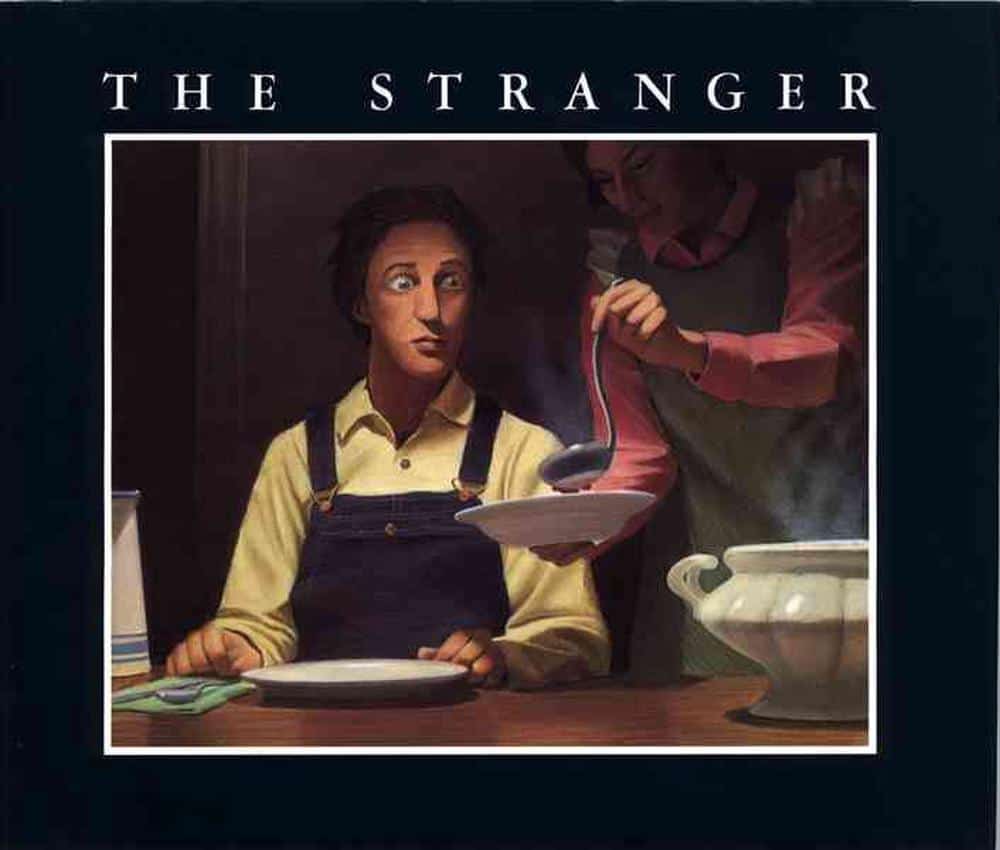

The Stranger (1986) is the seventh picture book written and illustrated by popular American storyteller Chris Van Allsburg.

This picture book provokes as many questions as it answers, and reminds me of the Australian picture book written and illustrated by Shaun Tan in which a tiny ‘exchange student’ arrives in an Australian home, he admires his new surroundings, and then he departs. The Stranger utilises a similar plot, though it asks us to consider different things. Eric asks us to question what we consider normal about our own culture. The Stranger encourages us to take a closer look at our surroundings, and in aid of that, teaches audiences to close-read a text. This picture book is therefore popular with teachers working on inference skills.

The inciting incident happens on the first page when a young girl’s father runs over a man on the road. At first the father thinks he’s hit a deer, then he is worried he’s killed a human. The pictures reveal that the stranger and the father look almost identical; the man has come face to face with his own mortality, and that’s just for starters.

Running someone over on the highway, meeting yourself face to face… this feels like the fodder of American urban legend; many of those are set on highways. The story gets even more urban-legendy when the doctor’s broken thermometer suggests the man may be a ghost.

PRE-TEACHING THE STRANGER

QUESTIONS

- When you were little did you used to think objects (or toys) were alive?

- In stories, what is it called when an object comes to life?

- List stories about strangers who come into the house. Did the strangers of these stories turn out to be good, bad or somewhere inbetween?

Both personification and anthropomorphization assert intangible human characteristics. anthropomorphization imposes physical or tangible human characteristics onto the subject to suggest an embodiment of the human form.

(See here for more on anthropomorphism and personification.)

SUPPORTING TEXTS

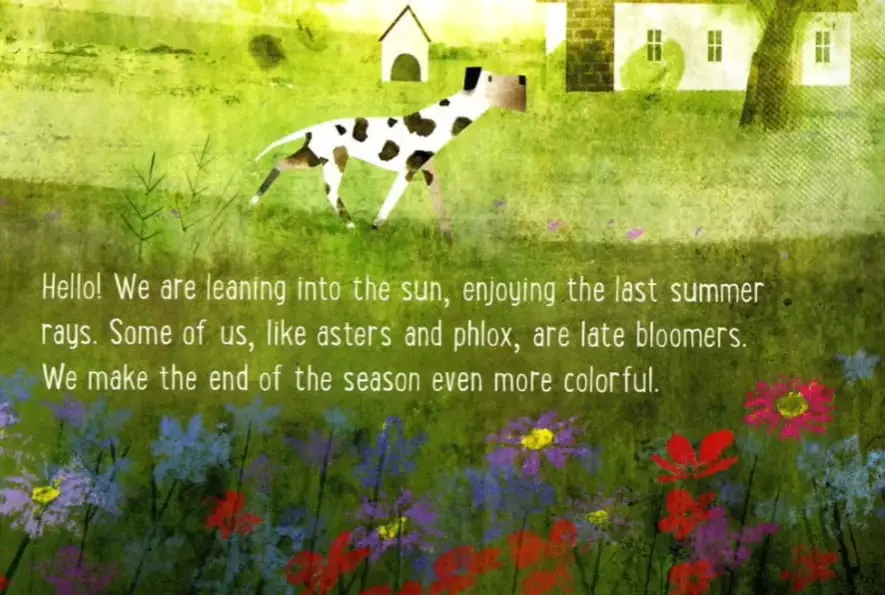

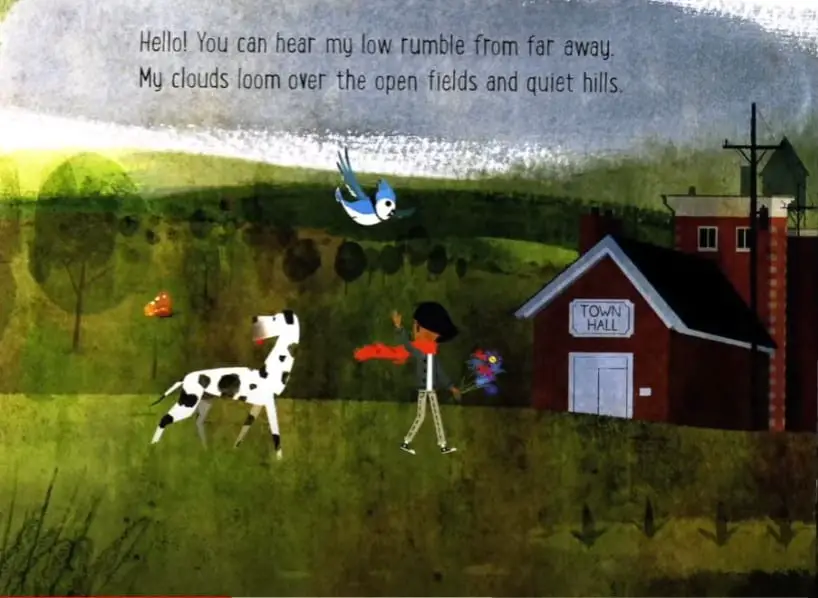

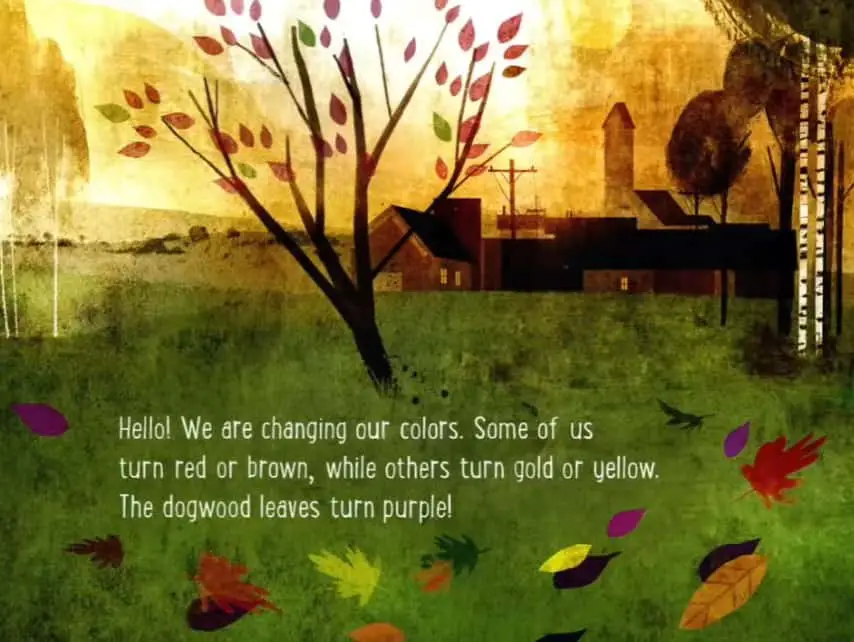

If teaching the concept of personification, examples can be found all over children’s literature but a very pretty modern example is the picture book for preschoolers, Goodbye Summer, Hello Autumn by Kenard Pak. If you enjoy Jon Klassen’s textures, you’ll lovePak’s textures, too, and his autumnal colour palette. The text is very similar to Goodnight Moon. A girl walks through the book as seasons change from summer to autumn, and nature talks back to her. Each page offers an example of personfication (reflecting the mindset of animism: the attribution of a living soul to plants, inanimate objects, and natural phenomena).

