The cloak is the garment of Kings, and the King is a symbolic archetype. Fathers and Kings are basically the same archetype in traditional stories. (Fathers are the kings of the home.)

Andrew Lloyd-Weber’s musical Joseph and the Techni-colour Dreamcoat is based on this Biblical story. Artists have taken the concept of the colourful coat and taken it to its extreme. What’s the most colourful coat you can possibly imagine? Why, it’s psychedelic, of course.

COATS IN FOLKTALES

The following is from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman, 1966. Read through these story summaries and you’ll get a good idea of how coats have been used throughout history. Can you see patterns?

- Thrush‘s hospitality to peacock rewarded by being given motley coat of feathers.

- Birds who aspire to blackbird’s coat punished.

- Serpent steals from God‘s coat a stick for his back.

- Bird council assigns coats to different birds.

- Fish with coat of wool.

- Taboo: looking through the upturned sleeve of a fur coat. One sees ghosts.

- Swan Maiden. A swan transforms herself at will into a maiden. She resumes her swan form by putting on her swan coat.

- Magic coat protects against attack.

- Christ‘s coat of mercy protects Pilate from punishment.

- Magic coat kills.

- Person meets girl at dance, dances with her, often drinks with her, takes her horne. He goes to see her next day, finds she has been dead several years. Often a coat he has lent her is found on her grave.

- Fairies wear patched coats.

- Wife throws husband’s waistcoat over herself and child when fairies attempt to make exchange.

- Persons who are led astray by fairies break spell by reversing an article of clothing: coat, glove, etc.

- Fairy spell averted by turning coat. This is supposed to reverse the spell.

- Coat pockets of water-spirits are dripping with water.

- Dwarfs wear red coats.

- Giants wear long coats with lamps under them.

- Wooden coat.

- Coat so light it can be concealed in closed palms of hand.

- Witch removes overcoat of man, leaves it in tree one hundred yards away.

- Devil wears a bright green coat.

- Devil repays a kindness: returns coat lent him and brings the one who had shown him kindness back home when imprisoned.

- Test: guessing nature of certain skin–louse-skin. Louse (flea) is fattened and its skin made into coat (drum, etc.)

- Man helps traveler and makes riddling remarks. Gives him food, shares his coat in rain, and carries him over stream. Reproaches him with traveling without mother, house, or bridge (nourishment, shelter, or horse).

- ”May God spare you from an evil man or evil woman.“ To teach a friend the wisdom of this greeting a man borrows money and then his creditor‘s coat from him. In court the lender is discredited.

- (Content note: anti-Semitism) Witness claims the borrowed coat: discredited. Trickster summoned to court on Jew’s complaint refuses to go unless he has a new coat: Jew lends him his. In court the trickster says that the Jew is a liar: “He will even claim that I am wearing his coat.” The Jew does so and no one believes him.

- Receiver of stolen goods. A tailor makes a Jew a coat of stolen goods. Accused of theft, he says that the Jew has the cloth.

- Servants would not have left the coats. Merchants complain to nobleman that his servants have robbed them of money. Nobleman asks whether merchants had on those good coats when the robbery took place. When told yes, he said that the robbers were not his servants, for they would never have left good coats.

- How much cloth would it take to make God‘s coat? Just as much as for me, for what you have done for a poor person in my name you have done for me.

- The burden of two asses. A king and his son hunting on a hot day put their fur coats on the fool‘s back. King: ”You have an ass’s load on you.“ Fool: ”Rather the burdens of two asses.“

- They gave it away themselves. A wandering actor rewarded by a city with a coat of their color gambles it away. When upbraided about giving away their present he replies that they hadn’t wanted to keep it themselves.

- Dungbeetle thought to be bee. “I know you well enough, you have put on a blue coat.”

- The ass deprived of his saddle. A man’s coat is stolen when he leaves his ass for a moment. He takes the saddle off the ass and says that he will give it back if the ass will return the coat.

- A number of parishoners fight against installing stove in church. (They enjoy warming up at the tavern before church and at special intermission.) On the first Sunday after the stove is installed (a bitterly cold day) the members lay aside their coats; one woman faints from heat, has to be taken to tavern to be revived. It is discovered that there is no fire in the stove.

- Man believes he will die when he gets a scarlet thread on his coat.

- The moving church tower. To see whether the church is moving someone lays down his coat in front of it. It is stolen. They think that the church has passed over it.

- Think thrice before you speak. The youth obeys literally the precept even when he sees the master‘s coat on fire.

- Watchdog enticed away. Trickster brings rabbit under his coat. When the king‘s watchdog gives chase the trickster enters and robs.

- Theft by use of coat of invisibility.

- Frightened robber leaves his coat behind.

- Umpire awards his own stolen coat to thief.

- Thief tricked into robbing himself. He has placed a coat on the goods to be stolen. His associate changes the place of the coat.

- Compassionate executioner: bloody coat. A servant charged with killing the hero smears the latter‘s coat with the blood of an animal as proof of the execution and lets the hero escape.

- Seduction by wearing coat of invisibility.

- The marked coat in the wife‘s room. A procuress obtains a woman for her client by leaving a marked coat in her room. The husband drives the wife away and she joins her lover. The procuress then goes to the husband and alleges that she lost a coat with certain marks. The husband is deceived and takes the wife back.

- Wife’s admirer gives her an expensive fur; she devises stratagem to enable her to keep it. She locks it in a key locker in railway station, tells her husband that she has found the key, and asks him to find out whether there iS anything of value in the locker. He finds the coat, takes it to his office where his secretary thinks the coat is for her. He gives her the coat, takes an old battered umbrella (from a pawnshop) home to his wife.

- Contest of wind and sun. Sun by warmth causes traveler to remove coat, while wind by violent blowing causes him to pull it closer around him.

- Person goes to cemetery on a dare: he is to plant a stake in a grave or stick a knife or fork or sword or nail into a grave (or coffin). The knife is driven through the person’s loose cuff, or the nail is driven through part of the sleeve, or the stake is driven through the person’s long coat tail.

- Grave robber thrusts shovel through bottom of long coat, dies of fright.

- Money found in the dead beggar’s coat.

- Man scolds his ass and frightens robber away. While the man is absent from his ass the robber steals the man‘s coat. The ass brays and the man scolds him. The robber thinking he is discovered flees and leaves the coat.

- Knight covers foal with his coat to protect it from storm.

- Death as punishment for dropping on emperor’s coat.

- Princess evades unwelcome lover by putting on foul-smelling skin-coat.

- Holy man has his own mass. (Cf. F1011.1, V29.3.) When upbraided for not coming to mass, he hangs his coat on a sunbeam.

- Saint exchanges coat with beggar: gold sleeves miraculously appear.

- Philanthropist will give his spurs if someone will drive his horse for him. He has given away his coat, etc. to beggars. One finally asks for his spurs.

- Harlot weeps when her impoverished lover leaves her to think that she has left him his coat.

- Oversight of the thievish tailor. Sews the stolen piece of cloth on the outside of his coat, thinking that it is on the inside.

- Thievish tailor cuts a piece of his own coat.

- Indian watches trial of another Indian. Points to state coat of arms, asks judge to identify one of the figures: “What him call?” — “Liberty.” Points to another figure: “What him call?” — “Justice.” — “Where him live now?”.

- Sermon about the rich man. A boy rides with a rich man. Goes into church and leaves his coat lying on the sled. When the parson preaches about the rich man who went to hell, the boy calls out, “Then he took my coat along!”

- Tall man warns men when to put on raincoats. They have time to put them on before rain reaches them.

- Remarkable high jumper put on overcoat before jumping because of cold in high altitudes he attains.

- General Grant plowing canal plows through stump which closes on his coattails. He turns oxen around, snips off coattails with plow, then plows out the stump.

