘Trapped’.

Is it true that in every single story, a character is gets stuck somewhere?

Erich Fromm, in The Forgotten Language, explains that there is a ‘manifest’ and a ‘latent’ layer to most stories. This is the terminology Freud used when describing dreams.We might call them ‘literal’ and ‘symbolic’ layers, except Fromm’s terminology is better — in a story like Jonah and the Whale, the ‘literal’ layer has its own weird logic, so it feels a bit weird to call it ‘literal’. When Jonah can’t stand it inside the whale and starts praying to God for release, this is a plot point characteristic of neurosis.

An attitude is assumed as a defense against a danger, but then it grows far beyond its original defense function and becomes a neurotic symptom from which the person tries to be relieved. This Jonah’s escape into protective isolation ends in the terror of being imprisoned, and he takes up his life at the point where he had tried to escape.

Erich Fromm

Home is not where you are born. Home is where all your attempts to escape, cease.

Naguib Mahfouz

In Breaking Bad there is a character who Walter White pays to go to prison in his place. For this other guy, prison is its own kind of freedom — freedom from the worries of the outside world. Jimmy “In-‘N-Out” Kilkelly has become institutionalised, which means he understands prison laws better than he understands society’s laws. All characters desire freedom, including “In-‘N-Out” Kilkelly. Another example of someone who seems to crave imprisonment is the main character in King Rat, but again, that’s only because he has ironically found his own kind of freedom within the workable constraints of imprisonment.

- The Onion recently lampooned this human tendency to crave trammels.

- Writers sometimes do very well with trammels. Unleashed creativity is a sprawling, scary thing.

While others talk about being ‘trapped’ and ‘victory of mind over matter,’ ‘victory of mind over matter’ is also a type of ‘freedom’. As noted above by others, Most stories move a character from entrapment to freedom. This is especially true of children’s stories.

However, not all stories have happy endings. In life as in fiction, not everyone ends up free.

There are two kinds of freedom: positive and negative liberty, or “freedom to” and “freedom from.”

Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex by Angela Chen

You’ll miss your freedom.

E.B. White, Charlotte’s Web

We in this room have no private properties. Perhaps one or two of us may own the homes we live in, or have a dollar or two set aside – but we own nothing that does not contribute directly toward keeping us alive. All that we own is our bodies. And we sell our bodies every day we live. We sell them when we go out in the morning to our jobs and when we labor all day. We are forced to sell at any price, at any time, for any purpose. We are forced to sell our bodies so that we can eat and live. And the price which is given us for this is only enough so that we will have the strength to labor longer for the profits of others. Today we are not put up on platforms and sold at the courthouse square. But we are forced to sell our strength, our time, our souls during almost every hour that we live. We have been freed from one kind of slavery only to be delivered into another. Is this freedom? Are we yet free men?”

Carson McCullers, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter

THE THREE MAIN TYPES OF ENTRAPMENT STORYLINES

There are three main ways characters move between entrapment and freedom in stories, with complicated variations on these.

1. Entrapment to Further Entrapment to Freedom

Shawshank Redemption is a standout example of the Entrapment to Greater Entrapment to Freedom arc. Heartwarming stories will take a character along this particular journey.

2. Entrapment to Greater Entrapment to Death

The character never breaks free. They may descend into madness.

No law requires art to be “pleasing.” A story that raises expectations, then shows why they can neither be satisfied nor denied, can be as illuminating.

John Gardner, The Art of Fiction: Notes on Craft for Young Writers

The lyrics of “Flow” by Crooked Colours describe a certain psychological entrapment, often brought on by love:

“I took off from paradise

And I landed in the jungle…”

Hamlet is the standout example of this arc, and is therefore a tragedy. Yuval Noah Harari describes how The Lion King is a modern Hamlet:

The 1994 Disney epic The Lion King repackaged this ancient story for modern audiences, with the young [WEAKNESS] lion Simba standing in for Arjuna. When Simba wants to know the meaning of existence [DESIRE], his father — the lion king Mufasa — tells him about the great Circle of Life. Mufasa explains that the antelopes eat the grass, the lions eat the antelopes, and when the lions die their body decomposes and feeds the grass. This is how life continues from generation to generation, provided each animal plays its part in the drama. Everything is connected, and everyone depends on everyone else, so if even a blade of grass fails to fulfil its vocation, the entire Circle of Life might unravel. Simba’s vocation, says Mufasa, is to rule the lion kingdom after Mufasa’s death, and keep the other animals in order.

