Vessels or containers are as important for the space they contain as well as for any material they hold. Containers tend to be associated with women. As motifs running throughout a story they can also symbolise physical or emotional containment, either self-driven or imposed upon a character from outside.

When Did Humans First Use Containers?

Containers are associated with gathering, sharing and femininity.

Containers [like digging sticks] were probably developed early, and the first ones may have been made of strong leaves or bark. They were used to carry one’s baby on one’s back, to carry water during long gathering journeys, and to carry the fruits of these journeys back to the settlement. The invention of the container was a major step in human evolution. It provided the first step between humanoids and animals, because it permitted gathering rather than foraging. Animals forage — that is, they collect food, eating it as they go. Gathering is the collecting of food so one can carry it elsewhere and save it for later. The container suggests cooperation, because the food is meant to be shared; it permits movement of a troop to a new location, and even over long distances in which food supplies are unpredictable. It also permits settling into a home base, however temporary. And this step too was probably taken by females: ‘It was the mothers who had reason to collect, carry and share plant food; at this time, males were likely still foragers, eating available food as they went,’ writes Nancy Tanner. Improved containers meant that gathering hominids could migrate. They did: the earliest hominid fossils outside Africa were found in Indonesia, and are approximately 1.9 million years old.

Beyond Power: On Women, Men & Morals by Marilyn French

The Promise and Intrigue of Containers

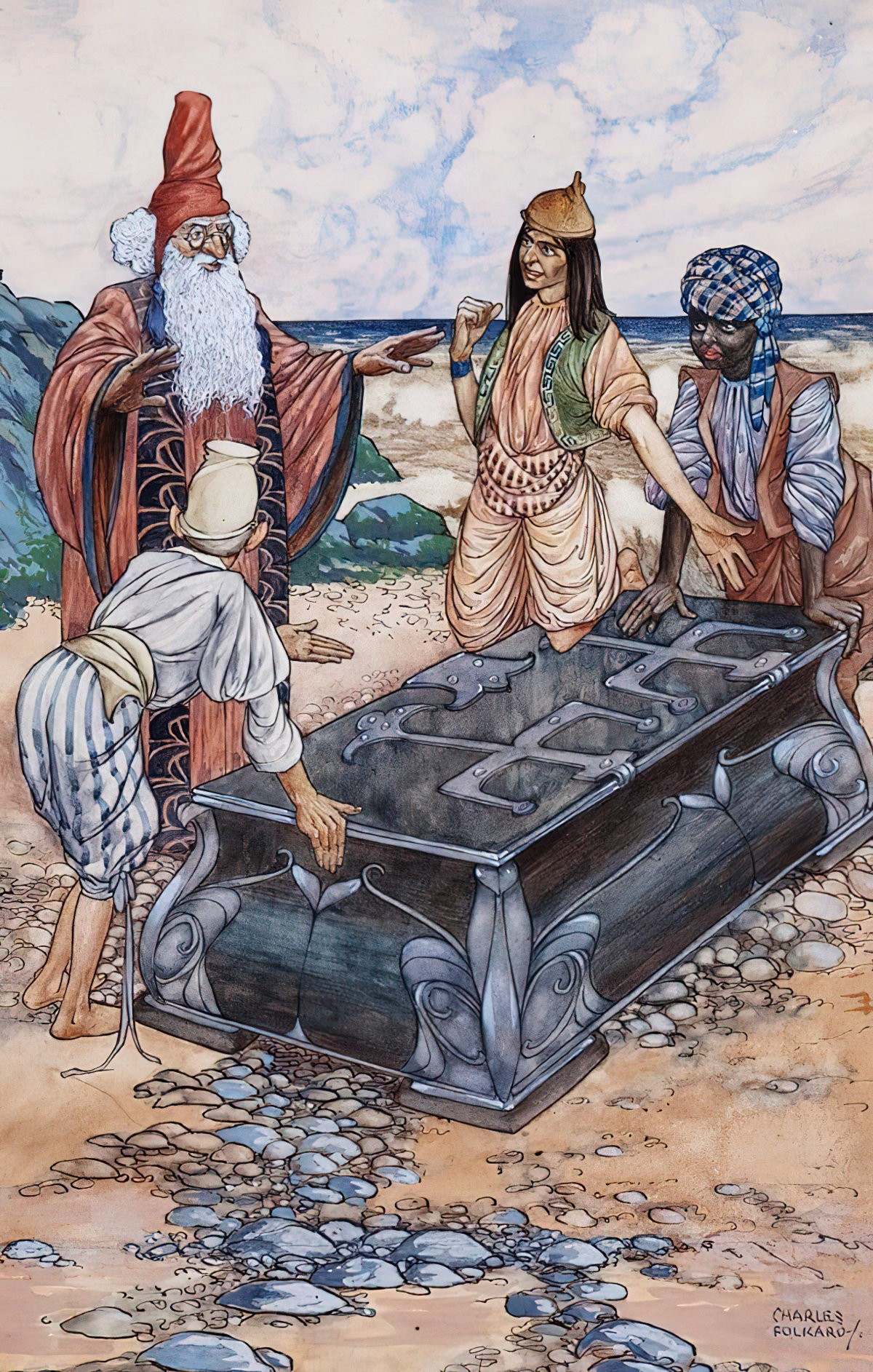

The box containing treasure was once used to market cereal. This imagery wouldn’t be utilised by marketers today, and I deduce that the box of treasure was a stronger symbol for early 20th century audiences than it is for us.

