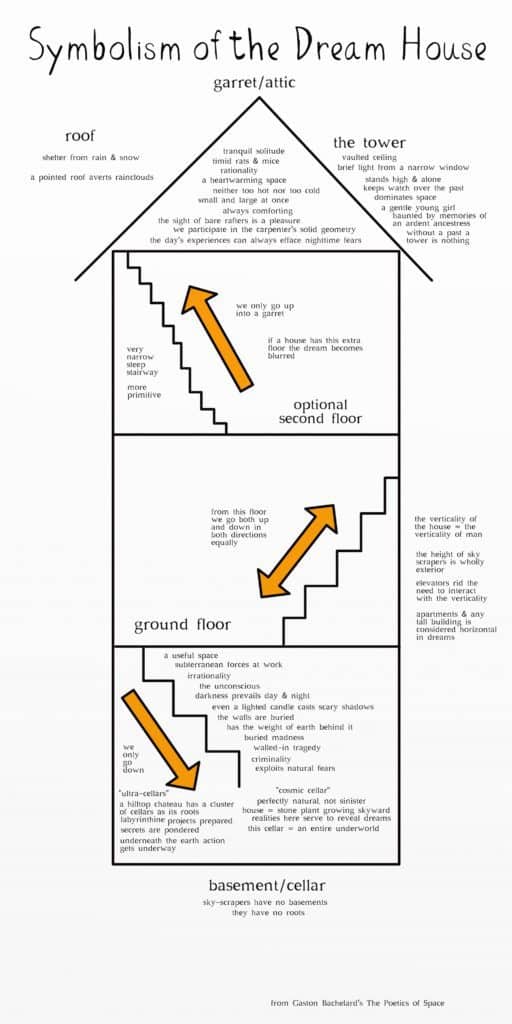

House symbolism is an interesting way of looking at a story. Have you noticed that houses as depicted in Western picture books tend to look the same? Two storied, bedrooms upstairs, slightly untidy but still Pinterest-worthy? There’s a reason for this. Each part of a house is symbolically unique. Gaston Bachelard talks about this in his famous book on architecture and philosophy, The Poetics of Space.

- The Symbolism of Stairs and Attics

- The Kitchen as Metonym for Familial Happiness

- Symbolism of Basements

House As Human Body

Some commentators (e.g. Scherner) interpret houses in dreams as stand-ins for the human body. The windows, doors and entrances are the entrances into the body cavities. The facades are smooth or provided with balconies and projections to which to hold. In anatomy the body openings are sometimes called the body-portals.

Buildings As Characters In Fiction

There is a problematic trope in which the large house correlates to a large, overbearing woman. The trope intersects with fatphobia and misogyny. For an example of this trope see the children’s animated feature film Monster House. What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? is another example of the same trope.

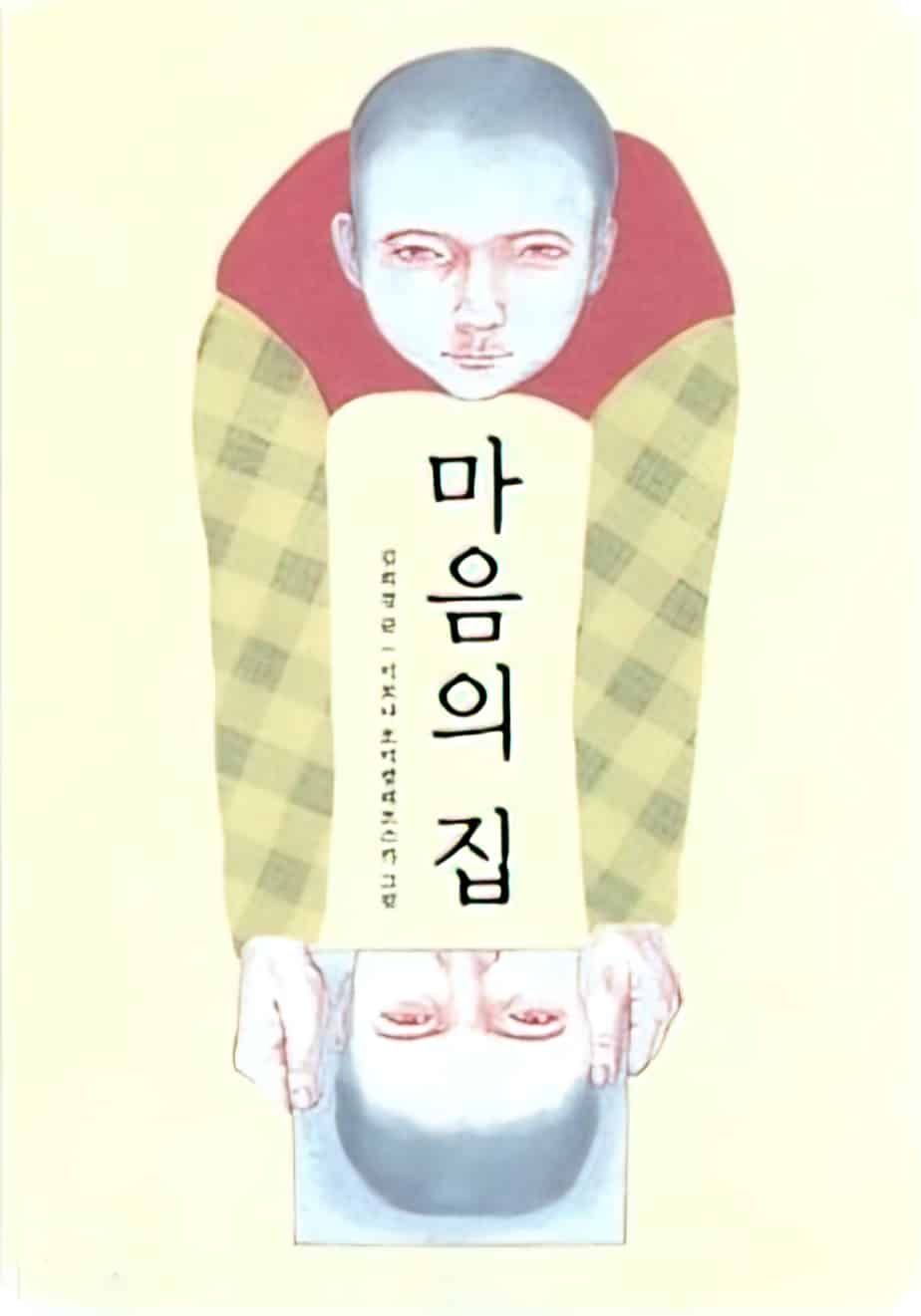

The mind itself is often imagined as a house. Korean writer Kim Hee-kyung took this metaphor and created a picture book which won the 2011 Bologna Ragazzi Award.

I thought our minds are very much like a house. That’s the metaphor I used for this book.

Kim Hee-kyung

Home As Metonym For Family

In the middle ages houses were simply places to seek refuge and sleep. There was no conception of children, and no concept of family in connection to this place of crude shelter. Today we think of home quite differently. We strive to make it comfortable (another newish concept) and we strive to fill it with the people closest to us.

Women and Houses

In the suburban house…there is “a room for everyone but the wife/mother, who, it is assumed, had the whole house. … [thus] there is no space in the suburban dream house (Heilbrun).

SCHWENINGER, LEE. “Reading the Garden in Gilman’s ‘The Yellow Wallpaper.’” Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, vol. 2, no. 2, 1996, pp. 25–44.

