Love it or loathe it, the superhero is an ambivalent archetype in storytelling, useful to either bolster the conservative status quo, or subvert it.

SUPERHERO FILMS ARE SQUEEZING OUT OTHER FILMS

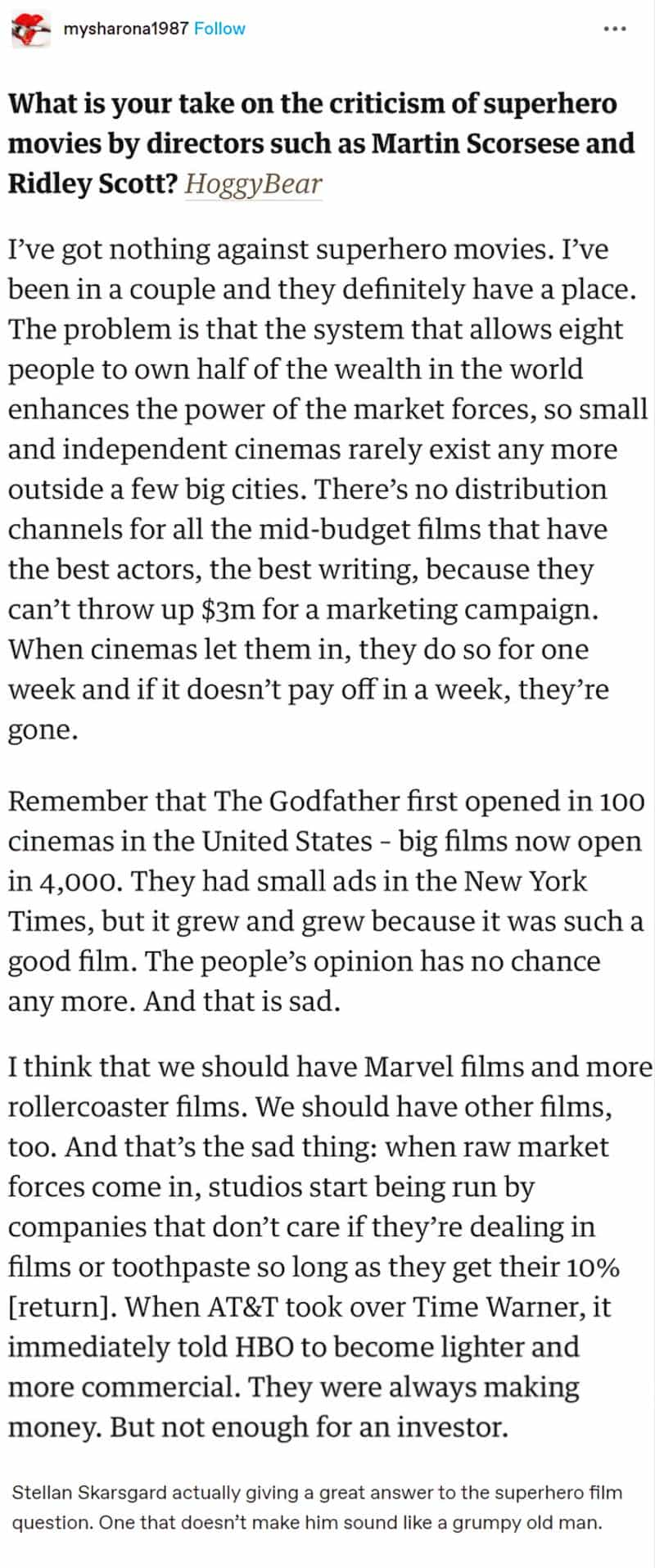

[The superhero movie] crowds out other movies so that a lot of the comedies or the literary adaptations or just the adventurous personal films that were so much a part of my movie-going and movie-going experience have been really squeezed out. It’s harder for audiences to find movies worth taking a chance on, and it’s harder for me to find those movies to write about — those occasions where I can say, Hey listen, here’s something, here’s a movie, not an esoteric, out-of-the-way teeny-tiny indie movie, but a Hollywood movie that’s powerful, that’s ambitious, that’s surprising, that’s doing something new that you should go out and see. And I need to have a certain amount of those, you know, to do my job and enjoy my job and to feel like my job is fulfilling and meaningful.

