Where there is a river there is symbolism. At least, in stories. The nature of rivers also differs between cultures.

A good example of that is between the ‘masculinist engineering world view’ and the Native Himalayan world view. The difference has very real consequences:

In the masculinist engineering world view, rivers are lifeless entities, composed only of water. They can be plumbed, split, or made to walk in a straight line. Rivers are valued for their water, but not for the vibrant matter and life that they also carry. Himalayan rivers used to bring fine silt to north Bihar from Nepal which would be deposited across the plains, making it one of the most fertile agricultural regions in the subcontinent. Embankments cut off this efficient transport of nutrients, making the land poorer and agribusiness corporations richer. It has been calculated that each year the Kosi carries 19 cubic metres of sediment per hectare, five times higher than any other river in Bihar. Unable to deposit this sediment, the Kosi is forced to retain it. This raises its bed, making floods an inevitability, not an accident.

Amitangshu Acharya

RIVERS AND SUPERNATURAL CREATURES

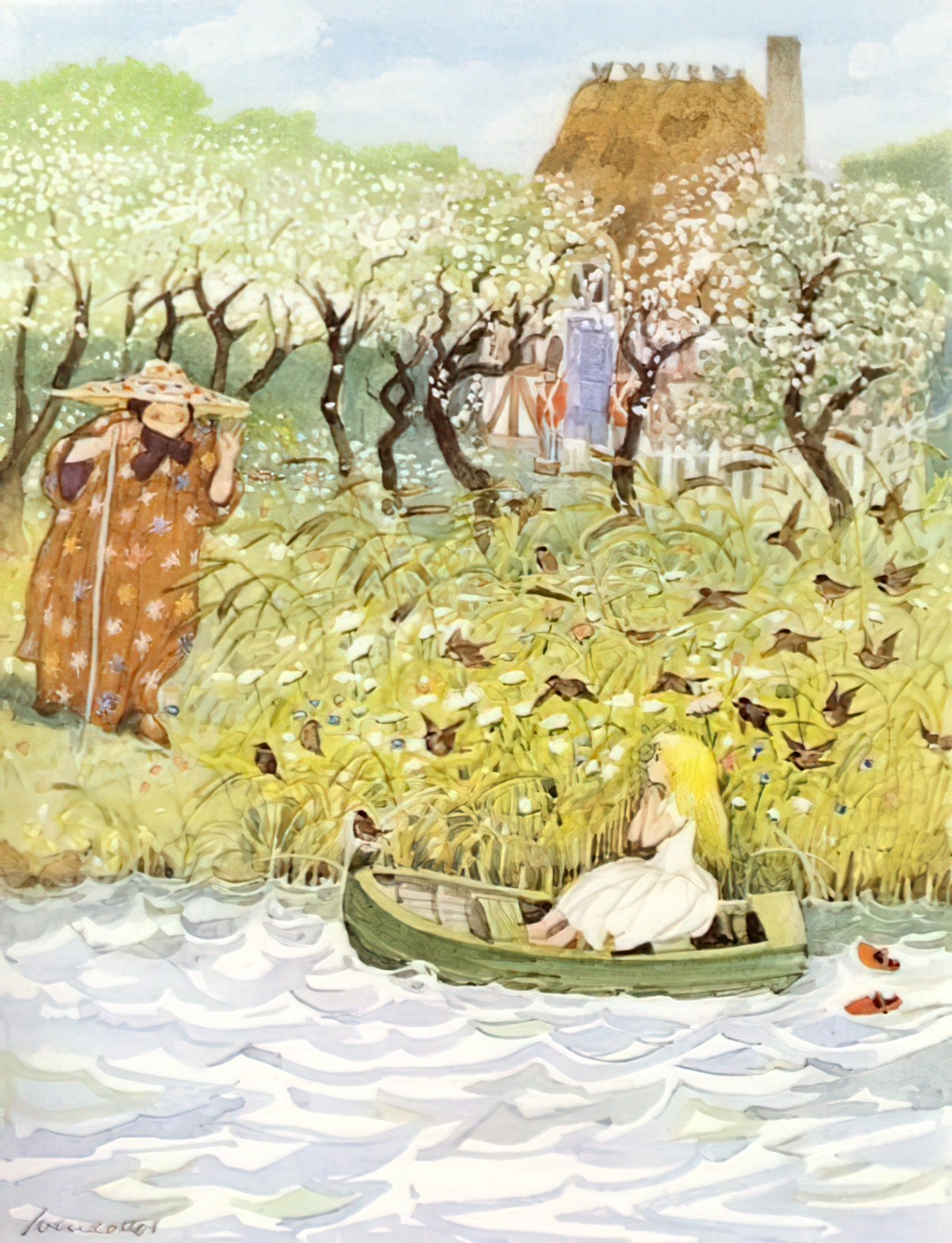

NYMPHS

In Greek mythology you often find nymphs near rivers. Nymphs love sitting by water (especially the river Ilissos). They also love shade, and trees grow tall and healthy when they have a good source of water; hence riverbanks are beautifully shady places.

Water is central to children’s and young adult literature as motif and metaphor: In Pam Muñoz Ryan’s Esperanza Rising, two characters are in a relationship described as being separated by a wide, difficult-to-cross river; in The Lorax Dr. Seuss warns us to protect our environment by planting a truffula tree seed and enjoins us to “Give it clean water. And feed it clean air”; and the poetry of Langston Hughes uses water in its various forms to compare the complexities of race to a deep river, to characterize a lost dream as a “barren field frozen with snow,” and to call on us all to re-imagine and reclaim the American dream, saying that “We, the people, must redeem/ The land, the mines, the plants, the rivers.”

SDSU Children’s Literature

THE BUNYIP

The Bunyip is an Australian cryptid who can be found on riverbeds. For more on the Bunyip, listen to this podcast.

River As Liminal Space

What does ‘liminal’ mean, anyway?

Rivers mark boundaries and are in between spaces, symbolically similar to crossroads, train stations, wall cavities and so on. It follows that riversides are spiritually rich spaces as well, a good place to grieve, to commune with your god, or to meet fairies and goddesses.