Off-kilter Houses

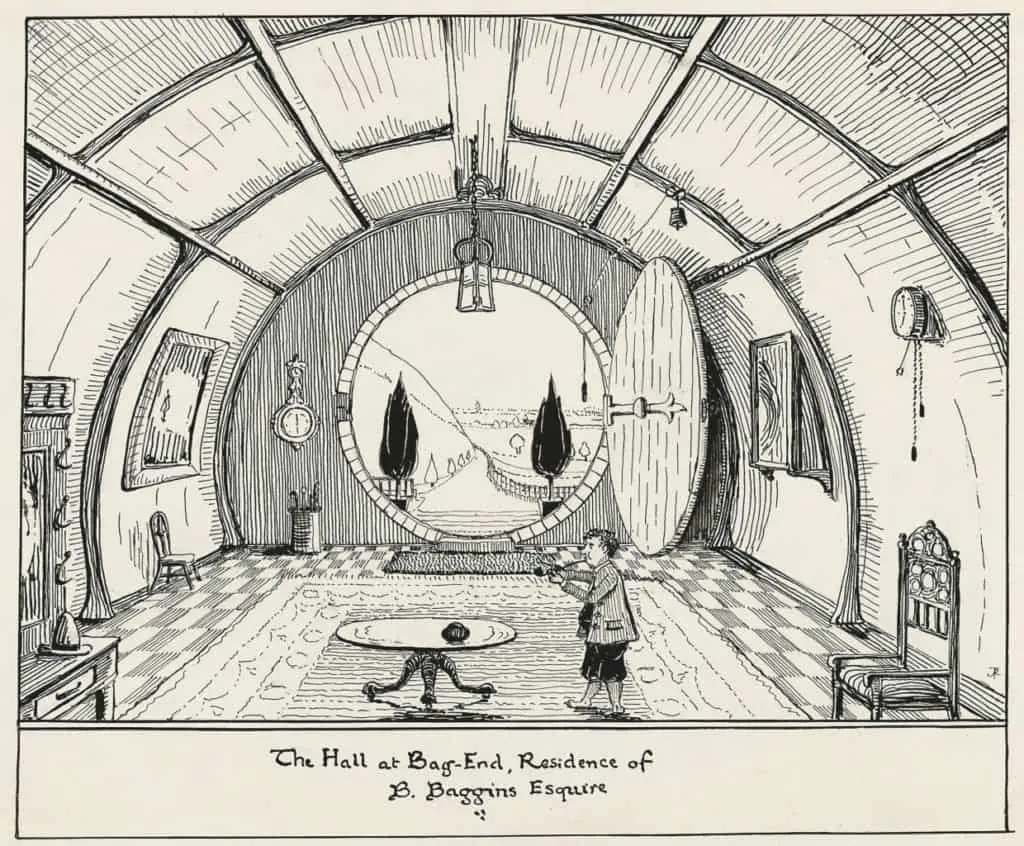

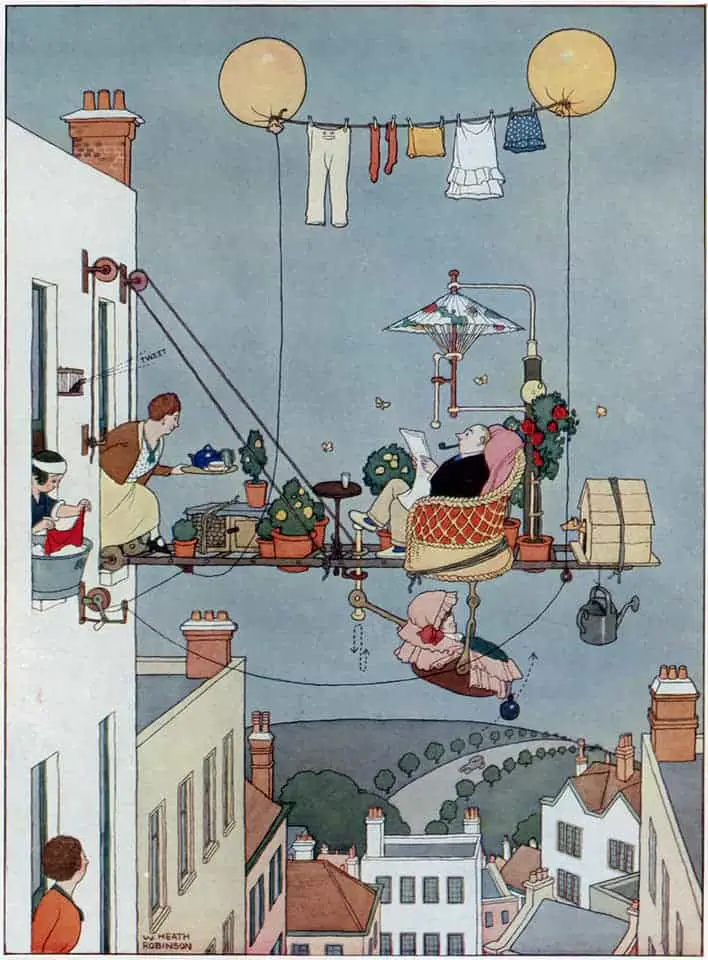

Dwellings in fantasy don’t always look like the rectangular structure we know and love.

For example, Bilbo’s circular house feels particularly cosy, in stark contrast to the jagged mountains in the distance.

Another example of extreme oddity is the Gingerbread House of Hansel and Gretel.

