A veil symbolises a separation. The separation might be:

- between two states of being (e.g. married and unmarried)

- between physical objects

- between concepts

Veils are typically made from diaphanous material. At first glance the nature of the separation appears flimsy. Importantly, the separation is two-directional.

‘To believe in [a ghost] is to believe not only have the dead the power to make themselves visible after there is nothing left of them, but that the same power inheres in textile fabrics’

Ambrose Bierce,The Devil’s Dictionary (1906)

In Bridport Museum in Dorset is a haunted dress, dating back to the Edwardian period, and mysteriously left at the museum door in a bag during the 1960s. Using this artefact as a starting point, this paper will ask what it means for a dress to haunt, or be haunted. As the above quote by Ambrose Bierce suggests, clothes are intimately related to our cultural understanding of the ghostly. From the white sheet that comprises the child’s Hallowe’en costume, to the period costume that authenticates historicity, spectres are subject to particular sartorial traditions and conventions.

Catherine Spooner

VEILS IN FOLKTALES

The following is from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman, 1966. Read through these story summaries and you’ll get a good idea of how coats have been used throughout history. Can you see patterns?

- Veils of fire and ice before chief door of heaven.

- Why women wear veils in India.

- Magic veil.

- Magic veil changes enmity into peacefulness.

- Magic veil renders invisible.

- Magic veil protects from attack.

- Magic veil keeps man from sinking in water.

- Saint‘s veil quells volcano.

- Holy water destroys veil over well.

- Image of Virgin veils and unveils itself.

- Evil eye covered with seven veils.

- Ishtar unveiled. Goddess going to lower world passes through seven gates, at each of which she is divested of a garment till she is entirely unclothed.

- Water-maidens have long veil.

- Woman’s beauty shows through seven veils.

- Identification by veil.

- Veil as chastity index. Flowers on veil fade on head of unchaste.

- Test: to guess which of veiled sisters has golden hair.

- Husband duped by paramour into taking his wife to him. She is veiled.

- Disguise by veiling face.

- Veiled adulteress flees with paramour who has enlisted duped husband‘s aid.

- Bird carries off jeweled veil with which girl had covered sleeping lover‘s face. Lover pursues bird and becomes separated from the girl.

- Woman veils self as expression of surprise.

- Birth with veil brings luck.

- Angels set heavenly veil upon head of pious woman.