Our Film Critic on Why He’s Done With the Movies, Thursday 23 March 2023 edition of The Daily (NYT podcast).

SUPERHERO NARRATIVES AS AUTHORITARIAN POWER FANTASIES

Superhero Movies Are Fascist Fantasies

With notes from the Public Intellectual Podcast with Jessa Crispin, interviewing Peter Biskind (American cultural critic)

- This discussion is America focused, though America influences the whole world.

- Culture influences politics. This is not necessarily a popular idea. It’s not taken seriously, anyhow. A lot of people like to think ‘entertainment is entertainment’ and because we know entertainment when we see it, there’s huge resistance to believing what we consume as entertainment can influence our political views.

- A lot of the time, this discussion focuses only on ‘violence in video games’.

- It’s very difficult to disentangle entertainment from cultural change.

- Entertainment enhances social change. It’s not merely reflected. There’s a kind of echo chamber effect. And specific works can absolutely effect social change.

- The vigilante story (e.g. the revenge Western) has been very popular, and may have helped pave the way for President Trump, who doesn’t follow the rules. Moreover he prides himself on that. He said he could stand in the middle of Times Square, shoot someone and not lose any votes. He’s basically a movie hero (or sympathetic antihero).

- Westerns were a phenomenally popular for much of the 20th century, and these were followed by Charles Bronson characters. Now no one thinks twice about all sorts of nasty, over-the-top revenge arcs which are far, far more XX than Shakespeare’s an eye for an eye view of revenge, in which the phrase means “If someone takes out your eye, you may take out their eye, but no more than one.”

- Christopher Nolan is a director who is universally acclaimed though his politics are obviously right-wing. In Dunkirk Nazis are completely erased from the film. It’s easy to read the film as an apology for Brexit, and Britain going-alone-ism. The film flatters the English for being the last bastion against the Germans but never mentions the Germans until deep into the film.

- A function of these apocalypse movies is that the disasters justify extreme measures, leading to a general extremism. Walking Dead — do anything you can to survive. Justified selfishness. It’s a centrist series — a laboratory for trying on extreme measures for size and then deciding we have to pull back — I’m turning into the enemy that I’m fighting. Again and again, Rick (head of the team of survivors) is pushed further and further to extremes. In one scene he’s captured by loutish human survivors. He jumps on one and takes a bite out of its neck (behaving like a zombie). Later he repudiates that behaviour. The show keeps exploring the same scenes over and over with the same outcome, which is a problem the show has. Also interesting, the humans are just as bad as the zombies if not worse. They’re more dangerous, because they can still think and scheme and plot, whereas the zombies just trudge along.

- Theoretically, Batman had a code like cowboys had a code in Western movies. The original illustrator of Batman was extremely right wing. But in Nolan’s The Dark Knight the police are corrupt, so Batman has to become a vigilante, and he breaks the code he’s supposed to abide by. But the movies don’t admit that. The Joker points out that he’s killed five people. “Even for me that’s a lot.” The Joker admires him for his lethalness. At the end of the film Batman is walking back to the bat cave and is rewarded for his actions.

- Marvel comics are more into surveillance state themes than the Batman comics.

- The Ironman movies are well-written.

- In the Captain America movies the issues of surveillance state are debated, which makes them less right-wing than the Batman films.

- The Hollywood market is tilted towards China now. Action travels best. Shows that are character driven don’t carry as well. We’d rather spend $250m on a superhero spectacular than a medium budge on a film about human beings. They are serving a younger audience. Baby boomers and a couple of generations below them have abandoned movies for Netflix and other streaming services.

- Superhero movies attract super fans. Critics who dare to criticise superhero films are subject to death threats. These people intersect with Gamergate geeks/Trump supporters.

- Gaming has influenced superhero movies: winning (at any cost) is the goal.