How to create optimal mystery? Promise something but don’t show it. This is why we wrap presents. It’s why artists show characters looking at something mysterious out of the frame. It’s why writers drip feed something gradually, slowly bringing a mysterious person or item into view, building up to the big reveal.

Containers are the symbolic embodiment of all that. An enclosed container holds something but we don’t know what. Not until we open it.

CONTAINERS WHICH GRANT WISHES

Stories about containers which, once opened, reveal an entity which will fulfil your every desire can be seen around the world.

From China we have “The Magic Cask”.

If you’d like to hear “The Magic Cask” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “The Magic Cask” was published March 2020.

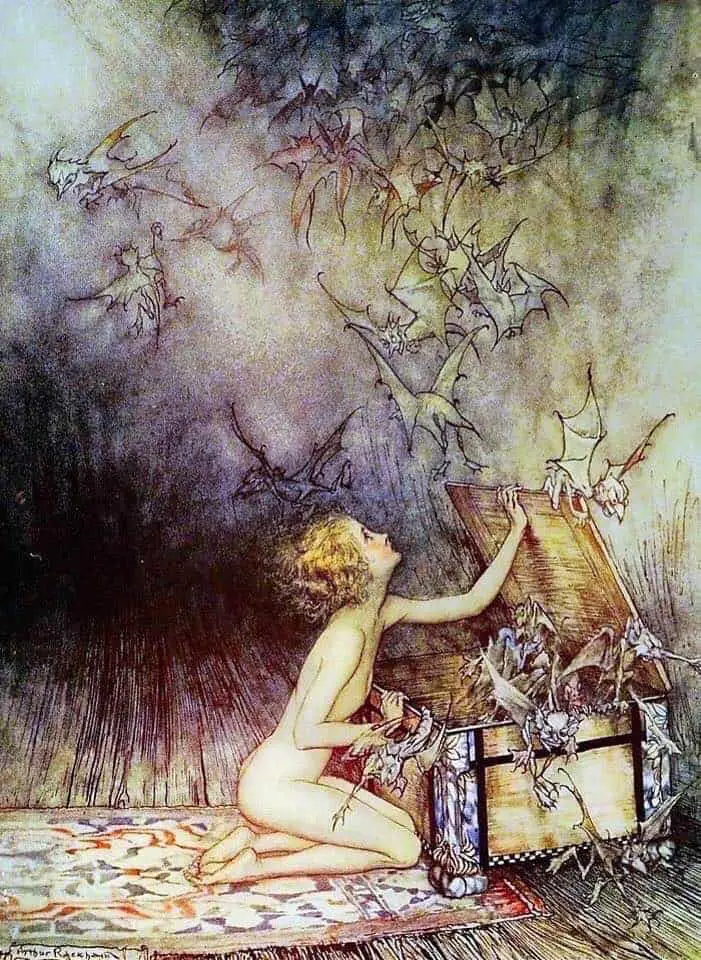

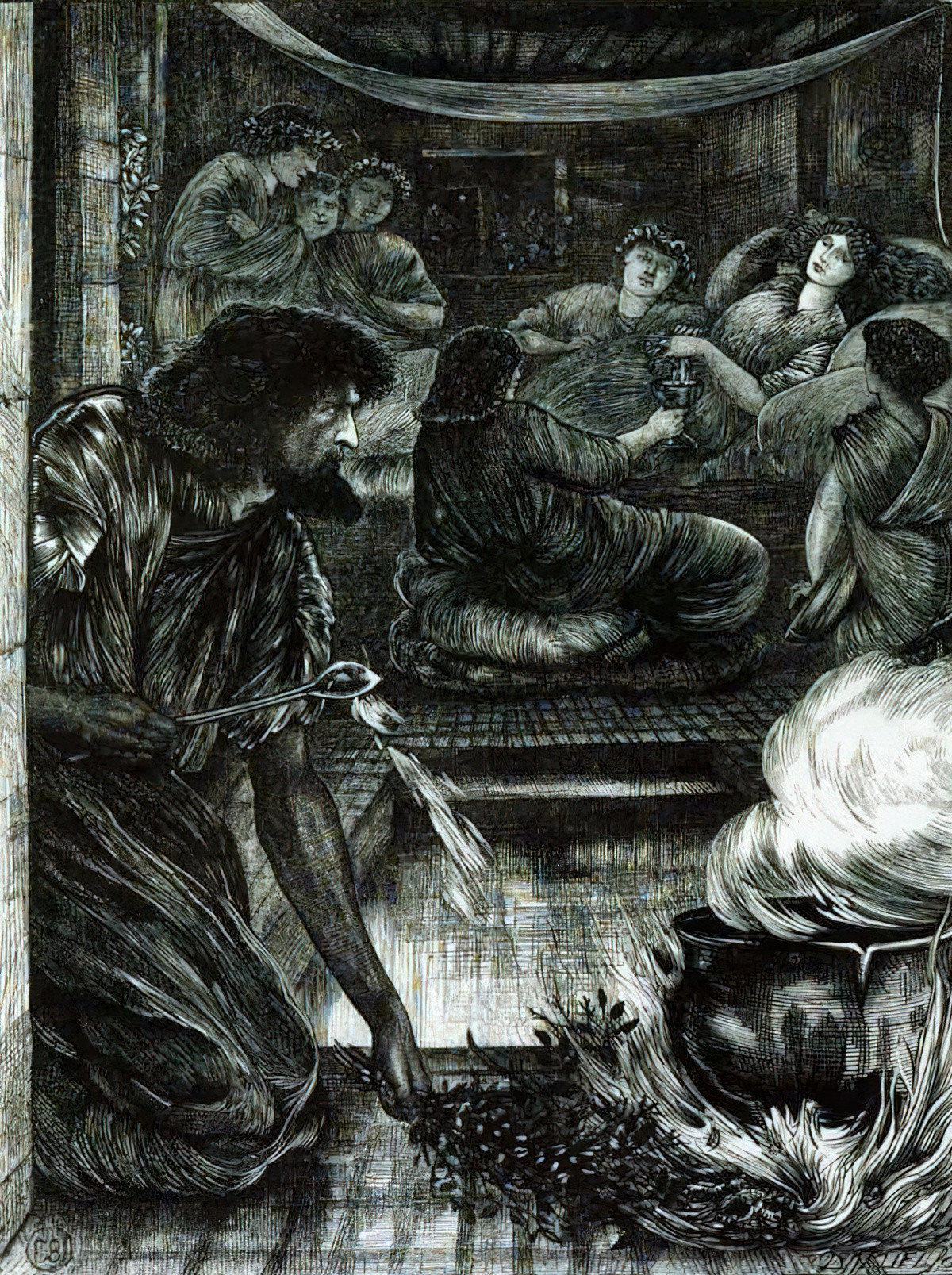

PANDORA’S BOX, OR JAR, AND ALSO EVE

Across the history of storytelling, many narratives exist to teach less powerful people (including women) that if you find something locked away in a chest, you should just leave it there. The story of Adam and Eve is the stand-out example of this story, but we also have Pandora’s box.

Many male painters since have painted Pandora naked (forgetting about the silvery robe Hesiod gave her in the eighth century BCE (while at the same time seeing to become aroused by his own creation):

- Jean Cousin

- Jules Lefebvre

- Paul Cesaire Gariot

- William Etty

- John William Waterhouse

- et al

The story of Pandora is a permutation of the story of Eve in the Garden of Eden. In art, the two women are sometimes conflated. For instance, Jean Cousin’s Eva Prima Pandora (c. 1550), Henry Howard’s The Opening of Pandora’s Vase (1834), Rossetti’s portrait of Pandora (1871). Rossetti’s remains the most famous of these.

In both the Eve and Pandora stories, a woman gets the blame for unleashing evils into the world. This has always struck me as vastly unfair.

Let’s talk about Eve for a moment, and why it was never her fault.

- God created the tree

- God put the tree right where the humans he created could take it, with the apple in easy picking-reach

- God made the fruit look delicious, with an eye-catching colour

- God created the persuasive talking snake

- God only warned Adam not to eat the apple. No one actually told Eve not to touch it, though some may assume Adam passed on the message, since the word of God in many churches passes from God to male church leader to husbands and only afterwards to wives.

Meanwhile, Adam had heard the prohibition directly from God and shared the apple with Eve. If anyone’s more culpable in this narrative, surely it’s Adam.

If you agree that Eve was unfairly blamed, just wait until you hear about Pandora.