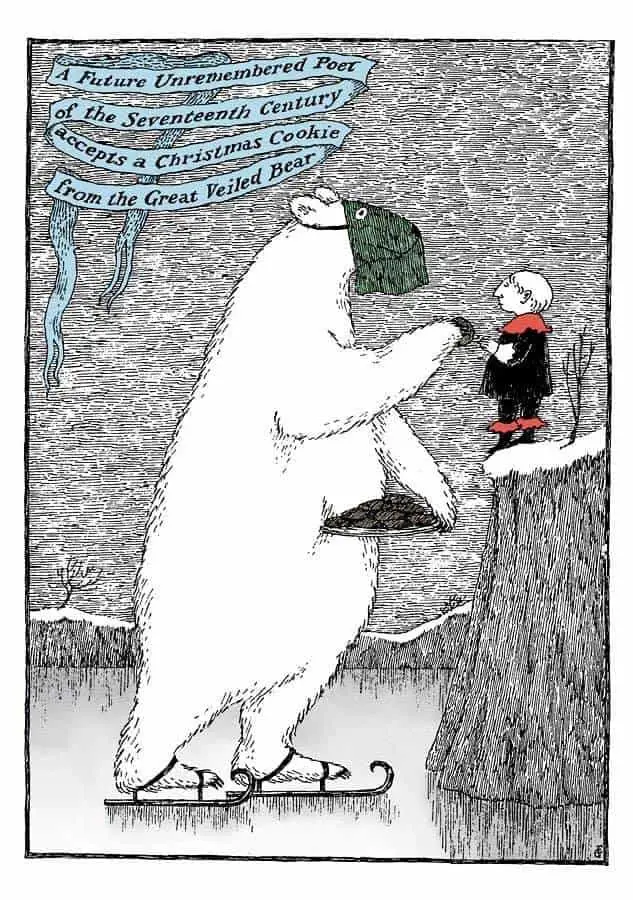

Veil as Thin Border Between Worlds

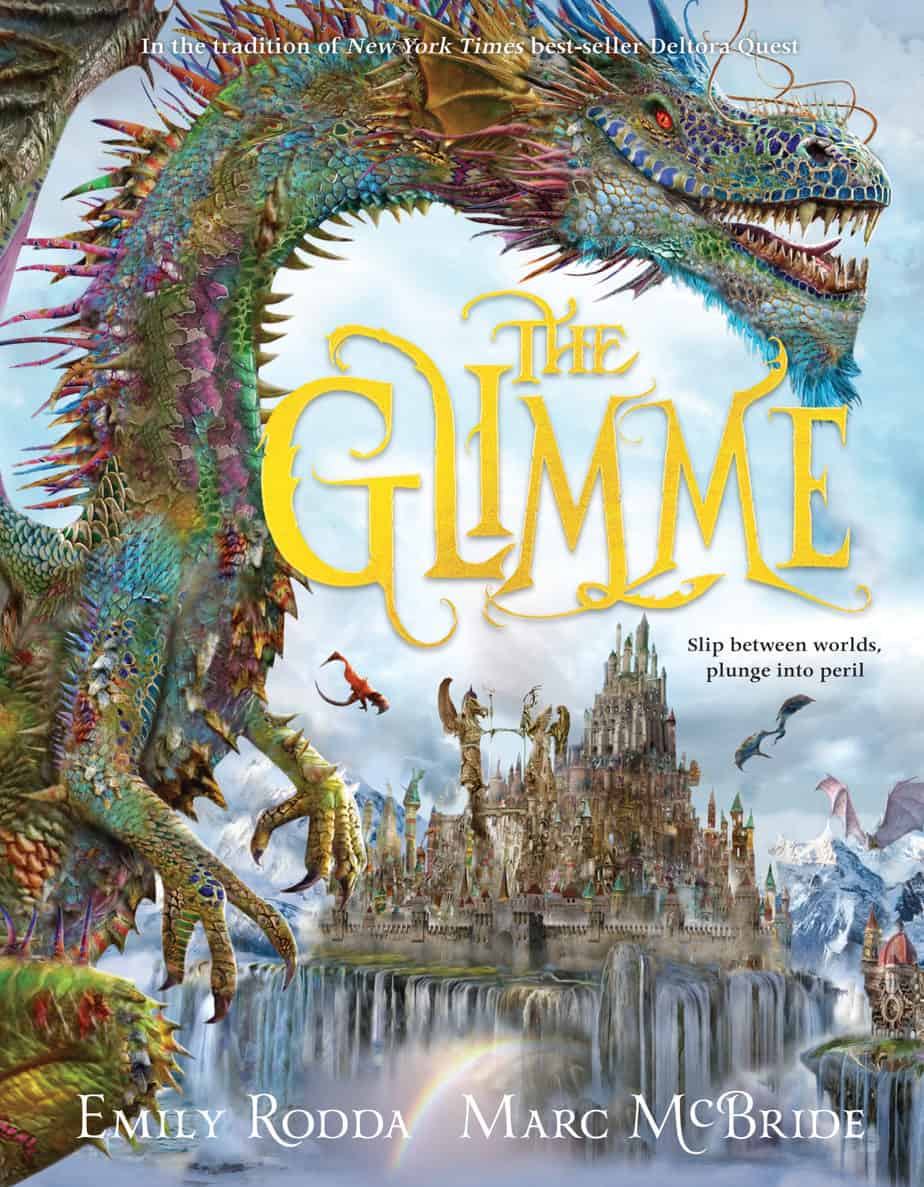

Lone Annie sees dragons in your future. She sees giants. She sees fire and water. She sees death.

Finn’s life in the village of Wichant is hard. Only his drawings of the wild coastline, with its dragon shaped clouds and headlands that look like giants, make him happy.

Then the strange housekeeper from a mysterious clifftop mansion sees his talent and buys him for a handful of gold and then reveals to him seven extraordinary paintings. Finn thinks the paintings must be pure fantasy: such amazing scenes and creatures cannot be real!

He is wrong. Soon he is going to slip through the veil between worlds and plunge into the wonders and perils of The Glimme.

