Generally speaking, a lot of thought goes into choosing character names. Sometimes a name is chosen because it is appropriate to the age of the character, culture and era. Sometimes the name is aesthetically pleasing. Sometimes the name is symbolic.

NEW NAME, NEW SELF

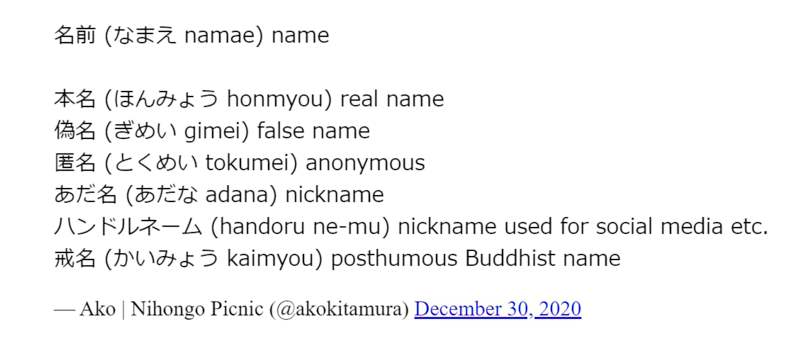

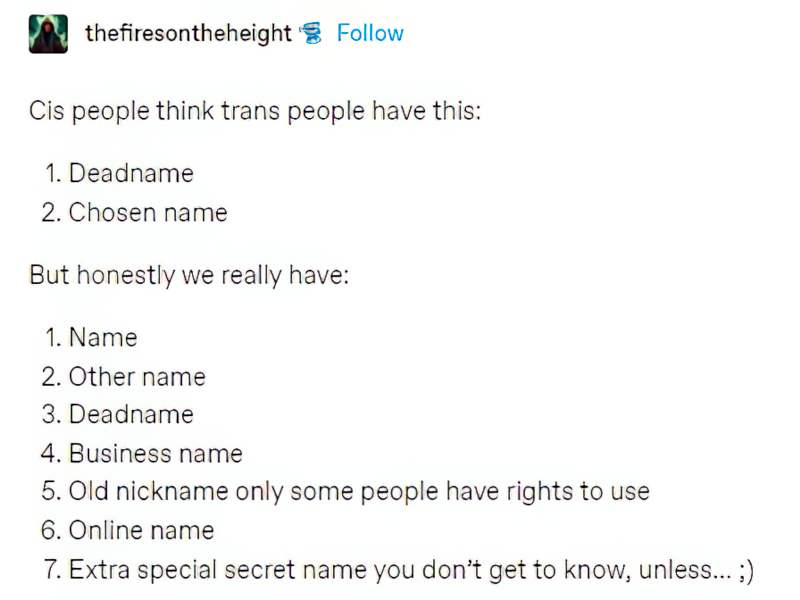

We all have many names. (In some cultures more than others.)

When Walter White changes his name to Heisenberg, he has created an entire alter ego. Breaking Bad is a modern superhero story. We are familiar with superheroes, ever since Super-man/Clark Kent. This is such obvious symbolism it doesn’t hold up to much more scrutiny than that.

Before Mazer invented himself as Mazer, he was Samson Mazer, and before he was Samson Mazer, he was Samson Masur—a change of two letters that transformed him from a nice, ostensibly Jewish boy to a Professional Builder of Worlds—and for most of his youth, he was Sam, S.A.M. on the hall of fame of his grandfather’s Donkey Kong machine, but mainly Sam.

opening to Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, a 2022 novel by Gabrielle Zevin

The letter arrives on a Friday. Slit and resealed with a sticker, of course, as all their letters are: Inspected for your safety-PACT. It had caused confusion at the post office, the clerk unfolding the paper inside, studying it, passing it up to his supervisor, then the boss. But eventually it had been deemed harmless and sent on its way. No return address, only a New York, NY postmark, six days old. On the outside, his name-Bird-and because of this he knows it is from his mother.

He has not been Bird for a long time.

We named you Noah after your father’s father, his mother told him once. Bird was all your own doing.

The word that, when he said it, felt like him. Something that did not belong on earth, a small quick thing. An inquisitive chirp, a self that curled up at the edges.

