Be it woods or forest, when a character enters the trees in fiction, beware! We learned this from fairytales, but is fear of the forest innate, or is it taught, partly via fiction?

I went to the woods because I wanted to live deliberately, I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to put to rout all that was not life and not when I had come to die, discover that I had not lived.

Henry David Thoreau

Come back, come back, my childhood;

Letitia Elizabeth Landon

Thou art summon’d by a spell

From the green leaves of the wild wood,

From beside the charmed well!

For Red Riding Hood, the darling,—

The flower of fairy lore.

‘Woods’ and ‘forest’ may describe basically the same geographical feature, but in English these words carry different connotations. Woods are more likely cosy and protective, and I feel woods are smaller than a forest. If lost in the woods, you’re more likely to stumble across the edge of them, back to safety.

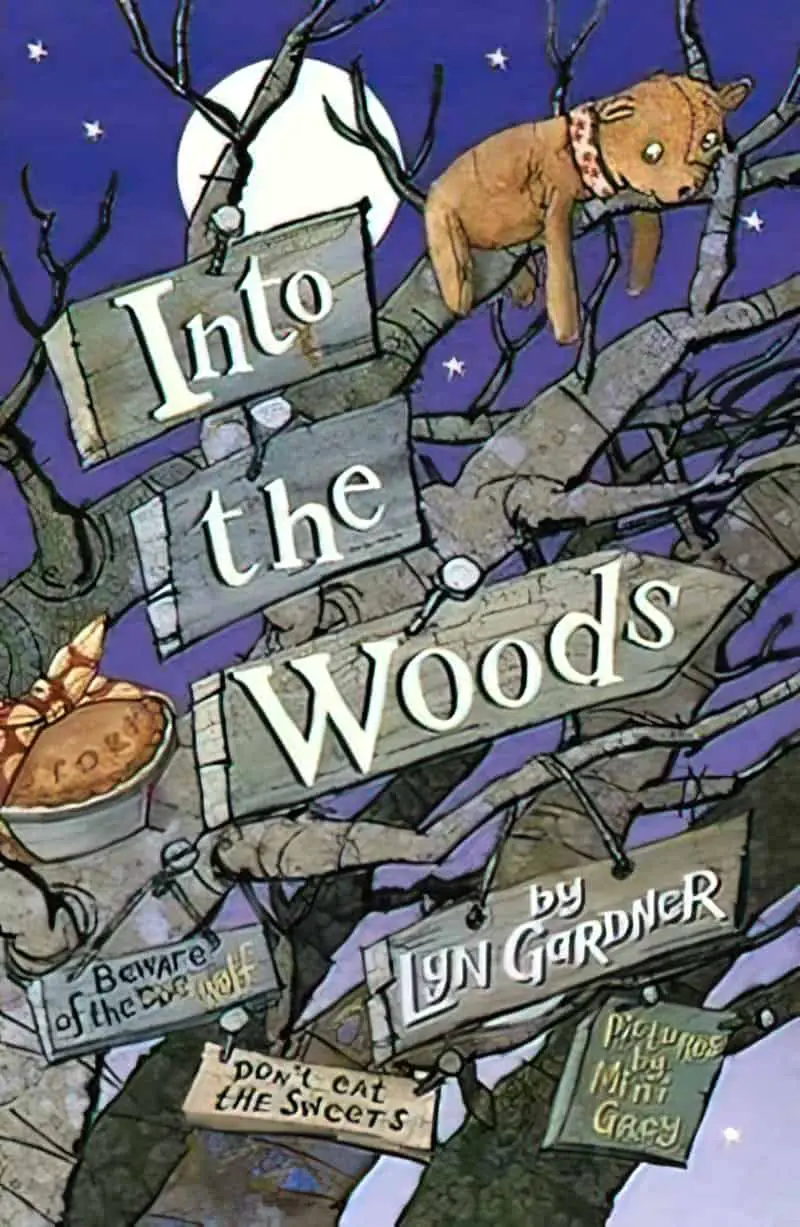

Into the Woods is a feminist fractured fairy tale comprising parts from various stories including “The Pied Piper“, “The Snow Queen“, “Hansel and Gretel” and “Little Red Riding Hood“.