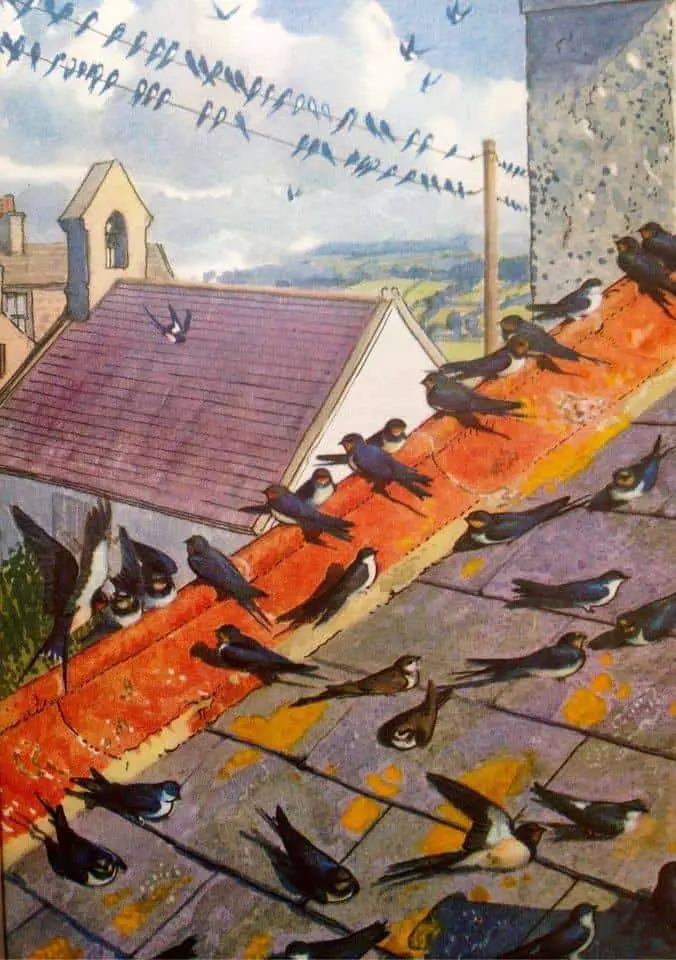

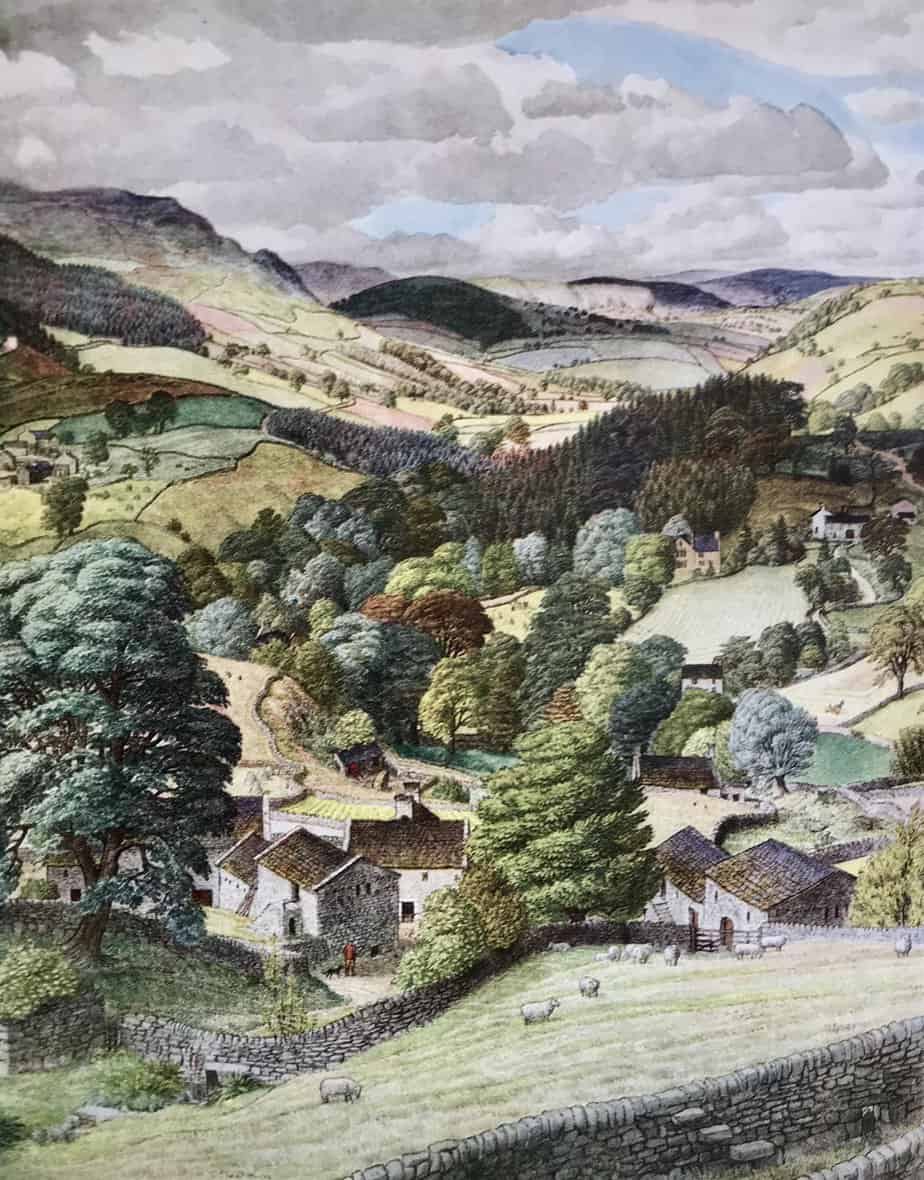

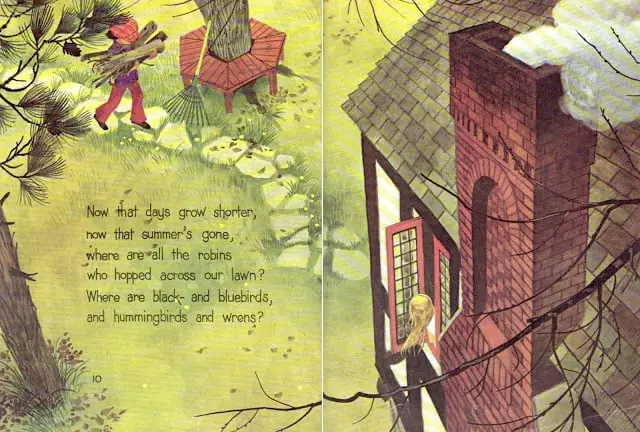

There’s a long tradition of picture books which teach young readers to pay attention to nature, and to the changing of seasons. One example is What To Look For In Autumn (1960). In the illustration below, we are encouraged to view the world from a bird’s point of view.

Many students may have seen Rise of the Guardians (2012), in which Jack Frost is the main character.

