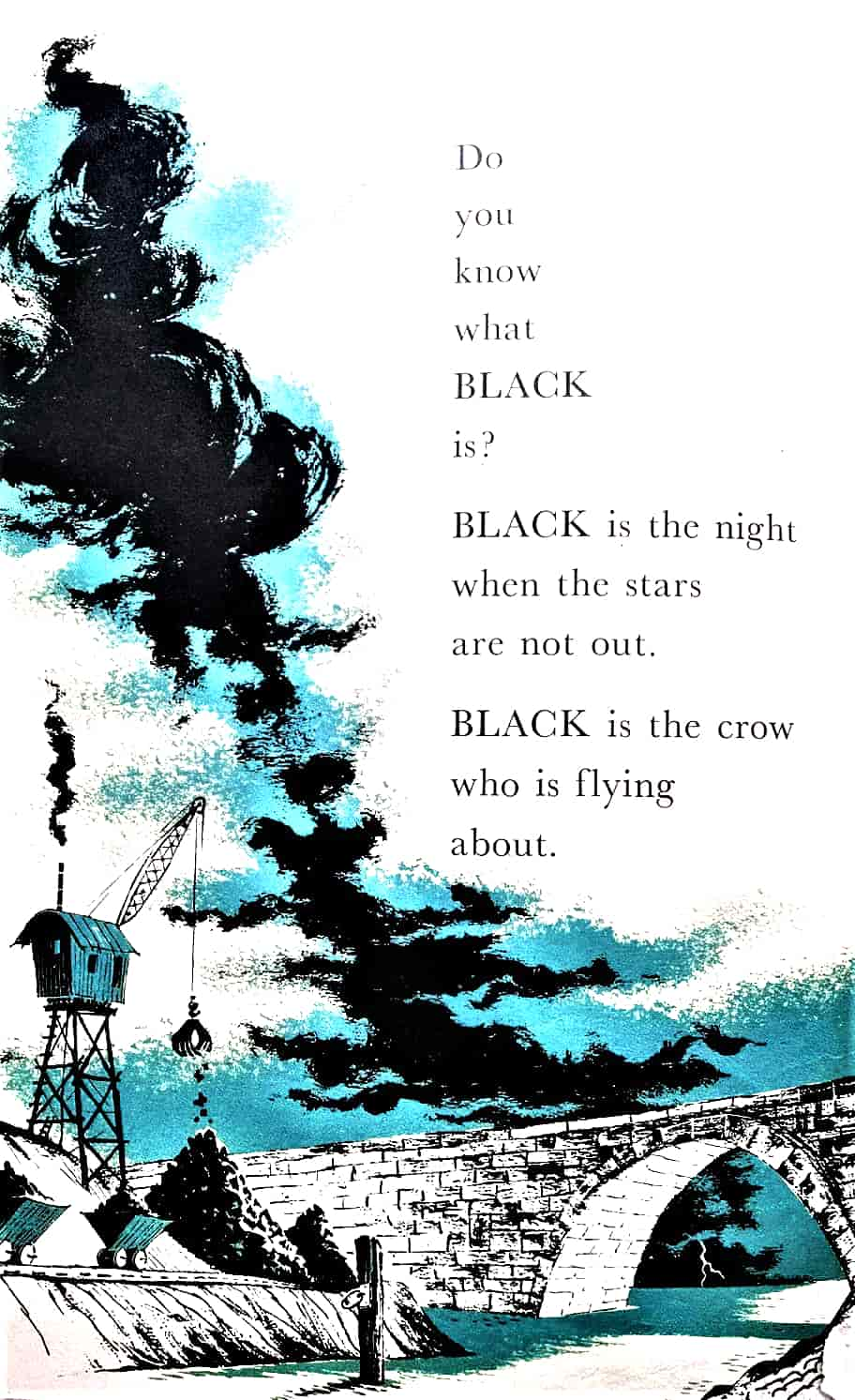

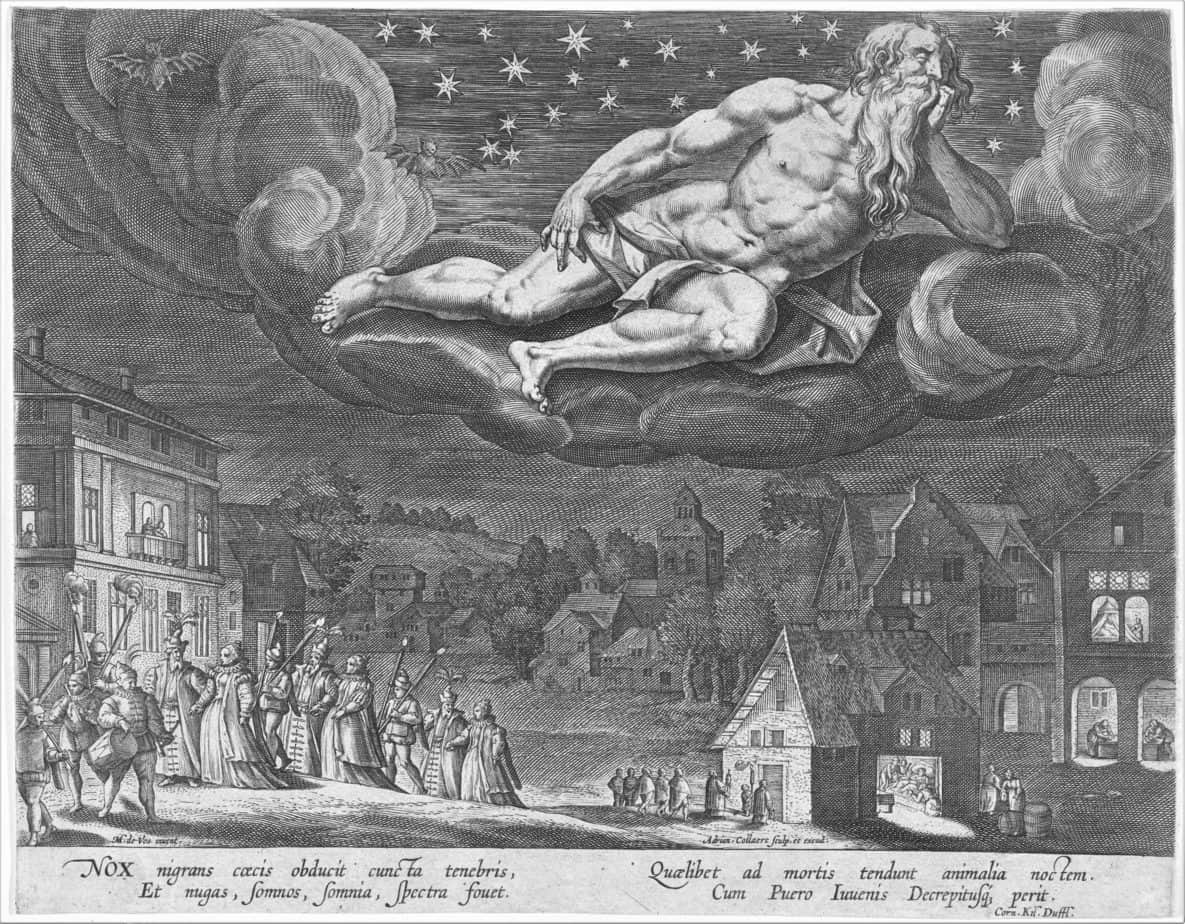

Across the globe, black has negative connotations. This is probably because night-time is black, and historically night-time is the scariest, most dangerous time for humans. Our eyes have evolved for daylight. That’s why I’m combining ‘night’ and ‘black’ when delving into symbolism.

Black is not technically a colour, rather an absence of colour. Artists are often advised against using black out of the tube. Instead we are to mix a dark hue from other colours. More interesting blacks are achieved if they are red black or blue black, say. This is debatable advice.