- Fish are so eager to be caught that man has to bait his hook under his coat.

- Deer follows man; its breath freezes all the way from deer’s nose to man’ s coat and deer strangles.

- Suit shrinks in series of rains. In first rain trouser legs come to knees, sleeves come to elbows, vest halfway to armpits. In second rain trousers become trunks, the coat and vest disappear altogether. By the time the man gets home he is naked.

- Horse runs so fast that only tail of man’s raincoat and the rear end of the horse get wet.

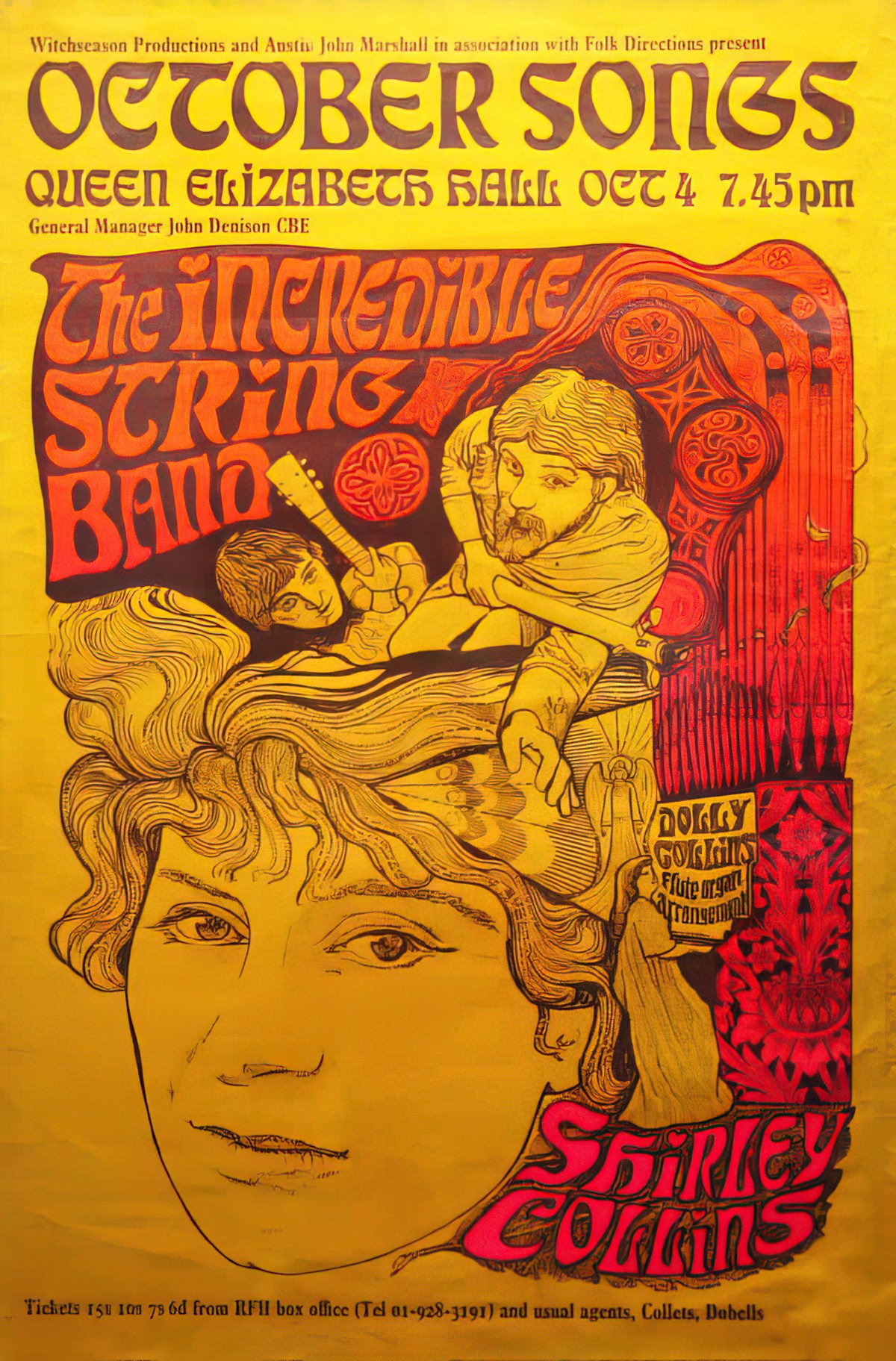

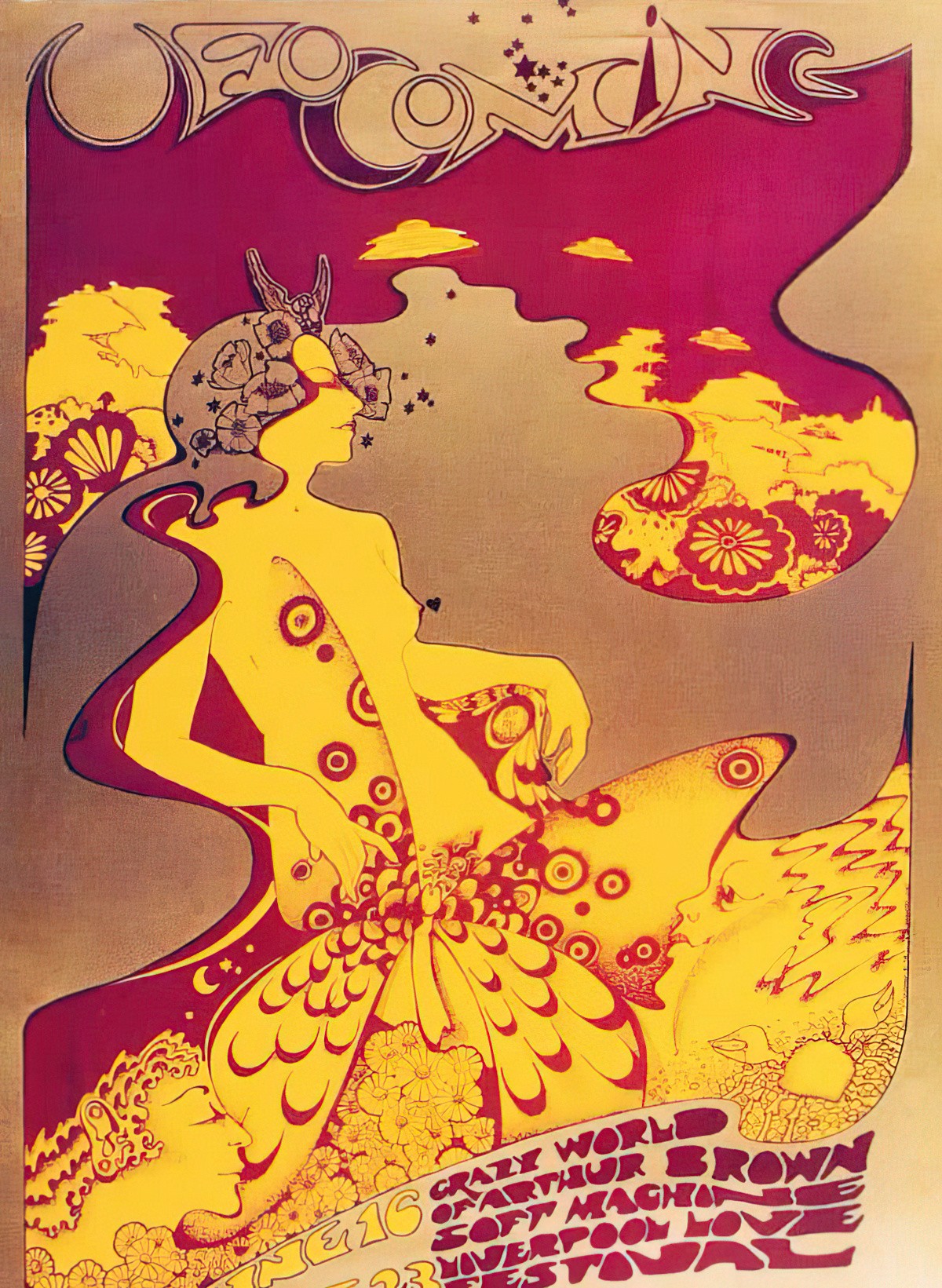