LARGER-THAN-LIFE FOLK HEROES OF HISTORICAL PROTESTS

The superhero of comic books and blockbuster movies may be a quintessentially American invention, forever saving the world in skin-tight spandex. But the cultural DNA of the superhero can arguably be traced to a much older, more progressive, British tradition: the larger-than-life folk heroes of historical protests – General Ludd, Captain Swing, Lady Skimmington, and others; semi-fictional identities that ordinary protestors adopted, often dressing up in the process.

The Cuckoo Cage (CommaPress, 2022), edited by Ra Page, is a unique experiment, twelve authors have been tasked with resurrecting that tradition: to spawn a new generation of present-day British superheroes, willing to bring the fight back to British shores and to more progressive causes. From the dimension-jumping statue-toppler, to the shape-shifting single mum raiding supermarkets to stock local foodbanks, these figures offer unlikely new insights into shared, centuries-old political causes, and usher in a new league of proud, British (social justice) warriors.

New Books Network

Comics and Pop Culture: Adaptation from Panel to Frame

It is hard to discuss the current film industry without acknowledging the impact of comic book adaptations, especially considering the blockbuster success of recent superhero movies. Yet transmedial adaptations are part of an evolution that can be traced to the turn of the last century, when comic strips such as “Little Nemo in Slumberland” and “Felix the Cat” were animated for the silver screen. Along with Barry Keith Grant, Scott Henderson (Dean and Head, Trent University Durham GTA) compiled a rich group of essays that represent diverse academic fields, including technoculture, film studies, theater, feminist studies, popular culture, and queer studies. Comics and Pop Culture: Adaptation from Panel to Frame (University of Texas Press, 2019) presents more than a dozen perspectives on this rich history and the effects of such adaptations.

New Books Network

The Comic Book Film Adaptation: Exploring Modern Hollywood’s Leading Genre

When Marvel’s X-Men took the movie theaters by storm in the summer of 2000, the studios were both surprised and unprepared for the popularity of a comic book film. Over the last fifteen years, filmmakers have developed new ways to use modern movie techniques to adapt comic book characters into the 21st century culture. Liam Burke, media studies lecturer at Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne, Australia, interviewed film and comics professionals as part of his research for The Comic Book Film Adaptation: Exploring Modern Hollywood’s Leading Genre (University Press of Mississippi, 2015).

New Books Network

The Sign of the Joker: The Clown Prince of Crime as a Sign

From the time of his introduction in the Detective Comics in 1940s, the Joker is a character that has both fascinated and repelled the collective psyche of the fans of the comic subculture and beyond.

In a new book titled The Sign of the Joker: The Clown Prince of Crime as a Sign published in the Brill Research Perspectives series, Joel West of the University of Toronto, Canada, analyzes the history and personality of the character, speculates on the character’s sexuality, and ultimately suggests what exactly gave the Joker his iconic status today.

New Books Network

Batman and The Joker: Contested Sexuality in Popular Culture

In Batman and The Joker: Contested Sexuality in Popular Culture (Routledge, 2020), Chris Richardson presents a cultural analysis of the ways gender, identity, and sexuality are negotiated in the rivalry of Batman and The Joker. Richardson’s queer reading of the text provides new understandings of Batman and The Joker and the transformations of the Gotham Universe throughout its 80-year existence. In particular, Richardson investigates how artists, writers, and fans engage with, challenge, and interpret gendered and sexual representations of this influential and popular rivalry. Fans of Batman and The Joker will find this work engaging and applicable across a range of scholarly fields and popular interests.

New Books Network

Religion and Myth in the Marvel Cinematic Universe

Breaking box office records, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has achieved an unparalleled level of success with fans across the world, raising the films to a higher level of narrative: myth. Michael D. Nichols’s Religion and Myth in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (McFarland, 2021) is first book to analyze the Marvel output as modern myth, comparing it to epics, symbols, rituals, and stories from world religious traditions.

