“Strawberry Spring” is a short “Jack the Ripper” story by American writer Stephen King. But rather than Jack the Ripper, King utilises Victorian folklore around a figure known as Springheel Jack.

Find the story, with an audio recording, here.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS FOR “STRAWBERRY SPRING” BY STEPHEN KING

Be sure to read the story before reading these questions. Spoilers abound.

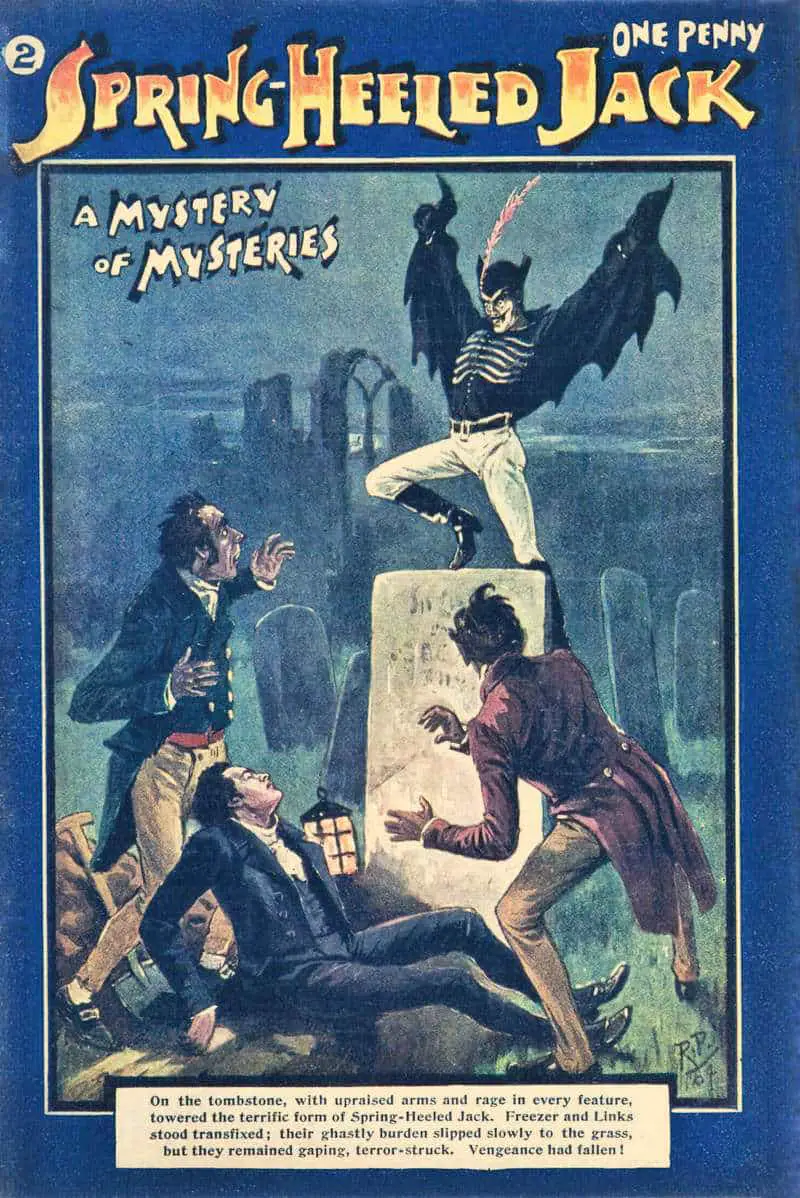

- Within “Strawberry Spring”, Stephen King’s narrator opens with a reference to a figure called “Springheel Jack”. Later on, we learn the name comes from a serial killer. However, the legend of Springheeled Jack is older than that. Looking at the poster below, what can you say about Springheeled Jack?

- According to the story, what is a Strawberry Spring?

- The most widely understood folk name for an unusual weather condition is ‘Indian Summer’, and Stephen King mentions this in his short story. Aside from that one, can you think of any names which describe local weather conditions where you live? Perhaps the term is not well-known to people living outside your area because it describes a microclimate?