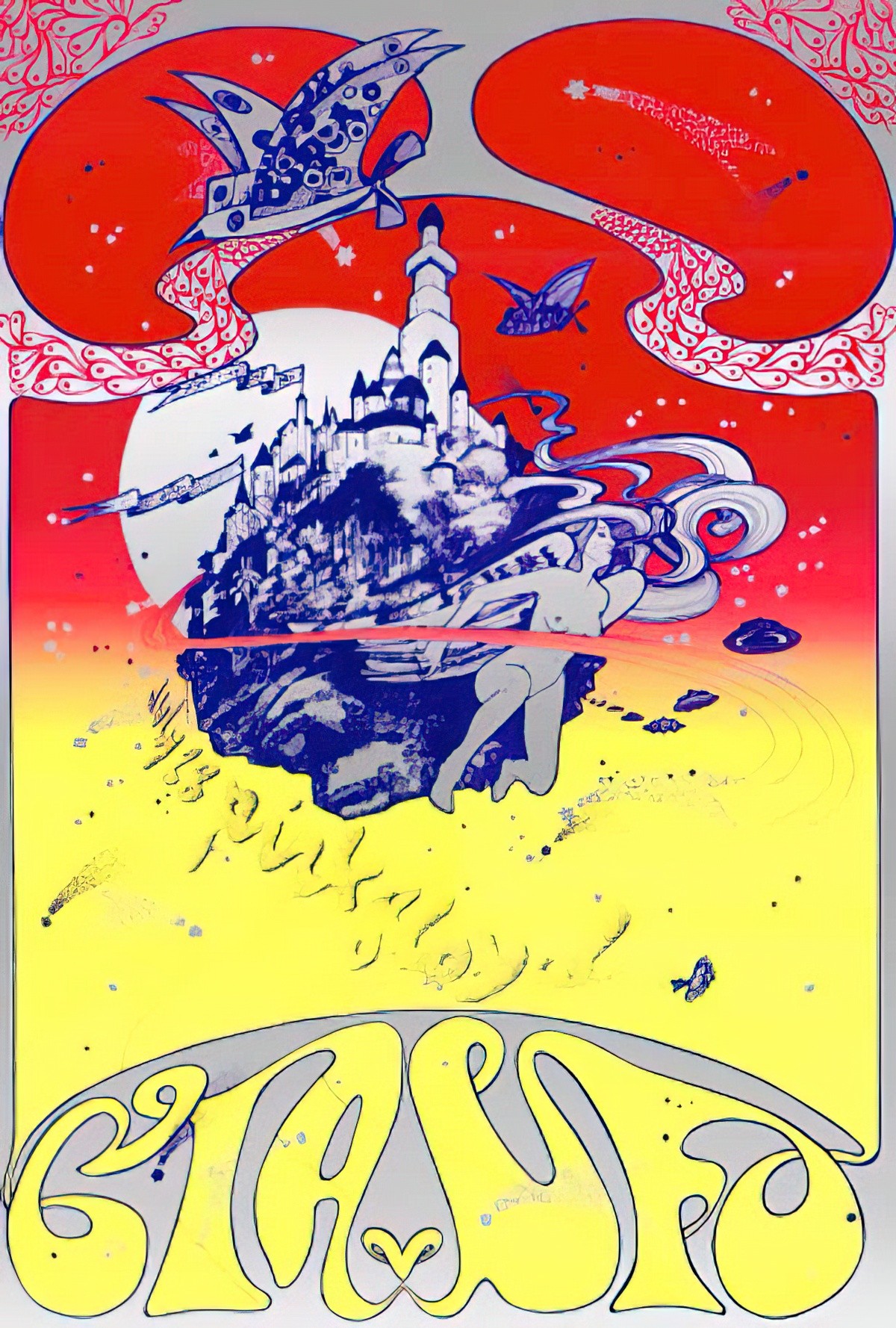

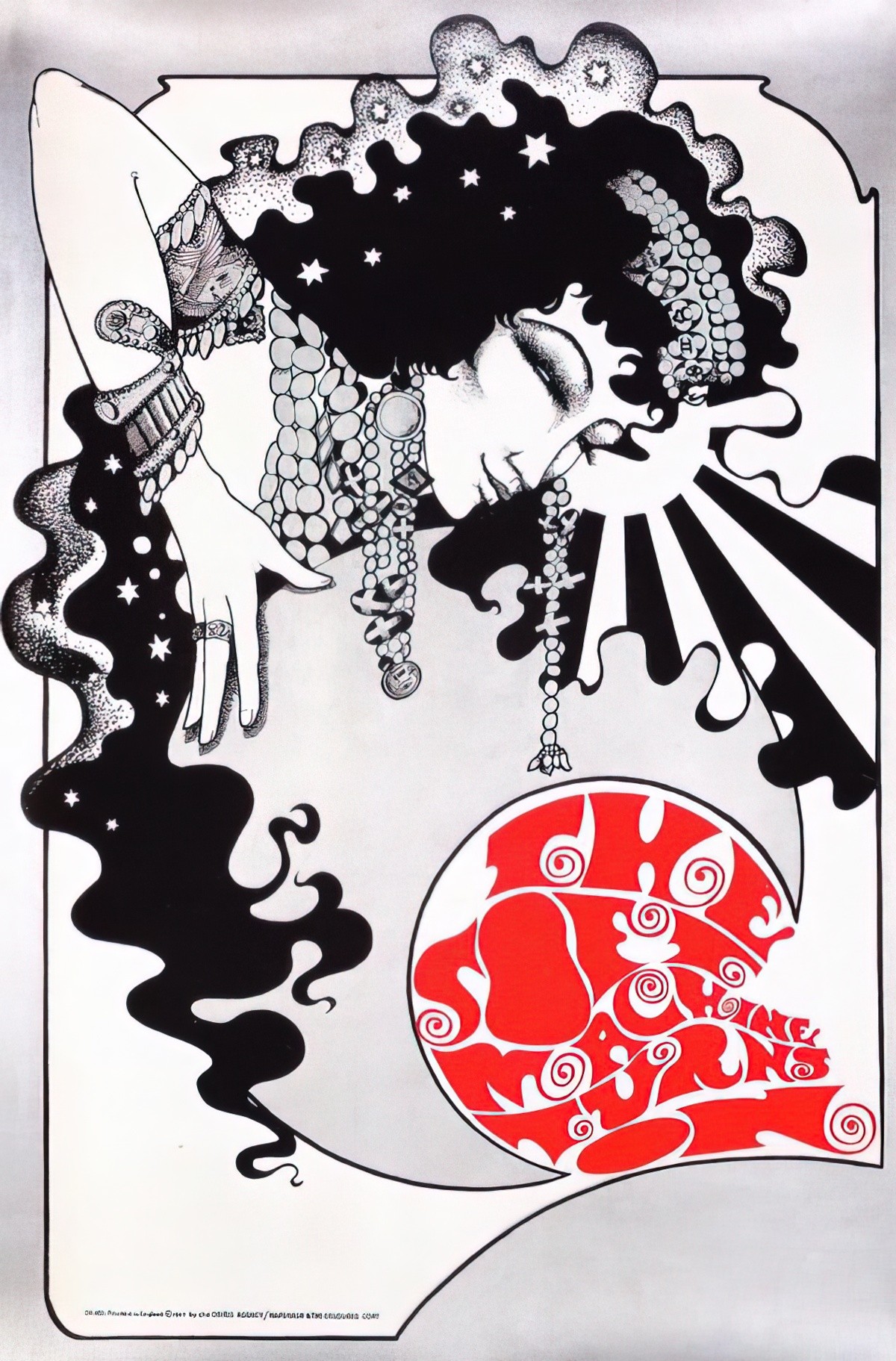

HAPSHASH AND THE COLOURED COAT

Hapshash and the Coloured Coat was an influential British graphic design and avant-garde musical partnership in the late 1960s, consisting of Michael English and Nigel Waymouth. It produced popular psychedelic posters, and two albums of underground music

Wikipedia entry for Hapshash and the Coloured Coat

The Coat Of Many Colours

The O.G. impressive coat comes from the Bible. Was it really highly coloured? Almost certainly not, by today’s standards.