That said, both forests and woods can be regarded as protective. In some stories, especially utopian ones, characters find all they need to survive among the trees — nuts and berries aplenty, appearing like manna, miraculously. Forests and woods function exactly how the storyteller needs them to function. When trees give us everything we need, this is the ultimate reminder that we have everything we need.

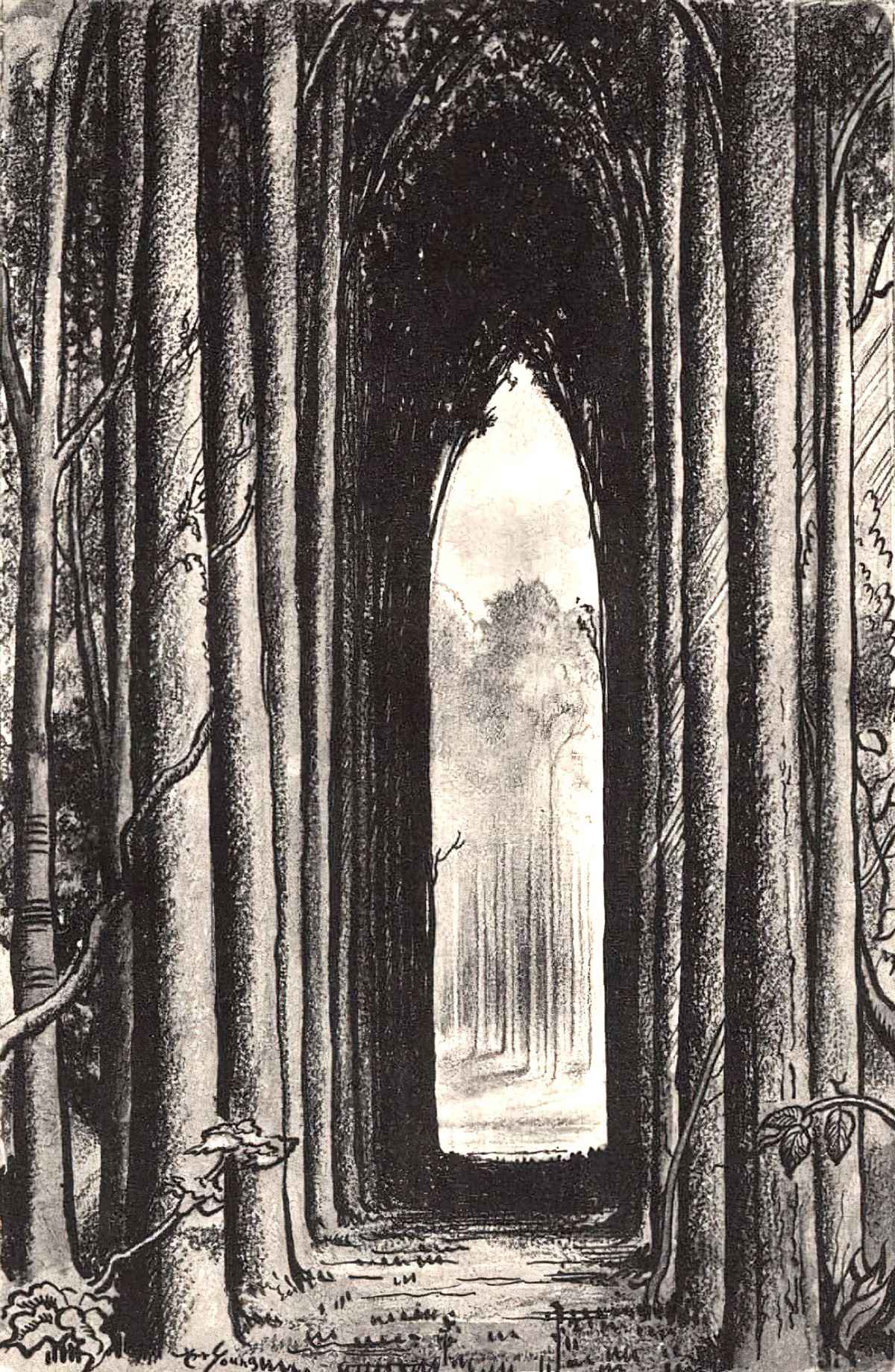

The central story quality of the forest is that it is a natural cathedral.

The tall trees, with their leaves hanging over us and protecting us, seem like the oldest wise men assuring us that whatever the circumstances, it will resolve as time moves on. It is the place where contemplative people go and to which lovers sneak away.

The journey into the wood is part of the journey into the psyche from birth through death to rebirth. Hansel and Gretel, the woodcutter’s children, are familiar with the wood’s verges but not its heart. Snow White is abandoned in the forest. What happens to us in the depths of the wood? Civilisation and its discontents give way to the irrational and half-seen. Back in the villages, with our sourced relationships, we are neurotic, but the wood releases our full-blown madness. Birds and animals talk to us, departed souls speak. The tiny rush-light of the cottages is only a fading memory. Lost in the extinguishing darkness, we cannot see our hand before our face. We lose all sense of our body’s boundaries. We melt into the trees, into the bark and the sap. From this green blood we draw new life, and are healed. […] All tales…are at some level a journey into the woods to find the missing part of us, to retrieve it and make ourselves whole. Storytelling is as simple — and complex — as that.