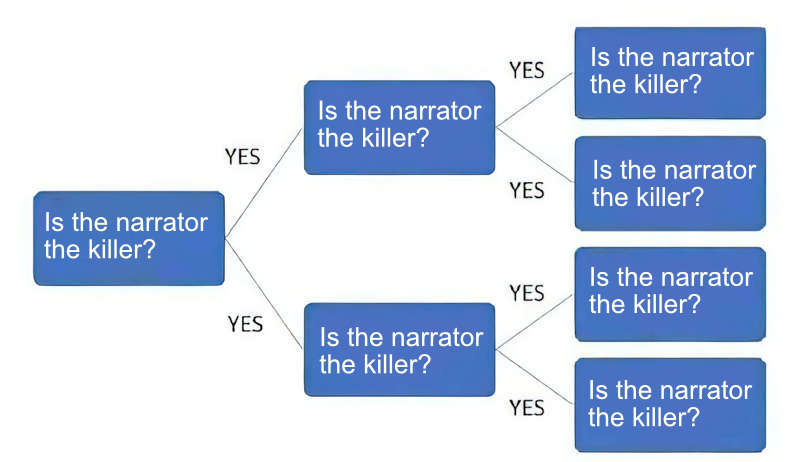

- At what point did you start to think the narrator is the killer?

- At what point do you have this confirmed?

- On re-read, assuming you didn’t pick it up from the first paragraph, how does Stephen King hint on a metaphorical level that the narrator is the killer, even before he starts dropping obvious hints?

- How does Stephen King convey the narrator’s confusion? Talk about symbolism and also story structure if you can.

- King wrote this story in a slightly different voice from his usual work. Though still recognisably Stephen King, how is the voice a bit different, and why?

- “Strawberry Spring” is basically the story of a man who changes in a supernatural way when a specific rare weather condition occurs. What common folklore does this remind you of?

- What does this short story have to say about how we think about violent crime perpetuated against young women?

SETTING OF STRAWBERRY SPRING

PERIOD

The story is told on March 14, 1976, when a husband recalls his time at college. He attended college 8 years earlier, which makes it 1968.

England’s Springheel Jack was supposedly operating in the 1830s, with the most notable report occurring in 1838.

DURATION

One spring, followed by a flash forward to the next Strawberry Spring when the narrator is married.

LOCATION

Maine

ARENA

in and around a college campus

MANMADE SPACES

New Sharon Teachers ‘ College

NATURAL SETTINGS

I imagine the small Maine town is surrounded by beautiful natural features which means the campus sort of straddles civilisation and dangerous nature.

WEATHER

Blackberry Winter is a colloquial expression used in south, midwest North America; as well as in Europe, Sinosphere Vietnam and East Asia, referring to a cold snap that often occurs in late spring when the blackberries are in bloom. Other colloquial names for spring cold snaps include “dogwood winter,” “whippoorwill winter,” “locust winter,” and “redbud winter.”

“Blackberry Winter” is the name of a frequently anthologized short story from 1946 by Robert Penn Warren.

Wikipedia

Stephen King’s Strawberry Spring was a weather phenomenon invented for the story. The term refers to a false spring or unusually warm and foggy spell of weather in a Maine winter. But because King’s work is so popular, the term has entered the lexicon to some degree. You’ll find a definition on Urban Dictionary and at Wikipedia, for example.

Why invent “strawberry”, though? What does the fruit have to do with anything? There doesn’t seem to be symbolic relevance, beyond perhaps, the deliciousness. Strawberries are red, and so we reach out and pluck them to consume, and the killer is doing a similar thing to the young women on campus.

I suggest instead that King was riffing on what several Native American tribes called “Strawberry Moon”:

According to The Old Farmer’s Almanac, which first began publishing names for full moons in the 1930s, the full moon in June was dubbed the Strawberry Moon … to match the short harvest season for strawberries.

ABC

Other examples of rare seasonal phenomena utilised or made-up by authors:

- Ray Bradbury invented “rocket summer” for The Martian Chronicles and “The Long Rain“, a short story from The Illustrated Man collection. In “All Summer in a Day“, rain falls for seven years, with a very brief respite of “sunshine”, which stands as a metaphor for the brevity of childhood, and its associated joy.

- “Blackberry Winter” is a frequently anthologized short story from 1946 by Robert Penn Warren. The term refers to the strange cool period that takes place in a mid-century Tennessee June.

The fog is important, too. Fog in stories frequently symbolises confusion, and so it does here.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

Across “Jack the Ripper” stories, little empathy is extended to the young female victims. I limit exposure to these stories myself, as the harrowing reality of gendered violence perpetuated mainly by men against real women continues to be mostly a non-event, almost expected. True crime can sometimes do a better job of illuminating society’s ills than fiction.

Within the wider world of “Strawberry Spring”, Stephen King’s narrator talks about the Vietnam War, in which many young Western men were conscripted, others volunteered. By referring to this real world event, King creates verisimilitude.

But also, the narrator of this story is pretty much the inverse of the soldier archetype. Although warmongers recruit any young and able man they can source, the narrator of this story seems stuck in an earlier century, almost vampiric. Rather than war and politics, this fellow’s interests lie in old poetry. Basically, the Vietnam war background provides an interesting juxtaposition.