- In early versions of this story, there was no box and Pandora did not open it. The box first appeared in the story in Works and Days by Hesiod (Greek), later translated into Latin by Erasmus, more than 2000 years later. Erasmus had trouble translating ‘pathos’, which referred in Greek to a big ceramic storage jar about a metre high and not very stable. It’s possible Erasmus was confusing Pandora with Psyche (who does carry a box). In any case, jar became box.

- Those big storage jars were about a metre tall, narrow at the base, and not exactly stable. They did not have screw top lids. They were easy to knock over. Without a tight lid, it’s not as if anyone could keep evils inside a big ceramic jar let alone be responsible for letting them out.

- Artists have since depicted Pandora opening a box, sometimes out of curiosity, sometimes out of malice. In either case, the evils of the world become Pandora’s fault.

Bluebeard fairytales (and all their descendents) have the same message: If you know something is locked away LEAVE IT LOCKED AWAY. With the benefit of hindsight it’s easy to see why these cautionary tales existed: To leave power in the hands of those who already had it.

18th century children’s story Rosamund and the Purple Jar is anti-climactic precisely because the vessel holds something pretty, then disturbing, and ultimately contains nothing Rosamund wants. Her hopes are dashed. Victorian children were supposed to learn from this didactic story not to place too much hope on the unseen and the unknown. More generally, pretty appearances can disappoint by their lack of true substance.

In her short story “Prelude“, Katherine Mansfield makes use of containers as a motif throughout, liking young Kezia to her grandmother via a shared proximal placement of small containers.

For another short story with a box as significant motif see “U.F.O. In Kushiro” by Haruki Murakami.

The Third Casket

A ‘third casket’ is similar in concept to Pandora’s box, and is found in many fairytales. The first and second caskets contain riches but the third unleashes bad stuf like storms, death, general devastation.

These days, in many cultures, we divide the year into four distinct parts (by season). Stories about three caskets indicate a different division — a division into thirds. Two good seasons, one bad.

Arks

If you think of ‘ark’, you’re probably thinking of Noah’s Ark, or possibly the Ark of the Covenant. An ark is a big container that holds very valuable objects. In this way, an ark symbolises a treasure chest. It might be massive (as in Noah’s) or it might be small (as in the ‘ark’ that Moses was found in, floating in the reeds). The commonality is that an ark’s contents are precious.