The school hadn’t liked it. Bird is not a name, they’d said, his name is Noah. His kindergarten teacher, fuming: He won’t answer when I call him. He only answers to Bird.

Because his name is Bird, his mother said. He answers to Bird, so I suggest you call him that, birth certificate be damned. She’d taken a Sharpie to every handout that came home, crossing off Noah, writing Bird on the dotted line instead.

That was his mother: formidable and ferocious when her child was in need.

In the end the school conceded, though after that the teacher had written Bird in quotation marks, like a gangster’s nickname. Dear “Bird,” please remember to have your mother sign your permission slip. Dear Mr. and Mrs. Gardner, “Bird” is respectful and studious but needs to participate more fully in class. It wasn’t until he was nine, after his mother left, that he became Noah.

His father says it’s for the best, and won’t let anyone call him Bird anymore.

If anyone calls you that, he says, you correct them. You say: Sorry, no, that’s not my name.

It was one of the many changes that took place after his mother left. A new apartment, a new school, a new job for his father. An entirely new life. As if his father had wanted to transform them completely, so that if his mother ever came back, she wouldn’t even know how to find them.

opening to Our Missing Hearts, a 2022 novel by Celeste Ng

LOSS OF NAME, LOSS OF TRUE SELF

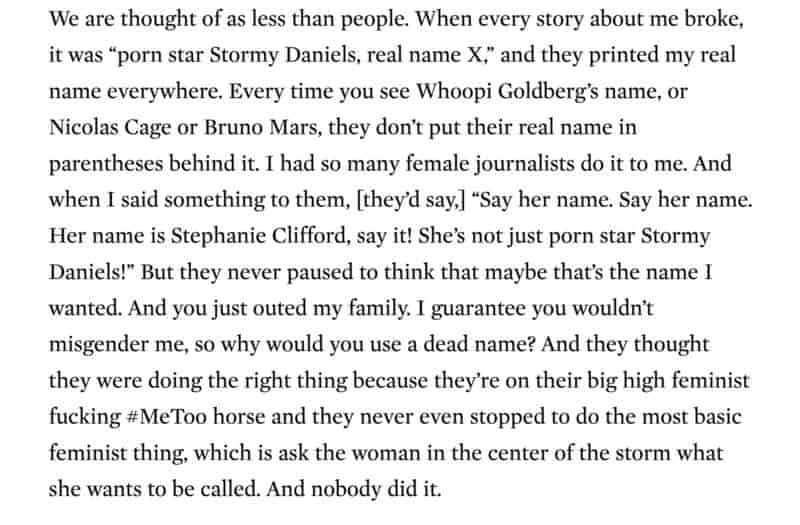

This is a pervasive idea throughout literature, even though we obviously don’t subscribe to it in real life. Women in the West are still largely expected (and do) change surnames when marrying a man, yet we don’t believe she has lost a part of herself. When Chinese speakers immigrate to English speaking countries they quite often adopt a name which is pronounceable and memorable for native English speakers. Do those immigrants with several names feel they have lost a part of themselves? Or do they feel their name is simply the label they attach to themselves in certain contexts?

How many names do you have?

My name (Lynley) is a ridiculous tongue-twister to native Japanese speakers, so while I lived in Japan my name was switched to my last name (Stace). It’s common for even young Japanese people to go by their last name in Japan — it seems to be a bit of a lucky dip whether you’re known by your first or your last name, whereas in my home country (New Zealand) young people very rarely go by their last name, unless there’s a specific reason for doing so. (One of my brothers made friends with all of the Davids in his year so he, too, went by the name Stace for clarity purposes.) I have never gone by our last name Stace outside Japan, though I like to keep it for use online. I felt nothing about me changed when my moniker changed.

That doesn’t tend to be true when it comes to fictional characters.

Take the Hayao Miyazaki film Spirited Away. Chihiro becomes Sen — the Chinese reading of a shortening of her Japanese name — until she can escape from the enslaving world ruled by the bath woman.

After Yubaba steals part of Chihiro’s name, Haku warns Sen not to forget her former name or she will be trapped in the spirit world forever. Sen must remember the qualities that make her who she is and remain true to them, even though her name, the one word that defines her, has changed. Sen succeeds in keeping her identity and also helps Haku regain his, ultimately freeing them both. Haku is living proof of the dangers inherent in forgetting one’s true identity. Names are of fundamental importance in the spirit world, and those in power keep their control by stealing and changing names. Only those characters with the inner strength to hold onto their names and identities can free themselves.