Nichols places the exploits of Iron Man, Captain America, Black Panther, and the other stars of the Marvel films alongside the legends of Achilles, Gilgamesh, Arjuna, the Buddha, and many others. It examines their origin stories and rites of passage, the monsters, shadow-selves, and familial conflicts they contend with, and the symbols of death and the battle against it that stalk them at every turn. The films deal with timeless human dilemmas and questions, evoking an enduring sense of adventure and wonder common across world mythic traditions.

New Books Network

Hot Pants and Spandex Suits: Gender Representation in American Superhero Comic

Superman, Batman, Captain America, and Iron Man are names that are often connected to the expansive superhero genre, including the multi-billion-dollar film and television franchises. But these characters are older and have been woven into American popular culture since their inception in the early days of comic books. The history of these comic book heroes are histories that include bulging muscles, flashy fight scenes, four-color panels, and heroic rescues of damsels in distress. Esther De Dauw’s new book,

Hot Pants and Spandex Suits: Gender Representation in American Superhero Comic (Rutgers UP, 2021) analyzes these characters with a critical lens to explore what exactly these figures teach the readers and the public about identity, embodiment, and sexuality. De Dauw, a comics scholar, focuses her research on the intersectionality of race and gender in comic books.

Hot Pants and Spandex Suits takes the audience through the 80-year evolution of comic books to discuss the changes in identity and culture, and explore what these heroes say about and to the American people. As an expert in Comic Studies and Cultural Studies, De Dauw uses theories of structural power relations to explain the disenfranchisement of women, LGBTQIA+, and the Black community in comics. As she notes, superheroes are often metaphors for the concerns of the dominant culture, and are informed by the dominant gender ideology and the American cultural landscape. Hot Pants and Spandex Suits unpacks superhero actions to examine who these heroes are serving, how, and what this has to say about American culture and identity. These questions frame the discussion throughout the book as De Dauw traces the changing perceptions of identity, cultural, and historical shifts through comic books and their many different heroes. A significant avenue of analysis focuses on the fragility of white masculinity, and how the superheroes essentially became an antidote to the cultural sense that white men were “losing” in American society. With a fascinating tour of the history of comic books, De Dauw welcomes both the academic community and comic-book lovers to venture through this analysis to better understand the role of superheroes within our culture and our politics.

New Books Network

Unstable Masks (2020)

In Unstable Masks: Whiteness and American Superhero Comics (Ohio State UP, 2020), Sean Guynes and Martin Lund have assembled more than fifteen chapters that interrogate our thinking about superheroes, especially those written and created in the United States, and how those heroes participate in reifying the whiteness of American politics, culture, and worldview. Even as we have seen attempts to diversify the representation within the superhero genre, there is a continued reinscribing of the normative whiteness that frames not only the narratives themselves, but the ideas and images conveyed by the authors, artists, and producers of these works. As Lund and Guynes note, much analysis has been done about the superheroes, especially paying attention to those heroes who deviate from the norm in terms of race, gender, and sexuality. But what has been missing in a great deal of the scholarship is an analysis of the predominant whiteness of superheroes and how the constructed narrative of the genre, of defeating a threat to a particular way of life, country, people, continues to reaffirm the overarching whiteness of this genre. As Lund noted in conversation, the marquee superheroes are unhyphenated, they are simply the normal, everyday superhero, and they are also, by default, white. Whereas Black, or LatinX superheroes are classified as such, and they are thus distinguished from the “normal” superhero.

It is not only the characters themselves, in the panels, but also the structure of the story that complies with an understanding of whiteness, and a hierarchy that is often racially structured. The superhero is tasked with fighting for the “good” – but who defines that good, and who benefits from that preserved good? This very understanding of the job of the superhero, to fight for “truth, justice, and the American way” builds on the basis that truth is the same for all members of the society, justice is equally distributed, and the American way is quite clear. Except that none of these are accurate depictions of the reality for those living in the United States (or elsewhere). How we discuss the goals that the superheroes pursue is tied into what it is that we anticipate being restored by a superhero who confronts an enemy. The chapters in Unstable Masks explore this dynamic, focusing on the exceptions as well as those who make up the vast majority of this imaginary space, examining how whiteness informs the understanding of the superhero. The contributing authors not only examine different superheroes at different periods, but they also reach back to examine the way that the superhero genre fits within the American cultural and literary tradition of the western, detective fiction, and the conquest of the frontier where individuals imposed “law and order” on “ungoverned” or “unstable” parts of the continent.