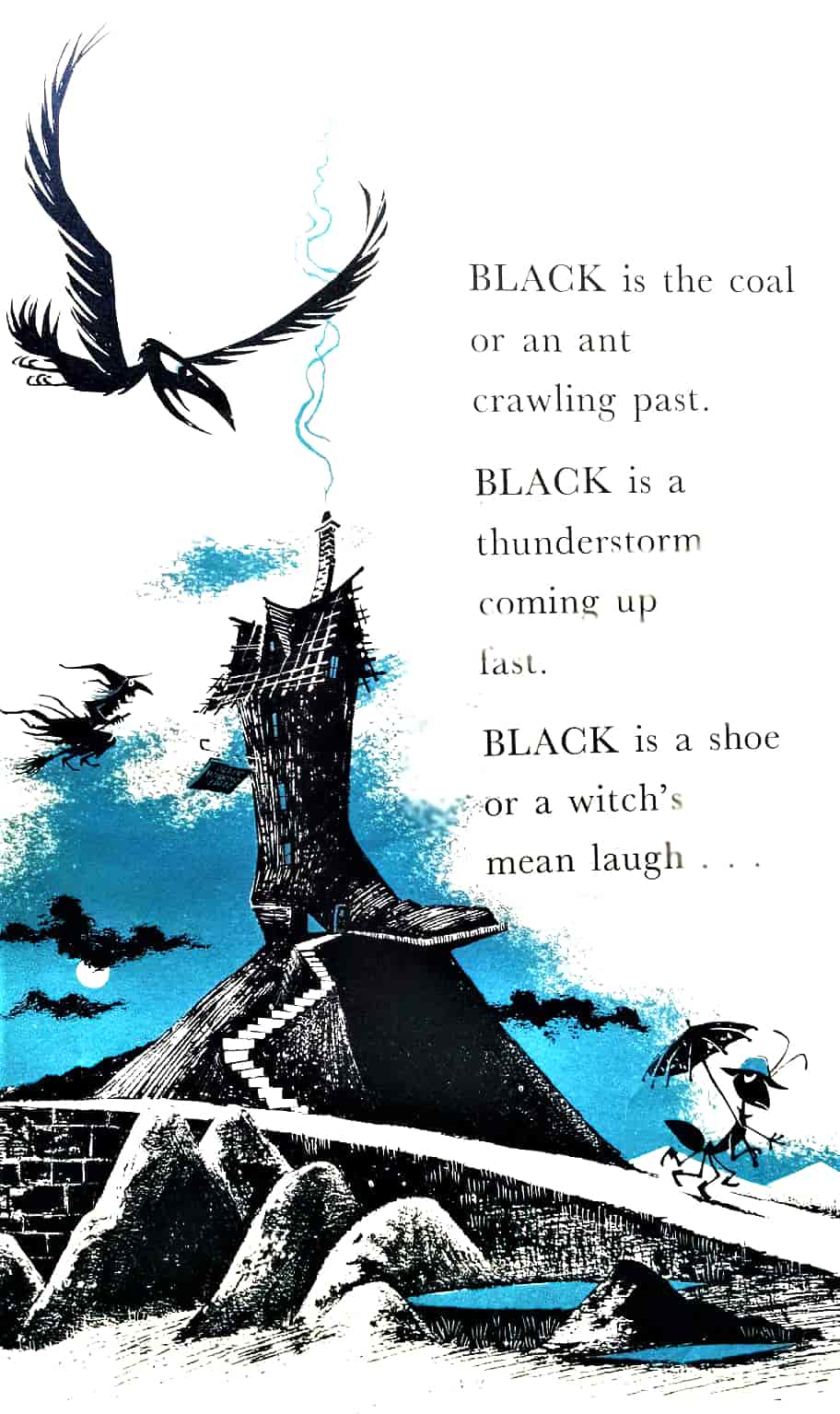

Other associations with darkness and black:

- evil and general badness

- mourning and funerals (especially in the West)

- anything taboo

- depression (e.g. Black Dog)