Spark Notes

After The First Death is young adult thriller from the 1970s by Robert Cormier. This story contains similar name symbolism — characters forfeit their names.

Part One opens with a first person narrator who feeds us his name in dribs and drabs.

Part Two switches point of view. These Middle Eastern terrorists have lost their names entirely, trained to forget them by means of dedicating themselves to the cause. Cormier is careful to emphasise that these terrorist, foreign boys have names — or had them. This turns them into individuals. The sociopathic terrorist among the group shows us his true colours by angering a waitress when he chooses to ignore her wishes to be called by her own name rather than one he has designated. By taking her name he demonstrates his ability to turn off empathy. This guy is therefore posited from the beginning as a cold-blooded killer.

“That will be all, Myra,” Artkin said.

After The First Death by Robert Cormier

“What did you say?” she asked.

“I said, ‘That will be all, Myra.”

“My name’s not Myra,” the girl said.

Artkin smiled at her. “Of course it isn’t,” he said. But his voice suggested the opposite, his voice and his smile. They hinted wickedly of deep secrets.

“Well, it isnt,” she said. “My name’s Bonnie, although the priest didn’t like it because there’s no Saint Bonnie.”

“Please give us the check, Myra,” Artkin said, voice cold now, uninterested.

“I said my name’s not Myra,” she muttered as she totaled up the bill.

“Myra’s a nice name. It’s nothing to be ashamed of,” Artkin said.

Her face reddened, accentuating the acne, the pimples and small scabs. Artkin could do that to people, intimidate them, draw them into conversations they did not want to be drawn into, force the into confrontations.

“Think about it, Myra. How old were you when you were baptized? Two weeks, two months? Do you remember being baptized with the name Bonnie? Of course not. It’s what people have told you. Have you ever seen your birth certificate? Not he thing they give you when you go to City Hall for a copy, but the original? The one that says your name is Myra. You’ve never seen it, have you? But that doesn’t mean it does not exist. You have never seen me before but I exist. I have existed all this time. I might have been there when you were baptized, Myra.”

She stood there for a moment, the check in her hand, hesitant, doubtful, her eyes wary, and Miro knew that this was what Artkin had worked to do: create this split second of doubt and hesitation. He knew that he had reached his mark, drawn blood. Then the moment vanished. The girl flung the check on the table.

“You’re nuts,” she said, and turned away, shaking her head at all the strange people loose in the world.