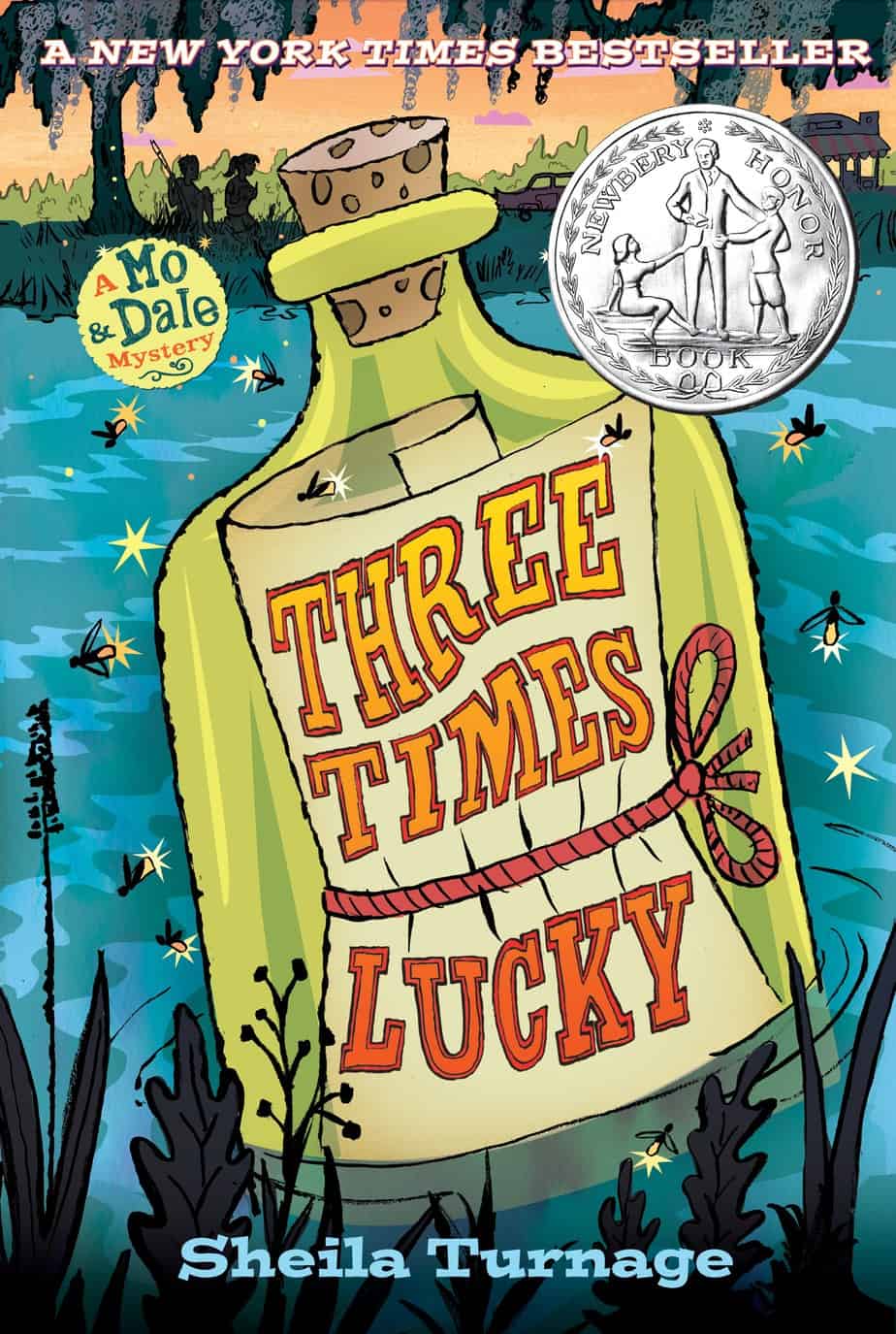

The bottle is one of the symbols of salvation, probably because of the analogy (of function rather than of shape) with the ark and the boat.

A Dictionary of Symbols by J.E. Cirlot

Witch Bottles

In the 17th century, people started burying bottles around their yards to ward off evil. Inside the bottles: hair/pins/urine/chicken feathers/bits of plants and various bits and bobs. These were known as witch bottles. They are to break the power of a witch over their victim.

Science in this period was pretty different from ‘science’ as we know it today. These witch bottles were basically in accordance with scientific thought of the era.

Witch bottles were also thrown into lakes, the sea and other places thought to be affected by witches. Everyone used them differently, according to private symbolic ideas. But we can access these ideas using folkloric research and sort of make sense of how people thought they worked. A witch bottle contained some sort of ‘spirit essence’ which had been coerced into that bottle. Location is vitally important in determining the function of that bottle.

Some bottles were thought to have been laid down by witches themselves. These bottles were not apotropaic, but were designed to cast a curse upon somebody.

If you came across a bottle, it may have been put there by a witch. So there was a proper way to dispose of it, rather like a bomb disposal unit. One does not simply break a witch bottle. In line with the message of the Pandora’s Box category of tales, it was thought that if you break a witch bottle horrible things would happen — vegetation would die and so on. NEVER EVER THROW IT INTO A CESSPOOL OR RUBBISH PIT. Break it over a fresh south flowing river or stream, where the pernicious fluid can mingle with pure currents and be imperceptibly but irrecovably wasted.

Some bottles are thought to have an anthropomorphic element to them, containing its own heart (animus).

Perhaps some bottles, for example the one containing the chicken feather, may have been thought to take pestilence away. (Maybe their chicken flock had been infected/infested and they didn’t know what else to do.)

(Listen to a podcast about witch bottles here, from Dr Peter Hewitt.)