One way of reading this story: You don’t have to attend a war to experience violent crime, especially if you’re a woman. You just go about your daily business in the so-called peacetime of America, and violence can still find you, anywhere, anytime.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “STRAWBERRY SPRING”

As you read, you may notice the narrator circling back, repeating himself. “Strawberry Spring” is an excellent example of a circular, vortex shaped plot. In circular stories, seasonality tends to be important. Interestingly, circular stories featuring seasons tend to feature as heroes either women and girls or less manly men, and that’s the case here, with our effete teacher’s college student who specialises in Romantic poetry.

Vortex plots are frequently fast paced and full of action because there’s some kind of race going down. But there’s also a slow, reflective version of this plot shape, in which a character is revisiting memories trying to work something out.

In the telling of the story, the narrator seems to arrive at a self-revelation. By telling the story, mostly to himself, he’s worked the mystery out.

In this way, the story structure works hand-in-hand with the fog symbolism.

SHORTCOMING

The narrator is eventually revealed to be a 1960s/70s version of Springheeled Jack, who may or may not have been based on a real man. It seems more likely to me that the figure is an amalgamation of many scary men who refused to respect women’s bodily autonomy as they tried to go about their business in the Victorian era.

This guy insists he has no recollection of his murders. He loses his sane, thinking self, himself a victim of a weather event which takes possession of his body.

All well and good, if we consider fiction ‘just a story’. However, the idea that men lose control of their actions and cannot be held responsible for violence they inflict is written into law.

Perhaps the best (read: worst) example of this is the gay/trans panic defence. Here in Australia, the defence was abolished shockingly recently, in 2020. There remains much work to be done on ensuring laws address all crimes motivated by hate or prejudice.

DESIRE

The first person intradiegetic narrator simply wants to understand what’s going on with his memory lapses. That’s why he’s writing this story.

We might consider this a story-within-a-story, though. In the hypodiegetic story (which takes place on campus eight years earlier), the narrator wants to know which despicable man was murdering the women.

OPPONENT

Generally in narrative, when the main character’s ‘biggest opponent is himself’, the story falls a bit flat. Another opponent is required.

The exception is in these Jekyll and Hyde category of stories, in which the main character is quite literally two separate personalities.

PLAN

Our narrator is a Romantic flaneur type of guy, wandering around campus observing the happenings. We don’t see him interact with anyone. For the hypodiegetic layer of story, he is very much a viewpoint character rather than a ‘main character’. That only starts to flip when Stephen King drops strong hints that he is the murderer.

The first main hint for me was the bit about the fangs. He had the good sense to take his fangs out for the photo. When reading that, it could be a red herring. Like, maybe he was at a Hallowe’en party? Or, being a student of Romantic poetry, maybe he dressed like a Vampire Goth? The point is, this is Stephen King asking us to wonder.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Psychological horror keeps violence short, or mainly off the page. This narrator is unable to give us the gory parts anyway, since he loses his memory. Stephen King makes use of the Rule of Three, in which Springheel Jack murders three women on campus. Three is enough to establish a pattern. This is a thing that he does and he won’t stop doing it, for as long as there are Strawberry Springs. (I wonder how climate change has affected the guy.)

ANAGNORISIS

We probably realise before he does, but this guy is Springheel Jack.

By the time he tells us he’s lost his memory, it is very clear what’s going on. If you re-read the story, now it’s clear from the beginning. Stephen King’s atmospheric ‘fog’ has cleared for us.

THE SYMBOLISM OF DUPLICITY

Namely, King achieves this by establishing the idea that no one can really know anyone else for sure. He illuminates this idea by zooming in on how people talk about the young woman victims. As well as offering commentary on the salacious aspect of violence inflicted against women, by showing us the many conflicting stories which are concocted by people who purported to know the victims better than they really did, King puts in our heads that this duplicity can apply to literally anyone. No one is exactly how they are perceived to be.

More than that, when we repurpose a harrowing true crime story as titillating horror, we are distancing ourselves from the crime. We may profess outrage and horror: How could anyone do such a thing? But by withdrawing empathy from the real life victims, focusing instead on the mysterious perpetrator, aren’t we committing a “two-faced” act?

NEW SITUATION

In fact, he’s still not come to terms with it. He’s in denial, knowing only that he ‘doesn’t remember’. But readers are left sure of the truth.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Since the narrator remains slightly in denial, we can see this story will repeat, and is repeating as we read. He doesn’t have the capacity to stop himself.