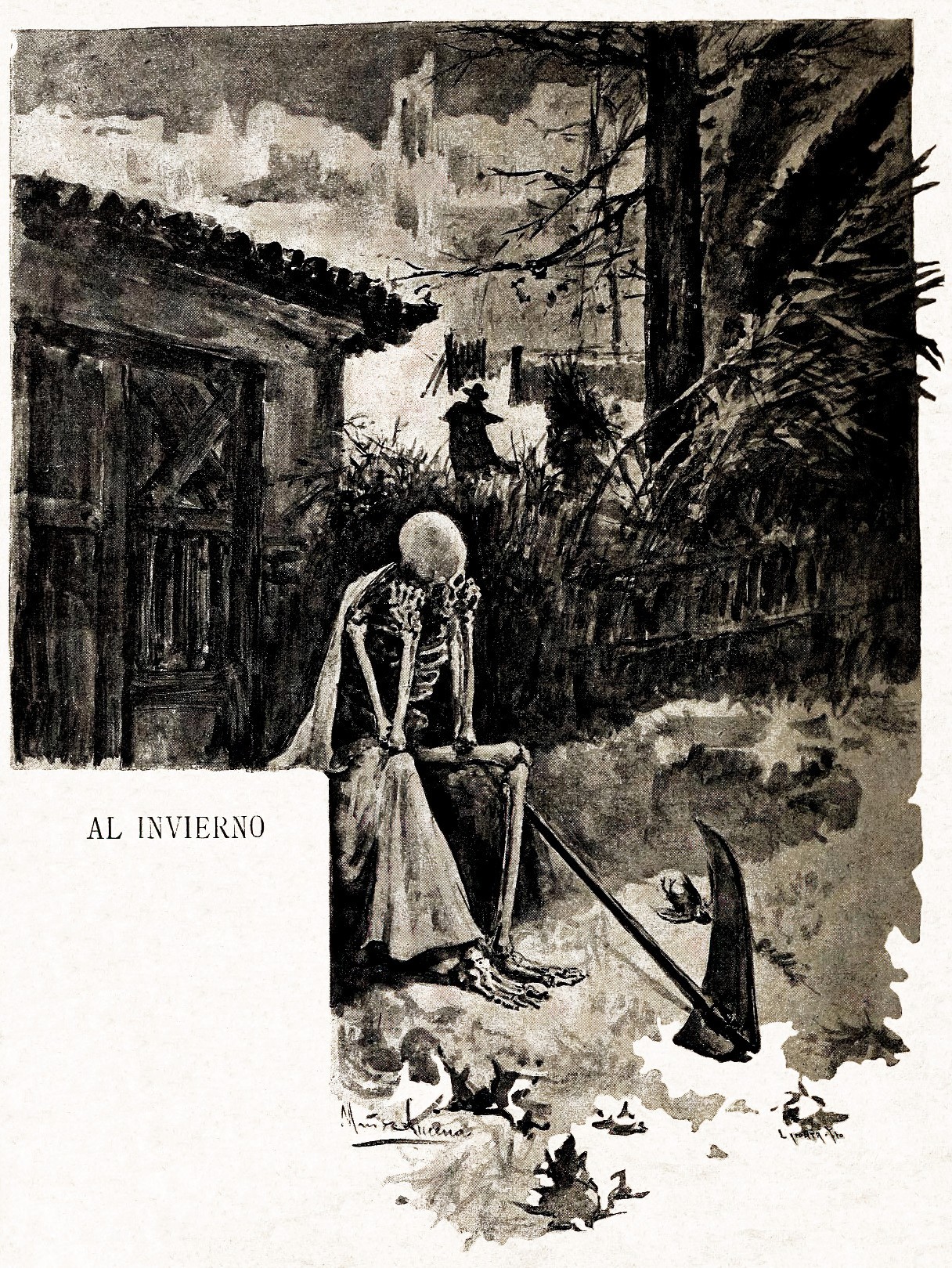

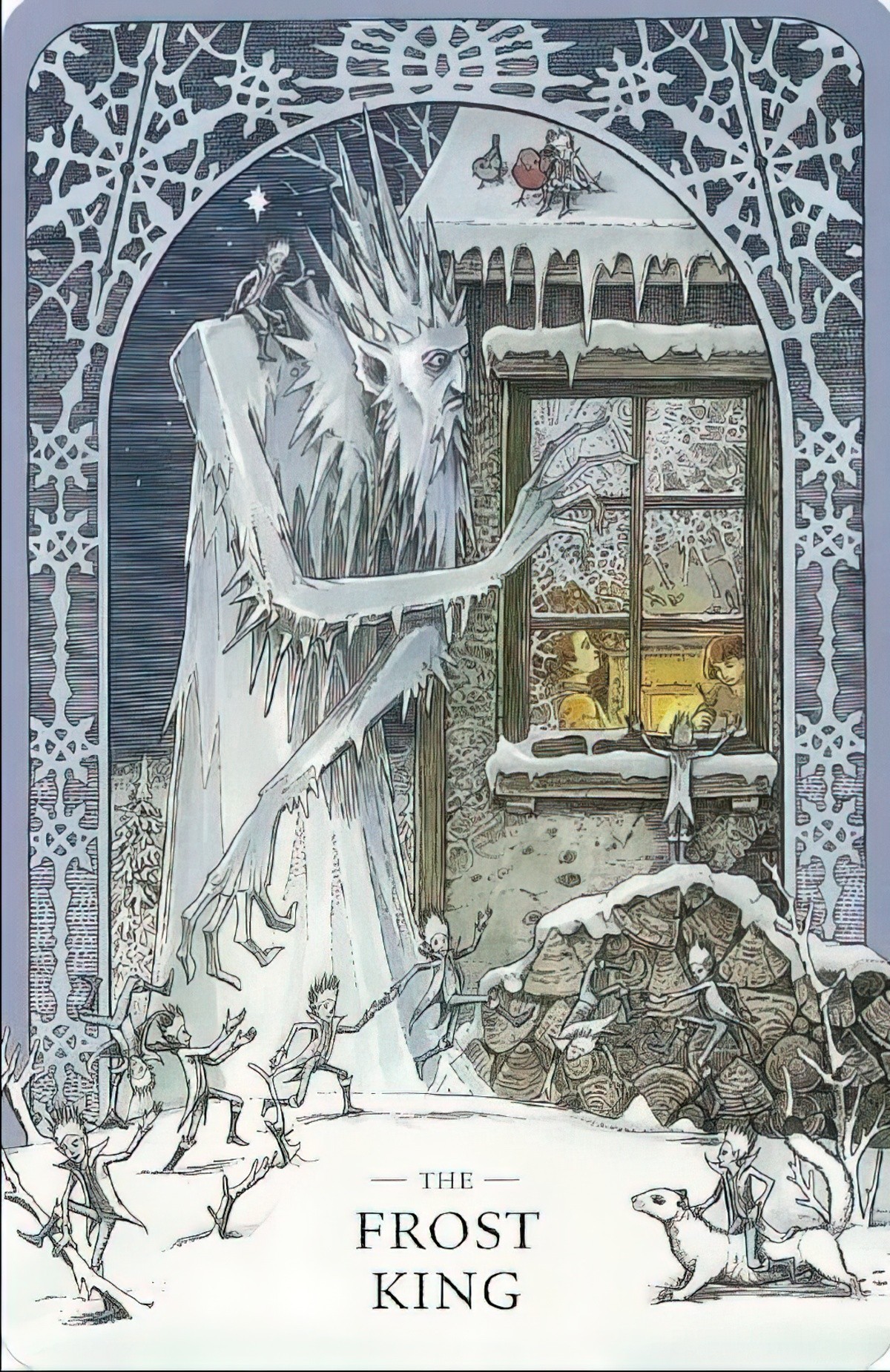

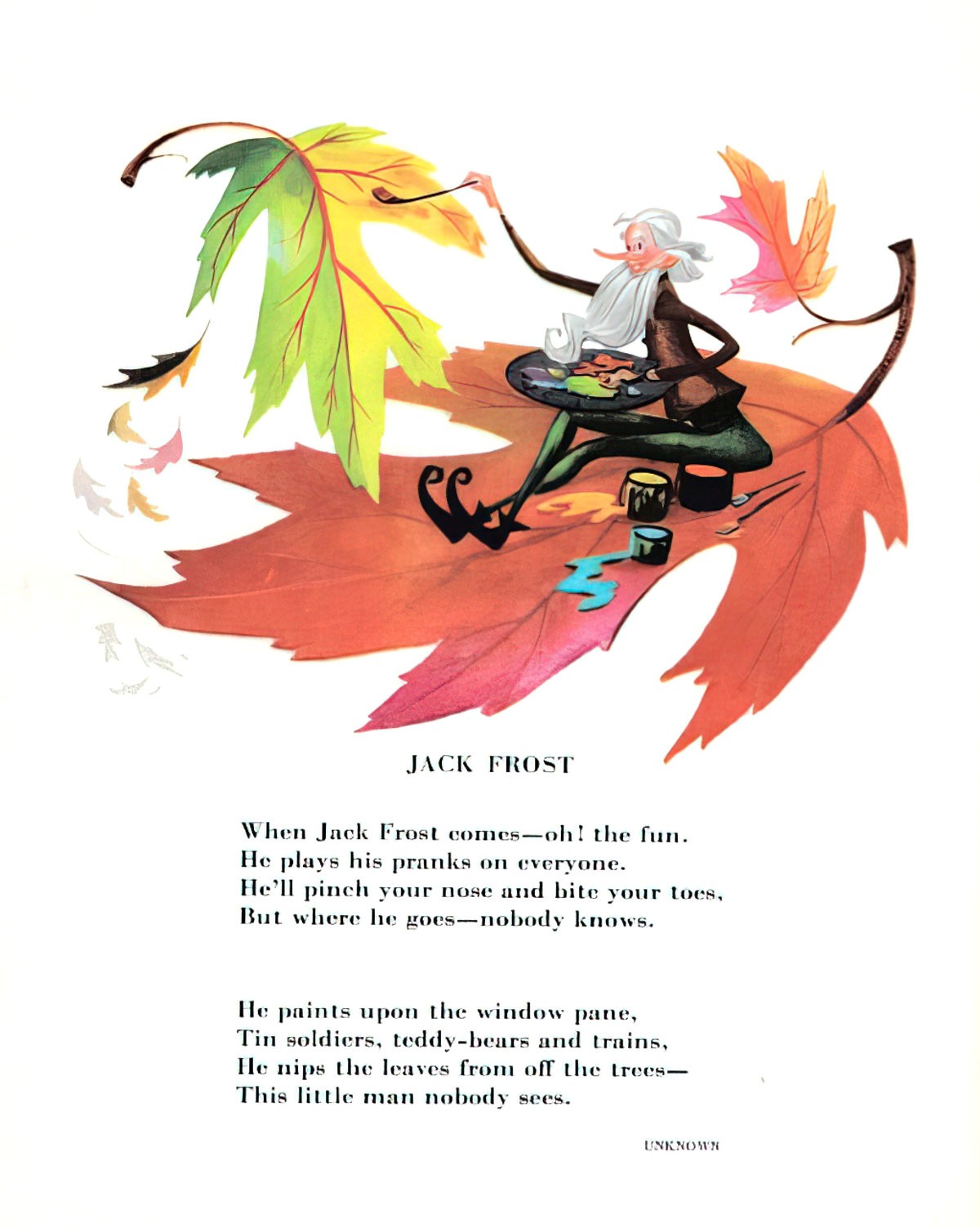

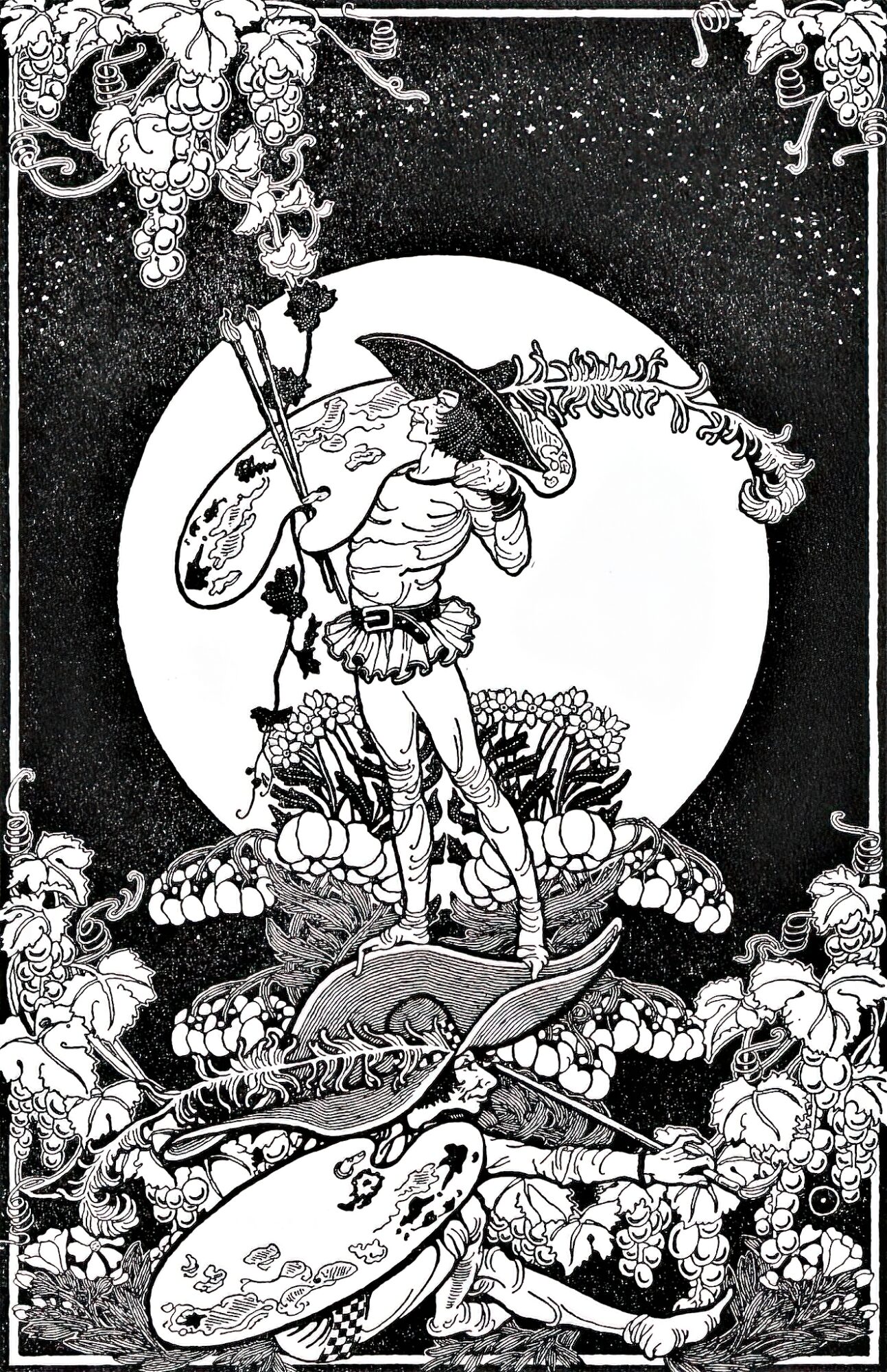

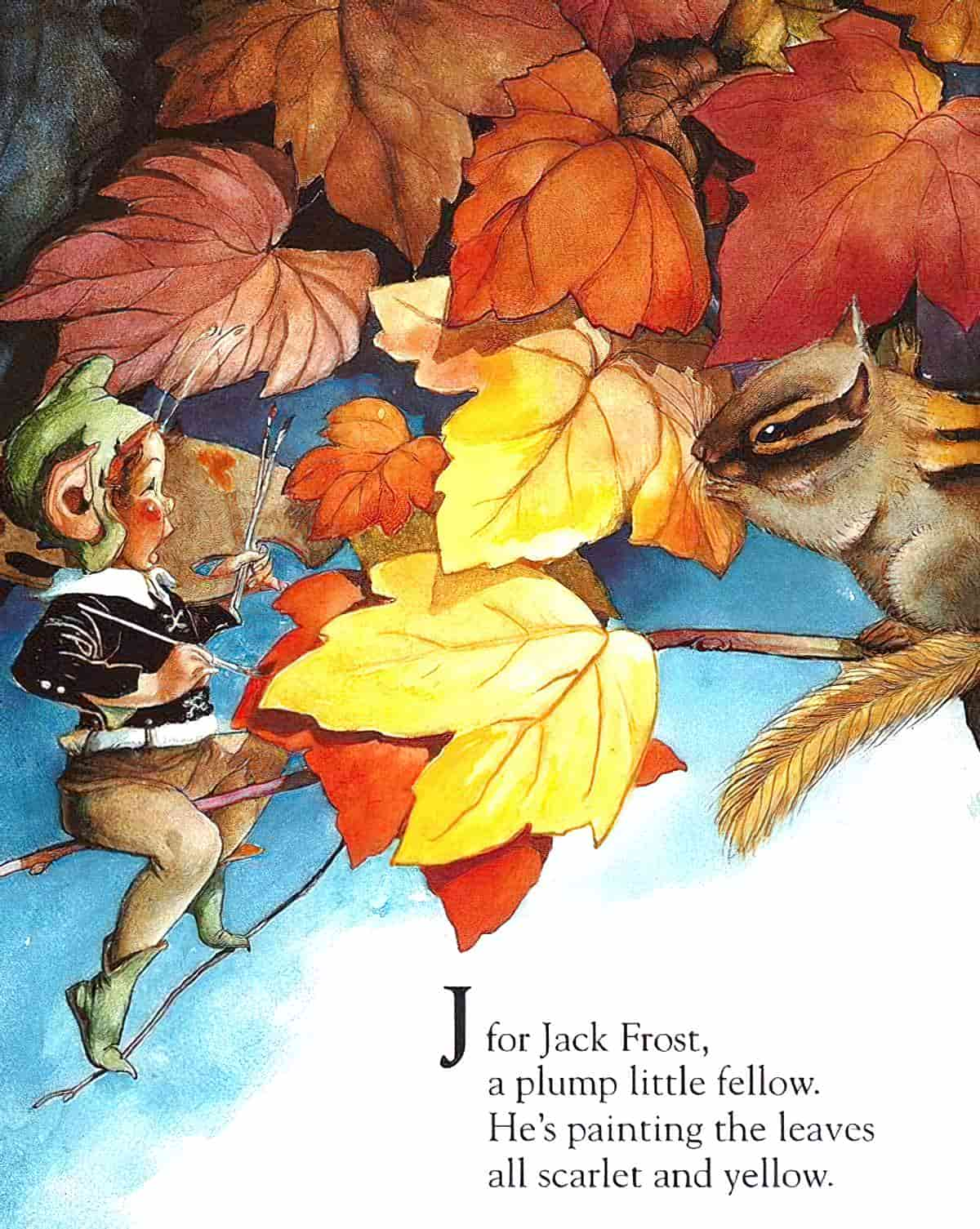

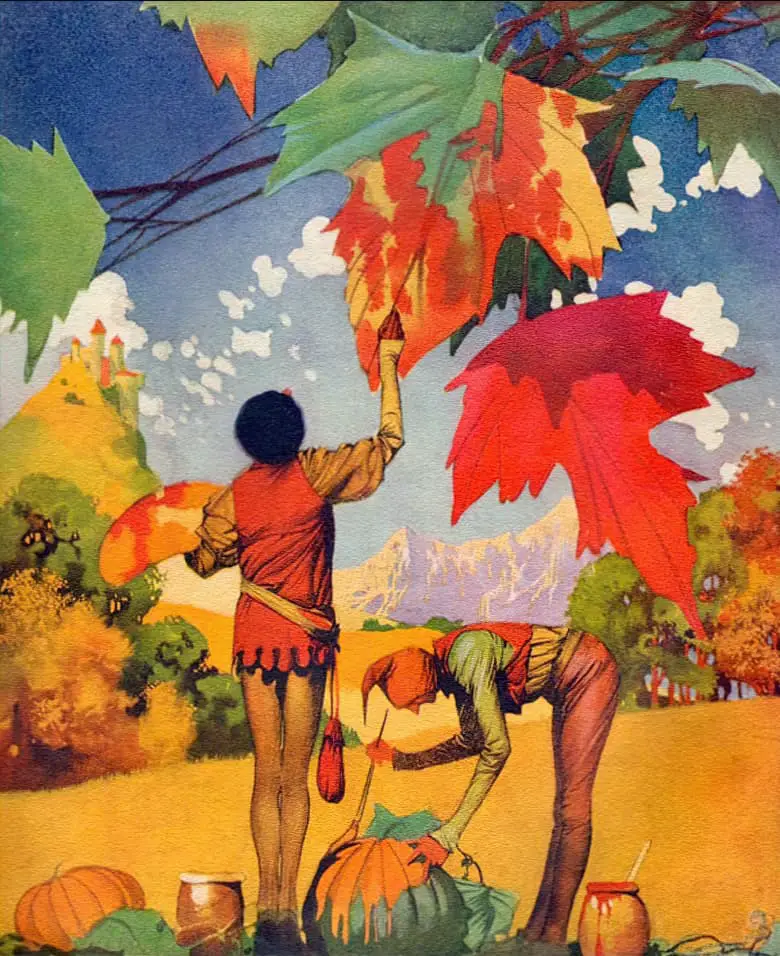

“The Stranger” is basically one long personification of winter. Here are some others, by various artists:

Another compare and contrast text comes from Chris Van Allsburg himself: The Widow’s Broom is another story about a supernatural stranger who comes into the house. That story also features animism and also uses deliberate conflation of two characters into one.

British author illustrator Anthony Browne reminds me of Chris Van Allsburg in many ways. In Browne’s retelling of Hansel and Gretel, the step-mother and the witch are the same person. The reason in that text is clear: to emphasise the scariness of the mother-figure, and also to suggest that the trip into the forest happens in the children’s subconscious. (Forests are the symbolic subconscious.) Likewise, In The Stranger, the farmer/father and the stranger might be considered the same person. The interesting question is: why?

Perhaps older students will be familiar with the Pan character from the (unabridged) Wind in the Willows or The Secret Garden.

Older students also tend to love urban legends. I might consider opening with a few of the highway stories. Some of these can even be found in children’s books and are very quick to read e.g. the popular American Halloween book In A Dark, Dark Room And Other Scary Stories contains “The Night It Rained”.

There are also plenty of examples online of urban legends which begin on highways, and which leave the driver wondering if he just had an encounter with a supernatural character. (When the main character of these stories is a woman, the plot tends to be different — the predator will be very human, and wanting to kill her.) There are many things to talk about here, including whether a story encourages readers to be kind to strangers, or even more wary of them. This picture book teaches people to be kind to strangers, so a compare and contrast with an urban legend which does the opposite would be useful. “Stranded On The Side Of The Road” is a good counterexample.

SETTING OF THE STRANGER

