**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

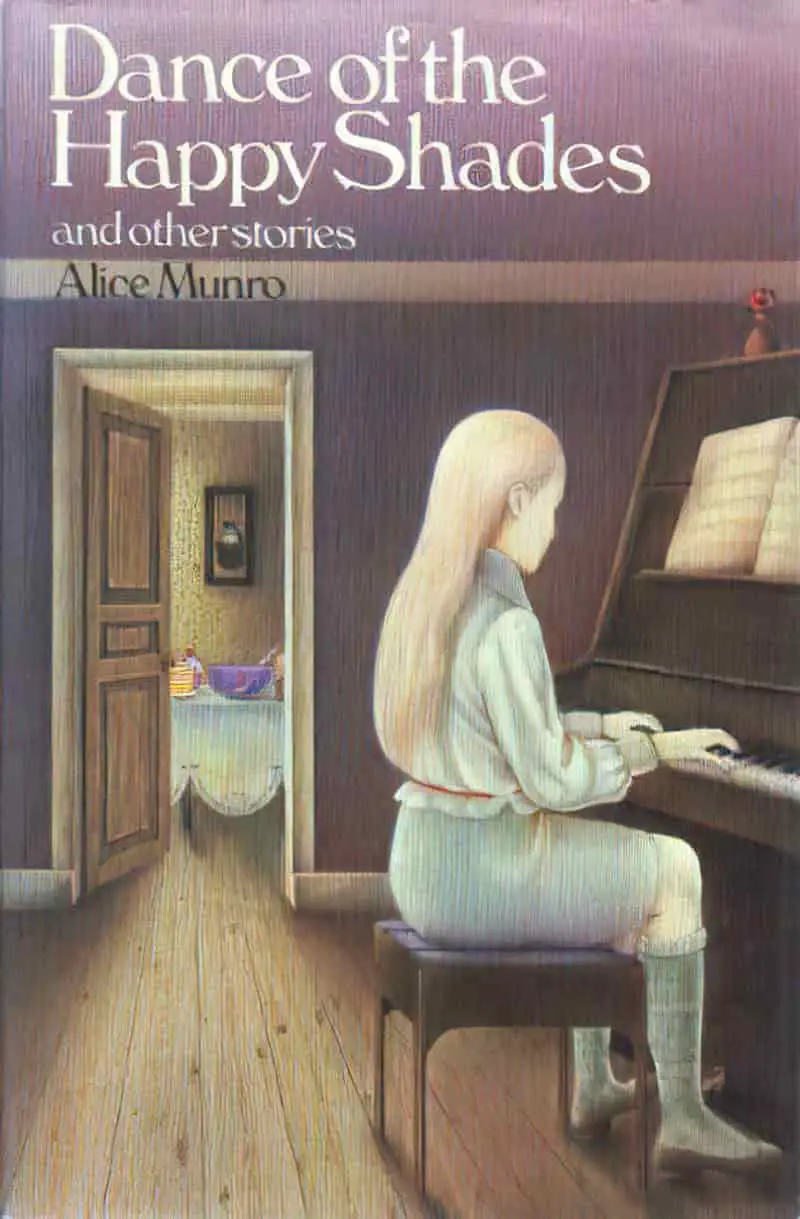

“Sunday Afternoon” is a short story by Alice Munro, included in the 1968 Dance of the Happy Shades collection.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “SUNDAY AFTERNOON”

Readers spend a Sunday afternoon in the home of a wealthy family called the Gannetts who are hosting a gathering of friends. The story is revealed via the viewpoint of their new 17-year-old housemaid, Alva. However, the viewpoint shifts in and out of Alva’s head. Sometimes we see Alva from Mrs Gannet’s point of view.

ALVA THE HOUSEMAID

Alva is a country girl who has been working for the Gannetts for three weeks. She is described as a ‘high school’ girl, but it would seem she has recently left high school, because she has her own room at the Gannetts’, which means she’s the live-in maid.

Today she is helping out with another social gathering. She has replaced a woman called Jean. We can deduce Jean was an older woman with more experience and attention to detail as Jean knew how to carve radishes into little roses, unlike Alva, who is not about that.

Instead, Alva is coming to terms with her role as a member of the servant class, and by the way she considers how her own mother would respond to one of the old maids in her own kitchen, it would seem that Alva is not of an entirely separate class from the Gannetts herself. (In the modern era you can be socially of the same class as someone else but have far less wealth.)