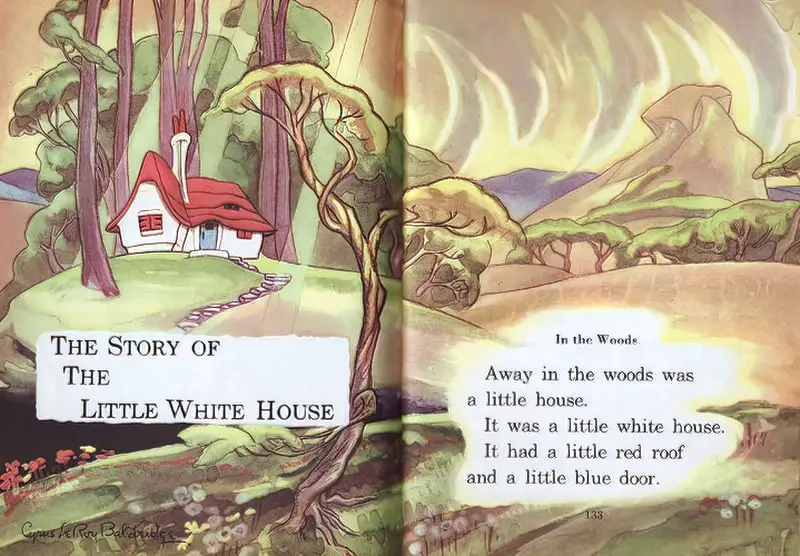

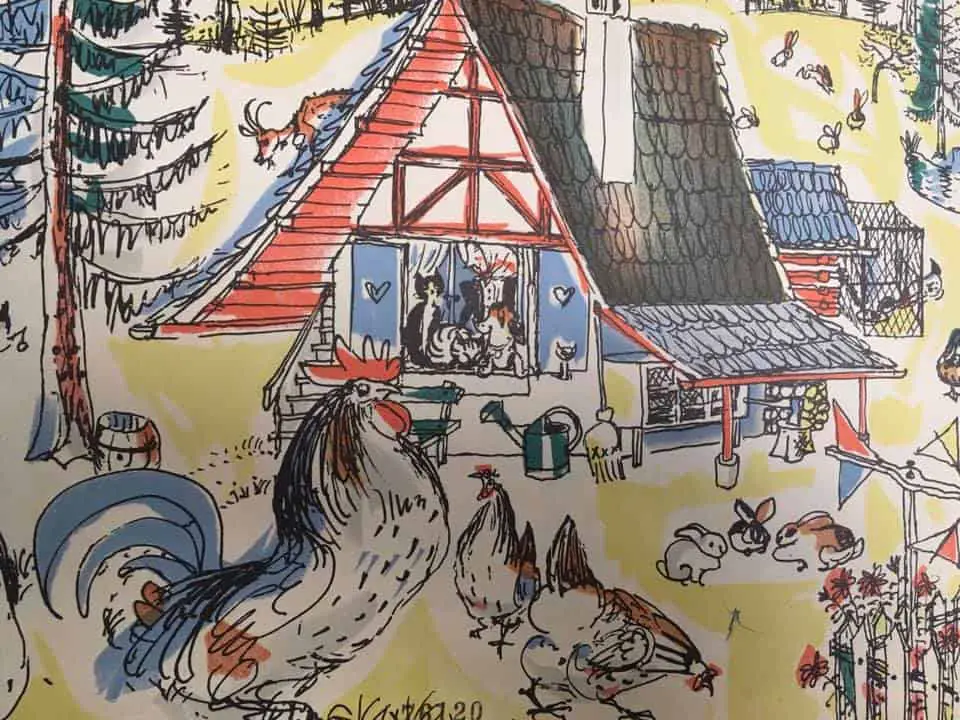

The Cosy Picture Book House

Do you have a dream house that exists only inside your head? Perhaps it’s somewhere you hope to build one day, or a mixture of great spaces you’ve been to in your lifetime. If you were asked questions about this dream house, I wonder how specific you could get?

- How many bedrooms does it have?

- How does one get from one bedroom to another?

- Where do the inhabitants keep their clothes?

- Their shoes?

- What would I find in the larder?

- Which direction does it face?

- If I flew into the air above your dream house, what does the surrounding area look like?

As Gaston Bachelard says, quoting Rilke in The Poetics of Space, those of us who keep dreamt-up houses in our heads haven’t worked out the details. Details such as: How does one get from one room to another without a connected corridor?

[The imagined dream house] is not a building, but is quite dissolved and distributed inside me: here one room, there another, and here a bit of corridor which, however, does not connect the two rooms, but is conserved in me in fragmentary form. Thus the whole thing is scattered about inside me, the rooms, the stairs that descended with such ceremonious slowness, others, narrow cages that mounted in a spiral movement, in the darkness of which we advanced like the blood in our veins.

Rainer Maria Rilke, quoted in The Poetics Of Space

The house I had imagined inside my head wouldn’t necessarily work. And the architecture of the house is essential to the plot, which is certainly not true of many other picture books.

I wonder if it’s common for picturebook illustrators to draw a floor plan when illustrations are set largely inside a house. It really helped me out a lot, to spend half an hour visualising the entirety of Roya’s world within the story, down to the wallpaper.

Once I’d sketched a layout of the apartment, illustrations progressed at a faster pace*. I didn’t have to consider the interior decor, of her non-imaginary world, at least. I’ve heard art advice to the effect that you need to understand the entirety of a subject even if you’re only going to be depicting a single facet. I was imagining a banana when I heard that advice, but it certainly applies to houses and floorplans. Otherwise you’re liable to draw a house without any doors.

(By the way, I decided the toilet and bathroom are communal, downstairs.)

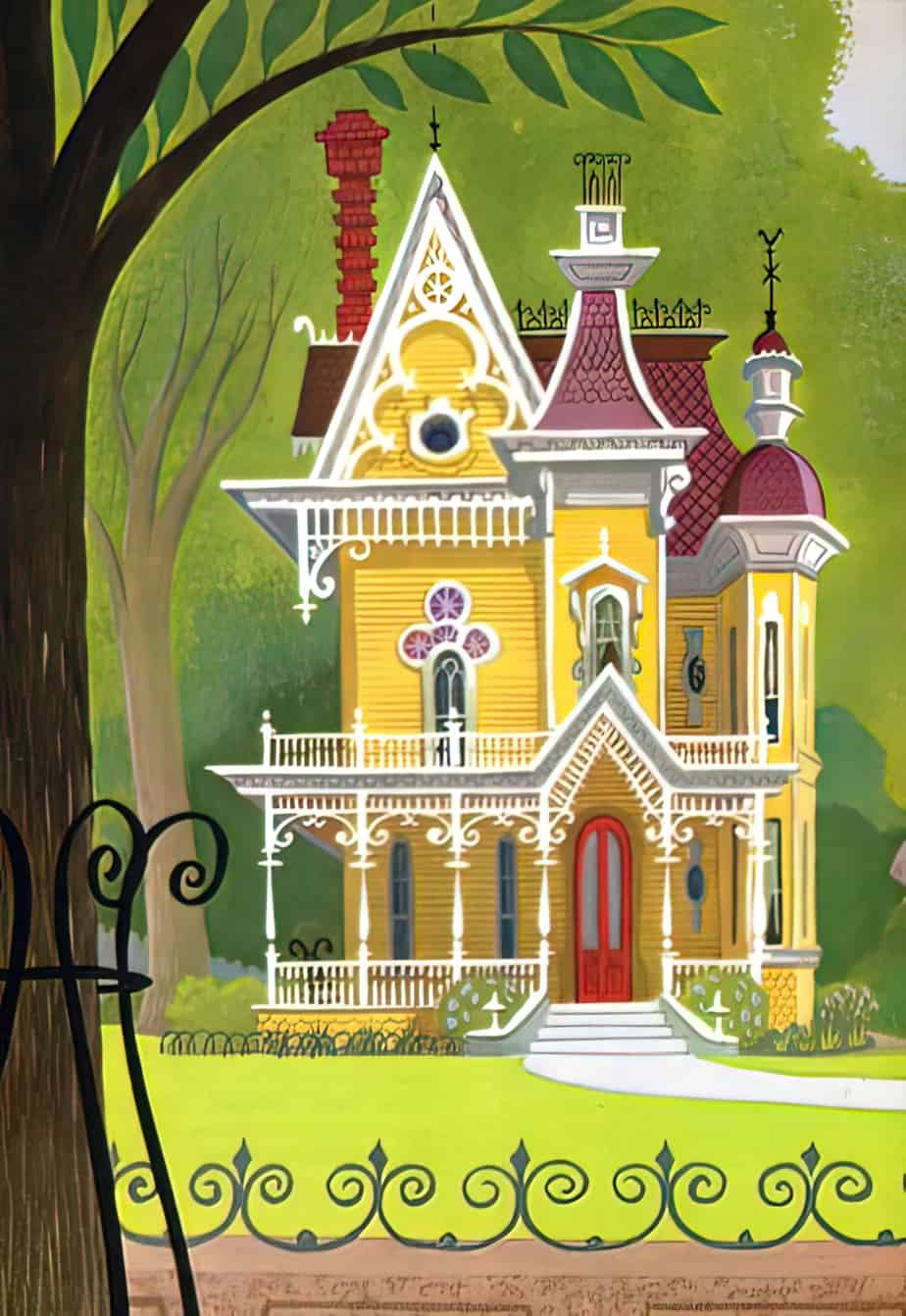

Header illustration is the classic picture book house, from The Plant Sitter by Gene Zion, 1959; illustrated by Margaret Bloy Graham.