Container as Private, Secret Space

In the 17th and 18th centuries, domestic corridors and closets, multiplying bedrooms and staircases, secluded chambers and servant’s bells manifested new architectures of secrecy, as well as new relations between masters and house staff. These new spatial orders might have afforded greater privacy (or secrecy?) to the elite, yet “the average London servant,” Amanda Vickery reminds us, “had no settled space to call their own.” Instead, many carried a portable lock box. While householders tended to maintain an assemblage of distributed hiding places around the house, assistants and lodgers often stored their secret (or private?) matters in locked trunks, chests, and closets (Meanwhile, in the U.S., some enslaved people buried valuable property under their floorboards, and embedded secret messages and escape routes in hand-crafted quilts).

Encrypted Repositories, Shannon Mattern

The Bag of Holding

The name of this trope comes from Dungeons and Dragons:

The Bag of Holding is a specific portable item which is Bigger on the Inside than it is on the outside. Much bigger. It may not look it, but that’s because it contains Hammer Space. Because the holding capacity of the bag comes from internal Hammer Space, a thoroughly-packed Bag of Holding will weigh no more than a full normal bag. Odds are, it will weigh no more than an empty normal bag.

Because of the sheer amount of goods you can store in one, trying to find something specific usually results in a Rummage Fail. Except, of course, in videogames where time itself will stop to let you go through your inventory in peace.

TV Tropes

The Cabinet of Curiosities

The word ‘cabinet’ originally described a room rather than a cabinet (and is still used to mean ‘room’ when we’re talking about Parliament buildings). Originally, a cabinet of curiosities was a big room in a rich person’s house containing all kinds of treasures — sort of like a private museum. The first cabinets of curiosities appeared in the 16th century. In fact, these rooms were precursors to museums. People who travelled were in the best position to set them up, e.g. merchants.

When cabinets became collections held in pieces of furniture (today’s usual meaning of ‘cabinet’), they were designed to be as interesting to look at as possible. They were highly ornamental, decorative and housed many disparate things. The idea was to represent the entire world in miniature. Interest came from the juxtaposition of many different objects.

Cabinets of curiosities were also show-off items, showing how rich you were, how cultured, how well-travelled.

Over the centuries, artifacts from these collections have proven invaluable to historians, naturalists and archeologists.

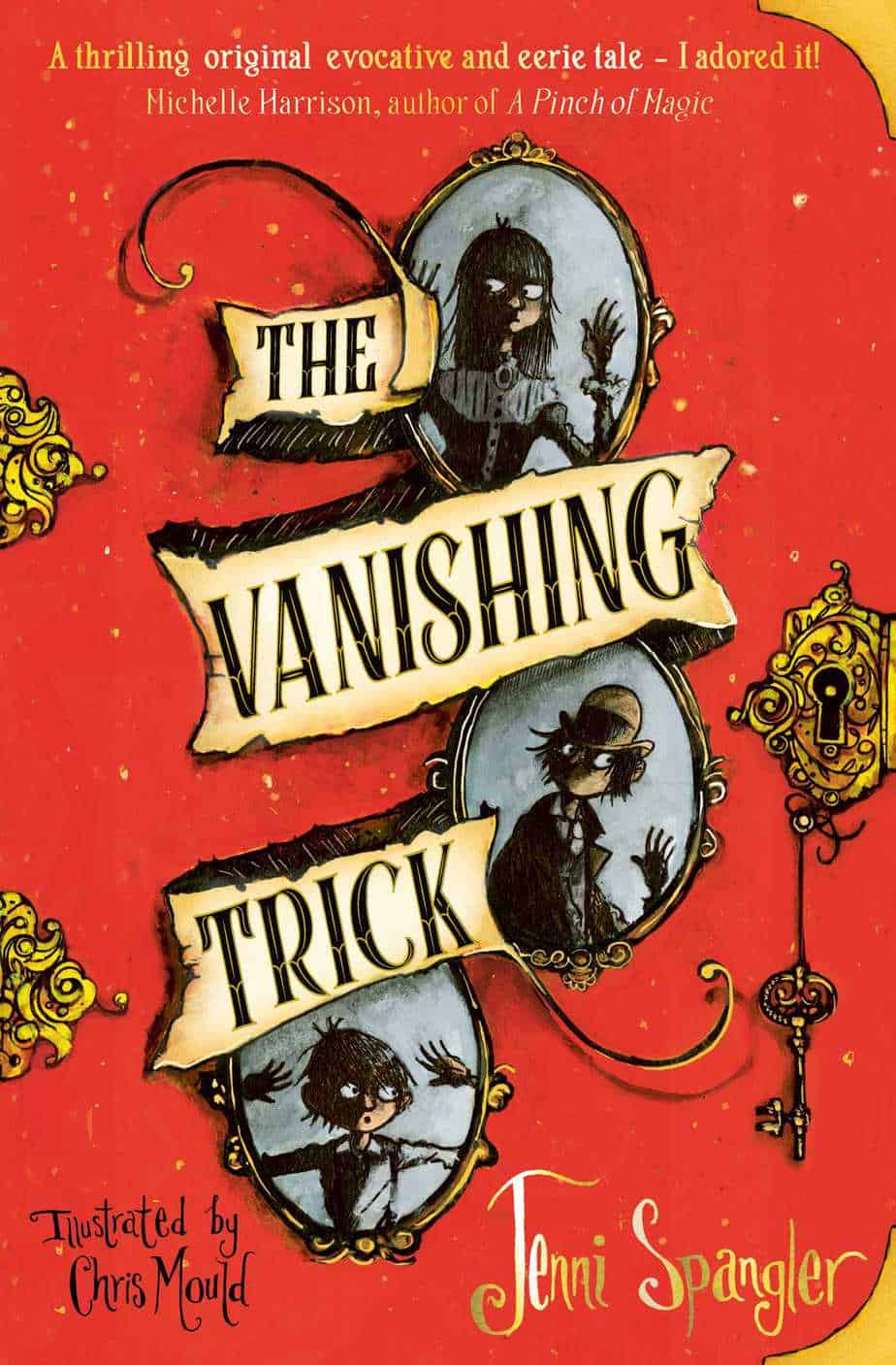

Step into a world of secrets, folklore and illusions, where nothing is as it seems and magic is at play…

Madame Augustina Pinchbeck, travels the country conjuring the spirits of dearly departed loved ones… for a price. Whilst her ability to contact ghosts is a game of smoke and mirrors, there is real magic behind her tricks too – if you know where to look.