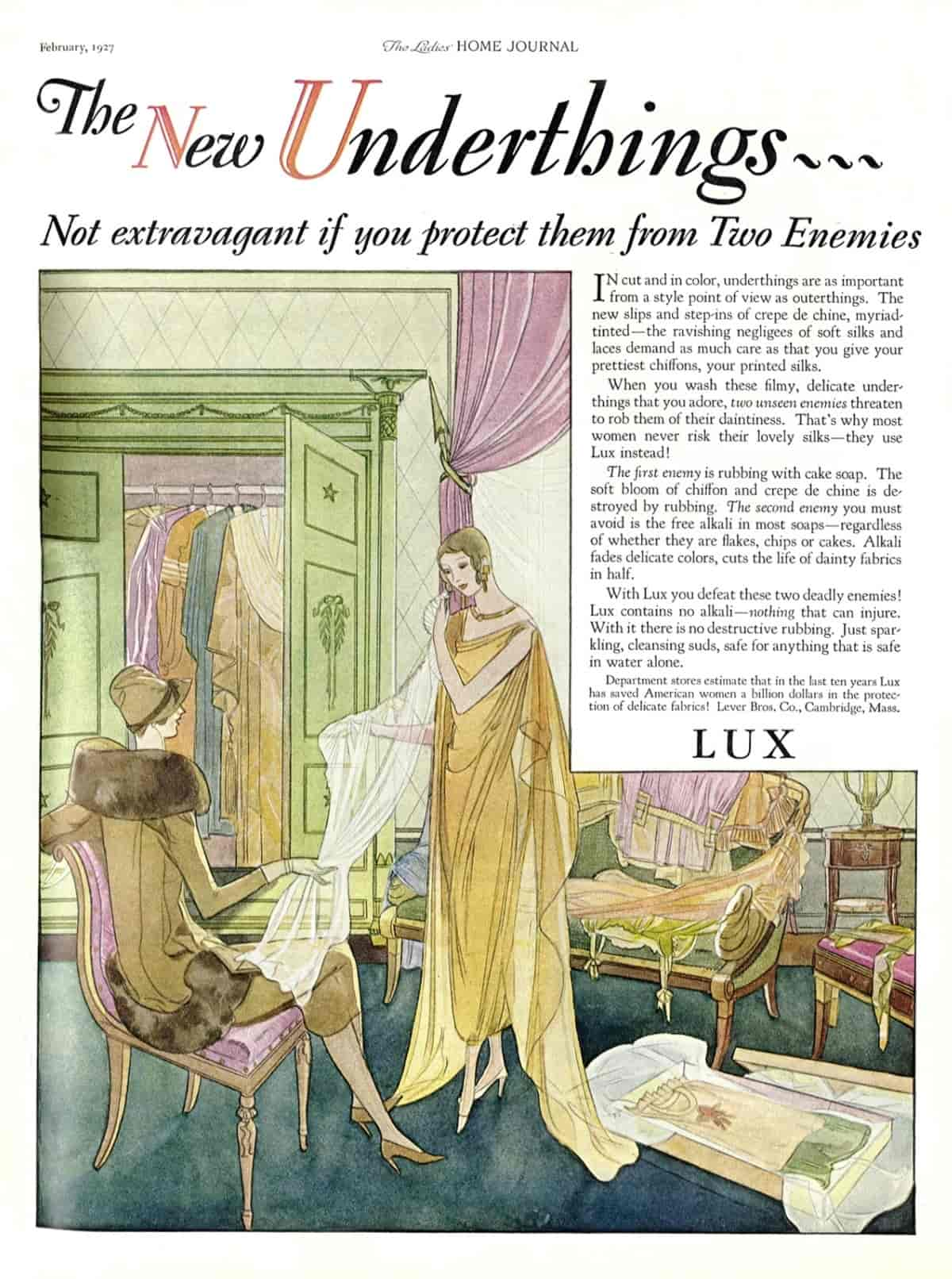

Veil as both ‘revealing’ and ‘hiding’

The word ‘revelation’ comes from Latin revelatio, which means to draw back the veil. Hidden knowledge is often said to be ‘veiled’. These two functions highlight what is easy to miss about the symbolism of the veil: It means two quite different things at once. Symbols are commonly ‘multivalent’, meaning they have multiple applications, interpretations, meanings and values.

Let’s take the example of a nun. Crucially, a nun who ‘takes the veil’ to become a Bride of Christ is removing herself from the world, but she is also removing the world from herself.

Perhaps this same symbolism holds in marriages between flesh-and-blood people, though the veil as marriage symbol does differ somewhat. These days the veil is often simply a wedding accoutrement, but across cultures, marriage veils traditionally symbolise patriarchal claims on women as wives.

In a crystal clear example of misogyny, the Greek word for veil is ‘hymen’. Historically, the lifting of the bride’s veil at a wedding symbolises the tearing of the hymen on her wedding night. (The hymen does not in fact ‘tear’ but ‘stretches’ and makes for terrible proof of virginity, in turn a terrible concept.)