River As Power Of Nature

The flow of a river is a force outside human control (at least, before the days of civil engineering). Crossing a river is unexpectedly treacherous. It’s a common way for trampers (hikers) to die in my home country of New Zealand. Rivers rise suddenly and without warning. In early modern England, it was more common than you might imagine to die while collecting water. After childbirth, alongside burning to death in a fire, falling into a body of water (including wells) was a peril for women in particular. When I researched my own family tree, I discovered a great, great uncle had died young while trying to cross a river with horses. Perhaps you’d find similar. Sure as eggs, at least someone adjacent to your ancestry line has come to grief in a river.

Like the opponents of cosmic horror, the river is ancient and when something predates humanity, this confers inherent horror for us. We know it was here before we were, and can deduce it’ll still be here long after we’re gone.

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins

Langston Hughes, poet

My soul has grown deep like the rivers

Roald Dahl created Wonka’s factory as a symbolic forest. Sitting mysteriously just outside Charlie’s town, nobody is able to enter this forest and get past the mighty beast. This metaphorical forest, we discover, is full of all the perils of a fairytale forest — poisonous berries, tests to see if you’re good or bad, dangerous creatures and a treacherous (chocolate) river. Note the juxtaposition: Something so sweet but so dangerous.

Augustus Gloop is at the mercy of his own natural greed and is killed by the river.

Willy Wonka’s river reminds me of the famous river of flowers in the Netherlands.

More happily, perhaps, an opponent can be defeated by throwing him/her into the river.