Of all the stories you loved in childhood, which of the houses would you most like to live in? Was it, by chance, a ‘bustling’ environment? Was it quirky or intriguing or very large?

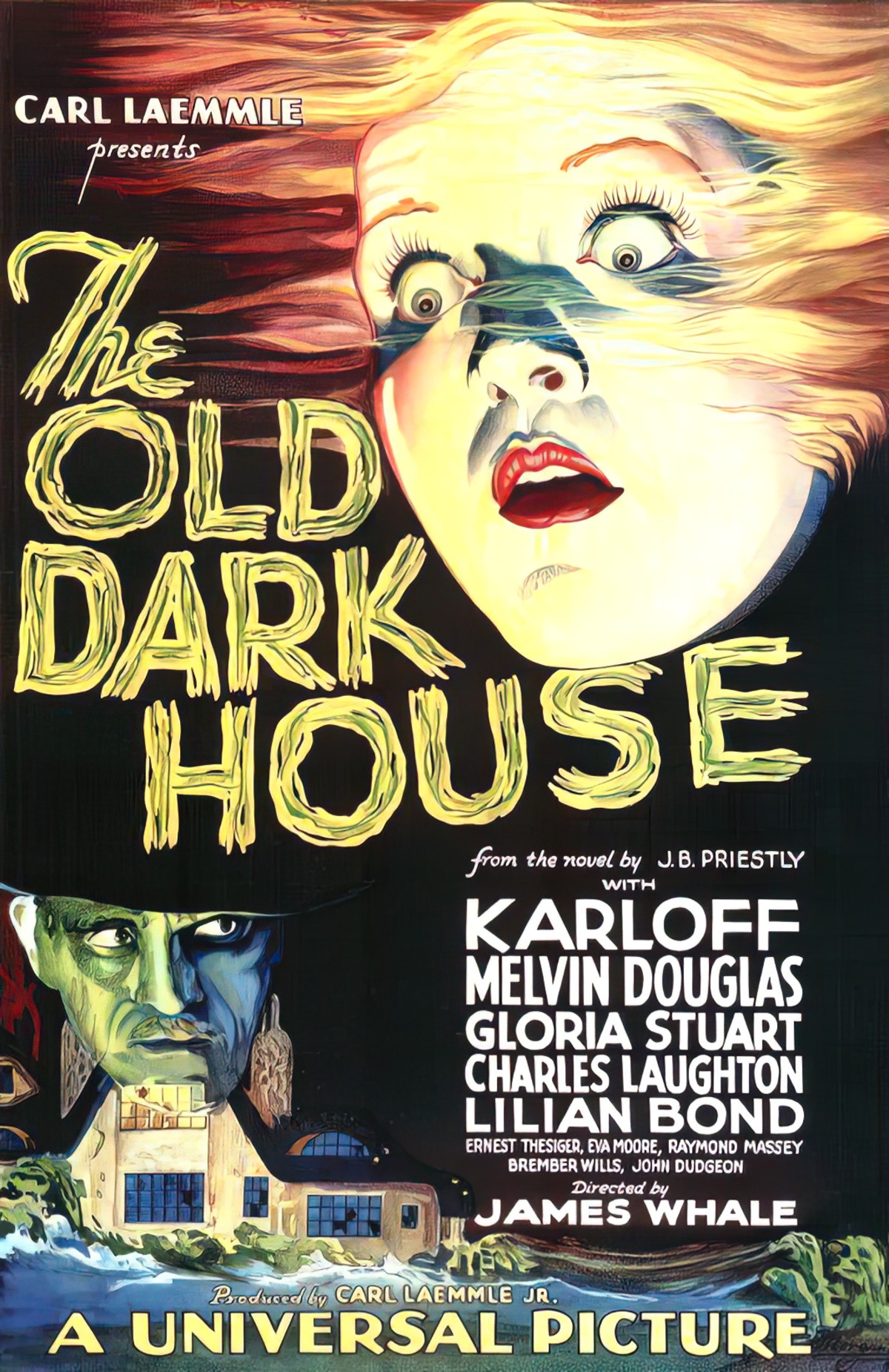

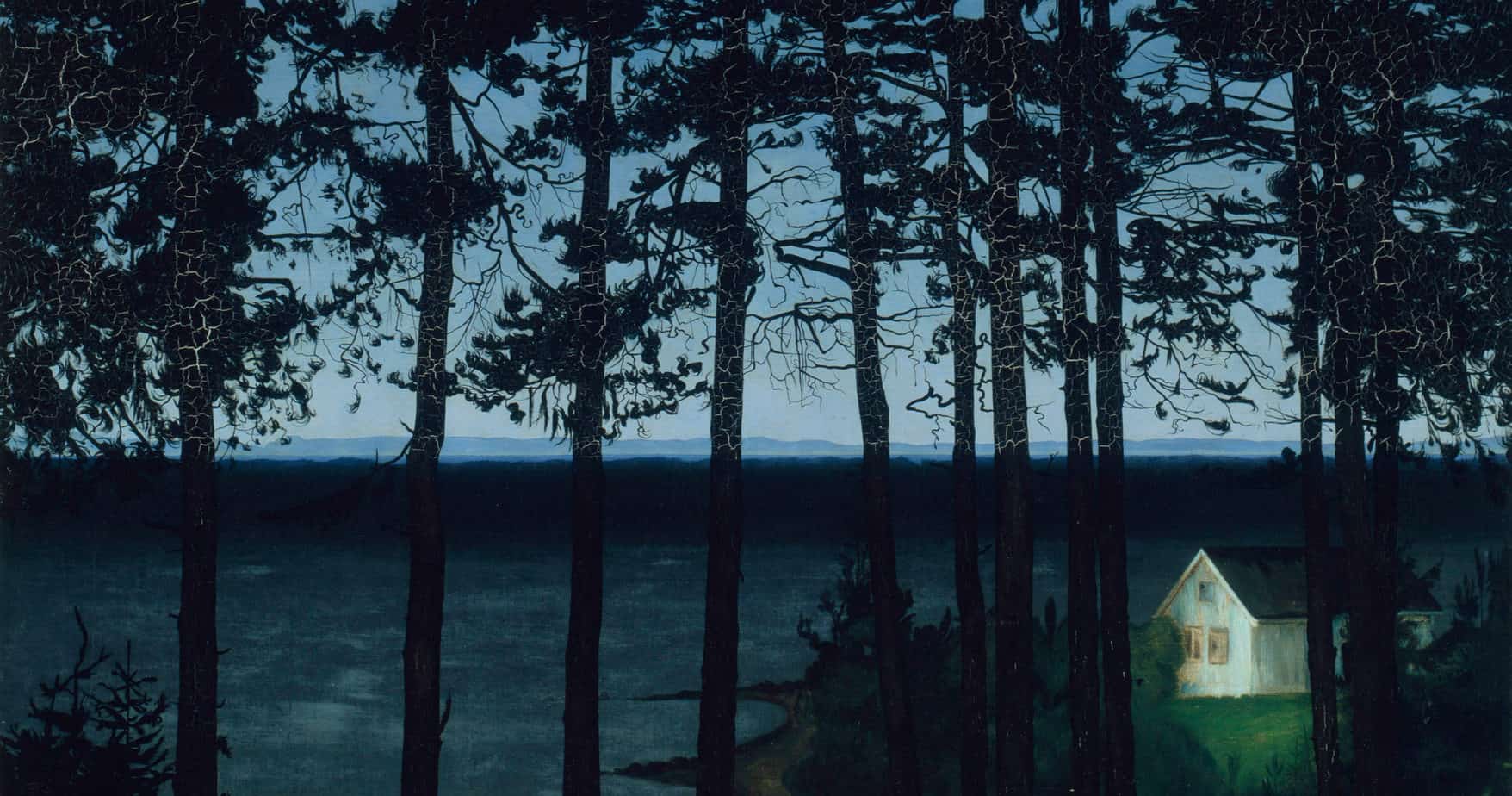

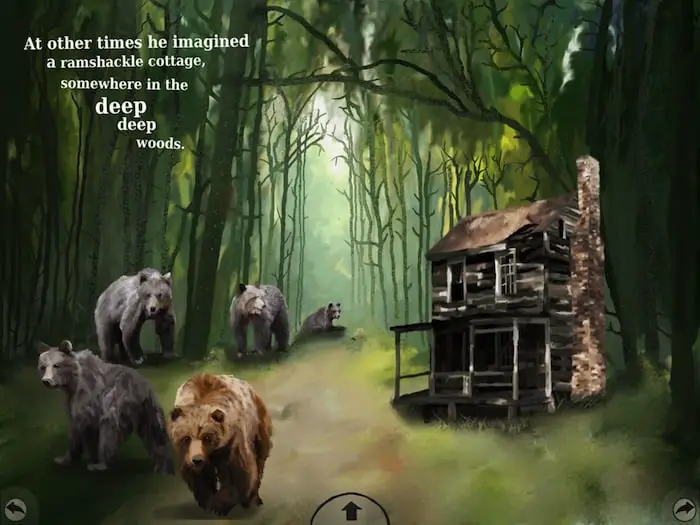

The Gothic House

When storytellers take the dream house to its horror extreme you get the terrifying mansion which features heavily in Bluebeard stories and its descendants.

The dark, terrifying house contrasts the warm, welcoming house important to children’s stories with a home-away-home structure. Without a home base, modern stories cannot have happy endings.

Interestingly, a Medieval audience wouldn’t have thought in this way. In Medieval Europe, the house did not equal the home, and shelters were just that — places to sleep. If there was furniture, it wasn’t made for comfort. The very concept of comfort is a modern one. Even until Jane Austen’s time, ‘comfort’ as a word was used quite differently and meant strengthening, support and consolation rather than the modern experience of sitting in a nice, padded chair. The concept of ‘child’ is also modern. In the Medieval era, offspring were sent out into the world as apprentices from about the age of seven. Most people lived in shacks but not houses; houses were not used as metonyms for family as they very much are today.

Scary houses are not always dark. White gothic exists, such as depicted in the cold house below — opulence without comfort. Modern films and TV shows achieve a similar effect by making use of large houses made largely of windows.

However, if you take the coldness and put it outside, the cosy house becomes even more cosy. It is now an oasis of warmth.