Alva is recently a high schooler, and is not used to her new, deferential role. She deals with this awkwardness by giving short, closed-in answers to Mrs Gannett’s attempts to appear friendly. Today she is also drinking the dregs from the sweetened gin glasses which come back to the kitchen for washing.

She’s wearing a blue uniform, matching the modern 1960s kitchen, and shoes with Cuban heels (a very old style which were popular with 1960s mods). She is also required to wear stockings whereas the women of the house wear sundresses and are dressed for sunbathing.

MRS. GANNETT, LADY OF THE HOUSE

Mrs Gannett has a 1960s rich lady look—we call them leather ladies in Australia. To show she’s a member of the leisure class, she’s gotten a heavy tan, and has now had too much sun for her white lady skin. She is also fashionably slim, which makes her ‘splintery’. However, everything about her says ‘rich’, and whatever the decade, ‘the rich look’ is ‘The Look’. The following sentence could be used in a contemporary story:

Mrs Gannett had a look of being made of entirely synthetic and superior substances.

“Sunday Afternoon”

It is soon revealed that Mrs Gannett has a flirtatious banter going on with a man called Derek Vance, stockbroker.

MRS GANNETT’S FAMILY

It would be easier to understand the introductions on the first page if we were given the last name of Mrs. Gannett’s family. (I had a bit of trouble remembering that Gannett is her married name.

I was also a little confused about the phrase ‘right side’ of the family. Does it mean anything in ancestry lingo? It would seem not. This seems to be Alva’s assessment of who counts as worthwhile, and her assessment of ‘rightness’ is based on who is blonde, slim, athletic and wealthy:

Mrs Gannett’s side of the family was the right side; she had three sisters, all fair, forthright and unreflective women, rather more athletic than she, and these magnificently outspoken and handsome parents, both of them with pure white hair.

“Sunday Afternoon”

Where did Mrs. Gannett’s money come from?

Mrs Gannett’s wealthy father owns an island in Georgian Bay, which is to the right of Lake Huron, marked off by a peninsula. The father has built summer houses for each of his three daughters on this island. (Mrs. Gannett also has a brother who presumably didn’t get a summer house—perhaps he inherits his wealth differently.)

However, the island in Georgian Bay is not where today’s gathering is set. Alva is about to see the island summer house the following weekend for the first time. This house is in a wealthy part of an Ontario suburban town where the houses are set back off the street on large, high-maintenance properties cared for by Chinese gardeners. No one is ever seen in these gardens except for the gardeners. In fact, Alice Munro paints a Stepford Wives sort of setting. The Stepford Wives 2004 film soundtrack would match Alice Munro’s “Sunday Afternoon” perfectly. Meanwhile, the 1975 Stepford Wives film is a decent visual match, with its creepy, Hitchcockian film techniques.

MR. GANNETT

Mrs. Gannett’s husband is peripheral to the story. We hear more about his mother, Mrs. Gannett’s mother-in-law:

The old Mrs. Gannett (Mrs. Garrett’s mother-in-law) is described as a tee-totalling church-led person. Nobody drinks anything but grape juice in front of her. They only start on the alcohol once she shuffles off home. We can deduce that Mr. Gannett likely has no significant inherited wealth:

Mr. Gannett’s mother, on the other hand, lived in half of the red brick house in a treeless street of exactly similar red brick houses, almost downtown.

“Sunday Afternoon”

(I’m assuming Mr. Gannett is a self-made man, though I despise that phrase, as no one is truly self-made.)

EVERYONE GETS A BIT DRUNK

As the afternoon wears on, the house starts to feel ‘unreal’ to Alva, as the adults in the house get more and more liquored up. Alva describes a house in which others get increasingly drunk, though it is clear that Alva, too, is a little tipsy. Alice Munro’s description of the hot house on a slow, drunken Sunday afternoon is wonderfully, perfectly evocative:

Alva would meet people coming from the bathroom, absorbed and melancholy, she would glimpse women in the dim bedrooms swaying towards their reflections in the mirror, very slowly applying their lipstick, and someone would have fallen asleep on the long chesterfield in the den. By this time the drapes would have been drawn across the glass walls of living room and dining room, against the heat of the sun; those long, curtained and carpeted rooms, with their cool colours, seemed floating in an underwater light. Alva found it already hard to remember that the rooms at home, such small rooms, could hold so many things; here were such bland unbroken surfaces, such spaces—a whole long, wide passage empty, except for two tall Danish vases, standing against the farthest wall, carpet, walls and ceiling all done in blue variants of grey; Alva, walking down this hallway, not making any sound, wished for a mirror, or something to bump into; she did not know if she was there or not.

