With similarities to Million Dollar Baby, The Homesman is a film about an old man who has regrets but no character arc after meeting a young woman in desperate circumstances. The 2014 Homesman film is closely based on the novel by Glendon Swarthout, first published 1988. Glendon Swarthout died just four years after this novel was published.

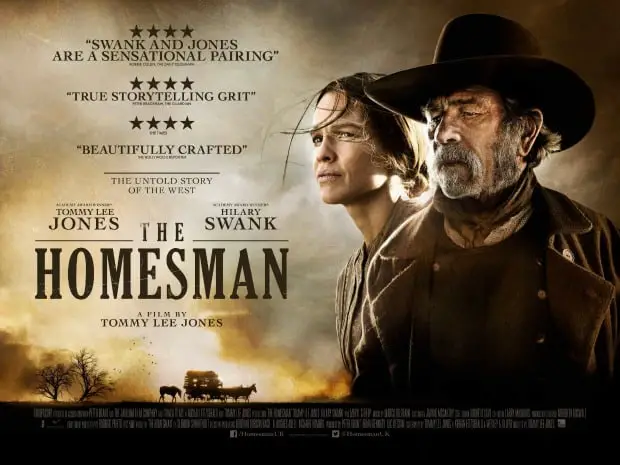

Hilary Swank has a tendency to wind up ‘starring’ in films which are ostensibly about her — the film might even be named after her character — but in which she exists to assist the character arc of the old man who she chooses (sort of) to come into her life due to desperate circumstances. In Million Dollar Baby it was Clint Eastwood (director); in this film it’s Tommy Lee Jones (also director). So if you’re wondering why Tommy Lee Jones stands front and centre in the movie poster looking contrite while Hilary Swank is literally on her knees looking desperate, we can at least say that it’s an honest representation of the character arc within, even though what we see at the beginning indicates these two should switch positions.

I do wonder if these old men of Hollywood even realise that they haven’t made a film about a woman — that it’s still all about them.

PREMISE OF THE HOMESMAN

The premise of a story is a combination of character and plot. (It has to have a double track line in order to work.)

The premise as written on IMDb doesn’t seem self-aware that the film is really about Tommy Lee Jones; it is written as if Mary Bee Cuddy is the main character:

Three women who have been driven mad by pioneer life are to be transported across the country by covered wagon by the pious, independent-minded Mary Bee Cuddy, who in turn employs low-life drifter George Briggs to assist her.

It would be more accurate to rewrite the premise with George Briggs as the main character:

Wild West Wanderer George Briggs is saved from hanging by independent-minded Mary Bee Cuddy, who then employs him to assist in the cross-country transportation of three women who have been driven mad by pioneer life.

I’m thinking the writers didn’t use that particular premise to create the story — what we see on IMDb is often more of a synopsis than a premise. The premise not only needs the double track line of character and plot — it also needs to show some sense of an outcome. How do the characters change?

Wild West Wanderer George Briggs is saved from hanging, and also from his meaningless, bludging existence, by independent-minded Mary Bee Cuddy, who employs him to assist in the cross-country transportation of three women who have been driven made by pioneer life.

Mary Bee Cuddy is a prime example of The Female Maturity Principle in storytelling. Mary Bee starts out strong and determined. She leaves us strong and determined. The other women in the story — the minister’s wife, the daughter who runs the inn, are Mary Bee Cuddy types. Women are divided cleanly in two: mentally ill and totally incapable, or godly and good.

GENRE BLEND OF THE HOMESMAN

(Period) drama, Western

When the camera lingers on a landscape or on a character’s face we know the film is asking the setting and the actors to pull the heavy weight of what would have been, in the novel, interior monologue with a bit of backstory. Sure enough, the novel offers a bit more insight into what the characters are thinking, though it’s written fairly cinematically as far as novels go. I can see how it was ripe for film adaptation.

Although the word ‘Western’ is still used, the nature of Westerns has changed so much that any ‘Western’ story since the 1960s is technically an ‘anti-Western’. The anti-Western trend started before World War II, in fact.