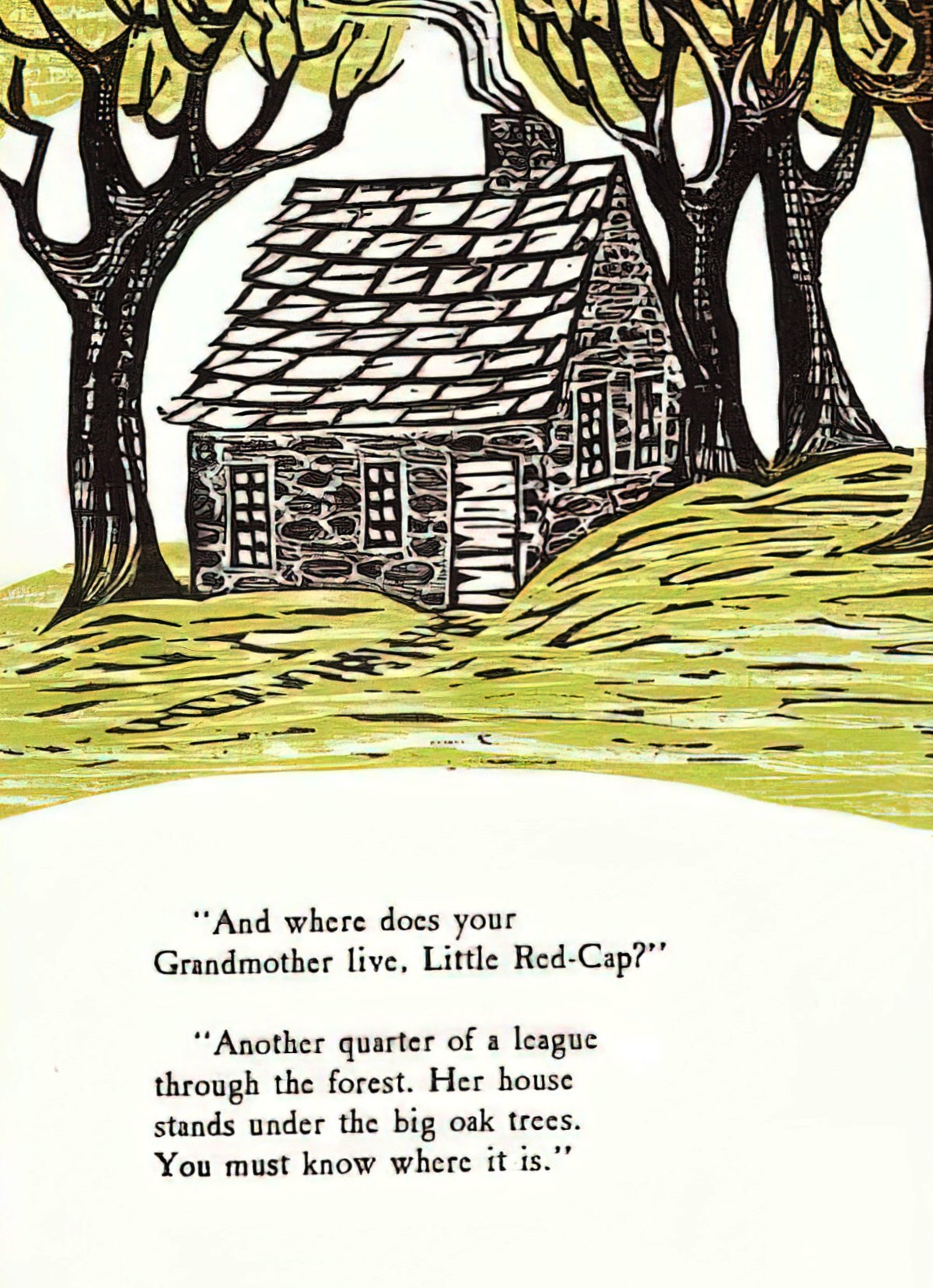

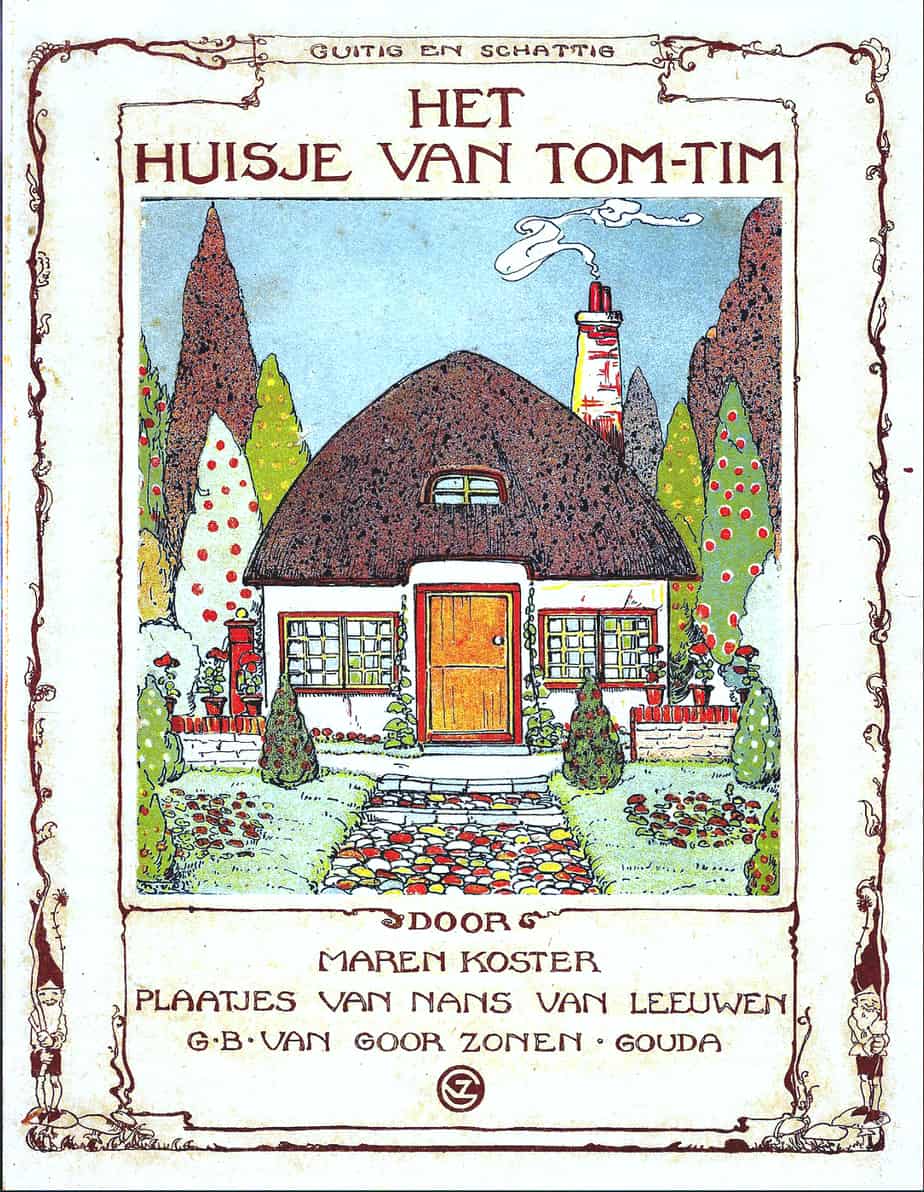

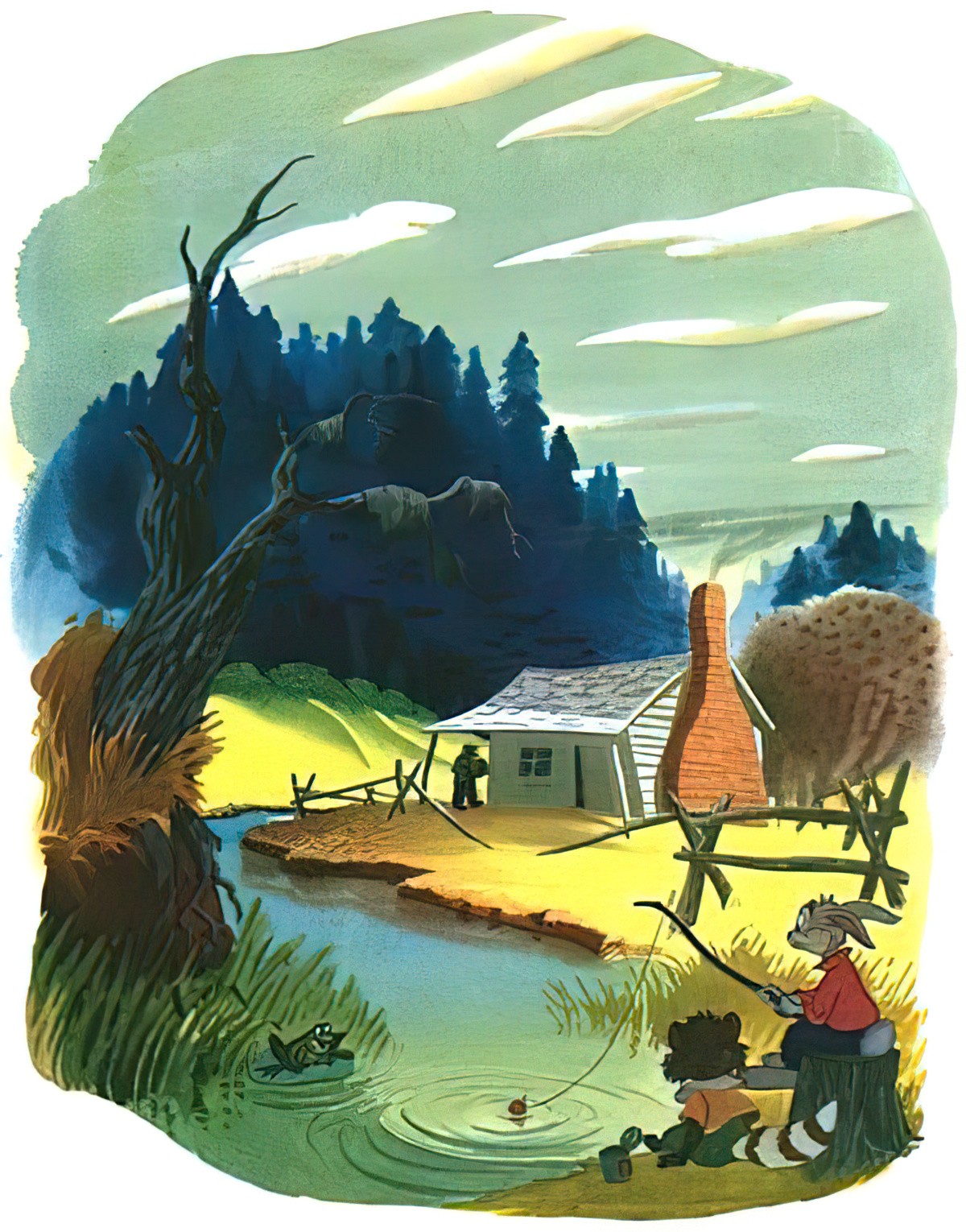

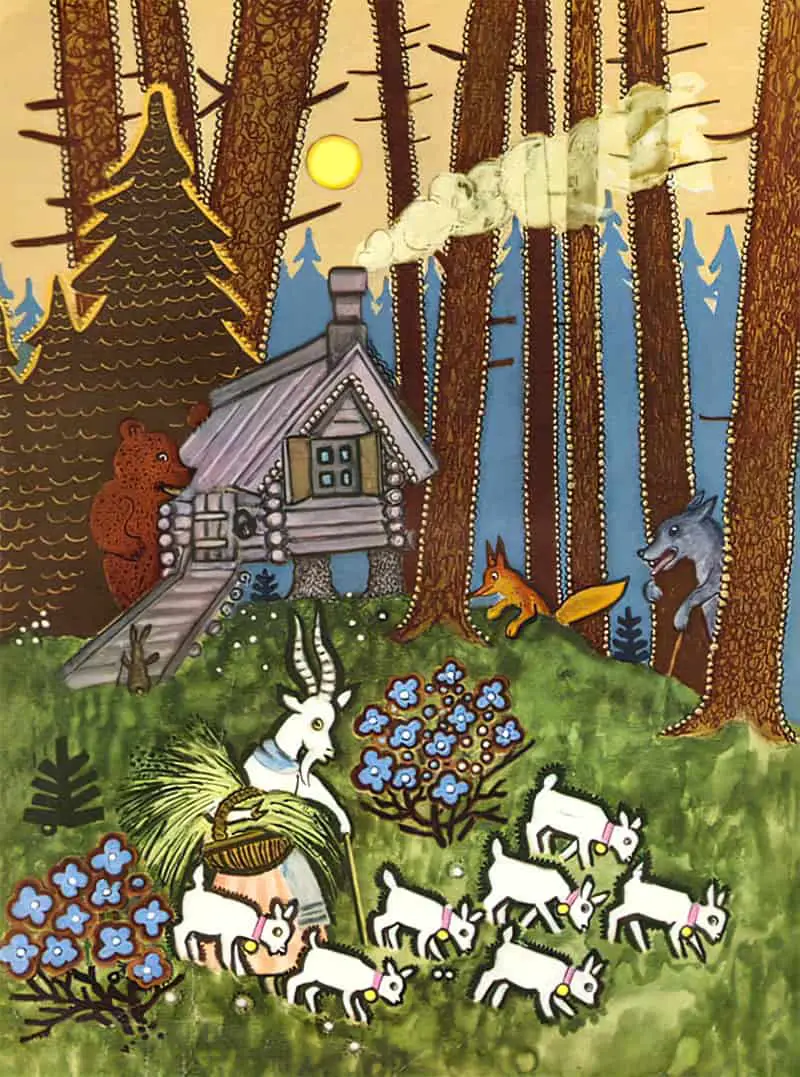

THE DREAM COTTAGE

The dream cottage exists near woods, in that liminal space between forest and savannah.

The house suppresses Fanny’s dreams and tries to force her to settle in marriage. Once Fanny is in the house she finds out that her immediate family is dirty chaotic and classless. Fanny is left in conflict over whether she should rush to marry her suiter Henry or wait for her true love Edmond. The house represents Fanny’s past and future if she is to move forward Fanny must endure the uncomfortability of living in the house.

The symbolism of the cottage in Mansfield Park from Objects of Romanticism

Which of the following cottages would you like to sleep in under moonlight and why all of them?

When you think of a cottage today, you’re probably thinking of a smaller than average house which charming, rustic decoration, perhaps honeysuckle grows outside. There’s probably enough land outside for a well-tended garden. But the word cottage hasn’t always referred to the size and mood of the house. First cottages were small, then they were quite large, now they are small again.

late 14c., “a cot, a humble habitation,” as of a farm-laborer, from Old French cote “hut, cottage” + Anglo-French suffix -age (according to OED the whole probably denotes “the entire property attached to a cote”).

Etymology Online

The main thing about those really old cottages: cotters lived there. Cotters were farm labourers or tenants who occupied a small house on a larger property in return for labour.