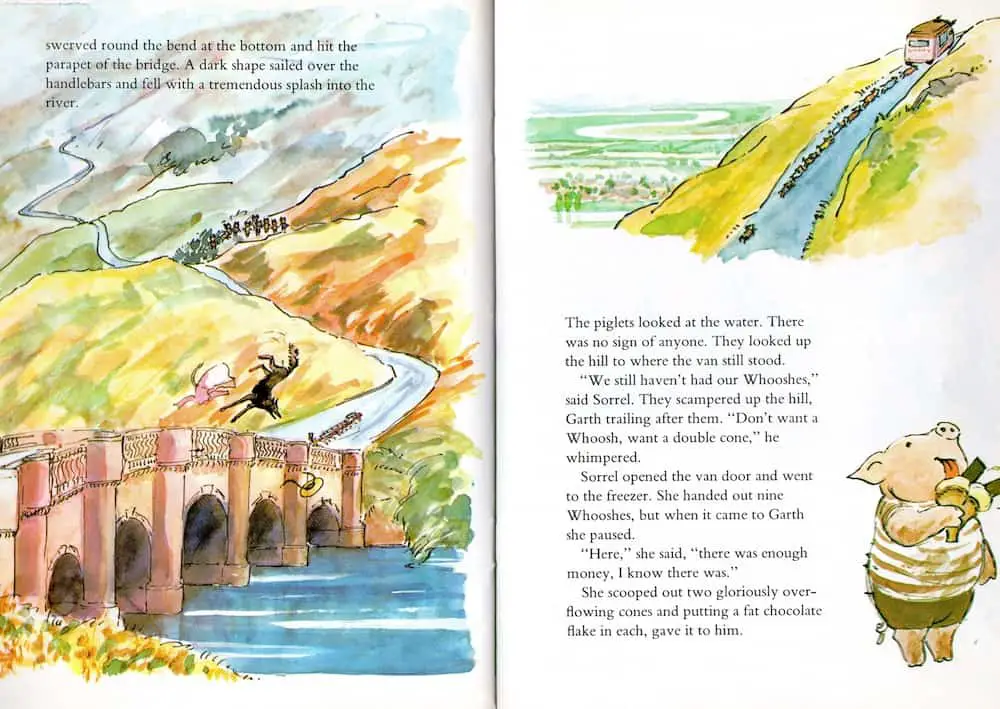

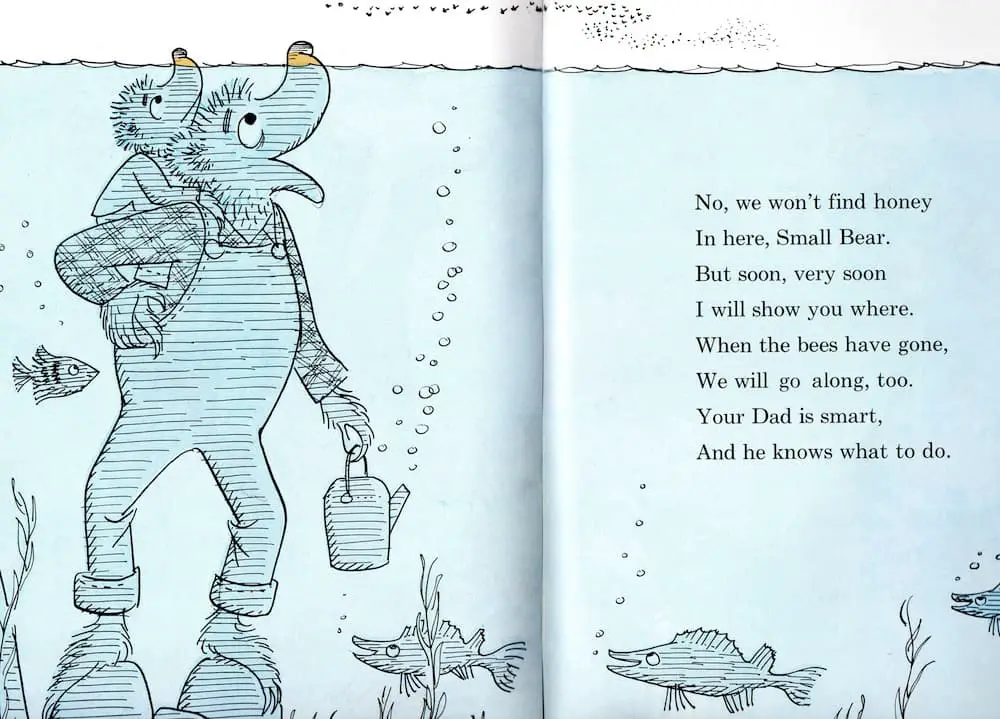

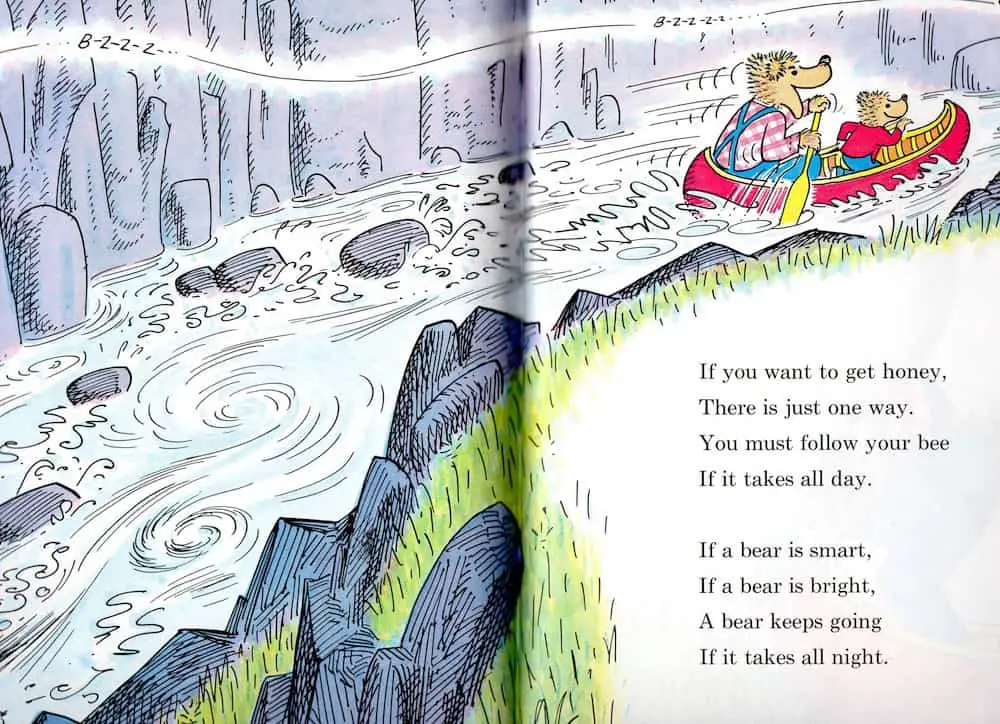

In a comedic journey, the danger of a river can be inverted. In The Big Honey Hunt a father and son hide in safety from a swarm of angry bees whose honey they are trying to plunder. In this case, the loveable main characters are saved by the river.

River As Symbol Of Fertility

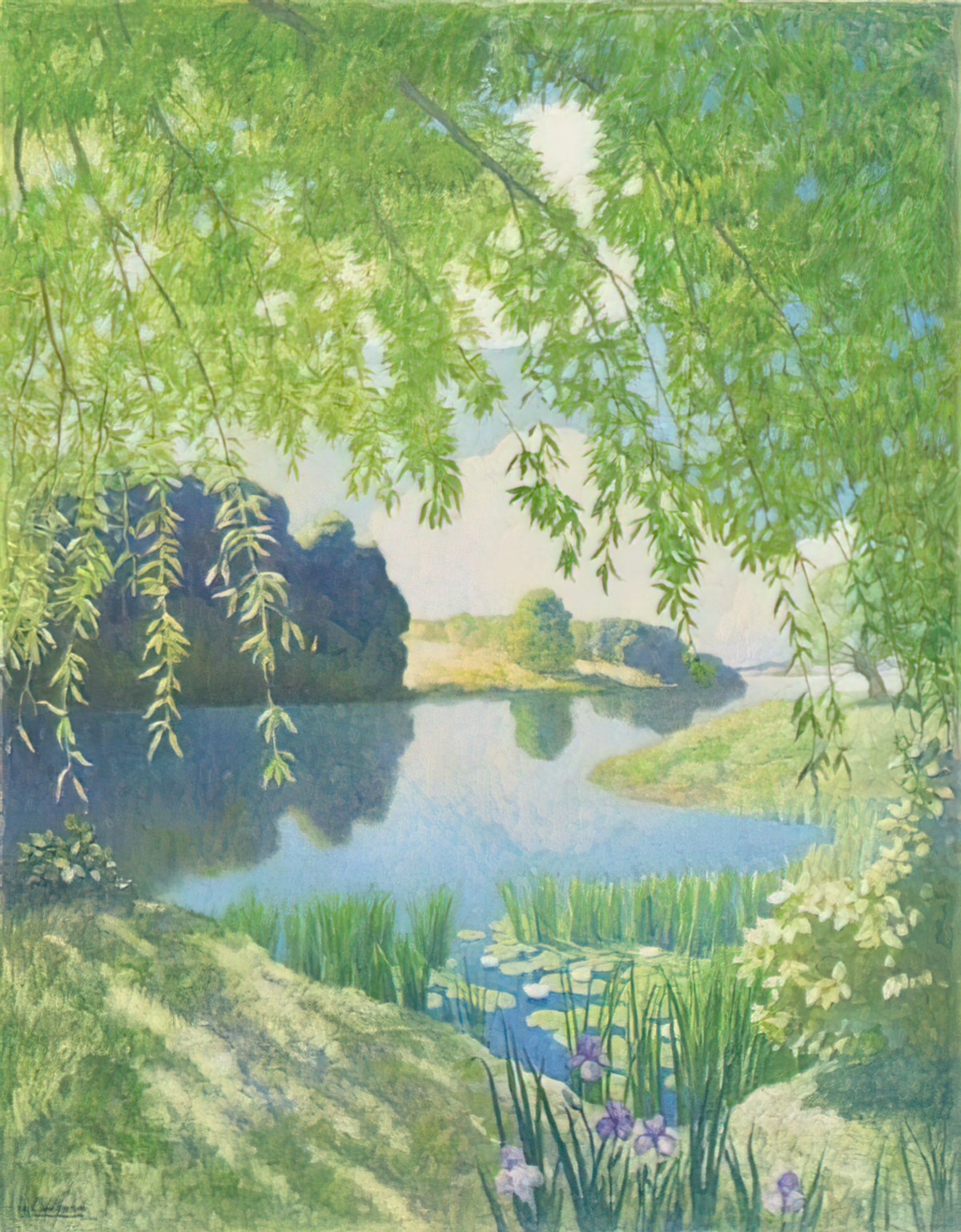

The riverside is often depicted as a feminine space.

the Yangtze, like most rivers, is associated with the feminine. To my mind, this is not only mythopoetic; it is also logical. After all, rivers help us grow the food we need to nourish ourselves. All over the world, women too have primary responsibility for feeding. […] Both women and rivers enable life but have little influence at decision-making level. The silencing of women and rivers in institutions of power bridges a connection between reality and myth; it is no wonder river goddesses are vengeful.