The illustrations are rendered in coloured pencil, with a variety of sketching techniques. The trees look pointillist, and the sky contains long, continuous lines.

Text and pictures have dazzled readers as Mr. Van Allsburg has moved from rich and muscular black-and-white drawings to a cool palette that sometimes suggests the Pointillist masterpieces of Georges Seurat.

Anne Rice, The New York Times

PERIOD — as atemporal as possible, though the existence of technology such as a truck will necessarily place the story in time. More interesting than working out the exact ‘date’ of the setting: Why is this story atemporal, and how does Van Allsburg achieve that?

Stories which focus on the coming and going of seasons are about the inevitable circularity of life. We see this idea in many stories, including the Bible (Ecclesiastes 3:1-8), popularised in 1965 by a band called The Byrds.

REAL OR IMAGINED — To what extent does this story play out in the veridical world, versus inside the girl’s imagination?

Notice how the stranger looks very much like the little girl’s father. They wear similar clothes. This can be explained in a surface-level reading of the text because the stranger has borrowed the father’s clothes, but even their face and hair is the same. The stranger is a more jovial version of manhood than the father, dancing and singing and taking time to sit with the girl on the grass looking at the sky. In this respect he’s more of an archetypal grandfather character (a la Old Man Frost.) Perhaps this is a little girl imagining what her father could be like (but isn’t). Or perhaps this farmer father has had a very good year crops wise, due to the weather (part of the story), and the little girl has constructed her own story about the newly exuberant father who suddenly seems to be in a wonderful mood.

Whether real or imagined, it soon becomes apparent to the reader that there are supernatural elements in this story: The doctor’s thermometer is ‘broken’ (not registering life heat at all); the visitor has a way with rabbits, and is highly interested in the flock of birds flying across the sky. Surreal detail in the illustrations teaches readers to ‘read’ the pictures.

LOCATION — Although this story appears otherworldly, it is also unmistakably American (from a non-American point of view).