Through a magical trade, she persuades children to part with precious objects, promising to use her powers to help them. But Pinchbeck is a deceiver, instead turning their items into enchanted Cabinets that bind the children to her and into which she can vanish and summon them at will.

When Pinchbeck captures orphan Leander, events are set into motion that see him and his new friends Charlotte and Felix, in a race against time to break Pinchbeck’s spell, before one of them vanishes forever…

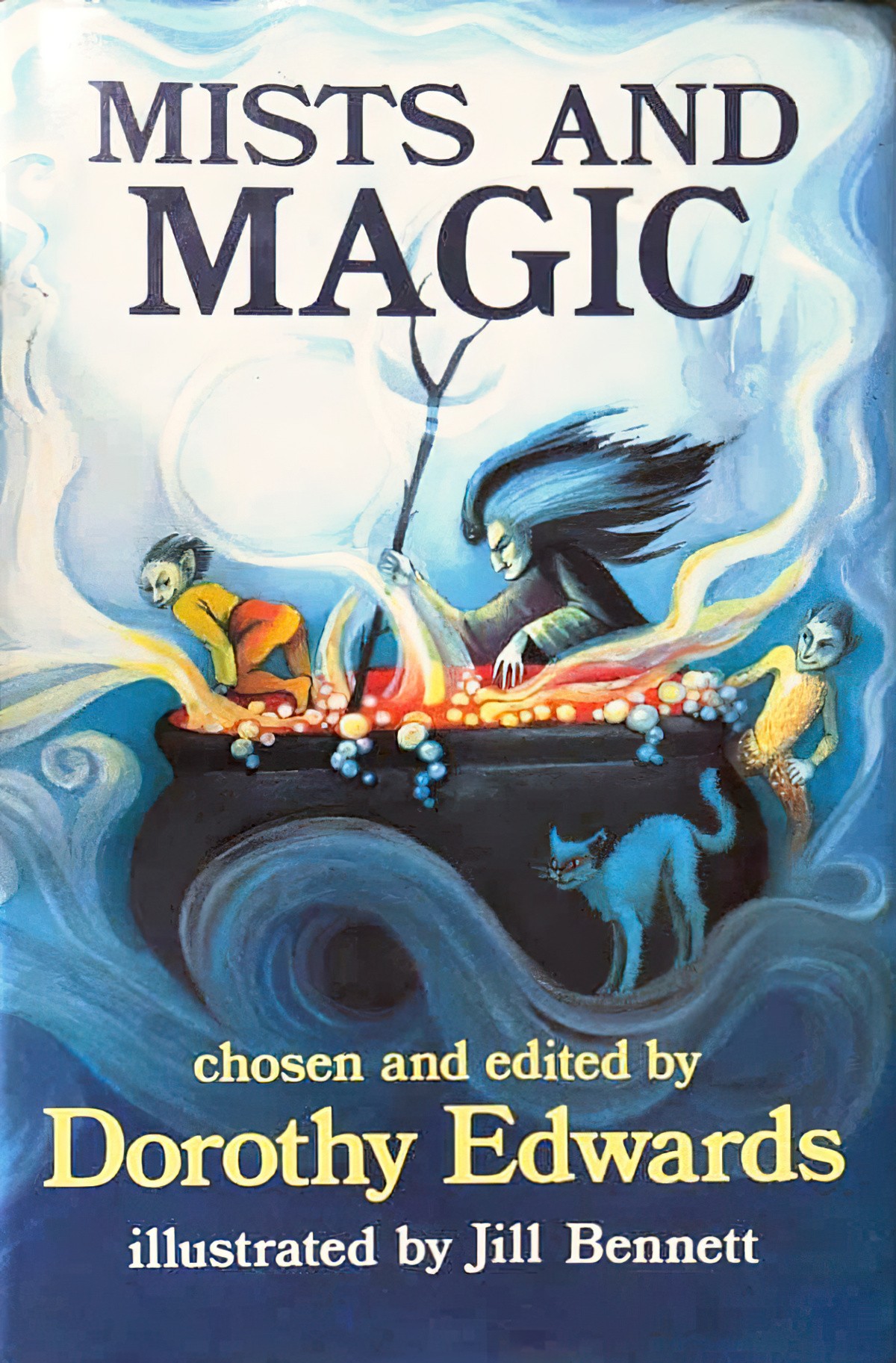

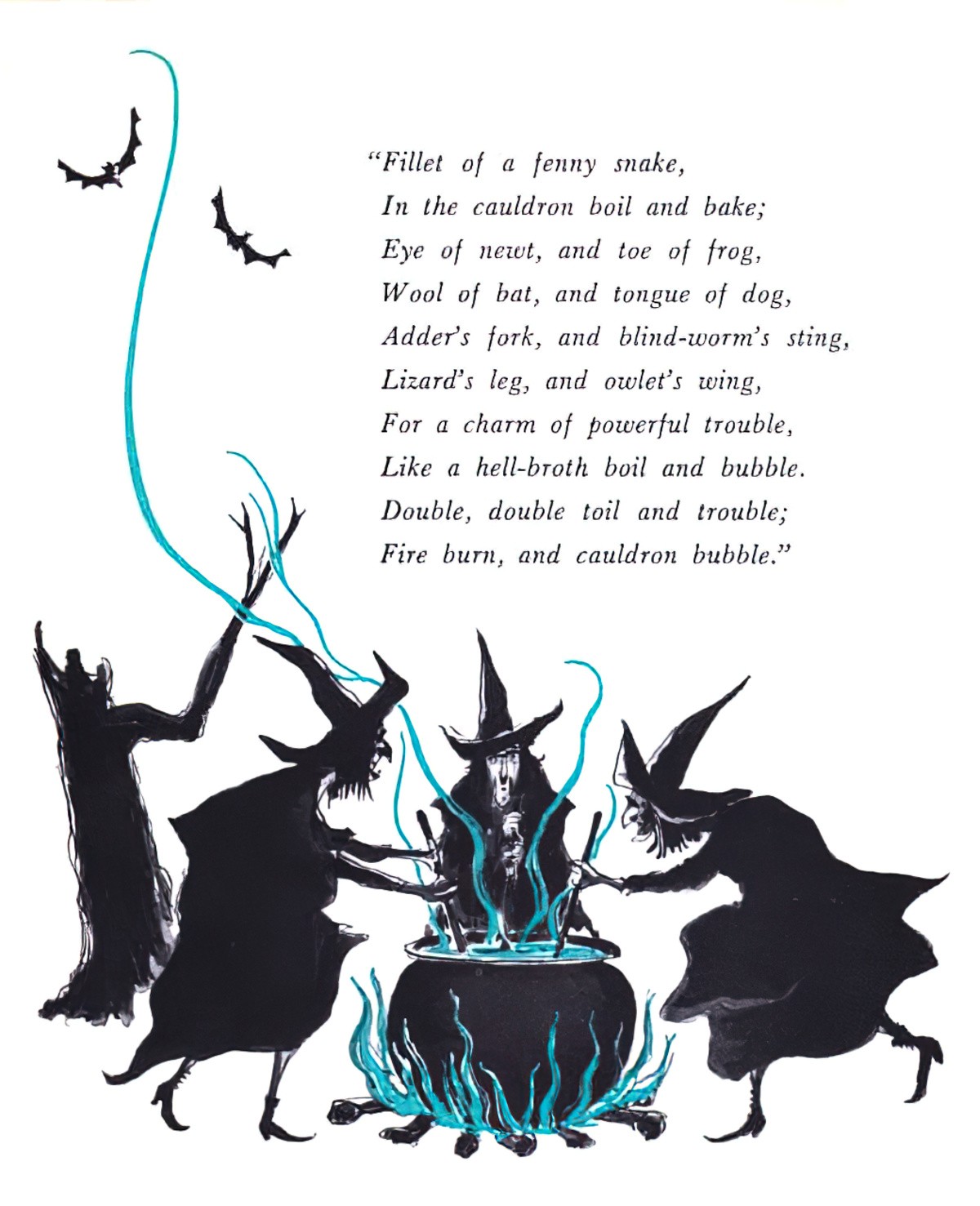

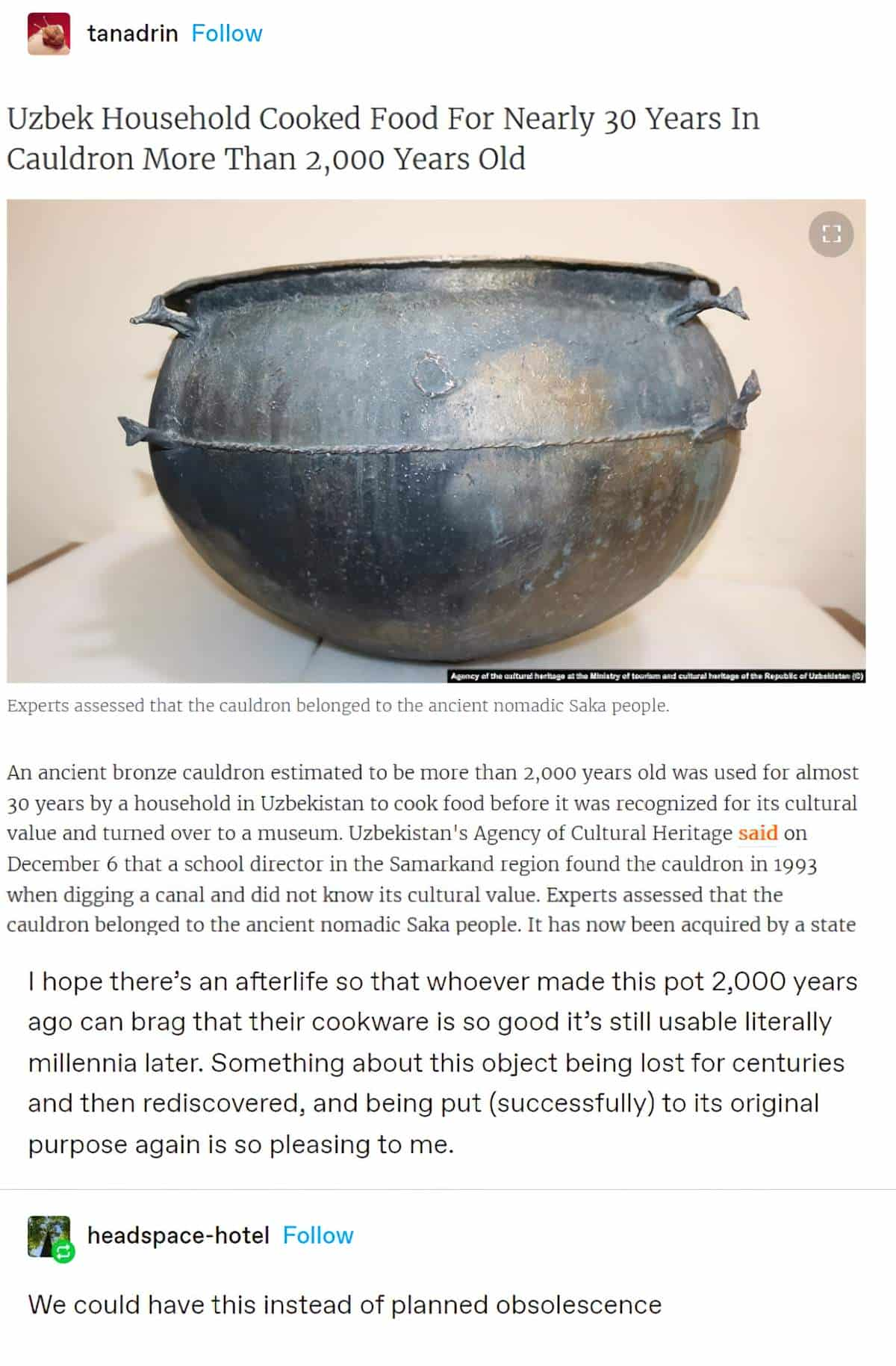

Cauldrons

In fiction, cauldrons have a special association with magic. Some such cauldrons are inherently magical, having some special power or another (an obvious one being the power to produce an endless supply of something you’d make in a more normal pot). Others are just used for magic (especially when Alchemy Is Magic), but apart from that, are just ordinary pots. They’re often black, and the contents are often inexplicably green, but both those things are optional.

TV Tropes

Sometimes the cauldron is called a kettle. Cauldrons and kettles come in various shapes and sizes. Cauldrons can be terrible or wonderful, oftentimes both.

According to witch mythology, an iron cauldron or kettle was used to prepare Sabbat feasts, magical brews and potions. Sometimes the fire is kindled in the cauldron itself. Some witches in fact use ordinary household pots — consecrated, of course.