However, when Mufasa is prematurely murdered by his evil brother Scar, young Simba blames himself for the catastrophe, and racked with guilt [ENTRAPMENT] he leaves the lion kingdom, shuns his royal destiny, and wanders off into the wilderness. There he meets two other outcasts, a meerkat and a warthog, and together they spend a few carefree years off the beaten path. [MYTHIC JOURNEY] Their antisocial philosophy means that they answer every problem by chanting Hakuna matata — no worries.

But Simba cannot escape his dharma. As he matures, he becomes increasingly troubled [GREATER ENTRAPMENT], not knowing who he is and what he should do in life. At the climactic moment [BIG STRUGGLE] of the movie, the spirit of Mufasa [ALLY] reveals himself to Simba in a vision, and reminds Simba of the Circle of Life and of his royal identity. Simba also learns that in his absence, the evil Scar [OPPONENT] has assumed the throne and mismanaged the kingdom, which now suffers greatly from disharmony and famine. Simba finally understands who he is and what he should do [ANAGNORISIS]. He returns to the lion kingdom, kills his uncle, becomes king, and re-establishes harmony and prosperity. The movie ends with a proud Simba presenting his newly born heir to the assembled animals, ensuring the continuation of the great Circle of Life [NEW SITUATION].

So, in repackaging Hamlet for contemporary kids, Disney turned the story into a happy one, with the Freedom to go forth and keep building family at the end.

But apparently, this is how The Lion King almost ended.

Sometimes, however, death is meant to be a freedom in itself. “The Little Match Girl” broke my heart as a preschooler, but I didn’t live in an 1800s culture in which death is meant to be better than living a life of poverty. Andersen meant her hypothermic death as a happy ending because the little girl got to see her grandmother again in Heaven.

Even today, some cultures would consider death a type of freedom.

3. Entrapment to Temporary Freedom to Greater Entrapment or Death

If you want to create a heartbreaking drama, bloody hell, use this one.

The Wrestler fits in here. I find this arc even more tragic than the arc of a tragedy like Hamlet, because we had a glimpse of how Randy’s life might have looked had he made different choices. He was so close to achieving a lasting relationship with Stephanie and with Pam. If only he hadn’t blown it. If only. This arc invokes the strong emotion of regret.

In the temporary freedom phase, there will very often be some flight symbolism to show the audience how great things could be.

FREEDOM AND HAPPINESS ARE TWO DIFFERENT THINGS

…It would be a violation of progressive politics if you don’t pay your babysitter a living wage. I don’t think it is a violation of progressive politics if you as a woman are the one who makes your kids’ babysitting schedule. I think those are two different things.

Q: For me the question of sexual empowerment is a question of freedom versus happiness. It seems a goal of pro-sexual freedom is so that people can have a sex life of their own making, which is freedom. Then there’s a separate idea, which I don’t think either of you are embracing, but I feel like it’s unspoken in our culture, which is that if you do all of these things you’ll be happy. But I actually think your ability to do something is separate from your happiness doing it. Pro-sex feminism does not owe you good sex, just like marriage equality does not owe you a good marriage. Is it possible to divorce the two ideas from each other, that being able to do something is different from enjoying that thing? Is bad sex the price we pay for those choices?

A: I think you at any point in history could be in a relationship with a god-awful person. In fact it was much more likely that you would be in a relationship with a god-awful person fifty years ago when women had far fewer options and were far more stigmatised for being single. So let’s just clear that up. I don’t think that sex is getting worse. What I think is that there’s a bigger gap between our expectations for sex and relationships and the stubbornly bad sex and relationships that we’re still having. I think we have all this info, these resources, all this “empowerment”, and yet we’re still seeing some of the same patterns.