What’s the difference between a Western and an Anti-Western? Essentially, true Westerns were about world building — destroy and conquer, open up, tame the landscape, shoot the baddies. Anti-Westerns have a more cynical but realistic ideology. Anti-Westerns are about highly-flawed individuals trying to eke out an existence in the face of a powerful and unrelenting landscape. No one emerges unscathed. The Homesman is an anti-Western.

Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove was published a few years before The Homesman. Interestingly, Larry McMurtry had every intention of writing an anti-Western and if you’ve read the full series you’ll know there’s nothing romantic about it whatsoever. But he was surprised to see it embraced by readers and critics alike as a great love letter to the West.

The Homesman has much less humour in it — despite some light moments from Tommy Lee Jones — and is such a harsh story it would be hard for audiences to mistake this anti-Western for a love-letter to the Old West.

In both The Homesman and in Lonesome Dove, we have two characters who set off on a journey together who are such different characters they are each other’s greatest human opponent. (Let’s not count the landscape, or the out-and-out villains.) You could say these are de facto marriages, but there are also similarities to the Buddy genre.

I think of The Homesman as a Road Movie with a Western setting. The Homesman has more in common with Little Miss Sunshine (2006) than with The Great Train Robbery (1903). That said, the themes of this story are definitely Western — the contrast between freedom vs civilisation, the individual against society.

STORYWORLD OF THE HOMESMAN

Following in the footsteps of classics such as East of Eden, the camera opens by lingering on a landscape upon which nothing is happening. This is to give the audience some sense of what it’s like to live here. Days are slow and long. Few things of consequence happen — though when they do, these things are life-changing for the characters. It’s exactly how my father-in-law describes his time in the Vietnam War — 90% boredom, 10% terror.

Glendon Swarthout was born 1918, so as a kid — if he had elderly people in his life — he would’ve been in contact with people who remembered the 1850s. My favourite Western writer, Larry McMurtry, has the same advantage.

Swarthout lived through the Great Depression of the 1930s, and this no doubt influenced his characterisation — he would’ve known women like Hilary Swank — pious and good, knowing how to make the best of tough situations. It’s interesting that Mary Bee doesn’t have to worry about money — it’s only everything else she has to worry about.

The setting of the West inevitably links to the character shortcoming, which is how the best stories work. Set in the 1850s, farm life was nigh on impossible without a family to help run a plot. We are shown Mary Bee struggling to til a field with two mules. She has just enough strength as a young woman to about manage farm life because she’s at the peak of her strength, but as she gets older she’ll lose a lot of that strength. In this era and in this setting, finding a husband is a matter of life and death.

Though she loves music and used to play the piano for several hours daily, Mary Bee has no piano in the Wild West, so practises on an embroidered mat of black and white keys. This mat symbolises the sacrifice of pioneers in general.

Mary Bee inspects the ‘jail’ wagon which is to transport the three mentally ill women East. In fact, each of these characters is living in a world of slavery and each craves freedom. In the novel, much is made of the fact that this is not a typical looking wagon. To everyone they encounter along their journey, it looks like a jail on wheels.

Because this is a story about white characters in the 1850s, the small, local church plays a large role in their lives. The camera angle here shows us how the preacher occupies an elevated position, as leader of the community and decider of what’s right.

You may have noticed in children’s picture books that when the characters turn backwards, facing towards the beginning of the story, something has happened to prevent them achieving their goal. This creates a subconscious mind block for the reader. A Western in which characters travel from West to East feels backwards. It is the opposite of progress, same as a picture book with a backwards looking character.

By the time the journey East begins autumn has become winter. This makes the journey even more perilous. (I’m guessing they travel in winter in order to cross frozen rivers, as was the case in Little House On The Prairie.) Near the end, on his own, George Briggs must ford a dangerous river. See also: The Symbolism of Rivers.

Another thing to know about the milieu — cattle hustlers and cowboys like George looked down on farmers back then. (I saw this spelled out in the Lonesome Dove series.) When Mary Bee offers George marriage, trying to persuade him by telling her all about the spoils of her farm, George isn’t going to be impressed with her plans to plant pumpkins.