John Yorke, Into The Woods

The Worldwide Symbolism of the Forest

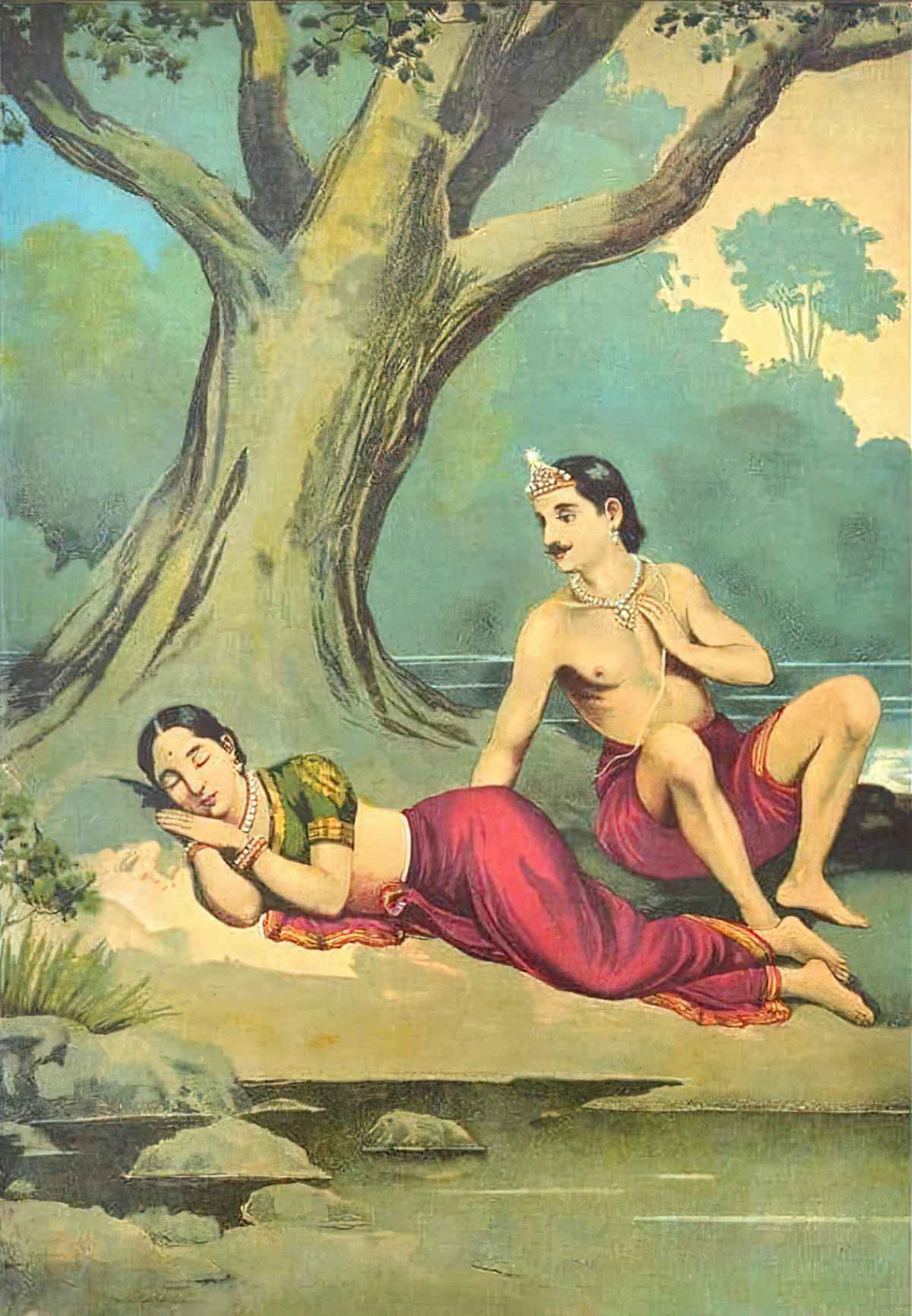

The picture below depicts a scene from Indian mythological tale of Nala and Damayanti. The story originally belongs to Indian epic Mahabharata. Forced to live in a jungle, while Damayanti was sleeping, Nala deserted her. (The full story is here.)

There’s nothing so bad as being lost in a forest.

The Forest In Early Roman Times

Early Romans had a particularly strong set of superstitions about these dense, trackless forests. For early civilisations, forests really were uncharted territory. Brigands and bandits could hide themselves in forests. Inside forests, it was everyone for themselves. Forests were also connected to religious belief. Many cultures had tree-worship as part of their customs e.g. Greece, Rome, Germany, a lot of other Indo-European cultures. Forests are important in Japan.

Even before fairytales there were many myths about forests. The story of Actaeon is one example. While out hunting, Actaeon came across Diana bathing naked. Diana immediately turned him into a deer and Actaeon’s own hounds tore him to bits.

The Forest In Medieval Times