In public imagination, the cauldron (your own cooking pot) was equally a tool you could use to kill a witch. By performing folk magic you could force a witch down your chimney, where she will fall into your cooking pot and be scalded to death. In order for this to work, people had to imagine a witch small enough to fall down a chimney, so it was necessary to believe that witches could transmogrify. This made them even more scary, because now you believed a witch could get in through any tiny crack.

The shape of the cauldron resembles the belly of a pregnant woman, and is therefore a symbol of fertility. Its circular shape symbolises never-ending life and regeneration.

Things are heated inside a cauldron, transforming from one thing into another, hence the cauldron also symbolises germination and transformation.

Traditional cauldrons have three legs, representing the triple aspect of the Great Goddess or the three fates. Any cauldron with three legs has strong associations with divination.

Cauldrons are strongly associated with cannibals, e.g. ogres. A cauldron of burning oil means punishment is coming, e.g. in earlier, more disturbing versions of Sleeping Beauty.

But in Celtic tradition, the cauldron symbolises abundance, cornucopia, resuscitation and inexhaustible sustenance. In these stories the dead are frequently thrown into the cauldron and crawl out alive the next day. For this meaning, we can look to a fairytale such as The Magic Porridge Pot (generally illustrated as a mini cauldron in picture books). The pot saves a community from famine but also wreaks havoc, in line with the good and evil duplicity of mythological cauldrons. Likewise in China, the cauldron is a receptacle for offerings. but also a container for torture and capital punishment.

Norse legend is a bit different. According to Nordic tradition, the roaring cauldron is the source of all rivers.