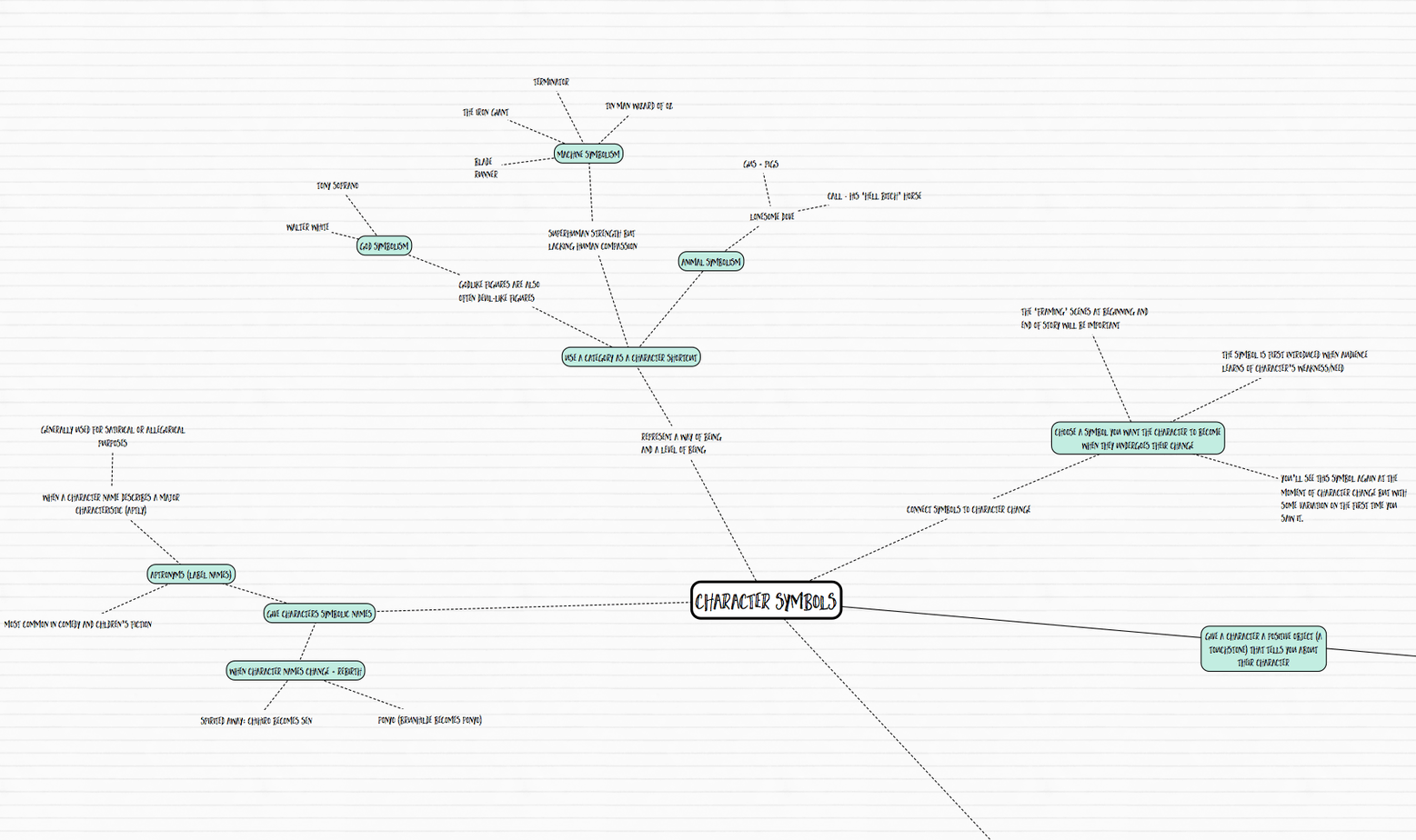

NAMES AS CHARACTER SYMBOLS

If you have a name it can set someone in place. I have a great friend in California, the Irish novelist Brian Moore. We were having dinner one night and Brian said that when he was a newspaperman in Montreal a local character there was named Shake-Hands McCarthy. I said, Stop! Are you ever going to use that name? He said, No, let me tell you about him. I said, No, I don’t want to know anything about him. I just want to use that name. So the name turned up in True Confessions.

JOHN GREGORY DUNNE

A character’s name is a children’s story is quite often symbolic. Symbolic names are also common in comedy, but are less frequently seen elsewhere, in stories that aim for mimesis (realism). In the real world, after all, people’s personalities are not connected to their names. (And even if your teacher is called Mrs Bellringer and your dermatologist is called Dr Healsmith, that isn’t useful in a suspenseful crime novel.)

Also known as:

- a label name

- allegorical name

- When the name of a fictional character describes their personality or occupation, it is called an aptronym. Or sometimes aptonym (without the ‘r’)