The term ‘cottage industry’ later meant an industry run from home. In order to run a business from home, the house has to be pretty large, actually.

Later, in America, ‘cottage’ referred to how many servants were employed at the house. From there, the word ‘cottage’ once again became associated with ‘small’:

In 1870, fully 60 percent of all the gainfully employed women in the United States worked as servants. Andrew Jackson Downing differentiated between houses and cottages according to the number of servants that they contained–anything with less than three servants was a cottage. Nevertheless, as early as 1841, Catherine Beecher was arguing that more compact houses were necessary since “as the prosperity of this Nation increases, good domestics will decrease.” Indeed, this is what happened, and by 1900, there were less than half as many servants in the United States as in England; more than 90 percent of American families employed no domestics.

Home, Witold Rybczynski

Cottages traditionally have thick walls, well suited to cold climates but not to hot, humid ones as they’re inclined to trap the air inside. Unlike a cabin, which is made of wood (probably logs), cottages are made of a variety of different materials, depending on the region and economic situation.

People from far away, from Boston and Philadelphia, discovered the beautiful bay. They bought up land near the water and built large houses that they called cottages.

Barbara Cooney, Island Boy

Cooney demonstrates in the passage above that the cottage — the true cottage, not the grand house disguised as cottage — is the picture book ideal. Happiness is found in a cottage. Whereas the large house is often cold and lonely and scary, the cottage is never so.