“Sunday Afternoon”

Whenever you come across a house made of vast expanses of glass in fiction, you can pretty much guarantee the people who live inside that house are not happy. Glass, in fiction, indicates emotional coldness, and generally conveys the idea that money cannot buy familial happiness. We see this time and time again storytelling.

MR VANCE, AGAIN

You saw this coming, didn’t you? Mr Vance, stockbroker, is a player. His wife is right there, complimenting the potato salad. He is complimenting the potato salad extra, and is also up close and personal with the seventeen-year-old housemaid who couldn’t easily escape the kitchen even if she wanted to. The power differential is huge.

He stood right behind Alva at the sink, so very close she felt his breath and sense the position of his hands; he did not quite touch her. Mr. Vance was very big, curly-haired, high-coloured; his hair was grey, and Alva found him alarming, because he was the sort of man she was used to being respectful to.

“Sunday Afternoon”

Yet Alva likes his wife more than she likes the other women. Despite being a stockbroker, she feels the Vances aren’t as wealthy as the others.

FREE TIME FOR ALVA

Alva has a bit of free time between clearing up after ‘dinner’ (lunch) and preparing for the next meal, which will be late. So she makes her way to a place in the house where she can read books from the Gannetts’ shelf. In the hallway she encounters Mr Gannett. The reader meets him for the first time. He is a serious man who feels a sense of care for Alva, asking her in his repetitive way if she’s had enough to eat.

However, Alva does not appreciate this kind of attention. She already feels herself to be too fat (and pale) to belong to this wealthy elite, so she takes his concern to heart:

It seemed that he felt a responsibility for her, when he saw her in his house; the important thing seemed to be, that she should be well fed. Alva reassured him, flushing with annoyance; was she a heifer?

“Sunday Afternoon”

Ahhhh-urgh. At this point I start saying, no no nooo, Alva! That is not what that means! However, this is an entirely understandable response given the reality (which continues into the present) that women are discouraged from eating their fill.

LIKE WATCHING A TRAIN CRASH

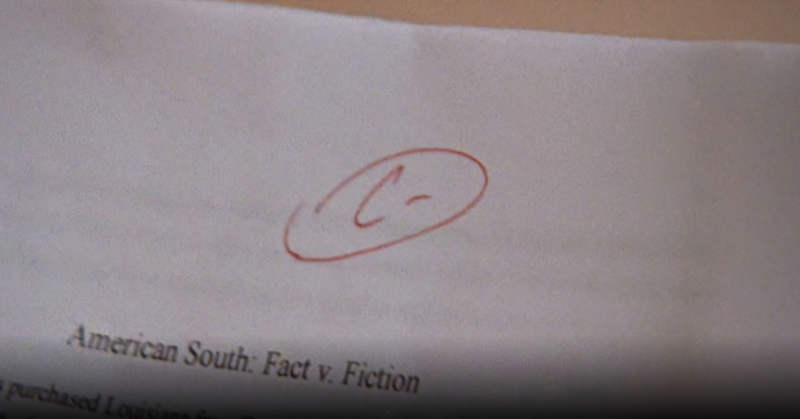

I’m having some feelings. This is how I felt watching young good-looking Julie Taylor get played by her university lecturer S05E03 of American TV drama Friday Night Lights (“The Right Hand of the Father”).

- Julie is away from home and feeling lonely, but also feeling distant from her parents.

- A young, good-looking lecturer shows interest in her. Tells her she’s smart.

- Then he negs her by giving her a C- on her essay, knowing she’ll have tried really hard to do her best, to live up to his professed assessment of her intelligence.

- He tells the class (meaning Julie, the prettiest girl in the class) that if anyone has a problem with their grade, they should go and see him.

- Which is exactly what Julie does. What did she do wrong? Well, she can do better, that’s all. He knows she can do better. He sees something in her.