New Books Network

American comics from the start have reflected the white supremacist culture out of which they arose. Superheroes and comic books in general are products of whiteness, and both signal and hide its presence. Even when comics creators and publishers sought to advance an antiracist agenda, their attempts were often undermined by a lack of awareness of their own whiteness and the ideological baggage that goes along with it. Even the most celebrated figures of the industry, such as Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Jack Jackson, William Gaines, Stan Lee, Robert Crumb, Will Eisner, and Frank Miller, have not been able to distance themselves from the problematic racism embedded in their narratives despite their intentions or explanations.

In Bandits, Misfits, and Superheroes: Whiteness and Its Borderlands in American Comics and Graphic Novels (University of Mississippi Press, 2022), Dr. Josef Benson and Dr. Doug Singsen provide a sober assessment of these creators and their role in perpetuating racism throughout the history of comics. They identify how whiteness has been defined, transformed, and occasionally undermined over the course of eighty years in comics and in many genres, including westerns, horror, crime, funny animal, underground comix, autobiography, literary fiction, and historical fiction. This exciting and groundbreaking book assesses industry giants, highlights some of the most important episodes in American comic book history, and demonstrates how they relate to one another and form a larger pattern, in unexpected and surprising ways.

New Books Network

GENETIC MUTATIONS AND SUPERPOWERS

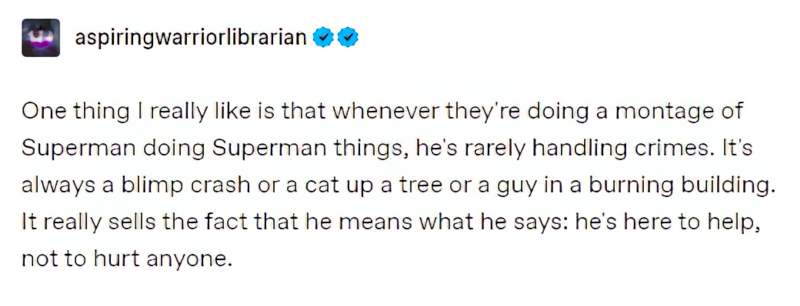

PEOPLE WITH POWER DOING GOOD?

A lot of the appeal of superheroes is “people with power doing good”. That said, Being good” seems to involve a never-ending stream of violence, escalation, and doing absolutely nothing to improve the quality of life in the world around them. Superhero stories cater to the fantasy of people with power doing good even when their actions in the real world would actually cause chaos.

It is not a straightforward American Dream story, because not everyone can be a superhero; you have to be born super.