After Dobbs: What Is Feminist Sex?, The Argument, NYT, Wednesday 28 September 2022

RELATED

If you listen to the theologian and philosopher St Augustine, real freedom doesn’t mean the right to do anything whatsoever. It means being given access to everything that is necessary for a flourishing life — and, it follows, being protected from many of the things that ruin life.

Alain de Botton, here

Scientific Evidence That You Probably Don’t Have Free Will from io9

What Does It Really Mean To Be Free and Equal? — A talk by Ayaan Hirsi Ali

CASE STUDIES OF FREEDOM SYMBOLISM IN LITERATURE

HOUSE OF SPIRITS

House of the Spirits is the first novel of Isabel Allende, published 1982.

Each main woman character in the story is allegorical, and represents a different way of fighting for freedom and equality.

- Nivea: represents the early suffragist movement

- Clara: a strong, wilful woman who personalises women’s fight for liberty. Clara partly achieves freedom not by going mad but by escaping into her imagination, either by reading books or imagining herself far away. In this way, she builds a home for herself, and only herself, in her own head.

- Blanca: continues the tradition of independence started by her grandmother. Blanca epitomizes women at a certain time in Chilean social and political history. She doesn’t rally for suffrage but does defy her controlling father by leaving his home.

- Alba: the same allegorical use as Blanca, but in a different era. Alba goes one step further than her mother and leads her lover Miguel through the garden of ‘the big house on the corner’. As in other stories such as “The Yellow Wallpaper”, the garden in this story is a symbol of freedom. This couple recreates the house to suit themselves.

As a girl, Clara del Valle can read fortunes, make objects move as if they had lives of their own, and predict the future. Following the mysterious death of her sister, Rosa the Beautiful, Clara is mute for nine years. When she breaks her silence, it is to announce that she will be married soon to the stern and volatile landowner Esteban Trueba.

Set in an unnamed Latin American country over three generations, The House of the Spirits is a magnificent epic of a proud and passionate family, secret loves and violent revolution.

In this episode of Talk Nerdy, Cara is joined by the author of “The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote,” Elaine Weiss. They talk about the fascinating history of women’s suffrage, including the brave individuals who fought against misogyny, racism, and corporate interests to secure the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

THE SCARLET LETTER

Wilderness equals freedom, and for idealistic heroine Hester Prynne in The Scarlet Letter, is not presented as a good thing for her. Remember, the romantics linked untamed nature with freedom:

Hawthorne explicitly condemned Hester for her wildness―for “breathing the wild, free atmosphere of an unredeemed, unchristianized, lawless region.” And again he damned her sympathy” with “that wild, heathen Nature of the forest, never subjugated by human law, nor illlumined by higher truth.” Clearly he hated moral romanticism. And this hatred would have been harmless, if his heroine had merely been romantic, or immoral.

But Hester Prynne, as revealed in speech and in action, was not romantic but transcendental. And Hawthorne failed utterly to distinguish, in his moralistic criticism, between the romantic and the transcendental. For example, he never described the “speculations” of Hester concerning “freedom” as anything but negative, “wild,” “lawless,” and “heathen”. All “higher truth” for him seemed to reside exclusively in traditional “civilized” morality. But Hawthorne’s contemporaries, Emerson and Thoreau, had specifically described the “wilderness” (Life in the Woods) as teh precondition of the new morality of freedom; and “Nature” as the very abode of “higher truth”: all those transcendental “speculations” which Hawthorne imputed to his heroine conceived of “Nature” as offering the opportunity for the realization of the higher moral law and for the development of a “Christianized” society more perfectly illumined by divine truth.

Carpenter, Frederic I. “Scarlet a Minus.” College English, vol. 5, no. 4, 1944, pp. 173–80.

The essay goes on to say that ‘almost in spite’ of the guy who created her in a book, Hester is able to envision ‘the transcendental ideal of positive freedom, instead of the romantic ideal of mere escape’. She and her lover created a new life in the wilderness.

Of all Hawthorne’s novels, Hester Prynne managed to embody the American Dream of freedom. However, Hawthorne didn’t create Hester’s freedom on an intellectual level. The freedom she achieves happens only at an emotional level. The author seemed to make sure that later heroines weren’t accidentally more sympathetic than he wanted them to be.