- He invites her along to a gathering of academics where he knows she won’t fit in. There, he comes onto her properly, confiding in the young first year that although he is married, he isn’t happily married. (Older women everywhere will be yelling at the TV.)

- Feeling special to be entrusted with private information about her handsome lecturer’s personal affairs, Julie takes the opportunity to kiss him. (Everything he has done thus far has invited it.)

- Julie goes home to bed with him, wakes up feeling awkward and sneaks out of his house.

- The following day, he finds her in the cafeteria, tells her it should never have happened, he’s her teacher after all.

Captain Awkward has a great phrase to describe Julie’s position: she’s serving as his “breakup doula“. Captain Awkward also says:

men who love to talk about their hopes and dreams with an attractive new person while keeping their existing relationship are not exactly rare in the universe, and it’s healthy to be very, very skeptical of them.

Help, I’m falling in love with a non-single man!

In a chapter entitled “On Not Sleeping With Your Students”, Amia Srinivasan writes:

Where a student’s desire is inchoate—Do I want to be like him or to have him?—it is all too easy for the teacher to steer it in the second direction.

The Right to Sex by Amia Srinivasan (2021)

This episode of Friday Night Lights placed mature viewers in audience superior position by watching an old dynamic play out once more. I summarise it because this plot line is similar to what Alice Munro is doing here with young Alva. Munro is showing us a fish-out-of-water young woman who is new to her environment, lacking in self-confidence, and insufficiently experienced in the world to know the difference between a man with fatherly intentions and a man with conquest intentions.

Either that, or she knows exactly the difference. Rather, her lack of self-worth could be leading her to the man who objectifies her and uses his social power over her.

The Friday Night Lights episode makes for an especially nice comparison to Alice Munro’s “Sunday Afternoon”, because while Julie is away at college falling into a very old trap, her mature and worldly guidance counsellor mother is back home trying to persuade one of her charges to think about what she’s doing with her body. The girl in question knows exactly what she’s doing with boys, jeopardising her reputation in a conservative town, and continues to do it anyway. These Friday Night Lights storylines juxtapose in a way which asks the audience to consider the morality of each young woman. Who is really worse off, in this instance? The well-intentioned Good Girl, or the designated Bad Girl? Both are being ‘used’; only one of them fully knew it, feeling herself to have agency because she’s doing the using equally.

Anyway, let’s see what will happen to Alice Munro’s Alva, a vulnerable seventeen-year-old fresh out of high school in a house full of drunkards and the lecherous stockbroker, Mr Vance.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE BOOKSHELF SCENE

In the library, Mr. Gannett helps Alva to choose some books.

A man would be more impressed by King Lear than a woman. Nothing could make any difference to Mrs. Gannett; a maid was a maid.

“Sunday Afternoon”

It is unclear who is making this observation. Is it an unseen narrator? Or is it Alva’s understanding? Munro makes use of close third person narration as well as intrusive narration, as her stories see fit. In any case, this story shows readers how a maid’s relationship to the woman of the house is qualitatively different to her relationship with the man of the house. For men, the maid is a sexual being first and foremost. If not sexual, then a daughter-like figure. Nubile womanhood before personhood. In our culture of hypergamy (in which women marry up—to a man who is older, richer, more educated etc.) the fact that a seventeen-year-old girl is a maid is no impediment to a man’s sexual interest in her. Any class distinction doesn’t matter, at least not in the way it matters to another woman.

ALVA’S LETTER

Until now, the narration has been somewhat detached, which matches the scene exactly: The camera floats like a fish around the house which is, likewise, described as if it’s underwater with its blues and greys and languid atmosphere. Also in an underwater scene big fish eat little ones, which adds to the ominous vibe.

But with Alva’s letter home, Alice Munro lets us fully into the head of the seventeen-year-old. There, we achieve a measure of insight regarding what she appreciates in men. Here’s what Alva has to say about them:

I think the men are rather sappy, the fuss they make over perfect lawns and things like that. They do go out and rough it every once in a while but that is all very complicated and everything has to be just so. It is like that with everything they do and everywhere they go.

“Sunday Afternoon”

Alva is hardly going to reveal in a letter home what her sexual preferences are, but it’s very clear to readers from her use of ‘sappy’ that she has an idea of how a Real Man behaves, and he is not someone who is careful (or caring in general).