The F-Word 2005 review of Pixar’s The Incredibles

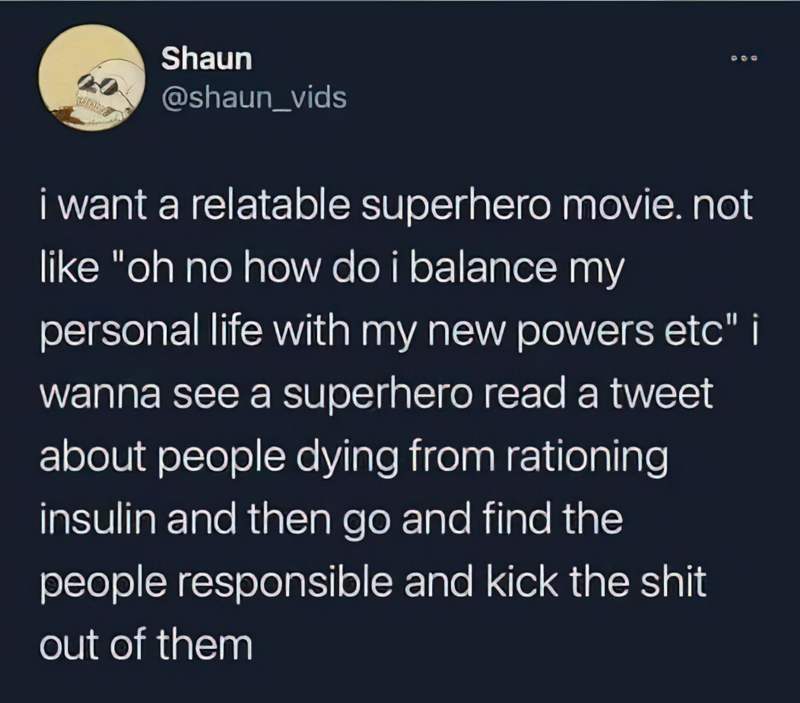

It’s very hard for me to get into superhero or chosen one stories because I find the very concept of “great men” antithetical to everything I believe in. I believe “great man” narratives have been used as a method of control for millennia.

So, for me, the greatest hurdle I have to liking those stories is that I have to be able to find the other elements sufficiently entertaining that the story which I find morally reprehensible can be ignored. Or it has to be a deconstruction.

I look at the trajectory of history, and this idea of the divine individual has been at the root of so many conflicts. Religion. Monarchy. It’s all a symptom of a worldview that fundamentally values the individual over the masses. I’ve heard that story before. I hate it.

The deepest these stories get to me is when they try to tackle morality and responsibility. I don’t think that with great power comes great responsibility-I believe power should be shared among the people with informed consent and popular consensus.

I do not think an individual with sufficient power and moral authority can fix the world; I believe that a world where one person can have that much power is a world that’s already fundamentally broken by virtue of their existence.

I believe that power corrupts, but more importantly I believe that power imbalance is inherently unjust, and something to lament, not to celebrate and trust.

“But Superman at his purest form is a beautiful thing! Truly wholesome and pure!” I fundamentally disagree. I don’t think a lone operator should be allowed to make massively important decisions for the world. I do not believe his value code is morally correct.

I believe that bank robbers should not be caught. I believe in a “justice” that dismantles institutions like banks. The “American Way” he stands for is a lie sold to children to make them grow up loyal to capitalism.

I find these stories to yearn for a status quo. There’s a bad guy, and if you beat him up hard enough, things will go back to normal because you saved the day. I am opposed to “normal.”

There’s the rub, ethically. To me, direct action to end oppression is how you make the world a better place. Toss a bus containing the Fortune 100 off a cliff and you make the world a better place. Objectively. But that’s what VILLAINS do.

I envision a beautiful future. I can look forward to a better world. But the path is not laden with super powerful individuals. It’s with a parade of people hand in hand. I don’t want royalty. Nobility. I want a classless world.

@machineiv

Limitations Of The Superhero Story

Thompson has nothing against superhero movies in theory — “I loved the original Superman with Chris Reeve,” she said, “because there was a real tongue-in-cheek-ness to it” — but their increasing prevalence is a whole other matter. “After a while, you do get a tiny bit cynical about it,” she said. “The fact that I know they’re going to win out in the end has now slightly interfered with my continuing to go to those movies. If I see yet another Spider-Man, I’m going to have to actually hang myself. I can’t do it anymore! They’re all marvellous, but how many times can you make this franchise, for crying out loud?” Still, there’s at least one capes-and-tights movie left that she’s looking forward to: “I’m up for Wonder Woman, totally.”

Emma Thompson

Superheroes and Their Community

[S]uperheroes lose something when they’re not connected to their non-super communities.

My unified theory of superheroes is that they usually start out with a strong supporting cast of ordinary humans, who keep them grounded. Over time all of those side characters get superpowers/secret identities. Eventually every scene is superheroes talking to other superheroes.

@charliejane 2:49pm · 25 Jul 2021

Superheroes as Allegory

A discussion on whether superpowers can legitimately be considered allegories for disability.