In this world (as in ours) there is a stark divide between the haves and the have-nots. The have-nots really do have nothing. The rich are super wealthy, having found opportunities in road-building, shipping and so on. So the sky-blue hotel for rich people which George stumbles upon seems to tower up into the sky, becoming part of it, much like a symbol of heaven.

Trees are symbolic of life. Mary Bee tells one of the women at some point that she really misses trees — there are none on the plains but out East, towns are full of them. When the audience sees a beautiful wooded landscape we know George has arrived at his destination. This is the 1850 equivalent of a suburban utopia.

Trees equal life.

The symbolism of the river is significant in any Western, too.

For white folks, at least. Notice the director decided to include a cart full of black slaves during a pan of the suburban, riverside market.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE HOMESMAN

In order to understand the story structure and fill out the ‘anagnorisis’ part, we have to treat this story as if George Briggs is the main character, not Mary Bee Cuddy.

The UK poster is the most accurate in this regard:

SHORTCOMING IN THE HOMESMAN

‘George Briggs’ (we know this isn’t his real name) has no home and family so in order to survive he has taken residence in someone else’s cob cottage while the original owner travels East to find himself a bride. He is forced to leave by Bob Giffen’s friends and neighbours, who leave him strung up, ready to be hanged by his horse.

“I deserted from the Dragoons! I ain’t attached to nothing! Just me!”

His ghost is revealed eventually as he opens up, in a rare moment, to Mary Bee. He is a deserter. He cannot stick around in any one place because if they find him they’ll surely kill him. He has also been settled down with a woman before. We don’t know the details of this failed relationship but we learn he simply up and left her when he got sick of that life. We are therefore shown that he is fully capable of doing that same thing again. He is a deserter, or a rolling stone to be generous. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ik_ciMowBq0

DESIRE IN THE HOMESMAN

This is a man who wants to be left alone to eat other people’s sheep and drink gin. He doesn’t want to do the work of survival.

In a story where the main character wants nothing more than to be left alone, other characters around him will be given the strong desires. Mary Bee’s strong desire is to do good by delivering mentally ill women back to their homes back East. Briggs gets caught up in it.

OPPONENT IN THE HOMESMAN

George’s first opponents smoke him out of Bob Giffen’s house, but that’s an ‘oppositional McGuffin’. After a comical second meeting he won’t have to worry about those guys again. It does also tell us about George’s modus operandi.

His enduring opponent is Mary Bee Cuddy, who requires him to undertake an unpleasant journey he’d rather not.