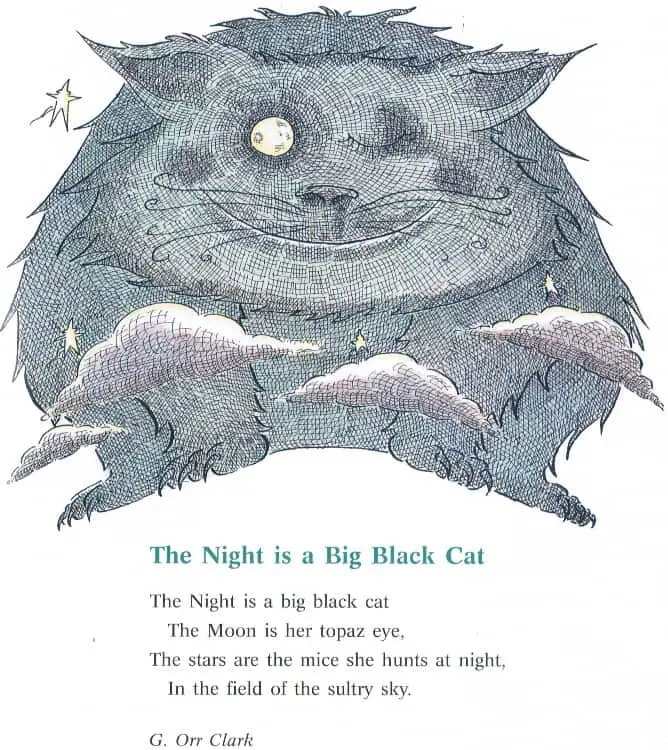

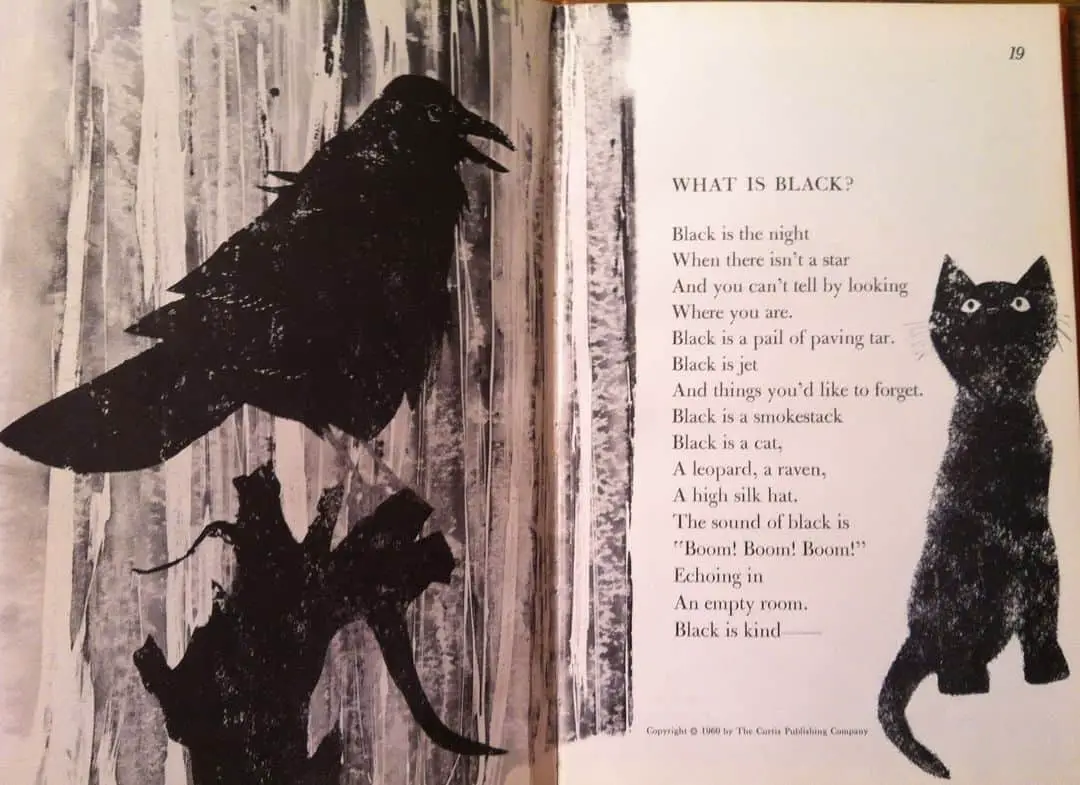

- witchcraft (e.g. black cats, black cloaks, cauldrons)

- goths

- secrets/cloaking/mystery

There are cultural variations on black. For example:

- In Japan, black is one of the four important colours. Black indicates wisdom, maturity and high accomplishment, hence black belts in martial arts. In Japan black is also the opposite of the colour purple, associated with the armoury of samurai, and in ancient times geisha used black to colour their teeth.