There’s another item of clothing/costume with a dual purpose, and which also hides the face. You guessed it; it is the mask, seen clearly on a character such as the Harlequin. The Harlequin’s mask is about:

- the sacred

- the profane

Maybe this duality of masks functioning in two opposite ways seems like an enigma, until we accept the fact that humans are perfectly capable of holding onto two contradictory beliefs at the same time.

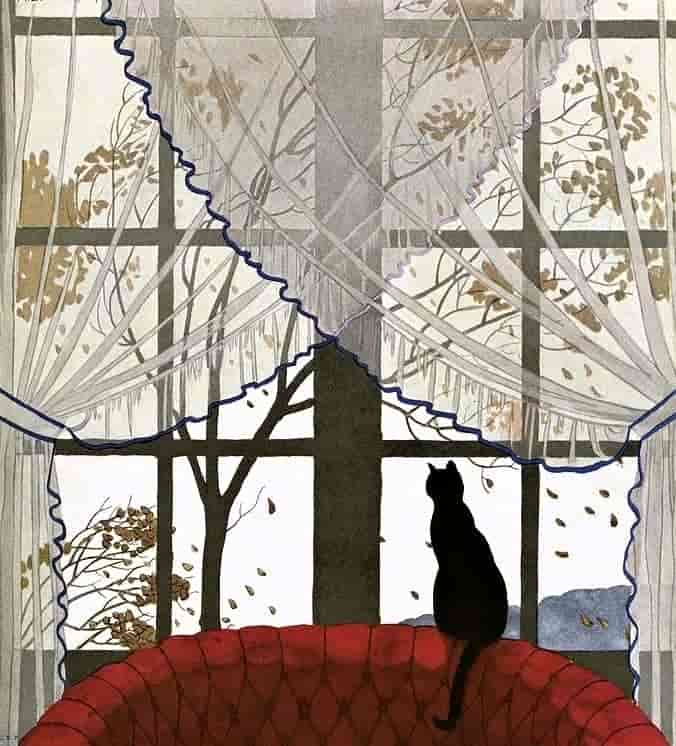

I believe the following passage helps to explain the meaning of Kenneth Grahame’s title The Wind In The Willows:

In midmost of the stream, embraced in the weir’d shimmering arm-spread, a small island lay anchored, fringed close with willow and silver birch and alder. Reserved, shy, but full of significance, it hid whatever it might hold behind a veil, keeping it till the hour should come, and, with the hour, those who were called and chosen.

Kenneth Grahame, The Wind In The Willows, “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn”.

Of all the trees, the willow feels most like a hidden room, with its drooping branches. In this way, the willow tree conceals, except, of course, when the wind blows. Then, and only then, are you revealed a little to the outside world. The Wind In The Willows is full of masking and unmasking motifs.

In The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett, ‘ivy trails’ function in a similar way, keeping hidden the door to the walled garden. Mary Lennox only finds it once a big gust of wind swings aside some loose ivy trails and she sees the round knob of a door.