These days, the forest can stand for a kind of Arcadia (utopia, heaven, idyll). But in Medieval England, the word ‘forest’ had a technical meaning and stood for something that was far from idyllic. Robin Hood and the Monk is the earliest of the Robin Hood stories. It opens by creating a picture of a forest idyll, but note that the word ‘forest’ is accompanied by ‘green wood’:

In summer, when the woods do shine,

And leaves be large and long,

It is full merry in fair forest

To hear the birdies song,

To see the deer draw to the dale,

And leave the hills so high,

And shelter in the leaves so green,

Under the green wood tree.

The concept of ‘green wood’ runs throughout the medieval outlaw stories, and when the forest is portrayed as a refuge, ‘green wood’ is preferred over ‘forest’. Green wood = modern day meaning of forest. Terry Jones explains what ‘forest’ meant in Norman England:

One of William’s first acts as conqueror of England was to create ‘The New Forest’. This didn’t mean he planted a lot of nice trees so people could enjoy a picnic in the shade. What he was doing was ear-marking a vast tract of land as his own personal hunting-ground. This is what the Norman word ‘forest’ meant. Whether there were trees or not wasn’t really the point. The ‘forest’ was wherever ‘Forest Law’ applied, and ‘Forest Law’ was not something anyone wanted to live under.