Straight women who are only attracted to Manly Men are the most vulnerable of all. We see another example of such a young woman in Season Two of White Lotus.

Employed as a ‘personal assistant’ to a mega-wealthy woman with the same misjudgement in men, Portia of White Lotus puts herself in danger by rejecting the clean-cut feminist man in favour of the rough-talking sexually aggressive young man. We know from her expressed dismissal of the “non-binary” romantic options from her home city of San Francisco that she is in the market for a Manly Man (TM), but ultimately Portia can only save herself by moving past her strongly binary gendered requirements.

Back to Munro’s “Sunday Afternoon”. What else do we learn about Alva from her letter?

- Alva insists she’s not lonely, which suggests the lady doth protest too much.

- She does not consider herself a maid. She is merely working as a maid for the summer, and it’s likely she’d like to marry into a family like this one. That is still theoretically possible for her, even if it’s not realistic.

- She’s uneasy around Mrs. Gannett who, as another woman who has lived in the world, might otherwise be young Alva’s strongest ally and protector.

ENTER: MARGARET

Turns out the Gannetts have a thirteen-year-old daughter who has been holed up in her bedroom this whole time packing for next weekend’s trip to the island summer house.

The younger girl asks Alva for romantic advice. Should she start to ‘neck’ this summer?

“Yes,” said Alva. “I would,” she added, almost vindictively.

“Sunday Afternoon”

This sets up the ending of Munro’s story (which is not the end of Alva’s story). The use of the adjective “vindictively” exemplifies how Alice Munro typically deploys adjectives: in unexpected and very telling ways.

BACK TO WORK

Mrs Gannett finds Alva and gently reminds her to get to work washing glassware before preparing dinner.

BLUE SYMBOLISM?

Readers learn that Alva is one girl in a long line of ‘girls’. Why have the others left? Is this some kind of metaphorical “Bluebeard” situation? Wait, is this also why the décor is blue? This would explain Munro’s emphasis on the long, blue corridor and the doors leading off it, some open, some shut ‘softly’ (as if beckoning her in). Bluebeard’s fairy tale castle is labyrinthine. Terrifyingly so.