In the book of Genesis, Joseph owned a coat that had been gifted to him by his father, Jacob. Joseph was Jacob’s favourite child. Translators debate the nature of this coat. It might’ve had many colours, or it may have been a long robe with sleeves. It may have been richly ornamented. In any case, safe to say this coat marked Joseph out as special, and was not the sort of thing you’d wear to work. Like all impractical clothing, this indicated that Joseph was a bit too special to work.

The father favoured Joseph because Joseph’s mother Rachel was the love of his life. All the subesequent brothers came from either Rachel’s younger sister Leah, or from handmaidens.

Jacob was a pretty shitty, divisive parent, to be fair. He got Joseph onside by telling him to spy on his brothers and report back to him of their wrongdoing.

So, Joseph was plucked off from the rest of his siblings by his own father. It’s not always great to be the favourite. He clearly knew he was the handpicked son, and that his job in life was to be up head of the family after Jacob died. To persuade his half-brothers that he was the chosen one, Joseph told them he’d had two prophetic dreams, in which his brothers all bowed down to him. Way to solve any power struggle, right? “Nah, you shuddup. I had a dream, and I was boss!”

The lesser-loved brothers weren’t too impressed with Joseph.

By the time Joseph was 17, they’d had a real gutsful, and plotted together to kill him. But Reuben wasn’t into murder, so persuaded the other brothers to throw Joseph into a pit. Reuben would come back and rescue Joseph from the pit later. That should give him a bit of a scare.

But without Reuben, the murderous brothers planned to sell Joseph. They could get 20 pieces of silver by selling him to some people passing through. So that’s what they did.

What to tell Dad, though? In a plot used later by the spinners of fairytales (Snow White springs to mind), Joseph’s half-brothers, minus Reuben, stripped him of his special coat, dipped it in goat’s blood (poor goat) and told their father that Joseph had been mauled to death by wild animals. Only his blood-soaked coat was left of him.

Ever since then, storytellers have been using coats in two main ways:

- Wear a coat and you’re special

- Wear a fancy coat and that still don’t mean your sh*t don’t stink

The Majestic Coat Inverted

Cloaks worn by powerful people are not always majestic.

The Khirka is a specific type of cloak worn by the Sufi mystic. The word ‘khirka’ originally meant a scrap of torn material. But it has an unworldly nature, originally coloured blue to symbolise a vow of poverty. (Christians use brown and gray for the same symbolic purpose, which is why monks dress in brown or gray.)

In order to earn a khirka, a Sufi has to undertake three years of training to show that he’s worthy for initiation. He has to understand the three levels of the mystic life: Truth, the Law and the Path.

“The Knight Of The Ill-Shapen Coat” is a heroic Arthurian legend. The youth in this story wears a golden coat but it doesn’t fit him at all, so it’s clearly not his. He asks King Arthur if he can prove himself as a knight. If he does well, this will apparently prove that he deserves the respect of someone who really does own their own, well-fitted golden coat. The underlying assumption here, taken for granted by the reader: In general you can tell a great man because he’ll be wearing a fancy coat.

The Pied Piper’s cloak is a coat made out of scraps of material. The ‘pied’ (multicoloured) nature of it tells the reader that he is too poor to afford an impressive coat, and instead has to make do with fashioning something out of scraps. His coat marks him out as a scavenger, and this is partly why the councillors completely underestimate him as a threat. They wrongly assume that if this guy can’t even afford his own proper coat, he can’t be very good at coming after money. To be honest, it is a bit of a mystery why the Pied Piper hasn’t managed to find himself a proper coat until now. I deduce he just really liked the pied coat, or it suited him well to be underestimated, maybe because he was a psychopath who enjoyed seeking retributive justice on those who had wronged him, acting as a Medieval Dexter.

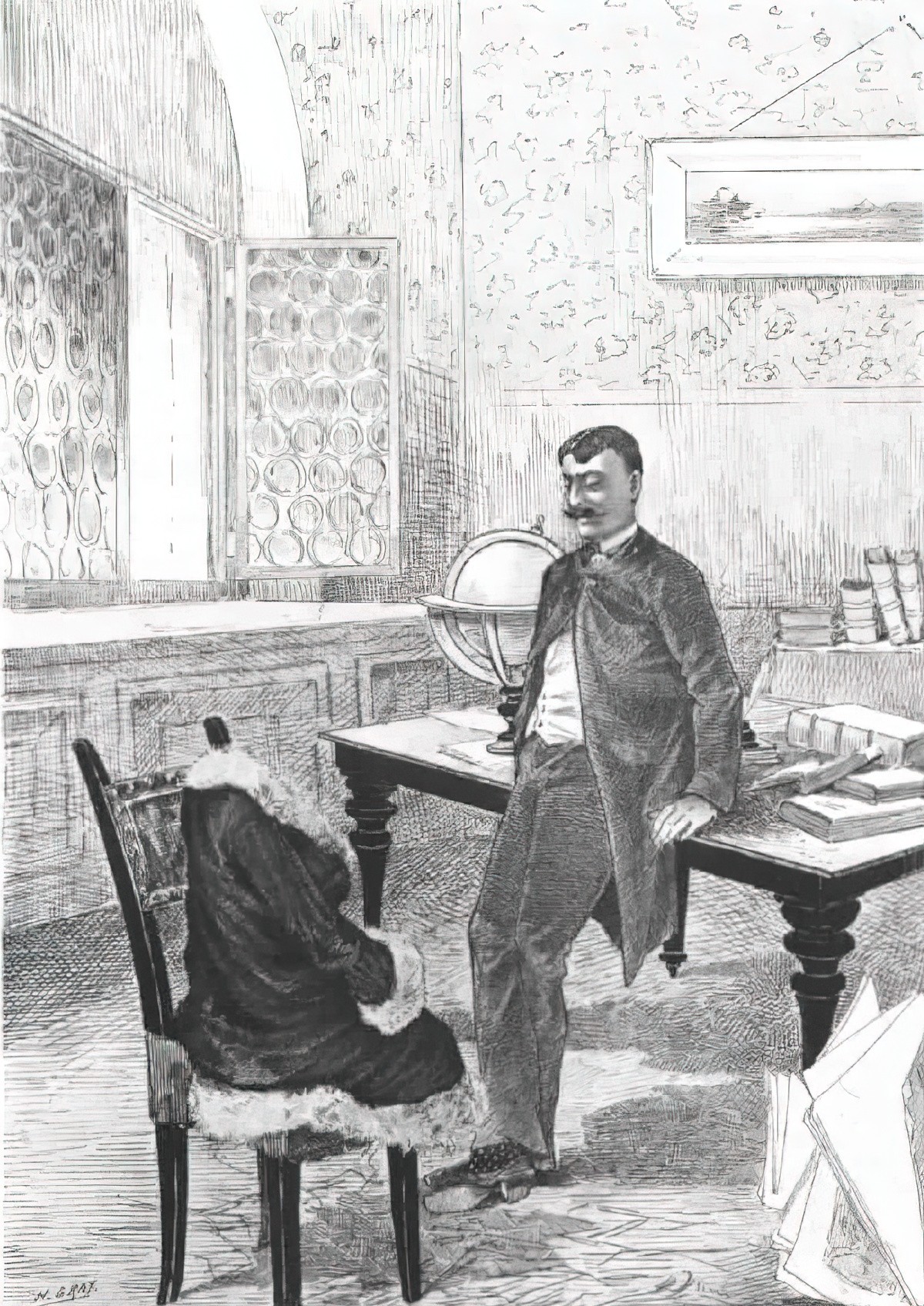

Here’s another story about a coat and a man called Joseph. ‘Le Manteau de Joseph Olénine’ is an 1886 French story by Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé. A man falls in love with a coat. Patricia Worth has provided an English translation here.