Towns and villages could be, and were, destroyed, and every animal and tree became royal property. The forest was administered by royal officials with draconian powers, who replaced the community as denouncers before the court.

Terry Jones, Medieval Lives

In other words, medieval forests became covered in trees because people were shooed off the land and were no longer able to civilise it.

Shakespeare

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, to take one example, the woods outside Athens are the realm of the fairies and spirits. Shakespeare was well-versed in Ovid, a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. Ovid is today best known for the Metamorphoses, a 15-book continuous mythological narrative.

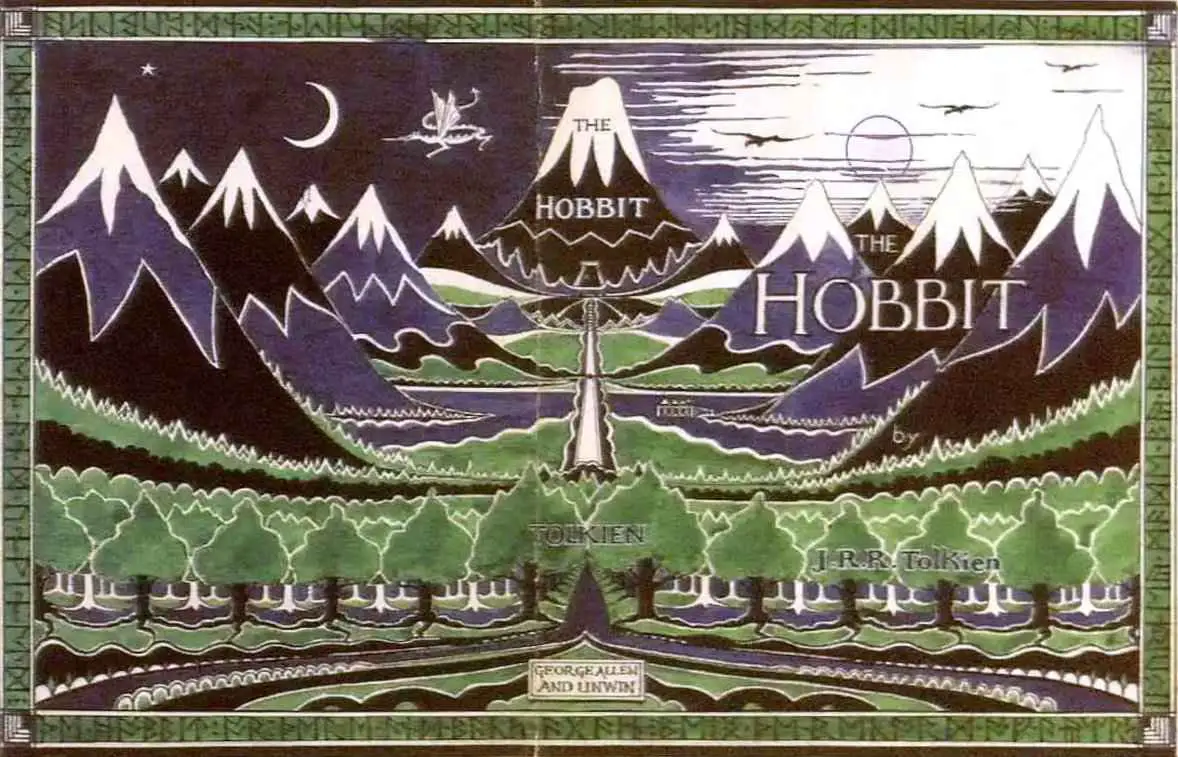

The Symbolism Of The Forest In 20th Century British Children’s Literature

The second chapter of Francis Spufford’s memoir of reading, The Child That Books Built, is called ‘The Forest’. Spufford makes the following points and more:

- In a literary forest you know that you can find all manner of wild creatures, travellers, knights and kings, youngest sons and so on. These other people and dangers are never far away, but in any particular story you may not intersect. The nature of the forest is that you are alone in it. Merlyn and Mole (from Wind In The Willows) will never meet. You have no resources except yourself.