THE KISS

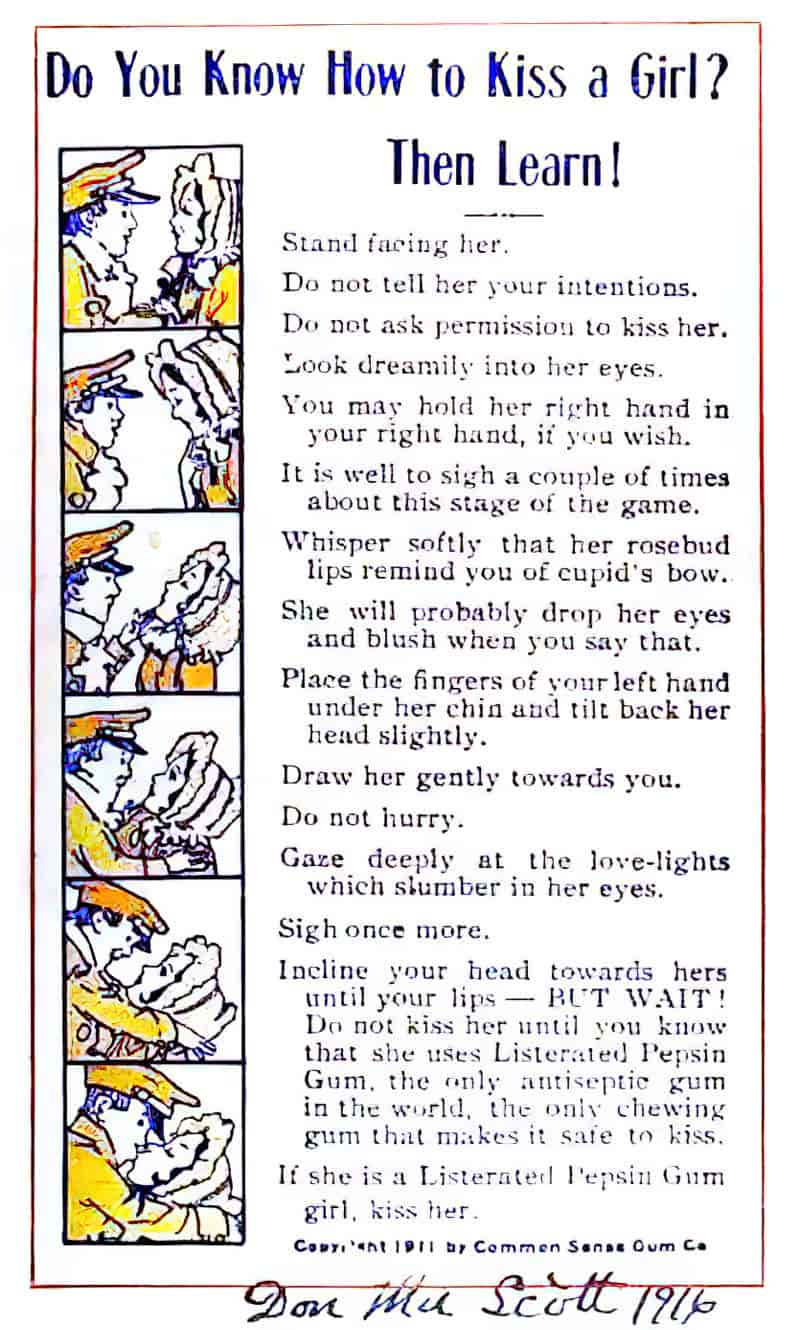

Now a character who has been peripheral at best—some Gannett cousin-or-other—comes into the kitchen, says just enough to impress upon Alva his superior status and then, without asking or waiting for approval, ‘as in a familiar game’ he ‘spend[s] some time kissing her’.

For those of us who live in the post #MeToo era this is a cringey scene.

Alice Munro has pulled a bit of a swifty. We expected Mr Vance to do this, didn’t we? But no, it’s the other guy, whose name she doesn’t know.

What’s more, she likes to be kissed in this way. That is not so unexpected, because Alice Munro has set us up:

- Alva likes a man who takes charge

- She feels removed and almost disembodied as a peripheral person herself, and to be kissed at length is such an embodied, carnal experience, this man (also peripheral) brings her right into the moment. (I’ve heard trauma specialists use the word ‘depersonalisation’ to describe an out-of-body or out-of-touch-with-your-body experience. I’m not sure which is the better term here, but depersonalisation can also mean divesting someone of their humanity and I don’t mean that.)

- For this moment, she can imagine she is one of the Gannetts herself, owning an entire island where everything she sees in every direction is hers.

- She feels desirable, even though she does not feel attractive in comparison to the Rich Ladies around her. (She is pale, not fashionably tanned, and thicker around the waist than she would like.)

So it makes perfect sense that Alva enjoys this kiss, though no one asked explicitly (or implicitly) for consent, and this cousin-or-whoever is very much making use of his status to do as he pleases. Would he have done this even if Alva didn’t happen to enjoy it?

“Say thanks,” Mrs. Gannett’s cousin said, and Alva turned around wiping her hands on her apron, surprised, and then in a very short time not surprised.

“Sunday Afternoon”

Munro’s description of the kiss scene suggests the cousin waited to see consent on Alva’s face before proceeding. But I put it to you that Alva’s enjoyment is irrelevant.

I also put it to you that Alva’s desires are inchoate: Like Julie in Friday Night Lights, who sleeps with her university teacher, does Alva want this man, or does she want the lifestyle he enjoys? Due to the power discrepancy and Alva’s hopeful youth, it will be very easy for him to steer Alva in the direction that suits his temporary desires.

In this particular case Alva was lucky; if the day played out again, roll the dice and her kitchen kisser could easily have been the unattractive and slightly scary Mr Vance.

WHAT TO MAKE OF THE FINAL SENTENCE?

But things always came together; there was something she would not explore yet—a tender spot, a new and still mysterious humiliation.

“Sunday Afternoon”

Though we are assured Alva enjoyed the kiss, which part did she enjoy? She enjoyed:

- the stranger’s touch which eases her

- the gratitude of her body

- a new lightness

- a new confidence (someone has noticed her!)

- the feeling that things are no longer ‘unreal’

- the opportunity to see her world in a new, sunnier light

So what of the ‘still mysterious humiliation’?

