Strays Like Us is a 1998 middle grade novel by American author Richard Peck. (155 pages)

Peck not only understands the fragile emotions of adolescents, he also knows what kind of characters will pique their interest. In this tender novel, he paints a richly detailed portrait of Molly, a drug-addict’s daughter sent at the age of 12 to live with a great-aunt she has never met. Molly soon discovers others like her in this small town full of secrets.

Publisher’s Weekly starred review

SETTING OF STRAYS LIKE US

Strays Like Us is set in The (American) South but is not a Southern Novel as such. This is one of those American stories which could easily be set elsewhere — like lots of ‘midwestern’ stories set in suburbia or small towns. Molly’s story could belong to many kids all over.

This one happens to take place in small town Missouri. The ‘small’ town is significant because of the way gossip works:

“How did the guys find out anyway?”

“Becasue they don’t let you keep a secret in a town like this.”

Although this is like a 1950s utopia in some ways, there is a lot of poverty in this town and turns out to be an snail under the leaf setting. Richard Peck is making a statement about income inequality when he writes:

“There’s things they can do now for what Fred had,” [Aunt Fay] said finally. “But he didn’t have insurance.”

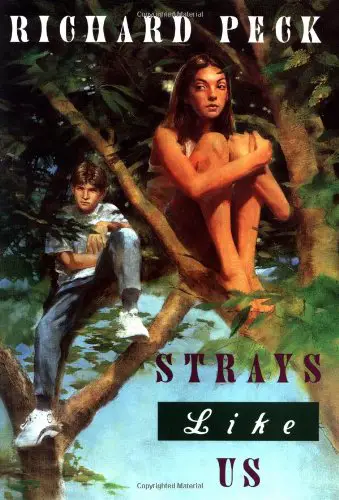

The story opens with Molly up a tree. She is in semi-hiding up here, melding with nature, and although in reality trees are reliant on each other via their root system, the common understanding of tree symbolism is that they stand ‘tall, proud and alone’, like Molly at the beginning of her character arc.

Molly Moberly in the foreground with neighbour Will in the background.

Molly Moberly knows she doesn’t belong in this small Missouri town with her great-aunt Fay. It’s just a temporary arrangement–until her mother gets out of the hospital. But then Molly meets Will, a fellow stray, and begins to realize she’s not the only one on the outside. In fact, it seems like the town’s full of strays–only some end up where they belong sooner than others. Richard Peck has created a rich, compassionate story that will go straight to the heart of every kid who’s ever felt like an outsider.”This sensitive heroine is one readers will want to take under their wing.” —Publishers Weekly, starred review

The exact year of this story is unclear — there is mention of computers and microwaves so I believe it is set in the late 1990s, at time of publication. Still, there is a 1950s feel about it. Locals are starting to feel suspicious of strangers, because until this period everyone has known everyone here.

The 1990s was the era of peak fear when it came to AIDS. We heard about it a lot — it was feared in the West unlike anything else, mostly associated with gay sex and illegal drug use and therefore highly stigmatised. Young readers today probably haven’t encountered that attitude in their own milieu, as AIDS has largely left public consciousness in the West, replaced by other fears such as the odd ebola outbreak, or mosquito borne encephalitis.

More clear than the exact year of the setting is the month of each incident. The reader is grounded in time with consistent reference to the month, the holiday event (be it Thanksgiving, Christmas or the beginning of the school year/start of a new one) and the season (whether Molly can hear bees or not and so on). Reference to season is more common in stories for and starring girls.

Spring came in a hurry here, before I knew it. The wind softened, and I felt the year revolving under my feet. Bare branches began to bud, and I remembered the heavy green shade of the trees, last summer when I’d come.

Nature also tends to be important in feminine stories, connected inextricably to the seasons in most ‘storybook’ parts of the world. Richard Peck manages to convey the ‘apparentness’ of this snail under the leaf setting by adding ‘fake grass’:

We stood in a little know beside a patch of fake grass where the casket rested. There weren’t any flowers. Mrs McKinney and Aunt Fay looked smaller than they were, hunched in their winter coats.

Richard Peck also uses a technique which makes any social situation more interesting — he abuts rich and poor people together, linking them inextricably. Molly herself is genetically related to a rich woman, but her whole life she’s lived in poverty. This is a version of a Cinderella rags-to-riches tale. Mrs Voorhees, bed-ridden and hypochondriac despite having married into riches after her first husband died in the grain elevator, shows that money can’t buy happiness — the modern take on the rags-to-riches story.

REVEALS IN THE NARRATIVE OF STRAYS LIKE US

Contains spoilers, of course.