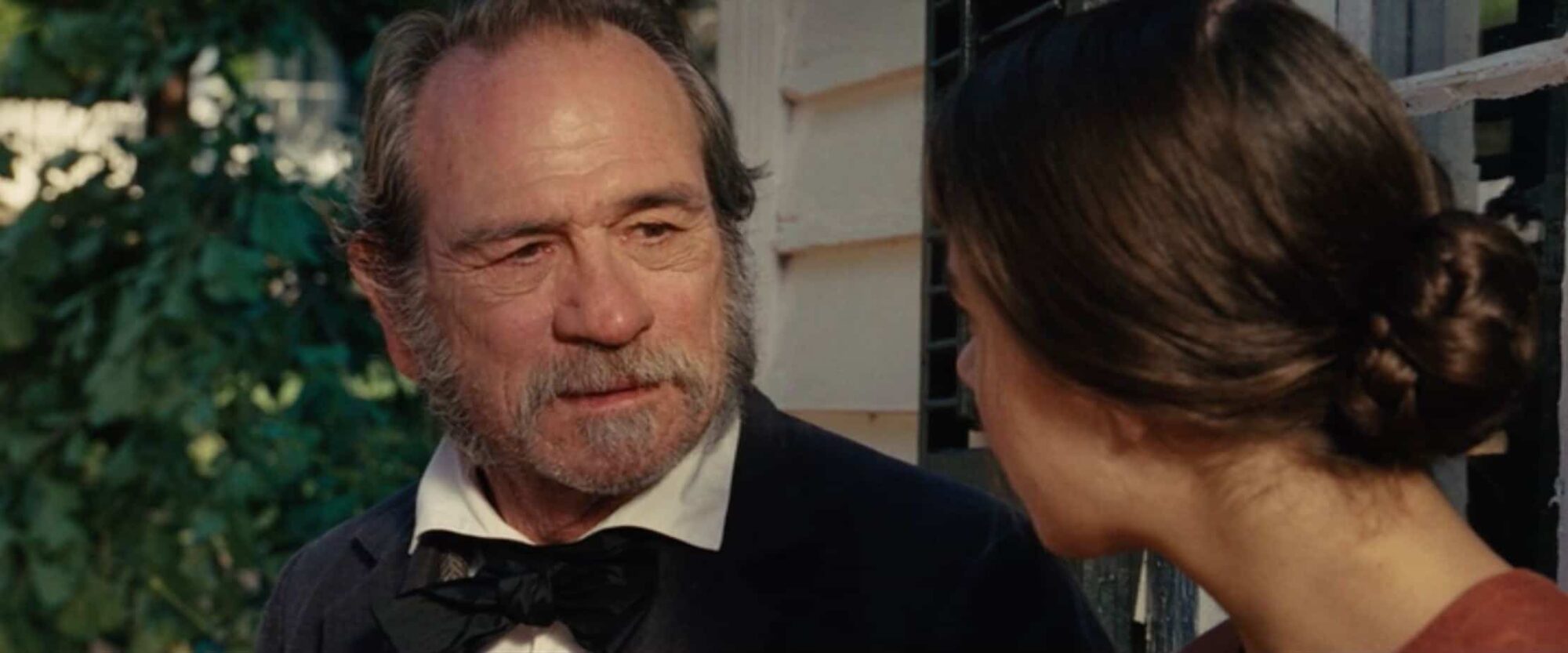

There are of course times when George and Mary Bee are companions. Here in the cave, George manologues about his time on the plains, then follows with a drunken dance, which all the women are obliged to sit and watch. Caves are of course womblike, and a good setting for sharing personal information.

PLAN IN THE HOMESMAN

George won’t be bossed around by a woman even if she did save his life, so he’ll help her just enough to assuage his own conscience. He’ll bolt at the first opportunity. He even tells her as much. The audience doesn’t have to guess at his plan.

Later in the film Mary Bee even says to George, “You’re not much of a one for making plans.” It is Mary Bee driving the larger plan, but if you look closely at the scene level you’ll see that in fact George does make plans. He makes them on the spur of the moment rather than planning ahead. He is a world-weary cowboy hustler, and he has learnt that there’s no point in planning ahead. Far more successful to live on your wits.

So when the Indians turn up he has a plan ready. He knows there’s a chance they’ll kill him, so he’ll offer them one of the horses and hope that does them. His plan works.

BIG STRUGGLE IN THE HOMESMAN

This story follows mythic structure. A character leaves home (however temporary in George’s case), embarks upon a lengthy journey, fights various characters and in the end returns ‘home’ (which may or may not be his actual home). (Mythic journeys almost always feature male characters.) He’s a changed man, but has he had a character arc that’ll help him lead a better life? Well, no. In this regard, The Homesman is very much like The Wrestler, Hud and Lonesome Dove. These men fail to learn from their lived experiences and that is their tragedy.

In a mythic journey the main character will face a number of big struggles. In this story we have:

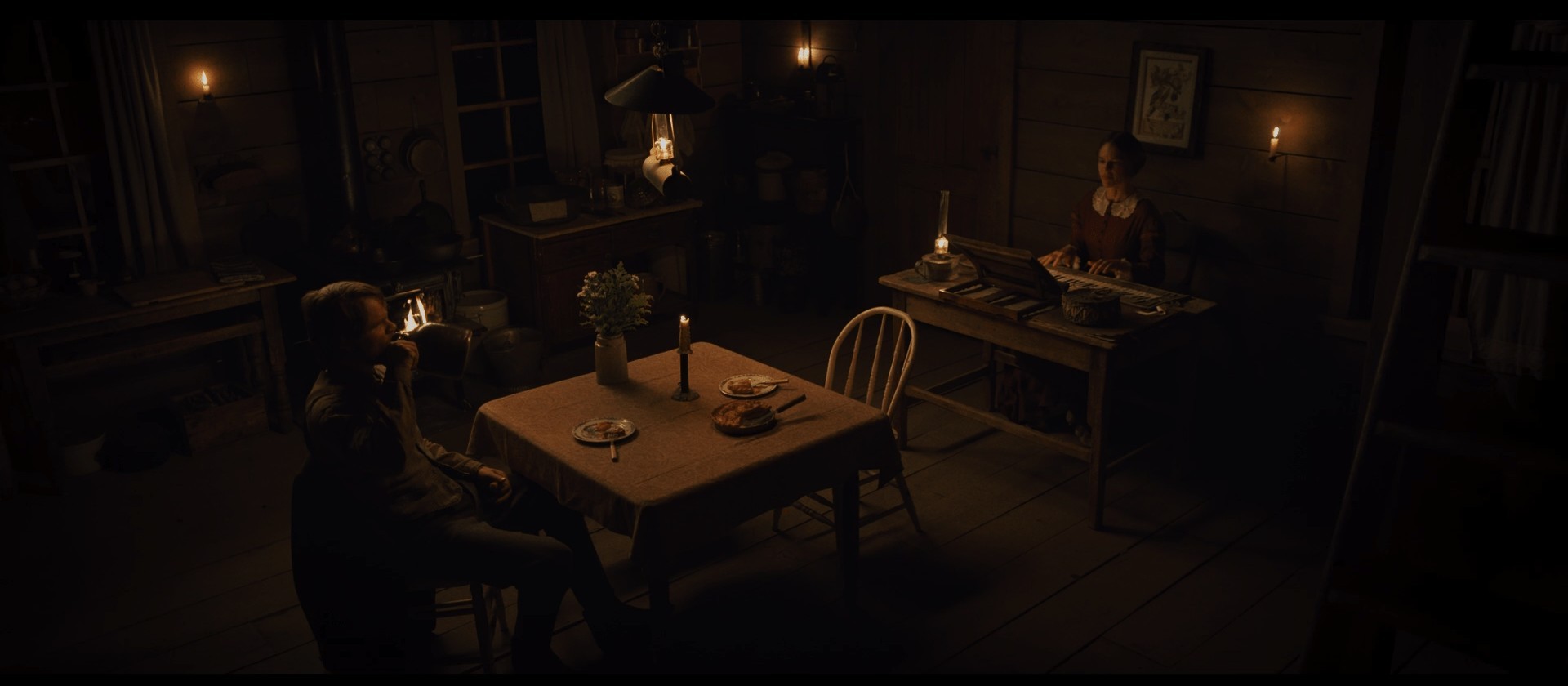

- The argument in Mary Bee’s house after she puts him to work and then makes him sleep in the stable for cursing god at her dinner table and refusing to hold up his end of the bargain. (We don’t know where he actually sleeps but Mary Bee gets the last word.)

- The gun big struggle in which he accidentally comes face to face with one of the men who meant to hang him. (With Mary Bee’s help he gets away.)

- The argument about whether he’s allowed a bottle of gin or not. (He wins that one.)

- The weather — it is very cold and snows.

- The women themselves, who fight among themselves if not tied up.

- The Pawnee Indians who might kill them.

- The actual fisticuffs with the horrible man who has claimed the woman who ran off.

- The argument that ensues after Mary Bee accuses George of not lighting a fire when she fails to catch them up after stopping to repair a child’s grave

- At the fancy hotel George is given opportunity to utilise his trickster side as he sets fire to the joint and takes the feast set up for posh people. This big struggle is a good example of putting the rich and the poor directly up against each other, which always leads to good drama in fiction. We root for the poor man. He is punishing one of the 7 Deadly Sins, greed.