As I’m sure Cinderella’s prince did with the glass slipper, Joseph Olénine tries and determine the shape of the woman who owns it. So he stuffs the coat until it looks to him like a woman. This is basically a Pygmalion story. In the end, Joseph’s imaginary woman is so close to perfect that he doesn’t want to meet the coat’s real owner for fear of disappointment. (I wonder if Cinderella ever lived up to the Prince’s image of her as a dainty person?)

We are invited to judge Joseph Olénine. Is he better off with the coat instead of a woman? I don’t know, but I’m for and certain his marriage prospects were better off, if the guy really thought he could swap out a human for a… stuffed garment.

I’m reminded of the contemporary film Lars And The Real Girl, in which the coat is now a sex doll. However, the ending for Lars is different: The sex doll is an intermediary and temporary step between celibacy and satisfying love with a real woman.

The Horror Raincoat

Raincoats are getting to be a common item in the horror genre, to the point where you can almost expect a work to be a horror, or horror elements to suddenly enter a work, by the sight of a significant character wearing a raincoat.

Raincoat of Horror, TV Tropes

This raincoat is typically yellow, often worn by a small child. See, for instance, Dark Water.

It is an especially common trope in J-horror (Japanese horror), probably because yellow raincoats (for safety) are such an iconic image in Japan. Japan experiences a predictable rainy season, making umbrellas and raincoats necessary.

But of course Stephen King also likes a good horror raincoat. You probably know the one.

Cloaks and Coats As Invisibility Clothing

When used as a verb, ‘to cloak’ means to hide or conceal something.

The invisibility cloak is an ancient idea.

- The Irish God Lugh (or Lug) had a cloak that allowed him to pass unnoticed through the entire Irish army and rescue his son.

- Manannan mac Lir is another Irish god who owned an invisibility cloak.

- Alberic, a dwarf character from heroic German legend, also had one.

- In Japan, trickster creature the tengu wears a magic invisibility cloak called a kakuremino.

Hooded cloaks function symbolically as masks. Someone in a hooded cloak doesn’t need to be wearing a magic invisibility cloak — they become invisible because others aren’t noticing them. Certain creatures from folklore, for instance the cabiri, wear hoods covering their heads to imply visibility. (Cabiri are earth-god symbols personified as dwarfs, thought of as deities who watch over shipwrecked men.)

In modern stories, the hoodie (hooded sweater) functions in the same way. The Grim Reaper wears a hooded cloak, suggesting he walks among us, mostly unseen.

In the TV series You, Joe Goldberg stalks a woman he met in the book store he manages. The story requires Joe to follow Guinevere Beck physically as well as through cyber space. At times Joe is eavesdropping on Guinevere as she talks to her friends in bars. The storytellers simply dress him in regular clothes, sometimes a baseball cap, and he is effectively rendered invisible. Look at Joe’s ‘invisibility cloak’ below. It’s the most nondescript jacket possible. It doesn’t even have buttons.

Is this invisibility a stretch? Clearly. But we are willing to accept it because this symbolism is so ancient.

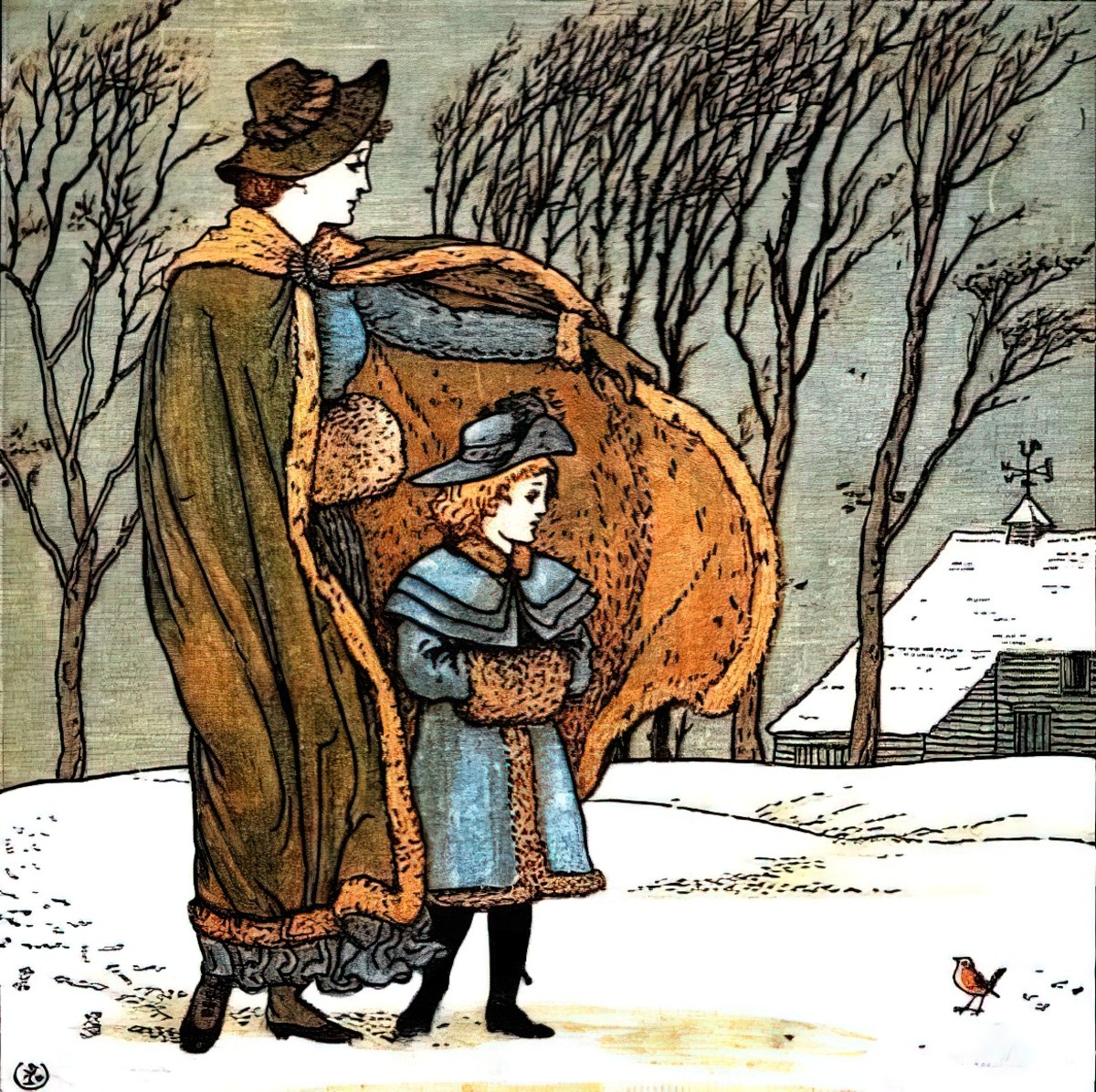

Cloak As Identity

Peter [Rabbit] must shed his shoes and coat in order to save himself, but this shedding also, tellingly, costs him his visual distinctiveness: bounding away from the gooseberry net in the next illustration, he is less “Peter,” treasured son, and more “Rabbit,” garden pest, identifiable only by his position alongside the text. Our sympathies, and the sympathies of the narrator, remain with him, largely due to the mechanics of the perspective in the illustrations: “Beatrix Potter portrayed the world from a mouse’s – or rabbit’s – or small child’s eye view. The vantage point in her exquisite watercolours varies from a few inches to a few feet from the ground, like that of a toddler” (Alison Lurie, Don’t Tell The Grown-ups). We see the world through Peter’s eyes, and therefore, identify with him. This perspective also speaks to Potter’s particular construction of childhood (one that would be revisited in E.B. White’s portrayal of Wilbur): littleness and vulnerability, curiosity and an urge to disobedience, hunger, and the fear that comes from being small in a frightening and predatory world.