Strays Like Us is a masterclass in drip-feeding information. In a quiet story like this one, these reveals provide the necessary reasons to keep reading.

- Molly’s mother is a drug addict

- Who is in hospital

- And who has checked herself out back in October even though it is now Christmas

- Will’s father is not in prison after all, he’s cooped up inside Will’s house with pneumonia

- Which turns out to be AIDS

- The homeschooled girl Molly meets at the library seems to have the perfect family situation but engages in criminal behaviour when she sets fire to the school

- And is badly burned

- In chapter 14, the wealthy, lonely woman Molly visits turns out to be her grandmother

- Chapter 14 also gives readers and Molly the true extent of her mother’s terribleness. She is trying to use her status as a ‘mother’ to prevent a stint in jail for dealing in dope.

These reveals are in most cases based on lies told to other people, half-truths told to save feelings and stories told to comfort oneself. A lot of middle grade stories ask readers to consider the function of lies versus truth, and this is a good example.

The revelation that Will really does have a father turns out to be a bit of a ‘reversal’ so far as Molly’s concerned. She thought she was like him, but now she realises she’s alone in her predicament. This is possibly the worst thing that Molly can hear right now, just as it’s clear her own mother is not on her way to collect her and in fact has gone AWOL. This is how Richard Peck puts his main character through her paces, doing the worst to her but within the confines of a safe environment.

STORY STRUCTURE OF STRAYS LIKE US

NARRATION AND VIEWPOINT OF STRAYS LIKE US

Written in first person, Molly Moberly looks back to an earlier time in her life. At the time of ‘writing’, she is older and wiser. We are constantly reminded that this is written by an older person looking back. As a narrator, the older Molly is able to hint at differences between what is ‘true’ and what is ‘perceived’ by herself at the time. She is also able to tantalisingly foreshadow the reveals by telling the reader that there are secrets about this snail under the leaf setting waiting to be uncovered.

Will wouldn’t have to pay because of what happened to his dad. That’s what I thought because that’s what I wanted to think.

The Kirkus reviewer describes this form of narration as ‘abrupt and somewhat detached’ and also ‘wistful’ and ‘ingenuous’, showing that when it comes to picking your narrative technique, you simply cannot please everyone. However, Kirkus does admit that the narration ‘gains strength’ as the story progresses.

What do you think?

SHORTCOMING

I’ve done no study on this, but it feels like alliterative names are more common in children’s literature, as well as in light-hearted genre fiction for adults. Molly Moberly, Missouri. This story has dark themes and Molly’s alliterative name — in a very small way — helps remind us somehow that this is a children’s story. Molly’s isn’t the only alliterative name; we also have Brandi Braithwaite and Rocky Roberts.

PSYCHOLOGICAL SHORTCOMING

Molly Moberly has a ‘ghost’ which is revealed to the reader in drips and drabs but quite early on. She has been sent to a new foster home in yet another town because her drug-addicted mother is unable to care for her. Molly needs to find a parental figure. She also needs to let go of her biological mother ever fulfilling that role for her.

MORAL SHORTCOMING

Because Molly is scared of rejection, she is disinclined to make friends, ostensibly because she figures she won’t be sticking around long enough to bother making any. When Will from next door introduces himself she treats him badly by rejecting his offer of friendship and hoping he’ll roll off the roof.

DESIRE

Molly has no wish other than to keep her head down, out of trouble, with her new life on hold waiting for her mother to come and get her.

More deeply, she wishes for stability and family.

OPPONENTS AND ALLIES

Will McKinney is a fake-opponent ally. He is in a similar situation to Molly — with precarious family circumstances and a lot going on.

Other opponents are well-meaning, as opponents often can be. Mrs Pringle, the well-meaning full-time mother who gives Molly a pile of clothes is trying to help, but ends up potentially damaging Molly’s sense of self-sufficiency by treating her as a charity case.

Aunt Fay is a true ally, understanding Molly’s emotional needs and giving good advice. Aunt Fay is the motherly figure Molly needs. Aunt Fay is well-developed as a character. When Will’s father dies we are given the hint of an existential crisis when she looks away out her side window at the tombstones and laments her own capacity for keeping the man alive or being able to keep him comfortable.

The cast of demented and sick people in Aunt Fay’s life make for a cast of eccentric and crotchety characters, alternately grateful and annoyed by Molly’s existence. These characters are not fleshed out — we don’t get to know their motivations. They function mostly as thumbnail sketches within Molly’s journey.

Rocky Roberts is a misunderstood villain. Like the disfigured man in Wolf Hollow, he is the handy scapegoat for bad things that happen in this small town.