Minna Salami

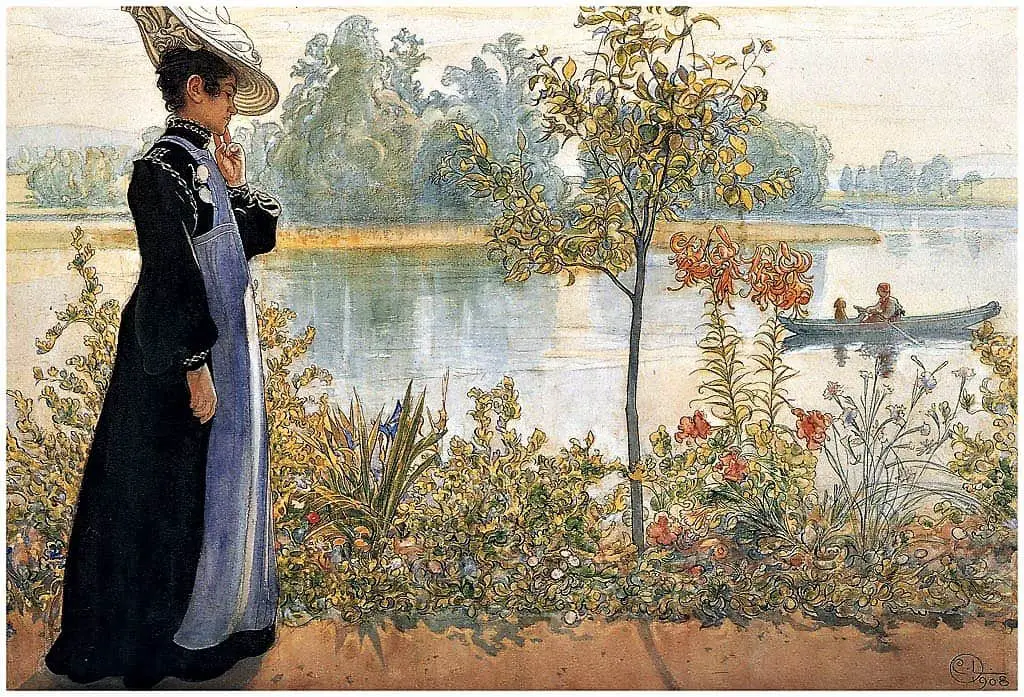

In ‘hygge‘ picture books there will probably be a gentle river nearby.

[Mole] thought his happiness was complete when, as he meandered aimlessly along, suddenly he stood by the edge of a full-fed river. Never in his life had he seen a river before — this sleek, sinuous, full-bodied animal, chasing and chuckling, gripping things with a gurgle and leaving them with a laugh, to fling hitself on fresh playmates that shook themselves free, and were caught and held again. All was a-shake and a-shiver — glints and gleams and sparkels, rustle and swirl, chatter and bubble. The Mole was bewitched, entranced, fascianted. By the side of the river he trotted as one trots, when very small, by the side of a man who holds one spell-bound by exciting stories; and when tired at last, he sat on the bank, while the river still chattered on to him, a babbling procession of the best stories in the world, sent from the heart of the earth to be told at last to the insatiable sea.

Kenneth Grahame, The Wind In The Willows

Sometimes the river is so… nearby… it passes through the dwelling.

Below we have an Australian picnic scene. Even in the dry landscape of Australia, a river is necessary for a truly cosy outdoors experience.

The river is an essential element in what humans consider beautiful. As art philosopher Denis Dutton wrote, ‘beauty is in the culturally conditioned eye of the beholder’.

Beauty comes in many forms, depending on your cultural conditioning. But there is another, deeper, widely shared part of humanity in which we widely agree — at a very deep level — on what makes a beautiful environment. No surprise: it includes a body of water. Water is so important to life that the nearby presence of water is soothing and reassuring — and indeed necessary — to us. You’ll find discussion of this at the 7:10 mark in the TED talk below.

(If you were wondering what else makes for a beautiful landscape: a tree on a savannah that forks near the ground — so that we can easily scramble up it — and a path that meanders into the distance towards some kind of shoreline.)

River As Metaphor For Time

Time is nothing like a river. (It’s nothing like a train, either.) No one fully understands how time works, but astrophysicists tell us it is nothing like a ladder, road, tide or thread. All of these things and more have been used in stories as a metaphor for time, because that is how we perceive it. We humble, Earth-bound humans can manage a few different but related metaphors: Are we bystanders on the edge of the river, watching time go past, or are we bobbing in the water? That’s another question, dealt with differently by different authors.

Back to the example above. There comes a moment in every comedic adventure when the picture book writer must indicate that a whole heap of other things happened/a whole heap of time passed and EVENTUALLY… Here we have another scene from The Big Honey Hunt by Stanley and Janice Berenstain in which father and son have embarked on their fruitless honey-collecting mission. The river symbolises time, as reinforced by the text.