- There are encounters, of course. The creatures you meet will be tests. You never come out the same person you were when you went in. (See The Three Types Of Modern Myth, in which the forest is an important setting.)

- Kenneth Grahame called his forest the ‘Wild Wood’. This is a concept that endured in Europe into the middle ages, a.k.a. The Old English Jungle. In these old stories (fairy tales, Robin Hood etc.) there was an almost moralised distinction between what was wild and what was tame. In the wildwood anything might happen. The Saxons represented a fearful disorder, thought of as wreckers and enemies of orderliness.

- The history of the British wildwood: Arrived at the end of the last Ice Age (c. 11000 BC), existed until it was cleared by humans as agriculture reached Britain. By 2000 BC there were big open spaces. By 500 BC half the wildwood had gone. Therefore, the wildwood had already gone by the time history began being recorded. So the death of the wildwood precedes history.

- The wildwood is a great setting for stories about orphans, which seem to be a necessity for children — a developmental stage in which we realise that we are in fact separate entities from our family.

- Hansel and Gretel and Little Red Riding Hood were moulded by the real landscapes of Germany and France respectively. These fairy tales travelled across the Atlantic to the English-speaking early settlers of America, where they resonated because these early settlers were themselves surrounded by forest again. But even the English liked these tales, even though technically it has been impossible to get lost in a forest in England since 1086 at the latest. (No English forest was longer than 4 miles across by that stage.)

- The forest is a metaphorical setting. It’s not a specific location, only a ‘vivid referent’ — ‘a tree line imprinted onto the imagination’.

- You can’t see far through a forest because it is thick. It’s ‘a place of formless impressions‘, ‘of aboriginal darkness and confusion‘. No one in a story has ever been taken into a forest and offered all the kingdoms of the earth.

- The inverse of a forest is a mount, or a desert. Jesus was tempted on a mountaintop and in a desert. Empty sands or gulfs of air are places where a traveller’s powers (divine or otherwise) are tested. But the forest is not to be mastered. The forest is therefore the great symbol of the unconscious. (See Bettelheim, The Uses Of Enchantment.) (Bettelheim was an as$hole who set psychology back a couple of decades. Look up his theories on the causes of autism. (tl;dr: Refrigerator Mothers)

- Forests are dark because the traveller hasn’t admitted all the darkness inside the mind. Fears haven’t been faced.

- Forests are full of robbers, waiting to jump out at you from behind a tree or a bush.

FORESTS IN THE VARIOUS SCHOOLS OF THERAPY

- Freud: A firmly individual thing, a private wood, which grows differently in everybody. It contains only those unacknowledged fears and desire that our own life has laid down there.

- Jung: A collective unconscious, a shared forest. A million separate paths lead into the one terrain. Instead of dreaming our own private dreams, we’re tapping into an elemental experience. This verges on mysticism and magic (if you let it be more than a metaphor). Robert Holdstock’s Ryhope Wood is an example of a Jungian forest.

- Jean Piaget was the first to study young children and how their minds work completely differently from those of adults. For example, young children (and fundamentalist religious folk) believe the natural world was arranged entirely for human benefit. A three-year-old’s world is magical. Three-year-olds are ‘in the woods’, before they’ve learned that the world operates in basically predictable ways.