In a cottage you can achieve the Christian ideal of making do with little. A cottage is unable to house superfluous possessions.

THE DREAM BUNGALOW

A bungalow is a low house having only one storey or, in some cases, upper rooms set in the roof, typically with dormer windows. However, the word came from South East Asia (Bengal, to be specific), where it actually means a detached house with more than one storey. Unlike a cottage, they don’t have those thick walls. You might say a bungalow is a subcategory of cottage but for tropical climates.

Within Britain, you’re more likely to find cottages inland but bungalows beside the sea.

Here in Australia, the California bungalow was popular after the first world war, when Australians started to watch Hollywood movies and obviously liked the look of this kind of house. Both California and much of Australia are well-suited to this design, with its verandah stretching most of the way around the building.It is raised above ground by a metre or more so that the dwelling does not easily flood. Steps lead up to the front door, and in most cases a large veranda surrounds the exterior of the home so you can sit on the porch to catch a tropical breeze. The interior only uses one level adorned with wide hallways and large windows to help distribute air throughout the home.

Some of them have attics, but they’re just as likely to have a dormer window, or just a vent designed to look like one. (That’s why they’re called one and a half storey houses.)

New Zealand has a lot of California bungalows, too, built around the same time.

But a luxurious house like the one below is also called a bungalow.