- The Cathars were a dualist medieval religious sect of Southern France. Like Japan, the Cathars also used black to mean perfection and purity. (Today purity is most often symbolised using white.)

- Though black is generally considered bad, black cats are lucky in the United Kingdom and in many parts of the world. Black contains layers of flipped symbolism.

The treatment of darkness also differs generally across time. Thomas Hardy used the motif of darkness differently from writers of the Victorian tradition. Victorian writers treat darkness as something other. For them, dark is dangerous and mysterious. But Hardy’s characters are perfectly at home in the dark.

The night in all its fullness met her flatly on the threshold, like the very brink of an absolute void, or the ante-mundane Ginnung-Gap believed in by her Teuton forefathers. For her eyes were fresh from the blaze, and here there was no street lamp or lantern to form a kindly transition between the inner glare and the outer dark.

The Woodlanders, Thomas Hardy, Chapter 3

Hardy’s work evinces a writer who grew up without electric lighting. His characters know how to get around in the dark by utilising other senses.

[a] lingering wind brought to her ear the creaking sound of two overcrowded branches, which were rubbing each other into wounds, and other vocalized sorrows of the trees.

The Woodlanders, Thomas Hardy, Chapter 3

Hardy also describes how characters look up to the sky in order to orient themselves in darkness. He writes about the play of light and shadows.

Associations With Night-time

Night falls. Or has fallen. Why is it that night falls, instead of rising, like the dawn?… Maybe night falls because it’s heavy, a thick curtain pulled up over the eyes. Wool blanket.

Margaret Atwood

I often dreamed of watching without being seen. Of spying. Of being the perfect observer. Like that camera obscura I once made out of a shoebox. It photographed for me a part of the world through a black closed space with a microscopic pupil through which light sneaks inside. I was training. The best place for this kind of training is Holland, where people, convinced of their utter innocence, do not use curtains. After dusk the windows turn into little stages on which actors act out their evenings. Sequences of images bathed in yellow, warm light are the individual acts of the same production titled Life.

Olga Tokarczuk, Flights

If you’re coming home after 6pm then you need to enter your house backwards or else an evil spirit will follow you inside.

@HauntedHistory2

- In English we say night ‘falls’ but actually it rises, emerging first in the valleys.

- Fading rays are known as ‘sun suckers’.

- Eventide is an archaic term — Irish people have a saying that bushes and men look alike. Italians say hounds look like wolves.

- Night feels palpable, like some sort of dark mist. The Old Testament talks about darkness that befell Pharoah’s Egypt.

- Night Vapours: Noxious fumes are widely thought to descend from the sky. “Night fogges” and “noysom vapours”

- Shakespeare — “the daylight sick”. “Make haste, the vaporous night approaches.”

- Noctivagator was a Latin term used to refer to people who walked around at night causing trouble in the Middle Ages. It was later replaced by nightwalker in England in around 1500.

- Linkboys were orphans and urchins, paid to carry lights for pedestrians. They were not well trusted, sometimes leading customers straight to pick-pockets.

As nature tires of human destruction, two sisters must face a changing environment that stands between them and survival.

When Quinn and Riley set out on a family vacation with their parents, the trip ends before it begins. Mother Nature interferes with their plans, setting off a sequence of events that thrusts the teens into a hostile landscape.

Stranded, with limited supplies, struggling to figure out who they can trust along the way, they must determine how to survive nature’s evolving fury.

Ancient Times Of Day

Before the industrial era nightfall was known as ‘shutting in’. Watchdogs have been let out by nightfall, so it is time to lock yourself in for the night.

- Gloaming (twilight, dusk)

- Cock-shut/cockshut — twilight

- Crow-time — evening

- Daylight’s gate — The period of the evening when daylight fades; twilight. From the early 17th century.

- Owl-leet — perhaps Lancashire dialect for ‘owl light’, when owls come out

Darkness and Fear

All humans seem to fear the dark, probably an instinctive thing after many generations of learning to fear things which emerge in the dark. But not all cultures fear dark equally. Fear levels depend on the cultural narratives around night-time.

We don’t just fear the dark because we can’t see through it. We fear it because we can’t be recognised as ourselves. This is especially scary for children, who fear their parents may not recognise them in the darkness. In ancient stories, the coal man who covers children’s faces with coal is a terrifying bogeyman.