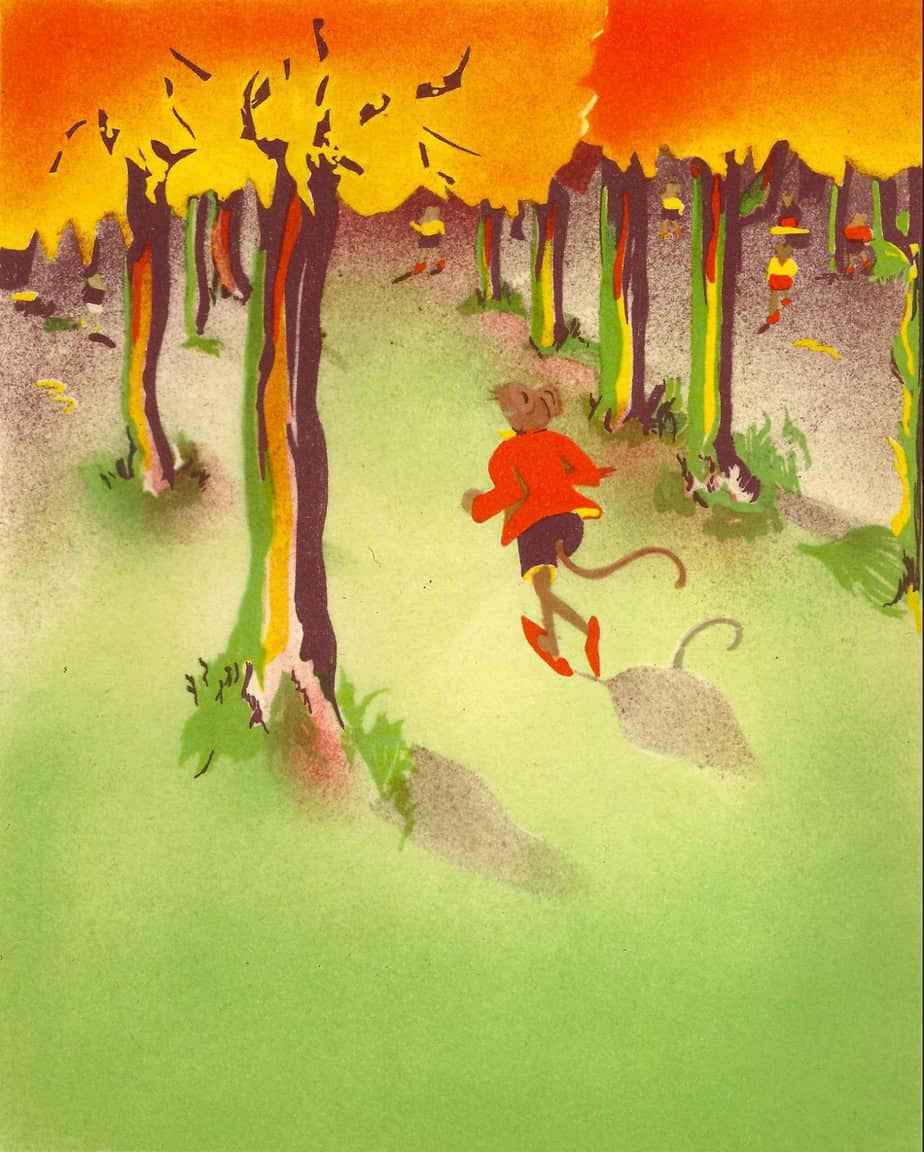

The Symbolism Of The Forest In Australian Literature

A peculiarity of Australian English is that ‘the bush’ can refer to what anyone else would basically call ‘a plain with nothing much on it in the way of shrubbery’. But aside from the ‘bush’, Australia also has quite a lot of forested land, unlike in modern England. It is still very much possible to get lost in the Australian forest (also in the bush).