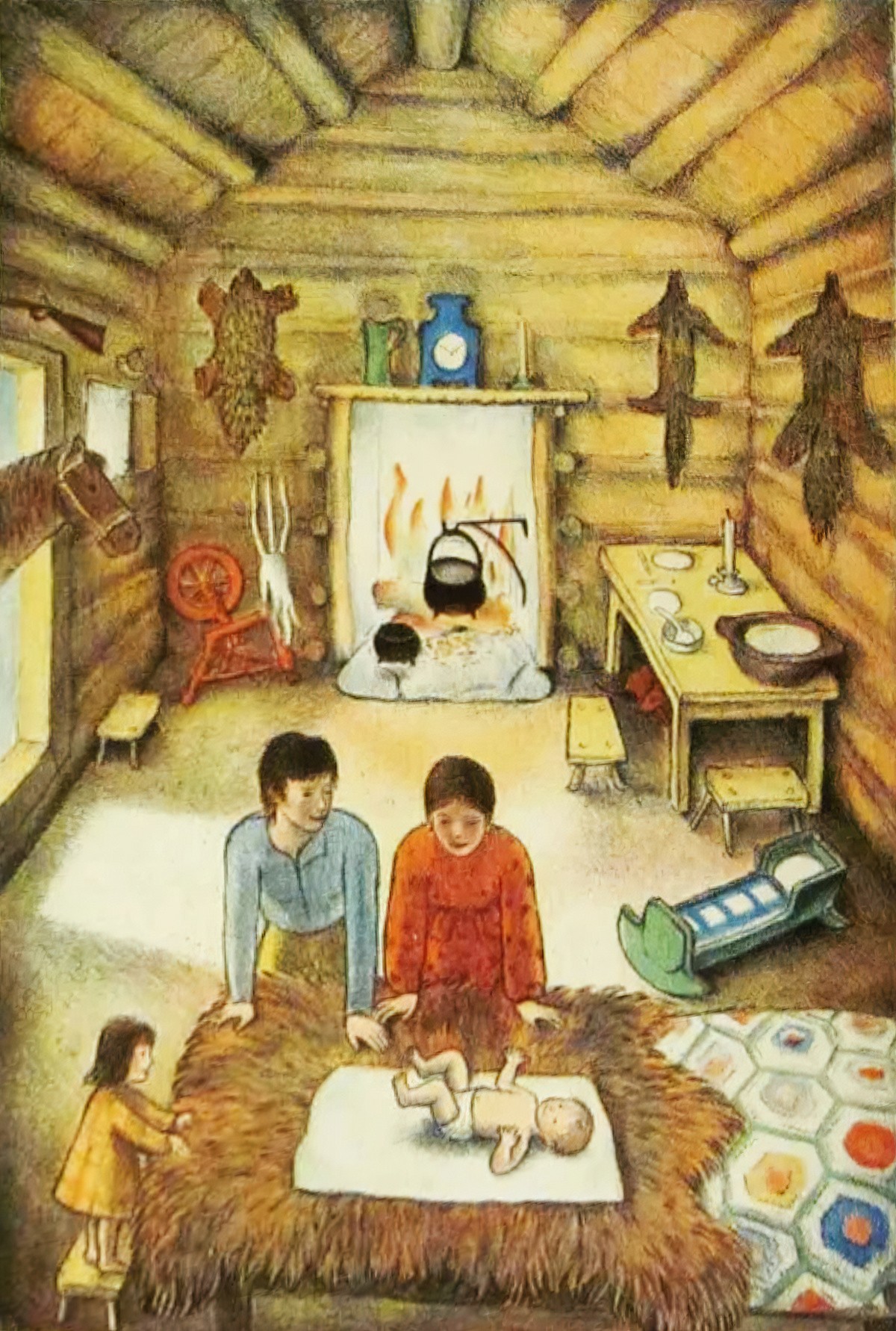

THE DREAM CABIN

The log cabin is an American symbol.

Cabins can be rustic and simple or they can be luxurious. The most luxurious are luxurious in a very specific kind of way: luxury reminiscent of turn of the (20th) century wealth, especially the decades between 1890 and 1930.

The log cabin setting…has the affected, cedar-stump rusticity that used to characterize rich men’s hunting lodges at the end of the [19th] century.

Home, Witold Rybczynski

Rybczynski noted that that the 1980s version of a luxurious cabin left out the mounted animal heads on the walls. More lately, the stuffed mounted head on the wall is a feature of horror and comedy settings — and best of all, horror comedies.

SEE ALSO

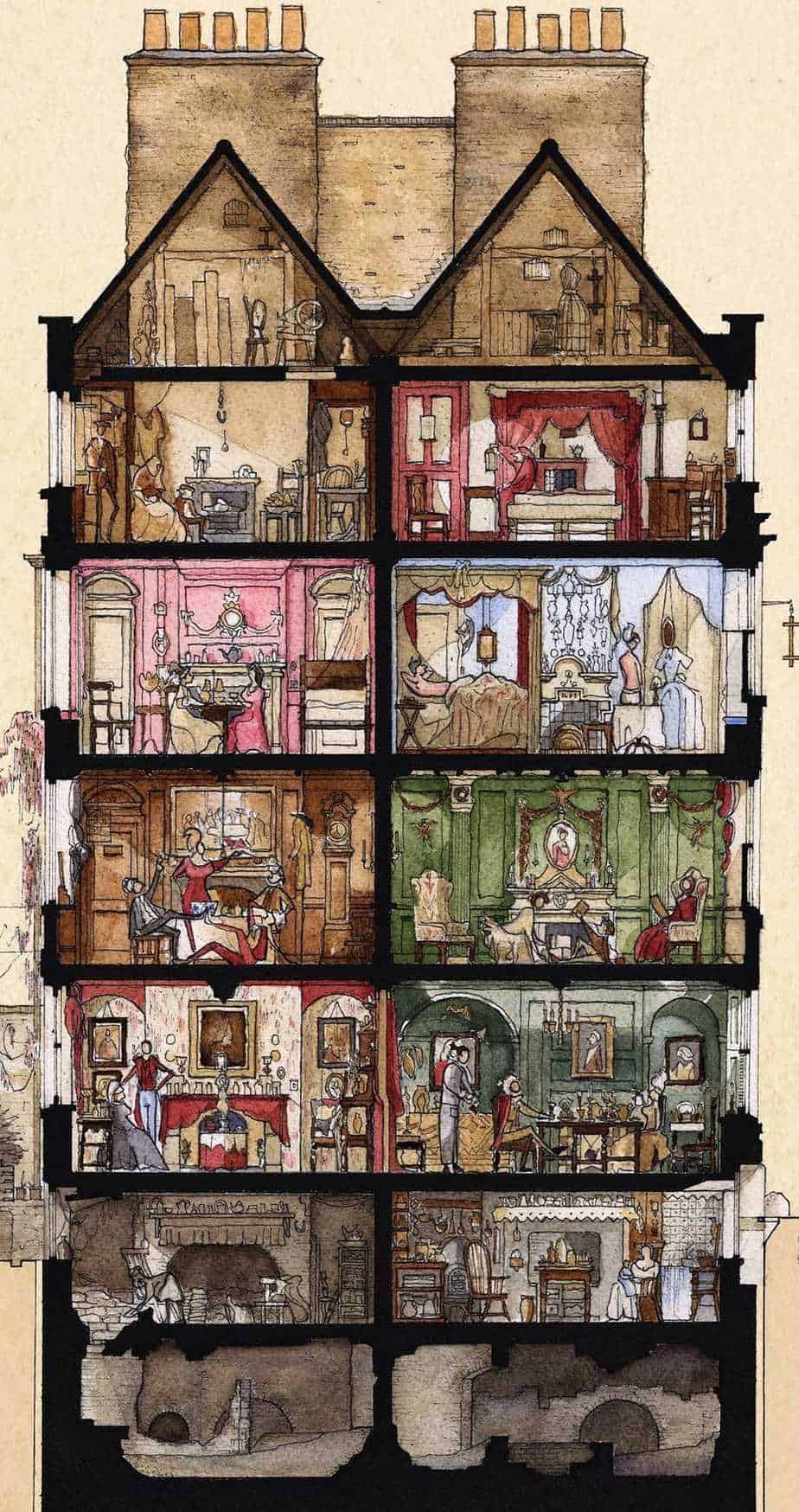

The devil’s daughter rows to Edinburgh in a coffin, to work as maid for the Minister of Culture, a man who lives a dual life. But the real reason she’s there is to bear him and his barren wife a child, the consequences of which curse the tenement building that is their home for a hundred years. As we travel through the nine floors of the building and the next eight decades, the resident’s lives entwine over the ages and in unpredictable ways. Along the way we encounter the city’s most infamous Madam, a seance, a civil rights lawyer, a bone mermaid, a famous Beat poet, a notorious Edinburgh gang, a spy, the literati, artists, thinkers, strippers, the spirit world – until a cosmic agent finally exposes the true horror of the building’s longest kept secret. No. 10 Luckenbooth Close hurtles the reader through personal and global history – eerily reflecting modern life today.

What Would Be The Houses Of Filmmakers If They Were Based On Their Own Films