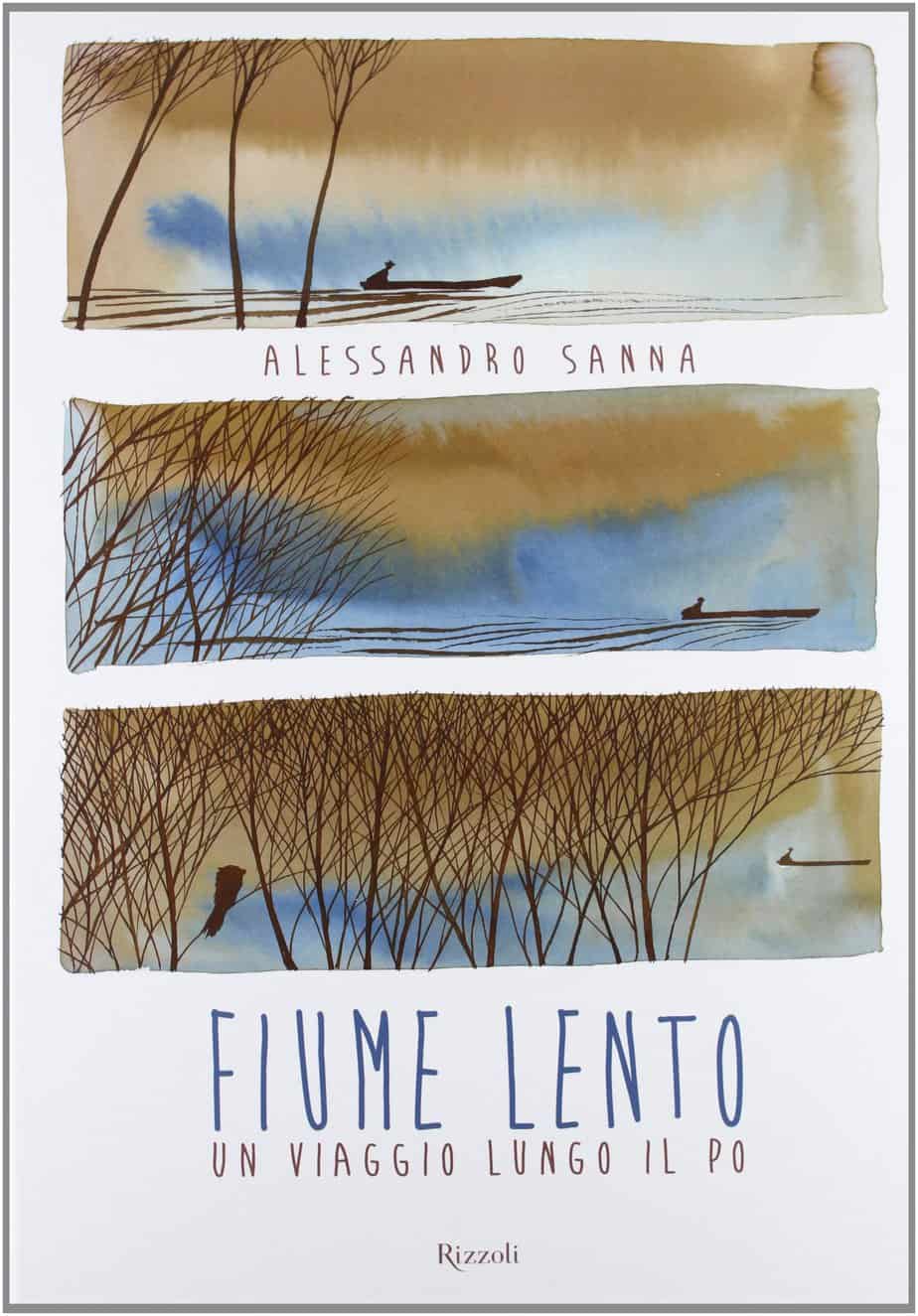

Italian picture book Fiume lento (Slow River) by Alessandro Sanna marries the symbolism of the river with the symbolism of seasons in a fascinating multivalent metaphor:

A wordless picture book that crosses over the age range, the story is told through the pictures. Life along the Italian river Po is described in four episodes, one for each season of the year: the tragedy of the flood during autumn; in winter time the night birth of a calf in a warm stable; in springtime the village celebration for the rebirth of nature, and the magic beginning of a love story; and finally, in summer, the escape of a tiger from a circus and its unbelievable meeting with a painter, in a sort of magic moment out of time. Through the use of pictures the book allows everyone to discover their own words and emotions, celebrating with poetry the flowing of the Po river and recalling the cycle of nature and rural life, in its alternating of night and day, of death and life.

The World Through Picture Books

River As Symbol Of Inevitability and Fate

Related to the concept of time is ‘inevitability’. Annie Proulx opens her short story “On The Antler” by describing an old man nearing the end of his life. As a young man he never liked to read:

But in the insomnia of old age he read half the night, the patinated words gliding under his eyes like a river coursing over polished stones: books on wild geese…

“On The Antler” by Annie Proulx

A river picks its path and there’s nothing individuals can do to stop it from running its course. This theme is expanded upon over the rest of the story. A few years ago my hometown of Christchurch suffered a series of hugely damaging earthquakes. Two houses, side-by-side: One totally ruined, the other with barely any damage at all. My cousin used that phrase to describe the phenomenon, and how her neighbour’s house was ruined while she only lost her hot water cylinder to damage: ‘It picks its path’. Earthquakes, like rivers, lend themselves to personification.

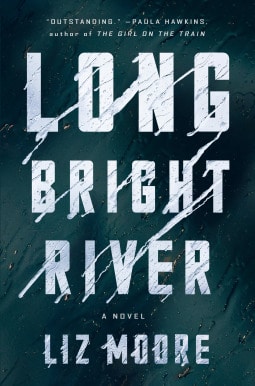

Two sisters travel the same streets, though their lives couldn’t be more different. Then, one of them goes missing.

In a Philadelphia neighborhood rocked by the opioid crisis, two once-inseparable sisters find themselves at odds. One, Kacey, lives on the streets in the vise of addiction. The other, Mickey, walks those same blocks on her police beat. They don’t speak anymore, but Mickey never stops worrying about her sibling.

Then Kacey disappears, suddenly, at the same time that a mysterious string of murders begins in Mickey’s district, and Mickey becomes dangerously obsessed with finding the culprit–and her sister–before it’s too late.

Alternating its present-day mystery with the story of the sisters’ childhood and adolescence, Long Bright River is at once heart-pounding and heart-wrenching: a gripping suspense novel that is also a moving story of sisters, addiction, and the formidable ties that persist between place, family, and fate.

River as Lullaby

Sometimes the process of falling asleep is conceptualised as a river.

River As Life From Birth To Death

In literature as in life, cities and towns often spring up on riverbanks, seemingly brought to life by the river’s movement. The source of the river, typically small mountain streams, depicts the beginnings of life and its meeting with the ocean symbolises the end of life. The river is one of my favourite metaphors, the symbol of the great flow of Life itself. The river begins at Source, and returns to Source, unerringly. This happens every single time, without exception. We are no different.