The Chalice

A chalice is a cup or grail generally used in rituals. The Catholic church makes use of a highly decorated chalice in ceremony. Pagans used a much simpler one.

The chalice itself symbolises water. Like the cauldron, the chalice is associated with femininity because of its shape, and because of its use as a vessel (women were and still are considered vessels for carrying other humans). Women are also linked to water because women are linked to the moon — menstrually — and the moon influences tides. We all begin life in the womb in water. Like most associations, it’s a double-edged sword for women. Water, like women, is essential to life. (Women, eh? Can’t live with em, can’t live without em.)

The Holy Grail

As mentioned above, in mystical, pre-Christian times there was a magical cauldron of the Celtic Gods that never emptied and kept everyone satisfied, as mentioned above. This legend is the O.G. of mythology leading to the Holy Grail — the cup that Christ was meant to have drank from at the Last Supper, or maybe it was the container that caught his blood during his crucifixion… who knows?

This sacred vessel went missing (or never existed in the first place), so today ‘the Holy Grail’ means something unfindable but highly treasured. There’s a subcategory of King Arthur tales called Holy Grail Legends, which have kept the rumours alive.

According to Jung, the psychoanalyst, the grail is an emblem of the spirit and symbolises “the inner wholeness for which men have always been searching”. The Philosopher’s Stone, from alchemy, fulfils the same symbolic function — the search for something elusive within oneself.

Header painting is by Leslie Hunter: Kitchen Utensils, c.1914–18.