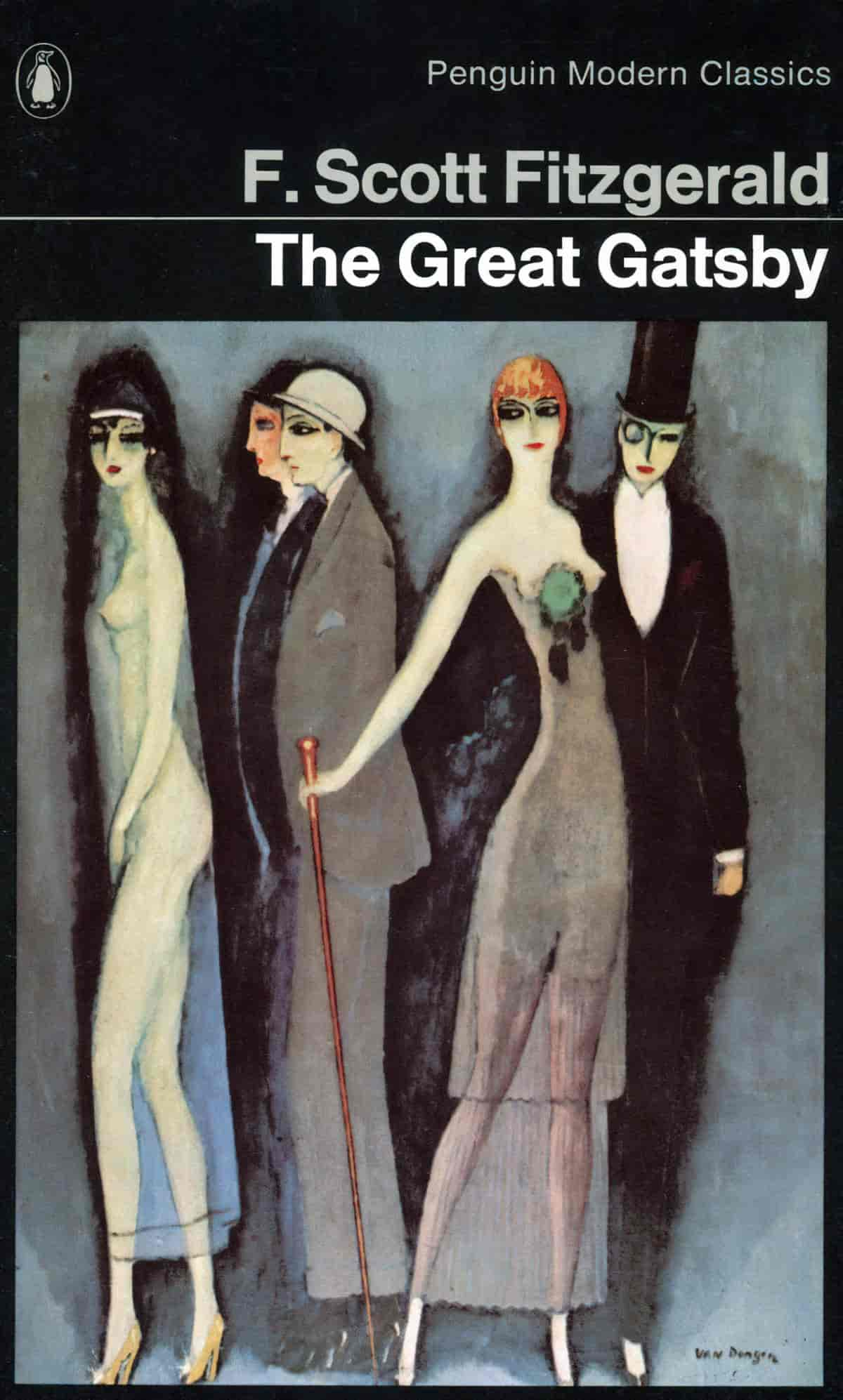

Veils In Gothic Literature

Gothic is not an easy thing define and I’ve even heard writers say it’s such a broadly used term it’s useless. For creators, it certainly is. But academics keep trying to define it, and I do my best to outline dominant understandings of ‘Gothic’ as it applies to literature here.

The Gothic form is easy to laugh at because it has a surface to it which is full of hackneyed, over-the-top symbols: haunted houses, bats in the belfry, virginal maidens (often subverted).

Veils are a fairly common feature of Gothic stories. For more on this, check out the work of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, who basically says that it’s easy to get caught up on the surface ‘clap-trap’ of Gothic, but Gothic stories have many interesting layers.

The veil, in her analysis, is not simply a concealment and inhibition of sexuality, it comes, by a process of metonymy, to represent the thing covered and is then ‘a metaphor for the system of prohibitions by which sexual desire is enhanced and specified’.

from the introduction to Modern Gothic: A Reader edited by Sage and Lloyd Smith

Veils Around The World

The veil is thought to protect (as an apotropaic item of clothing). Therefore, somehow penetrating or lifting a veil happens in many kinds of initiation around the world and across history, not just in marriage.

In Islam, the Qu’ran says women should be addressed from behind a veil, hence the existence of the hijab, which is how the symbolism has been put into practice. Because veils are seen as bi-directional, defenders of the hijab say that it offers women freedom (from objectification) as well as protection.