Anglelina Sbroma

In some parts of the world, say China, people don’t typically wear secondhand clothes. Once worn, clothing becomes a part of that person.

In some ancient stories, to steal someone else’s cloak is to steal their personhood. It’s basically identity theft.

Take the story of The Curse of the Stolen Cloak. Servandus was a Roman who lived in Britain around 1,700 years ago. Someone nicked his cloak. Servandus wasn’t happy. So he asked a god to destroy the culprit. We know this happened because in 2006 archeologists uncovered a curse tablet in Leicester, England.

To the god Maglus, I give the wrongdoer who stole the cloak of Servandus. Silvester, Riomandus (etc.) … that he destroy him before the ninth day, the person who stole the cloak of Servandus

We don’t know if the culprit was ever caught or if the curse worked. It’s easy to forget that in ancient times clothing was super expensive and also super necessary. To steal someone’s clothing that kept them warm was an offence bordering on manslaughter, especially in cold climes.

On top of that, a cloak symbolically helps a person to change their identity.

As well as changing someone’s identity, a cloak can confirm it. In the Bible, Saint Martin gives half of his cloak to a beggar. In practical terms, now neither of them is all that warm. The act symbolises Saint Martin’s charitable nature. Nick Bland’s The Very Cranky Bear sort of works with this plot. A sheep donates her fleece to keep a cranky bear happy. (I have some ideological issues with it.)

It’s kind of funny to think that a coat can function as a disguise, or completely change someone’s identity when in reality we generally recognise people very well, even from the back view.

More Coats In Children’s Literature

The Emperor’s New Clothes by Hans Christian Andersen involves a coat, along with all his other items of clothing. This is another story in which clothing can deceive, and the lack of it reveal.