While George almost loses his life being strangled by the kidnapper, Mary Bee takes a moment to contemplate death, and how close they all are to it, when she picks up the bone of the 11-year-old girl whose grave his first been robbed, her body mauled by wolves.

This foreshadows Mary Bee’s literal brush with death when out of sheer stubbornness (and sense of right) she separates herself from the wagon.

ANAGNORISIS IN THE HOMESMAN

George starts out not only lonely, but alone by choice. He doesn’t need people. He accompanies these women reluctantly.

We see the first inkling of another side of his established character when he hands Mary Bee the gun and instructs her to save herself if the negotiations with the Indians go wrong. We see it again when he saves the woman from the man who wants to keep her as his mute sex slave.

When the camera lingers on George looking on as Mary Bee sets about her tasks, or when she plays the piano mat by the river, we see him having a bit of a anagnorisis. But he has no such thing. He is learning a little about Mary Bee in this moment, and nothing about himself.

So, Mary Bee hangs herself. When even George won’t have her she feels she might as well be dead and done with it. The novel tells us that the guilt at having sex outside marriage, and the feeling that the women and God is watching, is what drive her to it.

This is looking more and more like the Million Dollar Baby arc, right? A woman must die in order to give opportunity to a male character to undergo a character arc. There is a long, problematic history with this trope, precisely because it is used so often. So frequently in story, a woman has sex and then has to die for it. This is a criticism of Thelma & Louise, which I also love as a stand-alone story.

Now we know that George has a moral decision to make, and because we’ve seen what he is capable of, we wait and watch as he deserts these helpless women once again.

First he directs his anger at the women, lecturing them on how crazy they are as he digs Mary Bee’s grave. This indicates that he will be going through the seven stages of grief.

“I’m going home by myself. You’re on your own. Somebody’ll come along and tend to you. Not a damn one of you can understand a word I’m saying.”

He trots off on his horse leaving the mentally ill passengers to fend for themselves. He crosses a river and realises he’s being followed by puppies who have bonded with him. He is forced to save them as they almost drown. Now that he’s saved them he realises he does care for them a bit after all. The Ben Franklin Effect is quite often used in stories to precipitate a character arc. Now he must tend to them himself rather than just looking on as Mary Bee did it.

George’s character arc is underscored when he pulls up at the fancy hotel and deals with a snobby, uncaring man who refuses service because he doesn’t like the cut of his gib. Now George Briggs starts to look like a decent character.

When George feeds the women he is shown to have taken over the nurturing role.

The reverend’s wife: “She must have been a truly fine human being.”

George: “She truly was.”

NEW SITUATION IN THE HOMESMAN

The women are in the safe hands of the reverend’s wife.

George to the maid at the hotel: “Mary Bee Cuddy was as fine a woman as there ever was.”

George’s regret is apparent to the audience when he asks the 16 year old who looks like Mary Bee to marry him. She looks like Mary Bee.

We’ve had this foreshadowed before, when she was framed by the bathroom mirror. (This is also the reason he notices she’s not wearing shoes — she creeps in on him in the bathroom and he felt exposed.)

But he is still alone in the world. The scene with him at the gamblers’ table, in which it is revealed that the Bank of Loup has gone bust and he has not a penny to his name, shows him ostracised, as only players are allowed to play at the table.

This isn’t just the table rejecting him. This is civilised society rejecting him.

The next morning we see him sitting alone outside the hotel.