Nelson Washburn stands for people who cast judgment over others without scrutinising the facts. Brandi Braithwaite, a caricature of a snarky adolescent girl, goes one step further and full-on makes up a story about seeing Rocky Roberts with a can of petrol on the night of the arson. These characters are opponents of ‘the truth’, which is what Aunt Fay stands for, and what her great niece Molly strives towards.

PLAN

In a post-Pollyanna kind of way, Molly learns to care for herself by first caring for others, looking outside her own situation to see that others have their own problems, even when it appears they are living in a kind of utopia. This is Aunt Fay’s plan, no doubt, rather than Molly’s own idea. But usually in these stories, where a ‘plan’ has been foisted upon them by someone else, about halfway through the main character will switch from being extrinsically to intrinsically motivated. When Molly plays cards with Mrs Voorhees we know she’s switched her mindset. Nobody told her she had to do it — she sees Aunt Fay caring for others and takes her lead.

BIG STRUGGLE

Aunt Fay models a necessary but uncomfortable confrontation about boundaries by having it out with hypochondriac Edith Voorhees who is sapping too much of her time and emotional energy. This marks the beginning of Molly’s anagnorisis — that things are always in flux:

Why couldn’t [Aunt Fay] go back to being the way she’d been, getting sassed by Mrs. Voorhees and sassing her back? Why did things have to keep changing, even here?

Next, Aunt Fay has another uncomfortable conversation with the coach when he brings in an injured Will, in a town where people are worried about the blood of the son of the man who just died from AIDS.

“Then talk plain. I do.”

In this way, Aunt Fay is modelling the telling of truth.

Next it’s Molly’s turn to have a big struggle of her own. Chapter 13 (a symbolic number?) describes the conflagration at the high school. This is the outer ‘big struggle’ which symbolises Molly’s internal growth. At the beginning of this chapter she is still keeping her ‘Debbie notebook around’ — though she’s only using the blank pages to keep notes about school, not to write fiction about her mother. The pace quickens as Aunt Fay is challenged with the task of getting Tracy Pringle’s mother to call the ambulance, with the ticking-clock of a badly burned child. Waiting downstairs, Molly realises that this big house is ‘too empty’. It dawns on her that Tracy doesn’t have a father (and that she is therefore not the only ‘stray’). The Pringles’ house appeared at first glance to be a warm house but is in fact cold and unwelcoming.

ANAGNORISIS

This is a story about found family, popular in middle grade stories. The message is, “You need to start finding your own people, because those you got lumped with by circumstance aren’t necessarily the best people for you.”

Strays Like Us makes use of the ‘Magical Age Of 12′ principle, in which Molly Moberly is 12 at the beginning of the story, turns 13 partway through it, and this maps exactly with her character arc from ‘naively hopeful’ to ‘realistic and rational’. In tandem, Will goes through the masculine version of coming-of-age, growing tall with a thicker neck and bigger muscles, especially after he loses his father and his grandfather mistakes him for father.

NEW SITUATION

If you do not have a happy ending for the young, you had better do some fast talking.

Richard Peck

The story ends when Molly is 13 and a half. She’s growing out of childhood pastimes that require getting her hands dirty. The story has followed the course of one full year and the final scene places Molly back up the leafy tree from the opening scene, creating circularity and the sense of an ending.

Something’s happened to summer. It melted away before we knew it.

Summer is of course a metaphor for childhood. The seasonal emphasis in this story has marked Molly’s trials in her journey from childhood to adolescent.

Molly gives the social worker her precious Debbie notebook, no longer precious. She wants Debbie to have it if it gets to her, which is the outer reason for her getting rid of it, but at a psychological level she is letting go of the idea that her birth mother will ever be her real mother.

It is rare to find an out-and-out evil mother in children’s literature, though this one comes close at one point. Peck doesn’t break the final taboo — that in which a child really doesn’t feel anything at all for her mother:

I loved my mother, and she loved me. She loved me like a rag doll you drag around and then leave out in the rain. I still love her, but I live here.

This middle grade novel offers no neat solution to the social issues presented. This may or may not feel satisfying, depending on what the reader needs from a novel:

The novel settles upon a host of difficult issues and then, indescribably, lets them go: When Will sustains a bloody injury while playing ball, the coach requests that he quit the team because other members are afraid of contracting HIV. Instead of countering this ignorance, Will retreats, and the issue is dropped, with only a few utterances of protest from Aunt Fay. The novel becomes something of a treatise about a generation of children who have been cast aside by their parents; with its compelling premises and Molly’s fragile but tautly convincing voice, it will be seized upon by Peck’s fans, but may leave them longing for more.

Kirkus