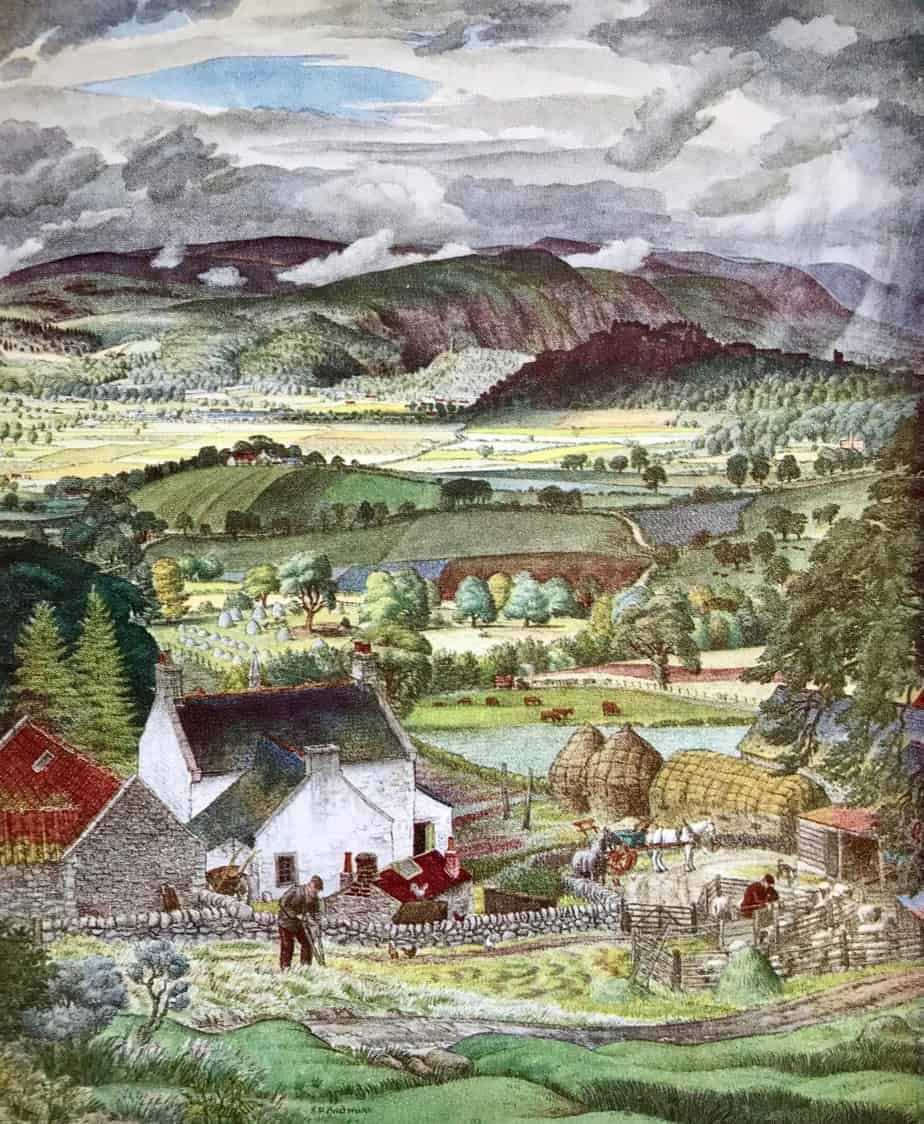

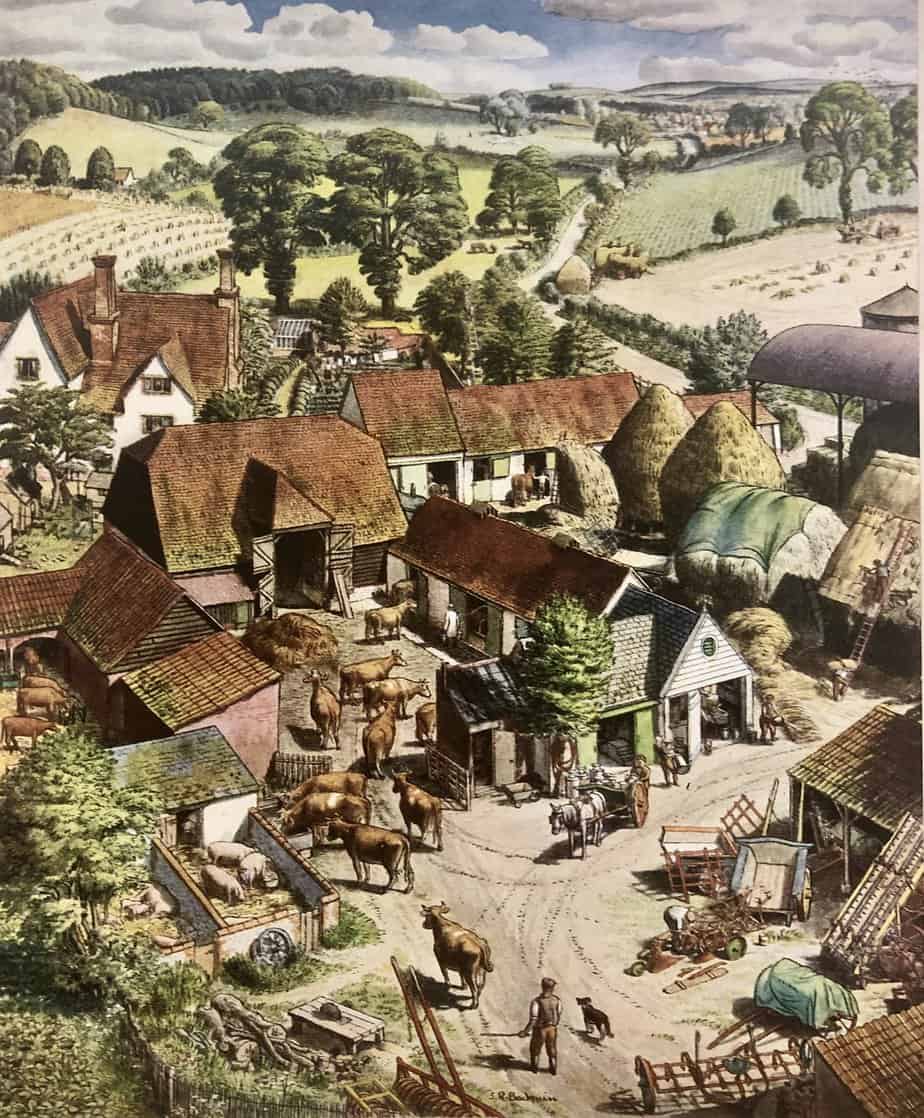

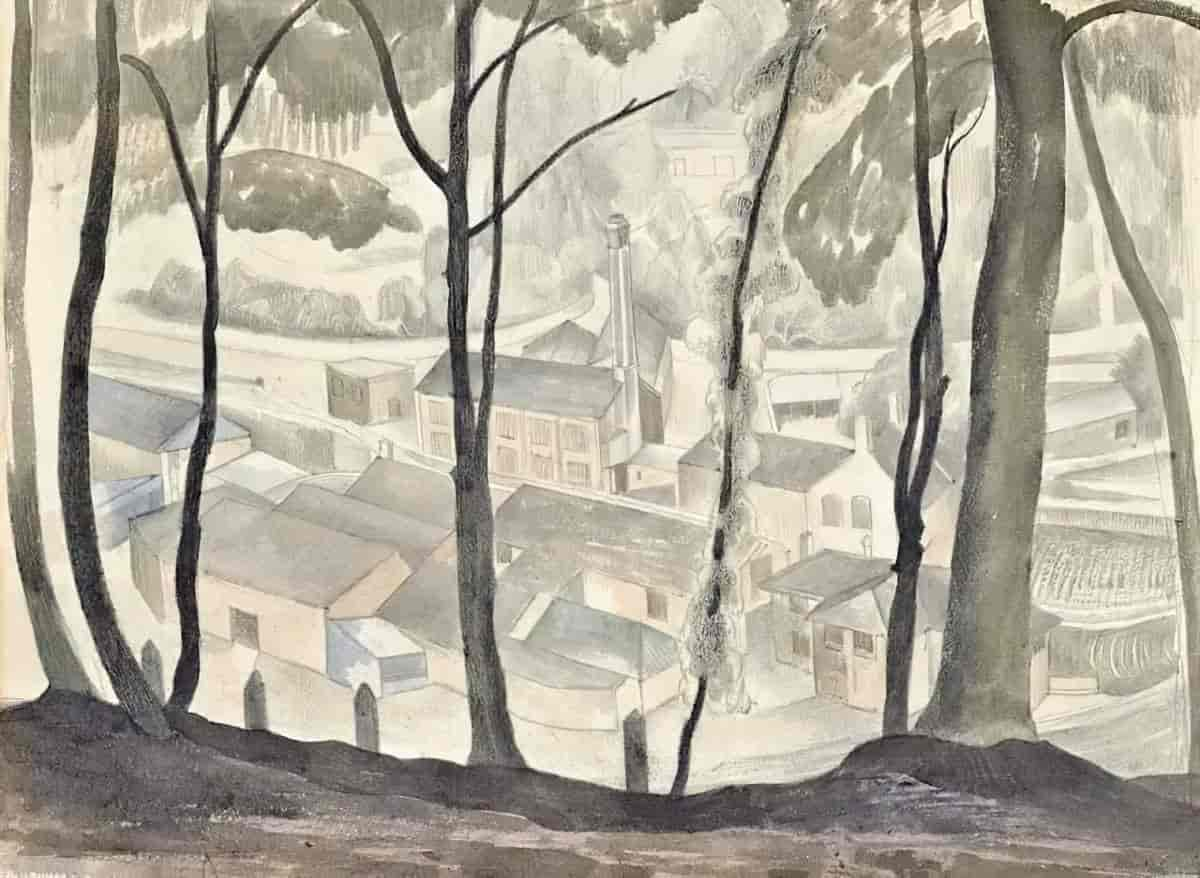

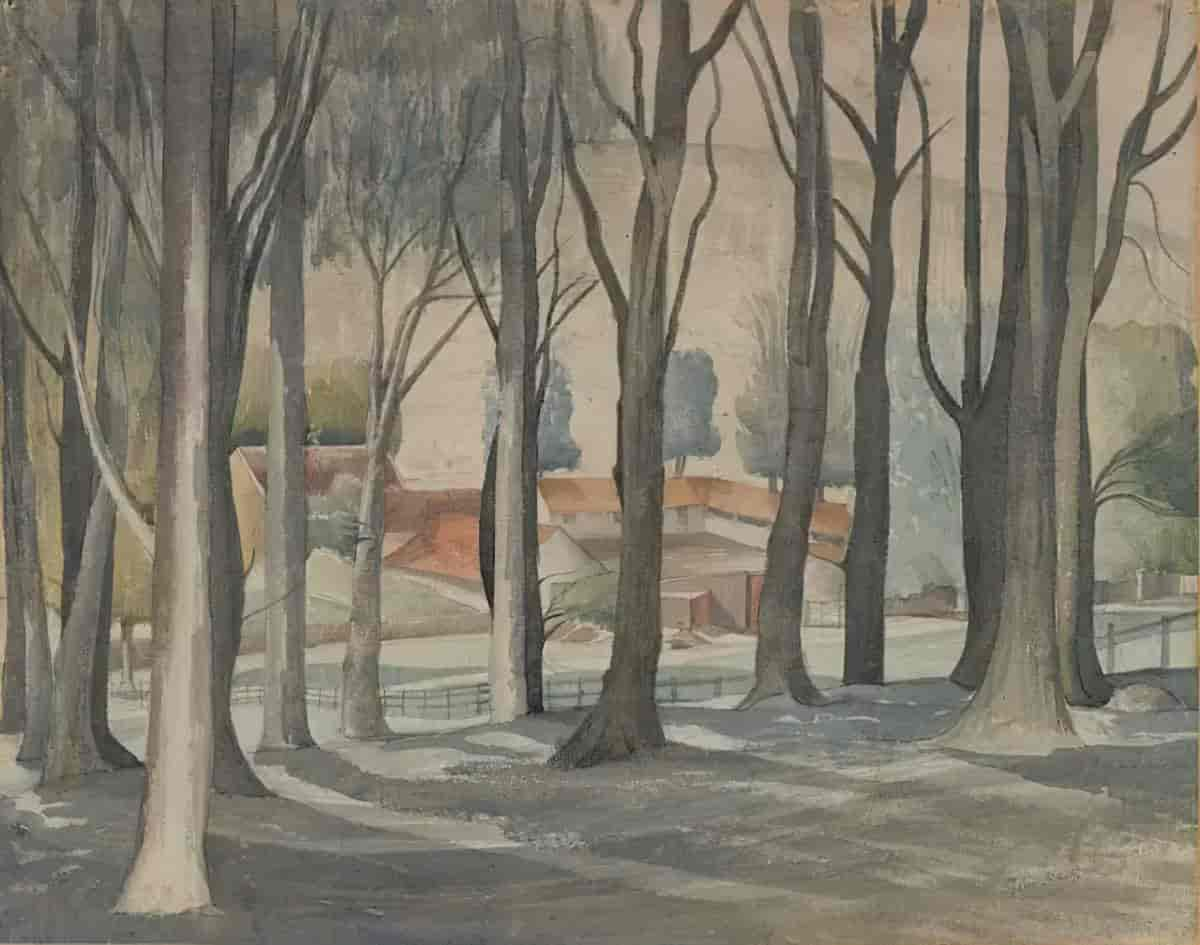

For contrast, here are two scenes from ‘British Countryside in Colour’ by illustrator S.R. Badman

ARENA — The farm is at the centre of the story, and the reader is afforded a glimpse of the vista surrounding this farm. The colours of trees in the distance are important to the plot. There’s no suggestion of neighbours who might otherwise come to the rescue if the stranger admitted to your home happened to be a psycho killer.

MANMADE SPACES — The family lives in a symbolic dream house and on a cosy storybook farm probably inspired by the author/illustrator’s own experience growing up on an American farm. The farm is your cosy mid 20th century farm in which farmers can pretty reliably expect to keep producing without the interference of terrible natural disasters which will put them out of business. For farmers, the coming and going of the seasons must be a hugely reassuring thing, especially in down years.