Psychiatrists Lauretta Bender and Reginald Lourie describe “comic books as modern folklore, noting that the omnipotent superheroes had their parallels in fairy tales; replacing

magic with science.” (Fingeroth, 2004, p.23)

Subversions Of The Superhero Story

“Have no fear, citizens! Captain Superlative is here to make all troubles disappear!”

Red mask, blue wig, silver swimsuit, rubber gloves, torn tights, high top sneakers and . . . a cape? Who would run through the halls of Deerwood Park Middle School dressed like this? And why?

Janey-quick to stay in the shadows-can’t resist the urge to uncover the truth behind the mask. The answer pulls invisible Janey into the spotlight and leads her to an unexpected friendship with a superhero like no other. Fearless even in the face of school bully extraordinaire, Dagmar Hagen, no good deed is too small for the incomparable Captain Superlative and her new sidekick, Janey.

But superheroes hold secrets and Captain Superlative is no exception. When Janey unearths what’s truly at stake, she’s forced to face her own dark secrets and discover what it truly means to be a hero . . . and a friend.

My name is Flint, but everyone in middle school calls me Squint because I’m losing my vision. I used to play football, but not anymore. I haven’t had a friend in a long time. Thankfully, real friends can see the real you, even when you can’t clearly see.

Flint loves to draw. In fact, he’s furiously trying to finish his comic book so he can be the youngest winner of the “Find a Comic Star” contest. He’s also rushing to finish because he has keratoconus—an eye disease that could eventually make him blind.

McKell is the new girl at school and immediately hangs with the popular kids. Except McKell’s not a fan of the way her friends treat this boy named Squint. He seems nice and really talented. He draws awesome pictures of superheroes. McKell wants to get to know him, but is it worth the risk? What if her friends catch her hanging with the kid who squints all the time?

McKell has a hidden talent of her own but doesn’t share it for fear of being judged. Her terminally ill brother, Danny, challenges McKell to share her love of poetry and songwriting. Flint seems like someone she could trust. Someone who would never laugh at her. Someone who is as good and brave as the superhero in Flint’s comic book named Squint.

Efrén Nava’s Amá is his Superwoman – or Soperwoman, named after the delicious Mexican sopes his mother often prepares. Both Amá and Apá work hard all day to provide for the family, making sure Efrén and his younger siblings Max and Mía feel safe and loved.

But Efrén worries about his parents; although he’s American-born, his parents are undocumented. His worst nightmare comes true one day when Amá doesn’t return from work and is deported across the border to Tijuana, México.

Now more than ever, Efrén must channel his inner Soperboy to help take care of and try to reunite his family.

When thirteen-year-old Joe is left behind in Peckham while his mum flies to Spain on holiday, he decides to treat it as an adventure, and a welcome break from Dean, her latest boyfriend. Joe begins to explore his neighbourhood, making a tentative friendship with Asha, a fellow fugitive hiding out at her grandfather’s flat.

But when the food and money run out, his mum doesn’t come home, and the local thugs catch up with him, Joe realises time is running out too, and makes a decision that will change his life forever.

It begins, as the best superhero stories do, with a tragic accident that has unexpected consequences. The squirrel never saw the vacuum cleaner coming, but self-described cynic Flora Belle Buckman, who has read every issue of the comic book Terrible Things Can Happen to You!, is the just the right person to step in and save him. What neither can predict is that Ulysses (the squirrel) has been born anew, with powers of strength, flight, and misspelled poetry—and that Flora will be changed too, as she discovers the possibility of hope and the promise of a capacious heart.

A laugh-out-loud story filled with eccentric, endearing characters and featuring an exciting new format—a novel interspersed with comic-style graphic sequences and full-page illustrations, all rendered in black-and-white by up-and-coming artist K. G. Campbell.

This is science fiction for children because Ulysses is a squirrel who has been given superpowers by being sucked up into the vacuum cleaner.

The language in this book is complex, and demonstrates wider understanding of literature, for example in the way comic books are not accepted as proper literature. The characters are excellent, as are the friendships.

FURTHER READING

Thor Ragnarok: Why superhero movies only work if they’re funny

Why Theology and Spider-Man? at Popular Culture and Theory