INVISIBLE MAN

Black writers have particular reason to critique the freedom afforded by the American Dream and we see this done in Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison (1952):

Barbara Christian sees…recreation of the self in metaphorical and metonymic terms: “Ellison had devised a plan for a book which would incorporate the myth and literature of the Western World into the experience of the American black man.” Hortense Spillers finds this mythical retelling possible with Invisible Man as “confessor” on “a historical line that reaches back through the generations and extends forward into the frontiers of the future.” I take this further to suggest that the “historical line” is encoded with archetypal figures which bear witness to the narrator’s tale. The women who bear witness to the “beingness” of the Invisible Man work as metaphors of cultural consciousness. They sustain him during his dizzy spells at various times in the street and during allt he dream excursions that explain the mystery of surviving being-black-in-the-world. The archetype and the disembodied voice taken together are the figurative conscience of America. As such, they are both a mediating force and a signifying trope parodying the American Dream.

Fonteneau, Yvonne. “Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man: A Critical Reevaluation.” World Literature Today, vol. 64, no. 3, 1990, pp. 408–12.

Most critiques of The Invisible Man have been done by men. But some, e.g. by Claudia Tate, address the treatment of women in this novel. The women are by and large one-dimensional figures who assist the Invisible Man along his course to freedom. They serve as ‘teachers’.

One must be careful to acknowledge that the Invisible Man has been formally and culturally indoctrinated to have ambivalent feelings about women. […]

Agonizing over the sexual roles he is expected to play [The Invisible Man] queries, “Why do [white males] have to mix their women into everything?” He realises that “between us and everything we wanted to change in the world they placed a woman: socially, politically, economically”. The prediction of the mad veteran on the train comes true; the only “freedom” he has known has been “symbolic”. Time after time he finds that the most easily accessible symbol of “freedom” is “woman”. Although woman discloses the trace, revealing the source of illusions and violence, as a construction of ideology she too is an illusion.

Fonteneau, Yvonne. “Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man: A Critical Reevaluation.” World Literature Today, vol. 64, no. 3, 1990, pp. 408–12.

FREEDOM: RELATED TERMS

CAPTIVITY NARRATIVE

A story about colonials or settlers captured by Amerindian or aboriginal tribes and live among them for some time before gaining freedom. These are often autobiographical. Example: A Narrative of the Captivity and Restauration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson. This late 17th century story is about how Mary was captured by Indians and had to live with the Wamanoag tribe. There are also fairytale examples, for instance the category of fairytales about wild bears who have a child with a woman. For more on that see my post on “Cortes Island” by Alice Munro and scroll down to the bottom, because Munro’s modern short story has a basis in North American fairytale.