Think back to the Friday Night Lights episode in which Julie Taylor’s university teacher plays her like a fiddle. If the episode had stopped right after they kissed, Julie would have been left feeling happy, worthy, on cloud nine.

This is where Alice Munro has chosen to leave “Sunday Afternoon”, because we can figure out for ourselves how it ends.

My take: The cousin will go to the Island, seduce the new maid. Mrs Gannett will definitely know about this; she has shown herself to be savvy enough to know exactly where to find Alva when she’s supposed to be washing glassware (in her daughter’s bedroom). Alva will quietly get the sack, and leave under a cloud just like the many other maids which Munro has been sure to mention. Such is the ‘mysterious humiliation’, which this entire short story serves to foreshadow. The naïve Alva cannot predict the plot of next weeks’ Island Holiday, but still she intuits what’s coming to her. She feels sucked into a tunnel, as she’s been sucked into this fantasy house, with its blue labyrinths and temptations of wealth.

ISLAND SYMBOLISM

After reading, the significance of that off-the-page island becomes clear. Islands in storytelling symbolise many things. (See also: “Cortes Island” by Alice Munro.)

Islands in “Sunday Afternoon”:

- Alva’s isolation. She is isolated from her family, isolated from the lady of the house, isolated in the kitchen, isolated in this big fancy house set back from the road where the neighbours are a good distance away. Her own room is above the garage, isolated from the rest of the house. She is not part of this family, but almost feels like she should be. Mrs Gannett seems to want her to feel part of the family even though she is clearly not—an uncomfortably ambiguous position to be in. Hence, Alva is having difficulty knowing what she is and is not expected to do. As ‘part of the family’ she takes a big sister role when talking to the thirteen-year-old Gannett daughter in her bedroom, yet her sisterly talk is cut short when Mrs Gannett comes to rope her back into the kitchen. And how much of next weekend’s island holiday will be holiday, how much work? In fact, Alva is already on an island. This house is an island. Islands are, by their definition, separate from the land-mass termed the ‘mainland’. Codes of behaviour acceptable on an island can be viewed as ‘outside’ the norm. This results in a different kind of community and different attitudes about in-group and out-group individuals. In this wealthy house where everyone is a bit drunk, a kitchen kiss felt acceptable.

- Alva’s loneliness. Isolation doesn’t always equal loneliness, so it’s worth listing this separately. Alva’s insistence in her letter home (twice) that she is not lonely has the opposite effect. Also, readers see Alva being lonely. She must resist not joining in on the happy vibe of the house. She must remember not to look through a door when she hears a happy sound. That’s not what she’s here for.

- The mysteriousness of the final sentence: Usually seen from afar, islands garner all sorts of mythology around them. This can be seen in ancient myth and fairy tale.

- Islands in fiction are often depicted as liminal sites. (Liminal = relating to a transitional or initial stage of a process.) Alva is at a liminal period of her life. She has just finished her schooling and now she has been thrown fresh into a new social milieu. We see her discomfort as she tries to navigate her new role and the ambiguous unspoken rules.

- Islands are classic locales of romance: We can therefore interpolate that romance (or a synthetic replica of it) will happen next weekend between the cousin and Alva.

- On islands in children’s stories, the division between fantasy and reality is frequently erased. Still partly a child herself, Alva may be having difficulty distinguishing between true romantic interest and the sexual opportunity of a stranger.

Sundays In Art And Illustration

DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES (1968)

- “Walker Brothers Cowboy” — A woman looks back at her 1930s childhood. Her family has 2 or 3 months earlier lost the family fox farm and moved to a small town on the edge of Lake Huron, where the father has started a new job as a door-to-door salesman. Meanwhile, the mother sinks into a depressive state. One day, the father takes the narrator and her younger brother on a ride, where he visits an old friend/lover. The daughter learns that her father had another sort of life once.

- “The Shining Houses” — In a new neighbourhood, many houses have been built next to an old one. The owner of the older house, Mrs. Fullerton, does not take care of her property to the extent that the owners of the new houses would like. They conspire to get rid of the old poultry-farming witch. Only our narrator seems conflicted.

- “Images” — A little girl is the narrator of this double character study: A second cousin who came to take care of the household while her own mother was sick, and a man with a psychotic mental illness who lived alone in the woods. After meeting the man in the woods, the little girl learns not to be afraid of the woman who has infiltrated the household to take care of them all.