NATURAL SETTINGS — farmland with roads running through it

WEATHER — This is a gentle and beautiful autumn

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — The truck, for the plot.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE

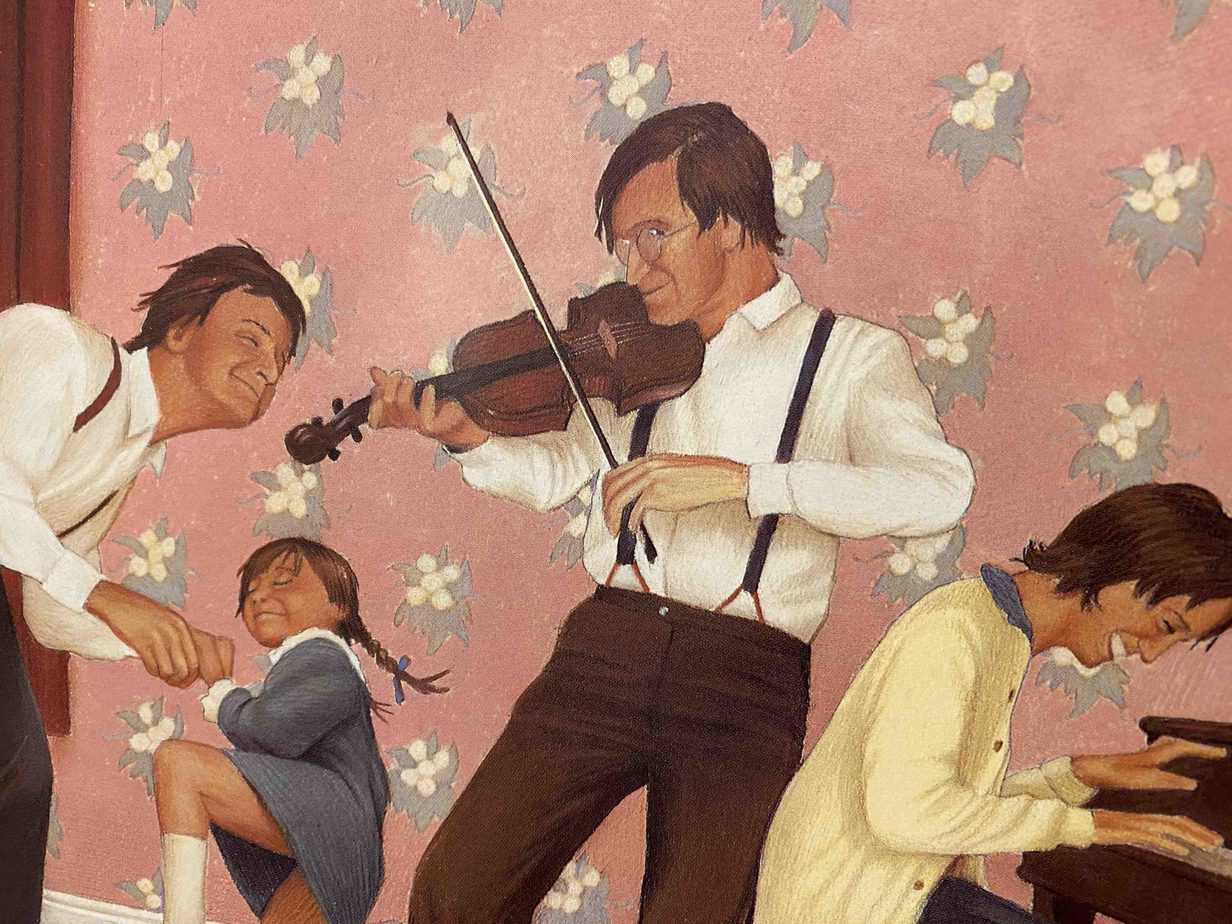

[E]veryday human life is presented as wondrous. It seduces and satisfies the super-natural visitor. And the visitor’s magic, rather than being sinister or unnatural, is part of nature itself. […] For the first time, we are brought close to Mr. Van Allsburg’s characters and their feelings. The innocent facial expressions of the stranger, the blissful smile of the farmer’s little daughter as she looks up at the stranger, the ecstatic dance of the two while the farmer and his wife make music – these are almost without precedent in the artist’s other books, which are more cerebral and more remote.

Anne Rice, The New York Times

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE STRANGER

PARATEXT

The enigmatic origins of the stranger that Farmer Bailey hits with his truck and brings home to recuperate seem to have a mysterious relation to the weather. Could he be Jack Frost?

MARKETING COPY

Okay, this is unusual. Marketing copy gives readers a massive hint on how to read the text. Jack Frost, hmm. Perhaps it was Anne Rice, of all people, who first put this idea in readers’ heads with her review of The Stranger in the New York Times when it came out. (An interesting choice for reviewer — I can’t think of another example of a supernatural erotic novelist reviewing a children’s picture book.)

[A] mysterious figure, accidentally struck down by a farmer’s truck, stays with the farmer’s family until he recovers his memory, participating in the life of the farm. The man – it seems – is Jack Frost, or the spirit of winter; the weather cannot continue its change without him, and when he recalls his function, he takes his leave of his human friends with tears in his eyes.

Anne Rice, The New York Times

Later, in a 2004 interview with Scholastic, Chris Van Allsburg was asked the identity of the stranger. He said, “Jack Frost.”

WHO IS THE MYTHICAL JACK FROST?

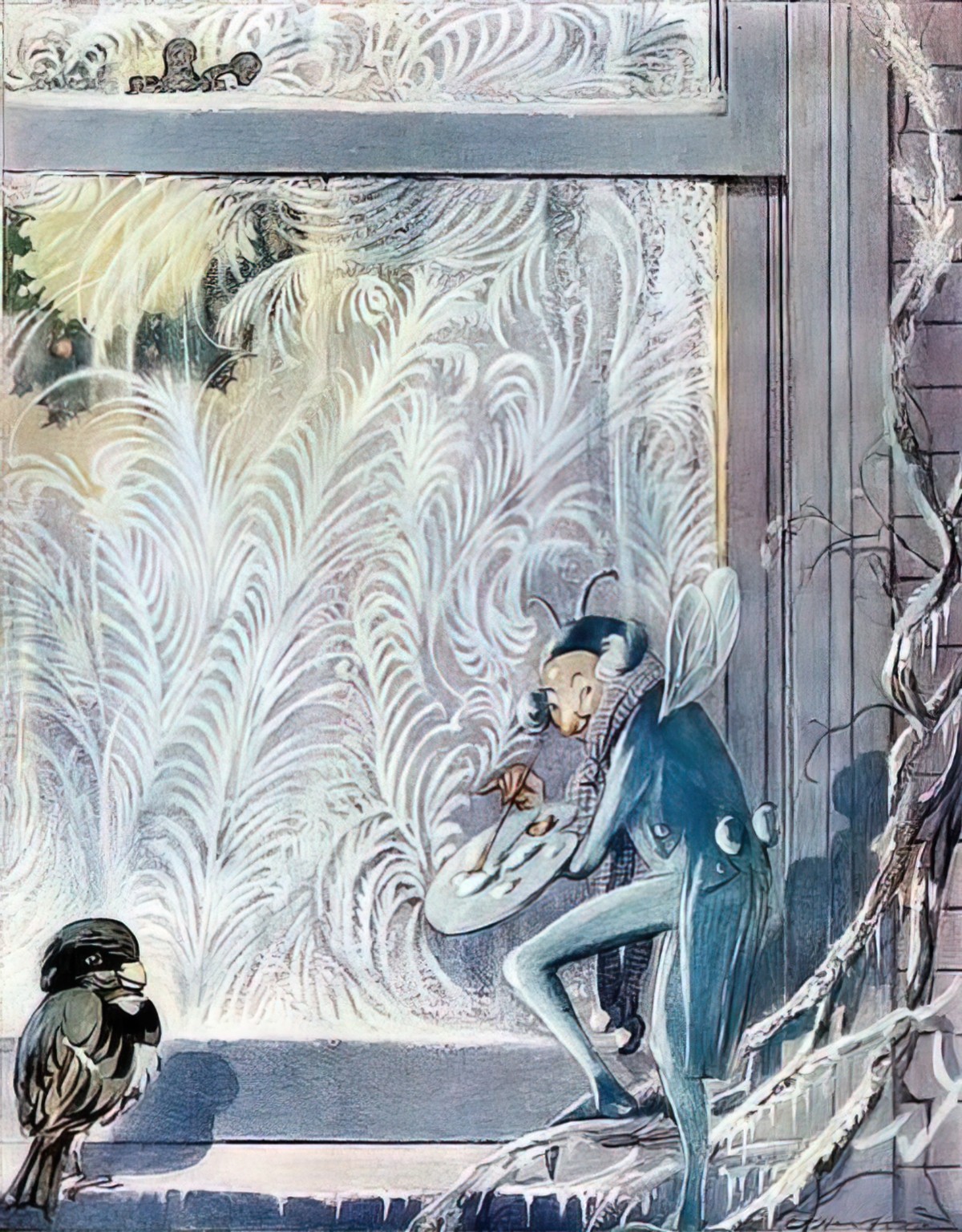

Jack Frost is a personification of frost, ice, snow, sleet, winter, and freezing cold. He is a variant of Old Man Winter who is held responsible for frosty weather, nipping the fingers and toes in such weather, coloring the foliage in autumn, and leaving fern-like patterns on cold windows in winter.

Wikipedia

Old Man Winter is a personification of winter. The name is a colloquialism for the winter season derived from ancient Greek mythology and Old World pagan beliefs evolving into modern characters in both literature and popular culture.

Wikipedia

Note that Jack Frost is not only masculine, but somewhat omniscent and patriarchal. This makes him an ideal mythical figure to map onto a child’s own father. Jack Frost is often thought to be active in the changing of the seasons; he is the demigod who ends autumn and ushers in the winter.

The personification of natural phenenomena is older than story itself. We can go back at least as far as Pan, the Greek demigod. Pan is probably based on a Proto-Indo-European god, and who knows how far back this concept goes; do animals personify their environments? Who knows. (I’m pretty sure my dog thinks hot food is ‘alive’ and needs to be thrashed before eating.)

Jack Frost is much newer than Pan, and more specific to a personification of ‘coldness’, and the changing of seasons from autumn to winter. (Though in this particular story, he seems to bring on autumn, which suggests to me this is not Jack Frost specifically, but a similar, unspecified demigod of nature.)

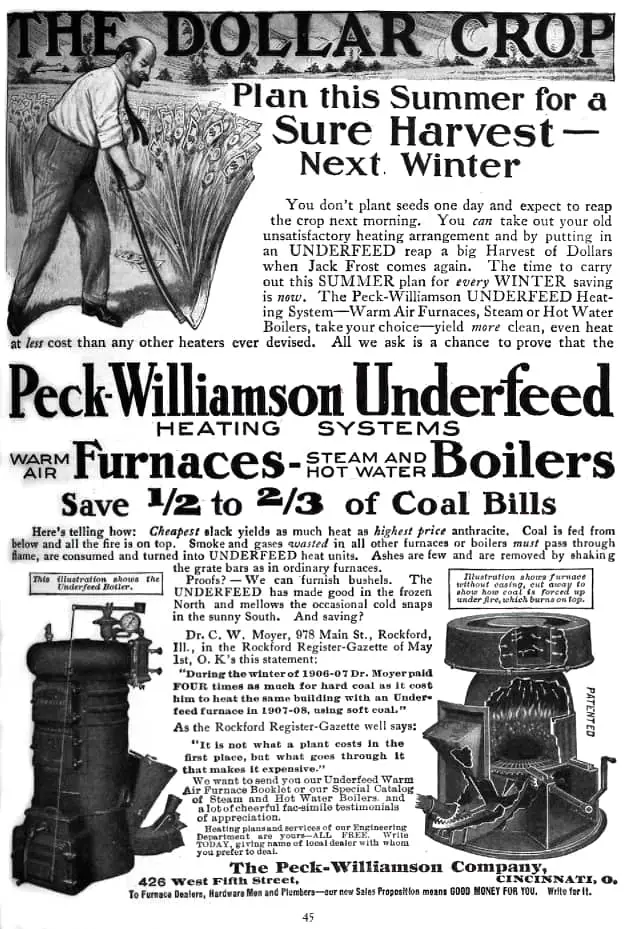

The character of Jack Frost first appeared in written sources around 1734. He became a recurring character in children’s literature from the First Golden Age. In 1875 he starred in the poem “Little Jack Frost”. In 1902 he appeared in The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus by L. Frank Baum. Here he is mentioned in a 1909 advertisement for boilers:

In 1916 he was re-imagined by Arthur Rackham, who illustrated The Allies’ Fairy Book. The contents page of this book tells us the story of Frost is from Russia. (In Russian he goes by a few different names, e.g. ‘Morozko’ and ‘Ded Moroz’.)