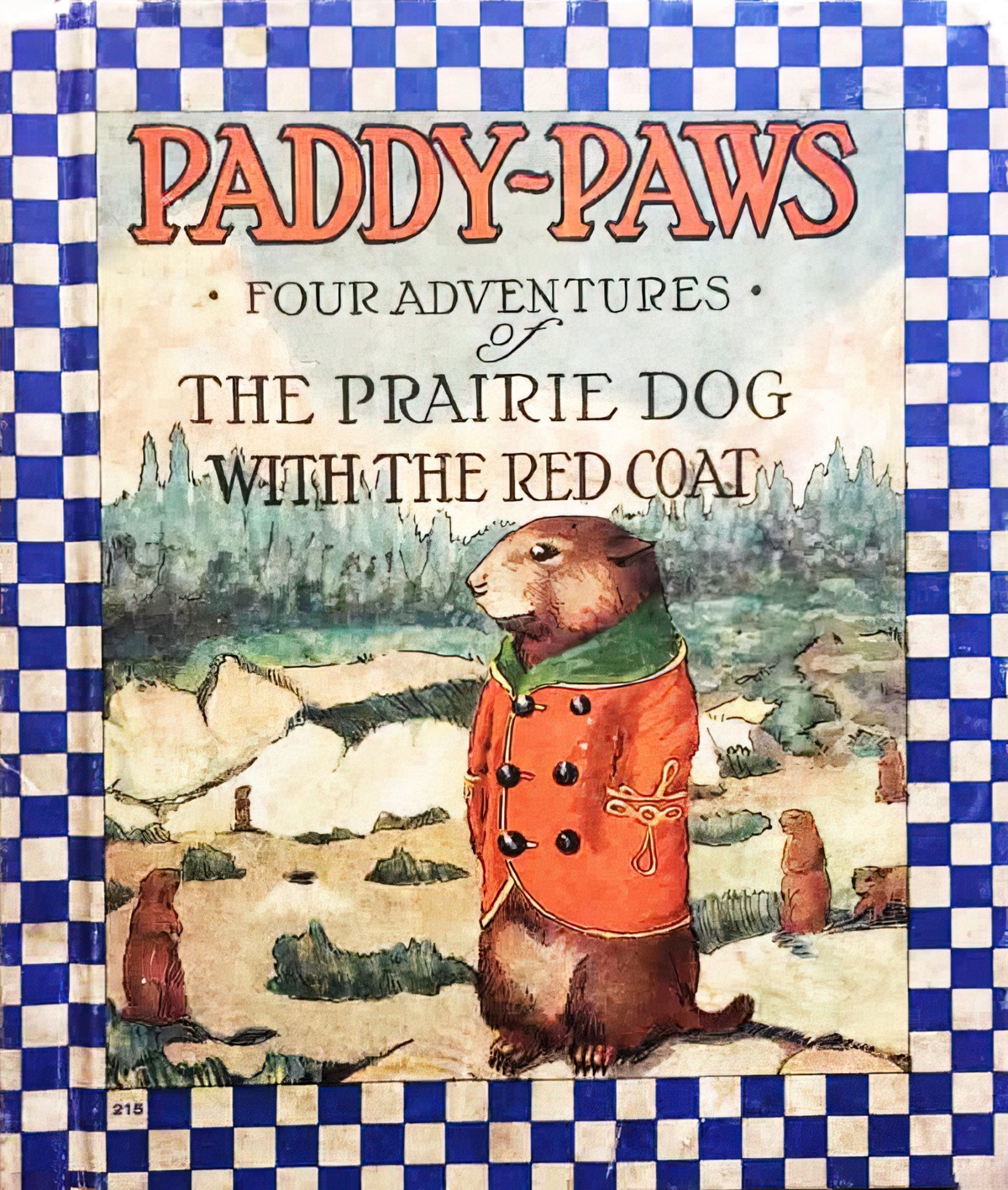

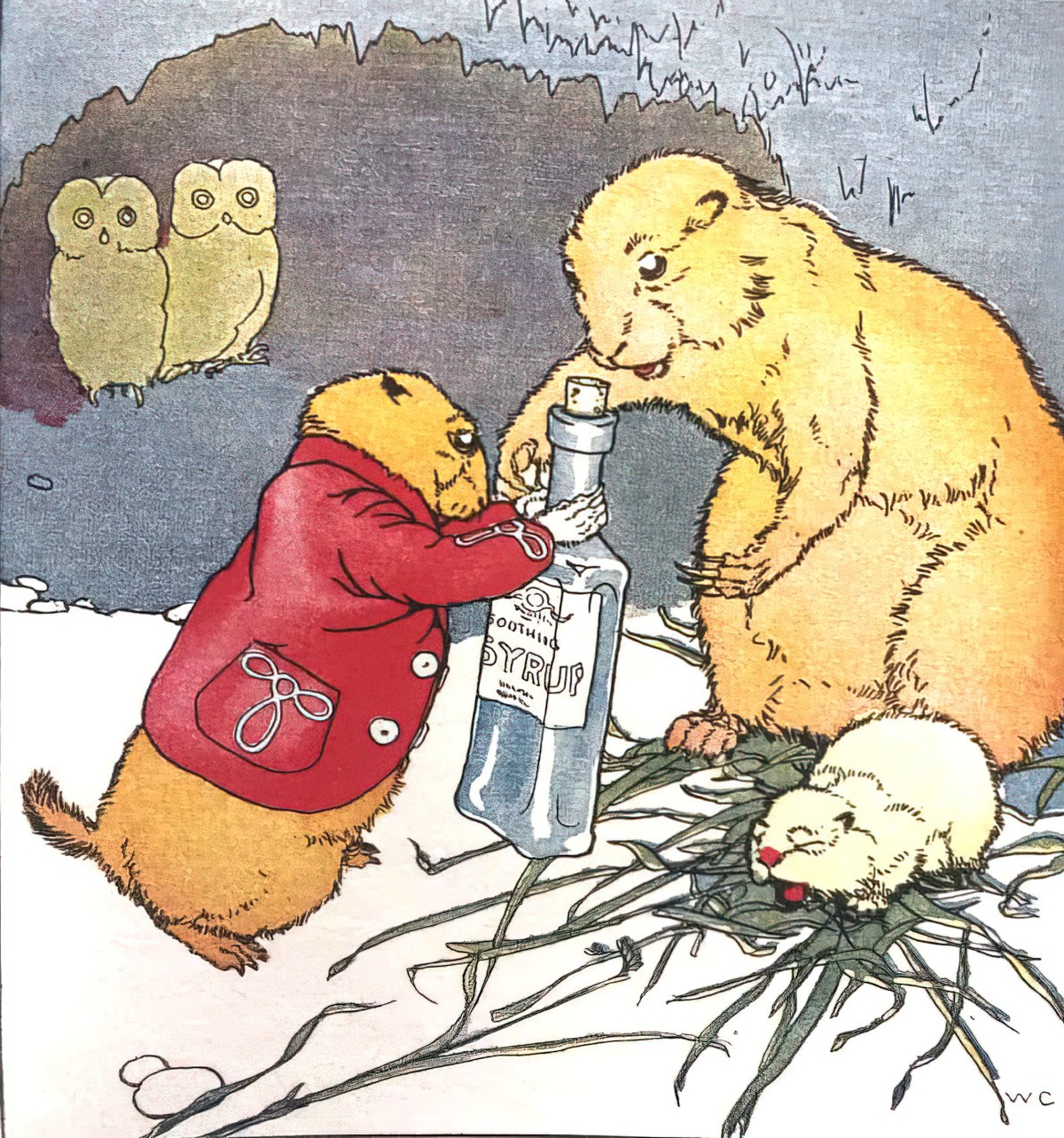

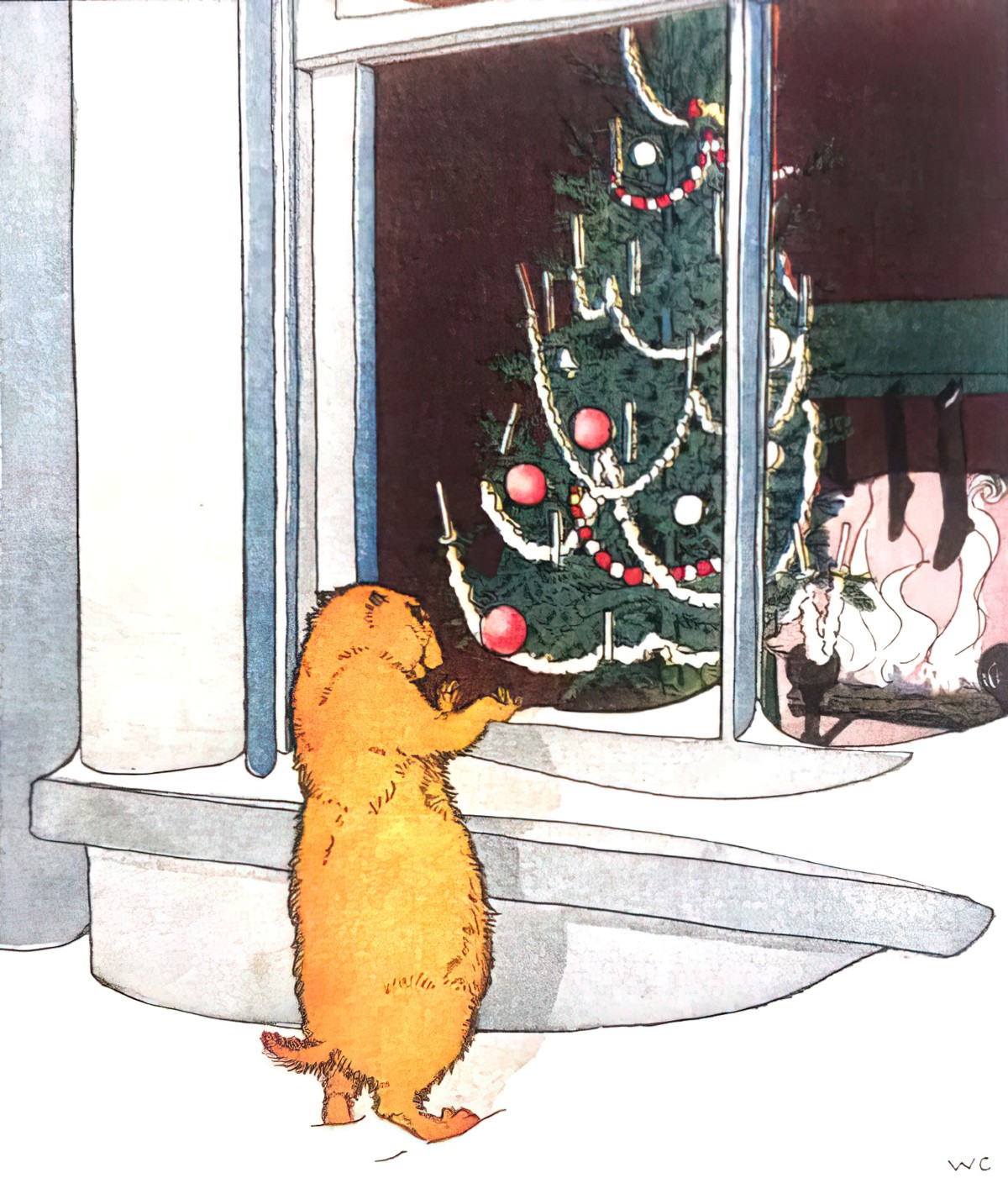

Paddy-Paws Four Adventures of the Prairie Dog With the Red Coat first published 1914 written by Grace Coolidge, illustrated by Warner Carr

2yo referred to her coat pockets as “snack holes” and this is what I shall forever call them