The symbolism of the forest and its guardian monsters has flourished in the literature of Australia, where white settlement is very recent and where the settlers confronted a continent which appeared to them to be as much a wilderness as the cedar forest which Gilgamesh and Enkidu entered. The primary theme of white Australian writing, at least until the last few decades, has been the alienating and terrifying encounter with the land, but many Australian stories conclude on a far less confident note…The bush has evoked ambivalent responses from white Australians, but on the whole fear and uncertainty has outweighed delight. The white child lost in the bush is an iconic image in Australian art, and tales, such as the story of Eliza Frazer, in which lost Europeans are adopted by Aboriginal tribes and absorbed into their culture, grip white imaginations.

Deconstructing The Hero, Marjery Hourihan

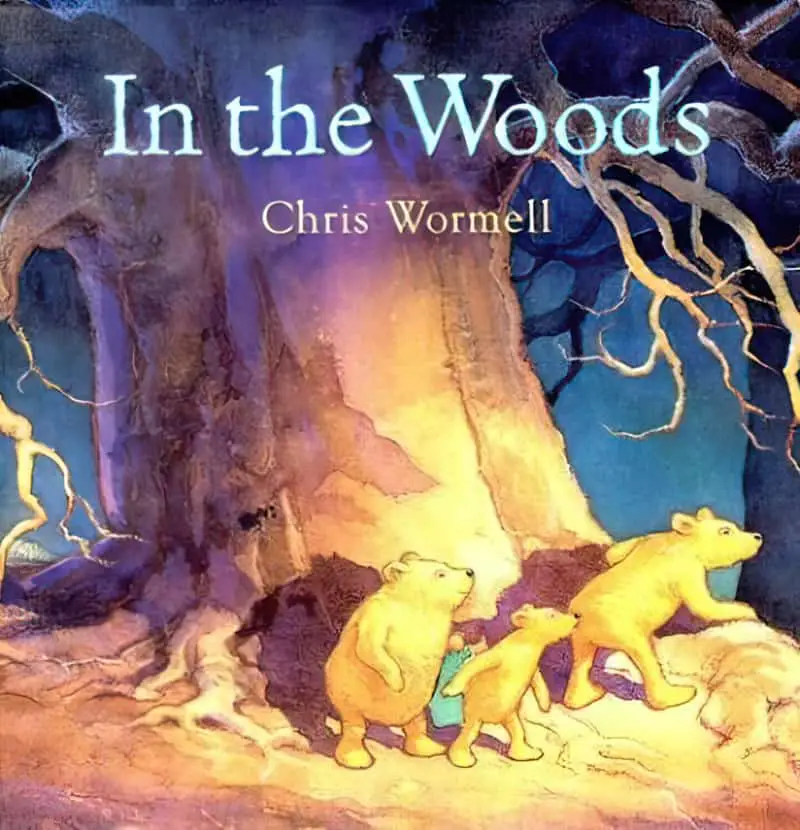

Even in books by Australasian authors, bears are likely to appear in the woods at any time. Especially if you’re having a picnic.

FURTHER READING

Forest and Tree Symbolism In Folklore

The Heart of the Forest: Why Woods Matter

The Heart of the Forest: Why Woods Matter (British Library, 2022) looks at threats to forest life across the globe. Dr. John Miller draws on literature, film and art to explore why woods matter to us, building on the ecological case for saving trees to raise the compelling question of their cultural value.

The Heart of the Forest explores four enduring ways in which we connect to the woods – through Refuge, Sacredness, Horror and Hope – making fascinating links between emotion and genre. For Henry David Thoreau, the woods are places beyond civilisation; for Ursula LeGuin and C S Lewis, they are loaded with otherworldly potential; and for those fleeing captivity, they can provide a welcome sanctuary. Woods can strike fear, they can inspire wonder, they can be lovely, dark and deep.

With full-colour illustration throughout, this book branches out into the British Library to find both the haunting and the hopeful in an unparalleled collection of books, manuscripts and photography. It tells a global story of how we understand trees, and its beautifully illustrated pages present a moving argument for conservation and renewal.

interview at New Books Network