The character of Jack Frost continues to appear across children’s media, often in computer games.

For the purposes of this story, the stranger at first seems like a ghost because ghosts are thought to be cold, and the doctor clearly thinks his thermometer is broken. So the stranger could be both ghostly and Jack Frost.

EXAMPLES OF JACK FROST IN ILLUSTRATION

Beside the front door in the hall

all lined up in a row

the Radiator Soldiers stand to fight the cold and snow;

Then Jack Frost comes blustering in to put them all to rout

and their guns go pop-pop-popping

till they bravely drive him out.

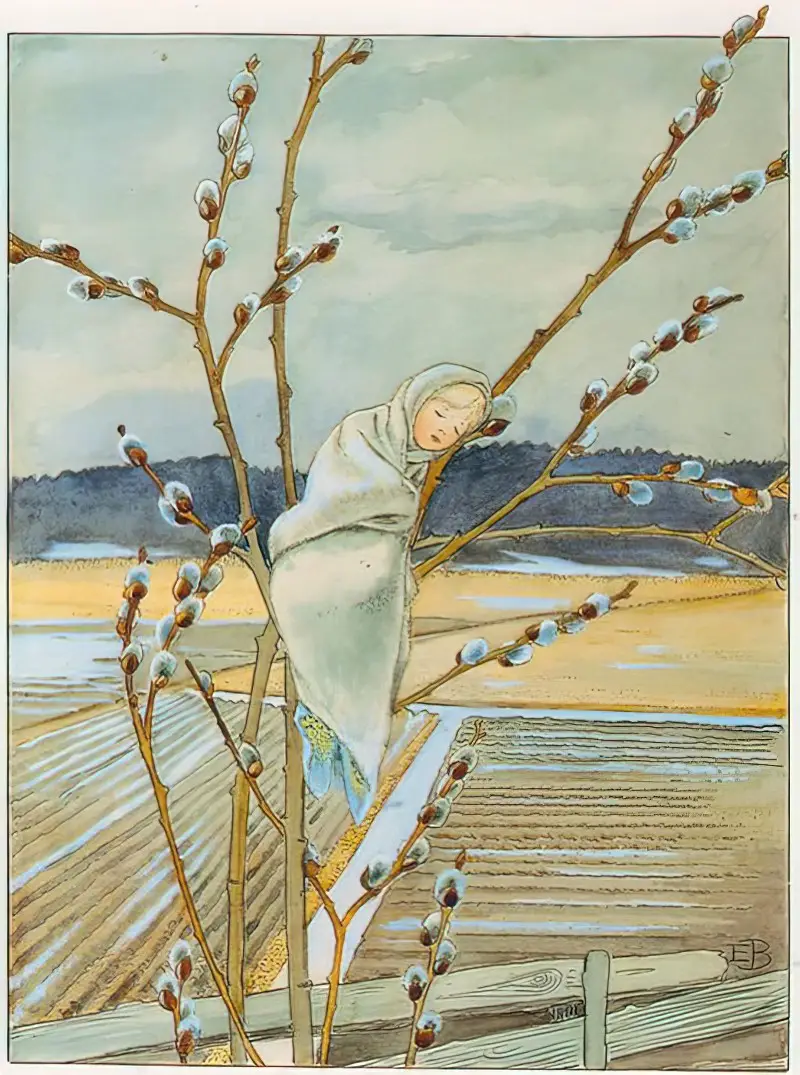

Fairies are also thought to be instrumental in changing the seasons.

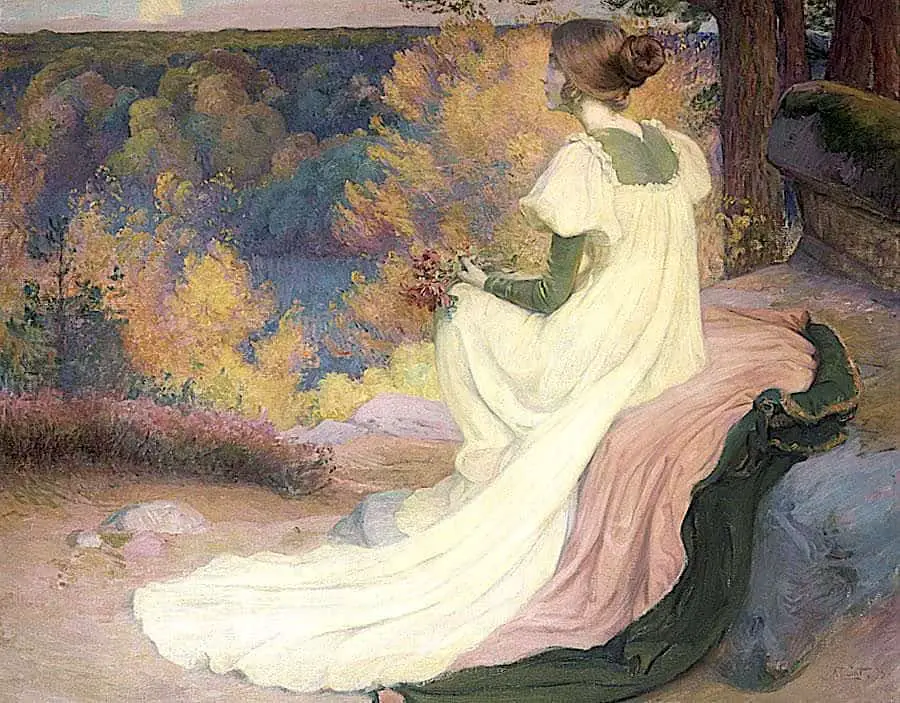

The painting below by French Symbolist artist Armand Point doesn’t look at first glance like it features a fairy, but the ‘woman’ has shucked off a green coat (and wears a green top under her dress). Green is traditionally the colour associated with fairies. She looks out over an autumn landscape and, like the ‘stranger’ in Chris Van Allsburg’s picturebook, she holds a piece of that nature in her hand. Importantly, she sits above all of this, in omniscient ‘god’ position. She also seems to be taking pride in her work.

Of course, it’s also possible to interpret this painting literally: Maybe she’s a girl who the artist dresses in green because she is part of the landscape. She is part of the landscape because she enjoys it very much. (Also, the colours work.) This artist tended to dress his young women in green (or not dressed at all).

VIEW THROUGH TREES

The story opens with a landscape bordered by trees. The dark trees convey an ominous tone, as if something is emerging from the woods. This works even though it is us, the viewer, coming out of the woods.

Here are a few other examples.

SHORTCOMING

Unusually for a picture book, this story has opened with an adult man as viewpoint character, but we will soon learn to see him as a ‘father’ rather than as ‘the farmer’.

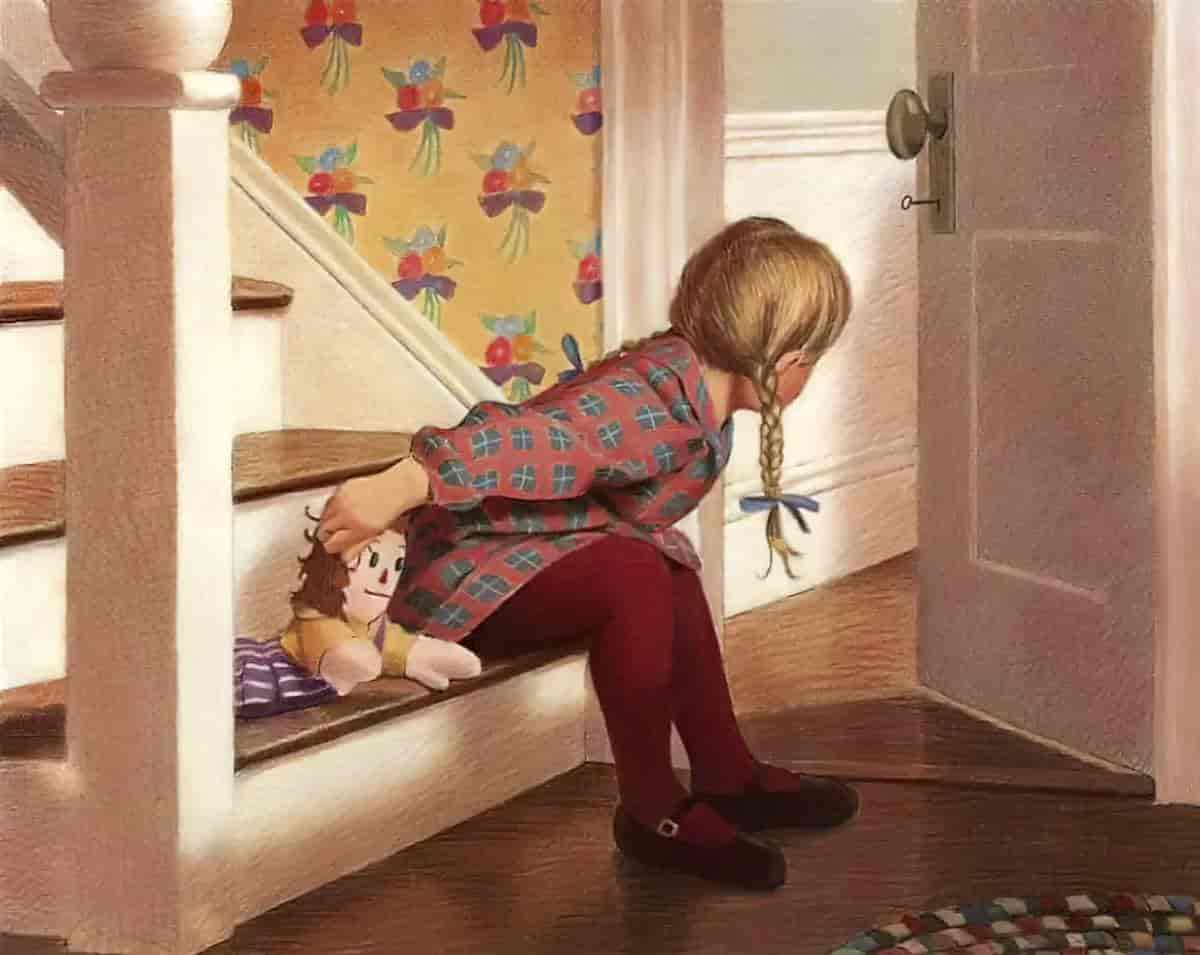

There is no clear ‘main character’ in this story as the viewpoint keeps shifting. Below is the image which switches from the father/farmer to the child. (Van Allsburg is a cinematic illustrator. Later, the camera will focus on the stranger, but from the girl’s point of view.)

Whenever we meet a character looking through a frame (in this case a door) we know they are at a disadvantage due to being on the outside. Children are inherent outsiders because their parents protect them from information, and even when handed information, children can never understand the full picture because they have not yet developed the schemas. Children listen in, eavesdrop, watch. That’s how we all learn to understand the world. This is a child’s superpower as well as their weakness. (For a great podcast on how children’s and adult brains are different, listen to Ezra Klein’s conversation with Alison Gopnik.)

Looking over her shoulder, following her (unseen) gaze, the reader is now in the girl’s position, looking through a doorway, not knowing what’s going on.