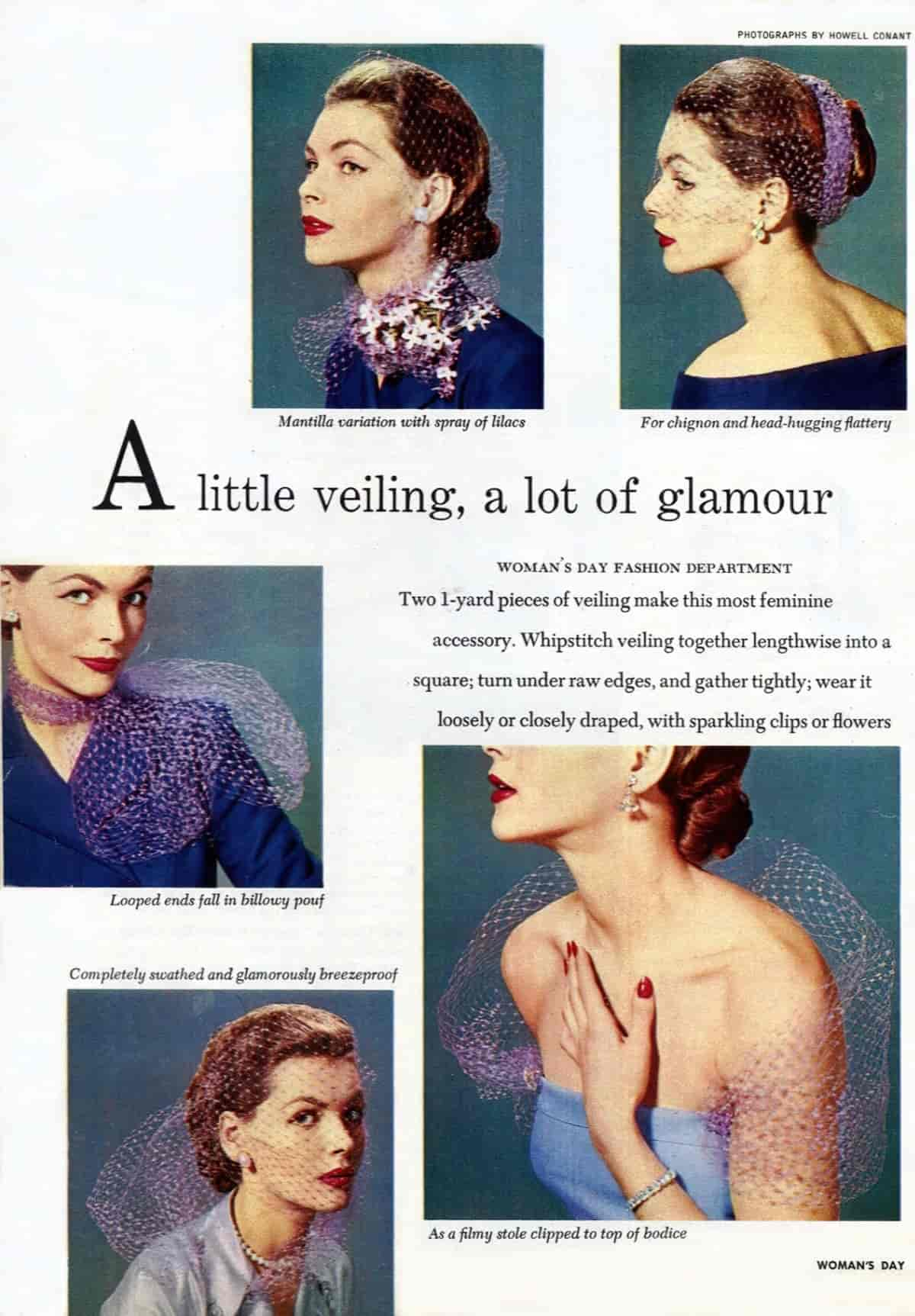

Brides often wear veils, and perhaps again once widowed. The veil is a crucial part of the attire of the 19th century Black Widow. Ironically, these veils afforded the opposite of ‘protection’ — they were actively harmful to health:

Called a “weeping veil,” this shroud was made of a crimped silk fabric called crape, and wearing it allowed one to “weep with propriety,” as the women’s magazine M’me Demorest’s Quarterly Mirror of Fashions put it in 1862. Unfortunately, due to the dyes and chemicals used to the process the fabric, these veils could also cause skin irritation, respiratory illness, blindness, and even death.

Racked

When did Western women give up the tradition of wearing a mourning veil?

…by the 1890s, mourning conventions had shifted. Many fashion magazines and etiquette manuals were now urging readers to wear just a light net veil, or stick with the crape veil but let it hang down one’s back. Sales of mourning crape plummeted.

Racked

We still see the custom of mourning veils. In Muslim tradition, woman mourners are asked to wear a scarf or veil to funerals.

In Buddhism, the concept of Maya (translated as “pretense” or “deceit”) functions as a symbolic veil which separates pure reality from the illusory nature of the world we live in. I suspect the symbolism of the mask also comes into play here and is equally bi-directional — the separation clearly works both ways.