Jeffrey R. Anderson, from The Nature of Things: Navigating Everyday Life with Grace (Balboa Press, 2012)

Fear – Khalil Gibran

It is said that before entering the sea a river trembles with fear. She looks back at the path she has traveled, from the peaks of the mountains, the long winding road crossing forests and villages. And in front of her, she sees an ocean so vast, that to enter there seems nothing more than to disappear forever But there is no other way. The river can not go back. Nobody can go back. To go back is impossible in existence. The river needs to take the risk of entering the ocean because only then will fear disappear, because that’s where the river will know it’s not about disappearing into the ocean, but of becoming the ocean. Khalil Gibran

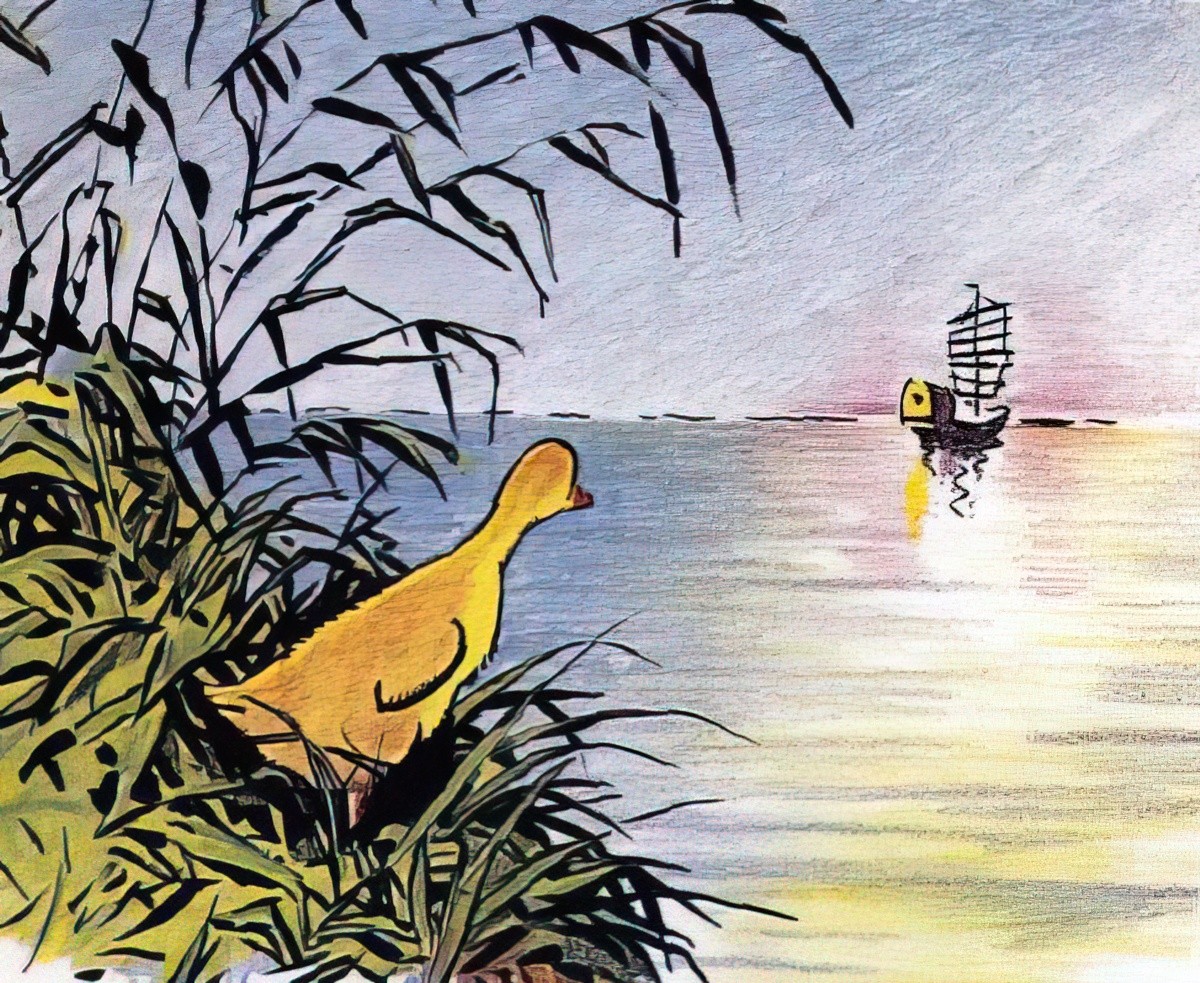

In The Story About Ping the river has various meanings but most of all this is the story of one duck’s mythic journey towards death and back again. The river as character arc.

There were two places my father had told us to fear. One was the river, which sometimes raged after a heavy rain and was, at all times, apt to drown things. The other was the part of the mountain above where the families lived. “Bears,” he often said. “And coyotes. And steep rock faces. And ledges that drop off into nothing. So don’t wander up too far, you hear me?”

Echo Mountain, Lauren Wolk (2020)

River As Unstoppable Force

This metaphor can symbolise something untamed, beastlike and scary, or it can be reframed as cooperation, and banding together for the greater good.

All rivers start as tiny streams at mountaintops. As the streams trickle down, they are met by other small streams and tributaries, together growing larger and larger until their mutual flow becomes a river. The more the river widens, the more power it has to circumvent the barriers in its way. When a river meets an obstruction, it moves under, above, around, or through whatever prevents it from flowing. When blocked, a river revolts with all its weight, including that of the streams and tributaries that pour into it, until it flows smoothly again. Rivers flow down mountains, valleys, and plateaus. They flow into lakes, ponds, and seas. At times the process is barely visible, like the gentle, lapping flow of a river surface while deep at the river’s bottom mighty streams surge. At other times a river’s explosive movement is visible, for instance, when a dam can no longer withstand the force of water dashing against it and blazes open to a furious whorl of water. With the help of gravity, rivers swirl, surge, and push toward their final destination, the ocean.

Minna Salami

Rivers have been given room to flood safely in the Netherlands for two decades, mitigating against flooding during severe weather events. Forest and Bird freshwater advocate Tom Kay talks to communities and local government groups keen to hear how accommodating a river prone to flood (rather than hem it in with engineering) can help manage flood risk for communities, and preserve ecosystems.

Tom Kay: let the river go with the flow

River As Boundary

The river is a sign of boundaries.