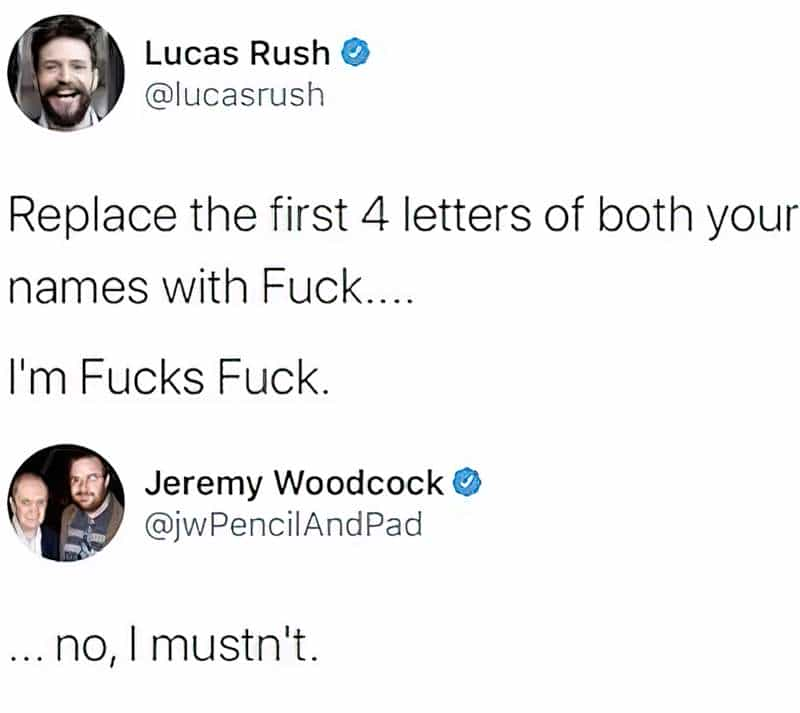

Why do guys named Timothy go by Tim when they could go by Moth

Elysia Paige

I am well aware that my name is ridiculous. It was not ridiculous before I took this job four years ago. I’m a maid at the Regency Grand Hotel, and my name is Molly. Molly Maid. A joke. Before I took the job, Molly was just a name, given to me by my estranged mother, who left me so long ago that I have no memory of her, just a few photos and the stories Gran has told me. Gran said my mother thought Molly was a cute name for a girl, that it conjured apple cheeks and pigtails, neither of which I have, as it turns out. I’ve got simple, dark hair that I maintain in a sharp, neat bob. I part my hair in the middle—the exact middle. I comb it flat and straight. I like things simple and neat.

the opening to The Maid, a 2023 cosy mystery by Nita Prose

FIFA president Gianni Infantino (That is correct. In a powerful demonstration that nominative determinism lives on, the man’s name basically translates to “Man Baby”) chose the eve of the World Cup final to explain to female players that it was their responsibility to achieve equal treatment.

An infamous Spanish kiss overshadowed meritorious women doing their job — can you believe it? by Annabel Crabb

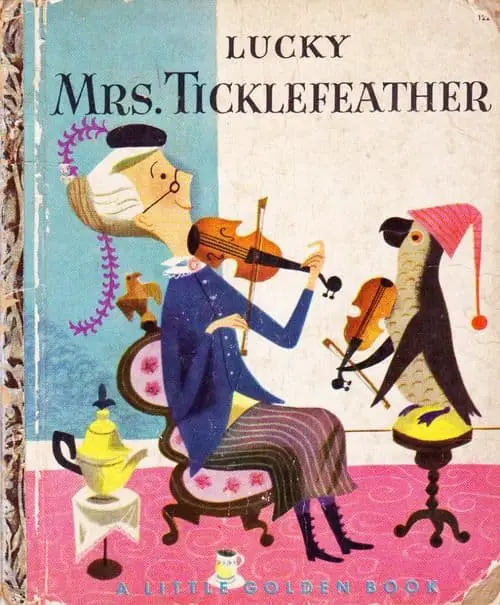

SYMBOLIC NAMES IN CHILDREN’S STORIES

- Enid Blyton loved label names — think Watzisname, Dame Washalot, Silky and Moonface. from The Magic Faraway Tree series. These names were very literal. Blyton steered clear of ironic symbolism.

- The Seriously Extraordinary Diary Of Pig by Emer Stamp features some farmers called Mr and Mrs Sandal, who happen to be vegetarian. This is a symbolic name for the adult co-reader, as I’m not sure young readers would always know how heavily sandals are associated with vegetarianism — mostly because this was true back in the 1970s, I think.

- The entire cast of Mr Men and The Smurfs

- Beautiful Bella from the Twilight series

Some names are symbolic mainly because of the history of stories that precede them. In children’s literature, having Little before your name means chances are slim of you ever becoming Big. You’ll probably die.

DO SYMBOLIC NAMES COMPROMISE REALISM?

The middle grade novel A Long Way From Chicago by Richard Peck is filled with characters with colourful names. Early in the story we meet the Cowgills. The child narrator lampshades the symbolism of the name by writing: “It may have been just a coincidence that a family named Cowgill owned the dairy. I never knew.” This lampshading is necessary because Peck is basically going for nostalgic historical realism. It also leads to some humour.