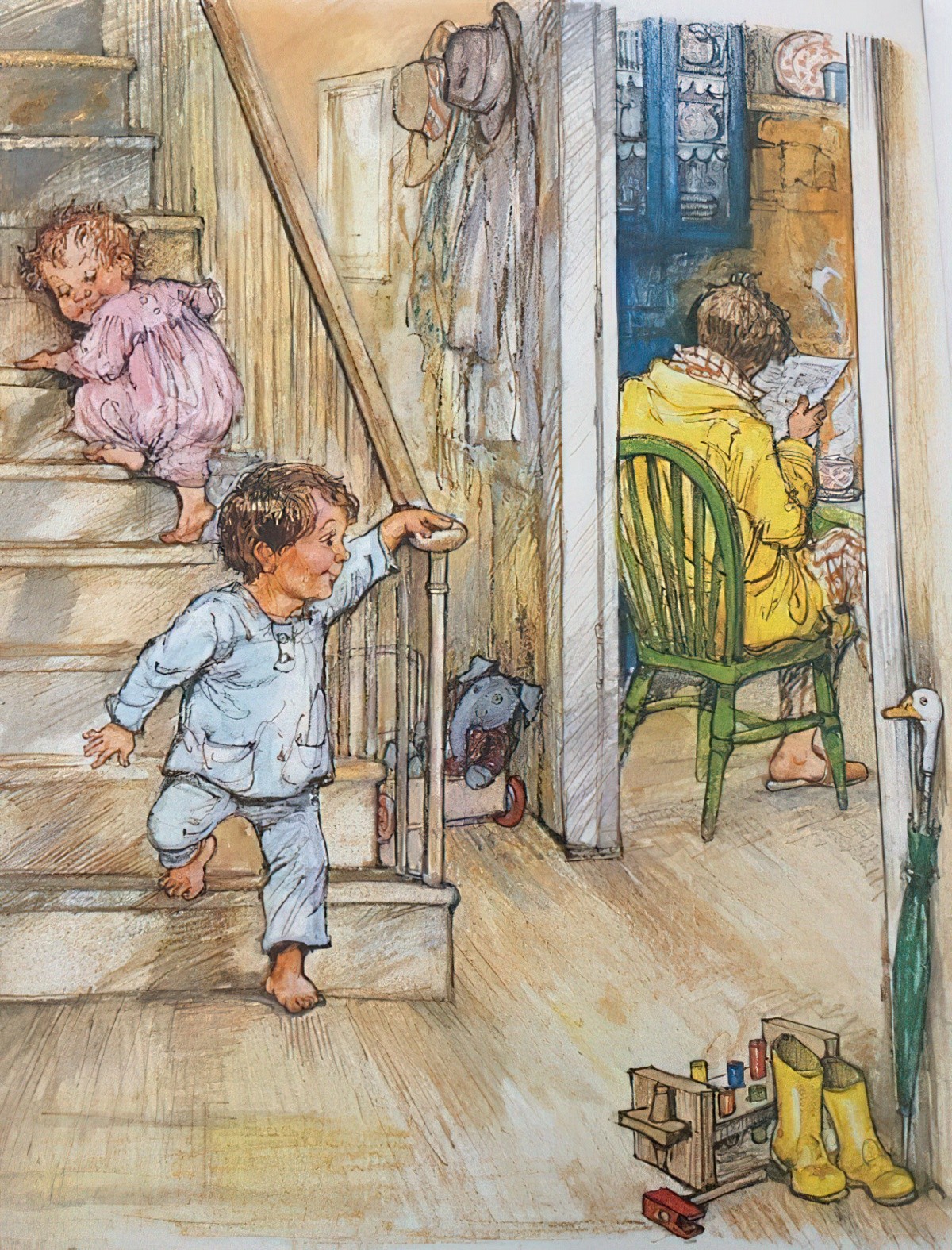

Hallways are commonly used in Western stories as an eavesdropping venue. Generally, these stories are set in your archetypal two-storied dream house and the character sits on the stairs. (Dream houses have two storeys.)

The key left in the door underscores that this child has a mystery to solve. She will solve it by watching closely, as will the reader. (However, there is some extratextual information the young reader may be missing. The young reader may not have heard of Jack Frost, or of similar demigods of nature.)

By the way, the mother of this story is backgrounded as the nurturing 1950s motherly ideal who makes the stranger comfortable and dishes him soup etc.

DESIRE

The father wants to make amends for the highway incident.

The girl wants to find out what’s going on in her house. Who is this guy?

OPPONENT

This story features a mystery rather than an opponent. (Either will work in service of a satisfying story.) But like the little girl, the reader is wondering if this stranger in the home will turn out to be malicious. In story, whenever strangers come into the home, this creates anxiety. These stories take a number of common forms. Another popular ‘stranger plot’ involves a woman who has been brought in to look after the children. Sometimes you get a plot like Mary Poppins. Other times you get The Hand That Rocks The Cradle (1992).

It wasn’t a deer the farmer found lying on the road.

The Stranger

By telling us on the first page what the man ‘is not’, Van Allsburg has also implanted in our minds the idea that this guy is somehow connected to nature. The farmer thought he was a deer at first, which suggests he may be a shapeshifter.

The steam of the soup fascinates him. Why? I’m reminded of mist which hangs over landscapes in winter.

PLAN

What can a young child really do when it comes to solving mysteries? Well, children are very good at observing. So the child does that. The reader is now viewing the strange man from child height. She (and we) watch on as the strange man gradually recovers his memory.

She watches how he blows on his soup, how he has a Pan-like affinity for wild animals (and can even coax a rabbit into his grip), and how he helps with the pitchfork, without tiring, without sweating. He is clearly super-human.

The image of the haybales is creepy — there is a long history of horror stories around haybales. From a distance (or at twilight) they tend to look like a band of marauding invaders.

Finally, the stranger cannot take his eye off the birds flying south for winter. This is a big clue. Katie is watching him watching the birds. We’re watching all of them from a low angle perspective, as if we are a creature who has ventured near, like the cat.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Stories with no ‘fight scene’ are more likely to feature a femme character, in this case a little girl. In order to get through these stories, the character in a so-called Female Myth will vuse their brains rather than brawn. In this case, the girl (and reader) use powers of observation.

Because these stories don’t feature a big battle scene, they do require something else to achieve story-worthy tension. In this case, the story opened with a mini battle scene: the near-death experience of a man who is hit by a car. This incident serves to set the emotional tone.

The struggle here is an emotional one: Katie’s family love having the stranger around. He is a big help on the farm and a fun guy to hang out with. But he cannot stick around forever. That would go against the order of nature. As evidence, the pumpkins are growing larger than ever. From tales of excess such as The Magic Porridge Pot we know there is a great danger in excess, no matter how much we fantasise about it. We fantasise about ikeeping a loved one forever, as people during famine fantasised about a never-ending supply of porridge. Even when things are terribly difficult, we somehow realise that to have it any other way would be to upset equilibrium.

The stranger must move on. So one day he does. No warning. This is basically a story about death and loss, with the comfort that everything has its time, and soon that time will be over. We then become what we were before: at one with the larger thing we call ‘nature’.

The Baileys hurried outside to say good-bye, but the stranger had disappeared’.

The Stranger

Isn’t that always how death feels? Even if we had a chance to hug a loved one goodbye, their departure always feels premature and abrupt.

ANAGNORISIS

So why does the stranger look so much like the girl’s father? I believe this is preparing Katie for his death. There’s no indication that he will die anytime soon, but around Katie’s age we learn that everybody dies, and that our parents will die before we do. This is a disturbing thought. The idea of dying before our own parents is another disturbing thought, because it means something terrible has happened to us prematurely. There is no easy way to sit with this knowledge. Later, in our teens and early twenties we really understand what it means to die. As children we knew intellectually that we would die someday, but we didn’t really feel it. We only later understand what Martin Heidegger called Being-toward-death.)

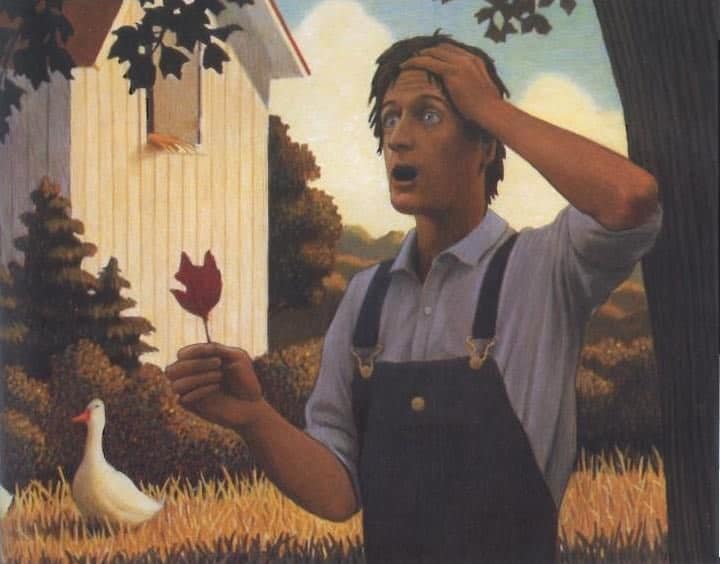

In the image below, we watch the stranger have a realisation. He has worked out who he is, and what he’s meant to be doing. Has the reader? Probably not yet. But the look on his face makes us wonder what he has realised. He is holding the red leaf as a clue. He is meant to be changing the colour of the leaves in time for winter!

How does Chris Van Allsburg help the reader to realise what the stranger has?

After the visitor has departed, we see a birds’-eye-view of the father, mother and girl as they stand on their front lawn, wondering where he has gone. The stranger has flown upwards, into the sky and therefore into some supernatural world. The reader now sees the family from his godlike perspective. As the story draws to a close, so too, do the family get smaller and further away. Yes, this guy is supernatural.

The stranger is revealed to be a Blow-in Saviour archetype a la Mary Poppins rather than the Blow-in Dastard we all feared, showing that we can in fact trust strangers sometimes.

NEW SITUATION

Van Allsburg likes to leave a touch of magic in the ‘real worlds’ where supernatural visitors have been. In this case he leaves a permanent lag in the colour of leaves, and the careful reader with prior knowledge regarding demigods of nature has deduced that the temporary bout of amnesia has caused this strange phenomenon. This situation will presumably continue forever.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Unless readers extrapolate, this story won’t make sense. It may still function as a satisfying glimpse into a weird event in a little girl’s life.

RESONANCE

Stories about strangers continue to be popular and I suspect they always will be. We have evolved to be wary of newcomers, probably because historically (and even now) other people are our greatest threat. Communities need newcomers in order to thrive, and stories like this help us to imaginatively deal with the anxiety around admitting someone different into our lives. This stranger happens to be the guy who keeps seasons ticking over; he is necessary to our very existence!

Stories which utilise the four seasons as metaphor also continue to be popular, though there are many parts of the world where four seasons have been pasted over top of an ancient (and therefore more accurate) indigenous concept of weather and climate. Australia is an excellent example of a country which does not fit the four seasons model. Yet much of Australia utilises the four seasons concept anyhow. We would all be better served decolonising weather concepts.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

People have personified the seasons for a long time, and imagined a ‘passing of the baton’. Perhaps the two women in the image below are the same person. Spring is often coded as youth, and winter as old age. In this way, seasons map onto the human life cycle.

If you enjoyed the artwork in “The Stranger”, check out the British painter Simon Palmer.

You may also like the work of Grant Wood.