The following is from an anthropologist studying the Pentecostal and supernatural beliefs in Papua New Guinea. Importantly, many people in this part of the world mix supernatural beliefs with beliefs introduced by Christianity, hence talk of witches:

First, Christian piety manifests as “light” or “shine” in the body and person of the devout. Pious Christians, those who especially exhibit the presence of the Holy Spirit, are so bright they are like “mirrors”: they reflect back the invasive gaze of the witch. Second, and similarly, people discuss the blood of Christ as offering protection from witches. While often used as a metaphor, where the blood of Christ symbolizes redemption from sin, it is often described by my informants in quite material and bodily terms as a veiling shroud that prevents witches from seeing inside a person. Rather than the interior of bodies, the witches will instead see only the blood of Christ. One might say that the blood of Christ on the exterior of the body is actually the interior of the Christian body being made exterior, a body being turned inside-out. All of these ideas evoke powerful Melanesian constructs linking power and persuasion to what can and cannot be seen, how people make themselves visible to one another, and how that visibility implicates people in moral relationships to each other.

Becoming Witches

In other words, symbolic veils help to make someone immune from the powers of persuasion, whether that persuasion comes from witches, or capitalism, or wherever. When I think of a veil, I conjure the image of a wedding veil, made of diaphanous material. But in this part of the world, the Blood of Christ functions as a veil.

Therefore, when considering the concept of a veil, the Papua New Guinean example reminds us that veils come in various forms, in their case, the blood of Christ. As a Westerner, I personally find this idea of blood as veil a difficult concept.

This difficulty demonstrates how significantly our own cultures mould us when it comes to the ‘universal’ interpretation of symbols (not so universal after all).

The Hag of Beara

The Hag of Beara (Irish: An Chailleach Bhéara, also known as The White Nun of Beara, or The Old Woman of Dingle) is a mythic Irish Goddess (a Cailleach or a divine hag, crone, or creator deity; literally “veiled one” (caille translates as “hood”, the implications that the woman is a nun) associated with the Beara Peninsula in County Cork, Ireland, who was thought to bring winter. She is best known as the narrator of the medieval Irish poem “The Lament of the Hag of Beara”, in which she bitterly laments the passing of her youth and her decrepit old age.

Wikipedia

Cailleach means three things in Gaelic, unrelated until you know the mythology:

- Hag

- Nun

- Veil

Like many violent, ugly, cannibalistic hags from folklore, the Hag of Beara is unhappy because she hasn’t had any children. She must also live forever because she doesn’t have children to carry on the family line.

Why the veil, given what we know about how veils function symbolically? It’s popularly believed that she wore a veil to make herself mysterious. But does that go far enough?

The guy in the video below uses the analogy used by Joseph Campbell, the snake shedding its skin. One standout feature of this particular Irish hag is that if a man dares to kiss her, he experiences the privilege of a rebirth. So the veil in relation to this particular hag might emphasise the fact that there is a barrier between two quite different states of being.

Veils and Katherine Mansfield

“Taking The Veil” is a short story by Katherine Mansfield, about a young woman who imagines a life in which she is about to become a Bride of Christ instead of a flesh-and-blood earthly bride. Many of Mansfield’s short stories lamented the disappearance of freedom and autonomy which came with subsuming oneself inside a relationship, especially as experienced by women. For me, the veil in this story exists symbolically as a division between the main character’s fantasy life and her real one.

Mansfield was no doubt interested in the symbolism that could be eked out of a veil. In “A Dill Pickle“, about a woman who meets an old beau and finds him even more insufferable than he was six years ago, Mansfield concludes with:

She had buttoned her collar again and drawn down her veil.

This is an excellent example of multivalent veil symbolism. Sure, Vera is closing herself off to the possibility of marriage with this man. But I think there’s more going on. Throughout their meeting in the café, Vera has been careful to subdue her appetite. She hesitates before accepting sustenance, as expected of a lady. But this is a thin disguise. The ‘beast’ in Vera is clawing to get out. In the end, she must leave the café before it reveals itself, busting her cover as a society lady, living covertly in genteel poverty. The ‘thinness’ of the veil is what’s emphasised here.