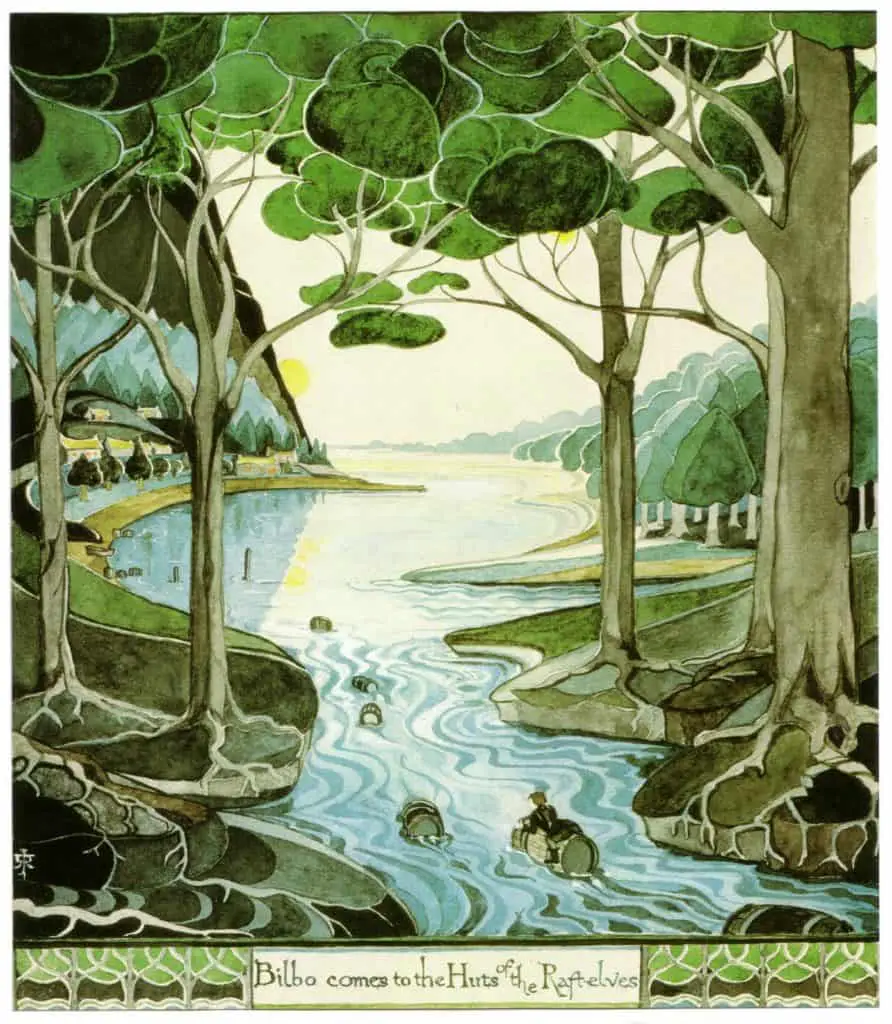

My analysis of The River Between Us by Richard Peck

(Roads snaking through a landscape work in the same way.)

As a boundary, the river is sometimes used to show the difference between civilisation and those outside it. In fairy tales, the forest is used in a similar way. In medieval Europe, outlaws really were banished to the parts where ‘civil’ people did not venture. There needed to be some sort of geographical marker to delineate law from outlaw — rivers and edges of forests were good for that.

The river has also been used as a symbolic passageway into the heart of the jungle and as a descent into the primitive nature of humanity. (Especially The Amazon and The Congo.)

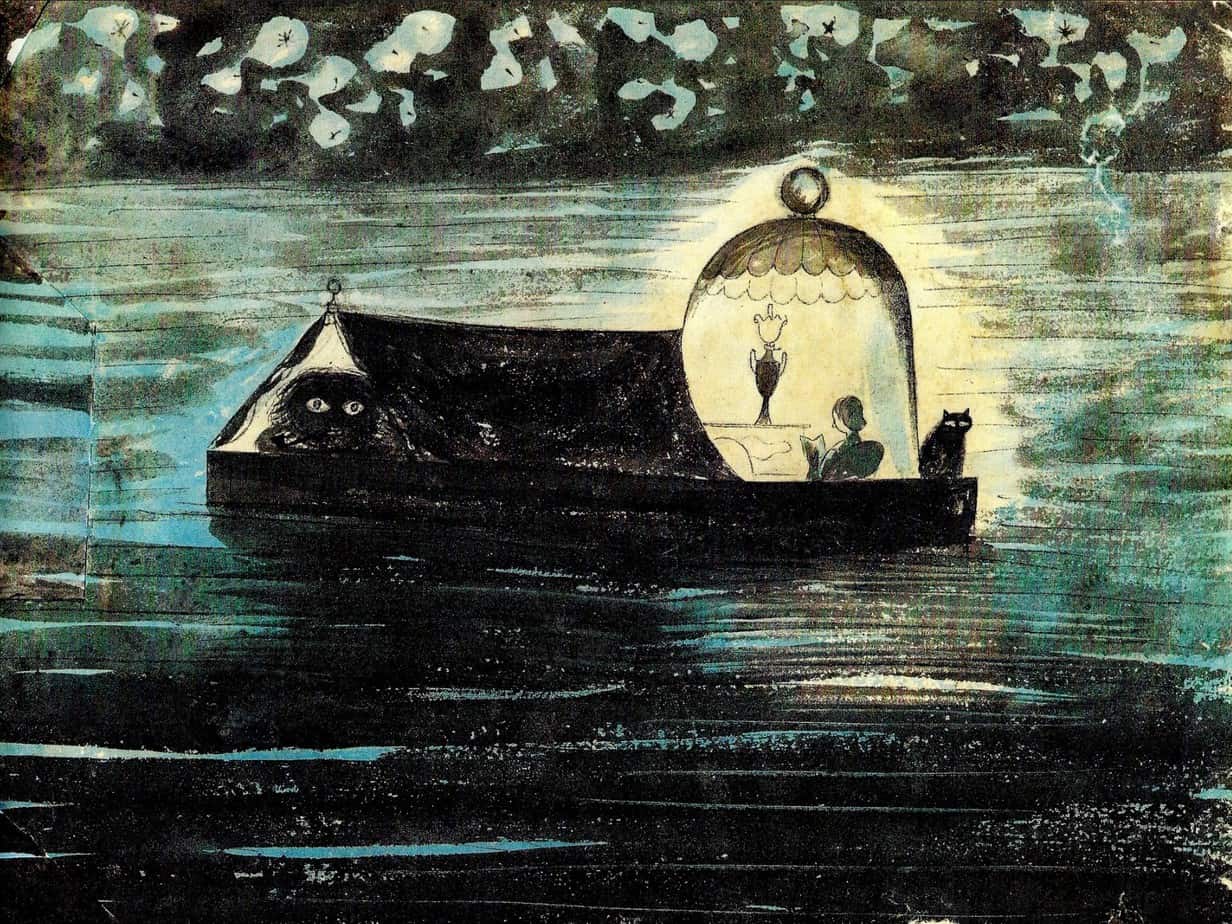

River as Death

Death is another kind of boundary — that between life and death. According to Greek mythology, The River Styx is a principal river in the Greek underworld (also called Hades). The river forms a border between the underworld and the world of the living.