Deinos melas means ‘scary black’ and describes the ghost of one of Odysseus’ sailors.

Also, cultures change across time. Modern cultures fear dark less than earlier cultures — in this modern era there is no true darkness in populated areas anyway.

People weren’t really afraid of the dark until the END of the middle ages. Before then the dark was considered a peaceful time. Then we got vampires, werewolves, witches and all sorts of horrible night creatures and people actually believed these things existed, outside a few analytic mindsets. A great number of people sat on the fence, agnostic about the existence of such things. Others were absolutely terrified by their own supernatural beliefs, sometimes to the detriment of others:

On a winter night in 1725, a drunken man stumbled into a London well, only to die from his injuries after a neighbour ignored his creeds for help, fearing instead a demon.

At Day’s Close: Night in times past by A. Roger Ekirch

Since people were so scared of the night, this was excellent for pickpockets and thieves, who were able to utilise that and almost always used the cover of darkness to commit their crimes. It even became a separate crime. Housebreakers worked in the daytime, burglars by night between 1660 and 1800.

Curtains

Curtains weren’t a thing until the 18th century. When people first got them, neighbours assumed the worst regarding what was going on behind them. At that time everyone knew everyone else’s business. That’s not to say people hadn’t wanted privacy. The reason privacy became paramount then and not at any earlier time is because that’s when people started to accumulate personal possessions of their own. The words ‘privacy’ and ‘private’ didn’t exist in English until the 1400s. But by the time of Shakespeare these words were known and used by everyone.

Devil’s Work

In earlier eras across Europe, there were laws about what jobs were allowed to be done at night. Basically, working at night was considered very suspicious because night was for the devil’s work. People were even beaten to death for working after dark. However, you were allowed to work if it was in service to a noble family. You were also allowed to work if you were preparing for a carnival or fair. Depending on the culture, exemptions were made for overnight working. In Sweden and Amsterdam for instance workers were allowed to make beer overnight because beer was very important.

Although work was generally not allowed at night, ‘day-labour’ really did mean from dawn until dusk, until modern labour laws came in. Just as well for the superstitions, I suppose, or the working class would never have been afforded sleep.

According to some belief systems, prayer, piety and church attendance can protect you from sin (darkness) because your body emulates light. Take the following from a Pentecostal churchgoer in Papua New Guinea:

When witches confess, they say things like: “When we encounter people who follow Jesus, when we would like to get close to them, there is a light! A strong light! It reflects against our vision, and we can’t get close to them.”

Becoming Witches

From the brothels and gin-shops of Covent Garden to the elegant townhouses of Mayfair, Laura Shepherd-Robinson’s Daughters of Night follows Caroline Corsham, as she seeks justice for a murdered woman whom London society would rather forget . . .

Lucia’s fingers found her own. She gazed at Caro as if from a distance. Her lips parted, her words a whisper: ‘He knows.’

London, 1782. Desperate for her politician husband to return home from France, Caroline ‘Caro’ Corsham is already in a state of anxiety when she finds a well-dressed woman mortally wounded in the bowers of the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens. The Bow Street constables are swift to act, until they discover that the deceased woman was a highly-paid prostitute, at which point they cease to care entirely. But Caro has motives of her own for wanting to see justice done, and so sets out to solve the crime herself. Enlisting the help of thieftaker, Peregrine Child, their inquiry delves into the hidden corners of Georgian society, a world of artifice, deception and secret lives.

But with many gentlemen refusing to speak about their dealings with the dead woman, and Caro’s own reputation under threat, finding the killer will be harder, and more treacherous than she can know . . .

See Also

Darkness triggers a chain of interrelated processes, including a cognitive processing style, which is beneficial to creativity…But they also gave [subjects] four logic problems that required a great deal of analytical thinking. This time the researchers found that while creativity thrived in the dark, careful reasoning flourished in the light.

Why Creativity Thrives In The Dark, Fast Company

- Illustrating the dark

- The Dark by Lemony Snicket and Jon Klassen

- The rule of oversized moons in picture books

Header painting: Past and Present, No. 2 1858 Augustus Leopold Egg 1816-1863