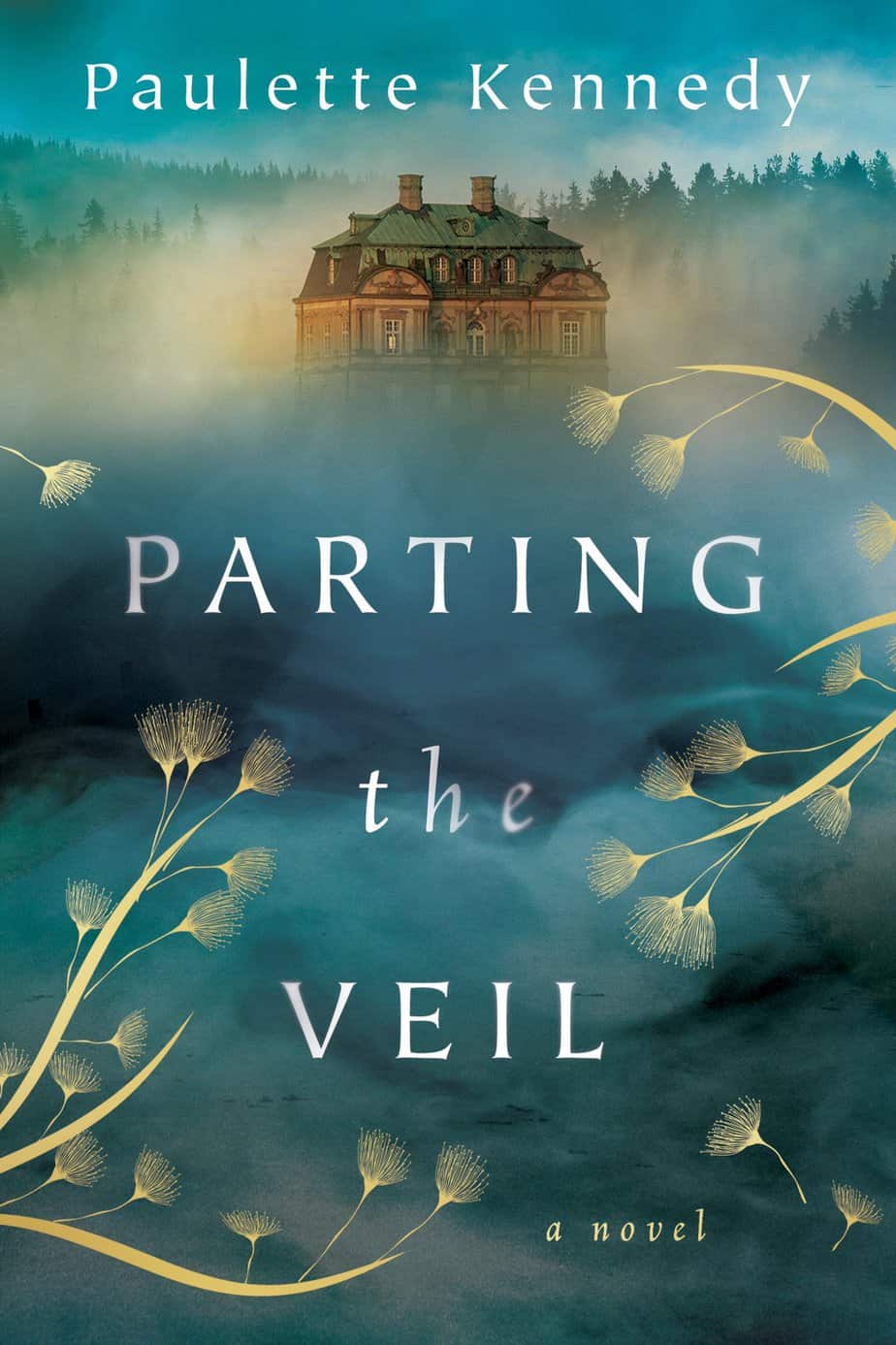

When Eliza Sullivan inherits an estate from a recently deceased aunt, she leaves behind a grievous and guilt-ridden past in New Orleans for rural England and a fresh start. Eliza arrives at her new home and finds herself falling for the mysterious lord of Havenwood, Malcolm Winfield. Despite the sinister rumors that surround him, Eliza is drawn to his melancholy charm and his crumbling, once-beautiful mansion. With enough love, she thinks, both man and manor could be repaired.

Not long into their marriage, Eliza fears that she should have listened to the locals. There’s something terribly wrong at Havenwood Manor: Forbidden rooms. Ghostly whispers in the shadows. Strangely guarded servants. And Malcolm’s threatening moods, as changeable as night and day.

As Eliza delves deeper into Malcolm’s troubling history, the dark secrets she unearths gain a frightening power. Has she married a man or a monster? For Eliza, uncovering the truth will either save her or destroy her.

Header image: The Entombment c. 1805 William Blake 1757-1827