It works because sometimes a real person does seem to have a symbolic name, in which case it’s comically coincidental. Donald Trump springs to mind. I do know a teacher called Mrs Bellringer.

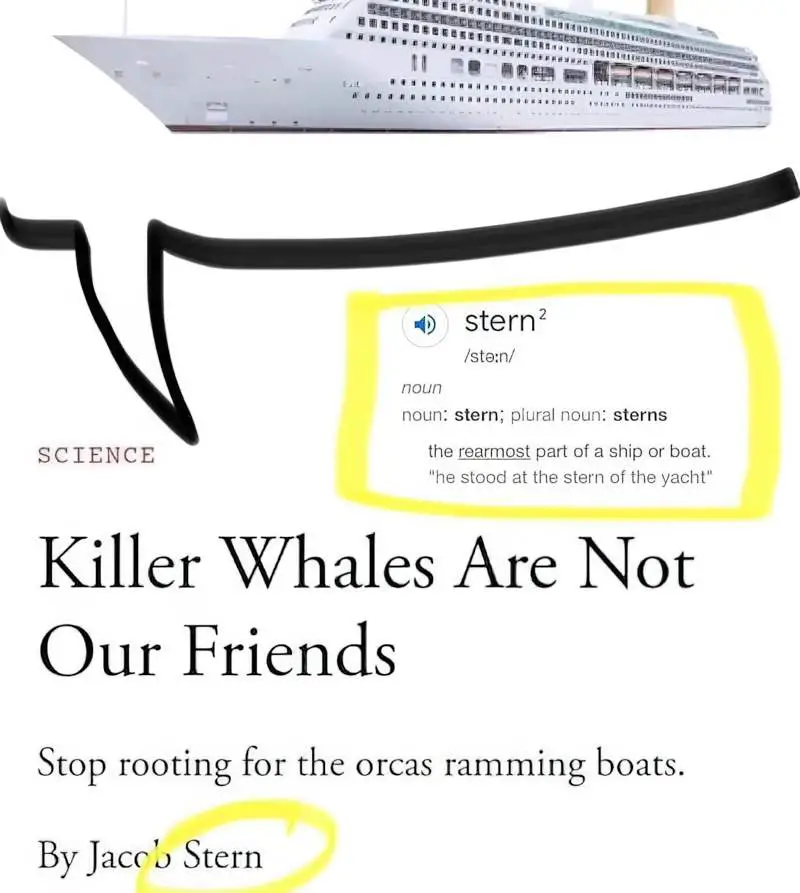

A Slate culture writer makes a good case for avoiding subtlety, and he’s talking about stories for adults.

Writers of popular adult stories seem to subscribe to this view, though symbolic names for adult characters tend to take on a different form — the main characters in True Detective are called Hart and Cohle, which is symbolically linked (Heart and Coal) to their personalities and character arcs. This weaker connection is safer if you’re hoping to avoid metafiction.

Another very similar example occurs in The Sixth Sense, starring a main character called Malcolm Crowe. Crowe is dead, so one could argue Shyamalan is giving us a big clue in with the character’s name. Cole Sear: “Cole” compared to “coal” which is black like death. “Sear” compared to “seer,” someone who has keen insight. Of course, Cole has the insight that Malcolm is a ghost (“I see dead people”).

SYMBOLIC NAMES IN STORIES FOR ADULTS

Stories for adults also feature characters with symbolic names, especially if they are comedies. Will Freeman of About A Boy is one example. Tied down to no one, this man-child really does live under the illusion of free will.

PHONETICALLY APPROPRIATE NAMES

An excellent example of this is Dwight Kurt Schrute of the American Office, and I have wondered if his name is inspired by Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp, whose full nam would be much improved without the ‘Berry’.

INITIAL LETTERS LINKING CHARACTERS TOGETHER

This trick is surprisingly common once you start noticing it, especially in stories which work at a highly symbolic level. In this technique, two characters have names which begin with the same letter or sound. These characters will reveal themselves as intricately linked as the story progresses.

- Laura and Laurie in “The Garden Party” by Katherine Mansfield

- Leda and Lyle in The Lost Daughter directed by Maggie Gyllenhaal, written by Elena Ferrante

- Phil and Peter in The Power of the Dog directed by Jane Campion, written by Thomas Savage

RELATED TERM

Tuckerizing. Named after Wilson Tucker, the practice of introducing as peripheral characters, or offstage icons, names recognizable to the reader. (For example, naming the Moon’s capital Heinlein and its main street La Rue de la Professor Bernardo de la Paz.) A subclass of rewarding the careful reader.