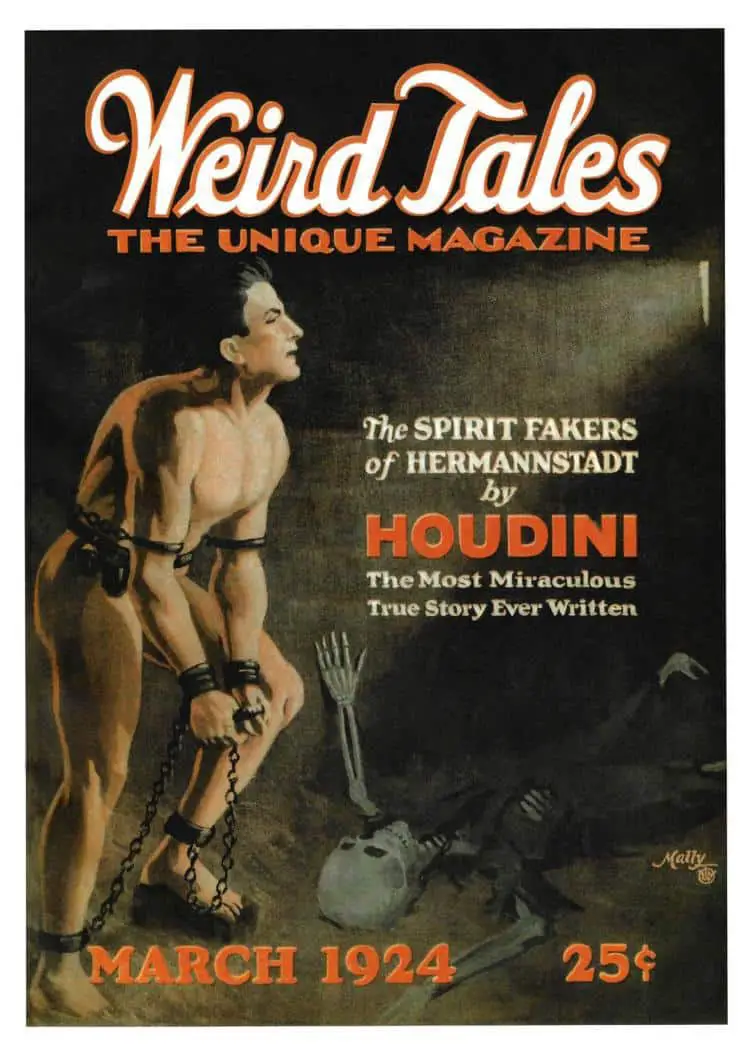

ESCAPE LITERATURE or LITERATURE OF ESCAPE

Describes stories about desperate characters escaping from confinement. POW camps of the First and Second World Wars are common settings. These stories make use of the narrative techniques of suspense and psychological horror. Examples: The Tunnellers of Holzminden by H.G. Durnford, The Wooden Horse by Eric Williams. Any story about escape falls under the broad category of escape literature. Further examples: Stephen King’s novella “Rita Hayworth” by Stephen King, Shawshank Redemption, also by Stephen King, The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexander Dumas, part one.

SLAVE NARRATIVE

A story about a slave’s life. The slave narrative has been called “the trope of tropes”. Commonly includes the capture, punishments, daily enslavement, and ends with the escape to freedom. Like literature of escape, it is commonly the story of one’s own life. Examples: Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Oroonoko by Aphra Behn, the work of Frederick Douglass.

FREEDOM QUOTES

I am free and that is why I am lost.

Franz Kafka

There is more than one kind of freedom… Freedom to and freedom from. In the days of anarchy, it was freedom to. Now you are being given freedom from. Don’t underrate it.

Margaret Atwood

We must live with the ambiguity of partial freedom, partial power, and partial knowledge. All important decisions must be made on the basis of insufficient data. Yet we are responsible for everything we do.

Sheldon Kopp

It was better to be in a jail where you could bang the walls than in a jail you could not see.”

Carson McCullers, The Member of the Wedding

What I have come to learn after many years of studying, thinking and writing about power and oppression is that there will always be factions of marginalized people who do not want collective liberation from the oppressive systems we live and die under.

Sherronda J. Brown, Refusing Compulsory Sexuality: A Black Asexual Lens on Our Sex-Obsessed Culture

If you don’t accept that bodily autonomy is an essential unconditional liberty, it’s a waste of time talking to you at all. No other liberties survive without that one, more fundamental than property rights: if you don’t own yourself absolutely, you own nothing.

@ScavengerEthic

I’ll tell you what freedom means for me: No Fear.

Nina Simone

I’ve never been free in my whole life. Inside I’ve always chased myself. I’ve become intolerable to myself. I live in a lacerating duality. I’m seemingly free, but I’m a prisoner inside of me.

Clarice Lispector, from A Breath of Life, 1978

PH.S.: Do you think that in your [short] stories you have room to develop a true character, do you think the characters of a short story have the same vital energy as the characters in a novel? Have they got the same requirements as far as the writer is concerned?

V.S.P.: [Short stories] have a very different requirement [from novel length works]. For instance, a full‑length portrait in a novel by Tolstoy of Prince Andrew may only appear in a novel. It is intricately examined. It is examined morally, socially, with a good deal of detail, because such writers are generally describing not simply individuals but a state of society in which they live. And doing so, how they evolve from this society, or escape from it.

V.S. Pritchett interview

I think people would be happier if they admitted things more often. In a sense we are all prisoners of some memory, or fear, or disappointment—we are all defined by something we can’t change.