Rebecca Caprara (@RebeccaCaprara) February 23, 2018

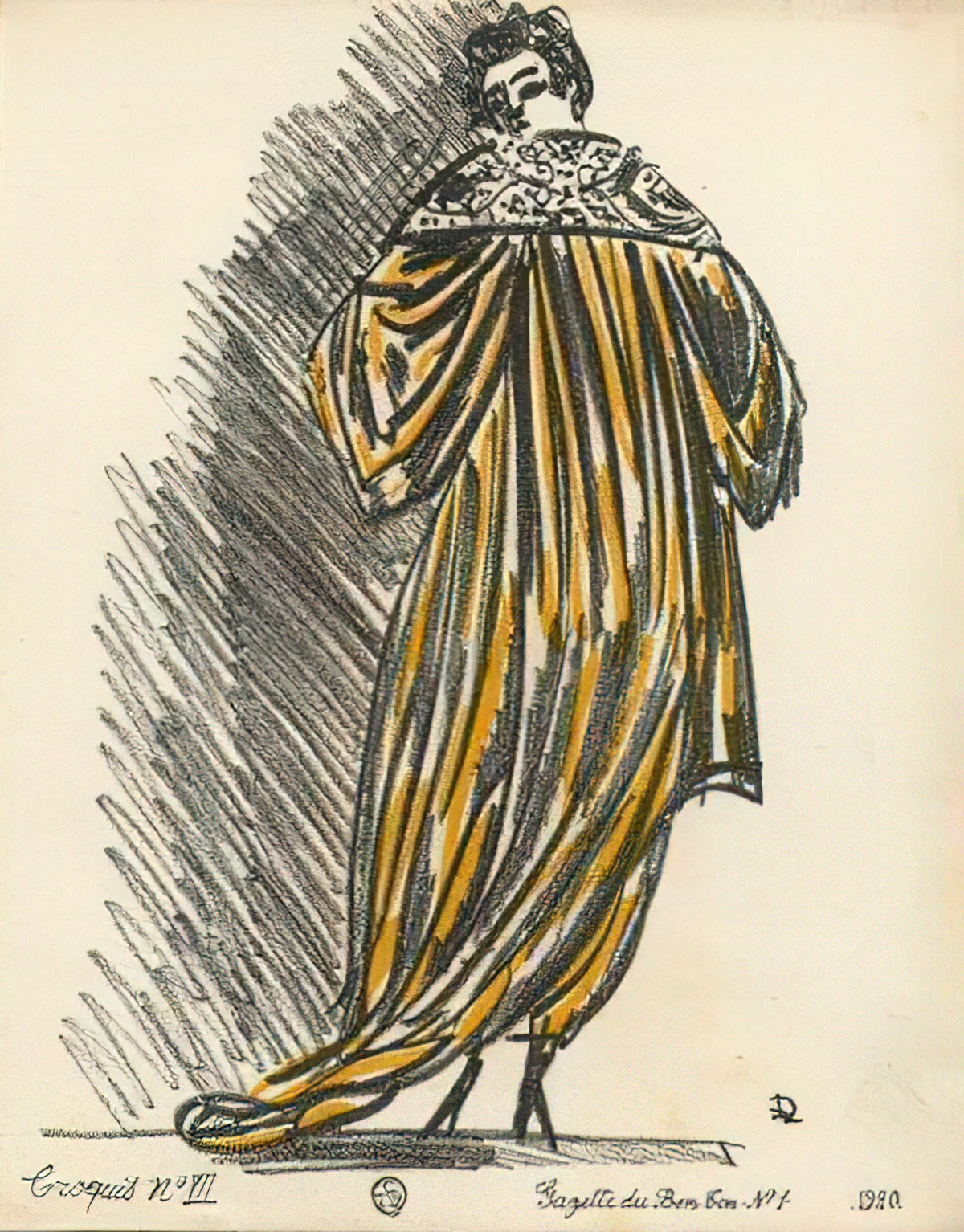

Header illustration (1920) is by illustrator Raoul Dufy and is called “Evening Coat by Paul Poiret”. It is a pochoir print from the Gazette du Bon Ton. Pochoir means “stencil” in French and refers to the technique of making fine limited editions of stencil prints, also known as “hand coloring”.

The Shetlanders once repelled a band of marauders with the clever use of cloaks covered in herring skins in the tale ‘The Hallamas Mareel ‘ The figure in the foreground is a skekler, dressed in the traditional straw costume for Hallamas (New Year)Art self#FolkloreThursday pic.twitter.com/tGvyoDC8ls

— Katherine Soutar is ‘mildly disturbing’ (@Kate_Dancingcat) July 22, 2021

The Shetlanders once repelled a band of marauders with the clever use of cloaks covered in herring skins in the tale “The Hallamas Merel”. The figure in the foreground is a skekler, dressed in the traditional straw costume for Hallamas (New Year).

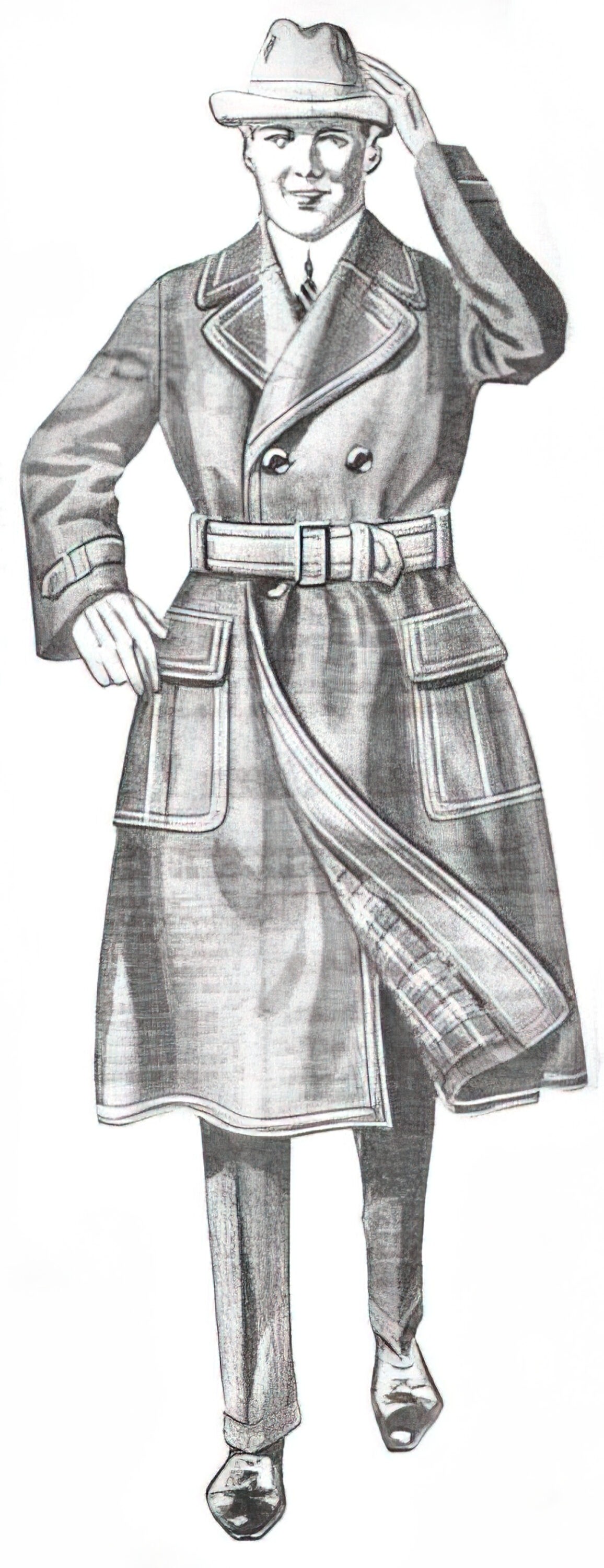

TRENCH COAT

Object Lessons is a Bloomsbury series of short, beautifully designed books about the hidden lives of ordinary things. This interview focuses on Trench Coat by Dr. Jane Tynan, published in 2022.

We think we know the trench coat, but where does it come from and where will it take us? From its origins in the trenches of WW1, this military outerwear came to project the inner-being of detectives, writers, reporters, rebels, artists and intellectuals. The coat outfitted imaginative leaps into the unknown. Trench Coat tells the story of seductive entanglements with technology, time, law, politics, trust and trespass. Readers follow the rise of a sartorial archetype through media, design, literature, cinema and fashion. Today, as a staple in stories of future life-worlds, the trench coat warns of disturbances to come.

New Books Network

‘Robbers’ were once stealers of robes, and ‘escaping’ was about throwing off your cape. How language never lost its fashion mojo, by Susie Dent, July 2021