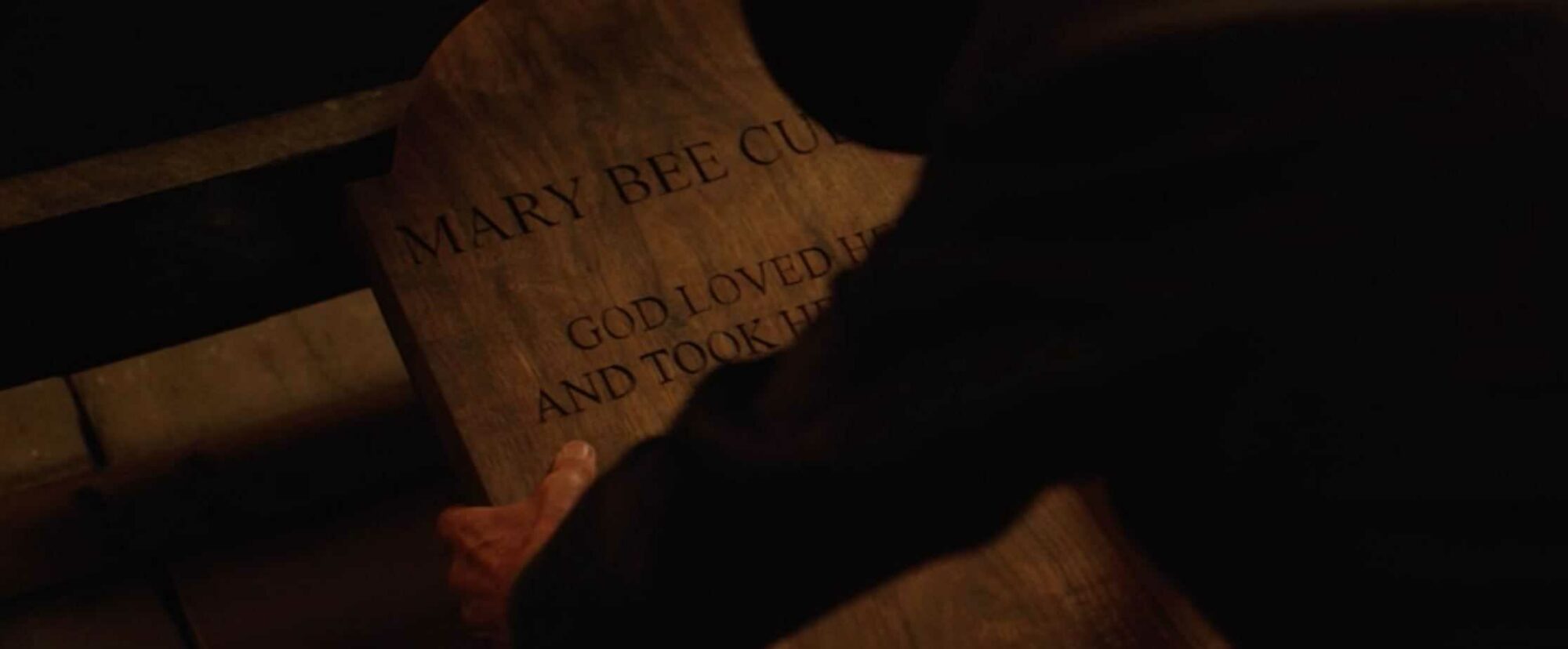

He buys a gravestone for Mary Bee and holds an impromptu, drunken wake for him on the barge. Along with the shoes for the girl, this is a Save the Cat moment which helps the audience to feel more kindly towards him. Save the Cat moments are generally utilised at the beginning of a story because the writer needs the audience to empathise with the character and care what becomes of them, but here it is used at the bum end of the story, with the message that George’s gestures are too little, too late.

George says he’s going to return West. We know this anyway — there’s no way a ruffian like George would be accepted in Fairfield. There is some suggestion, however, that he will at least try to fit in here.

Also, he needs to go somewhere with no trees. Trees equal death if they also equal life. He’s going back West to die.

We extrapolate that George will continue as before, getting drunk and essentially alone. The camera zooms out and we are left with a tiny image of George dancing in front of the flame.

But we also know that George has one more person’s memory to bury in his memory — that of Mary Bee Cuddy, who had to kill herself before he took her seriously.

Like Randy the Ram in The Wrestler, George goes to a dangerous place after losing the women in his life and everything important to him. The great tragedy of this film is that George comes so close to turning himself into what passes for a good person. If only, we think. If only the Bank of Loup hadn’t gone bust.

When a heavily flawed main character comes very close to leading a good life the audience really feels the tragedy.