Simon Van Booy

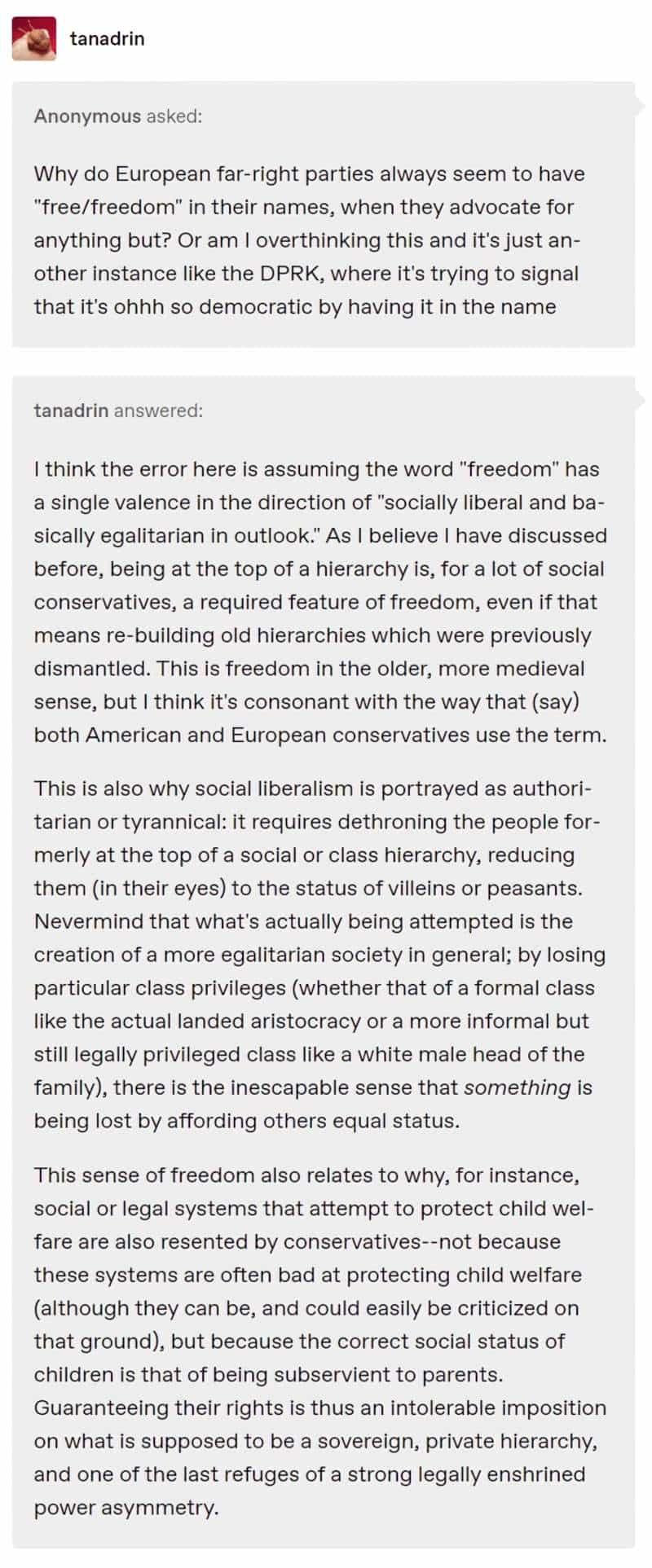

THE FAR RIGHT MEANING OF FREEDOM IS DIFFERENT FROM THE LEFT

THE REACTIONARY MIND BY COREY ROBIN

In The Reactionary Mind, Robin traces conservatism back to its roots in the reaction against the French Revolution. He argues that the right was inspired, and is still united, by its hostility to emancipating the lower orders. Some conservatives endorse the free market; others oppose it. Some criticize the state; others celebrate it. Underlying these differences is the impulse to defend power and privilege against movements demanding freedom and equality — while simultaneously making populist appeals to the masses. Despite their opposition to these movements, conservatives favor a dynamic conception of politics and society — one that involves self-transformation, violence, and war. They are also highly adaptive to new challenges and circumstances. This partiality to violence and capacity for reinvention have been critical to their success.