Is there a real River Styx? In Italy there’s a river which runs partly underground, (the Alpheus River). This is viewed as a portal to the underworld where mortals can enter.

Any nightmarish story set on a river calls to mind the River Styx.

In the 1970s, a younger cadre of filmmakers and audiences saw the enemy sitting in seats of power. Underworld quests found more subversive avenues for expression, like Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), which conveyed the horrors of the Vietnam war through a nightmarish journey up the river Styx.

Paul Salmond

The Styx isn’t the only river to function in this way. Japanese culture as The Sanzu, Norse cultures have The Gjöll and so on.

The River Styx also isn’t the only River in the Realm of Hades. There are five rivers down there, apparently:

- Acheron (sorrow or vice) — This is an actual river located in northwest Greece. The Ancient Greeks called it the ‘river of woe’. Homer and Virgil contributed to the mythology around it. Virgil called it the main river of Tartarus, which is where you go if you’ve been bad.

- Cocytus (lamentation) — In Inferno, the first cantica of Dante’s Divine Comedy, Cocytus is the ninth and lowest circle of The Underworld.

- Phlegethon (fire) — Plato describes it as “a stream of fire, which coils round the earth and flows into the depths of Tartarus” (where bad people are sent).

- Lethe (oblivion) — There’s a pool in this river and people go here to lose their entire memories. Ovid wrote that the river Lethe flowed through the cave of Hypnos, god of sleep, where its murmuring would induce drowsiness.

- Styx (hate) — A guy called Charon needs a coin before ferrying dead people across to the other side. This led to the custom of placing coins inside dead loved ones’ mouths. Paupers and people without loved ones obviously can’t pay this guy, so they get stuck on the banks.

River As Fractal Plot Shape

In her book Meander, Spiral, Explode, Jane Alison writes about plot shapes in narrative. (I’ve written a lot about that here.)

As an example of a Fractal Plot, Alison offers Crossing The River by Caryl Phillips (1993). Significantly, the shape of the plot itself is like a river with many tributaries. The story is ‘four discrete narratives, but with no one narrator binding them. Instead, the book is polyphonic, taking the points of view of four characters and delivering them in different styles: letters, diary entries, mixtures of third person and first. Yet the stories all grow from a single seed: an original form of “intercourse” between white and black.’ The story begins with an original sin (the “shameful exchange” between white and black). Each part of the book juxtapose against each other, ‘in concept rather than causality’. This is all spurred by what happens in the prologue (so don’t anyone be making any blanket rules about how prologues are useless).

This story is framed at the other end by an epilogue. The father speaks to his lost children in the language of fractals’ by talking about how they’re broken off limbs of a tree. Then he continues the fractal theme by talking about selling his children “where the tributary stumbles and swims out in all its directions to meet the sea”.

Main point being, in a fractal story (also known as branching, among other names), you may well find the river used symbolically, to underpin the narrative structure as well as the themes.

River Personified As Old Man

The Mole was bewitched, entranced, fascinated. By the side of the river he trotted as one trots, when very small, by the side of a man who holds one spellbound by exciting stories; and when tired at last, he sat on the bank, while the river still chattered on to him, a babbling procession of the best stories in the world, sent from the heart of the earth to be told at last to the insatiable sea.

The Wind In The Willows

It’s funny about paths and rivers, you see them go by, and suddenly you feel upset and want to be somewhere else – wherever the path or river is going, perhaps.

Tove Jansson

Rivers and Cardinal Direction

Across cultures, words for north, east, south and west come from a few main parts of language: The rising and setting of the sun is a big one. Wind is another.

In some Western Hemisphere languages (with the notable exception of Sedang in Vietnam), the flow of rivers has influenced words for directionality. So, instead of saying ‘north’, they might say up river, upstream, down river, downstream. This tends to happen when there’s a nearby river which plays a large part in a small community.

The River Nile in Egypt has had an especially large part to play in the Egyptians’ sense of direction. The word for ‘to go north’ also meant ‘to go upstream’, or against the current.

River as Living Body

LAYERING THE SYMBOLISM

And I’ll dance with you in Vienna,

Leonard Cohen

I’ll be wearing a river’s disguise.

The hyacinth wild on my shoulder

my mouth on the dew of your thighs.

And I’ll bury my soul in a scrapbook,

with the photographs there and the moss.

And I’ll yield to the flood of your beauty,

my cheap violin and my cross.

Leonard Cohen knew how to layer symbols, which is why his lyrics are considered poetry set to music.

What if words got stuck in the back of your mouth whenever you tried to speak? What if they never came out the way you wanted them to? Sometimes it takes a change of perspective to get the words flowing.

I wake up each morning with the sounds of words all around me.

And I can’t say them all . . .

When a boy who stutters feels isolated, alone, and incapable of communicating in the way he’d like, it takes a kindly father and a walk by the river to help him find his voice. Compassionate parents everywhere will instantly recognize a father’s ability to reconnect a child with the world around him.

FURTHER READING

River Cities, City Rivers (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2018)

Cities have been built alongside rivers throughout history. These rivers can shape a city’s success or cause its destruction. At the same time, city-building reshapes rivers and their landscapes. Cities have harnessed, modified, and engineered rivers, altering ecologies and creating new landscapes in the process of urbanization. Rivers are also shaped by the development of cities as urban landscapes, just as the cities are shaped by their relationship to the river. In the river city, the city river is a dynamic contributor to the urban landscape with its flow of urban economies, geographies, and cultures. Yet we have rarely given these urban landscapes their due.

interview at New Books Network