- “Thanks for the Ride” — This story is written with the viewpoint character of a young man. He has just finished school and is out with his older cousin with the purpose of losing his virginity. Together they pick up some ‘loose’ girls. The whole experience is perfunctory and defamiliarizing.

- “The Office” — A housewife decides to improve her life by carving out some time for herself to pursue her passion of writing. So she rents a room above a hair salon and drugstore. But the landlord won’t leave her in peace, deeming her time his.

- “An Ounce of Cure” — A young teenager is pining after a boy who dumped her months ago for another girl. She can barely think of anything else. One night she is babysitting when she spies three bottles of liquor on the bench. She accidentally gets very drunk and very caught out. Her reputation is ruined. But as an older woman looking back on this time, she is glad it happened.

- “The Time of Death” — A mother who lives in one of the squalid cottages on the edge of town has lost a child in a terrible accident. The village gathers round, but how genuine are they in their grief?

- “Day of the Butterfly” — Two girls at a primary school are ostracised. One is the narrator, now grown, ostracised for being an out-of-towner who doesn’t wear the right clothes. The other is more ostracised still, because her parents are immigrants, because she smells like rotting fruit, and because her brother needs her to accompany him to the toilet. When this girl is dying in hospital from child leukemia, the young narrator is filled with inexplicable grief. It is now too late to be a real friend to this outcast, and anything she does in kindness will feel empty and pointless.

- “Boys and Girls” — An outdoorsy farm girl loves helping her father on the fox farm but realises she’ll very soon be required to go indoors to help her mother with domestic work. In contrast, her younger brother, far less conscientious, will be allowed to stay outside and work with the animals, enfolded and welcomed into the masculine world.

- “Postcard” — A woman around the age of 30 has been seeing a man for years. They’re long-term partners. The reason they haven’t married: He’s waiting for his mother to die. His mother wouldn’t approve of him marrying the narrator, we deduce because of the wealth disparity. Unfortunately for the narrator (Helen), turns out the guy never intended to marry her anyway. He sends her a postcard from Florida telling her how he’s having such a good time. Next minute, Helen’s best friend is round to break the bad news: It’s been published in the paper, the lover is getting married to someone else after all this time. The weasel didn’t have the gumption to let Helen know. So she goes round to his house, stands outside and expresses her grief in a very vocal way.

- “Red Dress—1946” — A thirteen-year-old girl’s first ball. Her mother sews a red dress with a princess neckline. Suddenly she looks much older. She barely recognises herself in the mirror, and longs for childhood again. Almost all the girls around her are obsessively interested in boys. Everyone, that is, except one other girl who says she despises boys, and plans to support herself by working as a P.E. teacher. But by aligning herself with this queer girl, our thirteen-year-old risks much. What will she do? Will she take up the offer of friendship?

- “Sunday Afternoon“

- “A Trip to the Coast” — An eleven-year-old girl called May lives with her mother and grandmother (mostly her grandmother) in a general store in a three-house township. There’s nothing to do in this one horse town. But today she’s looking forward to same-age company. However, the “company” is a total let-down, and so her grandmother, for the first time ever, suggests the two of them take a trip to the coast. But then another visitor comes. A customer who declares himself an amateur hypnotist. This story ends on a cliff hanger, and I don’t believe Munro has given us enough of a symbolic layer to fill in the gaps for ourselves. I believe we’re supposed to feel exactly as unmoored as eleven-year-old May, waiting out front of the store in the rain.

- “The Peace of Utrecht” — Numerous critics and scholars consider this story the jewel of the crown of Munro’s first collection. Considering that, it’s baffling why it doesn’t make it into more Selected and Collection volumes. It’s certainly the most overtly personal of Munro’s early stories, and she has said in interview that this one changed the way she wrote. Until writing “The Peace of Utrecht” she’d written to be a writer. Now she wrote because she knew only she could write this story. The biographical relevancy: young Alice Munro cared for her mother over many years as her mother lived, then died, with Parkinson’s disease.

- “Dance of the Happy Shades” — An emotionally astute and very observant adolescent girl is required to accompany her mother to an embarrassing recital with the elderly, unfortunate-looking spinster teacher whose spinster sister is recently bedridden due to a stroke. The story is told via the slightly baffled viewpoint of the girl, who is required to recite a tune on the piano at these excruciating annual events.