Glossary of Terms Useful When Critiquing Science Fiction

FURTHER READING

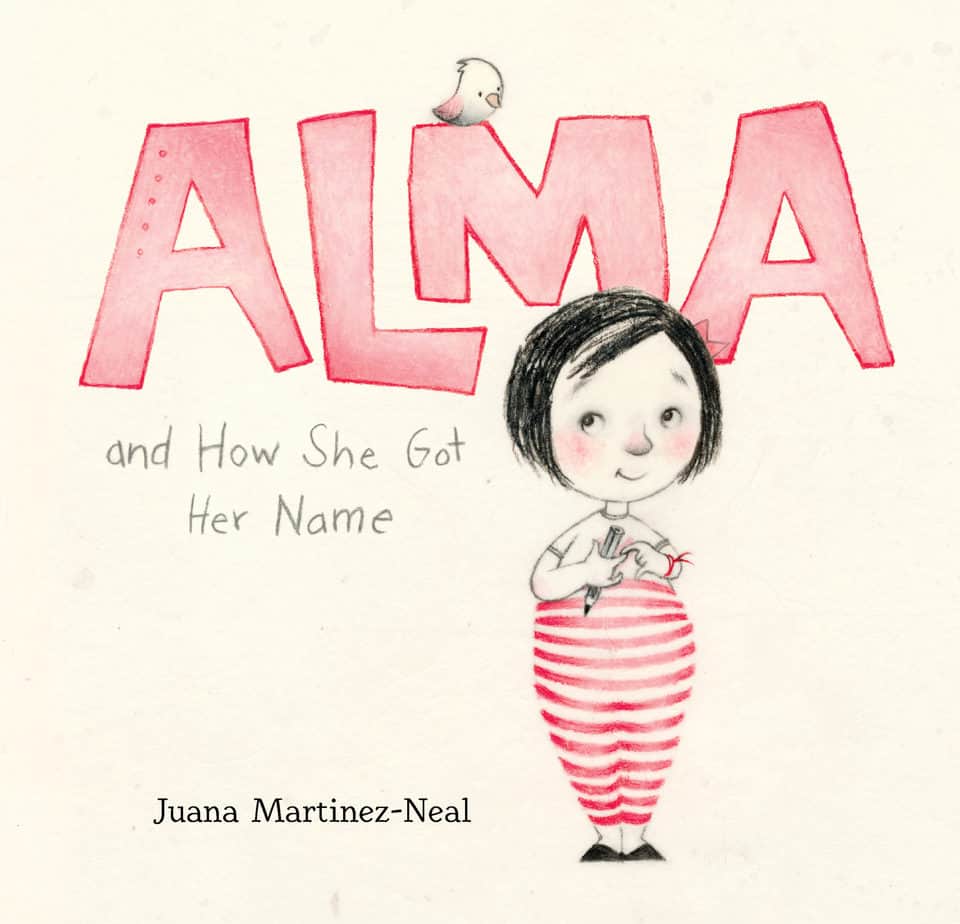

If you ask her, Alma Sofia Esperanza José Pura Candela has way too many names: six! How did such a small person wind up with such a large name? Alma turns to Daddy for an answer and learns of Sofia, the grandmother who loved books and flowers; Esperanza, the great-grandmother who longed to travel; José, the grandfather who was an artist; and other namesakes, too. As she hears the story of her name, Alma starts to think it might be a perfect fit after all — and realizes that she will one day have her own story to tell. In her author-illustrator debut, Juana Martinez-Neal opens a treasure box of discovery for children who may be curious about their own origin stories or names.

As in the universe every atom has an effect, however miniscule, on every other atom, so that to pinch the fabric of Time and Space at any point is to shake the whole length and breadth of it, so that to change a character’s name from Jane to Cynthia is to make the fictional ground shudder under her feet.

John Gardner, The Art of Fiction: Notes on Craft for Young Writers

Header illustration: Easy Answers to Hard Questions pictures by Susan Perl text by Susanne Kirtland (1968) where do names come from